Abstract

Tight ligand-receptor binding, paradoxically, is a major root of drug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. To address this problem, instead of using conventional inhibitors or ligands, we focus on the development of a novel process—enzyme-instructed self-assembly (EISA)—to kill cancer cells selectively. Here we demonstrate that EISA as an intracellular process to generate nanofibrils of short peptides for selectively inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, including drug resistant ones. As the process that turns the non-self-assembling precursors into the self-assembling peptides upon the catalysis of carboxylesterases (CES), EISA occurs intracellularly to selectively inhibit a range of cancer cells that exhibit relatively high CES activities. More importantly, EISA inhibits drug resistant cancer cells (e.g., triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells (HCC1937) and platinum-resistant ovarian cells (SKOV3, A2780cis)). With the IC50 values of 28–80 μg/mL and 25–44 μg/mL of L- and D-dipeptide precursors against cancer cells, respectively, EISA is innocuous to normal cells. Moreover, using co-culture of cancer and normal cells, we validate the selectivity of EISA against cancer cells. Besides revealing that intracellular EISA cause apoptosis or necroptosis to kill the cancer cells, this work illustrates a new approach to amplify the enzymatic difference between cancer and normal cells and to expand the pool of drug candidates for potentially overcoming drug resistance in cancer therapy.

Keywords: enzyme, self-assembly, selectivity, anticancer, drug-resistance

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

This article reports that carboxylesterases (CES) convert non-self-assembling precursors into self-assembling peptides that form intracellular nanofibrils to selectively inhibit cancer cells. Due to genomic instability, cancers usually evolve to drug resistant tumors and results in high mortality.[1] Targeting a specific protein or nucleic acid or a critical enzyme, molecular therapy has made significant progresses in the last two decades. However, largely due to the almost inevitable relapse in the patients with advanced cancers to develop drug resistance, chemotherapy and molecular therapy are still unable to meet all the need of cancer therapy, particularly in cancers that are still lack of immunotherapy. For example, due to the low level expression of cancer specific antigens (e.g., PD-L1)[2] or the presence of other immunosuppressive mechanism,[3] considerable types of cancers (e.g., glioma and ovarian adenocarcinoma) respond poorly to cancer immunotherapy.[4] Thus, there is urgent need of a new approach for addressing such a gap in cancer therapy[5].

Being evolved from supramolecular chemistry,[6] especially supramolecular gels[7] and hydrogels[7–8], enzyme-instructed self-assembly (EISA), that is, the integration of enzymatic catalysis and molecular self-assembly, has emerging as a multiple step process for selectively inducing cancer cell death.[9] We have been working on the application of EISA inside cells,[9a, 10] as well as in pericellular space,[9b] for inducing cancer cell death selectively.[11] Our works on nanofibrils of small peptides also reveal that the promiscuous interactions between the nanofibrils and cytoskeleton proteins (e.g., actins) lead to selective inhibition of cancer in cell assay[12] and in animal model.[9b] Wells et al. reported the self-assembly of small molecules into nanofibrils that can cause cell death via multiple mechanisms.[13] Recently, Maruyama et al.,[14] Pires and Ulijn,[8c] and Yang et al.,[8g, 15] also reported inhibition cancer cells by supramolecular nanofibrils generated by EISA. Gao and co-workers reported the use of phosphatase-based EISA for cancer theranostics in a mice model.[16] Most recently, we demonstrated that intracellular nanofibrils formed by EISA are able to enhance the activity of cisplatin against platinum resistant ovarian cancer cells.[17] Despite these exciting and promising progresses of EISA, the need of cisplatin remains a limitation because of the poor selectivity cisplatin itself. In addition, the relevant modality of cell death caused by the intracellular nanofibrils has yet to be determined.

The exceptional selectivity[18] and fundamentally new mechanisms[9b, 12] of EISA, as a process, against cancer cells encouraged us to further develop EISA for inhibiting cancer cell proliferation. Encouraged by the development of prodrugs based on CES [19], we explore CES-based EISA for inducing cancer cell death. CES, a kind of esterase found in human organ and tissues, serves an important role in hydrolyzing esters. The installation of ester bond in the prodrugs can help improve the lipophilicity, selectivity, solubility and other properties of the parent drugs.[20] Among all the marketed prodrugs, about half of them are esters that require the activation by esterases. For example, CPT-11 is an anticancer prodrug with better aqueous solubility, which can be converted into its active metabolite SN-38 by CES with enhanced cytotoxicity.[19b] Despite it consists of the step of enzymatic transformation, EISA differs from the prodrug approach[19c, 21] because only the supramolecular assemblies, not the monomeric, un-assembled products of the enzymatic conversion, are inhibitory to cancer cells.[9b, c]

