Abstract

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) has been documented in hypertensive adolescents and among some with prehypertension. Obesity also appears to be associated with cardiac mass, independent of blood pressure (BP). Fibroblast growth factor-23(FGF23) is a novel biomarker positively associated with LVH in adults with and without kidney disease. The aim of this study was to determine if there was a significant and independent association of FGF23 with cardiac mass in a Black American adolescent cohort including both normotensive and prehypertensive (PH) participants with and without obesity. Measurements of BP, body mass index (BMI), plasma c-terminal FGF23, and echocardiographic measures of left ventricular mass index (LVMI) were obtained in 236 adolescents, aged 13–18 years, stratified by BMI as normal, overweight, or obese. LVMI differed significantly between normal, overweight, and obese groups (30.42±6.75 vs 33.49 ±8.65 vs 37.26±6.99 gm/m2.7; P<0.01). FGF23 was significantly higher in both overweight (53.03 RU/ml) and obese (54.40 RU/ml) compared to the normal weight (32.83 RU/ml) group; both P<0.01). In multiple linear regression analysis, variables significantly related to LVMI in males were BMI (P<0.0001), and FGF23 (P=0.005), but not BP, hsCRP or insulin. The only significant variable associated with LVMI in females was BMI (P<0.0001). In males, the contribution of FGF23 to predicting LVMI was independent of and in addition to obesity. These results suggest that FGF23 is an integral part of a complex pathway, associated with higher cardiac mass in African Americans males with excess adiposity.

Keywords: Obesity, Cardiac Mass, FGF23, Adolescents, African Americans, Blood Pressure

Introduction

Several reports document an increase in the prevalence of hypertension in childhood during the past decades. This increase is largely, but not entirely, attributable to the concurrent increase in childhood obesity.1,2 Guidelines for evaluation and management of hypertension in children and adolescents published in 2004 recommended evaluating hypertensive children and adolescents for target organ damage, as a measure to facilitate management decisions. Specifically recommended was an echocardiogram to detect left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH).3 Subsequent clinical studies reported that LVH could be detected in 30 to 40 percent of asymptomatic hypertensive children and adolescents with primary hypertension.4,5 It had been assumed that the presence of increased left ventricular mass index (LVMI) or LVH in hypertensive patients was a consequence of the blood pressure (BP) elevation. However, it has been reported that, among hypertensive adolescents, LVH was not related to the severity of hypertension.6 LVH has also been reported among prehypertensive and even normotensive youth.7,8 More recently, evolving evidence indicates there is a significant association of childhood obesity with abnormal cardiac geometry, including LVH. These reports describe a positive relationship of obesity with cardiac mass that appears to be independent of BP.8,9

We previously identified higher LVMI and greater LVH in a selected sample of obese normotensive African American adolescents compared to normal weight normotensive African American adolescents. LVH in obese normotensives could not be explained by traditional obesity-associated metabolic risk factors, inflammatory cytokines or masked hypertension on ambulatory BP monitoring.8 Plasma leptin levels are consistently elevated in obese individuals10, 11 and a recent experimental study reported that leptin increases fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23).12 Therefore, we measured plasma FGF23 in obese and normal weight adolescents. FGF23 was significantly higher in obese normotensives compared to normal weight normotensive adolescents. Moreover, FGF23 was significantly higher among adolescents with LVH compared to those without LVH.13 While these observations in obese and normal weight adolescents were novel, further investigation was needed to confirm the relationship of FGF23 with cardiac mass and structure.

Thus, the purpose of the current study was to test further our hypothesis that there is a positive association of FGF23 with cardiac mass and structure, and that this relationship is independent of high BP. Therefore, we sought to determine if FGF23 levels are higher among overweight as well as obese adolescents, and if there was a significant, independent association of FGF23 with cardiac mass and structure in youth that is in addition to the associations of obesity or elevated blood pressure.

Methods

The study cohort included healthy African American adolescents, age 13 to 18 years, recruited and enrolled in Philadelphia, PA and Wilmington DE, between 2009 and 2012, through primary care practices in the Departments of Family Medicine and Pediatrics at Thomas Jefferson University and from community primary care practices. Non-obese and obese (body mass index ≥ 95th percentile) adolescents were enrolled, as were adolescents with normal BP (average BP <120/80 mm Hg) and adolescents with prehypertension defined as average systolic BP ≥120 mm Hg or average diastolic BP ≥80 mm Hg. Exclusion criteria included known secondary hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disease, thyroid disease, sickle cell disease, eating disorders, and use of steroids. Adolescents with stage 2 hypertension and adolescents with suspected secondary hypertension, based on medical history and urinalysis were also excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Thomas Jefferson University and the A. I. DuPont Hospital for Children. Written informed consent was obtained from 18-year-old participants, while for adolescents age <18 years, consent was obtained from the parent or guardian at enrollment and assent was obtained from the child.

