Abstract

Ketamine inhibits pentameric ligand-gated ion channels (pLGICs), including the bacterial pLGIC from Gloeobacter violaceus (GLIC). The crystal structure of GLIC shows R-ketamine bound to an extracellular intersubunit cavity. Here, we performed molecular dynamics simulations of GLIC in the absence and presence of R- or S-ketamine. No stable binding of S-ketamine in the original cavity was observed in the simulations, largely due to its unfavorable access to residue D154, which provides important electrostatic interactions to stabilize R-ketamine binding. Contrary to the symmetric binding shown in the crystal structure, R-ketamine moved away from some of the binding sites and was bound to GLIC asymmetrically at the end of simulations. The asymmetric binding is consistent with the experimentally measured negative cooperativity of ketamine binding to GLIC. In the presence of R-ketamine, all subunits showed changes in structure and dynamics, irrespective of binding stability; the extracellular intersubunit cavity expanded and intersubunit electrostatic interactions involved in channel activation were altered. R-ketamine binding promoted a conformational shift toward closed GLIC. Conformational changes near the ketamine-binding site were propagated to the interface between the extracellular and transmembrane domains, and further to the pore-lining TM2 through two pathways: pre-TM1 and the β1–β2 loop. Both signaling pathways have been predicted previously using the perturbation-based Markovian transmission model. The study provides a structural and dynamics basis for the inhibitory modulation of ketamine on pLGICs.

Introduction

As a general anesthetic, ketamine has recently gained renewed interest for scientific discoveries (1, 2, 3) and expanded clinical applications (4, 5, 6, 7). Although it is commonly known as a noncompetitive antagonist of NMDA receptors (8, 9, 10), ketamine has additional mechanisms of action besides just NMDA receptor blockade (2, 3, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). Ketamine increases cholinergic tone in the cortex (16) and inhibits nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) (17, 18), which belong to the family of pentameric ligand-gated ion channels (pLGICs). pLGICs play a major role in converting synaptic chemical signals into electrical impulses in the central and peripheral nervous systems and are targets of general anesthetics (19, 20). Inhibition of the pLGIC α7nAChR by ketamine and its metabolites has recently been linked to a potential treatment for major depression (2, 14). Thus, it is of broad interest to understand the underlying mechanism of ketamine inhibition of pLGICs.

In addition to eukaryotic pLGICs, ketamine also inhibits the prokaryotic GLIC (21), a proton-gated pLGIC from Gloeobacter violaceus (22). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ketamine is 58 μM at the proton concentration eliciting 20% of the maximal GLIC current (EC20) (21). The Hill coefficient of 0.9 ± 0.05, obtained from fitting the ketamine concentration-dependent inhibition curve (21), suggests negative cooperativity in ketamine binding to GLIC. Even at pH 4 (EC100), which elicits the maximal GLIC current, ketamine still significantly inhibits GLIC but requires a much higher concentration (Fig. S1), comparable to that used for cocrystallizing ketamine with GLIC (21). Brief preincubation with ketamine slows down GLIC activation substantially, suggesting that ketamine can also bind to the closed channel and stabilizes the closed conformation (Fig. S1). The crystal structure of GLIC-ketamine shows that ketamine occupies all five equivalent pockets between adjacent subunits in the extracellular domain (ECD) (21). R-ketamine (R-ket), rather than its enantiomer S-ketamine (S-ket), fits better to the x-ray electron density in the binding pocket (21). In addition to ketamine, crystal structures of GLIC have been determined in the absence (23) and presence of various anesthetics, including propofol and desflurane (24), ethanol (25), and bromoform (26). Among these available structures, ketamine is unique and binds to the ECD, unlike other anesthetics that bind to the TMD (24, 25, 26).

Contrary to their profound functional effects on GLIC, neither ketamine nor propofol introduced significant changes in the crystal structures of GLIC (21, 24). In other words, structures of GLIC bound to these anesthetics are virtually the same as the apo open structure (PDB: 3EAM) (23). A similar result was also observed in crystal structures of anesthetic- or alcohol-bound ELIC (27, 28, 29), another prokaryotic pLGIC. These observations beg the need for a different tool to elucidate structural changes that account for the functional changes induced by anesthetics.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been used previously to predict binding sites and affinities of anesthetics (24, 26, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34) and to determine changes in channel structures and dynamics upon anesthetic binding (35, 36, 37, 38). A multisite-binding mode has been identified for the anesthetics isoflurane, halothane, and propofol (30, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37). It has been shown that the same site can feature different binding poses and that anesthetics may migrate between different sites to introduce distinct functional changes (24, 34). MD simulations have also shown that, contrary to the symmetric occupancy of five equivalent sites in the crystal structure (24), asymmetric binding of propofol to GLIC accelerates transitions from an open to a closed conformation (38). No MD simulation has been done previously on ketamine binding to pLGICs.

Here, we performed MD simulations on crystal structures of GLIC in the absence and presence of ketamine. The simulation results suggest that, consistent with x-ray data, R-ket binding is more stable than S-ket to the ECD of GLIC. However, contrary to the symmetric binding shown in the crystal structure, R-ket binds asymmetrically to GLIC by the end of multiple replicate simulations. R-ket binding introduced a series of structural changes to areas ranging from the ECD binding site to the pore in the TMD, and promoted channel closure. The findings provide a structural and dynamics basis for understanding allosteric anesthetic action on pLGICs.

