Abstract

During catastrophic disasters, government leaders must decide how to efficiently and effectively allocate scarce public health and medical resources. The literature about triage decision making at the individual patient level is substantial, and the National Response Framework provides guidance about the distribution of responsibilities between federal and state governments. However, little has been written about the decision-making process of federal leaders in disaster situations when resources are not sufficient to meet the needs of several states simultaneously. We offer an ethical framework and logic model for decision making in such circumstances. We adapted medical triage and the federalism principle to the decision-making process for allocating scarce federal public health and medical resources. We believe that the logic model provides a values-based framework that can inform the gestalt during the iterative decision process used by federal leaders as they allocate scarce resources to states during catastrophic disasters.

Keywords: ethical issues, politics, state/local issues

Catastrophic disasters have become familiar experiences in our contemporary world, and they require planning by government leaders so that they can provide an efficient and effective response. These disasters range from natural ones such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and epidemics to terrorist attacks involving improvised explosive devices and nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons. Emergencies and disasters begin and end locally, and most are wholly managed and resolved at the local level. Some incidents require a unified response from local agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector. Some require additional support from neighboring jurisdictions through mutual aid agreements.1 Most disasters are likely to cross multiple political jurisdictions and geographic boundaries and require a coordinated public health and medical response.

In catastrophic events, the response becomes even more complicated, requiring decision makers across multiple levels of government to allocate available resources quickly, efficiently, effectively, and fairly to optimize and synchronize resource distribution to save lives and to mitigate suffering and morbidity. The decision-making process used by federal leaders during catastrophic events is dynamic, often based on limited situational awareness and gestalt, and can be strengthened by a structured, ethically-based process. The ethical framework offered here may provide a useful supplement to the National Response Framework’s strategic and tactical guidance for incident response.2

During the past 2 decades, an ethical basis for allocation of scarce resources during public health emergencies has been the explicit starting point for practical guidance regarding planning for and responding to public health emergencies.3–12 In general, these approaches seek to develop leadership decision-making processes that are “values based,” meaning that they are based on both substantive ethical principles and fair procedures.13

Values-based decisions require explicit attention to strongly held beliefs, ideals, principles, and standards to inform leadership decisions in relation to societal goals. It is especially important that government leaders who make decisions regarding publicly held health and medical resources establish values-based decision processes well in advance of a catastrophic disaster. Such ethical preparedness14 is important to the public trust and central to making difficult choices in real-time decision making.8,11 Ethical preparedness helps decision makers to anticipate the judgments that will have to be made and model such judgments in a way that is explicit, transparent, and widely shared.15

In a federal system of government, federal leaders are responsible for coordinating the provision of federal resources including allocating resources when needs exceed the available resources. While the National Response Framework describes the distribution of responsibilities between federal and state governments during disasters, little has been written about how decisions should be made by a federal government in disaster situations when resources are not sufficient to fully meet the needs of several states (state refers here to the 50 states, the District of Columbia, US territories, and Native American tribes, all of which may request federal assistance) simultaneously. To address this concern, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) at the US Department of Health and Human Services convened a working group in 2011 to consider the question of federal public health and medical resource allocation. The framework presented here grew from that group’s work and engagement with stakeholders in ethics, disaster preparedness, and emergency management.

In this report, we present the ethical framework developed by the working group, the processes and outcomes from the stakeholder engagements, and the resulting logic model intended to assist federal decision makers to efficiently, effectively, and fairly allocate limited federal resources to states. The framework builds on the principles that have been identified to guide allocation decisions for individual patients in scarce resource situations9,16–19 and considers how the principle of federalism can be applied to the task of allocating scarce federal public health and medical resources to states. In a catastrophic disaster, situations will arise in which specific resources are insufficient to meet demand or need. We propose this ethical framework and logic model to guide allocation decisions within this dynamic context.

METHODS

The working group comprised individuals with ethical, legal, clinical, disaster planning, and emergency management experience and expertise. Working group members as well as subject-matter expert reviewers are listed in the Appendix.

To develop the framework, the group identified underlying assumptions; enumerated substantive and procedural ethical principles to guide decision making; identified concepts consistent with the principle of federalism that make this type of decision making different from that at the individual or community level; specified criteria to apply the concepts to allocation decisions; and applied a scoring system to the criteria. After the original framework was developed it was presented in 3 separate workshops to obtain feedback on its ethical merits and the feasibility of its application. These workshops allowed participants to consider the proposed criteria and provide feedback using a scenario-based approach. Finally, the authors engaged experts with expertise in modeling scarce resource decision making to further refine the framework and approach.

