Abstract

Background

Electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs) rely on computer algorithms to extract data from electronic health records (EHRs). On behalf of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), we sought to develop and test eCQMs for rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Drawing from published ACR guidelines, a working group developed candidate RA process measures and subsequently assessed face validity through an interdisciplinary panel of health care stakeholders. A public comment period followed. Measures that passed these levels of review were electronically specified using the Quality Data Model, which provides standard nomenclature for data elements (category, datatype, value sets) obtained through an EHR. For each eCQM, 3 clinical sites using different EHR systems tested the scientific feasibility and validity of measures. Measures appropriate for accountability were presented for national endorsement.

Results

Expert panel validity ratings were high for all measures (median 8–9 out of 9). Health system performance on the eCQMs was 53.6% for RA disease activity assessment, 69.1% for functional status assessment, 93.1% for disease modifying drug (DMARD) use and 72.8% for tuberculosis screening. Kappa statistics, evaluating whether the eCQM validly captured data obtained from manual EHR chart review, demonstrated moderate to substantial agreement (0.54 for functional status assessment, 0.73 for tuberculosis screening, 0.84 for disease activity, and 0.85 for DMARD use).

Conclusion

Four eCQMs for RA have achieved national endorsement and are recommended for use in federal quality reporting programs. Implementation and further refinement of these measures is ongoing in the ACR’s registry, the Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE).

Quality measurement in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a national priority in healthcare. Stakeholders convened by the National Quality Forum recently selected RA as one of the top 20 Medicare chronic conditions for quality measure development (1). This designation resulted from the relatively high prevalence of RA, which affects 1.3 million Americans, and its significant morbidity and costs (2). Moreover, previous quality measurement efforts have identified important gaps in health care for RA. For example, socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities exist in disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) use, and there is significant variation in implementation of best practices for ensuring patient safety and optimizing disease control through the use of standardized outcome measures (3, 4).

Over the last decade, quality measures in RA have largely relied on two data sources: administrative billing claims and chart reviews. Each of these methods have limitations, including the restricted clinical information available in claims and the resource-intensive nature of chart review. Moreover, while these approaches have enabled retrospective performance measurement in RA, they have been less conducive to providing information to clinicians in real-time to support rapid cycle quality improvement. To address these limitations, there is increasing interest in leveraging electronic health records (EHRs) to develop electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs). eCQMs are a new type of quality measure that rely on automated extraction of information from the EHR. Coupled with local data analytics or innovations such as nationally Qualified Clinical Data Registries, which centrally analyze and feedback data to practices, eCQMs can be used as tools to drive continuous quality improvement.

In this study, we sought to develop and test eCQMs for RA using a multistakeholder process with input from an interdisciplinary team of clinicians, patients, payers, and medical informaticists. Using practices with different EHR systems, we also sought to study the early feasibility and reliability of RA eCQMs before submission to the National Quality Forum for endorsement and implementation in RISE.

METHODS

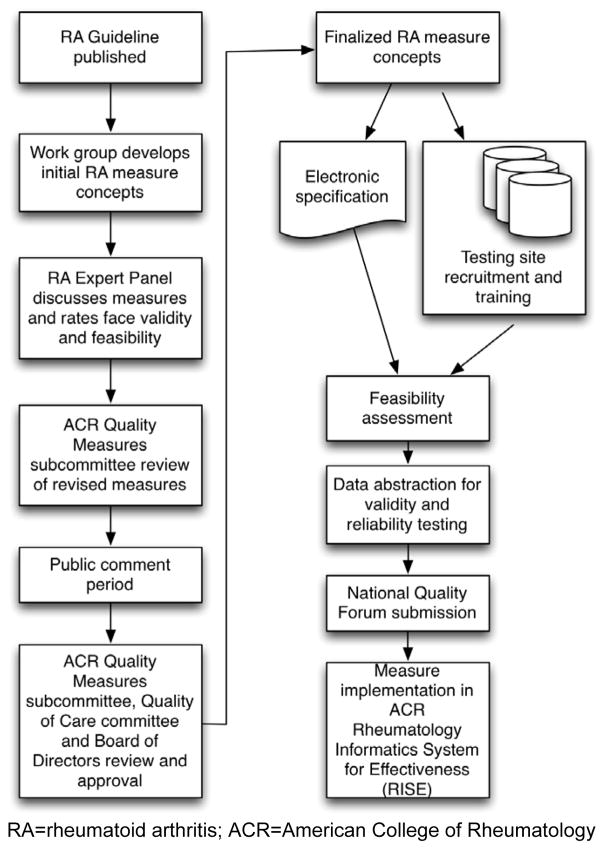

The ACR’s overall process for developing eCQMs is outlined in Figure 1 and also described in detail elsewhere (5). Here we describe how this process was applied to develop RA eCQMs.

Figure 1. Overview of the American College of Rheumatology’s Rheumatoid Arthritis electronic clinical quality measure development program.

RA=rheumatoid arthritis; ACR=American College of Rheumatology

Measure conceptualization

A working group (J.Y., G.S., S.D., T.N., D.L., J.S., M.G., E.N.) was assembled to draft measures for RA based on the most recent ACR guideline (6).. We reviewed guidelines referencing RA, reviewed and characterized the level of scientific evidence supporting various measure concepts, and also considered harmonization with existing measures. For this latter portion, our goal was to avoid duplication with existing measures in national reporting programs.

The working group drafted potential eCQMs concepts in an iterative manner. Although both process measures (e.g. what clinicians do in providing care) and outcome measures (e.g. health outcomes that result from care) were considered, the working group decided to proceed with process measures since research evaluating risk-adjustment models for RA was not available. We drafted eCQMs concepts in an IF, THEN format and presented these concepts to an Expert Panel for review (7).

Interdisciplinary consensus ratings

Nominations were sought for a multistakeholder panel of experts on RA. In addition to rheumatologists in both academic and community practice, we included patient and payer representatives. A member from each of the Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals the American College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgery, were also invited (see Appendix). Panel members did not receive payment for participation. The Chair of the panel and the majority of its members (≥50%) had no financial conflicts of interest with any product made for RA.

Expert panel meetings and ACR Committee Review and Public Comment

Expert panel members participated in a webinar introducing the project. Members received a summary of the RA measure concepts under consideration. Included were references to corresponding sections of the ACR RA guideline and a summary of existing analogous measures in national reporting programs. For example, information on specifications and performance data on the National Committee on Quality Assurance’s DMARD measure, implemented over the last decade using administrative claims to assess health plan performance, were provided (3).

We used a modification of the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method to have expert panel members rate the measures (8). Details about our methods for conducting this session and analyzing the results are provided elsewhere (5). Measures that were rated as valid and feasible were reviewed by the ACR Quality Measures Subcommittee, and distributed for public comment. Public comments informed revisions, and the measures were sent to the ACR Quality of Care Committee and Board of Directors for final approval.

Electronic specification

To convert measure concepts to eCQM format, we used a multi-step process that aligned with current national standards, including the Health Quality Measures Format. RA eCQMs were first specified using the Measure Authoring Tool (MAT) and Quality Data Model (QDM) (9). We then worked with a clinical informaticist (G.W., see Appendix) who used QDM elements to elaborate all possible code sets to represent measure concepts in EHRs, including International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision (ICD9, ICD10), Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT), Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), and RxNorm.