Materials and Methods

System preparation and MD simulations

Three systems were prepared for MD simulations based on the crystal structure (PDB: 4F8H) of GLIC bound with ketamine (21): 1) R-ket bound symmetrically to five equivalent sites of GLIC as shown in the x-ray structure, 2) S-ket in place of all five R-ket molecules in the x-ray structure, and 3) a control system without ketamine (apo GLIC). GLIC was embedded into a preequilibrated POPE/POPG (3:1) lipid mixture and fully hydrated in TIP3P water (Fig. S2). Each simulation system is a hexagonal prism with dimensions 105 × 105 × 130 Å and contains 1 GLIC, 167 POPE, 54 POPG, ∼25,000 water molecules, and five ketamine molecules whenever present. Sodium and chloride ions were added to neutralize the systems and provide ∼100 mM salt concentration. Each system contains a total of ∼127,000 atoms.

Protonation states of ionizable residues in GLIC were assigned using pKa calculations (23) to mimic acidic pH and fine-tuned as reported in Cheng et al. (36) and Mowrey et al. (38). Geometries and CHARMM-compatible parameters of R-ket and S-ket were obtained using a similar method as reported previously for other anesthetics (38, 39). Briefly, the parameterization followed the ffTK protocol based on the principles of the CHARMM General Force Field for druglike molecules (40). The optimized ketamine structures and parameters are provided in the Supporting Material (Fig. S3; Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4).

MD simulations were carried out using NAMD 2.11 (41). The CHARMM36 force field with cross-term map correction was used for protein, water, ions, and lipids (42, 43, 44). Each system was energy minimized for 20,000 steps and equilibrated for 2 ns, during which GLIC backbone restraints (10 kcal·mol−1·Å−2) were gradually reduced to zero. We performed three replicate 100-ns simulations for each system. MD simulations were performed at constant pressure (P = 1.01325 bar) and temperature (T = 310 K), with a 2-fs time step in all production simulations. Long-range electrostatic forces were evaluated by the PME algorithm (45). Periodic boundary conditions, water wrapping, and hydrogen atoms constrained with SHAKE were utilized in all simulations. Bonded and short-range nonbonded interactions were computed every step, whereas full electrostatic interactions were evaluated every two steps. The cutoff distance for nonbonded interactions was 12 Å and a smoothing function was applied for van der Waals interactions at a distance of 10 Å. The nonbonded pair list was calculated every 20 time steps with a pair-list distance of 13.5 Å.

Data analysis

VMD (46) was used for visualization and data analysis, including calculations of RMSD, RMSF, displacements, and pore hydration. Pore radii were calculated using the HOLE program (47). One-thousand frames with a 100-ps time interval were taken from each simulation for data analysis. Pore hydration status was defined and calculated as reported in Mowrey et al. (38) and Beckstein and Sansom (48). The histograms showing pore hydration status were generated using MATLAB2016a (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). The radial and lateral tilt angles of the pore-lining TM2 helices relative to the membrane normal were calculated following the method described in our earlier publications (30, 38). Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 7.0a software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Electrostatic interactions play a significant role in ketamine binding to GLIC

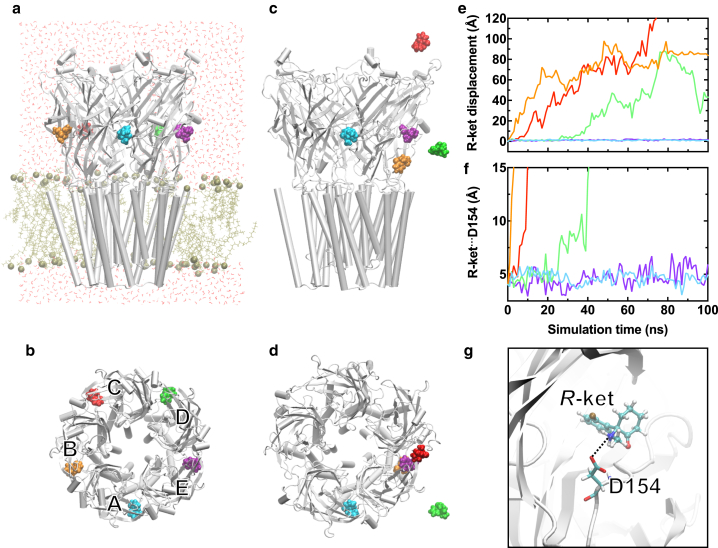

As shown in the crystal structure (21), ketamine was symmetrically bound to five equivalent sites in the ECD of GLIC at the beginning of MD simulations. Over the course of the simulations, some ketamine molecules remained in their original sites whereas others moved away (Fig. 1, a–d). No single system had ketamine bound to GLIC symmetrically by the end of simulations. The observed asymmetric ketamine binding is in line with the negative cooperativity measured by the Hill coefficient of 0.9 ± 0.05 (21). Binding stability of ketamine at each site was quantified by ketamine displacement from the original site (Fig. 1 e). Although the binding pocket has hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions with ketamine (21), electrostatic interactions seem to be a dominant factor in stabilizing ketamine binding. For example, the salt bridge (49) between the amine nitrogen atom of R-ket and the side-chain carbonyl oxygen atom of D154 (Fig. 1, f and g) accompanied stable R-ket binding in subunits A and E (Fig. 1 e, cyan and purple). Soon after the electrostatic interaction was destroyed, R-ket originally bound to subunit D migrated out of the pocket (Fig. 1 f, green). N152 also interacted with R-ket through hydrogen bonding. Mutation of N152C weakened ketamine inhibition effects on GLIC (21). Unlike R-ket, the amine nitrogen of S-ket has unfavorable access to residues D154 and N152. No S-ket remained in the original binding site and most S-ket moved into the solvent by the end of simulations (Fig. S4). The results are consistent with the crystal structure, in which R-ket, and not S-ket, binds to GLIC (21).