Development of the Original Framework

Assumptions

The working group identified a series of assumptions that underlie the proposed framework. The assumptions include the following:

The decision process is designed to be used in any stage of a disaster response when there is scarcity of a specific resource needed by affected states. Scarcity is defined relative to a specific resource (eg, mobile medical units, ventilators, vaccine, or therapeutic treatment stocks) and a specific timeframe. It means that in spite of strategic stockpiling and regional cooperation and allocation, the demand or need for the specific resource exceeds the supply that is available or expected to become available within a specified period of time. This assumption encapsulates the critical and most fundamental dilemma that federal leaders face in making allocation decisions. Over time, additional resources may become available; however, allocation of existing resources must be initiated to respond to immediate need.

A separate allocation decision should be made for each scarce resource.

-

Decision makers must be prepared to make allocation decisions in 2 possible sets of circumstances:

When some or all affected states have made formal requests for assistance, as outlined in the National Response Framework, ie, the typical “pull” of federal resources to meet the need2; and

When catastrophic effects on states’ governance prevent it from making a formal request, but when there is an expectation of extreme need based on available information, ie, when the federal government may promote resources toward the need, pending further assessment.

Decision making during catastrophic events, especially in the early hours, will probably be based on incomplete information until situational awareness improves.

It is likely that some resources will be adequate to meet the needs and should be distributed as needed. Other resources or sets of resources will be scarce and cannot be provided to all who need them. In the latter case, other available and suitable resources can be substituted to provide “functionally equivalent” resources.20

Substantive and Procedural Values

The working group also proposed a set of fundamental ethical values to consider when making decisions about allocating scarce federal public health and medical resources. The work group based the framework on the literature on medical and public health ethics and theories of distributive justice and applied them to decisions regarding scarce resource allocation. The intent was to reflect the values of society and existing federal guidance.

Substantive values are strongly held ethical ideals that inform decisions and actions (ie, decisions and actions about what is right or should be done in the face of uncertainty or conflict).8 The substantive values the work group identified are shown in Table 1. Because consensus on substantive ethical principles is often difficult to achieve, it is generally recognized that scarce resource allocation decisions must also be based on fair procedures. Such procedures help ensure that even when agreement is not unanimous regarding the allocation decisions themselves, stakeholders will recognize that the decisions resulted from processes that are open, reasonable, inclusive, and fair. Procedural values, therefore, are ethical ideals that promote and can be used to evaluate the fairness of a process for decision making under uncertainty or conflict. Ensuring a procedurally fair process is important precisely because stakeholders may differ about substantive values. The procedural values that the work group identified are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| Fidelity to mission and protection from harm | Relevant federal agency missions include protection of human health, prevention of death, injury, disease, and harmful disruption to the public in times of disaster. |

| Federal public health and medical response uses resources under its control to prevent death, injury, disease, and harmful disruption to the public. Federal agencies evaluate how to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number (utility) among other morally relevant considerations, including priority to those who are least able to help themselves (prioritarianism). | |

| Fairness | All states have a claim to receive a fair portion of the federal resources they need. The ethical reasoning behind need-based considerations in situations of scarcity is that every state is subject to misfortune, and fair treatment ensures that no state is penalized for its misfortune. During a disaster, when federal resources are insufficient to meet the needs of all affected states, federal agencies makes equitable decisions about the proper allocation of available resources, that is, decisions based on fair processes and criteria. |

| Allocation will not be made using criteria that are unfair or illegal (eg, allocating resources to benefit politically friendly states (cronyism, favoritism) or to benefit family members of decision makers (nepotism). | |

| Trust | Trust is an essential component of well-functioning relationships among federal agencies, states, and the public. Federal agencies maintain and enhance stakeholder trust by developing ethical frameworks and implementing criteria for allocation of scarce federal resources in a disaster. As public servants, federal agency leaders are responsible for maintaining the public trust, placing duty above self-interest, and managing resources responsibly. |

| Subsidiarity | A central authority should have a subsidiary function, performing only those tasks that cannot be performed effectively at a more immediate or local level. In a disaster, federal agencies take only those actions that are necessary to achieve its mission of protecting the health of all Americans. The measures taken by federal agencies to protect the public from harm should not exceed what is needed to address the actual risk to, or critical needs of, the community. |

| Solidarity | Responding to a disaster requires solidarity and cooperation within/among federal agencies, states, tribes, and communities. Federal agencies foster mutual support and common interest. Agencies should act in a collaborative, trust-based manner that minimizes inclination to pure self-interest among stakeholders. |

| Stewardship | In a disaster, federal agencies are guided by their commitment to responsible management of federal resources to achieve the best public health outcomes given the unique circumstances of the disaster, scope of need, and availability of resources. |

| Preparedness: Advance planning and goal setting | To fulfill their missions, federal agencies develop and clearly communicate federal asset allocation processes and criteria in advance of a disaster. Anticipating, planning, and communicating strategies for effectively allocating federal resources in disaster situations will promote trust, solidarity, fairness, and transparency in decision making. |

| Evidence-driven orientation | To achieve the best possible public health outcomes, federal agencies use scientifically sound practices and continually assess the impact of allocation decisions to assure their ongoing value. |

TABLE 2.