There were two instances where uniform EHR nomenclature was not available in current terminology (“RA disease activity measure score”, “RA functional status measure score”); the ACR submitted requests to have these added to the Value Set Authority Center at the National Library of Medicine. Once the code lists were finalized, physicians from the working group worked in pairs to review all codes, using clinical judgment to assess their appropriateness for inclusion; any discordance was adjudicated through discussion. The MAT was then used to build the final eCQMs.

eCQM field-testing

For each eCQM, we recruited 3 sites using different EHR products to test the measures. Data elements for all eCQMs were extracted from EHRs using computer programming, and therefore by virtue of automation, this process is repeatable (reliable); however, because data algorithms must be implemented accurately, testing focused on the technical feasibility and concurrent validity of each measure, described below (5). Each site first completed a feasibility survey and then worked with local information technology staff to build the RA eCQM extraction algorithms. This required review of the eCQMs specifications, including measure background information, required data elements, measure logic and measure calculation instructions, human-readable formats of the measure, as well as a detailed spreadsheet with value sets (i.e., code sets) for each measure.

We decided a priori to perform feasibility testing for 3 key data elements: disease activity score, functional status score, and RA diagnosis. Sites completed a detailed survey assessing data availability and accuracy (e.g. is information for the eCQM collected in the EHR and is that information correct?), data standards (e.g. are standard value sets used to collect the data elements?), and operational or workflow issues (e.g. how is the data element entered in the EHR?). Both quantitative data, which included the National Quality Forum feasibility assessment scale (described previously, (5)) and qualitative information outlining challenges to eCQM implementation were collected.

We also assessed concurrent validity, or whether the information from the EHR data pull was similar to the information that a human abstractor obtains by reading the front-end of the EHR. Rheumatology providers in each practice performed the front-end EHR chart review. We used Kappa statistics to determine whether, for each measure and site, the manual chart review and automated EHR data extracts identified the same patients as meeting the numerator of each measure. In our analyses, the manually extracted data was used as the “gold standard” for both the numerator and denominator of each measure. In these analyses, Kappa=1.0 when the automated EHR query agrees exactly with data obtained through manual chart extraction, and Kappa=0 when the agreement appears entirely due to chance. For the denominator components, we calculated the percentage agreement between the chart review and automated EHR extracts.

In addition, we calculated the sensitivity and specificity for the numerator of the performance scores, again using chart review as the gold standard. In these analyses, true positives were the individuals with RA who received recommended care based on the chart review, and the sensitivity was the proportion of those true positive patients who were correctly identified as receiving recommended care in the computer extract. True negatives were those who did not receive recommended care in the chart review, and the specificity is the proportion of the true negative patients who we identified as not receiving recommended care in the EHR extract.

All data were analyzed at the individual patient level. For each validation project, a simple random sample was constructed that was powered for the analyses.

Submission for national endorsement and implementation in RISE

Because a goal of the ACR eCQM development project was to contribute toward a coherent performance measurement strategy for U.S. rheumatologists, an important priority was to submit measures for national endorsement. RA eCQMs were therefore submitted to the National Quality Forum. Measures were also implemented in the ACR’s Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) registry.

RESULTS

Below we present the results of each phase of the eCQM development work. Our results, including the evidence summaries, reflect the data included for the national endorsement process.

Measure conceptualization

The working group drafted six measure concepts relevant to RA (Table 1). Below, we briefly review the rationale and scientific evidence supporting each measure. In the context of this scientific evidence, we also discuss the reasoning of the working group in defining specific aspects of each measure.

Table 1.

Rheumatoid arthritis quality measure concepts, numerators and denominators.

| Measure Title | Brief description of measure | Measure properties | Denominator | Numerator | Numerator or Denominator Detail | Exclusions | Type of score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Disease Activity | Percentage of patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of RA and ≥50% of total number of outpatient RA encounters in the measurement year with assessment of disease activity using a standardized measure. | Type of measure: Process Data source: Electronic clinical data; electronic health record Level of analysis: Individual clinician Time period: 12 months |

Patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis seen for two or more face-to-face encounters for RA with the same clinician during the measurement period. | # of patients with >=50% of total number of outpatient RA encounters in the measurement year with assessment of disease activity using a standardized measure. | Numerator Detail: RA disease activity measurement tools must include one of the following instruments:

|

None | Rate/proportion, with higher rate meaning better quality |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Functional Status Assessment | Percentage of patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of RA for whom a functional status assessment was performed at least once during the measurement period | Type of measure: Process Data source: Electronic clinical data; electronic health record Level of analysis: Individual clinician Time period: 12 months |

Patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis seen for two or more face-to-face encounters for RA with the same clinician during the measurement period. | # of patients in the measurement year with functional status assessments using a standardized measure. | Numerator Detail: Functional status can be assessed by using one of a number of instruments, including:

|

None | Rate/proportion, with higher rate meaning better quality |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) Therapy | Percentage of patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of RA who are prescribed a DMARD in the measurement year | Type of measure: Process Data source: Electronic clinical data; electronic health record Level of analysis: Individual clinician Time period: 12 months |

Patients age 18 years and older with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis seen for two or more face-to-face encounters for RA with the same clinician during the measurement period | Numerator Detail: All available DMARDs in the measurement period. For 2014 this was: Biologic agents: abatacept, Adalimumab, anakinra, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, tocilizumab Non-biologic agents: azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, gold, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, minocycline, penicillamine, sulfasalazine Small molecule: tofacitinib |

Patients with a diagnosis of HIV; patients who are pregnant; or patients with inactive Rheumatoid Arthritis. | Rate/proportion, with higher rate meaning better quality | |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Tuberculosis screening | Percentage of patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of RA who have documentation of tuberculosis (TB) screening performed within 12 months prior to receiving a first course of therapy using biologic drugs. | Type of measure: Process Data source: Electronic clinical data; electronic health record Level of analysis: Individual clinician Time period: 12 months |

Persons 18 years and older with a diagnosis of RA who are seen for at least one face-to-face encounter for RA and are newly started on biologic therapy during the measurement period. | Any record of TB testing documented or performed (PPD, IFN-gamma release assays, or other appropriate screening or treatment) in the medical record in the 12 months preceding the biologic DMARD initiation. | Denominator Detail: For the purposes of this measure, patients who are newly started on biologic therapy are those who have been prescribed a biologic DMARD during the measurement period and who were NOT prescribed a biologic DMARD in the 12 months preceding the encounter where the biologic drug was started. Biologic DMARDs included: abatacept, adalimumab, anakinra, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, tocilizumab. |

None | Rate/proportion, with higher rate meaning better quality |

1. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Disease Activity

The paradigm of RA management has undergone a significant transformation with the introduction of both new drugs and scientific evidence demonstrating improved outcomes when these drugs are used in conjunction with a treat-to-target strategy (10, 11). The concept of treating-to-target relies on adjusting therapy until a state of remission (or low disease activity) is achieved. Despite widespread endorsement from the rheumatology community, evidence suggests a significant gap in care in this area (4).

Evidence consists of important clinical trials of different treat-to-target strategies anchored on disease activity assessments showing better RA outcomes in the treat-to-target groups (12–15). Additionally, in an observational study involving 1,297 individuals, achievement of recommended disease targets was associated with improved physical function, health-related quality-of-life, and reduced hospitalizations (16). Finally, a large observational study in the Geisinger Health System demonstrated that implementing RA disease activity assessments using health information technology tools was associated with statistically significant improvements in RA disease control over time (17). This latter study is the only one that has found a link between the process of measuring and displaying RA disease activity and improved outcomes; the remainder use disease assessments as part of a larger treat-to-target strategy.