Figure 1.

R-ket binding to GLIC. (a) Given here are side and (b) top views of R-ket binding sites in the crystal structure of GLIC (PDB: 4F8H) at the beginning of MD simulations. POPE/POPG lipids and water molecules in (a) are colored in tan and red, respectively. (c and d) Given here are side and top views of R-ket binding after 100 ns of MD simulation, showing that two R-ket molecules (cyan and purple) remained in the original binding sites. (e) Shown here are displacements of R-ket, measured by the center of mass, over the course of MD simulations. (f) Distances between R-ket amine nitrogen and D154 side-chain carbonyl oxygen over the course of MD simulations are given. Note that R-ket molecules (cyan and purple) within the salt-bridge distance with D154 are the same R-ket showing stable binding in (c–e). (g) Given here is a representative snapshot showing electrostatic interactions between R-ket and D154 of GLIC. To see this figure in color, go online.

Ketamine binding altered the flexibility of GLIC

Ketamine binding to the ECD had a strong impact on the structure and dynamics of GLIC. Relative to the crystal structure, the overall backbone root-mean-square deviations (RMSDs) reached a plateau of 2.5 ± 0.3 Å in apo GLIC, but 3.4 ± 0.4 Å in the presence of R-ket (Fig. S5). The higher RMSD in ketamine-bound systems resulted mainly from changes in the ECD, reflecting the structural disturbance due to extracellular ketamine binding. In contrast, the TMD showed an RMSD plateau below ∼2 Å in all simulation systems.

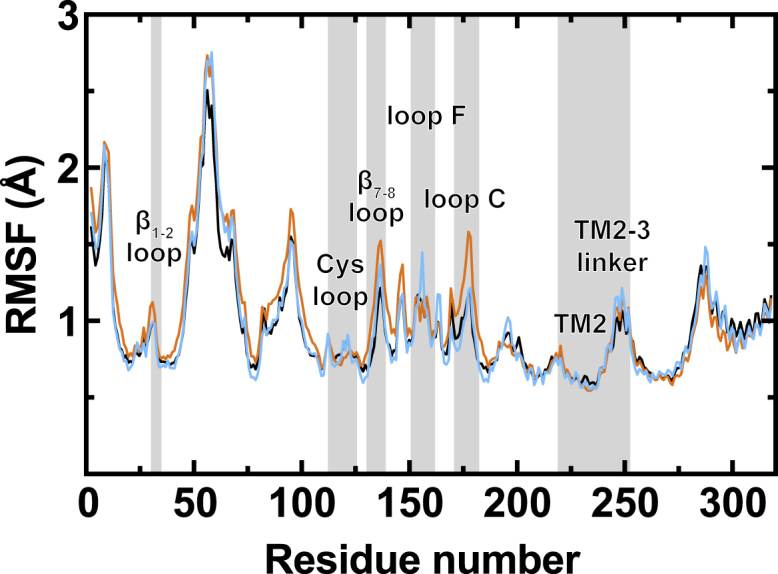

The effect of ketamine binding on GLIC dynamics was evaluated by the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of Cα atoms (Figs. 2 and S6). The results suggest that ketamine binding increases GLIC flexibility, especially in the ECD. For R-ket (Fig. 2), 81% of the ECD residues showed an increase in RMSF as compared to apo GLIC. Interestingly, the ketamine effect on RMSF is more profound in subunits without stable binding. The higher flexibilities in loop F, loop C, pre-TM1, and TM2-3 linker regions in the ketamine system are likely related to the channel closure because these regions are involved in GLIC conformational transitions. The S-ket system showed increased RMSF in 73% of the ECD residues compared to apo GLIC (Fig. S6). Crystallographic data from closed and open GLIC also show that closed GLIC has higher intrinsic flexibility (50).

Figure 2.

R-ket effects on the RMSFs of GLIC. Average Cα RMSF over the course of the last 50 ns of the simulations, from three replicates for each system, was calculated for the apo system (black) and R-ket system that contains GLIC subunits with stable (cyan, four subunits) and unstable (orange, 11 subunits) R-ket binding. To see this figure in color, go online.

Ketamine binding promoted channel closure

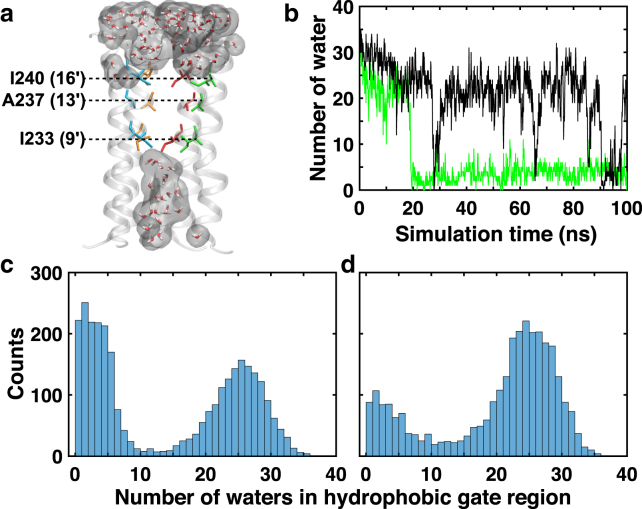

Compared to apo GLIC, the pore radius expands in the ECD and contracts in the TMD upon ketamine binding (Fig. S7). Pore-lining residues I240 (16′), A237 (13′), and I233 (9′) in TM2 form a hydrophobic gate (Fig. 3 a), where the hydration status of this region determines ion permeation across the channel (36, 38). At the beginning of simulations, water filled the hydrophobic gate region in each system. Over the course of simulations, the hydrophobic gate region in the apo system remained fully hydrated (>10 water) for ∼80% of the simulation time, but only ∼50% in the R-ket (Fig. 3, b–d) and S-ket systems (Fig. S8). Dehydration status in the gate region is consistent with the contraction of pore radius in the hydrophobic gate, particularly near I240 (16′) where GLIC in R-ket and S-ket systems show larger contraction than apo GLIC (Fig. S7). Although both R-ket and S-ket exhibited accelerated channel closure compared to apo GLIC, only R-ket systems started to show pore dehydration within 25 ns.