We decide to examine the correlation of the activities of CES and the inhibition efficacy of EISA in a range of cancer cells. Specifically, we explore EISA of a pair of enantiomeric dipeptide and taurine conjugates (L- and D-DPT) installed with ester bond between the dipeptides[12] and taurine[22] for inhibiting drug resistant cancer cells. We develop the non-self-assembling precursors (i.e., the conjugates, L- or D-DPT) that turn into the self-assembling molecules (i.e., the dipeptides, L- or D-DP) upon intracellular hydrolysis catalyzed by CES. We find that the precursors selectively inhibit cancer cells (e.g., HCC1937, MCF-7, SKOV3, A2780, A2780cis, HeLa, MES-SA and Saos-2) without inducing death of normal cells (e.g., stromal cells HS-5). The inhibitory activities of the precursors correlate with the activities of the CES of the cells. Our results confirm that the overexpression of CES in cancer cells is responsible for selective inhibition of the cancer cells by the EISA of the dipeptides. Our study also reveals that the formation of the intracellular nanofibrils disrupts the dynamics of actin filament to cause either apoptosis or necroptosis of the cancer cells[17] (Figure 1, Figure S1, and Figure S2). Moreover, D-DPT always exhibit higher inhibitory activities than the L-DPT, agreeing with the proteolytic stability of D-DPT and D-DP. By establishing intracellular EISA for selectively inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, this work illustrates a new approach that relies on enzymatic reaction (not on enzyme inhibition) to amplify the difference between cancer and normal cells for selectively killing the cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Illustration of intracellular EISA to inhibit cancer cells and the molecular structure of the precursors and the corresponding self-assembling molecules.

2. Results and discussion

We design and synthesize an enantiomeric pair of N-terminal capped diphenylalanine that conjugates with taurine as the precursors (i.e., L- or D-DPT). After the hydrolytically removal of the taurine moiety by an esterase, the corresponding products, dipeptides (i.e., L- or D-DP), self-assemble in water to form nanofibrils. Both the precursors and the dipeptides can be easily made in large quantities by a facile synthetic route that combines liquid phase synthesis and solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS). In this design, naphthyl capped diphenylalanine (NapFF) [23] serves as the self-assembly motif to provide aromatic-aromatic interactions for enhancing intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the dipeptides in water. With the installed ester bond linked taurine on the precursors, CES can convert the non-self-assembling precursors (L- or D-DPT) to self-assembling dipeptide derivatives (L- or D-DP), which self-assemble to form nanofibrils.[17] We choose to test an enantiomeric pair because the biostability of the dipeptides in cellular environment is an important aspect of pharmacokinetics. Particularly, the enantiomer composed by D-amino acids (D-DPT) can resist the degradation of endogenous proteases, thus warrants the long term function of the self-assembled peptide nanofibrils. Beside the difference in proteolytic stability of each peptide, self-assembly kinetics of the peptides could also be different, which cause the difference in efficacy. However, since L-DPT and D-DPT exhibit similar hydrolysis rates (Figure S3) upon the addition of esterase (0.1 U/mL), proteolytic stability likely would be the major factor. After the synthesis of L-DPT and D-DPT, we purify the crude compounds by HPLC and characterize the purified compounds by NMR and LC-MS.[17] It is relatively easy to produce gram quantity of these derivatized dipeptides.

2.1. Inhibitory activities of the precursors on multiple cell lines

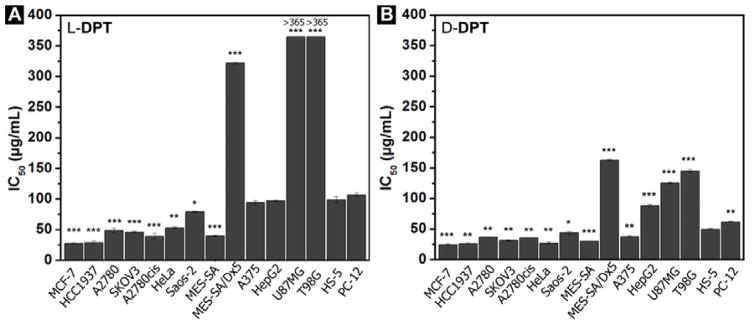

After obtaining the precursors, we test the cytotoxicity of L-DPT (or D-DPT) on multiple cell lines including cancer cells and normal cells (Figure 2) and summarize the IC50 values of the third day (i.e., 72 h) in μg/mL (Figure 3A and 3B). We test the precursors on two breast cancer cell lines—HCC1937, a line of triple negative breast cancer cells (TNBC), and MCF-7, a common breast cancer cell line. As summarized in Figure 2, Figure 3A and 3B, L-DPT and D-DPT are very effective against these two cell lines. The IC50 values of L-DPT for HCC1937 and MCF-7 are 29 and 28 μg/mL, respectively; the IC50 values of D-DPT for HCC1937 and MCF-7 are 26 and 25 μg/mL, respectively. Being incubated with a drug sensitive (A2780) and two platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cell lines (A2780cis and SKOV3), L-DPT gives the IC50 values of 49, 39 and 46 μg/mL against A2780, A2780cis, and SKOV3, respectively. Similar to the case of inducing cell death of breast cancer cells, D-DPT exhibits higher inhibitory activity than L-DPT, with IC50 values at 37, 36 and 31 μg/mL, respectively, against those three cell lines. Notably, both precursors (i.e., L- and D-DPT) are slightly more inhibitive towards SKOV3 cells, which is a platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cells, than towards A2780 cells (a cell line is sensitive to cisplatin). Moreover, A2780 and A2780cis exhibit similar susceptibilities to either L- DPT or D-DPT, indicating the efflux pumps of A2780cis, which cause the platinum resistance, unlikely are able to pump out the nanofibrils effectively. After being incubated with adenocarcinoma (HeLa) and osteosarcoma cells (Saos-2), D-DPT exhibits the IC50 values of 27 μg/mL and 44 μg/mL, respectively. In contrast, the IC50 values of L-DPT against HeLa and Saos-2 are 53 μg/mL and 80 μg/mL, respectively. We also test the cytotoxicity of L-DPT and D-DPT on drug sensitive (MES-SA) and drug resistant (MES-SA/Dx5) uterine sarcoma cells. Both L-DPT and D-DPT exhibit high inhibitory activities on MES-SA cells with IC50 values at 40 μg/mL and 31 μg/mL, respectively. However, both the L-DPT and D-DPT show lower cytotoxicity on MES-SA/Dx5 cells, with the IC50 values at 322 μg/mL and 163 μg/mL, respectively. The incubation of L-DPT on melanoma cancer cells (A375) and hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2) results in the IC50 values at 94 μg/mL and 97 μg/mL, respectively. D-DPT shows higher cytotoxicity, inducing cell death of A375 and HepG2 cells with and IC50 values of 38 μg/mL and 88 μg/mL, respectively. The insensitivity of HepG2 to L-DPT and D-DPT suggests that L-DPT and D-DPT may exhibit low in vivo toxicity to liver functions since HepG2 often acts as a model cell of hepatocyte. This assumption is confirmed by in vivo toxicity examination (vide infra) in mice. Being tested on two glioblastoma cell line cell lines (U87MG and T98G), L-DPT shows little cytotoxicity toward these two cancer cell lines at or below concentration of 146 μg/mL. The cell viabilities of U87MG and T98G cells, after being treated by 365 μg/mL of L-DPT, are about 70% and 60%, respectively. D-DPT exhibits higher inhibitory activity towards to these two cell lines, with the IC50 values of 126 μg/mL and 145 μg/mL at 72 h incubation of U87MG and T98G, respectively. As a control experiment, we test the cytotoxicity of the precursors on two normal cell lines—HS-5, a stromal cell derived from normal bone marrow,[24] and PC12, a model neuron cell line from mice. Both L-DPT and D-DPT show little cytotoxicity on these two cell lines. The IC50 values of L-DPT on HS-5 and PC-12 are 99 μg/mL and 106 μg/mL, respectively, which are higher than the IC50 values of L-DPT on most of the cancer cell lines we tested. The IC50 values of D-DPT on HS-5 and PC-12 are 50 and 62 μg/mL, respectively, which are also two to three times higher than the IC50 values of D-DPT against most of the cancer cells tested.

