Structure of a bacterial adhesin reveals its role in forming a mixed-species symbiotic community with diatoms on sea ice.

Abstract

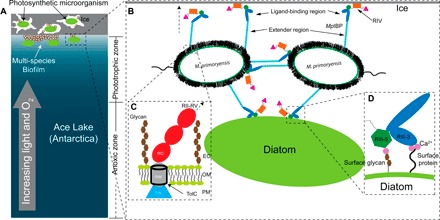

Bacterial adhesins are modular cell-surface proteins that mediate adherence to other cells, surfaces, and ligands. The Antarctic bacterium Marinomonas primoryensis uses a 1.5-MDa adhesin comprising over 130 domains to position it on ice at the top of the water column for better access to oxygen and nutrients. We have reconstructed this 0.6-μm-long adhesin using a “dissect and build” structural biology approach and have established complementary roles for its five distinct regions. Domains in region I (RI) tether the adhesin to the type I secretion machinery in the periplasm of the bacterium and pass it through the outer membrane. RII comprises ~120 identical immunoglobulin-like β-sandwich domains that rigidify on binding Ca2+ to project the adhesion regions RIII and RIV into the medium. RIII contains ligand-binding domains that join diatoms and bacteria together in a mixed-species community on the underside of sea ice where incident light is maximal. RIV is the ice-binding domain, and the terminal RV domain contains several “repeats-in-toxin” motifs and a noncleavable signal sequence that target proteins for export via the type I secretion system. Similar structural architecture is present in the adhesins of many pathogenic bacteria and provides a guide to finding and blocking binding domains to weaken infectivity.

INTRODUCTION

Repeats-in-toxin (RTX) adhesins are a recently discovered class of biofilm-associated proteins (BAPs) needed by many Gram-negative bacteria—such as Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella entrica, and some Pseudomonads—to colonize and infect animal and plant tissues (1–5). At ~2000 residues, RTX adhesins are often the largest proteins produced by their hosts and, based on bioinformatics analyses, share a similar domain organization. They usually contain an N-terminal membrane anchor, an extremely long, repetitive central extender region, and a modular ligand-binding region with C-terminal RTX repeats and a type I secretion system (T1SS) signal.

Despite RTX adhesins’ key role in the tenacity of bacterial biofilms, little is known about their molecular detail. Structural studies on RTX adhesins have been hampered by their massive size and repetitive nature. Consequently, many fundamental questions, such as how RTX adhesins stay attached to the bacterial surface and what are their specific binding partners on various biotic and abiotic substrates, remain to be answered. Here, we have assembled the first overall structure of an RTX adhesin that binds to ice and have deduced the roles for each region or domain of the 1.5-MDa protein, originally called Marinomonas primoryensis antifreeze protein (MpAFP) but now referred to here as M. primoryensis ice-binding protein (MpIBP).

MpIBP was first identified in M. primoryensis isolated from Ace Lake in Antarctica based on its Ca2+-dependent antifreeze activity (6). Once the IBP was isolated by ice-affinity purification, tryptic peptide sequences were derived from it by tandem mass spectrometry and were used to develop a DNA probe to isolate the gene from a genomic library (7). The complete sequence of the protein was derived from the open reading frame in that gene, and its size was seen to be ~100× larger than a typical IBP (8). Bioinformatics analyses suggested that MpIBP might function as an RTX adhesin, with the ability to bind ice, rather than as an AFP, which suppresses the growth of ice. This led us to characterize the adhesin’s sole ice-binding domain, Region IV (RIV), by x-ray crystallography (9) and to examine the perfectly conserved tandem repeats of RII that make up almost 90% of the whole adhesin. We estimated the number of these 104-residue (312 base pairs) repeats to be 120 ± 10 by restriction digests of M. primoryensis DNA analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and Southern blotting. Each repeat folds as a calcium-bound immunoglobulin (Ig)–like β-sandwich domain (10), and four of these in a row behave in solution and in the crystal structure as an extended series with a calcium ion rigidifying the linker region between each domain (11).

To better understand how MpIBP is anchored to the bacterial surface and its role in bacteria-surface adhesion and cell-cell cohesion, we solved the structures of RI, RIII, and RV using a combination of x-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) in this study. The >130 protein domains of MpIBP form a linear chain that gives the adhesin a highly asymmetrical shape, with a calculated length of >600 nm but a width of only 2.5 nm. Approximately 97% of the adhesin structure was solved to high resolution (1 to 2.1 Å). β structure predominates (~55%), and there is a low α-helical content (~5%). Because every domain, except the first and second, binds Ca2+, we estimate that MpIBP coordinates >650 of these ions. This proved advantageous when anomalous diffraction from chelated Ca2+ during x-ray crystallography helped solve several MpIBP domain structures. Moreover, we show here that the ice adhesin is also responsible for binding M. primoryensis to diatoms and for recruiting them to the ice surface to form a symbiotic microcolony in which both bacteria and diatoms benefit from the proximity to each other and to a location that is optimal for photosynthesis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structure of the outer membrane anchor—RI

The ~50-kDa N-terminal RI of MpIBP is the cell surface–anchoring point for the adhesin (Fig. 1). Bioinformatics analyses indicated that RI is similar to the outer membrane (OM)–spanning domains of other BAPs, such as LapA from Pseudomonas fluorescens (4, 12). Hence, RI crosses the bacterium’s OM, with its N-terminal domain (RIN) localized in the periplasmic space and its C-terminal region (RIC) in the extracellular environment, whereas the intervening domain (middle section; RIM) spans the OM (Fig. 2, A to D, and tables S1 and S2). The NMR structure of RIN revealed a novel β-sandwich fold with a triangular cross section (Fig. 2C and table S2). The 30-kDa crystal structure of RIC shows an extended topology (145 Å in length) consisting of three tandem Ca2+-dependent Ig-like domains. The SAXS envelope of the whole RI, comprising five domains in total, is an elongated, kinked rod, whose two ends are in agreement with the RIN and RIC structures (Fig. 2, A, B, E, and F, and table S3). By subtraction, the structure of the ~12-kDa intervening RIM is that of a thin cylinder with a diameter of ~18 Å and a length of ~40 Å (Fig. 2B).