Figure 3.

R-ket effects on hydration of the hydrophobic gate region. (a) A representative snapshot of dehydration in the hydrophobic gate region between residues I240 to I233 is given. For clarity, only four TM2 helices are shown. (b) Given here are the representative water counts in the hydrophobic gate region for the apo (black) and R-ket bound (green) systems. (c and d) Shown here are histograms of water counts in the hydrophobic gate region for (c) R-ket bound and (d) apo GLIC systems. Each system has 3000 structures from three replicates used for histogram calculations. To see this figure in color, go online.

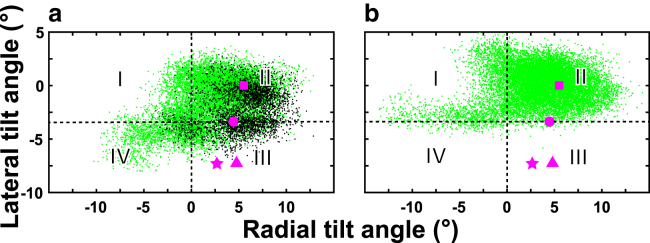

The channel hydration status is closely associated with the conformation of the pore, which can be characterized by the lateral and radial tilt angles of the TM2 helices (38, 51). GLIC in the apo system had a higher population of open or partially open channel conformations (∼83%) than the R-ket system (∼66%) (Fig. 4). The tilting angle data show that a group of GLIC structures from R-ket simulations closely resembles that of closed-channel crystal structures (50, 52). Within the R-ket system, we further analyzed the tilt angles of subunits with and without stable R-ket binding (Fig. 4 a) and found both types of subunits contributed to closed channel conformations. Thus, R-ket binding effects on GLIC structure were not limited to only those subunits with stable R-ket binding. Additionally, asymmetric radial and/or lateral tilting of TM2 helices occurred in simulations and was associated with the change of the hydration state of the channel (Fig. S9). Asymmetric movement of TM2 involved in the transition between an open and closed pore was also observed in previous simulations (38, 53, 54, 55). Experimental functional data support the involvement of asymmetric movement in channel function (56, 57). The TM2 tilt angle analysis also supports the notion that R-ket binding promotes channel closure.

Figure 4.

Distribution of radial and lateral tilting angles of TM2 helices from three replicate simulations (a) in the presence of R-ket or (b) apo GLIC. Black dots in (a) highlight TM2 tilt angles in subunits with stable R-ket binding. The TM2 tilting angles in crystal structures are marked for reference: magenta squares for the open-channel (PDB: 3EAM (23)), circles for the locally closed (PDB: 4NPP (50)), and triangles and stars for the two closed channels (PDB: 4LMK (52) and 4NPQ (50)), respectively. Four quadrants are defined by lateral and radial tilt angles of −3.4 and 0.0°, respectively. Quadrant II contains open conformations of GLIC. To see this figure in color, go online.

