Abstract

The purpose of our study was (a) to use latent class analyses to identify subgroups of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration among young pregnant couples and (b) examine actor–partner effects of latent classes on current intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization. Data were collected from 296 pregnant young couples recruited at obstetrics and gynecology clinics. A 3-latent class model emerged for women: Polyvictim-Polyperpetrator, Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator, and Community and Prior IPV Victim. A 4-latent class model emerged for men: Community and Prior IPV Victim, Polyvictim-Nonpartner Perpetrator, Prior IPV and Peer Victim, and Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator. Using the actor–partner independence model, actor effects of the women’s Polyvictim-Polyperpetrator class and men’s Polyvictim-Nonpartner Perpetrator class related to greater odds of IPV victimization compared to women and men in the Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator classes.

Keywords: young pregnant couples, intimate partner violence, polyvictimization, polyperpetration, latent class analysis

There is a growing recognition for the need for research and intervention efforts directed toward the prevention of intimate partner violence (IPV) in the United States. In the United States, various study designs and subpopulations of young men and women have reported the prevalence of physical IPV range from 9% to 46% (Offenhauer & Buchalter, 2011). Although it has been well-established that experiencing IPV is associated with adverse physical and mental health consequences for young women and men (Miller et al., 2010; Rhodes et al., 2009), there remains a dearth of studies examining IPV prevention efforts among subpopulations of young women and men, specifically pregnant young couples. This is concerning because the prevalence of physical IPV victimization is higher among pregnant adolescents compared to pregnant adults (Gazmararian et al., 1995). The handful of studies examining IPV among pregnant young couples highlight the negative parenting and child outcomes related to IPV (Gibson, Callands, Magriples, Divney, & Kershaw, 2015; Willie, Powell, & Kershaw, 2016); however, this body of research primarily focuses on the experiences of the mother. Although males are more likely to report use of sexual IPV aggression (O’Leary & Slep, 2012) and to inflict physical injury on a partner (Foshee et al., 1996), IPV prevention efforts need to understand how IPV develops and sustains (Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Capaldi, 2012; O’Leary & Slep, 2012) within the couple. Pregnant and parenting young couples are at-risk couples for IPV (O’Leary & Slep, 2012); thus, research examining risk factors of IPV victimization for both partners in an intimate couple is needed to inform the development and implementation of couple-based IPV interventions (Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Capaldi, 2012), for young couples.

CONCEPTUALIZING INTERPERSONAL POLYVICTIMIZATION AND POLYPERPETRATION

An underexplored but potentially informative risk factor for IPV among pregnant young couples is prior experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration. Polyvictimization and polyperpetration are emerging concepts capturing cumulative or multiple victimization and perpetration acts across and within contexts including IPV, community violence, family violence, and peer violence (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007, 2009; Hamby & Grych, 2013). To date, some literature on polyvictimization and polyperpetration define these concepts as the number of different victimization and perpetration experiences regardless of the broader category (e.g., family violence; Finkelhor et al., 2007; Scott-Storey, 2011); whereas other polyvictimization studies do consider the broader category such as community, family, peer violence (Hickman et al., 2013; Turner, Finkelhor, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2012). Building on existing polyvictimization and polyperpetration research, this study operationalizes interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration as experiencing multiple victimization and engaging in multiple perpetration acts specific to the broad category (e.g., family violence victimization and perpetration) and focusing primarily on the direct exposure of violence within an interpersonal context (e.g., between individuals). This approach highlights the relationship between the young couple member and either the perpetrator or victim, which may play an important role in one’s engagement in IPV in their current relationship.

A RATIONALE FOR EXAMINING INTERPERSONAL POLYVICTIMIZATION AND POLYPERPETRATION USING LATENT CLASS ANALYSES

Latent class analyses may be a powerful statistical technique to describe and understand experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration among young pregnant couples. In particular, latent class analysis (LCA) provides a nuanced and empirically based approach to identify homogenous subgroups of pregnant young couples based on prior experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration. After identifying the homogenous subgroups, individuals’ subgroup classification can be used to examine which subgroups are at the highest risk for IPV (Haegerich & Massetti, 2013). A growing body of polyvictimization literature uses LCA and other person-centered approaches to identify subgroups of young people based on experiences of violence (Adams et al., 2016; Ford, Elhai, Connor, & Frueh, 2010; Hamby, Finkelhor, & Turner, 2012; Turner, Shattuck, Finkelhor, & Hamby, 2015); however, this previous research has yet to identify subgroups of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration among pregnant young couples. This is concerning because young mothers are at a heightened risk for community violence, family violence (Kennedy, 2006), and IPV (Harrykissoon, Rickert, & Wiemann, 2002). In addition, some studies report a higher prevalence of community violence and IPV perpetration among young mothers and fathers compared to young nonparenting females and males (O’Donnell, Stueve, & Myint-U, 2009). Given the potential heterogeneity in violence among young pregnant couples, LCA is key to explore whether subgroups of pregnant young couples exist based on experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration, and if so, which subgroups may benefit from tailored prevention interventions.