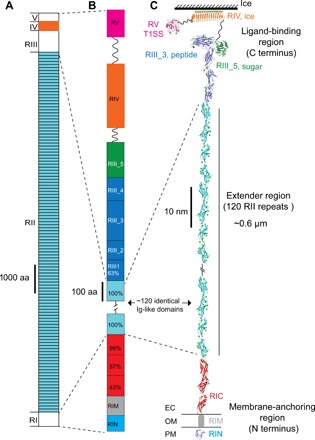

Fig. 1. Overall structure of MpIBP.

(A) Linear domain map of MpIBP drawn to scale. The MpIBP amino acid (aa) sequence is shown in fig. S1. RII and RIV (colored light blue and orange, respectively) are known from two structures solved previously (10, 11, 22). RI, RIII, and RV in white are new three-dimensional structures determined in this study. (B) Expanded view of the RI and RIII to RV linear domain maps colored as in (C). Sequence identities (%) to a 104–amino acid RII repeat are shown for the RIC and RIII_1 domains. (C) NMR and x-ray crystal structures of linked MpIBP domains from N to C termini are shown in cartoon representation: RIN (blue), RIC (red), RII repeats (cyan), RIII_1–4 (dark blue), RIII_5 (dark green), RIV (orange), and RV (magenta). Small green spheres indicate calcium ions. OM is indicated by horizontal lines on either side of RIM. The solution structure of RIM determined by SAXS is illustrated as a gray cylinder. Hatched lines indicate the ~108 RII repeats that are not shown in the figure. The linker regions between RIII_5/RIV (94 residues) and RIV/RV (112 residues) are indicated by wavy lines.

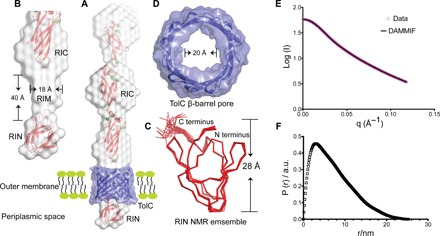

Fig. 2. Detailed structural features of the OM anchoring RI.

(A) The NMR structure of RIN (bottom) and the 2 Å crystal structure of RIC (top) are colored red and fitted into the gray solution structure of the whole RI construct determined by SAXS. The RI solution envelope is fitted through the purple TolC pore homology model embedded in the OM. (B) Close-up view of the cylindrical RIM (gray) determined by SAXS without showing the TolC pore. Dimensions of RIM are indicated. (C) Top-down view of the TolC OM pore model. The internal diameter is indicated. (D) The 20-member NMR structural ensemble of RIN is colored red and shown in ribbon representation. The N and C termini and the height of the protein are marked. (E and F) SAXS data were collected from MpIBP_RI at a concentration of 7 mg/ml. (E) Experimental scattering data of MpIBP_RI (magenta symbols) and fit result of ab initio modeling (DAMMIF, black line). (F) Radial distribution function obtained after Indirect Fourier Transform (IFT) analysis of the scattering data, with data points starting from the first Guinier regime at low q up to the Porod regime at high q values (0.013 Å−1 ≤ q ≤ 0.12 Å−1). a.u., arbitrary units.

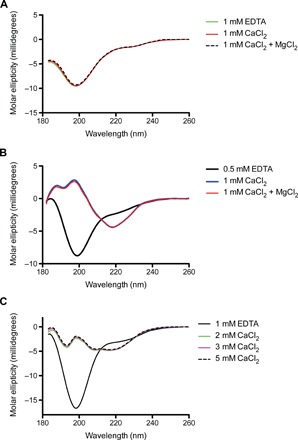

Although RIN and RIC reside on either side of the OM, bioinformatics analysis suggests that RIM does not contain a transmembrane sequence (13). We reason that RIM might interact with an OM protein. RIM’s shape fits snugly into the interior of the conserved T1SS β-barrel pore (TolC) embedded in the OM, which has a predicted internal diameter of 20 Å (Fig. 2D and table S4). The TolC pore restricts passage of folded proteins, and therefore, all T1SS substrates must remain unstructured until they enter the extracellular environment (14), which, for M. primoryensis, is seawater that naturally contains millimolar Ca2+ levels sufficient to fold all the extracellular domains of MpIBP (Fig. 3) (10, 11, 15). When the circular dichroism (CD) spectra of key domains in RI, RIII, and RV (RINM, RIII_5, and RV) were compared in the presence of millimolar Ca2+ and in the absence of these ions (with excess EDTA), only RINM remained unchanged, suggesting that its structure is not dependent on bound Ca2+ (Fig. 3A). However, RIII_5 and RV both underwent marked conformational changes in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 3, B and C). In the absence of Ca2+, both domains were predominantly random coil because their far-ultraviolet (UV) CD spectra contained a single negative peak at ~198 nm. In contrast, the CD spectra of RIII_5 and RV measured in the presence of millimolar Ca2+ showed a positive peak at ~197 nm and a broad negative peak at ~217 nm, which are typical of proteins containing predominantly β-sheet structure. The dependency on millimolar Ca2+ for proper folding observed in RIII_5 and RV has also been seen in RII and RIV (10, 11, 15). The introduction of Mg2+ in addition to Ca2+ did not further change the folding of RINM and RIII_5. While RIM might interact with the interior of TolC, RIN (24 Å × 28 Å × 26 Å) is too large to pass through the pore of TolC, which prevents total release of MpIBP from the cell surface. Because RIN is conserved in many BAPs, this TolC β-barrel plug could generally be used by the adhesins to stay attached to their hosts.

Fig. 3. CD spectra of RINM, RIII_5, and RV measured in EDTA and different concentrations of CaCl2 or MgCl2.

(A) The far-UV CD spectra of RINM were plotted as molar ellipticity versus wavelength. The spectra in the presence of 1 mM EDTA (green line), 1 mM CaCl2 (red line), and both 1 mM CaCl2 and MgCl2 (broken black line) are coincident. (B) The far-UV CD spectra of RIII_5. Spectra in the presence of 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM CaCl2, and both 1 mM CaCl2 and MgCl2 are indicated by black, blue, and red lines, respectively. (C) The far-UV CD spectra of RV. Spectra in the presence of 1 mM EDTA or 2, 3, and 5 mM CaCl2 are indicated by black, green, magenta, and broken black lines, respectively.