The working group recommended a measure requiring use of a validated outcome tool, as recommended by the ACR (6, 18): the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), Disease Activity Score with 28-joint counts (DAS erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein), Patient Activity Scale (PAS I and II), Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data with 3 measures (RAPID 3), and Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI). Each measure is an accurate reflection of disease activity; is sensitive to change; discriminates well between low, moderate, and high disease activity states; has remission criteria; and is feasible to perform in clinical settings. In other words, these measures can support a treat-to-target strategy in clinical practice (18). While starting with these measures, the working group also recommends that this list be periodically updated by the ACR to incorporate the latest advances in RA outcomes measurement.

Furthermore, the working group recommended that these measures be used in a majority (≥50%) of RA encounters. The threshold of ≥50% was chosen for several reasons. First, patients sometimes have an encounter for RA to address an acute issue (e.g. infection, drug adverse effect); a disease activity measure may not be relevant at all encounters. Second, the working group recognized that instituting measures in clinical practice requires complex changes in clinical workflow. Experience at leading rheumatology centers suggests that achievement of 100% performance is not attainable and may even have unintended consequences in diverting resources from other clinical activities (17). In response to these issues, the working group recommended RA disease activity measurement occur at a majority (≥50%) of encounters.

The working group considered other evidence suggesting gaps in care that justify use of the measure. Data from the ACR’s Rheumatology Clinical Registry (RCR), used by rheumatologists for the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), suggests room for improvement on this measure. In 2011, participating rheumatologists had a performance rate of 43.4% on a measure requiring assessment of disease activity at least once per year; performance has increased each year (43.4% in 2011, 54.4% in 2012, 81.0% in 2013). Other studies also suggest a gap in performance. For example, one study from an academic medical center found that RA disease activity was only recorded in 29.0% of visits (19). In addition, although information on health care disparities are limited, data from a large US registry using the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) also found important differences in mean disease activity level across racial/ethnic groups, with African-Americans being less likely to achieve clinical remission and having higher disease activity overall (20).

Finally, the working group considered existing analogous measures. The PQRS program has included a measure recommending that RA disease activity be assessed once per year. This measure had several limitations, including that no specific instruments were recommended, there was no requirement to record an actual outcome score (making it difficult to evaluate for improvement or provide benchmarking), and the measure only required assessment once per year, which may not adequately capture the clinical course of a patient with a chronic disease. The working group recommended that the newly proposed measure replace the older PQRS measure concept.

2. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Functional Status

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are of strong interest nationally and are meant to capture the patient’s perspective in a structured way. Among chronic conditions, RA has robust scientific evidence around the validity of functional status PROs. Functional status assessments have been important outcome measures in RA clinical trials and studies, are responsive to therapy changes, and are strong predictors of future disability and mortality (21). Measuring physical function is recommended in RA guidelines because it is a key factor in assessing prognosis and therefore the choice of DMARDs, and because assessment at regular intervals helps determine if a key treatment goal – maintaining functional capacity – is being achieved (6, 22–24). Both U.S. and international groups therefore recommend that provider treatment decisions take functional status into consideration (6, 11, 23).

Although there is strong evidence supporting the importance of functional status as a health outcome in RA, few studies have examined the impact of PRO implementation on health outcomes. However, there is some published experience in implementing PROs in RA, including the Swedish national register, large U.S. health systems such as Geisinger and in many practice settings (17, 25, 26). In addition, studies have demonstrated that functional status assessments impact therapy decisions. For example, in a German study of 1,467 individuals with RA who had undergone a treatment change or started a DMARD, after disease activity assessment using the DAS, functional status assessment had the highest influence on therapy decisions (27).

The working group recommended that the functional status quality measure require use of a validated tool. Members of the working group reviewed the scientific literature on available measures. In addition, a survey was created and administered to experts in RA functional status assessment (see Appendix). Measures that had high quality evidence supporting their psychometric properties and were deemed by experts to be feasible for use in clinical practice were recommended. Feasibility assessment took into account time to administer the PRO, time to score the questions, availability in multiple languages, suitability for lower health literacy populations, and whether there were examples of successful use of the measures in clinical practice. Measures selected included the Multidimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ), Health Assessment Questionnaire II (HAQ-II), Patient-reported Outcomes Measurement System Physical Function instruments (PROMIS-PF10, PROMIS-PF20, PROMIS-PF CAT) (21, 28–31); older legacy measures such as the original Health Assessment Questionnaire and Short Form 36 were less preferable because of weaker psychometric properties, length (HAQ, SF-36) and licensing regulations (SF-36). The working group also recommended that scientific advances in patient-reported outcome measures be incorporated into future iterations of this measure.

The working group considered whether there was opportunity for improvement for this measure. Although population-wide data are lacking, data reported through the ACR’s Rheumatology Clinical Registry show that performance on a related measure (recording of functional status once per year using any method, including narrative assessment) was 69.6% in 2011, improving to 86.6% in 2012. This older PQRS measure has several limitations, including that no specific instruments to assess functional status were recommended and there was no requirement to record an actual outcome score (making it difficult to evaluate for improvement or provide benchmarking). The working group recommended that the newly proposed measure replace the older PQRS measure concept.

3. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug Therapy

Use of DMARDs in every patient with active RA at the earliest stage of disease, ideally within 3 months of disease onset, is recommended in guidelines (6, 23). These guidelines are based on results from numerous clinical trials demonstrating that DMARDs slow the progression of RA by decreasing inflammation and reducing articular erosions. In addition, both clinical trials and observational studies demonstrate that DMARDs improve functional status and health-related quality of life (32). The working group recommended that the measure include a continuously updated list of all available DMARDs that demonstrate efficacy for inflammatory arthritis in clinical trials.

The working group also considered exclusions. Since 2005, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) has maintained a DMARD quality measure that relies on billing data and is used for health plan quality reporting. This measure excludes individuals with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and pregnant women. These exclusions are justified since there is inadequate evidence regarding the use of most DMARDs in HIV and since many DMARDs are either frankly teratogenic (e.g. methotrexate, leflunomide) or have not been adequately studied in pregnant women (33). The working group also recommended adding an exclusion for inactive RA (as indicated by coding “Diagnosis, Inactive: Rheumatoid Arthritis”) based on feedback from rheumatologists on the NCQA measure over the past decade. This exclusion was felt to be clinically justified since some studies suggest that up to 9–15% of individuals with RA may achieve a drug-free remission over the course of their disease (34).

The working group considered whether there was currently opportunity for improvement for this measure. Several studies suggest significant variation in DMARD use among individuals with RA (35). For example, research using the DMARD measure in billing data has found relatively large difference in use based on age, with older individuals being less likely to receive DMARDs. African-Americans, those with low personal incomes, and those residing in zip codes with low socioeconomic status also have significantly lower DMARD use (3, 36). DMARD use is higher for patients seeing rheumatologists, with recent estimates from the RCR showing 96.8%; however, no studies have found a 100% DMARD use rate, as there may reasonable clinical exceptions in practice. Although performance on this measure is expected to be high among rheumatologists, previous studies showing potential disparities in care justified the need for continued use of this measure.

4. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Tuberculosis screening

Latent tuberculosis (TB) infection affects an estimated 9.6 to 14.9 million people in the United States (37). Biologic DMARDs increase the risk of reactivation of latent tuberculosis (TB) infection. TNF–α plays an important role in host responses to myocbacteria, and TNF–α inhibitors are therefore associated with a higher risk of TB infection. Similar associations have been discovered with other biologic DMARDs used in RA, with the possible exception of B-cell depleting agents such as rituximab.