Study Procedures

Data on health status, medication use, and health related behaviors were obtained by self-report of each participant or guardian (for younger adolescents). Clinical assessment consisted of BP and anthropometric measurements (height, weight, and waist circumference). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2), and obesity was defined as BMI ≥95th percentile and overweight was defined as BMI ≥85th and <95th percentile, according to the CDC criteria for children (http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html), which are derived from population-standardized BMI Z-scores based on age, sex, and BMI. In this study on adolescents, prehypertension (PH) was defined as average systolic BP ≥120 mm Hg, or average diastolic BP ≥80 mm Hg but less than the 95th percentile. All BP measurements in this study were obtained by research staff trained in child BP measurement methodology. On each adolescent participant, BP measurements were obtained, by auscultation with an aneroid device, following a 10-minute rest period. During both rest period and BP measurement the adolescent remained in a seated position with his/her back supported and feet flat on the floor. Measurements were performed on the right arm, supported at heart level, using a cuff having a width that was at least 40% of the measured arm circumference and was large enough to encircle 80% of the subject’s upper arm.3 The average of three successive measurements of systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) on two separate visits was used as the BP value for each participant. For adolescents with PH, a third separate set of BP measurements were obtained to ensure that the average of all BP measurements were ≥120 mm Hg systolic or ≥80 mm Hg diastolic BP. BP variables were also calculated based on population-standardized BP Z-scores.3

M-mode 2-dimensional echocardiography was performed, by a single trained research echocardiography technician. Measurements of the left atrial diameter, left ventricular (LV) internal dimension, interventricular septal thickness, and posterior wall thickness during diastole were obtained according to methods established by the American Society of Echocardiography.14 Left ventricular mass (LVM) was calculated from measurement of the LV using the equation LVM (g) = 0.81 [1.04 (interventricular septal thickness + posterior wall thickness + LV end diastolic internal dimension)3 − (LV end diastolic internal dimension)3 +0.06.15 LVM was corrected for height by dividing LVM by height in meters2.7 to calculate LVM index (LVMI).16 LV hypertrophy (LVH) in adolescents, is defined as LVMI ≥95th percentile on sex specific normative LVMI data.17 Left ventricular relative wall thickness (LVRWT) was calculated as 2 × LV posterior wall thickness in diastole/LV internal dimension in diastole. A value > 0.41 was defined as concentric remodeling.

A fasting blood sample was obtained and assayed for metabolic parameters including glucose, insulin, creatinine, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein as previously reported.8 C-terminal FGF23 was assayed on frozen stored plasma samples as previously reported (Immunotopics International, San Clemente, California).13

Statistical Analysis

Participants were stratified into BMI subgroups: Normal weight = BMI ≤ 85th %; Overweight = BMI ≥ 85th % and < 95th %; Obese = BMI ≥ 95th %. Categorical study variables were summarized in these subgroups by frequency counts and percentages. Continuous study variables were summarized by mean and standard deviation except for FGF23, creatinine, insulin and hsCRP which were positively skewed and summarized with geometric means and the first and third quartiles of their respective distributions. These skewed variables were approximately normally distributed after natural log transformation (e.g., logFGF23). Chi square tests and F-tests with 2 degrees of freedom were used to evaluate the unadjusted associations between BMI subgroup and study variables. Comparisons between normal weight and higher BMI groups were adjusted for multiplicity by Dunnett’s test. BMI Z-scores and LVMI were plotted by logFGF23 with ordinary least squares fit lines and Pearson’s bivariate product-moment correlation coefficients to summarize their linear relationships. Ordinary least squares regression was used for multivariable analysis of linear associations between LVMI and logFGF23 while adjusting for age, glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), fasting insulin, SBP, DBP, BMI, and hsCRP. Summary analysis of potential effect modifiers showed that this relationship depended strongly on sex. To address this, we fit separate models to males and females. To evaluate if FGF23 may be involved in the BMI-LVMI causal pathway, we also fit the similar models without the log FGF23 term and compared the respective BMI association results. The significance level for all tests was set in advance at α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary North Carolina).