Figure 2.

Cell viabilities of multiple cell lines incubated with L-DPT (black curve) or D-DPT (red curve) for 72 h. Cell viabilities of a triple negative breast cancer cell line (HCC1937), a breast cancer cell line (MCF-7), a drug sensitive ovarian cancer cell line (A2780), two drug resistant ovarian cancer cell lines (A2780cis and SKOV3), an adenocarcinoma cell line (HeLa), an osteosarcoma cell line (Saos-2), a drug sensitive sarcoma cell line (MES-SA), a drug resistant sarcoma cell line (MES-SA/Dx5), a melanoma cancer cell line (A375), a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2), two glioblastoma cell lines (U87MG and T98G),, a stromal cell line (HS-5) and a neuronal cell line (PC-12) are tested. 104 cells/well were initially seeded in a 96 well plate.

Figure 3.

Summary of IC50 values of A) L-DPT and B) D-DPT on multiple cell lines on the third day (* = p≤ 0.05, ** = p ≤ 0.01, *** = p ≤ 0.001 versus IC50 value of precursors on HS-5 cell).

To assess the selectivity of L-DPT and D-DPT towards cancer cells, we compare their activities on drug resistant ovarian cancer cells (A2780cis and SKOV3) and the stromal cells (HS-5) at about the IC90 of the inhibitors against the cancer cells. As shown in Figure 4A, L-DPT, at 73 μg/mL, shows high cytotoxicity on both A2780cis and SKOV3 cells (ovarian cancer cells) and inhibits almost 100% of the cancer cells on the third day. At the same concentration, L-DPT hardly inhibits the HS-5 cell (and the cell viability is about 80% on the third day). D-DPT also shows potent cytotoxicity towards ovarian cancer cells, especially to SKOV3 cells. D-DPT, at 37 μg/mL, inhibits more than 90% of SKOV3 cells and about 55% of A2780cis cells on the third day. Treated by D-DPT at 37 μg/mL, HS-5 cells exhibit about 80% viability at day three. These results confirm that the two precursors are able to selectively inhibit ovarian cancer cells at their IC90 with little inhibition to HS-5 cells. As another positive control, we test the cytotoxicity of cisplatin on those two ovarian cancer cell lines. Cisplatin, which is known as a powerful anticancer drug can inhibit 90% of SKOV3 cells and about 98% of A2780cis cells on the third day at concentration of 37 μg/mL. However, cisplatin (37 μg/mL) kills almost 100% of HS-5 on the third day. This result indicates the limitation of cisplatin, agreeing with that cisplatin has little selectivity and may cause high systematic toxicity to normal cells. Interestingly, L-DPT, at 37 μg/mL, is innocuous to those two ovarian cancer cells, as well as to normal cells. This result implies that the proteolytic instability of L-DPT in cellular environment likely contribute to its low cytotoxicity towards SKOV3 and A2780cis.

Figure 4.

A) Cell viabilities of the stromal cells (HS-5) and ovarian cancer cells (A2780cis and SKOV3) (104 cells/well were initially seeded in a 96 well plate) incubated with the precursor L-DPT (73 μg/mL), D-DPT (37 μg/mL), or CDDP (cisplatin) (37 μg/mL) for 3 days. B) Cell viabilities of the co-cultured SKOV3/HS-5 cells and A2780cis/HS-5 cells incubated with the precursor L-DPT (73 μg/mL) or D-DPT (37 μg/mL) for 3 days. 5000 of each co-cultured cells were initially seeded in a 96 well plate.