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| Reasonableness and relevancy | Federal agencies base their allocation processes and criteria on reasons (ie, evidence, principles, and values) stakeholders can agree are applicable to meeting state and local needs in a disaster. The substantive values outlined here guide decisions. Plans or playbooks are developed in advance to inform decisions. |

| Transparency and public accessibility | Federal agency decision-making processes and criteria for allocation of federal public health and medical resources are transparent and publicly accessible. Transparency means that agency leaders clearly explain how decisions were made, who was involved, and the reasoning behind the decisions. Publicly accessible means that in addition to publicly posting information related to allocation of federal resources, leaders will also take action to promote the message to all segments of the public and/or relevant state authorities.21,22 |

| Inclusiveness | Federal agencies ensure that their allocation processes and criteria are developed explicitly with stakeholder views in mind, and with opportunities to engage stakeholders in the decision-making process, to the extent feasible. |

| Preevent: Federal agencies engage with stakeholders to inform the criteria that will be used. | |

| During event: To the extent feasible, decision-making bodies will quickly confer with subject matter experts who understand the medical consequences of the specific incident, persons who have expertise in allocation of scarce resources, and political leadership at all levels to inform decisions. | |

| Responsiveness and accountability | Federal agencies establish mechanisms to revisit and revise decisions as new information emerges throughout a disaster. Such decisions include establishing mechanisms for real-time evaluation as situational awareness improves and the impact of decisions is known. This approach provides a quality improvement mechanism for difficult and controversial decision making, and demonstrates responsiveness on the part of leaders. |

| Federal agencies carry out an evaluation and revision of procedures after disaster responses are completed. |

Concepts Consistent With the Principle of Federalism

Along with these substantive and procedural values, guidelines for fair allocation of federal resources should take into account political theories about federalism—the division of sovereign authority among levels of government.21 As described in Table 3, federal leaders should apportion resources to disaster-affected states in a manner that takes into account features of a well-functioning federal system.22

TABLE 3.

| Concept | Example |

|---|---|

| Accordance with commonly used formulas for providing state aid | CDC’s public health emergency preparedness25 and ASPR’s hospital preparedness program26 cooperative agreement funds are awarded in accordance with a statutory population-based formula in section 319C-1(i) of the Public Health Service Act |

| Promotion of cooperation among states | Emergency management assistance compact1 |

| Avoidance of unintended consequences | Ensure that population-based resource allocation does not exacerbate the condition of the worst-off state, or the condition of those who are worst off within a state |

| Facilitation of collaboration between federal and state efforts | National Response Framework2 guides this interaction |

| Effective coordination with other federal agencies | Engaging with other federal agencies that have public health and medical assets so their available assets are factored into the allocation decisions to promote a synergistic impact |

| Promotion of capacities of local communities | Providing discretion to state and local leadership |

| Good stewardship of resources | Balance immediate resource allocation decisions against known ongoing missions and likely future requirements |

Abbreviations: ASPR, Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response; CDC, Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention.

To support states, federal leaders should recognize the role and perspective of state leaders, as they are likely to be best informed about their situations. At the same time, federal leaders are likely to be able to compare the relative needs when several states make requests for assistance. Given this complex reality, both state and federal governments have valuable perspectives to offer regarding the amount of resources that each state needs to respond to a disaster and the amount that the federal government should offer in assistance. Accordingly, the decision about the amount of scarce resources to be given to each state should consider that states with the greatest needs may experience a reduced ability to govern and communicate and, therefore, may submit requests after states with lesser needs.

Recognizing the important partnership between federal and state leaders in addressing disasters most effectively, the National Response Framework specifies that operational planning needs to integrate federal departments and agencies and other national-level partners to provide the right resources at the right time to support state response operations.2

Allocation Criteria and Scoring System

The substantive and procedural values and concepts consistent with the principle of federalism provided the basis for 15 allocation criteria that the work group proposed federal decision makers might use to guide decisions regarding allocation of scarce federal public health and medical resources. The criteria and their definitions are summarized in Table 4. Initially, the work group assigned equal weight to each of the criteria and applied a scoring system to quantify the criteria and to provide a rigorous approach to the allocation decisions. With use of the scoring system, each affected state would be evaluated according to the 15 allocation criteria on a scale of 0 to 2, to produce a total score for each state. Prioritizing among states would be based on the total score each state received when assessed against all 15 criteria. States would not be compared with one another according to any individual criterion. The rating specifications and scoring are also shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

| Criterion and Definition | Rating Specifications Rate 0–2 as noted |

State Score |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Size of population affected by the disastera | ||

| Consistent with federal agency missions of protecting the public from harm and providing aid to those who are least able to help themselves, allocation decisions should consider the number of affected residents in a state. This criterion will take into consideration the number of affected residents in a state. This criterion will be calculated by estimating the percentage of population harmed in the affected area, and multiplying by the size of the population in the affected area. | 0: up to 33% of Nb |