Results

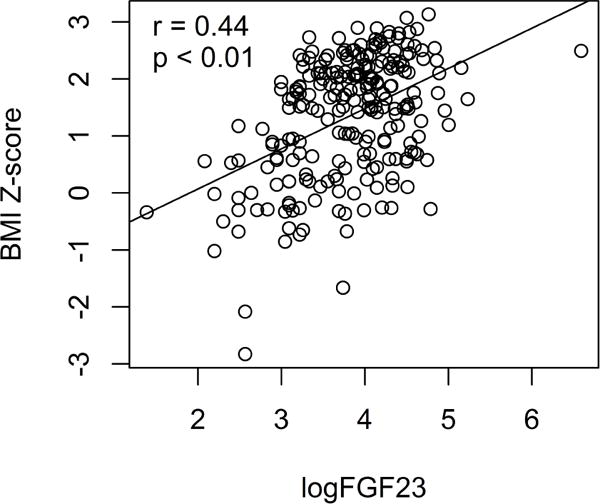

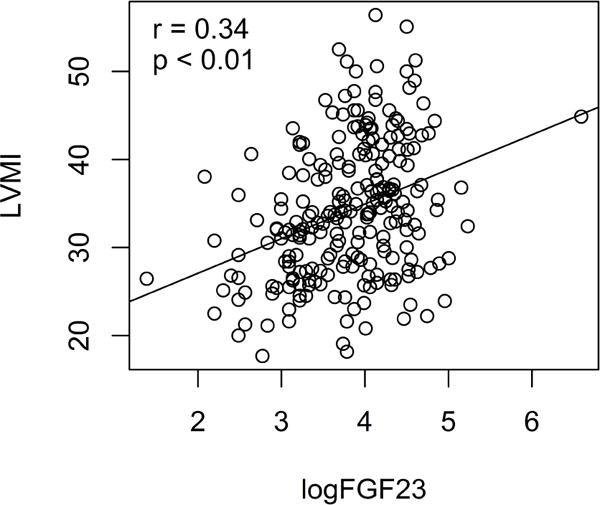

Complete data were available for analysis on 236 adolescent participants. Table 1 provides the mean values in the three BMI groups for age, anthropometric, cardiac mass measures, and FGF23 levels. Mean age was 16 years with no difference among the BMI groups. There were slightly more males (N = 121) than females (N = 115). The portion of this cohort with PH, defined as average BP ≥ 120/80 mm Hg., was 24%. All participants had a serum creatinine level in a normal range, indicating normal renal function. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was also normal in all participants. There were significant differences between BMI groups in cardiac mass measurements. As shown in Table 1, LV mass and LVMI measures were higher in the overweight group compared to the normal weight group, and were significantly higher in the obese group (P<0.01 for both). There were no significant differences among the BMI groups in LVRWT. Compared to the normal weight group, FGF23 was significantly higher in both the overweight group and the obese group with similar FGF23 levels in overweight and obese groups. In contrast, however, mean values for fasting insulin and hsCRP (Table 1) were significantly higher in the obese group compared to both normal and overweight groups, which did not differ significantly from each other. We examined the bivariate correlations of FGF23 with BMI and with LVMI within the entire sample of participants. As shown in Figure 1, there was a significant correlation of logFGF23 with BMI Z-score (r = 0.44, p < 0.01). Additionally, as shown in Figure 2, there was a statistically significant correlation for FGF23 with LVMI (r = 0.34, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Summary statistics by BMI percentile groups.

| Variable | Normal (BMI<85th %) n=86 |

Overweight (85th %≤BMI<95th %) n=33 |

Obese (BMI≥95th %) n=117 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 53 (61.6%) | 15 (45.5%) | 53 (45.3%) | 0.054 |

| Female | 33 (38.4%) | 18 (54.5%) | 64 (54.7%) | |

| BP, n (%) | ||||

| Normal BP | 71 (82.6%) | 24 (72.7%) | 85 (72.7%) | 0.23 |

| High BP* | 15 (17.4%) | 9 (27.3%) | 32 (27.3%) | |

| Age (yrs) | 16.33 (1.74) | 16.06 (1.61) | 16.00 (1.67) | 0.39 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.28 (2.08) | 26.47 (1.59) | 35.48 (6.33) | <.01 |

| BMI Z-score | 0.15 (0.68) | 1.39 (0.17) | 2.21 (0.36) | <.01 |

| Waist Circ. (cm) | 70.56 (7.08) | 82.50 (6.86) | 101.25 (14.31) | <.01 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 109.15 (9.98) | 113.33 (8.81) | 114.79 (11.27) | <.01 |

| SBP Z-score | −0.45 (0.86) | −0.06 (0.78) | 0.10 (0.96) | <.01 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 61.96 (7.93) | 64.02 (7.16) | 62.38 (7.34) | 0.39 |