2.2. Cytotoxicity of EISA on co-cultured cells

To further verify that intracellular EISA selectively inhibits cancer cells, we co-culture the stromal cells (HS-5) cells together with the drug resistant ovarian cancer cells (SKOV3 or A2780cis cells). We seed 5×103 of SKOV3 cells (or A2780cis) and 5×103 HS-5 cells per well together and co-culture them in DMEM medium. Based on the results in Figure 4A, we choose to use the concentrations of L-DPT and D-DPT at 73 and 37 μg/mL, respectively. As shown in Figure 4B, precursor L-DPT at 73 μg/mL shows cytotoxicity to the co-cultured HS-5 and SKOV3 cells, which causes about 60% of cell death on the third day. The efficacy of L-DPT (73 μg/mL) on co-cultured HS-5 and A2780cis cells is comparable to its efficacy on co-cultured HS-5 and SKOV3 cells as it inhibits about 57% of cells on the third day. As shown in Figure 4A, cancer cells (SKOV3, A2780cis) were inhibited almost by 100% on the third day after the treatment of the same concentrations of L-DPT (73 μg/mL) while normal cells are almost all alive, which agrees well with the co-cultured results. We use D-DPT (37 μg/mL) to treat the co-cultured cells and find that the inhibitory activity of D-DPT increases when we extend the incubation time to day three. For example, on the first day, the cell viabilities of co-cultured HS-5 and SKOV3 cells and co-cultured HS-5 and A2780cis cells treated by D-DPT (37 μg/mL) are 79% and 80%, respectively. While on the third day, the cell viabilities drop to 44% and 57%, respectively. In addition, after being treated by the same concentration of D-DPT (37 μg/mL) for three days, 90% of SKOV3 cells and 60% of A2780cis cells are killed while about 80% of HS-5 cells are still viable (Figure 4A). D-DPT (37 μg/mL) shows higher cytotoxicity to co-cultured HS-5 and SKOV3 cells than co-cultured HS-5 and A2780cis cells, which is consistent with the respective cytotoxicities of D-DPT against only SKOV3 or only A2780cis cells. Contrary to the case of D-DPT, the efficacies of L-DPT are almost the same between day two and day three (Figure 4B), which agrees with the lower in vivo stability of L-DPT than that of D-DPT. In summary, the inhibitory activities of L-DPT and D-DPT towards the co-culture agree well with their respective cytotoxicity against A2780cis, SKOV3, and H-5 cells in the culture of each cell line, indicating that the precursors could selectively inhibit cancer cells in the co-culture. We also co-culture HeLa-GFP cells together with HS-5 cells (5×104 each) and treat the co-cultured cells with L-DPT (73 μg/mL), D-DPT (37 μg/mL) or culture medium (control) for 30 h. Green fluorescence indicates HeLa-GFP cells and blue fluorescence represents all kinds of cells. As shown in Figure S4, in the control group, both green and blue fluorescence exists, which indicates that both GFP-HeLa and HS-5 cells are alive. After being treated by L-DPT or D-DPT, HeLa-GFP cells are dead (no green fluorescence), while blue fluorescence indicates that HS-5 are still alive. This experiment confirms that the precursors selectively induce cancer cell deaths.