|

|

| 1: 34%-66% of N | |||

| 2: 67%-100% of N | |||

| 2. | Size of population (in state/counties)a | ||

| In the early stage of a disaster, situational awareness will often limit information about absolute numbers of harmed and threatened lives. Therefore, allocation decisions will also consider the size of the population in an affected area. Often a disaster will affect some counties in a state rather than an entire state. Where this is known to be the case, the size of the population in affected counties will be used. | Specify size of state/county population in millions: |

|

|

| 0: 0≤10 | |||

| 1: 10≤15 | |||

| 2: 15+ | |||

| 3. | Extent to which affected people are likely to benefit from medical interventiona | ||

| As with allocation decisions at any level, whether among individual patients, segments of the population, or political entities, public health and medical resources are likely to be most effectively utilized if they are allocated to those who are expected to benefit most from receiving resources. The reasoning is that the chance of survival for those who are fatally wounded and those who are slightly wounded is not likely to be significantly altered by deferring treatment. A strategy that prioritizes resources for those most likely to benefit, improves chances for survival overall.30 | 0: None of the medical conditions are expected to benefit from intervention |

|

|

| 1: Some of the medical conditions are expected to benefit from intervention | |||

| 2: Most medical conditions are expected to benefit from intervention | |||

| 4. | Size of population anticipated to be at additional risk of harma | ||

| Allocation decisions will take into consideration the extent to which the disaster is anticipated to cause additional harm as it unfolds. This criterion will be calculated by estimating the percentage of population that is anticipated to be harmed in the affected area and multiplying by the size of the population in the affected area. | 0: ≤33% of N |

|

|

| 1: 34%-66% of N | |||

| 2: 67%-100% of N | |||

| 5. | Size of the special needs population affecteda | ||

| To ensure that population-based allocation decisions do not exacerbate the condition of individuals with special medical needs in an affected state, the percentage of individuals with special needs among a state’s population will be considered. These individuals who require assistance for medical, mental, or psychological disabilities, and whose health depends on regular contact with the health care system, are at risk for additional harm if medical resources are unavailable to them in disaster situations. This criterion will be calculated by estimating the percentage of the population with special needs in the affected area, and multiplying by the size of the population in the affected area.11 | 0: ≤10% of N |

|

|

| 1: 10%≤20% of N | |||

| 2: >0% of N | |||

| 6. | Size of the population below the poverty thresholda | ||

| To ensure that population-based allocation decisions do not exacerbate the condition of individuals with limited financial and other resources, the prevalence of poverty in the affected state will be considered. Poverty is a useful summary indicator of several factors that put individuals at risk for poorer health status and worse health outcomes including less access to care, reduced health literacy, poorer management of chronic disease, lower rating of self-reported health status, and shorter life expectancy. Information about the percent of the population below the poverty threshold is readily available from census data and can thus be quickly used in the decision process. | 0: 0≤10% of N |

|

|

| 1: 10%≤20% of N | |||

| 2: >0% of N | |||

| 7. | Size of medically underserved areas/populationsa | ||

| Allocation decisions will consider medically underserved populations so as to not further disadvantage them. The medically underserved population areas within the affected state will be identified using the index of medical underservice. The 4 components of the index are the percentage of the population below poverty; the percentage of the population that is elderly; the infant mortality rate; and the availability of primary care physicians.31 | 0: 0≤10% of N |

|

|

| 1: 10%≤20% of N | |||

| 2: >0% of N | |||

| 8. | Degree of destruction of medical and public health infrastructure and resources | ||

| Allocation decisions will take into consideration the degree of destruction of the medical infrastructure (eg, hospital, out of hospital behavioral health) and the ability to perform public health functions (eg, epidemiologic investigations, laboratory services, public information) in the affected state as a result of the disaster, as states with greater destruction are less able to meet needs without assistance. States with greater destruction will receive a higher rating. | 0: No destruction |

|

|

| 1: Some destruction | |||

| 2: Extensive destruction | |||

| 9. | Ease of rapid delivery of federal resources | ||

| Allocation decisions will take into consideration the degree of destruction of roads, rail lines, airports, and other critical infrastructure for the purpose of evaluating the feasibility of federal asset delivery. Severe damage may diminish the likelihood that medical resources can be delivered in a sufficiently timely fashion to save lives that are in imminent danger. States with greater destruction in these areas will receive a lower rating on this element unless the effect of such damage on achievement of operational goals can be mitigated. Note: the positioning of resources for an event with prior warning (eg, hurricane) will occur in advance of the decisions regarding scarce resource allocation. |