| DBP Z-score | −0.37 (0.67) | −0.22 (0.62) | −0.36 (0.66) | 0.48 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.78 [0.70, 0.90] | 0.82 [0.70, 1.00] | 0.79 [0.70, 0.90] | 0.56 |

| hsCRP (mg/dl)‡ | 0.40 [0.20, 0.70] | 0.43 [0.20, 0.90] | 1.52 [0.60, 3.50] | <.01 |

| Fasting Insulin | 6.28 (6.69) | 6.99 (3.75) | 13.85 (11.60) | <.01 |

| eGFR | 122.80 (36.29) | 115.11 (24.34) | 120.06 (29.89) | 0.41 |

| LVRWT | 0.36 (0.07) | 0.34 (0.05) | 0.36 (0.08) | 0.19 |

| LVMass (gm) | 123.36 (31.52) | 137.51 (44.15) | 153.06 (38.88) | <.01 |

| LVMI (g/m2.7) | 30.42 (6.75) | 33.49 (8.65) | 37.16 (6.99) | <.01 |

| FGF23 (Ru/mL) | 32.83 [20.0, 60.0] | 53.03 [40.0, 81.0] | 54.40 [38.0, 74.0] | <.01 |

Abbreviations: blood pressure (BP), systolic blood pressure (SBP), body mass index (BMI), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), left ventricular right wall thickness (LVRWT), left ventricular mass (LVMass), left ventricular mass index (LVMI), fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23)

High BP = systolic BP > 120 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP >≥ 80 mm Hg;

Log transformed due to skewed distribution. Geometric means [1st, 3rd quartiles] presented. Normal BP <120/80 mm Hg.

Figure 1.

BMI Z-Score (y axis) is plotted versus logFGF23(x axis) for each participant. There is a significant positive correlation of BMI Z-Score with logFGF23, r = 0.44, p<0.01.

Figure 2.

Left ventricular mass index (LVMI) in Gm/m2.7 (y axis) is plotted versus logFGF23 (x axis) for each participant. There is a significant positive correlation of LVMI with logFGF23, r = 0.34, p<0.01.

Overall, echocardiographic measures on 69 (29%) adolescents met criteria for LVH. We then stratified participants according to cardiac geometry category (normal, concentric remodeling, eccentric LVH, and concentric LVH). As seen in Table 2, compared to those with no LVH (normal cardiac geometry and concentric remodeling), significantly higher FGF23 levels (p< 0.01) were found among those with LVH (eccentric LVH and concentric LVH). Multiple regression analysis was performed separately in males and females to detect the variables that contributed significantly to LVMI. The models are presented in Table 3. As shown in the table, in addition to age, variables that significantly associated with LVMI in males were BMI (P<0.01) and log FGF23 (P=0.01). Fitting the same model with no term for log FGF23 showed that adding log FGF to the model attenuates the association of LVMI with BMI by approximately 10% (from β = 0.53 to β = 0.48) suggesting that FGF23 may play a role in BMI’s influence on LVMI in males. In females, in addition to age, only BMI (P<0.01) was significantly associated with LVMI. In this model, neither fasting insulin nor hsCRP, as a marker of inflammation, were significantly associated with LVMI in males or in females. Fitting the same model with no term for log FGF23 showed that adding log FGF to the model does not attenuate the association of LVMI with BMI in females. Thus, although the dominant predictor of LVMI was BMI, there was an additional, independent relationship between FGF23 and LVMI in African American adolescent males where each 20% increase in FGF23 was associated with a mean increase of 0.51g/m2.7 in LVMI. To illustrate the significance of this association, an increase in FGF23 from the first to third quartile of the male FGF23 sample distribution (i.e., from the middle of the lower half, 29, to the middle of the upper half, 75) was associated with an increase of 2.68g/m2.7 in LVMI. The regression analyses were repeated using BMI Z-score, systolic BP Z-score and diastolic BP Z-score and similar results were obtained. We also repeated the regression analysis but indexed LVM by body surface area (BSA) as the dependent variable. With LVM/m2BSA the only significant independent variable in the model was logFGF23 (P = 0.01), also in males only. Thus, while the dominant predictor of LVMI in African American adolescents was BMI, there was an additional independent relationship of FGF23 with LVMI in males.

Table 2.