2.3. Quantification of esterase activities in multiple cell lines

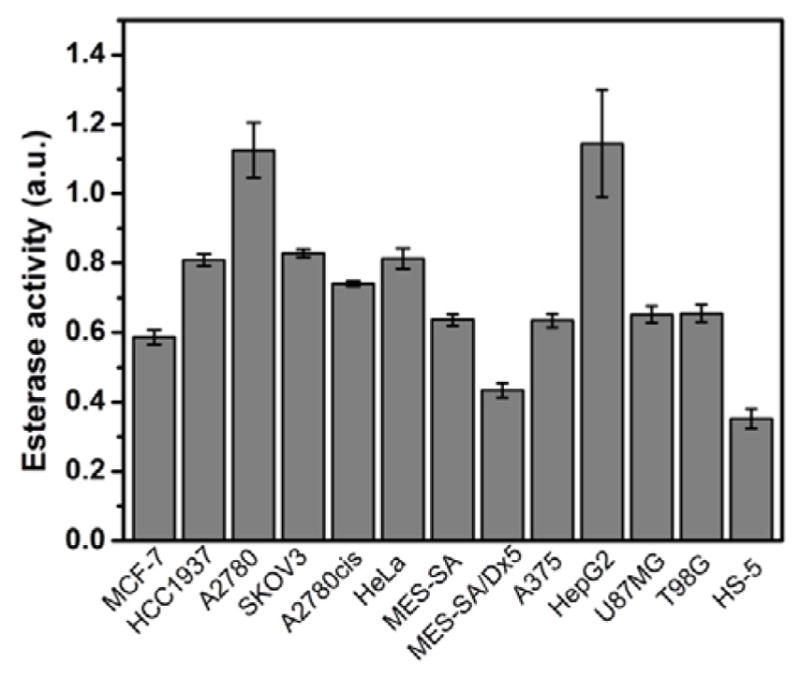

To evaluate the contribution of the expression of CES for the observed selectivity against the cancer cells, we quantify the esterase activities in those cell lines (Figure 5). Using 6-CFDA (6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate) as the substrate of esterase, we measure the fluorescence upon the hydrolysis by intracellular esterases. For the comparison, we divide the intensity of the measured fluorescence by the total cellular proteins (fluorescence per pg protein) of each cell line. HepG2 and A2780 show relatively high esterase activity among the tested cell lines, with values larger than 1. HCC1937, SKOV3 and HeLa cells show similar esterase activities, which are higher than 0.8. A2780cis cells have an esterase activity value higher than 0.7 and U87MG, T98G, A375, MES-SA and MCF-7 cells have values around 0.6. MES-SA/Dx5 cells have very low esterase activity value at about 0.4. HS-5 cells have the lowest esterase activity (about 0.35) among all the cell lines tested. The trend of the esterase activity largely matches the cytotoxicity results shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. For example, both the precursors show low cytotoxicity to HS-5 cells and MES-SA/Dx5 cells, which have low esterase activity values. The precursors show high cytotoxicity to A2780, HCC1937, SKOV3, HeLa and A2780cis cells, which have comparably high esterase activity values, which confirm that CES plays a key role in selectively inhibiting cancer cell proliferation by EISA. As shown in Figure S5, except for HepG2, U87MG and T98G, the precursor shows high cytotoxicity (i.e., low IC50 values) to the cells that exhibit high esterase activities. Although normal cells also exhibit esterase activity, which is two to four times lower than the esterase activities in cancer cells. The much lower esterase activity in normal cells results in slow conversion of the precursors inside the cells so that the precursors show lower toxicity to normal cells than to the cancer cells. We treat HeLa cell, HS-5 cells and HOSE-636 cell (human ovarian surface epithelium) with D-DPT at 37 μg/mL or L-DPT at 73 μg/mL for 12h, and then we stain the cell with Congo red (a dye to indicate the formation of nanofibers) and Hoechst (nuclei). As shown in Figures S6, and S7, S8, HeLa cells treated with the precursors show bright red fluorescence, which indicates the formation of nanofibers inside cells. However, both HS-5 and HOSE-636 show little red fluorescence. These results confirm that there are more nanofibers formed inside cancer cells than in normal cells. We also summarize the substrate fluorescence versus total cell number (Figure S9). The general trend is similar to the result obtained by normalizing to the total protein amount, and that normal cell (HS-5) still has the lowest amount of esterase.

Figure 5.

Summary of the quantification of esterase activities in multiple cell lines.

2.4. Determination of the modality of cell death

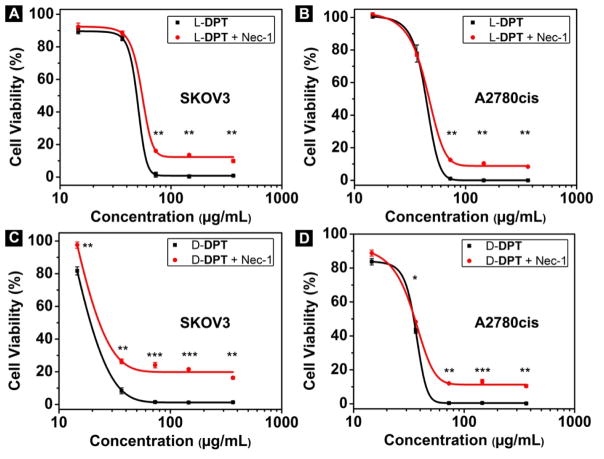

In order to determine the modality of cell death[25] caused by intracellular EISA, we use the pan caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk,[26] which is an anti-apoptotic agent that can inhibit caspase activities, to treat the cancer cells together with L-DPT and D-DPT to test the roles of caspases in the cell death process. As shown in Figure 6A and 6B, there is hardly obvious difference with and without the addition of zVAD-fmk (45 μM) into the L-DPT treated SKOV3 or A2780cis cells. This result indicates that EISA of L-DPT causes death of SKOV3 or A2780cis via caspase-independent mechanism.[27] Contrasting to the case of L-DPT, the addition of zVAD-fmk (45 μM) significantly increases the viability of the SKOV3 cell treated the D-DPT (37 μg/mL) from 10% to 77% (Figure 6C), indicating apoptotic dependence at that concentration. This observation suggests the mechanism of cell death depends on the concentrations of L-DPT (or D-DPT), which agrees with the notion of EISA. However, zVAD-fmk hardly increases the cell viability when 73 μg/mL of D-DPT treats the SKOV3 cells. While D-DPT at 37 μg/mL largely leads to apoptosis, D-DPT at 73 μg/mL apparently causes caspase independent cell death of SKOV3. These results suggest that the modality of cell death of SKOV3 depends on the amount of intracellular nanofibrils of D-DP formed by EISA. In the case of A2780cis cells treated by D-DPT at 37 μg/mL, the addition of zVAD-fmk results in only insignificantly increase (10%) cell viability (Figure 6D), suggesting that apoptosis unlikely is the major cause of the death of A2780cis cell. Nec-1 (Necrostatin-1),[28] which is an inhibitor of necroptosis, a mechanism of programmed cell death different from apoptosis, is also used to treat the cancer cells. As shown in Figure 7A, SKOV3 cells with the treatment of 50 μM of Nec-1 together with L-DPT at or above 73 μg/mL show slightly higher cell viability (about 15%) comparing with the cells treated by L-DPT alone. The difference between the cell viabilities of A2780cis cells treated with L-DPT alone and the combination of Nec-1 and L-DPT is insignificant either (10%) (Figure 7B). Similar trend is shown in the case of D-DPT that the difference with or without the addition of Nec-1 (50 μM) into D-DPT treated SKOV3 cells or A2780cis cells is about 20% or 13%, respectively (Figure 7C and 7D). The significant increase of the cell viability after the addition of Nec-1 indicates that necroptosis contributes to cell death but is unlikely the major cause of the death of SKOV3 cells and A2780cis cells as SKOV3 and A2780cis cell viabilities are unable to return to 100%. This observation indicates that cell death likely is resulted from multiple mechanisms.