The exceptionally long extender—RII

The ~120 ± 10 tandem Ca2+-stabilized Ig-like domains in RII are an extreme amplification of extender modules seen in many surface adhesion proteins from both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (for example, cadherins) (10, 11, 16). We have previously shown that this 0.6-μm-long arm of identical 104-residue repeats is encoded by a genomic sequence of >37 kb (7). Highly repetitive internal DNA sequences encoding large adhesins are often not properly assembled and annotated in the present rapid accumulation of bacterial genomes, and they frequently appear as two separate segments. Despite sequencing the M. primoryensis genome (GenBank accession number CP016181) by the optimal technique for obtaining long sequence reads (Pacific Biosciences), we were unable to link the two ends of the MpIBP ice adhesin gene (17). Thus, the size and abundance of RTX adhesins are significantly larger than they appear in the database (2, 18). A long extender region in an adhesin translates into a long reach to its substrate.

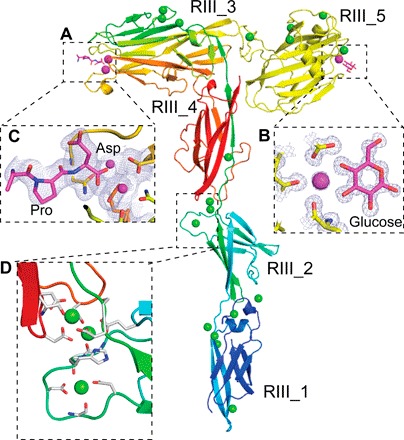

Structures of the various ligand-binding domains in RIII

C-terminal to the RII extender region is a set of ligand-binding domains followed by the T1SS signal. The five β-sandwich domains of RIII form an overall Y shape (Fig. 4, A to D). Three domains (RIII_1, RIII_2, and RIII_4; Fig. 4D) form a Ca2+-stabilized stalk that provides structural support for the ligand-binding RIII_3 and RIII_5 at the branches. RIII_5 is a carbohydrate-binding PA14 domain commonly found in yeast and bacteria (19). Its 1 Å crystal structure, which is reported here, is the first PA14 structure solved from a bacterial adhesin. RIII_5 has a globular β-sandwich fold that uses a coordinated Ca2+ to bind sugar moieties, such as glucose (Fig. 4B). PA14 domains found in yeast adhesins help their hosts flocculate by binding carbohydrates present on neighboring cell surfaces (20). We envisage that MpIBP_RIII_5 has a similar cohesion role to help M. primoryensis form microcolonies by binding bacterial surface carbohydrates, such as lipopolysaccharides.

Fig. 4. Detailed structural features of the MpIBP_RIII ligand-binding domains.

(A) RIII_1–4 is colored in rainbow representation, whereas the RIII_5 construct is colored yellow. Calcium ions in the ligand-binding sites are shown as magenta spheres, whereas the other Ca2+ are shown as green spheres. (B) Enlarged view of the sugar-binding site of the RIII_5 structure, showing the 1 Å 2Fo − Fc map and the carbon atoms of the glucose molecule colored magenta. Oxygen atoms are red, and nitrogen atoms are blue. (C) Enlarged view of the ligand-binding cavity of RIII_3 is shown with the 2.1 Å resolution 2Fo − Fc map contoured at 1 σ [as in (B)]. Ca2+ coordination by the C-terminal Pro and Asp residues from a symmetry-related molecule are shown in stick representations. (D) Enlarged view of the Ca2+-stiffened linker region between RIII_2 and RIII_4. Ca2+ coordinating residues are shown in stick representation.

In the ligand-binding domain RIII_3 on the opposite branch from RIII_5, two Ca2+ ions sit side by side in a cavity at the outer tip of the oblong β-sandwich (Fig. 4A). Similar to the sugar-binding site of RIII_5, this positively charged pocket of RIII_3 is exposed to solvent and accessible to ligands. The C-terminal “Pro-Asp” residues from a symmetry-related molecule in the crystal are stably bound in this pocket (Fig. 4C). Thus, we consider RIII_3 to be a peptide/protein-binding domain. RIII_3 is the initial structure solved of this domain type, but a similar sequence is present in an epithelial cell–binding RTX adhesin from V. cholerae, which promotes host colonization within the intestine (1, 2). RIII_3 and the sugar-binding RIII_5 might facilitate the cohesion of their host during biofilm formation. Self-association through these domains could explain why M. primoryensis are slow to dissociate following melting of an ice crystal to which they were bound en masse (21).

RIII_3 and RIII_5 bind M. primoryensis to diatoms

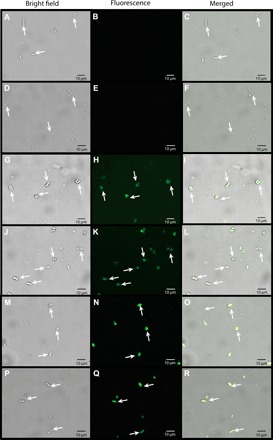

Diatoms and algae are typically concentrated underneath the ice cover, where they gain optimal access to light needed for photosynthesis (22–24). We considered that RIII_3 and RIII_5 could tether M. primoryensis to extracellular polysaccharides and proteins on photosynthetic microorganisms and facilitate their binding to ice. When we mixed two different Antarctic diatoms (Chaetoceros neogracile and Fragilariopsis cylindrus) with M. primoryensis, the bacteria avidly bound to C. neogracile to form cell clusters (Fig. 5, A to C, movies S1 and S2) and were able to secure the diatoms to ice (Fig. 5, F to H). C. neogracile alone show no affinity for ice (Fig. 5D); however, M. primoryensis homed in on these diatoms, bound to them (Fig. 5E and movie S1), and were able to move them through the medium to both bind them to ice (Fig. 5, F to H, and movie S3) and resist displacement by fluid flow (movie S4). Consistent with our hypothesis that RIII might link bacteria to diatoms, a fluorescently labeled recombinant version of this region of MpIBP bound selectively to the surface of C. neogracile but not to that of F. cylindrus (Fig. 5, I to Q). Both the peptide-binding RIII_3 and the sugar-binding RIII_5 are responsible for this bacteria-diatom interaction (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. M. primoryensis selectively binds the diatom C. neogracile.