No trials have examined the effectiveness of different screening strategies for TB prior to initiation of biologic DMARDs. Instead, data on TB risk and screening is observational and has accumulated from clinical trials, post-marketing surveillance, and large registries. Early randomized clinical trials of TNF–α inhibitors performed before TB screening became standard of care demonstrated a four-fold higher risk of TB infection (38, 39).. Based on this evidence, the ACR, Centers for Disease Control and international guidelines recommend testing patients for latent TB prior to initiating biologic DMARDs regardless of presence of risk factors (6, 23, 40). Biologic DMARD therapy is contraindicated in those with either active or latent TB until appropriate antimicrobial therapy is started (6).

Consistent with ACR and CDC guidelines, the working group recommended that the eCQM capture screening for TB with either a tuberculin skin test or an interferon-release assay. In addition, we considered the scenario in which patients were treated for latent or active tuberculosis in the past. These patients have persistently positive TB screening tests and re-testing will not add new information. For this population, the working group recommended that the eCQM include evidence of prior treatment as satisfying the numerator.

In devising the denominator population for the measure, the working group recognized that identifying prior TB screening in prevalent biologic DMARD users would be difficult. Challenges include that such screening might have been documented in paper records prior to the transition to EHRs or may be documented in a different prescribing physician’s records. For these reasons, the working group recommended that the measure examine incident users of all biologic DMARDs (except rituximab, where no safety signal has been found), since the current prescriber of the biologic DMARD could reasonably be held accountable for documenting TB screening and treatment in the EHR at the time of prescription. An incident user was defined as a patient with no prescription for a biologic DMARD in the year preceding the measurement year.

The working group also considered whether there was currently opportunity for improvement for this measure. Although population-based studies in the United States are not available, data from the PQRS program found that performance on the TB screening measure was 73.6% in 2011, rising to 92.9% in 2012 and 90.5% in 2013.

Interdisciplinary consensus ratings and electronic specification

The measure concepts and data reviewed above were presented to an interdisciplinary consensus panel, and slight revisions were made. For example, we clarified that attribution of all measures was to the rheumatologist (rather than other health care providers). Ratings on the revised measure concepts are provided in Table 2. Median scores for validity were high (8 or 9). Panel members rated the measures as potentially feasible, with median ratings between 7 and 8.5. Disagreement, as assessed by the number of raters with validity scores ≤ 3 was low or not present. Public comment and review by the ACR Quality of Care Committee and Board of Directors resulted in only recommendations to improve clarity but not change content. The approved measures were then converted to electronic measure format using the Measure Authoring Tool and Quality Data Model, as detailed extensively elsewhere (5).

Table 2.

Data from the American College of Rheumatology’s Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality Measures Project Expert Panel Rating Process for face validity and feasibility, by measure.1,2

| Measures | Median score for validity | Median score for feasibility | # of raters with validity score ≤ 3 | # of raters with validity score ≥ 7 | # of raters total | % of raters with score ≤ 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Disease Activity | 9 | 7 | 1 | 11 | 14 | 7.14% |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) Therapy | 9 | 8 | 1 | 13 | 14 | 7.14% |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Functional Status Assessment | 8 | 8 | 1 | 11 | 14 | 7.14% |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Tuberculosis screening | 9 | 8.5 | 0 | 14 | 14 | 0% |

- Is there adequate scientific evidence or professional consensus to support the indicator?

- Are there identifiable health benefits to patients who receive care specified by the indicator?

- Based on your professional experience, would you consider providers with significantly higher rates of adherence to the indicator higher quality providers?

- Are the majority of factors that determine adherence to the indicator under the control of the physician or health care system?”

Measure scale definitions: For validity, 1=definitely NOT valid to 9=definitely valid; for feasibility, 1=definitely NOT feasible; 9=definitely feasible.

eCQM field-testing

Characteristics of sites where testing was performed are listed in the Appendix. Below we summarize the key findings of field-testing for each eCQM.

1. Feasibility assessment

Quantitative results of the feasibility assessment are included in the Appendix. In general, sites rated current feasibility of the three data elements between 2 and 3 (with 3 indicating that the information is from the most authoritative source when it enters the EHR and is highly likely to be correct; 2 indicating that the information only has a moderate likelihood of being correct and 1 indicating that the data is not accurately captured in the EHR). For both Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Disease Activity and Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Functional Status, some practices had fully operationalized workflows to enter assessments such as Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3) scores into their EHR systems, while others had not.

Concurrent validity assessment

Results for concurrent validity of the numerator of the eCQM are outlined in Table 4. As shown in the Table, there was variability between sites in our statistical measure of agreement (kappa), as well as in sensitivity and specificity.

Table 4.

Performance measure score concurrent validity for numerators of RA electronic clinical quality measures.

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Overall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N K |

Sensitivity | Specificity | N K |

Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | N K |

Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | N K |

Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | |

| Assessment of Disease Activity | 70 1.00 |

100 | 100 | 34 0.17 |

44 (25, 66) | 86 (42, 100) | 117 0.98 |

99 (92, 100) | 100 (92, 100) | 221 .84 |

88 (82, 93) | 99 (94, 100) |

| Functional Status Assessment | 81 1.00 |

100 | 100 | 34 NA |

3 (0.1, 15) | Undef. | 117 0.73 |

96.4 (91, 99) | 100.0 (54, 100) | 232 0.54 |

80.4 (74, 86) | 100 (89, 100) |

| DMARD Therapy | 81 1.00 |

100 | 100 | 34 NA |

94 (80, 99) | Undef. | 58 NA |

98 (91, 100) | Undef | 173 0.85 |

98 (95, 100) | 100 (66, 100) |

| Tuberculosis screening | 62 1.00 |

100 | 100 | 35 0.85 |

93 (76, 99) | 100 (63,100) | 36 0.33 |

69 (50, 84) | 100 (40, 100) | 133 0.73 |

89 (82, 94) | 100 (84, 100) |

K=kappa, a measure of agreement (in these analyses, Kappa=1.0 when the automated EHR data query agrees exactly with data obtained through manual chart extraction, and Kappa=0 when the agreement appears entirely due to chance); RA = rheumatoid arthritis; DMARD = disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug.

Site 1 had perfect agreement on all measures.

2nd site was different for TB screening. 3rd site was different for DMARD therapy and TB screening.

Some Kappas were undefined because there were no true negatives; this is an inherent limitation of the kappa statistic that requires a distribution to produce a result. Similarly, specificity was undefined in instances where the denominator of the specificity calculation (false positive + true negative) was zero.

Site 1 had an advanced EHR with well-established workflows to capture information on RA quality measures. Data elements for RA quality measures at this site were refined and tested over many years, leading to perfect agreement (kappa=1.0, 95%CI 1.0–1.0) as well as a sensitivity and specificity of 100% on all measures. There was more variability at other sites. For example, while all sites were able to demonstrate good sensitivity and specificity for capturing DMARD use among patients with RA (sensitivity 98%, specificity 100% across sites), one site did not routinely capture disease activity or functional status in a structured EHR field, leading to lower sensitivity and specificity (44% and 86%, respectively for disease activity and 3% and undefined, respectively for functional status). Similarly, for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Tuberculosis Screening, sensitivity was reduced (69%) at a site serving a high-risk population in which many patients were previously treated for latent tuberculosis. Information about prior latent TB treatment was available in the text of clinical notes, but did not appear elsewhere in a structured format.

We also assessed validity for the denominator of each measure. There was excellent agreement across all measures. For example, in 221 out of 223 individuals tested across 3 sites for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Disease Activity and Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Functional Status had agreement between the automated extract and the chart review defining RA (99% accuracy). In the discordant cases, patients met the denominator definition for inclusion in the eCQM (including ≥18 years, 2 face-to-face encounters during the measurement year for RA) but did not have RA. This discrepancy resulted from the clinician incorrectly coding the patient’s diagnosis as RA when they had a related condition with inflammatory arthritis (e.g. mixed connective tissue disease).