Figure 6.

Cell viability of SKOV3 cells and A2780cis cells incubated with (A, B) L-DPT alone, or L-DPT + zVAD-fmk (45 μM); (C, D) D-DPT alone, or D-DPT + zVAD-fmk (45 μM) for 72 h (* = p≤ 0.05, ** = p ≤ 0.01, *** = p ≤ 0.001).

Figure 7.

Cell viability of SKOV3 cells and A2780cis cells incubated with (A, B) L-DPT alone, or L-DPT + Nec-1 (50 μM); (C, D) D-DPT alone, or D-DPT +Nec-1 (50 μM) for 72 h (* = p≤ 0.05, ** = p ≤ 0.01, *** = p ≤ 0.001).

2.5. In vivo toxicity of the precursors of EISA

To further validate that the precursors are non-toxic to normal tissues, we test the in vivo toxicity of the precursors in mice. As shown in Figure S10A, the body weights of mice treated with PBS buffer or L-DPT at concentrations of 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg are statistically same, indicating that L-DPT hardly cause obvious adverse effects on the growth of mice. Figure S10B and S10C show the calculated thymus and spleen indexes, which reflex the immune response of mice to the precursor L-DPT. The difference between the control group (PBS buffer) and L-DPT group is insignificant, indicating that the intravenous injection of the precursors unlikely causes immune response of mice. Figure S10D shows the hematology results, including the values of white blood cells (WBC), red blood cells (RBC), hematocrit (HCT), hemoglobin (HGB), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) and platelet (PLT). There are no significant differences observed between the control group and L-DPT group on all the standard markers of hematology detected in the study. This result confirms that L-DPT hardly induces inflammatory responses in major organs even at a dosage of 20 mg/kg. Furthermore, we also examine the blood biochemistry indicators such as alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), albumin (ALB), total protein (TP), total bilirubin (TBIL), creatinine (CRE), urea (UA) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) to analyse the influence of L-DPT on the liver and kidney functions of mice (Figure S10E). These indicators confirm that L-DPT is innocuous on the liver and kidney functions of mice. Same in vivo toxicity study are carried out with D-DPT at the same dosages, which show similar results (Figure S11). Besides, H&E staining results shown in Figure S12 indicate that, comparing with the control group, no apparent histopathological abnormalities can be observed for the groups treated with the precursors L-DPT and D-DPT. To summarise, both the precursors show no in vivo toxicity to mice at the dosage of 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg and cause no obvious tissue dysfunction or damage, immune response, and inflammatory response.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, by establishing cytosolic enzymes-instructed self-assembly as an anticancer process, this work illustrates a fundamentally new approach to amplify the enzymatic difference between cancer and normal cells for overcoming cancer drug resistance. Although we demonstrated that EISA of dipeptides can selectively inhibit a range of cancer cells, other molecules that are prone to self-assembly or aggregate in water[29] may serve as the candidates for developing EISA. Because the precursors exhibit much higher inhibitory activity to cancer cells (e.g., HCC1937, MCF-7, SKOV3) than to normal cells (HS-5), this study provides a new direction for developing anticancer therapies. In vivo toxicity results further validate that the precursors are innocuous to normal tissues and hardly cause inflammatory response and immune response. The activities of CES in different cell lines correlate to the inhibitory activity of the precursors on these cell lines. For example, the precursors show high inhibition on the cancer cells, which have higher expression of CES such as HCC1937, A2780 and SKOV3. Although normal cells still have some esterase activity, L-DPT and D-DPT are largely innocuous to normal cells (e.g., PC12) over 7 days (Figure S13). This result suggests that the rate of EISA controls cell fate. Besides, we also discover that the precursors (L-DPT and D-DPT) show higher inhibitions on SKOV3 cells (platinum-resistant cell line) than on A2780 cells (platinum sensitive cell line), which reveals that the precursors inhibit drug resistant cancer cells with high activity. Our study reveals that U87MG, T98G, and MES-SA/Dx5 are insensitive to intracellular EISA, which warrants to explore different approaches, such as pericellular EISA of small peptides[9b] or combination therapy[17], for selectively inhibiting those cancer cells. Moreover, considering the fundament difference between EISA and the conventional prodrug approach, we envision that EISA ultimately may lead to a new therapy, which uses enzyme controlled dynamics of self-assembly of other molecules[30] or entities[31], for detecting and treating cancers. Although the esterase activity in extracellular space may decrease the in vivo efficacy of the precursors by prematurely hydrolyzing the precursors, it is possible to use a cell-impermeable esterase inhibitor together with the precursors for selectively targeting cancer cells in vivo, which is part of on-going research.

4. Experimental Section

Reagents

The reagents used such as N, N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), O-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium-hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), and taurine were purchased from ACROS Organics USA. All other amino acid derivatives were purchased from GL Biochem (Shanghai) Ltd. The synthesis of L-DPT and D-DPT have been reported previously[17] so it is only described briefly here. We combine the liquid phase synthesis and solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) together for synthesizing L-DPT and D-DPT and the crude compounds are purified by HPLC with an overall yield at about 60%.