SEM images of (A) single or (B) multiple C. neogracile (indicated by white arrows) bound by M. primoryensis (indicated by yellow arrows). Representative bright-field microscopy images of C. neogracile (marked by white arrows) in the presence of (C) M. primoryensis (yellow arrows) or (D) ice. Bright-field microscopy images of M. primoryensis + C. neogracile microcolonies with (F, G, and H) or without (E) ice. Light (I, L, and O) and fluorescence microscopy images (J, M, and P) of a mixture of diatoms, C. neogracile (white arrows), and F. cylindrus (green arrows), incubated with TRITC-labeled RIII_1–5. Slight shifts in the merged images (K, N, and Q) between the fluorescence and bright-field images are due to drifting of the cells between image capture.

Fig. 6. RIII_5 sugar-binding and RIII_3 peptide-binding domains are responsible for binding to C. neogracile.

Light (A, D, G, J, M, and P), fluorescence (B, E, H, K, N, and Q), and merged (C, F, I, L, O, and R) images of diatom C. neogracile (white arrows) incubated with green fluorescent protein–tagged MpIBP domains: RII (A to F), RIII_5 (G to L), and RIII_3 (M to R). All images were captured with the same length of exposure.

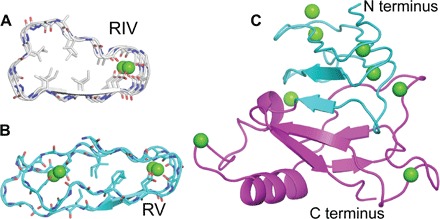

Structure of RIV and RV: RTX repeats and T1SS sequence

RIV is the only MpIBP domain that can bind ice. Previous work showed that RIV is an atypical RTX β-roll that binds internal Ca2+ ions down only one side of the protein (Fig. 7A) (9). The ice-binding surface of RIV is a flat, repetitive array of outward-projecting Thr and Asx residues that organize surface waters into an ice-like pattern. These “anchored clathrate waters” match and “freeze” MpIBP to several planes of ice, providing MpIBP with a third, and most distinctive, adhesion capability. Members of the Marinomonas genus are spread worldwide, with many of the species isolated from temperate regions (25, 26). Therefore, most have no biological need for an ice-binding adhesin. According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information database, there are currently genome sequences for 17 Marinomonas species, in addition to the M. primoryensis genome presented here. A simple BLASTp search reveals that none of these genomes contain the widespread DUF3494 IBP, found in many other microorganisms (27). However, all of the genomes contain a putative adhesin similar to MpIBP. The C-terminal regions of these proteins vary, although all of them end with RTX repeats similar to those found in RV of MpIBP and which give the RTX adhesins their name. Homologs of the sugar-binding RIII_5 found in MpIBP are present in at least seven of the species. However, only one sequence contains a putative RIV-like domain. That sequence was found in Marinomonas ushuaiensis, which was isolated from the southern tip of South America and is the closest of the isolates geographically to M. primoryensis (28). Its adhesin contains a region homologous to the imperfect repeats of RIV. However, although the general nonapeptide repeat is present, the residues needed for ice-binding are missing (15). Therefore, MpIBP is the only member of the Marinomonas genus known to have an IBP. Moreover, we have searched the M. primoryensis genome without finding any other IBP types. Also, in isolating MpIBP, all the ice-binding activity in the bacterium was purified with this one high–molecular weight protein, suggesting that there are no other IBPs present.

Fig. 7. Structural comparison between the RIV and RV of MpIBP.

(A) Cross section of the RTX repeats of RIV (gray). (B) Cross section of the RTX repeats of RV (cyan). (C) The 1.45 Å structure of RV. The N-terminal moiety is colored green, whereas the C-terminal moiety is colored magenta.

RV has two structural components. The N-terminal section has a conventional RTX fold (Fig. 7, B and C), having parallel β-strands with Ca2+ ions inside both turns of the β-roll. Given the proximity of regions IV and V, duplication and divergence of this fold may have given rise to RIV. The second part of RV spans MpIBP’s C-terminal T1SS secretion signal (interpro) (29) and is composed of antiparallel β-strands with an α-helical capping structure (Fig. 7C). As the C-terminal domain of MpIBP, RV is the first to be exported to the Ca2+-rich extracellular environment and may act as a nucleus to initiate proper folding of the entire adhesin (30).

Biofilm symbiosis under the ice

Ace Lake in Antarctica, the geographic source of this isolate of M. primoryensis, is brackish and stratified, with a permanently anoxic region ~12 m below the surface (Fig. 8A) (31). Because of the near permanent ice/snow cover, relatively little light penetrates to the water, mostly to the upper few meters. Thus, it is advantageous for the strictly aerobic M. primoryensis to remain in this phototrophic layer where there is oxygen for respiration and nutrients from living and dead photosynthetic microorganisms. Our structural and functional characterization of the MpIBP adhesin shows that it has both the adhesive and cohesive properties necessary to position M. primoryensis as part of a microbial community on the underside of the ice and in brine channels, with the ability to recruit diatoms into this niche to form a symbiotic relationship (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8. Model of M. primoryensis collectively binding with diatoms to ice.