LINKING PRIOR INTERPERSONAL POLYVICTIMIZATION AND POLYPERPETRATION TO CURRENT INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE VICTIMIZATION

The social learning theory provides a potential theoretical framework to explain a relationship between prior experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization, polyperpetration, and revictimization. In the context of violence, social learning theory states that direct observations and experiences with violent acts as either the victim and/or perpetrator may influence similar behaviors in the future (Bandura & McClelland, 1977; Markowitz, 2001). For example, experiencing childhood sexual abuse increases the risk of revictimization in adulthood (Gidycz, Coble, Latham, & Layman, 1993). Using social learning theory, prior experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration may influence IPV in future relationships. For example, experiencing family violence (Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004; Magdol, Moffitt, Caspi, & Silva, 1998), peer violence (O’Donnell et al., 2006), and IPV in past relationships (Cole, Logan, & Shannon, 2008) have independently been associated with IPV victimization. Specifically, experiencing victimization and engaging in perpetration across multiple domains may lead to a tolerance or acceptance of violence and an understanding that interpersonal actors (e.g., family member–family member) interact through violent acts (McClellan & Killeen, 2000). Although existing research suggest a significant relationship between victimization, perpetration, and revictimization, only a few studies examine prior polyvictimization and polyperpetration as risk factors for revictimization. One study found that child polyvictimization predicted revictimization in adulthood (Pereda & Gallardo-Pujol, 2014); however, several forms of victimization and perpetration were unexamined (e.g., community, peer), and this sample was limited to adults. Research exploring the influences of prior experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration is important because these experiences may impact the effectiveness of IPV prevention interventions among pregnant young couples.

THE IMPORTANCE OF EXPLORING BOTH INDIVIDUAL AND PARTNER EXPERIENCES OF VIOLENCE

IPV within pregnant young couples may be greatly influenced by dyadic behaviors (Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Capaldi, 2012); however, studies investigating victimization and perpetration at the couple level are scarce. One study measured victimization at the couple level, finding that both partners’ histories of family violence predicted physical IPV victimization in the current relationship (Fritz, Slep, & O’Leary, 2012). These findings are meaningful for understanding prior experiences of victimization as a risk factor for IPV within a couple; yet, this study examined only family violence and was limited to a sample of cohabitating adults. Because IPV may be a dyadic behavior among pregnant young couples, research is needed to understand whether prior experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration for each member in a couple impact the couple’s engagement in IPV.

THE PRESENT STUDY

Subgroups of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration may exist and predict IPV among pregnant young couples; however, significant gaps and limitations exist in the literature. This study seeks to fill these gaps and limitations in four distinct ways. First, latent class analyses were used to identify distinct subgroups of pregnant young women and men based on their prior experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration (e.g., community violence, family violence, peer violence, IPV in past relationships). Second, whereas examining latent classes of violence by gender has been conducted in adult samples (Ansara & Hindin, 2009), this approach is limited in adolescent populations. Separate latent class analyses were conducted by gender to explore patterns of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration that may be unique to pregnant young women and their male partners, especially given the research that young women and men have varying experiences of polyvictimization (Cuevas, Sabina, & Bell, 2014; Soler, Paretilla, Kirchner, & Forns, 2012). Third, the role of peers and early intimate relationships are often underexplored risk factors of IPV (Smith, Greenman, Thornberry, Henry, & Ireland, 2015); thus, this study included peer violence and prior IPV as latent class indicators to understand whether violence between peers and early intimate partners is a salient experience for pregnant young couples. Final, this study examined the impact of individual and dyadic associations (i.e., actor–partner effects) between women and men latent classes of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration on IPV victimization among pregnant young couples.

METHOD

Procedure

This study is a secondary data analysis of data collected from a longitudinal study designed to assess relationship changes from pregnancy to postpartum and the effects of those changes on the sexual, reproductive, and maternal health of pregnant adolescents and their male partners. Between July 2007 and February 2011, 296 pregnant couples (N = 592 participants) were recruited from obstetrics and gynecology clinics and an ultrasound clinic in four university-affiliated hospitals in Connecticut. Potential participants were screened for eligibility. Eligible participants were provided study information, and the research staff answered any questions. If the biological father or mother was absent at the screening, research staff asked for permission to contact their partner to explain the study. The participation rate for the longitudinal study was 72%. Participants were asked for reasons for declining to participate in the study, including whether the participant felt unsafe or uncomfortable to reach out to their partners because of IPV. If the participants revealed that they felt unsafe, protocols were in place to provide support for those participants; however, no participants endorsed they were unsafe. The only difference between those who enrolled in the study versus those who did not was that those who refused to participate were on average 2 weeks further along in their pregnancy compared to those who participated (p < .05).

Inclusion criteria for the study included (a) pregnant females in their second or third trimester of pregnancy, (b) both partners report being the biological parents of the unborn baby and in a romantic relationship with each other, (c) females between the age of 14 and 21 years old and male partners aged at least 14 years, (d) both partners agreed to participate in the study, and (e) able to speak English or Spanish. Because the study was longitudinal, an initial run-in period was conducted as part of the eligibility criteria; in particular, participants were deemed ineligible if they were unable to be recontacted after screening and before their estimated due date.

Data were collected at baseline (Time 1). During the baseline interview, the research staff obtained written informed consent. Each partner of the couple completed structured interviews by audio computer-assisted self-interviews, separately. At the end of the interview, participants were remunerated $25 and provided with a list of community resources including those for employment, mental health treatment, and violence-related services. Participants who disclosed IPV to the research staff were referred to clinical health professionals at the participating clinics. More details on the design of the prospective cohort study can be found at Kershaw et al. (2013). The study clinics and host institution’s institutional review boards approved all procedures.

For this study, we included participants with valid baseline data, resulting in a final sample of 296 females and 296 males. All sociodemographics, predictors, and outcomes were examined during baseline (Time 1).

Measures

Interpersonal polyvictimization latent class indicators were family violence victimization, community violence victimization, peer violence victimization, and prior IPV victimization. Interpersonal polyperpetration latent class indicators were family violence perpetration, community violence perpetration, peer violence perpetration, and prior IPV perpetration. This categorization of polyvictimization and polyperpetration acts is similar to other studies (Ford, Wasser, & Conner, 2011; Turner et al., 2012). These victimization and perpetration indicators were assessed using two items from the Physical Assault subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003) and five items from the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss & Oros, 1982). Participants were asked to report if they experienced physical (e.g., ever shoved, punched, hit, slapped, or physically hurt) and sexual violence (e.g., ever forced to have sex) with anyone other than their current partner. Also, participants were asked to report if they perpetrated physical (e.g., ever shoved, punched, hit, slapped, or physically hurt) and sexual violence (e.g., ever forced them to have sex) with anyone other than their current partner. If they answered yes to either the victimization and/or perpetration questions, they were asked to report whether that person was either a family member, partner’s family member, friend, acquaintance, stranger, or previous partner.