Cell culture

All cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Cells are seeded in the density of 104 cells/well in 96 well plates. U87MG, T98G, HepG2, HeLa and MCF-7 cells are maintained in MEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. A375 and HS-5 cells are maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. MES-SA, MES-SA/Dx5 and SKOV3 cells are maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium modified supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. A2780, A2780cis and HCC1937 cells are maintained in PRMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Saos-2 cells are maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium modified supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. PC12 cells are maintained in F-12K supplemented with 10% horse serum, 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). All cells are grown at 37 ºC, 5% CO2.

MTT assay

According to previously reported procedure,[32] we examine cell viability by MTT assay.

Measurement of esterase activity

80 μL of 6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate (25 μM in PBS buffer) is used to stain cells in each well. After incubation at 37 ºC in dark for 30 minutes, the fluorescence of each well is determined by microplate reader equipped with 485 nm excitation and 535 nm emission filter. The esterase activity values are calculated by using the fluorescence units got from the plate reader divided by cell protein weight (pg) per well.

In vivo toxicity

Mice were randomly divided into 7 groups: PBS buffer, L-DPT at 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, and 20 mg/kg, respectively, D-DPT at 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, and 20 mg/kg, respectively. Each group includes 12 mice and 4 mice per time point (day 1, day 4 and day 7). L-DPT and D-DPT were dissolved in 100 μL PBS buffer to achieve the above mentioned concentrations. PBS buffer or the diluted samples was administrated via the tail vein for one administration. Mice body weights were monitored every day for 7 days since the administration. Thymus and spleen were harvested on day 1, day 4 and day 7 to study the immune response of mice. Hematological and biochemical analysis were performed on day 1, day 4 and day 7 by automatic blood analyzer using whole blood samples collected from eyes at the designated time points. Haematoxylin & eosin (H&E) assays were performed using the heart, liver, kidney, lung and spleen harvested on day 7.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NIH (R01CA142746). JZ is a HHMI international research fellow.

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author. Results of in vivo toxicity of L-DPT and D-DPT, Haematoxylin & eosin (H&E) stained tissue slices from mice treated with PBS buffer, L-DPT or D-DPT are included in the supporting information.

Contributor Information

Prof. Jie Li, Department of Chemistry, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454, USA

Junfeng Shi, Department of Chemistry, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454, USA.

Jamie E. Medina, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115 (USA)

Jie Zhou, Department of Chemistry, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454, USA.

Xuewen Du, Department of Chemistry, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454, USA.

Huaimin Wang, Department of Chemistry, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454, USA. State Key Laboratory of Medicinal Chemical Biology and College of Life Sciences, Nankai University, Tianjin, 300071, China.

Cuihong Yang, Chinese Academy of Medical Science & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300192, China.

Jianfeng Liu, Chinese Academy of Medical Science & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin 300192, China.

Prof. Zhimou Yang, State Key Laboratory of Medicinal Chemical Biology and College of Life Sciences, Nankai University, Tianjin, 300071, China

Prof. Daniela M. Dinulescu, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115 (USA)

Prof. Bing Xu, Prof. Department of Chemistry, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454, USA