The signaling path from ketamine binding to the channel gate

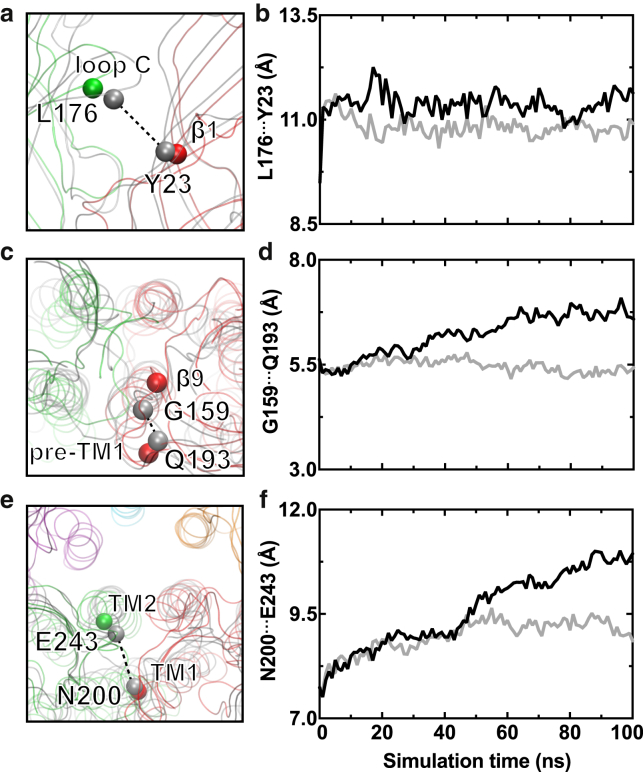

To search for how the ketamine-binding signal is transduced from the ECD to the TMD to promote channel closure, we analyzed structural changes along the signaling pathways predicted previously based on the perturbation-based Markovian transmission (PMT) model (58) in combination with Yen’s algorithm (59). Starting from regions near the R-ket binding site, we noticed expansion of the overall extracellular intersubunit pocket in the presence of R-ket (Fig. 5, a and b). Closer to the ECD-TMD interface, we observed a distance increase between G159 in β9 and Q193 in pre-TM1 (Fig. 5, c and d). Finally, the distance between N200 in TM1 and E243 in TM2 of the adjacent subunit increased (Fig. 5, e and f). Over the course of simulations, these changes from the binding pocket to pre-TM1 and further to the pore-lining TM2 are consistent with the pre-TM1 signaling pathway predicted previously using the PMT model (60). We also examined signal transduction pathways through the β1–β2 loop (Fig. S10). In the presence of R-ket, starting from the same residues in the ketamine-binding site (Fig. 5, a and b), along the β1–β2 signaling pathway we observed an increase in the distance between K33 of β1–β2 and T244 at the extracellular end of TM2 (Fig. S10, g and h).

Figure 5.

Conformational changes from the R-ket binding site in the ECD to the channel gate. Given here is a comparison of residue-pair Cα distances between (a and b) L176 and Y23 of the adjacent subunit, (c and d) G159 and Q193, and (e and f) E243 and N200 of the adjacent subunit in the R-ket and apo systems. Snapshots showing Cα distances at the end of apo (gray) and R-ket bound (green or red) simulations are shown in (a), (c), and (e). Average distances over all subunits in three replicate 100-ns simulations for apo (gray) and R-ket bound (black) systems are shown in (b), (d), and (f). To see this figure in color, go online.

We also compared GLIC from simulations with crystal structures, both open and closed (21, 50, 52). The distance expansion of those residue pairs in Figs. 5 and S10 is consistent with the blooming of the quaternary and tertiary ECD structure observed in the closed GLIC crystal structures (50). The loss of a conserved salt bridge between D32 and R192 due to the detachment of the inner and outer β-sheets is an important signature of closed GLIC (50). Therefore, we examined D32-R192 Cα distances in apo and R-ket simulations. The D32–R192 distance remained almost the same as that in the open crystal structure in apo simulations, but increased in the R-ket system similar to that observed in crystal structures of closed GLIC (Fig. S11, a and b). The redistribution of hydrophobic interactions, as measured by an increased distance between F195 in the pre-TM1 and M252 in the C-terminal end of the TM2-3 linker, was also reported as a characteristic of closed GLIC (50). Similarly, the distance between F195-M252 in the R-ket system simulations also increased (Fig. S11, c and d), consistent with an increase of closed GLIC in the presence of ketamine (Figs. 3 and 4).

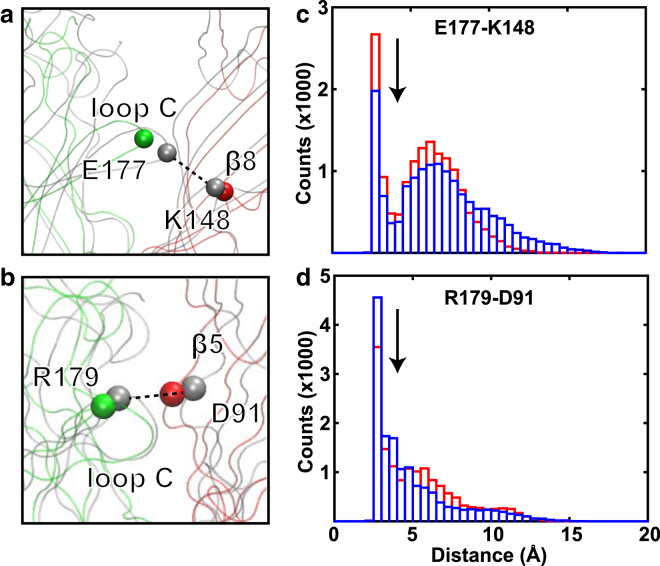

Effects of R-ket binding on the ECD intersubunit interface were evaluated by counting potential electrostatic contacts between E177 and K148 in the adjacent subunit (Fig. 6, a and c) and between R179 and D91 in the adjacent subunit (Fig. 6, b and d). In a previous study, simultaneously mutating these residues to disrupt their electrostatic interactions shifted channel activation toward a higher agonist concentration (60), suggesting that the mutations stabilized closed channels or destabilized open channels. In our simulations, the presence of R-ket reduced the probability of electrostatic interactions between E177 and K148 (Fig. 6 c) but increased the probability of electrostatic interactions for R179–D91 (Fig. 6 d). The positive association between the reduction of the E177–K148 interactions and channel closure (Figs. 3 and 4) in the presence of R-ket highlights a more important role for the E177–K148 contact than R179–D91 in the previously observed mutation effects (60). Because E177 is next to L176 (Fig. 5), ketamine effects on the E177–K148 interactions may also contribute to the signaling pathway for channel closure.

Figure 6.

R-ket effects on extracellular intersubunit interfaces. Given here are snapshots showing Cα distances between (a) E177 and K148 of the adjacent subunit and (b) R179 and D91 of the adjacent subunit at the end of apo (gray) and R-ket (green or red) simulations. Given also are histograms of distances (c) between E177 side-chain carbonyl oxygen and K148 side-chain nitrogen and (d) between R179 side-chain nitrogen and D91 side-chain carbonyl oxygen over three replicate simulations for R-ket bound (blue) and apo (red) systems. A bin size of 0.5 Å was used. Arrows indicate the 4 Å distance upper limit for stable salt-bridge formation. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Although R-ket binding to GLIC has been investigated previously by crystallographic and functional studies (21), the MD simulations provide additional molecular details for understanding ketamine inhibition of GLIC. Consistent with the crystal structure, the simulations show that R-ket, but not S-ket, have stable binding to the original cavity in GLIC. Despite the presence of hydrophobic and other hydrophilic interactions in the binding cavity, an unfavorable orientation of the S-ket amine nitrogen relative to D154 and N152 destabilized S-ket binding. These simulation results highlight the importance of electrostatic interactions in ketamine binding.