(A) Ice/snow that covers the surface of Ace Lake to a depth of 1 to 2 m is represented by a gray rectangle with three internal brine channels of irregular shape. Lake water is colored blue with a light to dark gradient from top to bottom signifying the increased availability of light and oxygen toward the top of the water column as indicated by the gray arrow. Bacteria and photosynthetic microorganisms such as diatoms within the brine pits and underneath the ice are drawn as small white ovals and large green ovals, respectively. The phototrophic and anoxic zones are indicated on the right. (B) Expanded view of (A) showing two linked bacterial cells bound to ice and a diatom. Cell-surface proteins and carbohydrates are drawn as fuzzy black hairs, and the polar flagella are drawn as squiggles. MpIBPs protrude from cell surfaces. RII, RIII_1–4, RIII_5, RIV, and RV are drawn as cyan rods, blue ovals, dark green hexagons, orange rectangles, and magenta triangles, respectively. (C) Expanded view of the cell surface–anchoring domains of MpIBP near the OM. OM is drawn the same way as in Fig. 2A. Surface glycans are drawn as connected brown hexagons. RIN, RIM, and RIC are drawn as a blue triangle, a gray cylinder, and red ovals, respectively. The hollow TolC OM pore is outlined in black. The arrow with a broken line indicates the protein continues to RII to RV. (D) Enlarged view of MpIBP_RIII interacting with the peptide and sugar molecules on the cell surface of a diatom. Ligand-binding Ca2+ are drawn as magenta spheres. Surface protein is indicated by a wavy line from the cell surface.

Ice is a dynamic substrate (constantly growing or melting), making it difficult for individual cells to stay attached. The adhesive and cohesive properties of MpIBP are therefore crucial for the bacterium to bind this dynamic surface and remain attached as a community of M. primoryensis that can have a collective grip on ice. Having a specific length to the extender region (RII) enables the neighboring bacteria to simultaneously contact each other through their ligand-binding domains in RIII (Fig. 8, C and D). Similar scenarios likely apply to other bacteria living in harsh conditions, where they require multipurpose adhesins like MpIBP to counter high shear flow, pressure, and other destabilizing forces that might weaken a biofilm.

Conclusions and outlook

This study has revealed the first detailed structure at the molecular level of a bacterial adhesin (MpIBP), along with the function of nearly all its ~130 domains. N-terminal domains in RI of the RTX adhesin are involved in the retention of this giant 1.5-MDa protein in the OM of its marine bacterium. Most of the domains are present in RII, which serves to extend the ligand-binding domains in RIII and RIV away from the host surface. Although it was already known that RIV contained the ice-binding domain, adjacent to it in RIII are sugar- and peptide-binding domains that not only play a role in bacterial cohesion on the ice surface but also selectively bind at least one type of psychrophilic marine diatom. These functions set up a striking example of microorganism symbiosis, whereby the adhesin links bacteria and diatoms together in mixed-species microcolonies on ice. The diatoms benefit from being borne to an optimal zone for photosynthesis in ice-covered marine environments, and the bacteria presumably benefit from the oxygen and waste products made by the diatoms. Before this study, little was known about RTX adhesin-ligand interactions. Reports on surface-adhesin interaction have been limited to probing a small number of generic hydrophobic and hydrophilic materials (for example, polystyrene and glass), although no specific ligand has been identified for cell-cell cohesion (32). Consequently, it has not been possible to develop inhibitors to block adhesin binding and disrupt biofilm formation. The high-resolution protein-ligand complex structures of the MpIBP domains solved here provide a highly promising “first-of-its-kind” guide to the rational design of inhibitors to other bacterial adhesins. We have recently shown that polyclonal antibodies raised to the ice-binding domain of MpIBP can completely block M. primoryensis adsorption to ice (21). Thus, it is likely that RTX adhesins are responsible for initial contacts with bacterial substrates, and this abrogation strategy might be generally applicable. Blocking their ability to adhere and cohere can be a method to treat chronic infections and other unwanted biofilm formation. By the same token, the engineering of adhesins to include new ligand-binding domains could be a method for reinforcing beneficial biofilms (33).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of MpIBP domains

The genes encoding the RIII_1–4, RIII_5, and RV constructs were ligated between the Nde I/Xho I sites of the pET28a expression vector placing an N-terminal 6× His-tag on each protein. The genes encoding RIN and RI of MpIBP were ligated into the Nde I/Xho I sites of the pET24 expression vector again placing a C-terminal 6× His-tag on each protein. For NMR experiments, RIN was expressed in M9 minimal medium containing 13C glucose and 15N NH4Cl as the sole carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively (34). All other proteins were expressed and purified on the basis of previously published protocols (9–11, 15).

Crystallization and x-ray crystal structural solutions of RIC, RIII_1–4, RIII_5, and RV

MpIBP domains were crystallized at room temperature using the microbatch methods as previously described (10, 11). Briefly, RIC was crystallized at 20 mg/ml in a precipitant solution containing 0.1 M MES (pH 6), 0.2 M magnesium chloride, and 20% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 6000. RIII_1–4 was crystallized at 5 mg/ml in a precipitant solution containing 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.6), 0.1 M calcium chloride, and 15% (w/v) PEG400. RIII_5 was crystallized at 15 mg/ml in a precipitant solution containing 0.1 M Hepes (pH 7), 0.2 M calcium chloride, 20% (w/v) PEG6000, and 30% (w/v) d-(+)-glucose monohydrate. RV was crystallized at 15 mg/ml in a solution containing 0.1 M calcium chloride, 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.6), and 30% (v/v) PEG400. High-resolution data sets of RIII_1–4, RIII_5, and RV were collected from the 08ID-1 beamline of the Canadian Light Source synchrotron facilities, whereas the data set of RIC was collected at the X6A beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory).

Data for RIC, RIII_5, RIII_1–4, and RV were indexed and integrated with X-ray Detector Software (XDS) (35) and scaled with CCP4-Aimless (36). The structure of RIC was solved by molecular replacement with CCP4-Phaser (37, 38), using the RII monomer [PDB (Protein Data Bank): 4KDV] structure as the search model. The high-resolution structures of RIII_5, RIII_1–4, and RV were determined by molecular replacement with CCP4-Phaser using their respective low-resolution structures solved by in-house Ca2+ phasing as search models (6). The structures were built using CCP4-Buccaneer and were manually corrected in Coot (39, 40). The structures were refined using CCP4-Refmac5 (41).