Family Violence Victimization and Perpetration

If they answered in the affirmative to any of these victimization acts (e.g., physical—ever shoved, punched, hit, slapped, or physically hurt; sexual—ever forced to have sex) with a family member or partner’s family member, they were recorded as family violence victimization. If they answered in the affirmative to any of these perpetration acts with a family member or partner’s family member, they were recorded as family violence perpetration.

Community Violence Victimization and Perpetration

If they answered in the affirmative to any of these victimization acts (e.g., physical—ever shoved, punched, hit, slapped, or physically hurt; sexual—ever forced to have sex) with an acquaintance, or stranger, they were recorded as community violence victimization. If they answered in the affirmative to any of these perpetration acts with an acquaintance, or stranger, they were recorded as community violence perpetration. The categorization of violence by an acquaintance and stranger is consistent with existing literature, which defines community violence as violence in a neighborhood by nonintimate, known and unknown partners (Linares et al., 2001).

Peer Violence Victimization and Perpetration

If they answered in the affirmative to any of these victimization acts (e.g., physical—ever shoved, punched, hit, slapped, or physically hurt; sexual—ever forced to have sex) with a friend, they were recorded as peer violence victimization. If they answered in the affirmative to any of these perpetration acts with a friend, they were recorded as peer violence perpetration.

Prior Intimate Partner Violence Victimization and Perpetration

If they answered in the affirmative to any of these victimization acts (e.g., physical—ever shoved, punched, hit, slapped, or physically hurt; sexual—ever forced to have sex) with a previous romantic or dating partner, they were recorded as prior IPV victimization. If they answered in the affirmative any of these perpetration acts with a previous romantic or dating partner, they were recorded as prior IPV perpetration.

Current Partner IPV victimization was assessed using two items from the Physical Assault subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus et al., 2003) and five items from the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss & Oros, 1982). Participants reported if they experienced physical victimization (e.g., current partner ever shoved, punched, hit, slapped, or physically hurt them) and sexual victimization (e.g., current partner ever forced them to have sex) from their current partner. If they answered in the affirmative to any of these victimization acts with the current partner, they were recorded as current partner IPV victimization.

The participants reported sociodemographics such as age, household income, race, gender, years of education, and employment status.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted and compared by gender (Table 1). Next, we explored patterns of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration using LCA (McCutcheon, 1987). We conducted two separate LCAs: (a) women’s interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration, and (b) men’s interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration. We used the following goodness of fit measures to determine the optimal number of latent classes: Akaike information criterion and adjusted Bayesian information criteria, and entropy. The lowest values for the Akaike information criterion and adjusted Bayesian information criteria illustrate the better fitting model. Furthermore, entropy greater than or equal to .80 demonstrates that the latent classes are distinct from one another (Celeux & Soromenho, 1996). The names of the latent classes were based on whether or not the probability of reporting the specific violence victimization and/or perpetration was at least .50.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Characteristics of the Sample

| Females | Males | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| (N = 296) | (N = 296) | p | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years): M (SD) | 18.71 (1.63) | 21.33 (4.06) | <.001 |

| Household income: M (SD) | 13,497 (15,530) | 17,439 (21,504) | <.001 |

| Race | <.001 | ||

| Black | 40.0 (117) | 48.0 (144) | .190 |

| White | 20.0 (62) | 15.0 (44) | |

| Hispanic | 40.0 (117) | 36.0 (108) | |

| Employment | .190 | ||

| Unemployed | 72.0 (212) | 40.0 (116) | |

| Part-time | 21.0 (61) | 29.0 (86) | |

| Full-time | 7.0 (23) | 31.0 (92) | |

| Years of education: M (SD) | 11.75 (1.82) | 11.84 (1.89) | .450 |

| Predictors | |||

| Victimization | |||

| Community violence | 22.6 (67) | 21.6 (64) | .004 |

| Prior IPV | 32.8 (97) | 27.0 (80) | .438 |

| Family violence | 9.1 (27) | 8.4 (25) | .839 |

| Peer violence | 7.1 (21) | 12.8 (38) | .025 |

| Perpetration | |||

| Community violence | 7.1 (21) | 11.5 (34) | <.001 |

| Prior IPV | 11.8 (35) | 14.9 (44) | <.001 |

| Family violence | 4.4 (13) | 5.4 (16) | .378 |

| Peer violence | 4.7 (14) | 7.1 (21) | .289 |

| Outcome | |||

| Current partner IPV victimization | 12.8 (38) | 31.4 (93) | <.001 |

Note. Data are % (N) unless otherwise indicated. All variables were measured at baseline. IPV = intimate partner violence.