FGF23 by LVMI and LVRWT subgroupings.

| No LVH | LVH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n=140) | Concentric Remodeling (n=27) | Eccentric LVH (n=48) | Concentric LVH (n=21) | p-value* | |

| FGF23 | 41.34 | 37.63 | 56.80 | 59.95 | <0.01 |

| (RU/ml)‡ | [25.0, 71.5] | [22.0, 68.0] | [40.0, 81.0] | [45.0, 74.0] | |

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) = LVMI ≥ 95% (Khoury); Concentric Remodeling = LVRWT ≥ 41.0

FGF23 was compared in adolescents without LVH (Normal or Concentric Remodeling) to those with LVH (Eccentric LVH or Concentric LVH). For those without LVH, the geometric mean FGF23 = 40.71, while for those with LVH, the geometric mean FGF23 = 57.74, p < 0.01;

geometric means with [first quartile, third quartile] presented.

Table 3.

Sex-stratified LVMI regression model coefficients (β) for logFGF23, adjusted for age, SBP, DBP, BMI, hsCRP, fasting insulin, and eGFR.

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p | β | 95% CI | p | |

| Intercept | 10.13 | (−7.66, 27.92) | 0.26 | −0.64 | (−23.22, 21.94) | 0.96 |

| Age (years) | 0.39 | (−0.32, 1.11) | 0.28 | 0.25 | (−0.48, 0.99) | 0.49 |

| SBP | −0.04 | (−0.17, 0.09) | 0.55 | 0.07 | (−0.08, 0.21) | 0.35 |

| DBP | 0.05 | (−0.09, 0.20) | 0.46 | 0.05 | (−0.14, 0.24) | 0.61 |

| BMI | 0.48 | (0.26, 0.70) | <.01 | 0.55 | (0.36, 0.74) | <.01 |

| Log hsCRP | −0.50 | (−1.76, 0.76) | 0.43 | −0.72 | (−1.81, 0.38) | 0.20 |

| Insulin | −0.07 | (−0.19, 0.05) | 0.23 | 0.03 | (−0.11, 0.17) | 0.65 |

| eGFR | −0.03 | (−0.06, 0.01) | 0.18 | 0.01 | (−0.03, 0.05) | 0.64 |

| Log FGF23 | 2.82* | (0.87, 4.77) | 0.01 | −0.03 | (−2.19, 2.13) | 0.98 |

dropping FGF23 from these models inflates the BMI coefficient to 0.53 for males, but does not change the BMI coefficient for females.

every 20% increase in FGF23 is associated with an increase of 2.82×loge(1.2) = 0.51g/m2.7 in LVMI.

Discussion

In this large cohort of African American adolescents, with a range of BMI from normal weight to obese and including those with normal BP and PH, we detected a significant association of FGF23 with LVMI in males that was independent and in addition to a significant association of BMI. Among females only BMI was significantly associated with LVMI. In addition, FGF23 was significantly higher in adolescents who had LVH. These results suggest that FGF23 is an integral part of the complex pathway, associated with higher cardiac mass and altered cardiac geometry, in African American males with excess adiposity.

Measures of target organ damage, especially cardiac hypertrophy, are associated with a significant increased risk for cardiovascular events among adult patients with hypertension. Available data from longitudinal studies beginning in childhood, although limited, indicate that childhood obesity and higher BP are both associated with subsequent higher left ventricular mass in young adults.18 Detection of LVH in children and adolescents with less severe BP elevation was first described by Daniels et al.19 who reported a 38.5% prevalence of LVH in a sample of children with average BP above the 90th percentile. The investigators reported that the children with LVH were also obese. An association of obesity with cardiac mass has also been reported in very young children. The Generation R Study, a prospective study in a population of Dutch children during the first two years of life included measures of growth and cardiac structure. These investigators report that at 24 months of age, obese children had significantly greater left ventricular mass compared to normal weight children.20 In these very young children, no significant association of BP with cardiac mass was detected. Whether the associations of obesity with cardiac mass in early childhood represent physiologic adaptations to larger body size or if these findings represent a very early phase of cardiac injury will require further longitudinal investigation. However, alterations in cardiac geometry do raise concern as others have reported abnormal cardiac geometry in obese normotensive children and adolescents.21 22 Recent reports from studies on adolescents and young adults with prehypertension describe significant positive associations of both prehypertension and obesity with LVMI, and these associations with LVMI are independent and additive.7,8 Obesity is associated with a host of abnormal metabolic and physiological consequences that could affect cardiac mass, including metabolic syndrome, sleep apnea, and obesity associated inflammation.23 Our findings of an independent positive association of FGF23 with LVMI suggest a novel biomarker and possible mechanism for abnormal increases in cardiac mass and structure related to adiposity.