Consistent with ketamine’s inhibitory action on GLIC (21) and its stabilization of closed GLIC (Fig. S1), the presence of ketamine in simulations promotes GLIC toward closed conformations. The structural (Fig. 4; Figs. S7 and S11) and dynamic (Fig. 2) changes over the course of simulations have captured several elements related to gating transitions inferred from crystal structures of open and closed GLIC (50), including intrinsically higher flexibility in the ECD of closed GLIC, a quaternary reorganization of intersubunit interfaces and the associated binding pockets, tertiary structural changes as reflected in the detachment of the inner and outer β-sheets as well as in the pre-TM1, and the involvement of radial and lateral tilting of the TM2 in pore closure.

Crystal structures of GLIC show symmetric binding of ligands, including ketamine (21), propofol and desflurane (24), as well as bromoform and ethanol (25). The nonphysiologically high concentration of these anesthetics used in crystallization may have contributed to the observed binding to all five equivalent sites in GLIC crystal structures. When these crystal structures were used for MD simulations without restraining the ligands, the symmetric binding pattern often became asymmetric due to migration of some modulators, even after a relatively short simulation time (30, 38). This loss of symmetric ligand binding has also been observed in simulations of other pLGICs (61). The GLIC simulations with R-ket here followed the same trend and only one or two R-ket molecules remained stable in the extracellular intersubunit pocket (Figs. 1 and S4). One may simply attribute this asymmetric binding pattern to simulation artifacts; however, nonsimultaneous binding of ligands to all equivalent sites does have experimental bases. Ligands do not always have identical occupancy among five equivalent sites in GLIC crystal structures (21, 25, 26, 29). A number of pLGIC crystal structures even show asymmetric ligand binding (62, 63). In the case of ketamine binding to GLIC, the asymmetric binding pattern in the simulations agrees with the negative cooperativity of ketamine as measured by its Hill coefficient (0.9 ± 0.05). Functional measurements in combination with site-directed mutagenesis also demonstrate that homo-pLGICs, such as α7nAChR (64, 65), α1GlyR (66), and ρ1GABA receptors (67), can reach the maximum channel-gating efficacy without agonist binding to all five equivalent sites. Binding of the antagonist α-bungarotoxin to a single site has been found to fully suppress channel opening in α7nAChR (68). Occupation of a single binding pocket in α1GlyR by ethanol or chloroform is sufficient to enhance channel currents (69).

Asymmetric propofol binding to GLIC has been found to facilitate conformational changes and channel closure (38). A recent simulation study also observed that asymmetric propofol binding induced asymmetric conformational changes in GLIC (70). R-ket was asymmetrically bound to GLIC for the majority of our simulations. Compared to the apo system, the presence of R-ket undeniably accelerated channel closure in the simulations (Figs. 3 and 4). Moreover, ketamine effects were not limited to only the stable R-ket bound subunits, as subunits without stable binding also contributed to channel closure (Fig. 4). Microsecond MD simulations of GLIC have also observed a domino effect in channel closure, triggered by changes in a single subunit (71). In addition to simulation studies, structural variations among individual subunits of homo-oligomers have been observed in experimental results, including the crystal structure of the resting state GLIC, particularly the ECD (50), the crystal structure of an intermediate conformation of a trimeric transporter (72), and cryo-EM structures of open conformational states of pentameric CorA (73).

We have previously reported two major pathways for signal transduction from the ECD of pLGICs to the channel gate (60), either via pre-TM1 or the β1–β2 loop, predicted using the coarse-grained PMT model (58) in combination with Yen’s algorithm (59). Conformational changes along these two signaling pathways from the ketamine-binding site to the channel gate were observed in our R-ket simulations (Figs. 5 and S10). Although this study is focused on GLIC, the identified pathways can be generalized to other pLGICs. Both signaling pathways are well supported by experimental data on eukaryotic pLGICs (74, 75, 76, 77). Indeed, eukaryotic pLGICs, such as α7 and α4β2nAChR, share the homologous ketamine-binding site with GLIC (21), as well as functional inhibition by ketamine (17, 18). Thus, the findings reported here in GLIC can potentially be applied to eukaryotic pLGICs.

Author Contributions

P.T. and X.Y. conceived the project. P.T. designed the research. B.F.I. and M.M.W. performed the research and analyzed the data. Q.C. performed electrophysiology measurements in the Supporting Material. B.F.I., M.M.W., and P.T. wrote the article. P.T. and Y.X. supervised the project.

Acknowledgments

The simulation study was supported in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through XSEDE resources (MCB040002). The research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01GM056257 and R01GM066358).

Editor: Vasanthi Jayaraman.