Similarly, agreement was excellent for the Rheumatoid Arthritis: Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) Therapy (173 out of 175 patients accurately identified; 99% accuracy). Agreement was slightly lower for the denominator component of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Tuberculosis screening (133 out of 147 patients; accuracy 90%) because of instances where the patient was not a new biologic DMARD user; medication reconciliation was incomplete in these cases.

Submission for national endorsement

Measures were submitted to the National Quality Forum in March 2014 for endorsement. An interdisciplinary panel of 21 national experts, the Musculoskeletal Standing Committee, convened to review the measures. This was followed by public and member comment through requests sent to NQF members and through the NQF website. Finally, the measures were examined by the NQF Consensus Standards Approval Committee and Board of Directors, who voted to either fully or conditionally approve the RA measures for endorsement. The full report that includes all of these ratings and deliberations can be found at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2015/01/NQF-Endorsed_Measures_for_Musculoskeletal_Conditions.aspx

Implementation in RISE

The RA eCQMs were implemented in the ACR’s national EHR-enabled registry, RISE. RISE passively collects data from practices, analyzes data centrally to allow benchmarking and can be used for national quality reporting programs. Using an iterative data mapping process, the RISE data team worked with individual practices to make sure data elements in each eCQM were adequately captured. For two RA eCQMs, Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Disease Activity and Rheumatoid Arthritis: Functional Status Assessment, information to satisfy the numerator (disease activity score and functional status score) was not available in a structured data field for some practices, and the team developed text-mining algorithms to capture these scores from clinical notes in the EHR. Work is ongoing to refine eCQM extraction using this methodology.

Discussion

Using a multi-faceted approach that relied on scientific evidence, interdisciplinary stakeholder involvement, and electronic specification and testing of measures in different EHR systems, the ACR has developed eCQMs for RA. The 4 eCQMs cover assessment of key outcomes (disease activity and functional status), treatment (DMARD use), and patient safety (TB screening prior to biological drugs). The measures build on the foundation of quality measurement in RA over the last decade, while incorporating newer data standards such as the Quality Data Model and testing in EHRs to create a set of measures designed for rapid cycle quality improvement. The measures have now been implemented nationwide in the ACR’s EHR-based registry, RISE.

Although the development of eCQMs holds significant promise in leveraging the rich resource of EHR data, we anticipate that methods for refinement and further testing of such measures will continue to evolve. Significant methodological advances in the last several years include development of the QDM, an Office of the National Coordinator-sponsored standard for representing clinical concepts for the Meaningful Use program. The QDM has created a standard for constructing quality measures. For example, in the QDM, clinical data are represented as a set of codes from a standardized terminology system, such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), the Logical Observation of Names and Codes (LOINC), or the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED). However, as illustrated in our project, execution of these QDM-based algorithms still requires mapping at individual sites to ensure that both measure data elements and logic are captured appropriately.

Testing of eCQMs at several clinical sites allowed us to analyze the feasibility and validity of EHR implementation before scaling efforts to the national registry. Several types of challenges were identified during the course of testing. First, two of the measures, Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Disease Activity and Rheumatoid Arthritis: Functional Status Assessment, required extracting an outcome measurement score from the EHR. Because these outcomes were not captured in the Quality Data Model, the ACR submitted the measures to the Value Set Authority Center for inclusion. Next, for practices that record this information in a structured field in the EHR, mapping to identify that data required customization at each site. However, as demonstrated in our testing, some practices had not yet transitioned to collecting this information in a structured field. Using the Quality Data Model and standardized structured data queries would therefore be inadequate for capturing clinical performance in these practices in the near-term. This allowed us to anticipate that implementing eCQMs in RISE would require using procedures such as text mining to capture required data elements. Further work to validate and refine text-mining algorithms is needed, and will likely continue to play a role in capturing eCQM data in the future. EHR vendors can also facilitate eCQMs by providing options for structured and standardized workflows for capture of high priority data elements.

Our work also highlights challenges of eCQM implementation and data extraction. First, the current lack of interoperability between data systems poses significant barriers to accurate data capture. For example, in the safety net hospital testing site, different EHR systems are used for the inpatient and outpatient settings and medication histories prior to the recent outpatient EHR implementation are not available. This created an important data gap for the Rheumatoid Arthritis: Tuberculosis Screening measure. A large number of patients in this setting have latent TB and have been treated appropriately for this condition in the past. However, record of this treatment is not available in the current EHR system and requires manual chart review of older clinical data. eCQM performance therefore looks falsely low and would require implementation of a new and targeted data collection strategy to improve. Similarly, the TB screening eCQM required identification of incident users of biologic medications. Incomplete or inaccurate medication reconciliation also posed challenges for this measure. Examples include incomplete capture of infusible biologic medications, which are not e-prescribed, or difficulties ascertaining incident biologic users because of out-of-date medication information.

We see the methods described here as foundational and expect that both our eCQM specifications and methods to extract data from EHRs will continue to evolve. For example, as new drugs become available, our eCQMs will be continually updated and applied to RISE. In addition, we anticipate that improvements in EHR standardization and interoperability over time will lead to increasingly accurate data capture. However, in the near-term, working with practices to map individual data elements and using methods such as text mining and natural language processing will likely be required to paint an accurate picture of clinical quality in rheumatology practices. Finally, as more rheumatologists create workflows to capture RA outcomes in clinical practice, measurement and benchmarking of patient outcomes to facilitate quality improvement and population management strategies will become possible.

This effort to develop the first set of eCQMs in rheumatology has limitations, many of which are inherent to a new and developing field. First, although we tested our eCQMs in commonly used EHR systems to understand their feasibility and validity, the results presented here are not representative of all EHR systems in the United States. Our testing occurred largely in health systems that had the information technology support to build the eCQMs locally. Second, some of the clinical sites have established workflows to not only collect, but also report, performance on RA quality measures. Data quality and performance at these sites likely exceeds that of many rheumatology clinics. Finally, many questions remain about the feasibility and validity of widespread eCQM implementation in clinical practice, and rheumatology is among the first specialties to embark on a national EHR-enabled registry to collect such measures. RISE is already mapping to over 30 different EHR products, with customization and mapping at each individual clinical site to ensure data accuracy. Currently, data on over 90,000 individuals with RA is being collected in the registry. These experiences with eCQM deployment will influence future iterations of the measures and their implementation.

In conclusion, we used a multifaceted process to build eCQMs in RA. We found that a diverse group of stakeholders, including rheumatologists, patients, and national organizations rated the content of RA measures as important and valid measures of quality. Testing revealed that eCQM deployment is feasible in most practices, but that the lack of standardization of data elements in current EHRs necessitates local mapping and customization to ensure that data is accurate. These initial results in developing and testing RA eCQMs have laid an important foundation for using EHRs as a resource for quality improvement in rheumatology.

SIGNIFICANCE.

Electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs) are a new type of quality measure that rely on automated extraction of clinical information from the electronic health record (EHR).

Using a multifaceted process involving expert consensus, electronic specification and testing for feasibility and validity, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has developed four eCQMs for rheumatoid arthritis.