FGF23 was initially described for its coordinated endocrine actions in the renal regulation of phosphate homeostasis.24 However, based on experimental animal studies, it was soon recognized that FGF23 had off-target cardiovascular effects that were associated with LVH and cardiac fibrosis.25 Human studies focused initially on adult patients with chronic kidney disease, in which elevations of FGF23 are uniformly present, and found strong associations between plasma FGF23 levels and both altered cardiac structure including LVH and adverse cardiac outcomes.26 Larger scale studies of adult populations generally,27–31 but not uniformly,32 found that incident heart disease also associated with FGF23 plasma levels. It appeared that the strongest relationships between plasma FGF23 levels and adverse cardiac outcomes in adults without overt chronic kidney disease were related to LVH and adverse cardiac structure.27,28,33,34 Added to these observations in adults was our initial study of obese normotensive adolescents, with normal kidney function, that detected higher plasma FGF23 levels compared to non-obese adolescents, and higher FGF23 among those with LVH.13 Taken together, all of these findings suggest that FGF23 could be a biomarker for a mechanistic pathway to explain the observed associations of childhood obesity with increases in cardiac mass.

An inflammatory pathway for cardiovascular injury, as measured by hsCRP, has been described in both adults and children.35–37 Data from our study (Table 1) demonstrate higher plasma insulin and hsCRP among the obese adolescents compared to both overweight and normal weight adolescent participants. In contrast, FGF23 was significantly higher among adolescents in overweight and obesity groups compared to normal weight groups. Moreover, multiple regression analysis detected a significant positive association of logFGF23 on LVMI that was independent and in addition to obesity, overweight, or prehypertension. In this analysis no significant association of insulin or of hsCRP with LVMI was detected that was independent of obesity. These results suggest that relationships of FGF23 with adiposity and LVMI differ from the relationships of insulin and of inflammation with adiposity.

There were some limitations in our study. Study participants included only African Americans, thus limiting generalizability to other race/ethnic groups. However, cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality are greater among African Americans compared to other racial and ethnic groups. In the prospective Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, high BP with high BMI in young adult African Americans men were found to be associated with subsequent premature heart failure.38 An earlier study by Dekkers et al.39 investigated LVM growth in African American and White youth in a prospective study from childhood to early adulthood. These investigators found greater LVM in African Americans and in males compared to Whites and females, with the ethnicity and gender effects emerging in adolescence. In their study, BMI and height were the strongest anthropometric predictors of LVM, with the prospective data demonstrating that cardiac growth was largely explained by body growth and increasing adiposity. Thus we chose to investigate factors associated with target organ damage in African Americans. Our findings add some additional insights on this cardiovascular disease disparity.

We do not have data on plasma or urine phosphate, or other mineral parameters that could be related to FGF23 levels. It is also possible that the highest levels of FGF23 in our obese adolescents are related to a high dietary phosphate intake, as phosphate intake has been described as a primary driver for FGF23 levels in populations without chronic kidney disease. Because our investigations on FGF23 were conducted following the original cohort study we did not obtain samples or dietary information on Phosphate. However, our findings of a strong association of FGF23 with obesity in adolescents are consistent with a recent report on a large cross-sectional study in adults over age 45 years who were participants in the Reason for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.40 The investigators reported that the leading variables associated with high FGF23, in both male and female participants without kidney disease, were BMI, waist circumference, inflammatory markers (hsCRP, IL-6, IL-10). Measures of cardiac structure were not included their study. Although the authors describe examining calcium and phosphorus intake by quartile of plasma FGF23 level, no significant relationships were reported. Despite the absence of traditional variables of mineral metabolism related to blood levels of FGF23 in our study, the association of FGF23 with LVMI in males is quite strong, and it is likely that the mechanistic pathway in which FGF23 is related to cardiac hypertrophy is different than the pathway in which FGF23 is engaged in vascular calcification.

Our study was cross-sectional thereby limiting our findings to associations. Since it is not possible to confirm causality from data based on a cross-sectional study design, it cannot be determined if FGF23 contributes to development and progression of abnormal cardiac mass and structure. Moreover, from our study it cannot be determined if the absence of a significant association of FGF23 with LVMI in females is due to gender differences body fat distribution with greater visceral adiposity in males compared to females; or if the relationship of FGF23 with LVMI emerges at a later age. Additional prospective investigations are needed to clarify a potential role of FGF23 in the evolution of cardiovascular disease.