0: Deliverable in .24 h |

|

|

| 1: Deliverable in 12–24 h | |||

| 2: Deliverable in ,12 h | |||

| 10. | Degree of destruction of local infrastructure | ||

| Allocation decisions will take into consideration the degree of destruction of roads, rail lines, and airports for the purpose of evaluating the ability of the population to exit the disaster area. The inability of the population to exit will increase the need to provide medical aid. It is recognized that this concern leads to scoring that seems contradictory to the previous allocation criterion. Decision makers must weigh these 2 consequences of destruction of infrastructure independently, recognizing that they may cancel each other out. |

0: No destruction |

|

|

| 1: Some destruction | |||

| 2: Extensive destruction | |||

| 11. | Likelihood that allocated federal public health and medical resources can be used to meet needs | ||

| Allocation decisions will take into consideration the ability of affected states to deploy and utilize the resources once received. States with the ability to quickly and effectively utilize the federal public health and medical resources will receive a higher rating on this criterion. | 0: Poor match |

|

|

| 1: Moderate match | |||

| 2: Good match | |||

| 12. | Access to alternative sources of aid | ||

| Allocation decisions will take into consideration the ability of affected states to seek and provide mutual assistance prior to seeking federal assistance. States already receiving assistance from other states under the emergency management assistance compact (EMAC)1 that substantially address the resource gap receive a lower rating on this element. | 0: Receiving EMAC aid that substantially addresses requested resource gap |

|

|

| 1: EMAC request for resources and/or adjudication of request are pending | |||

| 2: Little or no EMAC aid available to meet requested gap | |||

| 13. | Degree of critical national priorities affected | ||

| Allocation decisions will take into consideration critical national priorities beyond those of the individual state. Those states where a disaster is expected to have an effect on federal interests such as crucial transportation, energy, communication, and/or nuclear safety resources will receive a higher rating on this element. | 0: No critical national priorities affected |

|

|

| 1: Some critical national priorities affected | |||

| 2: Many critical national priorities affected | |||

| 14. | US Health and Human Services assistance will potentiate asset coordination with other federal aid efforts | ||

| Allocation decisions will take into consideration the extent to which federal efforts can be coordinated to work synergistically. States in which resources can be coordinated will receive a higher rating on this element. | 0: No coordination |

|

|

| 1: Some coordination | |||

| 2: Extensive coordination | |||

| 15. | Equal consideration of each state | ||

| At the same time that the size of the population in an affected state should be taken into account to evaluate the greatest aggregate good, each state affected by a disaster deserves equal consideration by the federal government. This allocation criterion functions in a manner analogous to congressional representation: while each state has proportional representation in the House of Representatives based the size of its population, it has equal representation in the Senate. On this criterion, each affected state gets the same rating. | Each state gets 2 points |

|

|

| Total Score = |

|

||

For all population-based criteria (1 to 7), decision makers should use a consistent approach (either state or county data) in scoring.

N=number of people in state/county.

Stakeholder Engagement Workshops

We presented the criteria and the scoring system to stakeholders to test the validity of the proposed approach to federal resource allocation decision making. The engagements included the following groups: (1) disaster preparedness and emergency management experts attending the annual Integrated Medical, Public Health, Preparedness and Response Training Summit (ITS)27; bioethicists attending the annual meeting of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities (ASBH)29; and attendees of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Bioethics Interest Group.28

Approximately 130 disaster response experts participating in the ITS27 chose to attend a breakout session in which the allocation framework was discussed. Participants were asked to rate, using audience response technology, each of the allocation criteria on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “extremely important,” to “not important, can be eliminated.” Six criteria (1,3,8,10–12) had the highest percentage of people who ranked them as extremely important, very important, or important (Table 4). The attendees also rated 2 of the criteria (9 and 15) as unimportant and could be eliminated (Table 4). The remaining criteria received ratings of moderate importance. These findings support the face validity of most of the criteria among disaster response experts. Open-ended comments supported the finding that the respondents thought that some criteria were more important than others, suggesting that the criteria should not be weighted equally.

The engagements with the ASBH and the NIH Bioethics Interest Group used a discussion format, rather than audience-response technology. During the workshops, we provided the background of the problem and the proposed framework and a hypothetical disaster scenario to focus the discussion of the criteria and asked participants to deliberate about the following:

the usability and acceptability of the allocation criteria

whether any other criteria should be added

the utility of the proposed scoring system.

Participants at both of these meetings commented that the framework provided ethically useful guideposts for allocating scarce federal resources and that the criteria reflected the procedural and substantive values relevant to ethical disaster planning and response. However, many respondents also found the criteria to be vague or cumbersome to apply in the context of the hypothetical disaster scenario. They also found the criteria difficult to apply when the data needed to score them were not available. Some agreed with the stakeholders from the ITS and suggested that the criteria should not be weighted equally.