NMR spectroscopy and structure calculations

All NMR experiments were performed at 303 K using a Varian INOVA 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance room temperature probe. The RIN sample contained 3 mM 13C/15N labeled RIN in 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 6.5), 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, and 10% D2O. Standard triple-resonance experiments were used to assign the backbone and side chain resonances of RIN. Both aliphatic and aromatic 13C NOESY-HSQC and 15N NOESY-HSQC data sets were collected with 100-ms mixing times to provide distance restraints between nuclei. NMR data were processed using NMRPipe (version 8.1) (42), and spectra were assigned using CcpNmr Analysis version 2.4.2 (43). ARIA 2.3 and CNS version 2.1 were used to generate an ensemble of solvent-refined structures using NOESY peak lists, DANGLE-derived (44) ϕ and ϕ dihedral angle restraints, and hydrogen bond restraints derived from a D2O exchanged sample of RIN.

SAXS data acquisition and reduction of MpIBP_RI

Synchrotron radiation x-ray scattering data on RI was collected at the BM29 BioSAXS beamline of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France) (45) operating at 12.5 keV. The scattering intensity was measured as a function of the momentum transfer vector q = 4π(sinθ)/λ, where λ = 0.992 Å is the radiation wavelength, and 2θ is the scattering angle. The beam size was set at about 700 μm × 700 μm, and two-dimensional scattering profiles were collected using a Pilatus 1M detector. Samples were measured at a fixed sample-to-detector distance of 2.867 m to cover an angular range of 0.03 to 5 nm−1. Samples were loaded via an automated sample changer and flowed through a quartz capillary of 1.8 mm in diameter, while collecting 10 frames of 0.1 s with a reduced flux of 1012 photons s−1. The averaged value of buffer scattering measured before and after the sample measurements was subtracted from the averaged sample scattering curve. Samples were measured at four concentrations (2, 5, 7, and 10 mg ml−1), and the scattering profiles were brought to absolute scale using the known scattering cross section per unit sample volume, dΣ/dΩ, of water and verified using a bovine serum albumin protein standard. Data analysis and molecular shape reconstruction were performed as described previously (11, 46).

Scanning electron microscopy and fluorescence microscopy images

Electron microscopy images were collected using a Hitachi S-3000N scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Queen’s University, Canada). Bacteria and diatom mixtures were prepared for SEM as previously described (47). Briefly, 1 ml of bacterial diatom sample was pelleted by centrifugation. The pellet was dehydrated by gradually increasing the ethanol concentration to 15, 50, and 100%. The pellet was resuspended in 100% ethanol and diluted 10-fold with 100% ethanol. Next, an aliquot (200 μl) of the diluted sample was dried onto an aluminum foil for 10 min at 90°C. The dried samples were cut into approximately 2-cm squares and visualized by SEM. Light and fluorescence microscopy images were taken with an Andor Zyla 4.2 Plus camera paired with an Olympus IX83 inverted fluorescence microscope.

Growth of M. primoryensis and diatoms

M. primoryensis were streaked onto a marine broth plate without antibiotic. A single colony of bacteria was used to inoculate marine broth (10 ml) and cultured at 4°C without shaking for 4 to 5 days until reaching an optical density (OD600nm) of 0.2 to 0.5 in a ThermoFisher Scientific Multiskan Go spectrometer (21). Both F. cylindrus and C. neogracile were grown as previously described (48, 49). Thus, diatoms were grown in F/2 medium at 4°C with light and shaking. Bacteria cultured to an OD600nm of 0.2 to 0.4 were incubated with diatoms overnight at 4°C with light and shaking before being visualized with an Andor Zyla 4.2 Plus camera paired with an Olympus IX83 inverted fluorescence microscope modified with a custom-built cooling stage (50).

Circular dichroism

Aliquots of RINM were dialyzed against 10 mM tris-HCl (pH 9) and 0.1 mM EDTA (buffer 1), 10 mM tris-HCl (pH 9) and 1 mM CaCl2 (buffer 2), or 10 mM tris-HCl (pH 9) and 1 mM CaCl2 + 1 mM MgCl2 (buffer 3). Next, each sample was diluted to a concentration of 35 μM. Scans were taken for each sample at 23°C with a Chirascan CD spectrometer (Applied Photophysics). All scans for each sample were averaged and buffer reference–subtracted, and three-point smoothing was applied to the data with PROVIEWER software. CD for RIII_5 (20 μM) and RV (30 μM) were done using the same procedures as above, with different concentrations of CaCl2 (1 mM for RIII_5 and 2, 3, and 5 mM for RV).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to E. Jin from the Research Institute for Natural Sciences at Hanyang University (Seoul, Korea) for the gift of the two diatom species used in this study. We thank K. Munro from the Protein Function Discovery at Queen’s University for help with acquiring and interpreting CD data. We thank S. Gauthier, Q. Ye, S. Phippen, T. He, and R. Lang for assistance with cloning and crystallization trials. We thank C. Garnham for doing essential groundwork and for guiding S.G. during the early stages of this project. We are grateful to the staff at the 08ID-1 beamline of the Canadian Light Source (Saskatoon, Canada), the X6A beamline in the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory, NY), the G1 station in the Macromolecular Diffraction Facility at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (Ithaca NY), and the BM29 beamline at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facilities (Grenoble, France) for access to the synchrotron facilities and for help with acquiring x-ray crystallographic and SAXS data. Funding: This work was funded by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) discovery grants to S.P.S. (RGPIN 2015-06667), J.S.A. (RGPIN 2013-356025), C.E. (RGPIN 2014-05138), and P.L.D. (RGPIN 2016-04810), by a Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI) grant to C.E., by European Research Council (ERC) grants to I.B. (281595) and I.K.V. (635928), by a Dutch Science Foundation grant (NWO ECHO Grant No.712.016.002) and Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science grant (Gravity Program 024.001.035) to I.K.V., and by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation operating grant to P.L.D. (106612). P.L.D. holds the Canada Research Chair in Protein Engineering. J.S.A. holds a Canada Research Chair in Structural Biology. D.N.L. was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Fellowship. C.A.S. is funded by a Post-Graduate Scholarships - Doctoral Program (PGS-D) NSERC Scholarship. Author contributions: P.L.D. and S.G. conceived the study, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. S.G. performed crystallization, data collection, and structure determination of the x-ray crystal structures. R.L.C. and J.S.A. contributed to the structural interpretation. S.G. and D.N.L. performed NMR data collection and structure determination. S.P.S. contributed to the NMR data interpretation. S.G., L.L.C.O., and I.K.V. performed SAXS data collection and analyses. C.A.S. performed SEM and light/fluorescence microscopy experiments in microfluidic systems. C.A.S., S.R.Y., C.E., M.B.-D., V.Y., and I.B. contributed in designing, manufacturing, and operating the microfluidic devices. T.D.R.V. and L.A.G. performed genome sequencing and bioinformatics analyses. All authors contributed to writing and editing the drafts of the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors. The atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported x-ray crystal structures were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession codes: 5IRB (RIC), 5K8G (RIII_1–4), 5J6Y (RIII_5), and 5JUH (RV). The chemical shifts and the final structural ensemble of RIN were deposited into the Biomagres Bank (30040) and the PDB (5IX9). The genomic sequence of M. primoryensis has been deposited in GenBank (accession number CP016181).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/8/e1701440/DC1