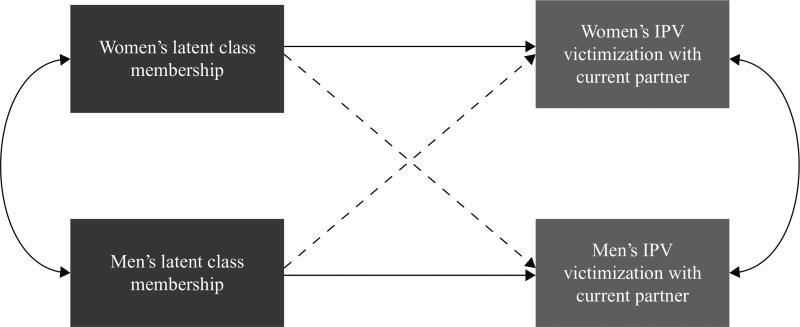

Path analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998) to assess the influence of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration latent class membership for young women and men on current partner IPV victimization using the actor–partner interdependence model (Figure 1). The actor–partner interdependence model has been used in romantic partner analyses among adolescents (Kershaw et al., 2013). One advantage of the actor–partner interdependence model is the ability to analyze responses from both members of the couple by assessing actor and partner effects (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Actor effects refer to the association of one’s own characteristic on one’s outcome (e.g., participant’s interpersonal polyvictimization latent class membership on participant’s experience of current partner IPV victimization). Partner effects refer to the association of partner’s characteristic influencing a participant’s outcome (e.g., partner’s interpersonal polyvictimization latent class membership on participant’s experience of current partner IPV victimization). All models controlled for covariates including age, income, education, race, and employment. It is important to note that this study did not include IPV perpetration as an outcome in the path analyses. Inclusion of current partner IPV perpetration and victimization in the same model would lead to redundancy (e.g., female partner victimization is measuring the same variable as male partner perpetration), resulting in a poorly fitted model and collinearity issues.

Figure 1.

Actor–partner interdependence model of hypothesized effects of female’s and male’s interpersonal latent class and intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization with the current partner for young parents. Dashed lines are partner effects, solid lines are actor effects, and bidirectional arrows are correlations.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Females and males were compared on all sociodemographics, predictors, and outcomes (see Table 1). The racial and ethnic makeup of the sample was African American (48% male; 40% female), Hispanic (36% male; 40% female), and White (15% male; 20% female). The employment status for the sample was unemployed (40% male; 72% female), part time (29% male; 21% female), and full time (31% male; 7% female). The average age for females was 18.7 years (SD = 1.63 years; range = 15–21 years) and for males 21.3 years (SD = 4.06 years; range = 14–40 years).

Differences in Victimization and Perpetration for Females and Males

Among the pregnant young couples, men reported more current partner IPV victimization than women (31% vs. 13%; McNemar χ2 = 14.18, p < .001). Almost a third of the sample of women (33%) and men (27%) reported experiencing IPV victimization in a previous intimate relationship. Similarly, 23% of women and 22% of men reported experiencing community violence victimization. Furthermore, the prevalence of family violence victimization among women was 9% and for men was 8%. Finally, men were more likely to experience peer violence victimization than women (13% vs. 7%; McNemar χ2 = 5.0, p = .01).

Men reported more IPV perpetration in prior relationships than women (14% vs. 11%; McNemar χ2 = 227.34, p = .004). Furthermore, 11% of males and 7% of women perpetrated community violence. There was a relatively low prevalence of perpetration for men and women across family and peer violence. In particular, only 5% of men and 4% of women reported perpetrating family violence, whereas 7% of men and 4% of women reported perpetrating peer violence.

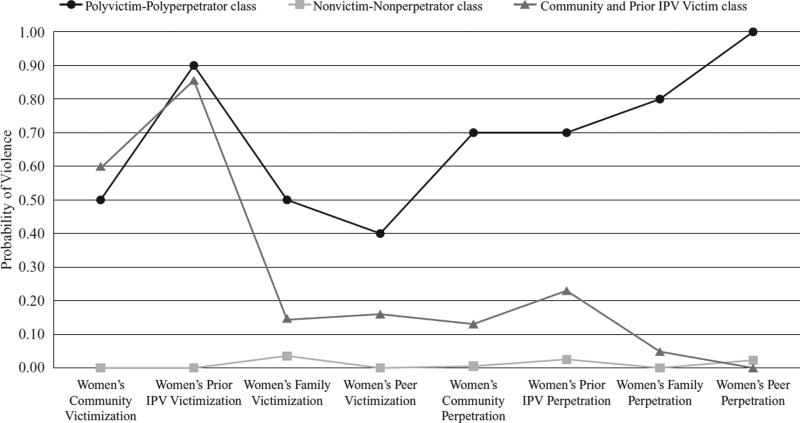

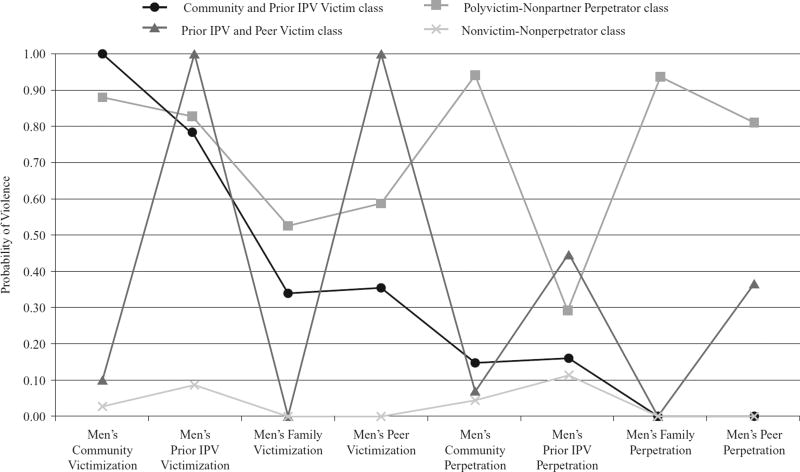

Fit Statistics

The fit statistics for prior experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration for young women and men are displayed in Table 2. These fit statistics revealed that the three-class model was the best fit for women and the four-class model was the best fit for men (see Table 2; Figures 2 and 3). These two models were chosen because of their small values for Akaike information criterion and adjusted Bayesian information criterion and having an entropy greater than .80.

TABLE 2.