Logic Model

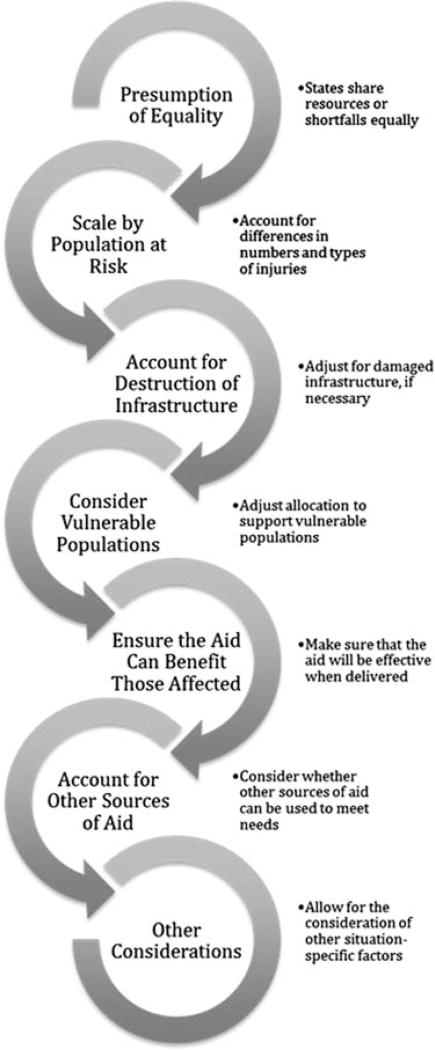

Following these stakeholder engagements, we consulted the analytic decision support group of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) regarding next steps in the development of the framework, given their expertise in modeling allocation decision making. The BARDA group proposed a logic model to illustrate the decision-making process using the criteria proposed in the original framework (Figure). One difference, however, is that while the original criteria were focused on specific resources, the logic model can be applied to specific resources or to resources more generally. The logic model combines a number of the original criteria and focuses on a qualitative rather than a quantitative approach.

Figure. Logic Model.

Original work developed in collaboration with modeling experts from the Analytic Decision Support Group, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (Appendix).

Moreover, the logic model retains the criteria identified in the original framework, which stakeholders agreed were ethically relevant, but organizes the criteria in the form of a decision procedure that may be easier to employ. In this approach, the logic model addresses the concern raised by stakeholders that quantitative scoring of the criteria was cumbersome and that it was difficult to use when situational awareness is limited. It also addresses concerns raised by the BARDA group that a quantitative approach implies a level of precision that is not possible in this type of decision making. The logic model’s qualitative approach does not attribute equal weight to the criteria; instead, it allows decision makers to weight relevant criteria differently, as appropriate to the circumstances of the disaster.

The logic model starts with the presumption of equal allocation, which is a modification of criterion 15 from the original framework that specified equal consideration for each state. The presumption is that all affected states are entitled to the same allocation of the scarce federal resources under the same circumstances. This provisional allocation may indicate that each state gets the same amount of the resource or that each state’s request is reduced by the same amount.

If sufficient differences in need occur, rendering an equal allocation of the scarce resource unfair, then the provisional allocation should be modified based on the considerations in subsequent steps of the logic model. Federal decision makers would continue to the next steps in the logic model for needed refinements to equal allocation.

At the second step of the logic model, decision makers modify the provisional allocation according to the population at risk. This step combines criteria 1 through 4 from the original framework. While the scarce resource need not be allocated solely based on the number of people affected by the disaster, the need for the resource and the potential for the resource to benefit people are both highly correlated with the number of people affected. The types and severity of injuries and the potential for follow-on injuries are both legitimate considerations for allocating the resources. Different types of scarce resources do not need to be equally distributed if it would produce an unfair or inefficient allocation. For example, if a state has a high number of burn injuries while another has a large number of crush injuries, assigning each state an equal number of burn and crush injury teams would not be helpful or ethical. If no meaningful difference in the population at risk is found in the affected states, no adjustment to the provisional allocation is needed at this step.

At the third step of the logic model, decision makers will make modifications to account for destruction of infrastructure (including critical infrastructure and key resources). This step combines criteria 8 and 10 from the original framework and adds critical infrastructure and key resources that have a local impact. For example, if a nuclear power plant is damaged during an earthquake, local impact will occur from radiation exposure; also, national implications will arise because of decreased energy production. If no meaningful difference is found in the degree of destruction of infrastructure between states, then no adjustment to the provisional allocation is needed at this step.

The fourth step of the logic model considers vulnerable populations. In the original framework, criteria 5 through 7 considered special needs populations. With the logic model the language was changed to vulnerable populations to align terminology with existing guidance.32 If the difference in vulnerable populations is significant between different states, the allocation of the scarce resources may need to be adjusted to make the allocation more equitable. Potential vulnerable populations may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Individuals with pre-existing access needs or functional, medical, mental health, or psychological needs for care, treatment, or pharmaceuticals,32

Segments of the population below the poverty threshold, and

Medically underserved populations.

If no meaningful difference in vulnerable populations exists among the states, no adjustment is needed to the provisional allocation at this step.