fig. S1. Amino acid sequence of MpAFP.

table S1. Crystallographic statistics for the RIC, RIII_1–4, RIII_5, and RV of MpAFP.

table S2. NMR structural statistics of MpAFP_RIN.

table S3. Parameters obtained from SAXS experiments.

table S4. Statistics of homology modeling studies (Phyre2 Server) on the OM protein TolC of M. primoryensis.

movie S1. M. primoryensis binds to C. neogracile to form a multicellular cluster and moves the mass through the medium.

movie S2. M. primoryensis does not interact with F. cylindrus.

movie S3. M. primoryensis moves the mixed-cell cluster through the medium and secures it to ice (top left corner).

movie S4. The ice-bound cell cluster of M. primoryensis and C. neogracile can resist displacement by fluid flow.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Satchell K. J. F., Structure and function of MARTX toxins and other large repetitive RTX proteins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 71–90 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Syed K. A., Beyhan S., Correa N., Queen J., Liu J., Peng F., Satchell K. J. F., Yildiz F., Klose K. E., The Vibrio cholerae flagellar regulatory hierarchy controls expression of virulence factors. J. Bacteriol. 191, 6555–6570 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner C., Polke M., Gerlach R. G., Linke D., Stierhof Y.-D., Schwarz H., Hensel M., Functional dissection of SiiE, a giant non-fimbrial adhesin of Salmonella enterica. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 1286–1301 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newell P. D., Boyd C. D., Sondermann H., O'Toole G. A., A c-di-GMP effector system controls cell adhesion by inside-out signaling and surface protein cleavage. PLOS Biol. 9, e1000587 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Gil M., Yousef-Coronado F., Espinosa-Urgel M., LapF, the second largest Pseudomonas putida protein, contributes to plant root colonization and determines biofilm architecture. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 549–561 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert J. A., Davies P. L., Laybourn-Parry J., A hyperactive, Ca2+-dependent antifreeze protein in an Antarctic bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245, 67–72 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo S. Q., Garnham C. P., Whitney J. C., Graham L. A., Davies P. L., Re-evaluation of a bacterial antifreeze protein as an adhesin with ice-binding activity. PLOS ONE 7, e48805 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies P. L., Ice-binding proteins: A remarkable diversity of structures for stopping and starting ice growth. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 548–555 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garnham C. P., Campbell R. L., Davies P. L., Anchored clathrate waters bind antifreeze proteins to ice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7363–7367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo S. Q., Garnham C. P., Partha S. K., Campbell R. L., Allingham J. S., Davies P. L., Role of Ca2+ in folding the tandem β-sandwich extender domains of a bacterial ice-binding adhesin. FEBS J. 280, 5919–5932 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vance T. D. R., Olijve L. L. C., Campbell R. L., Voets I. K., Davies P. L., Guo S., Ca2+-stabilized adhesin helps an Antarctic bacterium reach out and bind ice. Biosci. Rep. 34, e00121 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navarro M. V. A. S., Newell P. D., Krasteva P. V., Chatterjee D., Madden D. R., O'Toole G. A., Sondermann H., Structural basis for c-di-GMP-mediated inside-out signaling controlling periplasmic proteolysis. PLOS Biol. 9, e1000588 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., Sonnhammer E. L. L., Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delepelaire P., Type I secretion in Gram-negative bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694, 149–161 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garnham C. P., Gilbert J. A., Hartman C. P., Campbell R. L., Laybourn-Parry J., Davies P. L., A Ca2+-dependent bacterial antifreeze protein domain has a novel β-helical ice-binding fold. Biochem. J. 411, 171–180 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro L., Weis W. I., Structure and biochemistry of cadherins and catenins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a003053 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhoads A., Au K. F., PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 13, 278–289 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou G., Yuan J., Gao H., Regulation of biofilm formation by BpfA, BpfD, and BpfG in Shewanella oneidensis. Front. Microbiol. 6, 790 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigden D. J., Mello L. V., Galperin M. Y., The PA14 domain, a conserved all-β domain in bacterial toxins, enzymes, adhesins and signaling molecules. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 335–339 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veelders M., Brückner S., Ott D., Unverzagt C., Mösch H.-U., Essen L.-O., Structural basis of flocculin-mediated social behavior in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 22511–22516 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bar Dolev M., Bernheim R., Guo S., Davies P. L., Braslavsky I., Putting life on ice: Bacteria that bind to frozen water. J. R. Soc. Interface 13, 20160210 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janech M. G., Krell A., Mock T., Kang J.-S., Raymond J. A., Ice-binding proteins from sea ice diatoms (Bacillariophyceae). J. Phycol. 42, 410–416 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond J. A., Algal ice-binding proteins change the structure of sea ice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E198 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Souza N. A., Kawarasaki Y., Gantz J. D., Lee R. E. Jr, Beall B. F. N., Shtarkman Y. M., Koçer Z. A., Rogers S. O., Wildschutte H., Bullerjahn G. S., McKay R. M. L., Diatom assemblages promote ice formation in large lakes. ISME J. 7, 1632–1640 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solano F., Garcia E., Perez D., Sanchez-Amat A., Isolation and characterization of strain MMB-1 (CECT 4803), a novel melanogenic marine bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 3499–3506 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumari P., Poddar A., Das S. K., Marinomonas fungiae sp. nov., isolated from the coral Fungia echinata from the Andaman Sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64, 487–494 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayer-Giraldi M., Uhlig C., John U., Mock T., Valentin K., Antifreeze proteins in polar sea ice diatoms: Diversity and gene expression in the genus Fragilariopsis. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 1041–1052 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabagaran S. R., Suresh K., Manorama R., Delille D., Shivaji S., Marinomonas ushuaiensis sp. nov., isolated from coastal sea water in Ushuaia, Argentina, sub-Antarctica. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 309–313 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell A., Chang H.-Y., Daugherty L., Fraser M., Hunter S., Lopez R., McAnulla C., McMenamin C., Nuka G., Pesseat S., Sangrador-Vegas A., Scheremetjew M., Rato C., Yong S.-Y., Bateman A., Punta M., Attwood T. K., Sigrist C. J. A., Redaschi N., Rivoire C., Xenarios I., Kahn D., Guyot D., Bork P., Letunic I., Gough J., Oates M., Haft D., Huang H., Natale D. A., Wu C. H., Orengo C., Sillitoe I., Mi H., Thomas P. D., Finn R. D., The InterPro protein families database: The classification resource after 15 years. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D213–D221 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bumba L., Masin J., Macek P., Wald T., Motlova L., Bibova I., Klimova N., Bednarova L., Veverka V., Kachala M., Svergun D. I., Barinka C., Sebo P., Calcium-driven folding of RTX domain β-rolls ratchets translocation of RTX proteins through type I secretion ducts. Mol. Cell 62, 47–62 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laybourn-Parry J., Bell E. M., Ace Lake: Three decades of research on a meromictic, Antarctic lake. Polar Biol. 37, 1685–1699 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd C. D., Smith T. J., El-Kirat-Chatel S., Newell P. D., Dufrêne Y. F., O'Toole G. A., Structural features of the Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilm adhesin LapA required for LapG-dependent cleavage, biofilm formation, and cell surface localization. J. Bacteriol. 196, 2775–2788 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vlamakis H., Chai Y., Beauregard P., Losick R., Kolter R., Sticking together: Building a biofilm the Bacillus subtilis way. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 157–168 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grondin J. M., Chitayat S., Ficko-Blean E., Boraston A. B., Smith S. P., 1H, 15N and 13C backbone and side-chain resonance assignments of a family 32 carbohydrate-binding module from the Clostridium perfringens NagH. Biomol. NMR Assign. 6, 139–142 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabsch W., Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Cryst. 66, 133–144 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans P., Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Cryst. 62, 72–82 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mccoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J., Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G. W., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., Read R. J., Vagin A., Wilson K. S., Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Cryst. 67, 235–242 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowtan K., The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Cryst. 62, 1002–1011 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K., Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst. 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vagin A. A., Steiner R. A., Lebedev A. A., Potterton L., McNicholas S., Long F., Murshudov G. N., REFMAC5 dictionary: Organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Cryst. 60, 2184–2195 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A., Nmrpipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vranken W. F., Boucher W., Stevens T. J., Fogh R. H., Pajon A., Llinas M., Ulrich E. L., Markley J. L., Ionides J., Laue E. D., The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: Development of a software pipeline. Proteins 59, 687–696 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheung M.-S., Maguire M. L., Stevens T. J., Broadhurst R. W., DANGLE: A Bayesian inferential method for predicting protein backbone dihedral angles and secondary structure. J. Magn. Reson. 202, 223–233 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pernot P., Round A., Barrett R., De Maria Antolinos A., Gobbo A., Gordon E., Huet J., Kieffer J., Lentini M., Mattenet M., Morawe C., Mueller-Dieckmann C., Ohlsson S., Schmid W., Surr J., Theveneau P., Zerrad L., McSweeney S., Upgraded ESRF BM29 beamline for SAXS on macromolecules in solution. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 20, 660–664 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olijve L., Sun Tianjun, Narayanan T., Jud C., Davies P. L., Voets I. K., Solution structure of hyperactive type I antifreeze protein. RSC Adv. 3, 5903–5908 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang W. K., Pan H., Wang F., Jiang M., Deng X., Li J., A rapid sample processing method to observe diatoms via scanning electron microscopy. J. Appl. Phycol. 27, 243–248 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gwak I. G., Jung W. s., Kim H. J., Kang S.-H., Jin E., Antifreeze protein in Antarctic marine diatom, Chaetoceros neogracile. Mar. Biotechnol. 12, 630–639 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bayer-Giraldi M., Weikusat I., Besir H., Dieckmann G., Characterization of an antifreeze protein from the polar diatom Fragilariopsis cylindrus and its relevance in sea ice. Cryobiology 63, 210–219 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Celik Y., Drori R., Pertaya-Braun N., Altan A., Barton T., Bar-Dolev M., Groisman A., Davies P. L., Braslavsky I., Microfluidic experiments reveal that antifreeze proteins bound to ice crystals suffice to prevent their growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1309–1314 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/8/e1701440/DC1

fig. S1. Amino acid sequence of MpAFP.

table S1. Crystallographic statistics for the RIC, RIII_1–4, RIII_5, and RV of MpAFP.

table S2. NMR structural statistics of MpAFP_RIN.

table S3. Parameters obtained from SAXS experiments.

table S4. Statistics of homology modeling studies (Phyre2 Server) on the OM protein TolC of M. primoryensis.

movie S1. M. primoryensis binds to C. neogracile to form a multicellular cluster and moves the mass through the medium.

movie S2. M. primoryensis does not interact with F. cylindrus.

movie S3. M. primoryensis moves the mixed-cell cluster through the medium and secures it to ice (top left corner).

movie S4. The ice-bound cell cluster of M. primoryensis and C. neogracile can resist displacement by fluid flow.