Fit Statistics for Interpersonal Polyvictimization and Polyperpetration Latent Classes by Gender

| 2 Class | 3 Classes | 4 Classes | 5 Classes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| AIC | 1,379.80 | 1,475.14 | 1,336.23 | 1,419.77 | 1,340.10 | 1,405.25 | 1,347.14 | 1,420.46 |

| Adjusted BIC | 1,388.63 | 1,438.96 | 1,349.73 | 1,433.27 | 1,358.27 | 1,423.42 | 1,369.98 | 1,443.30 |

| Entropy | .86 | .89 | .94 | .90 | .91 | .96 | .86 | .95 |

| LMR LRT p value | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .23 | .01 | .123 | .53 |

| BLRT | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .37 | .00 | 1.00 | .33 |

|

| ||||||||

| Class prevalence | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

|

| ||||||||

| Class 1 | 107 (35.5) | 69 (23.3) | 10 (3.4) | 55 (20.9) | 10 (3.4) | 40 (13.8) | 50 (16.0) | 10 (3.9) |

| Class 2 | 189 (64.7) | 227 (76.7) | 188 (62.0) | 16 (5.4) | 187 (62.0) | 17 (5.8) | 9 (2.9) | 6 (2.2) |

| Class 3 | 98 (34.7) | 225 (73.7) | 9 (4.6) | 13 (4.5) | 9 (3.6) | 207 (70.7) | ||

| Class 4 | 90 (29.9) | 226 (75.9) | 37 (14.8) | 55 (17.2) | ||||

| Class 5 | 191 (62.7) | 18 (6.0) | ||||||

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; LMR LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; BLRT = bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

Figure 2.

Patterns of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration among young pregnant women (N = 296). IPV = intimate partner violence.

Figure 3.

Patterns of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration among young men (N = 296). IPV = intimate partner violence.

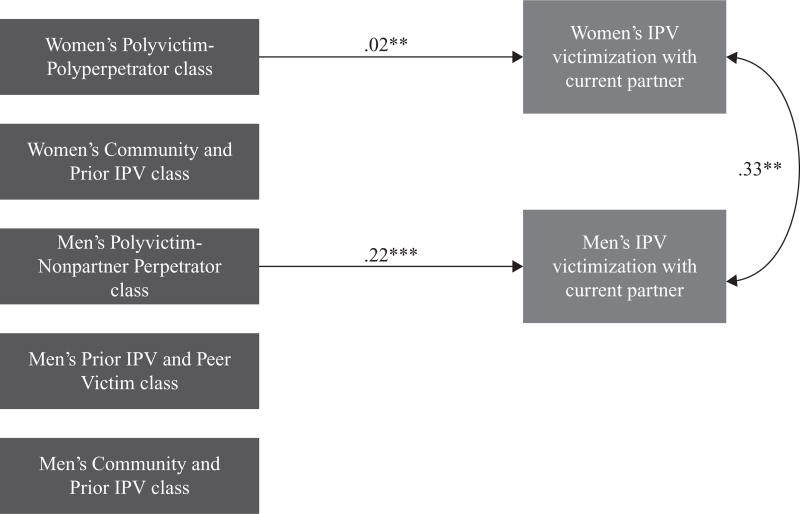

Table 3 shows the results for the final path model with each latent class (i.e., actor–partner effects) predicting IPV victimization in the current relationship while controlling for covariates. The fit statistics for the model indicates that the model was an adequate fit to the data (confirmatory fit index [CFI] = 1.00, Tucker-Lewis index [TLI] = 1.00, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.00).

TABLE 3.

Actor and Partner Effects of Interpersonal Polyvictimization and Polyperpetration Latent Classes on Intimate Partner Violence Victimization

| Women’s Current Partner IPV Victimization |

Men’s Current Partner IPV Victimization |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| β | OR | β | OR | |

| Women’s latent classes | ||||

| Polyvictim-Polyperpetrator class compared to Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator class | .02 | 1.02 | .09 | 1.09 |

| Community and Prior IPV Victim class compared to Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator class | .01 | 1.01 | .01 | 1.01 |

| Men’s latent classes | ||||

| Polyvictim-Nonpartner Polyperpetrator class compared to Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator class | .01 | 1.01 | .22 | 1.25 |

| Prior IPV and Peer Victim class compared to Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator class | .01 | 1.01 | .01 | 1.01 |

| Community and Prior IPV Victim class compared to Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator class | −.99 | 0.37 | −.15 | 0.86 |

Note. Covariates included in the model are age, household income, years of education, race, and employment. Values in boldface are significant at p < .05. IPV = intimate partner violence; OR = odds ratio.

Establishing the Latent Classes Based on Polyvictimization and Polyperpetration

Describing Female and Male Latent Classes

For the young women’s interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration three-latent class model, women in Class 1 or Polyvictim-Polyperpetrator class (3.4%) had high probabilities of reporting prior IPV and family violence victimization (i.e., domestic violence [DV]), in addition to reporting aggression toward prior intimate partners, family, community, and peers. Young women in Class 2 or Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator (62%) had low probabilities of all forms of victimization and aggression. Young women in Class 3 or Community and Prior IPV Victim class (34.7%) had high probabilities of reporting IPV experiences with a prior intimate partner.

For the men’s interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration four-latent class model, men in Class 1 or Community and Prior IPV Victim class (13.8%) had high probabilities of reporting prior IPV and community violence experiences. Men in Class 2 or Polyvictim-Nonpartner Perpetrator class (5.8%) had high probabilities of reporting victimization experiences by prior intimate partners, community, family, and peers, in addition to using aggression toward family, peers, and community members. Men in Class 3 or Prior IPV and Peer Victim class (4.5%) had high probabilities of reporting victimization experiences by prior intimate partners and peers. Men in Class 4 or Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator class (75.9%) had low probabilities of reporting victimization and perpetration experiences.