The fifth step in the logic model considers whether the scarce resource is likely to benefit those affected. This step combines criteria 9 and 11 from the original framework. Because the purpose of resource allocation is to help those affected by the disaster, the resources that are provided must be pertinent to the local conditions. If local conditions prevent a scarce resource from being effectively delivered or used due to destruction of required infrastructure, damage to transportation networks that negates the ability of the aid to arrive in a timely manner, or other conditions that render the aid unhelpful, then the provisional allocation must be adjusted so the scarce resource can be sent and used effectively elsewhere. As an example, medical teams that are meant to augment hospitals may not be used effectively if the hospitals are severely damaged. In that circumstance, the teams may be better deployed to a state that can use this scarce resource more effectively. A separate determination would need to be made about whether self-sufficient medical teams are available for deployment to the state that suffered destruction of its hospitals. In making this assessment, federal leaders acknowledge the perceptions and perspectives of state leaders regarding their needs by taking into consideration state requests.

The sixth step of the logic model accounts for the availability of other sources of aid, combining criteria 12 and 14 from the original framework. Federal agencies do not provide aid in a vacuum. When a particular federal resource or resources more generally are scarce, the allocation decision should take into account other aid being made available to affected states. If a state has an internal or other non-federal source for the needed capability, the state’s need for the federal resource is decreased. In this case, it would be fairer to decrease the amount of the resource provided to that state and increase the allocation to states that do not have an external source of aid.

The last step of the logic model addresses other considerations (including critical national priorities), which is criterion number 13 in the original framework. These considerations may include White House policies, statutes, regulations, and critical infrastructures and key resources. Examples include presidential direction with regard to international evacuation; legislation regarding spending of disaster relief dollars; US Food and Drug Administration regulations with regard to international donations of food and medications; and damage to critical infrastructures that do not have a local public health and medical impact but could have national implications such as a data center that supports financial services. When analyzing their decisions, federal decision makers should consider factors that have not yet been addressed. If the allocation resulting from the 6 previous steps appears unfair, given such considerations, it should be revised.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

This framework seeks to provide an ethical approach for strategic decision making regarding allocation of scarce public health and medical resources to affected states. This allocation framework begins to resolve a gap that was identified during the 2011 national-level exercise that used a New Madrid seismic zone earthquake scenario. It was noted that there was and still is no, “…system that would verify and protect resources for dissemination [sic], based on a prioritization scale.” Thus, it was recommended that ASPR, “Develop a system to ensure resources are not overly disseminated [sic] to jurisdictions, states, or regions based solely on their ability to communicate easier [sic] than harder hit areas.”33

Allocation of federal public health and medical resources is different from the crisis standards of care framework developed in 2009 by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) at the request of the ASPR.20 The IOM work was motivated by the potential for the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic to reach a severity comparable to the catastrophic Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918, and it focused on “…adjusting practice standards” and “…shifting the balance of ethical concerns to emphasize the needs of the community rather than the needs of individuals”.20 While the IOM framework focuses on the shift in clinical practice from individual patients to the larger community of persons affected by the disaster, the focus of the modified framework provided here is the development of a well-reasoned ethical basis for resource allocation in a multitiered government such as the US federal system.

The 15 allocation criteria that were proposed in the original framework developed by the working group drew on well-established substantive and procedural values in medical ethics and concepts consistent with the principle of federalism. The working group then developed a scoring system based on the criteria. During engagement with disaster preparedness and emergency management experts and bioethicists, it was generally acknowledged that in disaster situations precise information would not be available to decision makers. As a result, using a mathematical formula as a basis for allocations would not be defensible, as it would imply that the process relied on precise calculations rather than on judgment informed by the best available information. By contrast, the logic model incorporates the values-based framework into an iterative decision process that can inform the gestalt of federal decision makers. Although the logic model was developed to apply to decisions regarding allocation of specific scarce resources (where decision makers know that particular resources are insufficient to meet needs), decision makers can also use the framework and logic model to make decisions about fair allocation of resources in general, regardless of whether a particular resource is scarce.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2014.9

References

- 1.National Emergency Management Association. [Accessed May 30, 2013];Emergency management assistance compact website. http://www.emacweb.org/

- 2.Federal Emergency Management Agency, US Department of Homeland Security. The National Response Framework. 2. Washington, DC: Department of Homeland Security; May, 2013. [Accessed July 31, 2013]. http://www.fema.gov/national-response-framework. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett DJ, Taylor HA, Hodge JG, Jr, Links JM. Resource allocation on the frontlines of public health preparedness and response: report of a summit on legal and ethical issues. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(2):295–303. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gostin LO, Powers M. What does social justice require for the public’s health? Public health ethics and policy imperatives. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(4):1053–1060. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinlaw K, Barrett DH, Levine RJ. Ethical guidelines in pandemic influenza: recommendations of the ethics subcommittee of the advisory committee of the director, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3(suppl 2):S185–S192. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181ac194f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotalik J. Preparing for an influenza pandemic: ethical issues. Bioethics. 2005;19(4):422–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2005.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Center for Ethics in Health Care, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs. [Accessed July 31, 2013];Meeting the challenge of pandemic influenza: ethical guidance for leaders and health care professionals in the Veterans Health Administration. 2010 Jul; http://www.ethics.va.gov/activities/pandemic_influenza_preparedness.asp.