The rheumatoid arthritis eCQMs have achieved national endorsement and are implemented in the ACR’s national registry, the Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American College of Rheumatology. Dr. Yazdany is also supported by the Robert L. Kroc Chair in Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases (I), AHRQ R01 HS024412 and the Russell/Engleman Medical Research Center for Arthritis. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Disclosures: JY has received an independent research grant from Pfizer. MG has received funds from Abbvie, Amgen, Astellas, Celgene, Gilead, Galapagos, Lilly, Sanofi, Vertex, UCB, Johnson and Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Roche. JAS has received research grants from Takeda and Savient and consultant fees from Savient, Takeda, Regeneron, Iroko, Merz, Bioiberica, Crealta and Allergan pharmaceuticals. JAS serves as the principal investigator for an investigator-initiated study funded by Horizon pharmaceuticals through a grant to DINORA, Inc., a 501c3 entity.

Appendix

Exhibit 1. Members of the American College of Rheumatology’s Expert Panel for the development of quality measures for rheumatoid arthritis

-

Jinoos Yazdany, MD, MPH (presenter, non-voting)

Employer: University of California, San Francisco

City/State: San Francisco, CA

-

Liron Caplan, MD, PhD (Moderator and Expert Panel member)

Employer: Univ of Colorado Denver

City/State: Denver, CO

-

Fiona Donald, MD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Health Plan of San Mateo

City/State: San Mateo, CA

-

Cathleen Colon-Emeric, MD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Duke University

City/State: Durham, NC

-

Daniel Furst, MD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: University of California, Los Angeles

City/State: Los Angeles, CA

-

David Jevsevar, MD, MBA (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Dixie Regional Medical Center

City/State: St. George, UT

-

Shelly Kafka, MD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: University of California, Los Angeles

City/State: Los Angeles, CA

-

Patricia P. Katz, PhD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: University of CA San Francisco

City/State: San Francisco, CA

-

Amye Leong (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Healthy Motivation

City/State: San Francisco, CA

-

Amy Mudano, MPH (Expert Panel member)

Employer: University of Alabama at Birmingham

City/State: Birmingham, AL

-

Eric Matteson, MD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Mayo Clinic

City/State: Rochester, MN

-

Matthew Reimert, MD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Palo Alto Medical Foundation

City/State: Palo Alto, CA

-

Laura Tarter, MD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Stanford University

City/State: Stanford, CA

-

Ralph Webb, MD, FACP (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Marshall University

City/State: Huntington, WV

-

Michael Weinblatt, MD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Brigham & Womens Hospital

City/State: Boston, MA

Email: mweinblatt@partners.org

Role: Development Expert Panel

-

Robert Yood, MD (Expert Panel member)

Employer: Reliant Medical Group

City/State: Worcester, MA

Exhibit 2. Medical informatics specialist who performed electronic specifications of rheumatoid arthritis measures

-

Geraldine Wade MD, MS

Clinical Informatics Consulting

Board Certified in Clinical Informatics

Exhibit 3. Functional status patient-reported outcome experts surveyed for the Rheumatoid Arthritis: Functional Status Assessment quality measure

-

Patricia P. Katz, PhD

Professor of Medicine

University of California, San Francisco

-

James F. Fries, MD

Professor Emeritus of Medicine

Stanford University

-

Theodore Pincus, MD

Clinical Professor of Medicine

New York University

-

Peter Tugwell, MD

Clinical Professor of Medicine

New York University

Exhibit 4. Measure Authoring Tool electronic specifications for four rheumatoid arthritis quality measures

Disease Activity Measurement for Patients with RA

| eMeasure Title | Disease Activity Measurement for Patients with RA | ||

| eMeasure Identifier (Measure Authoring Tool) | 214 | eMeasure Version number | 0 |

| NQF Number | Not Applicable | GUID | 2731ead9-8437-4fd0-9135-1c71c48b4ef4 |

| Measurement Period | January 1, 20xx through December 31, 20xx | ||

| Measure Steward | American College of Rheumatology | ||

| Measure Developer | American College of Rheumatology | ||

| Endorsed By | None | ||

| Description | If a patient has rheumatoid arthritis, then disease activity using a standardized measurement tool should be assessed at >=50% of encounters for RA. | ||

| Copyright | |||

| Disclaimer | CPT(R) contained in the Measure specifications is copyright 2004–2013 American Medical Association. LOINC(R) copyright 2004–2012 Regenstrief Institute, Inc. This material contains SNOMED Clinical Terms(R) (SNOMED CT[R]) copyright 2004–2012 International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation. ICD-10 copyright 2012 World Health Organization. All Rights Reserved. Due to technical limitations, registered trademarks are indicated by (R) or [R] and unregistered trademarks are indicated by (TM) or [TM]. |

||

| Measure Scoring | Proportion | ||

| Measure Type | Process | ||

| Stratification | None | ||

| Risk Adjustment | None | ||

| Rate Aggregation | None | ||

| Rationale | Target low disease activity or remission. The panel recommends targeting either low disease activity (Table 3) or remission (Table 2) in all patients with early RA (Figure 1; level of evidence C) and established RA (Figure 2; level of evidence C) receiving any DMARD or biologic agent. (2012 guideline, page 631) The goal for each RA patient should be low disease activity or remission. In ideal circumstances, RA remission should be the target of therapy, but in others, low disease activity may be an acceptable target. But for other patients, the decision about what the target should be for each patient is appropriately left to the clinician caring for each RA patient, in the context of patient preferences, comorbidities, and other individual considerations. Therefore, this article does not recommend a specific target for all patients. (2012 RA guideline, page 637) |

||

| Clinical Recommendation Statement | In 2008, the American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA PCPI), the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) collaborated to develop a rheumatoid arthritis (RA) quality measure set for the Physical Quality Reporting System (PQRS), including a measure related to disease activity assessment. The measure assessed whether disease activity was assessed at least once per year and categorized as remission, low, moderate or high. The ACR subsequently developed a national registry platform, the Rheumatology Clinical Registry (RCR), to aid rheumatologists in reporting this PQRS measure. In 2012, performance on the measure was 54% among participating rheumatologists. Feedback from the rheumatology community and experts suggested potential ways to improve the measure (Desai S and Yazdany J. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Dec;63(12):3649–60). The current e-measure builds on the experience of the last 6 years to add specificity and greater validity to disease activity assessment in RA (only validated and feasible measures are listed as acceptable, and the requirement for performing assessments has been increased to ≥50% or more of all RA encounters). These changes more closely align with ACR guidelines for measuring disease activity and “treating to target” in RA (Singh J, Arthritis Care Res. 2012 May;64(5):625–39) and Anderson J, Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 May;64(5):640–7). | ||

| Improvement Notation | Higher score indicates better quality | ||

| Reference | Recommendation 1A in 2012 ACR RA guideline (Singh et al. AC&R, 2012) | ||

| Definition | For purposes of this measure, “Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Measurement Tools” include the following instruments:

|

||

| Guidance | One of the requirements for a patient to be included in the Initial Patient Population is that the patient has a minimum of 2 RA encounters with the same provider, all occurring during the measurement period. If the patient qualifies for the Initial Patient Population, then every encounter for RA should be evaluated to determine whether disease activity using a standardized measurement tool was assessed. The logic represented in this measure will determine if the patient had a disease activity assessment performed at each visit during the measurement period (i.e., Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed). The measure requires all of the eligible encounters to be analyzed in order to determine if the patient’s disease activity was assessed at >=50% of encounters for RA. Once it has been determined if the patient meets >=50% threshold, all patient data across a single physician should be aggregated to determine the performance rate. |

||

| Transmission Format | TBD | ||

| Initial Patient Population | Patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis seen for two or more face-to-face encounters for RA with the same clinician during the measurement period | ||

| Denominator | Equals Initial Patient Population | ||

| Denominator Exclusions | None | ||

| Numerator | # of patients with >=50% of total number of outpatient RA encounters in the measurement year with assessment of disease activity using a standardized measure. | ||

| Numerator Exclusions | Not Applicable | ||

| Denominator Exceptions | None | ||

| Measure Population | Not Applicable | ||

| Measure Observations | Not Applicable | ||

| Supplemental Data Elements | For every patient evaluated by this measure also identify payer, race, ethnicity and sex. | ||

Table 3.