Footnotes

Eleven figures and four tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30691-4.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Mashour G.A. Network-level mechanisms of ketamine anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:830–831. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul R.K., Singh N.S., Wainer I.W. (R,S)-Ketamine metabolites (R,S)-norketamine and (2S,6S)-hydroxynorketamine increase the mammalian target of rapamycin function. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:149–159. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zanos P., Moaddel R., Gould T.D. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature. 2016;533:481–486. doi: 10.1038/nature17998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erstad B.L., Patanwala A.E. Ketamine for analgosedation in critically ill patients. J. Crit. Care. 2016;35:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persson J. Ketamine in pain management. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2013;19:396–402. doi: 10.1111/cns.12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher A.D., Rippee B., Shehan H., Conklin C., Mabry R.L. Prehospital analgesia with ketamine for combat wounds: a case series. J. Spec. Oper. Med. 2014;14:11–17. doi: 10.55460/BO8F-KYQT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeWilde K.E., Levitch C.F., Iosifescu D.V. The promise of ketamine for treatment-resistant depression: current evidence and future directions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015;1345:47–58. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald J.F., Miljkovic Z., Pennefather P. Use-dependent block of excitatory amino acid currents in cultured neurons by ketamine. J. Neurophysiol. 1987;58:251–266. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.58.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebert B., Mikkelsen S., Borgbjerg F.M. Norketamine, the main metabolite of ketamine, is a non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist in the rat cortex and spinal cord. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;333:99–104. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sałat K., Siwek A., Popik P. Antidepressant-like effects of ketamine, norketamine and dehydronorketamine in forced swim test: role of activity at NMDA receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2015;99:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malinow R. Depression: ketamine steps out of the darkness. Nature. 2016;533:477–478. doi: 10.1038/nature17897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sleigh J., Harvey M., Denny B. Ketamine—more mechanisms of action than just NMDA blockade. Trends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care. 2014;4:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirota K., Lambert D.G. Ketamine: new uses for an old drug? Br. J. Anaesth. 2011;107:123–126. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Velzen M., Dahan A. Ketamine metabolomics in the treatment of major depression. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:4–5. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moaddel R., Abdrakhmanova G., Wainer I.W. Sub-anesthetic concentrations of (R,S)-ketamine metabolites inhibit acetylcholine-evoked currents in α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013;698:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pal D., Hambrecht-Wiedbusch V.S., Mashour G.A. Electroencephalographic coherence and cortical acetylcholine during ketamine-induced unconsciousness. Br. J. Anaesth. 2015;114:979–989. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coates K.M., Flood P. Ketamine and its preservative, benzethonium chloride, both inhibit human recombinant α7 and α4β2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:871–879. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamakura T., Chavez-Noriega L.E., Harris R.A. Subunit-dependent inhibition of human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and other ligand-gated ion channels by dissociative anesthetics ketamine and dizocilpine. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1144–1153. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200004000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campagna J.A., Miller K.W., Forman S.A. Mechanisms of actions of inhaled anesthetics. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2110–2124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemmings H.C., Jr., Akabas M.H., Harrison N.L. Emerging molecular mechanisms of general anesthetic action. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;26:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan J., Chen Q., Tang P. Structure of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel GLIC bound with anesthetic ketamine. Structure. 2012;20:1463–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bocquet N., Prado de Carvalho L., Corringer P.J. A prokaryotic proton-gated ion channel from the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor family. Nature. 2007;445:116–119. doi: 10.1038/nature05371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bocquet N., Nury H., Corringer P.J. X-ray structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel in an apparently open conformation. Nature. 2009;457:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature07462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nury H., van Renterghem C., Corringer P.J. X-ray structures of general anaesthetics bound to a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2011;469:428–431. doi: 10.1038/nature09647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauguet L., Howard R.J., Delarue M. Structural basis for potentiation by alcohols and anaesthetics in a ligand-gated ion channel. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1697. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurent B., Murail S., Baaden M. Sites of anesthetic inhibitory action on a cationic ligand-gated ion channel. Structure. 2016;24:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Q., Wells M.M., Tang P. Structural basis of alcohol inhibition of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel ELIC. Structure. 2017;25:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Q., Kinde M.N., Tang P. Direct pore binding as a mechanism for isoflurane inhibition of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel ELIC. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13833. doi: 10.1038/srep13833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spurny R., Billen B., Ulens C. Multisite binding of a general anesthetic to the prokaryotic pentameric Erwinia chrysanthemi ligand-gated ion channel (ELIC) J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:8355–8364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.424507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willenbring D., Liu L.T., Tang P. Isoflurane alters the structure and dynamics of GLIC. Biophys. J. 2011;101:1905–1912. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brannigan G., LeBard D.N., Klein M.L. Multiple binding sites for the general anesthetic isoflurane identified in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor transmembrane domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14122–14127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008534107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeBard D.N., Hénin J., Brannigan G. General anesthetics predicted to block the GLIC pore with micromolar affinity. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Q., Cheng M.H., Tang P. Anesthetic binding in a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel: GLIC. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1801–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brömstrup T., Howard R.J., Lindahl E. Inhibition versus potentiation of ligand-gated ion channels can be altered by a single mutation that moves ligands between intra- and intersubunit sites. Structure. 2013;21:1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L.T., Willenbring D., Tang P. General anesthetic binding to neuronal α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and its effects on global dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:12581–12589. doi: 10.1021/jp9039513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng M.H., Coalson R.D., Tang P. Molecular dynamics and Brownian dynamics investigation of ion permeation and anesthetic halothane effects on a proton-gated ion channel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16442–16449. doi: 10.1021/ja105001a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mowrey D., Haddadian E.J., Tang P. Unresponsive correlated motion in α7 nAChR to halothane binding explains its functional insensitivity to volatile anesthetics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:7649–7655. doi: 10.1021/jp1009675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mowrey D., Cheng M.H., Tang P. Asymmetric ligand binding facilitates conformational transitions in pentameric ligand-gated ion channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:2172–2180. doi: 10.1021/ja307275v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Z.W., Xu Y., Tang P. Parametrization of 2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1,1-trifluoroethane (halothane) and hexafluoroethane for nonbonded interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2004;108:781–786. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayne C.G., Saam J., Gumbart J.C. Rapid parameterization of small molecules using the force field toolkit. J. Comput. Chem. 2013;34:2757–2770. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacKerell A.D., Bashford D., Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacKerell A.D., Jr., Feig M., Brooks C.L., 3rd Improved treatment of the protein backbone in empirical force fields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:698–699. doi: 10.1021/ja036959e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Best R.B., Zhu X., MacKerell A.D., Jr. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ(1) and χ(2) dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald—an N.Log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smart O.S., Neduvelil J.G., Sansom M.S. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:354–360. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(97)00009-x. 376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beckstein O., Sansom M.S. The influence of geometry, surface character, and flexibility on the permeation of ions and water through biological pores. Phys. Biol. 2004;1:42–52. doi: 10.1088/1478-3967/1/1/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar S., Nussinov R. Close-range electrostatic interactions in proteins. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:604–617. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020703)3:7<604::AID-CBIC604>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sauguet L., Shahsavar A., Delarue M. Crystal structures of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel provide a mechanism for activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:966–971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314997111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang P., Mandal P.K., Xu Y. NMR structures of the second transmembrane domain of the human glycine receptor α(1) subunit: model of pore architecture and channel gating. Biophys. J. 2002;83:252–262. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75166-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gonzalez-Gutierrez G., Cuello L.G., Grosman C. Gating of the proton-gated ion channel from Gloeobacter violaceus at pH 4 as revealed by x-ray crystallography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:18716–18721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313156110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szarecka A., Xu Y., Tang P. Dynamics of heteropentameric nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: implications of the gating mechanism. Proteins. 2007;68:948–960. doi: 10.1002/prot.21462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yi M., Tjong H., Zhou H.X. Spontaneous conformational change and toxin binding in alpha7 acetylcholine receptor: insight into channel activation and inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8280–8285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710530105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haddadian E.J., Cheng M.H., Tang P. In silico models for the human α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:13981–13990. doi: 10.1021/jp804868s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grosman C., Auerbach A. Asymmetric and independent contribution of the second transmembrane segment 12′ residues to diliganded gating of acetylcholine receptor channels: a single-channel study with choline as the agonist. J. Gen. Physiol. 2000;115:637–651. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.5.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grandl J., Danelon C., Vogel H. Functional asymmetry of transmembrane segments in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur. Biophys. J. 2006;35:685–693. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu H.M., Liang J. Perturbation-based Markovian transmission model for probing allosteric dynamics of large macromolecular assembling: a study of GroEL-GroES. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yen J.Y. Finding the K shortest loopless paths in a network. Manage. Sci. 1971;17:712–716. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mowrey D., Chen Q., Tang P. Signal transduction pathways in the pentameric ligand-gated ion channels. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murail S., Wallner B., Lindahl E. Microsecond simulations indicate that ethanol binds between subunits and could stabilize an open-state model of a glycine receptor. Biophys. J. 2011;100:1642–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spurny R., Ramerstorfer J., Ulens C. Pentameric ligand-gated ion channel ELIC is activated by GABA and modulated by benzodiazepines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E3028–E3034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208208109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hibbs R.E., Gouaux E. Principles of activation and permeation in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor. Nature. 2011;474:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nature10139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andersen N., Corradi J., Bouzat C. Stoichiometry for activation of neuronal α7 nicotinic receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:20819–20824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315775110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams D.K., Stokes C., Papke R.L. The effective opening of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors with single agonist binding sites. J. Gen. Physiol. 2011;137:369–384. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beato M., Groot-Kormelink P.J., Sivilotti L.G. The activation mechanism of alpha1 homomeric glycine receptors. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:895–906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4420-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amin J., Weiss D.S. Insights into the activation mechanism of ρ1 GABA receptors obtained by coexpression of wild type and activation-impaired subunits. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1996;263:273–282. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.daCosta C.J., Free C.R., Sine S.M. Stoichiometry for α-bungarotoxin block of α7 acetylcholine receptors. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8057. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roberts M.T., Phelan R., Mihic S.J. Occupancy of a single anesthetic binding pocket is sufficient to enhance glycine receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:3305–3311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Joseph T.T., Mincer J.S. Common internal allosteric network links anesthetic binding sites in a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nury H., Poitevin F., Baaden M. One-microsecond molecular dynamics simulation of channel gating in a nicotinic receptor homologue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6275–6280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001832107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Verdon G., Boudker O. Crystal structure of an asymmetric trimer of a bacterial glutamate transporter homolog. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:355–357. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matthies D., Dalmas O., Subramaniam S. Cryo-EM structures of the magnesium channel CorA reveal symmetry break upon gating. Cell. 2016;164:747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chakrapani S., Bailey T.D., Auerbach A. Gating dynamics of the acetylcholine receptor extracellular domain. J. Gen. Physiol. 2004;123:341–356. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200309004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Purohit P., Auerbach A. Acetylcholine receptor gating: movement in the α-subunit extracellular domain. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;130:569–579. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee W.Y., Sine S.M. Principal pathway coupling agonist binding to channel gating in nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2005;438:243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature04156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bafna P.A., Purohit P.G., Auerbach A. Gating at the mouth of the acetylcholine receptor channel: energetic consequences of mutations in the αM2-cap. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.