Examining the Effects of Latent Class Membership on Current Intimate Partner Violence Victimization

Actor and Partner Effects

The actor effects of the women Polyvictim-Polyperpetrator and the men Polyvictim-Nonpartner Perpetrator were directly related to IPV victimization in the current relationship (see Table 3; Figure 4). The odds of reporting IPV victimization within the current relationship were higher for women in the Polyvictim-Polyperpetrator class than men in the Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator class (odds ratio [OR] = 1.02, p < .01). Similarly, the odds of reporting IPV victimization within the current relationship was higher for men in the Polyvictim-Nonpartner Perpetrator class compared to the men in the Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator class (OR = 1.25, p = .001). There were no significant partner effects of latent class membership on IPV victimization in the current relationship for women and men.

Figure 4.

Final actor–partner interdependence model of the effects of women’s and men’s interpersonal latent class and intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization with the current partner for young pregnant couples. Only significant paths are shown. These latent classes were being compared to their respective Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator class. Solid lines are actor effects and bidirectional arrows are correlations.

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

DISCUSSION

Pregnant young couples have diverse experiences of interpersonal polyvictimization and engagement in polyperpetration, which can influence and shape their IPV experiences in current relationships. Building on extant polyvictimization and polyperpetration research, this is one of the first studies to identify patterns of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration among a currently overlooked population: pregnant young couples. Although our findings are similar to the handful of studies examining both victimization and perpetration subgroups among adolescents (Cuevas, Sabina, & Picard, 2010; Haynie et al., 2013; Whiteside et al., 2012), our results illustrate that experiences and engagement in violence across multiple domains is a salient reality for pregnant young couples because nearly one in three young women (38%) and men (24.1%) were categorized in a latent class with victimization or perpetration experiences. Furthermore, our findings support previous research by demonstrating that the role of a perpetrator-victim is complex (Hamby & Grych, 2013). In particular, our findings indicate that pregnant young women and their male partners categorized in the perpetrator-victim classes were more likely to report IPV victimization in their current relationship. Dual involvement in violence as both a victim and perpetrator is intricate (Hamby & Grych, 2013) and several mechanisms and theories such as the social learning theory may postulate why pregnant young women and their partners are dually involved in violence. Our results provide evidence for the need to screen couples for violence across multiple domains in adolescent-friendly settings including prenatal care settings and to integrate violence-related services in adolescent pregnancy and parenting programs. Understanding that one’s experiences and engagement in violence across domains can influence one’s IPV experience in a current relationship may be one step toward improving the wellbeing of pregnant young couples.

Our findings highlight very distinct classes or subgroups of young women and men expecting a baby. Three subgroups of young women emerged: a group with no victimization experiences or engagement in perpetration (i.e., Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator), a victim-only group (i.e., Community Victim and Prior IPV), and a perpetrator-victim group (i.e., Polyvictim-Polyperpetrator). The Community Victim and Prior IPV class is consistent with previous research indicating that young mothers are at risk for IPV (Harrykissoon et al., 2002) and community violence (Kennedy, 2006). However, although a low prevalence, our finding of the Polyvictim-Polyperpetrator class, a group of young women who experienced prior IPV and family violence in addition to using violence against prior intimate partners, family, community members, and peers, extends previous research by highlighting that a co-occurrence of victimization and perpetration occurs among young pregnant women. Although young women have been shown in other studies as perpetrator-victims, acknowledging this co-occurrence will aid in the development of violence interventions (Hamby & Grych, 2013), especially among young pregnant women. Moreover, four subgroups emerged for young men: a group with no victimization experiences or engagement in perpetration (i.e., Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator), two victim-only groups (i.e., Community and Prior IPV Victim and Prior IPV and Peer Victim), and a perpetrator-victim group (i.e., Nonpartner Perpetrator-Polyvictim). The identification of two victim-only groups (i.e., Community and Prior IPV Victim and Prior IPV and Peer Victim) for young men is consistent with other studies suggesting young men are more likely to experience polyvictimization given the high prevalence of community and peer violence victimization experienced by young men (Ford et al., 2010; Hamby & Grych, 2013; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2010). Extending this research, our findings demonstrate that young men expecting a baby also report experiencing IPV in a past relationship because this type of violence was present in both victim-only groups. Similar yet meaningfully different than the young women’s perpetrator-victim group, the young men’s Nonpartner Perpetrator-Polyvictim class composed of young men who experienced violence from family, prior intimate partners, community members, peers in addition to using aggression toward family, community members, and peers. This finding is consistent with research among nonexpecting young men, finding young men likely to report being polyperpetrators and polyvictims (Hamby & Grych, 2013; Turner et al., 2010). Concurrently, the young men’s latent classes expand previous research by suggesting that prior IPV perpetration and polyperpetration only may not be a highly probable pattern of perpetration for young men expecting a baby because none of the young men’s latent classes had a high probability of prior IPV perpetration or only engagement in perpetration. Collectively, young women and men expecting a baby have diverse experiences with violence, which may influence their health and behaviors. Therefore, additional research is needed to understand and examine how health (e.g., depressive symptoms) and behaviors (e.g., parenting competence) of these potential subgroups differ.

