To the editor

Since 2000, several small randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that ketamine has potent and rapid-acting antidepressant effects in patients with treatment-resistant depression (1). Despite a lack of long-term data or FDA indication, many community providers and academic centers have begun offering ketamine treatment to patients with MDD and other psychiatric disorders, determining the existing evidence justifies use for some individuals. The practice patterns of such providers have not been studied.

Methods

From September 2016 through January 2017, a web-based survey was sent to physicians nationwide inquiring about their clinical practices using ketamine for psychiatric disorders. Physicians were identified through a systematic web search for sites advertising ketamine treatments for depression and through our relationships with academic and community colleagues. The study was considered exempt from full IRB review.

Results

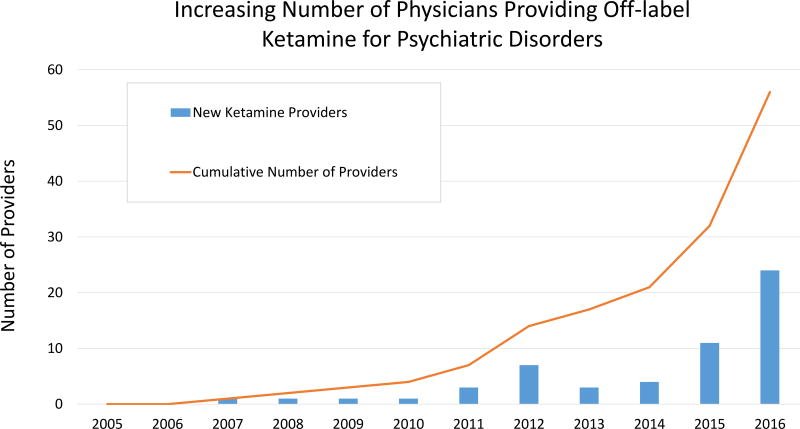

We identified 85 providers through our search. Survey requests were sent to 76 providers (email addresses could not be acquired for 9) and responses were received from 57 (75.0%). Most (73.7%) survey respondents worked in private practice, with a minority in academic settings (14.0%) or Health Maintenance Organizations (8.8%), with a regional distribution as follows: West Coast (31.6%), Northeast (19.3%), Southeast (15.8%), Mountain West (10.5%), Mid-Atlantic (10.5%), and Midwest (8.8%). Most (66.7%) providers were trained in psychiatry, with others trained in anesthesiology (22.8%), emergency medicine (3.5%), or family medicine (3.5%). Most providers (73.7%) administered ketamine in an office-based setting, with a minority (21.1%) administering ketamine in a hospital-based setting or surgical/procedural suite. The majority of practitioners reported starting to provide ketamine for psychiatric disorders relatively recently, with a notable increase in cumulative number of providers since 2012 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Total number of physicians initiating the practice of providing ketamine off-label for the treatment of psychiatric disorder per calendar year (bars) and cumulative number of ketamine providers over time (line).

The most commonly reported diagnosis treated was Major Depressive Disorder (72.2%), followed by Bipolar Disorder (15.1%), and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (5.7%). Most providers (87.7%) reported administering ketamine via an intravenous route, with a minority reporting using an oral (22.8%) or an intranasal (19.3%) formulation. Among providers reporting intravenous administration, 44.0% reported using a dose of 0.5mg/kg infused over 40–45 min, the typical dose in most research protocols (2); a minority reported using a range of doses between 0.5–1.0mg/kg (12.0%) or between 0.5–3.0mg/kg (14.0%).

Approximately half of providers reported monitoring heart rate (48.1%) and pulse oximetry (54.0%) at least every 5 minutes during the infusion, with 25.9% monitoring blood pressure at least every 5 minutes. Most providers reported monitoring heart rate (77.8%), pulse oximetry (80.0%), and blood pressure (75.9%) at least every 15 minutes during the infusion. Few providers reported no monitoring of heart rate (1.9%), pulse oximetry (10.0%), and blood pressure (1.9%).

Most providers (89.5%) reported offering ketamine on a continuation/maintenance basis (defined as a time period greater than 1 month). Providers reported the average frequency of maintenance treatments as monthly (29.8%), once per 3 weeks (21.1%), once per 2 weeks (12.3%), or less than monthly (15.8%). Providers reported that 64% of patients payed for ketamine out of pocket, with 23% of patients having a portion of the cost reimbursed by insurance, and 13% of patients had other payment structures.

Discussion

This is the first attempt to characterize practice patterns among physicians providing ketamine as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. While there are limitations to this approach, including the inability to ensure this is a representative sample of all ketamine providers around the country, we identified a rapidly growing number of physicians of a variety of specialties and geographic locations offering ketamine treatment for psychiatric disorders. Various dosing protocols were reported, though the majority of research studies have only used one protocol (2). These results underscore the urgent need for more research on the use of ketamine in psychiatric disorders in clinical settings in order to establish evidence-based treatment regimens and the safety of long-term use. The growing use of ketamine in this population coupled with the concern for potential adverse clinical consequences of repeated dosing (abuse liability (3), cognitive impairment (4)) argue for the importance of a registry (5) to follow psychiatric patients who receive ketamine longitudinally.

Acknowledgments

STW receives research and salary support from the NIMH (T32MH062994-15) and from the Brain and Behavioral Research Foundation (formerly NARSAD) and the Robert E. Leet and Clara Guthrie Patterson Trust.

GS has received consulting fees from Allergan, Alkermes, AstraZeneca, Avanier Pharmaceuticals, BioHaven Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Hoffman La-Roche, Janssen, Merck, Naurex, Novartis, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Servier Pharmaceuticals, Taisho Pharmaceuticals, Teva, Valeant, and Vistagen therapeutics over the last 36 months. He has also received additional research contracts from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Hoffman La-Roche, Merck, Naurex, and Servier over the last 36 months. Free medication was provided to GS for an NIH-sponsored study by Sanofi-Aventis. In addition, he holds shares in BioHaven Pharmaceuticals Holding Company and is a co-inventor on a patent ‘Glutamate agents in the treatment of mental disorders’. Patent number: 8778979.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No other authors have any disclosures.

References

- 1.Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, Potash JB, Tohen M, Nemeroff CB. Ketamine and Other NMDA Antagonists: Early Clinical Trials and Possible Mechanisms in Depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:950–966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGirr A, Berlim MT, Bond DJ, Fleck MP, Yatham LN, Lam RW. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive episodes. Psychol Med. 2015;45:693–704. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sassano-Higgins S, Baron D, Juarez G, Esmaili N, Gold M. A review of ketamine abuse and diversion. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:718–727. doi: 10.1002/da.22536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan CJ, Muetzelfeldt L, Curran HV. Consequences of chronic ketamine self-administration upon neurocognitive function and psychological wellbeing: a 1-year longitudinal study. Addiction. 2010;105:121–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanacora G, Heimer H, Hartman D, Mathew SJ, Frye M, Nemeroff C, Robinson Beale R. Balancing the Promise and Risks of Ketamine Treatment for Mood Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016 doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.193. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]