We previously found that FGF23 was higher in obese normotensive adolescents compared to non-obese normotensive adolescents. In that same study, we also detected a significant positive association of FGF23 with LVMI and LVH.13 In the current study we expanded the cohort size and also included participants with prehypertension. While analysis of our data detected the expected associations of obesity and overweight, with LVMI and LVH, we did not detect an association of BP level with LVMI. However, BP levels in the prehypertensive range were only modestly elevated. Analysis of our data did detect a significant positive association of FGF23 with LVMI and adverse cardiac mass that was additive to and independent of BMI in males. Thus, since FGF23 also attenuated the association of LVMI with BMI by approximately 10%, we conclude that FGF23 may be engaged in a mechanistic pathways whereby obesity leads to adverse cardiac outcomes.

Conclusion

LVH is commonly found in adolescents with obesity associated hypertension. Results in our study extend these associations to overweight and obesity in African American adolescents. In this cohort, FGF23, a biomarker linked with LVH in adults, was significantly higher among obese African American adolescent males, and there was also a significant independent association of FGF23 with cardiac mass. A significant association of FGF23 with LVMI was not detected in adolescent females. Our findings indicate that FGF23 may be part of the complex pathway in which African American males with excess adiposity develop early onset cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This study was funded in part from a grant from the National Institutes of Health HL092030.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Munter PHJ, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, Welton PK. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291:2107–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosner B, Cook NR, Daniels S, Falkner B. Childhood blood pressure trends and risk factors for high blood pressure: the NHANES experience 1988–2008. Hypertension. 2013;62:247–254. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falkner B, Daniels S, Flynn JT, et al. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanevold C, Waller J, Daniels S, Portman R, Sorof J. The effects of obesity, gender, and ethnic group on left ventricular hypertrophy and geometry in hypertensive children: a collaborative study of the International Pediatric Hypertension Association. Pediatrics. 2004;113:328–333. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNiece KL, Gupta-Malhotra M, Samuels J, Bell C, Garcia K, Poffenbarger T, Sorof JM, Portman RJ. Left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive adolescents: analysis of risk by 2004 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group staging criteria. Hypertension. 2007;50:392–395. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.092197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brady TM, Fivush B, Flynn JT, Parekh R. Ability of blood pressure to predict left ventricular hypertrophy in children with primary hypertension. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008;152:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urbina EM, K P, McCoy C, Daniels SR, Kimball TR, Dolan LM. Cardiac and vascular consequences of pre-hypertension in youth. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn) 2011;13:332–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falkner B, DeLoach S, Keith SW, Gidding SS. High risk blood pressure and obesity increase the risk for left ventricular hypertrophy in African-American adolescents. The Journal of pediatrics. 2013;162:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pieruzzi F, Antolini L, Salerno FR, Giussani M, Brambilla P, Galbiati S, Mastriani S, Rebora P, Stella A, Valsecchi MG, Genovesi S. The role of blood pressure, body weight and fat distribution on left ventricular mass, diastolic function and cardiac geometry in children. Journal of hypertension. 2015;33:1182–1192. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, McKee LJ, Bauer TL, Caro JF. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. The New England journal of medicine. 1996;334:292–295. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanches PL, de Mello MT, Elias N, et al. Hyperleptinemia: implications on the inflammatory state and vascular protection in obese adolescents submitted to an interdisciplinary therapy. Inflammation. 2014 Feb;37(1):35–43. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9709-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuji K, Maeda T, Kawane T, Matsunuma A, Horiuchi N. Leptin stimulates fibroblast growth factor 23 expression in bone and suppresses renal 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 synthesis in leptin-deficient mice. Journal of bone and mineral research. 2010;25:1711–1723. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali FN, Falkner B, Gidding SS, Price HE, Keith SW, Langman CB. Fibroblast growth factor-23 in obese, normotensive adolescents is associated with adverse cardiac structure. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014;165:738–743 e731. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, Reichek N. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. The American journal of cardiology. 1986;57:450–458. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Simone G, Devereux RB, Daniels SR, Koren MJ, Meyer RA, Laragh JH. Effect of growth on variability of left ventricular mass: assessment of allometric signals in adults and children and their capacity to predict cardiovascular risk. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1995;25:1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoury PR, Mitsnefes M, Daniels SR, Kimball TR. Age-specific reference intervals for indexed left ventricular mass in children. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:709–714. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urbina EM, Gidding SS, Bao W, Pickoff AS, Berdusis K, Berenson GS. Effect of body size, ponderosity, and blood pressure on left ventricular growth in children and young adults in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Circulation. 1995;91:2400–2406. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniels SD, Meyer RA, Loggie JM. Determinants of cardiac involvement in children and adolescents with essential hypertension. Circulation. 1990;82:1243–1248. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.4.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Jonge LL, van Osch-Gevers L, Willemsen SP, Steegers EA, Hofman A, Helbing WA, Jaddoe VW. Growth, obesity, and cardiac structures in early childhood: the Generation R Study. Hypertension. 2011;57:934–940. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dusan P, Tamara I, Goran V, Gordana ML, Amira PA. Left ventricular mass and diastolic function in obese children and adolescents. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany) 2015;30:645–652. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2992-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Salvo G, Pacileo G, Del Giudice EM, Natale F, Limongelli G, Verrengia M, Rea A, Fratta F, Castaldi B, D’Andrea A, Calabro P, Miele T, Coppola F, Russo MG, Caso P, Perrone L, Calabro R. Abnormal myocardial deformation properties in obese, non-hypertensive children: an ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, standard echocardiographic, and strain rate imaging study. European heart journal. 2006;27:2689–2695. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brady TM. The role of obesity in the development of left ventricular hypertrophy among children and adolescents. Current hypertension reports. 2016;18:3–11. doi: 10.1007/s11906-015-0608-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin A, David V, Quarles LD. Regulation and function of the FGF23/klotho endocrine pathways. Physiological reviews. 2012;92:131–155. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grabner A, Amaral AP, Schramm K, et al. Activation of Cardiac Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 4 Causes Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Cell metabolism. 2015;22:1020–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scialla JJ, Xie H, Rahman M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and cardiovascular events in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:349–360. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kestenbaum B, Sachs MC, Hoofnagle AN, Siscovick DX, Ix JH, Robinson-Cohen C, Lima JA, Polak JF, Blondon M, Ruzinski J, Rock D, de Boer IH. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and cardiovascular disease in the general population: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation Heart failure. 2014;7:409–417. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathew JS, Sachs MC, Katz R, Patton KK, Heckbert SR, Hoofnagle AN, Alonso A, Chonchol M, DEo R, Ix JH, Siscovick DS, Kestenbaum B, de Boer IH. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and incident atrial fibrillation: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Circulation 22. 2014;130:298–307. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lutsey PL, Alonso A, Selvin E, Pankow JS, Michos ED, Agarwal SK, Loehr LR, Eckfeldt JH, Coresh J. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and incident coronary heart disease, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014;3:e000936. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alonso A, Misialek JR, Eckfeldt JH, Selvin E, Coresh J, Chen LY, Soliman EZ, Agarwal SK, Lutsey PL. Circulating fibroblast growth factor-23 and the incidence of atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014;3:e001082. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright CB, Dong C, Stark M, Silverberg S, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Sacco RI, Mendez A, Wolf M. Plasma FGF23 and the risk of stroke: the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) Neurology. 2014;82:1700–1706. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor EN, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Plasma fibroblast growth factor 23, parathyroid hormone, phosphorus, and risk of coronary heart disease. American heart journal. 2011;161:956–962. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal I, Ide N, Ix JH, Kestenbaum B, Llanske B, Schiller NB, Whooley MA, Mukamal KJ. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and cardiac structure and function. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014;3:e000584. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jovanovich A, Ix JH, Gottdiener J, McFann K, Katz R, Kestanbaum B, de Boer IH, Sarnak M, Shlipak MG, Mukamal KJ, Siscovick D, Chonchol M. Fibroblast growth factor 23, left ventricular mass, and left ventricular hypertrophy in community-dwelling older adults. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Festa A, D’Agostino R, Jr, Howard G, Mykkanen L, Tracy RP, Haffner SM. Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Circulation. 2000;102:42–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinaiko AR, Steinberger J, Moran A, Prineas RJ, Vessby B, Basu S, Tracy R, Jacobs DR., Jr Relation of body mass index and insulin resistance to cardiovascular risk factors, inflammatory factors, and oxidative stress during adolescence. Circulation. 2005;111:1985–1991. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161837.23846.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Litwin M, Michalkiewicz J, Niemirska A, Gackowska L, Kubiszewska I, Wierzbicka A, Wawer ZT, Janas R. Inflammatory activation in children with primary hypertension. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany) 2010;25:1711–1718. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM, Arynchyn A, Lewis CE, Williams OD, Hulley SB. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360:1179–1190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dekkers C, Treiber FA, Kapuku G, van den Oord JCG, Snieder H. Growth of left ventricular mass in African American and European American youth. Hypertension. 2002;39:943. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000015612.73413.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanks LJ, Casazza K, Judd SE, Jenny NS, Gutierrez OM. Association of fibroblast growth factor-23 with markers of inflammation, insulin resistance and obesity in adults. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0122885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]