The perpetrator-victim subgroups for both young women and men were more likely to report IPV experiences with the current partner. Previous research indicates that adolescents who experience multiple forms of violence are at an increased risk for revictimization (Hamby, Finkelhor, Turner, & Ormrod, 2010). Although few studies have examined the role of perpetrator-victim among young pregnant women and their partners, our findings suggest that the actor effects of young women’s Polyvictim-Polyperpetrator class and the young men’s Nonpartner Perpetrator-Polyvictim class experienced IPV with their current partner compared to the Nonvictim-Nonperpetrator classes. Social learning theory provides one possible explanation for the heightened IPV risk among these subgroups. According to this theory, observations and experiences with violence as either the victim and/or perpetrator can lead to a tolerance or acceptance of violence in future relationships (Bandura & McClelland, 1977) and even an adoption of an internal working model that interpersonal couples (e.g., friend–friend) interact with one another using violence (McClellan & Killeen, 2000). Therefore, young pregnant women and their partners in the perpetrator-victim classes may have a high acceptance of violence in interpersonal interactions and possibly increasing their vulnerability to IPV with their current partner. Perpetrator-victims may have a greater risk of injury (Hamby & Grych, 2013; Whitaker, Haileyesus, Swahn, & Saltzman, 2007); thus, it is important for additional research to explore vulnerabilities to IPV that may be unique this subgroup of young pregnant women and men to inform primary IPV intervention development.

A partner’s latent class did not predict the actor’s IPV victimization experiences in the current relationship. This finding is inconsistent with previous research among adult populations (Fritz et al., 2012), indicating that a partner’s history of family violence influenced the couple’s IPV experiences. For pregnant young couples, one’s own latent class may be more related to IPV victimization in the current relationship than the latent class of one’s partner; however, these nonsignificant partner effects may reflect the unique risk profiles of the young couples in this study. In particular, a large proportion of the adolescent couples consisted of those with experiences and/or engagement in violence paired with a partner who did not have those experiences and engagement. Future studies examining actor–partner effects of latent class membership among pregnant young couples should investigate differences in other couple-level factors (e.g., relationship functioning) between couples with and without violence experiences and/or engagement.

Although our findings are novel, they must be interpreted in light of certain limitations. First, cross-sectional studies are commonly used to explore cumulative abuse experiences (Scott-Storey, 2011); however, the cross-sectional nature of the baseline data prevents any causal inferences to be deduced. Future studies should use longitudinal designs to examine the incidence of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration and how it changes over time for pregnant young couples. Second, extant polyvictimization research examined the different number of victimization incidents including indirect forms of victimization (e.g., witnessing), defining polyvictimization as the 10% most victimized adolescents (Finkelhor et al., 2007). Although other studies defined polyvictimization as experiencing two or more victimization categories (Pereda & Gallardo-Pujol, 2014), there are multiple ways to operationalize “cumulative abuse” and regardless of the terminology, studies consistently indicate that experiencing multiples of victimization is associated with poor health outcomes (Scott-Storey, 2011). For this article, interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration was operationalized and examined empirically using latent class analyses, finding patterns of cumulative abuse (Scott-Storey, 2011). This operationalization of interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration is helpful for identifying high-risk, pregnant young couples. Future research should use larger sample sizes to differentiate indicators by physical and sexual acts. Third, this study only included direct physical and sexual acts of violence and not emotional/psychological or indirect acts of violence, which may limit the number of potential classes. Future studies using LCA should include emotional/psychological and indirect acts of violence. Final, this study used self-report data for violence, and both male and female partners were asked to report IPV perpetration and victimization during pregnancy. It is possible that the prevalence of IPV perpetration and victimization could be underreported because of social desirability bias. The study was administered using audio, computer-assisted interviews, which reduces social desirability bias (Kissinger et al., 1999).

Clinical Implications

Pregnant young couples experience interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration, and distinct subgroups of young women and men were likely to experience IPV victimization in the current relationships. In clinical settings and interventions, it is important that interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration are assessed including IPV in prior relationships, community violence, family violence, and peer violence. Developing and incorporating comprehensive screening tools that identify interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration may help to identify these distinct subgroups of pregnant young couples at risk for IPV victimization. These at-risk couples can then be referred to IPV prevention interventions. Similarly, interventions targeting young couples should focus on multiple forms of violence victimization for both individuals within the couple, instead of IPV in insolation (Hamby et al., 2012). Parenting and other couple-based interventions targeting interpersonal polyvictimization may help pregnant young couples transition into parenthood safely and with a reduced risk of IPV victimization. Understanding that pregnant young couple’s individual involvement with interpersonal polyvictimization and polyperpetration can influence the continuation of violence in their lives is essential to devising effective preventive methods.

Contributor Information

Tiara C. Willie, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Yale Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, New Haven, Connecticut.

Adeya Powell, Yale Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, New Haven, Connecticut.

Jessica Lewis, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Yale Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, New Haven, Connecticut.

Tamora Callands, Department of Health Promotion and Behavior, University of Georgia, Athens.

Trace Kershaw, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Yale Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, New Haven, Connecticut.