Performance on RA electronic clinical quality measures, as assessed by proportion of a random sample of eligible patients receiving recommended care.

| Overall Performance | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Assessment of Disease Activity | N=190 | N=37 | N=34 | N=119 |

| 53.60% | 89.10% | 38.20% | 59.70% | |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Functional Status Assessment | N=223 | N=70 | N=34 | N=119 |

| 69.10% | 62.80% | 2.90% | 93.20% | |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) Therapy | N=175 | N=81 | N=34 | N=60 |

| 93.10% | 88.90% | 94.10% | 98.30% | |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis: Tuberculosis screening | N=47 | N=66 | N=40 | N=41 |

| 72.80% | 86.40% | 67.50% | 56.10% |

N=random sample of EHR patients meeting denominator for front-end chart review.

Population criteria

-

Initial Patient Population =

-

AND:

AND: “Patient Characteristic Birthdate: birth date” >= 18 year(s) starts before start of “Measurement Period”

-

AND: Count >= 2 of:

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Office Visit (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Outpatient Consultation (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Face-to-Face Interaction (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Nursing Facility Visit (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Care Services in Long-Term Residential Facility (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Home Healthcare Services (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

during “Measurement Period”

-

AND:

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Office Visit (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Outpatient Consultation (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Face-to-Face Interaction (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Nursing Facility Visit (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Care Services in Long-Term Residential Facility (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Home Healthcare Services (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

during “Measurement Period”

-

-

Denominator =

AND: “Initial Patient Population”

-

Denominator Exclusions =

None

-

Numerator =

-

AND: “Risk Category Assessment: Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Measurement Tools (result)” during

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Office Visit”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Outpatient Consultation”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Face-to-Face Interaction”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Nursing Facility Visit”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Care Services in Long-Term Residential Facility”

OR: “Occurrence A of Encounter, Performed: Home Healthcare Services”

-

-

Denominator Exceptions =

None

Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) Therapy for Active Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

| eMeasure Title | Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) Therapy for Active Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | ||

| eMeasure Identifier (Measure Authoring Tool) | 209 | eMeasure Version number | 0 |

| NQF Number | Not Applicable | GUID | f6a81f7e-8d14-44ed-99b0-52a931b0be30 |

| Measurement Period | January 1, 20xx through December 31, 20xx | ||

| Measure Steward | American College of Rheumatology | ||

| Measure Developer | American College of Rheumatology | ||

| Endorsed By | None | ||

| Description | If a patient has active rheumatoid arthritis, then the patient should be treated with a DMARD. | ||

| Copyright | |||

| Disclaimer | CPT(R) contained in the Measure specifications is copyright 2004–2012 American Medical Association. LOINC(R) copyright 2004–2013 Regenstrief Institute, Inc. This material contains SNOMED Clinical Terms(R) (SNOMED CT[R]) copyright 2004–2012 International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation. ICD-10 copyright 2012 World Health Organization. All Rights Reserved. Due to technical limitations, registered trademarks are indicated by (R) or [R] and unregistered trademarks are indicated by (TM) or [TM]. |

||

| Measure Scoring | Proportion | ||

| Measure Type | Process | ||

| Stratification | None | ||

| Risk Adjustment | None | ||

| Rate Aggregation | None | ||

| Rationale | Performance measures related to disease-modifying drugs (DMARDs) are the longest and most widely used rheumatoid arthritis (RA) measures in the U.S. health care system. The first DMARD quality indicator was proposed in 2005–2006 as part of the Arthritis Foundation’s Indicator set for RA (Maclean CH et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Feb;35 (4):211–37), and later incorporated into the American College of Rheumatology’s (ACR) Starter Set of Quality Indicators, which was approved by the ACR in 2006. The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) developed administrative claims-based measure specifications for this indicator, which was incorporated into the Health Effectiveness Data Information System (HEDIS), and also approved by the National Quality Forum (NQF) in 2005. Subsequently, under a contract from CMS, NCQA worked with the ACR and the American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA PCPI) to introduce the DMARD measure into the Physical Quality Reporting System (PQRS). The currently proposed measure extends the last decade of work on the DMARD measure by adding electronic specifications. The ACR has worked with NCQA to ensure that the content of the claims-based and electronically specified measures are harmonized. | ||

| Clinical Recommendation Statement | Early RA (disease duration _6 months). In patients with early RA, the panel recommends the use of DMARD monotherapy both for low disease activity and for moderate or high disease activity with the absence of poor prognostic features (Figure 1; level of evidence A–C) (2012 RA guideline, page 631) Established RA (disease duration _6 months or meeting the 1987 ACR RA classification criteria) Initiating and switching among DMARDs. If after 3 months of DMARD monotherapy (in patients without poor prognostic features), a patient deteriorates from low to moderate/high disease activity, then methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, or leflunomide should be added (rectangle A of Figure 2; level of evidence A and B). If after 3 months of methotrexate or methotrexate/DMARD combination, a patient still has moderate or high disease activity, then add another non-methotrexate DMARD or switch to a different non-methotrexate DMARD (rectangle B of Figure 2; level of evidence B and C). (2012 RA guideline, page 631–632) |

||

| Improvement Notation | Higher score indicates better quality | ||

| Reference | Figure 1 & Recommendation 1 in 2012 ACR RA guideline (Singh et al. AC&R, 2012) | ||

| Definition | DMARD therapy includes:

|

||

| Guidance | |||

| Transmission Format | TBD | ||

| Initial Patient Population | Patient age 18 years and older with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis seen for two or more face-to-face encounters for RA with the same clinician during the measurement period | ||

| Denominator | Equals Initial Patient Population | ||

| Denominator Exclusions | Patients with a diagnosis of HIV or patients who are pregnant or patients with inactive RA | ||

| Numerator | Patient received a DMARD | ||

| Numerator Exclusions | Not Applicable | ||

| Denominator Exceptions | None | ||

| Measure Population | Not Applicable | ||

| Measure Observations | Not Applicable | ||

| Supplemental Data Elements | For every patient evaluated by this measure also identify payer, race, ethnicity and sex. | ||

Population criteria

-

Initial Patient Population =

-

AND:

AND: “Patient Characteristic Birthdate: birth date” >= 18 year(s) starts before start of “Measurement Period”

-

AND: Count >= 2 of:

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Office Visit (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Outpatient Consultation (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Face-to-Face Interaction (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Nursing Facility Visit (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Care Services in Long-Term Residential Facility (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Home Healthcare Services (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

during “Measurement Period”

-

-

Denominator =

AND: “Initial Patient Population”

-

Denominator Exclusions =

-

AND:

-

OR:

AND: “Diagnosis, Active: HIV” starts before or during “Measurement Period”

AND NOT: “Diagnosis, Active: HIV” ends before start of “Measurement Period”

-

OR:

AND: “Diagnosis, Active: Pregnancy” starts before or during “Measurement Period”

AND NOT: “Diagnosis, Active: Pregnancy” ends before start of “Measurement Period”

-

OR:

AND: “Diagnosis, Inactive: Rheumatoid Arthritis” starts before or during “Measurement Period”