- 9.Persad G, Wertheimer A, Emanuel EJ. Principles for allocation of scarce medical interventions. Lancet. 2009;373(9661):423–431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson AK, Faith K, Gibson JL, Upshur RE. Pandemic influenza preparedness: an ethical framework to guide decision-making. BMC Med Ethics. 2006;7:E12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vawter DE, Garrett JE, Gervais KG, et al. For the Good of Us All: Ethically Rationing Health Resources in Minnesota in a Severe Influenza Pandemic. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Department of Health; 2010. [Accessed January 23, 2014]. http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/ethics/ethics.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verweij M Working Group One. Addressing Ethical Issues in Pandemic Influenza Planning. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; Oct 26, 2006. [Accessed July 31, 2013]. Equitable access to therapeutic and prophylactic measures. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/cds_flu_ethics_5web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics, Pandemic Influenza Working Group. Stand on guard for thee: ethical considerations in prepardeness planning for pandemic influenza. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics, Pandemic Influenza Working Group; Nov, 2005. [Accessed July 31, 2013]. http://www.jointcentreforbioethics.ca/people/documents/upshur_stand_guard.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLean M. [Accessed July 31, 2013];Ethical preparedness for pandemic influenza: a toolkit website. 2012 Oct; http://www.scu.edu/ethics/practicing/focusareas/medical/pandemic.html.

- 15.Roberts M, DeRenzo E. Ethical considerations in community disaster planning. In: Phillips S, Knebel A, editors. Mass Medical Care With Scarce Resources: A Community Planning Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caro JJ, Coleman CN, Knebel A, DeRenzo EG. Unaltered ethical standards for individual physicians in the face of drastically reduced resources resulting from an improvised nuclear device event. J Clin Ethics. 2011;22(1):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilner J. Who Lives? Who Dies? Ethical Criteria in Patient Selection. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuschner WG, Pollard JB, Ezeji-Okoye SC. Ethical triage and scarce resource allocation during public health emergencies: tenets and procedures. Hosp Top. 2007;85(3):16–25. doi: 10.3200/HTPS.85.3.16-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winslow G. Triage and Justice: The Ethics of Rationing Life-Saving Medical Resources. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine. Guidance for Establishing Crisis Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations: A Letter Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed August 2, 2013];Crisis and emergency risk communication (CERC) website. http://www.bt.cdc.gov/cerc/

- 22.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Communicating in a Crisis: Risk Communication Guidelines for Public Officials. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2002. [Accessed August 2, 2013]. http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Risk-Communication-Guide-lines-for-Public-Officials/SMA02-3641. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchanan J. Federalism and fiscal equity. Am Econ Rev. 1950;40(4):583–599. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. A Report to the President for Transmittal to the Congress. Washington, DC: Commission on Intergovernmental Relations; Jun, 1955. Natural disaster relief; p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed August 2, 2013];Funding and guidance for state and local health departments website. http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/coopagreement.htm.

- 26.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed August 2, 2013];Hospital preparedness program: funding and grant opportunities website. http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/Pages/funding.aspx.

- 27.Danis M, Hansen C, Knebel A. Developing guidance to support allocation by HHS of scarce federal resources in disaster settings: an opportunity for stakeholder input. Paper presented at: Integrated Medical, Public Health, Preparedness and Response Training Summit; Nashville, TN. May 21–25, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danis M, Sharpe V, Knebel A. Allocating scarce federal public health and medical resources in disaster situations: a framework for ethical decision making; Paper presented at: National Institutes of Health Bioethics Interest Group; Bethesda, MD. Jan 7, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharpe V, Danis M, Knebel A. Draft guidance on allocating scarce federal resources in disaster situations: a framework for ethical decision making; Paper presented at: American Society for Bioethics and Humanities Annual Meeting; Washington, DC. Oct 18–21, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker R, Strosberg M. Triage, equality: An historical reassessment of utilitarian analyses of triage. Kennedy Ins. Ethics J. 1992;2(2):103–123. doi: 10.1353/ken.0.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed August 2, 2013];Find shortage areas: medically underserved areas/populations by state and county website. http://muafind.hrsa.gov/

- 32.Federal Emergency Management Agency, US Department of Homeland Security. [Accessed August 2, 2013];Guidance on planning for integration of functional needs support services in general population shelters. 2010 Nov; http://www.fema.gov/pdf/about/odic/fnss_guidance.pdf.

- 33.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, US Department of Health and Human Services. National level exercise: improvement plan. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; Sep 30, 2011. item 4.2. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.