References

- Adams ZW, Moreland A, Cohen JR, Lee RC, Hanson RF, Danielson CK, Briggs EC. Polyvictimization: Latent profiles and mental health outcomes in a clinical sample of adolescents. Psychology of Violence. 2016;6:145–155. doi: 10.1037/a0039713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansara DL, Hindin MJ. Exploring gender differences in the patterns of intimate partner violence in Canada: A latent class approach. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2010;64:849–854. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.095208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, McClelland DC. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Celeux G, Soromenho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification. 1996;13(2):195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cole J, Logan T, Shannon L. Women’s risk for revictimization by a new abusive partner: For what should we be looking? Violence and Victims. 2008;23(3):315–330. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas CA, Sabina C, Bell KA. Dating violence and interpersonal victimization among a national sample of Latino youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55:564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas CA, Sabina C, Picard EH. Interpersonal victimization patterns and psychopathology among Latino women: Results from the SALAS study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2(4):296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2007;31(1):7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2009;33(7):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, Frueh BC. Poly-victimization and risk of post-traumatic, depressive, and substance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(6):545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Wasser T, Connor DF. Identifying and determining the symptom severity associated with polyvictimization among psychiatrically impaired children in the outpatient setting. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16(3):216–226. doi: 10.1177/1077559511406109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Linder GF, Bauman KE, Langwick SA, Arriaga XB, Heath JL, Bangdiwala S. The Safe Dates Project: Theoretical basis, evaluation design, and selected baseline findings. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz PAT, Slep AMS, O’Leary KD. Couple-level analysis of the relation between family-of-origin aggression and intimate partner violence. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2(2):139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian JA, Adams MM, Saltzman LE, Johnson CH, Bruce FC, Marks JS, Group PW. The relationship between pregnancy intendedness and physical violence in mothers of newborns. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;85(6):1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson C, Callands TA, Magriples U, Divney A, Kershaw T. Intimate partner violence, power, and equity among adolescent parents: Relation to child outcomes and parenting. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2015;19(1):188–195. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1509-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Coble CN, Latham L, Layman MJ. Sexual assault experience in adulthood and prior victimization experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1993;17(2):151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Haegerich TM, Massetti GM. Commentary on subgroup analysis in intervention research: Opportunities for the public health approach to violence prevention. Prevention Science. 2013;14(2):193–198. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R. The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimizations in a nationally representative survey of youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(10):734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Turner H. Teen dating violence: Co-occurrence with other victimizations in the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV) Psychology of Violence. 2012;2(2):111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, Grych J. The web of violence: Exploring connections among forms interpersonal violence and abuse. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harrykissoon SD, Rickert VI, Wiemann CM. Prevalence and patterns of intimate partner violence among adolescent mothers during the postpartum period. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(4):325–330. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Farhat T, Brooks-Russell A, Wang J, Barbieri B, Iannotti RJ. Dating violence perpetration and victimization among U. S. adolescents: Prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53(2):194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman LJ, Jaycox LH, Setodji CM, Kofner A, Schultz D, Barnes-Proby D, Harris R. How much does “how much” matter? Assessing the relationship between children’s lifetime exposure to violence and trauma symptoms, behavior problems, and parenting stress. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28(6):1338–1362. doi: 10.1177/0886260512468239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AC. Urban adolescent mothers exposed to community, family, and partner violence: Prevalence, outcomes, and welfare policy implications. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(1):44–54. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw T, Murphy A, Divney A, Magriples U, Niccolai L, Gordon D. What’s love got to do with it: Relationship functioning and mental and physical quality of life among pregnant adolescent couples. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;52(3–4):288–301. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9594-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsfogel KM, Grych JH. Interparental conflict and adolescent dating relationships: Integrating cognitive, emotional, and peer influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(3):505–515. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger P, Rice J, Farley T, Trim S, Jewitt K, Margavio V, Martin DH. Application of computer-assisted interviews to sexual behavior research. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;149(10):950–954. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50(3):455. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Capaldi DM. Clearly we’ve only just begun: Developing effective prevention programs for intimate partner violence. Prevention Science. 2012;13:410–414. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares LO, Heeren T, Bronfman E, Zuckerman B, Augustyn M, Tronick E. A mediational model for the impact of exposure to community violence on early child behavior problems. Child Development. 2001;72(2):639–652. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of partner abuse: A prospective-longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(3):375–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz FE. Attitudes and family violence: Linking intergenerational and cultural theories. Journal of Family Violence. 2001;16(2):205–218. [Google Scholar]

- McClellan AC, Killeen MR. Attachment theory and violence toward women by male intimate partners. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2000;32(4):353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon AL. Latent class analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, Levenson RR, Waldman J, Silverman JG. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Myint-U A. Parenting and violence toward self, partners, and others among inner-city young adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2255. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Myint-U A, Duran R, Agronick G, Wilson-Simmons R. Middle school aggression and subsequent intimate partner physical violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(5):693–703. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Slep AMS. Prevention of partner violence by focusing on behaviors of both young males and females. Prevention Science. 2012;13(4):329–339. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offenhauer P, Buchalter A. Teen dating violence: A literature review and annotated bibliography. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda N, Gallardo-Pujol D. One hit makes the difference: The role of polyvictimization in childhood in lifetime revictimization on a southern European sample. Violence and Victims. 2014;29(2):217–231. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00061r1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Houry D, Cerulli C, Straus H, Kaslow NJ, McNutt L-A. Intimate partner violence and comorbid mental health conditions among urban male patients. Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7(1):47–55. doi: 10.1370/afm.936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Storey K. Cumulative abuse: Do things add up? An evaluation of the conceptualization, operationalization, and methodological approaches in the study of the phenomenon of cumulative abuse. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2011;12:135–150. doi: 10.1177/1524838011404253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Greenman SJ, Thornberry TP, Henry KL, Ireland TO. Adolescent risk for intimate partner violence perpetration. Prevention Science. 2015;16:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0560-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler L, Paretilla C, Kirchner T, Forns M. Effects of poly-victimization on self-esteem and post-traumatic stress symptoms in Spanish adolescents. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;21(11):645–653. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby S, Warren W. The Conflict Tactics Scales handbook: Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2) and CTS: Parent-Child Version (CTSPC) Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(3):323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Hamby S. Recent victimization exposure and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166(12):1149–1154. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Shattuck A, Finkelhor D, Hamby S. Polyvictimization and youth violence exposure across contexts. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;58:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, Saltzman LS. Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(5):941–947. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside LK, Ranney ML, Chermack ST, Zimmerman MA, Cunningham RM, Walton MA. The overlap of youth violence among aggressive adolescents with past-year alcohol use—a latent class analysis: Aggression and victimization in peer and dating violence in an inner city emergency department sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(1):125–135. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie TC, Powell A, Kershaw T. Stress in the city: Influence of urban social stress and violence on pregnancy and postpartum quality of life among adolescent and young mothers. Journal of Urban Health. 2016;93(1):19–35. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-0021-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]