AND NOT: “Diagnosis, Inactive: Rheumatoid Arthritis” ends before start of “Measurement Period”

-

-

-

Numerator =

-

AND:

-

OR:

AND: “Medication, Active: Rheumatoid Arthritis DMARD Therapy” starts before or during “Measurement Period”

AND NOT: “Medication, Active: Rheumatoid Arthritis DMARD Therapy” ends before start of “Measurement Period”

-

OR:

AND: “Medication, Order: Rheumatoid Arthritis DMARD Therapy” starts before or during “Measurement Period”

AND NOT: “Medication, Order: Rheumatoid Arthritis DMARD Therapy” ends before start of “Measurement Period”

-

OR:

AND: “Medication, Administered: Rheumatoid Arthritis DMARD Therapy” during “Measurement Period”

-

-

-

Denominator Exceptions =

None

Functional Status Assessment for Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

| eMeasure Title | Functional Status Assessment for Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | ||

| eMeasure Identifier (Measure Authoring Tool) | 212 | eMeasure Version number | 0 |

| NQF Number | Not Applicable | GUID | 75e655ca-0a2a-41cd-a5ce-b1f2a3af13e0 |

| Measurement Period | January 1, 20xx through December 31, 20xx | ||

| Measure Steward | American College of Rheumatology | ||

| Measure Developer | American College of Rheumatology | ||

| Endorsed By | None | ||

| Description | IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis, THEN functional status should be assessed using a standardized measurement tool at least once yearly. | ||

| Copyright | |||

| Disclaimer | CPT(R) contained in the Measure specifications is copyright 2004–2013 American Medical Association. LOINC(R) copyright 2004–2012 Regenstrief Institute, Inc. This material contains SNOMED Clinical Terms(R) (SNOMED CT[R]) copyright 2004–2012 International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation. ICD-10 copyright 2012 World Health Organization. All Rights Reserved. Due to technical limitations, registered trademarks are indicated by (R) or [R] and unregistered trademarks are indicated by (TM) or [TM]. |

||

| Measure Scoring | Proportion | ||

| Measure Type | Process | ||

| Stratification | None | ||

| Risk Adjustment | None | ||

| Rate Aggregation | None | ||

| Rationale | In 2008, the American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA PCPI), the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) collaborated to develop a rheumatoid arthritis (RA) quality measure set for the Physical Quality Reporting System (PQRS), including a measure related to functional status assessment. The measure assessed whether functional status was evaluated at least once per year using any method. The ACR developed a national registry platform, the Rheumatology Clinical Registry (RCR), to aid rheumatologists in reporting this PQRS measure. In 2012, performance on the measure was 87% among participating rheumatologists. Over the last six years, feedback from the rheumatology community and experts suggested potential ways to improve the measure (Desai S and Yazdany J. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Dec;63(12):3649–60). The current e-measure builds on the experience of the earlier versions of the measure. It adds specificity to the measure by listing specific tools recommended for valid and reliable functional status assessment in RA. | ||

| Clinical Recommendation Statement | |||

| Improvement Notation | Higher score indicates better quality | ||

| Reference | Requirement for Prognosis Assessment in 2012 ACR RA guideline (Singh et al. AC&R, 2012) | ||

| Definition | Functional status can be assessed by using one of a number of instruments, including several instruments originally developed and validated for screening purposes. Examples include, but are not limited to:

|

||

| Guidance | Use of a standardized tool or instrument to assess functional status other than those listed will meet numerator performance. Other standardized tools used to assess functional status can be mapped to the concept “Intervention, Performed: Rheumatoid Arthritis Functional Status Assessment” included in the numerator logic below. | ||

| Transmission Format | TBD | ||

| Initial Patient Population | Patients age 18 and older with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis seen for two or more face-to-face encounters for RA with the same clinician during the measurement period | ||

| Denominator | Equals Initial Patient Population | ||

| Denominator Exclusions | None | ||

| Numerator | # of patients with functional status assessment documented once during the measurement year. Functional status can be assessed using one of a number of valid and reliable instruments available from the medical literature. | ||

| Numerator Exclusions | Not Applicable | ||

| Denominator Exceptions | None | ||

| Measure Population | Not Applicable | ||

| Measure Observations | Not Applicable | ||

| Supplemental Data Elements | For every patient evaluated by this measure also identify payer, race, ethnicity and sex. | ||

Population criteria

-

Initial Patient Population =

-

AND:

AND: “Patient Characteristic Birthdate: birth date” >= 18 year(s) starts before start of “Measurement Period”

-

AND: Count >= 2 of:

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Office Visit (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Outpatient Consultation (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Face-to-Face Interaction (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Nursing Facility Visit (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Care Services in Long-Term Residential Facility (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

OR: “Encounter, Performed: Home Healthcare Services (reason: ‘Rheumatoid Arthritis’)”

during “Measurement Period”

-

-

Denominator =

AND: “Initial Patient Population”

-

Denominator Exclusions =

None

-

Numerator =

-

AND:

OR: “Intervention, Performed: Rheumatoid Arthritis Functional Status Assessment”

OR: “Functional Status, Result: Rheumatoid Arthritis Functional Status Assessment Tool (result)”

during “Measurement Period”

-

-

Denominator Exceptions =

None

Tuberculosis (TB) Test Prior to First Course Biologic Therapy

| eMeasure Title | Tuberculosis (TB) Test Prior to First Course Biologic Therapy | ||

| eMeasure Identifier (Measure Authoring Tool) | eMeasure Version number | 0 | |

| NQF Number | Not Applicable | GUID | de8ba9e6-8efb-418b-ab30-7703bdf5fb4c |

| Measurement Period | January 1, 20xx through December 31, 20xx | ||

| Measure Steward | American College of Rheumatology | ||

| Measure Developer | American College of Rheumatology | ||

| Endorsed By | None | ||

| Description | If a patient has been newly prescribed a biologic therapy, then the medical record should indicate TB testing in the preceding 12-month period. | ||

| Copyright | Copyright (c) 2013, American College of Rheumatology | ||

| Disclaimer | All materials are subject to copyrights owned by the College. The College hereby provides limited permission for the user to reproduce, retransmit or reprint for such user’s own personal use (and for such personal use only) part or all of any document as long as the copyright notice and permission notice contained in such document or portion thereof is included in such reproduction, retransmission or reprinting. All other reproduction, retransmission, or reprinting of all or part of any document is expressly prohibited, unless the College has expressly granted its prior written consent to so reproduce, retransmit, or reprint the material. All other rights reserved. CPT(R) contained in the Measure specifications is copyright 2004–2013 American Medical Association. LOINC(R) copyright 2004–2012 Regenstrief Institute, Inc. This material contains SNOMED Clinical Terms(R) (SNOMED CT[R]) copyright 2004–2012 International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation. ICD-10 copyright 2012 World Health Organization. All Rights Reserved. Due to technical limitations, registered trademarks are indicated by (R) or [R] and unregistered trademarks are indicated by (TM) or [TM]. |

||

| Measure Scoring | Proportion | ||

| Measure Type | Process | ||

| Stratification | None | ||

| Risk Adjustment | None | ||

| Rate Aggregation | None | ||

| Rationale | In 2008, the American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA PCPI), the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) collaborated to develop a rheumatoid arthritis (RA) quality measure set for the Physical Quality Reporting System (PQRS), including a measure related to TB screening prior to initiation of biologic disease modifying drugs (DMARDs). The current e-measure builds on the experience of the earlier versions of the measure, updating content to align with newer ACR guidelines for RA (Singh J, Arthritis Care Res. 2012 May;64(5):625–39). | ||