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Cell. 2011;144:646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong HD, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, Roche PC, Lu J, Zhu GF, Tamada K, Lennon VA, Celis E, Chen LP. Nat Med. 2002;8:793. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Virgilio F, Vuerich M. Auton Neurosci-basic. 2015;191:117. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Wilczyński JR, Nowak M. Cancer Immunology. Springer; 2015. p. 413. [Google Scholar]; b) Adams SF, Benencia F. Future Oncol. 2015;11:1293. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bisikirska B, Bansal M, Shen Y, Teruya-Feldstein J, Chaganti R, Califano A. Cancer Res. 2016;76:664. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehn J-M. Supramolecular Chemistry: Concepts and Perspectives. Wiley-VCH; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terech P, Weiss RG. Chem Rev. 1997;97:3133. doi: 10.1021/cr9700282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Cheetham AG, Zhang P, Lin Y-a, Lock LL, Cui H. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2907. doi: 10.1021/ja3115983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Newcomb CJ, Sur S, Ortony JH, Lee OS, Matson JB, Boekhoven J, Yu JM, Schatz GC, Stupp SI. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Pires RA, Abul-Haija YM, Costa DS, Novoa-Carballal R, Reis RL, Ulijn RV, Pashkuleva I. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:576. doi: 10.1021/ja5111893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Pochan DJ, Schneider JP, Kretsinger J, Ozbas B, Rajagopal K, Haines L. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11802. doi: 10.1021/ja0353154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Schneider JP, Pochan DJ, Ozbas B, Rajagopal K, Pakstis L, Kretsinger J. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:15030. doi: 10.1021/ja027993g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Yamanaka M, Kawaharada M, Nito Y, Takaya H, Kobayashi K. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16650. doi: 10.1021/ja207092c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Wang H, Yang Z. Soft Matter. 2012;8:2344. [Google Scholar]; h) Yoshii T, Mizusawa K, Takaoka Y, Hamachi I. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16635. doi: 10.1021/ja508955y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) He M, Li J, Tan S, Wang R, Zhang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:18718. doi: 10.1021/ja409000b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Li C, Numata M, Bae AH, Sakurai K, Shinkai S. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4548. doi: 10.1021/ja050168q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Woodward RT, Stevens LA, Dawson R, Vijayaraghavan M, Hasell T, Silverwood IP, Ewing AV, Ratvijitvech T, Exley JD, Chong SY, Blanc F, Adams DJ, Kazarian SG, Snape CE, Drage TC, Cooper AI. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9028. doi: 10.1021/ja5031968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Yang Z, Xu K, Guo Z, Guo Z, Xu B. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3152. [Google Scholar]; b) Kuang Y, Shi J, Li J, Yuan D, Alberti KA, Xu Q, Xu B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:8104. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhou J, Xu B. Bioconj Chem. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Gao Y, Kuang Y, Du X, Zhou J, Chandran P, Horkay F, Xu B. Langmuir. 2013;29:15191. doi: 10.1021/la403457c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang HM, Feng ZQQ, Wu DD, Fritzsching KJ, Rigney M, Zhou J, Jiang YJ, Schmidt-Rohr K, Xu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:10758. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhou J, Du XW, Li J, Yamagata N, Xu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:10040. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Zhou J, Du XW, Yamagata N, Xu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:3813. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhou J, Du XW, Xu B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:5770. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuang Y, Long MJC, Zhou J, Shi J, Gao Y, Xu C, Hedstrom L, Xu B. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:29208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.600288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Zorn JA, Wille H, Wolan DW, Wells JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19630. doi: 10.1021/ja208350u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Julien O, Kampmann M, Bassik MC, Zorn JA, Venditto VJ, Shimbo K, Agard NJ, Shimada K, Rheingold AL, Stockwell BR, Weissman JS, Wells JA. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:969. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka A, Fukuoka Y, Morimoto Y, Honjo T, Koda D, Goto M, Maruyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;137:770. doi: 10.1021/ja510156v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang C, Bian M, Yang Z. Biomaterials Science. 2014;2:651. doi: 10.1039/c3bm60252d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang P, Gao Y, Lin J, Hu H, Liao H-S, Yan X, Tang Y, Jin A, Song J, Niu G, Zhang G, Horkay F, Chen X. ACS Nano. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Kuang Y, Shi J, Zhou J, Medina JE, Zhou R, Yuan D, Yang C, Wang H, Yang Z, Liu J, Dinulescu DM, Xu B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:13307. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuang Y, Xu B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:6944. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Danks MK, Yoon KJ, Bush RA, Remack JS, Wierdl M, Tsurkan L, Kim SU, Garcia E, Metz MZ, Najbauer J, Potter PM, Aboody KS. Cancer Res. 2007;67:22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Humerickhouse R, Lohrbach K, Li L, Bosron WF, Dolan ME. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kalra AV, Kim J, Klinz SG, Paz N, Cain J, Drummond DC, Nielsen UB, Fitzgerald JB. Cancer Res. 2014;74:7003. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rautio J, Kumpulainen H, Heimbach T, Oliyai R, Oh D, Jarvinen T, Savolainen J. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:255. doi: 10.1038/nrd2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Chan M, Gravel M, Bramoulle A, Bridon G, Avizonis D, Shore GC, Roulston A. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5948. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Guise CP, Abbattista MR, Singleton RS, Holford SD, Connolly J, Dachs GU, Fox SB, Pollock R, Harvey J, Guilford P, Donate F, Wilson WR, Patterson AV. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1573. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huxtable RJ. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:101. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Kuang Y, Gao Y, Xu B. Langmuir. 2011;27:529. doi: 10.1021/la1020324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Web page of HS-5 cells on ATCC homepage. 2015 http://www.atcc.org/Products/All/CRL-11882.aspx#.

- 25.Vanden Berghe T, Kaiser WJ, Bertrand MJM, Vandenabeele P. Molecular & Cellular Oncology. 2015;2:e975093. doi: 10.4161/23723556.2014.975093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.a) Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler M, Larochette N, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Siderovski DP, Penninger JM, Kroemer G. Nature. 1999;397:441. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Slee EA, Zhu HJ, Chow SC, MacFarlane M, Nicholson DW, Cohen GM. Biochem J. 1996;315:21. doi: 10.1042/bj3150021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broker LE, Kruyt FAE, Giaccone G. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3155. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.a) Kammuller ME, Seinen W. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1988;10:997. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(88)90047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Degterev A, Huang ZH, Boyce M, Li YQ, Jagtap P, Mizushima N, Cuny GD, Mitchison TJ, Moskowitz MA, Yuan JY. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:112. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.a) Weston GS, Blazquez J, Baquero F, Shoichet BK. J Med Chem. 1998;41:4577. doi: 10.1021/jm980343w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. J Med Chem. 2016;59:4103. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b02008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.a) Lovell JF, Jin CS, Huynh E, Jin H, Kim C, Rubinstein JL, Chan WCW, Cao W, Wang LV, Zheng G. Nature Materials. 2011;10:324. doi: 10.1038/nmat2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shuhendler AJ, Pu K, Cui L, Uetrecht JP, Rao J. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:373. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zheng Z, Chen PY, Xie ML, Wu CF, Luo YF, Wang WT, Jiang J, Liang GL. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:11128. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lovell JF, Jin CS, Huynh E, MacDonald TD, Cao WG, Zheng G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2429. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.a) Wang Y, Black KCL, Luehmann H, Li W, Zhang Y, Cai X, Wan D, Liu SY, Li M, Kim P, Li ZY, Wang LV, Liu Y, Xia Y. Acs Nano. 2013;7:2068. doi: 10.1021/nn304332s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Xia XH, Yang MX, Oetjen LK, Zhang Y, Li QG, Chen JY, Xia YN. Nanoscale. 2011;3:950. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00874e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carmichael J, Degraff WG, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, Mitchell JB. Cancer Res. 1987;47:936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.