Abstract

Introduction

Age-related decline in the intrinsic lingual musculature could contribute to swallowing disorders, yet the effects of age on these muscles is unknown. We hypothesized reduced muscle fiber size and shifts to slower MyHC fiber types with age.

Methods

Intrinsic lingual muscles were sampled from 8 young-adult (9 months) and 8 old (32 months) Fischer 344/Brown Norway rats. Fiber size and MyHC were determined by fluorescent immunohistochemistry.

Results

Age was associated with a reduced abundance of rapidly-contracting muscle fibers, and more slowly-contracting fibers. Decreased fiber size was found only in the transverse and verticalis muscles.

Discussion

Shifts in muscle composition from faster to slower MyHC fiber types may contribute to age-related changes in swallowing duration. Decreasing muscle fiber size in the protrusive transverse and verticalis muscles may contribute to reductions in maximum isometric tongue pressure found with age. Differences among regions and muscles may be associated with different functional demands.

Keywords: Age, Swallow, Dysphagia, Tongue, Lingual

Introduction

Swallowing disorders occur in up to 40% of people over the age of 60, and as the elderly population continues to expand, age-related swallowing disorders are expected to be an increasing clinical problem1. Even in healthy individuals, aging is associated with weaker maximum tongue strength2 and longer swallow durations, specifically within the oral stage3. Muscles of the tongue are active throughout the oropharyngeal swallow4 and are functionally divided into the extrinsic muscles, which are anchored to bones, and intrinsic muscles, which are interdigitated within the blade of the tongue. Previous studies on age-related changes of swallowing muscle biochemistry have focused on extrinsic tongue muscles as well as laryngeal muscles5–7, while intrinsic tongue muscles have received less scientific study.

The complexity and interdigitation of the intrinsic tongue muscles makes them challenging to isolate and study. Nevertheless, the intrinsic muscles contribute substantially to swallowing, speech, chewing, and respiration8–11. One indication of the importance of the intrinsic muscles is that up to 80% of the hypoglossal motor neurons innervating the tongue are devoted to the intrinsic muscles12–14.

Cranial muscles, including the tongue, typically have properties that make them unique from other skeletal muscles 15. Tongue muscles have high levels of capillarization and hybrid fibers that express more than one myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoform, yet lack the high levels of developmental MyHC isoforms found in some cranial muscles15,16. Aging has been shown to differentially effect tongue and limb muscle. For instance, the tongue was found to contract more slowly with age, but did not exhibit the loss of force generation seen in the extensor digitorum longus17. Further, it is possible that aging may have differential effects among tongue muscles, as observed within the intrinsic laryngeal muscles. With age, the cricothyroid muscle was found to have decreased fiber numbers, decreased fiber size, and changes in MyHC fiber types, yet no changes were found in the posterior cricoarytenoid7. Understanding how aging impacts muscles of the tongue would contribute to this growing knowledge of cranial muscle biology and may contribute to improvements in the treatment of age-related swallowing disorders.

While many muscles across the upper aerodigestive tract are involved in swallowing, the tongue is one of the primary targets of swallowing therapy18–21. Accordingly, understanding how tongue muscles may be altered by aging has clinical implications that may help to refine treatments. Because noncadaveric human tongue tissue is difficult to obtain for research purposes, a rat model was developed to examine biological aspects of tongue muscle changes as a function of aging. In this rat model, the extrinsic genioglossus muscle exhibited age related shifts in MyHC isoform composition, with decreased percentages of fast contracting MyHC isoform IIb, as well as changes in muscle contraction properties including slower contraction times22–24. However, the effects of age on intrinsic tongue muscles is not known. This knowledge is important because there is evidence that the intrinsic muscles have a substantial role in swallowing8, particularly in the oral stage of bolus formation and propulsion10,25.

Our goal was to determine whether there are age-related changes in muscle fiber size and MyHC fiber types in each of the intrinsic lingual muscles. Our hypothesis was that old age would be associated with reductions in muscle fiber size, decreased percentages of muscle fibers composed of fast contracting MyHC IIb, and increased percentages of the slower MyHC IIa muscle fibers.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Tongue muscle samples were collected from 8 old (32 month) and 8 young adult (9 month) male Fischer 344/Brown Norway rats (National Institute on Aging colony, Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN). This strain of rat is used in aging research and has a median life span of 34 months26,27. Experiments were approved by the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Animal Care and Use Committee.

Muscle Samples

Whole intrinsic tongues were collected and snap frozen in OCT compound (Tissue Tek) using liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane and stored at −80°C. Intrinsic tongue muscle samples were dissected at −20°C as shown in Figure 1, re-embedded in OCT, and snap frozen to avoid thawing. The superior longitudinal, inferior longitudinal, transverse, and verticalis muscles were sampled. As intrinsic tongue muscle properties have been shown to differ from the anterior to the posterior of the tongue28, each muscle was sampled from the anterior, middle, and posterior regions. Cross sections of the longitudinal muscles were obtained coronally, transverse muscles parasagitally, and verticalis muscles horizontally28. Individual muscle samples were cut into 10μm thick sections on a cryostat (Leica).

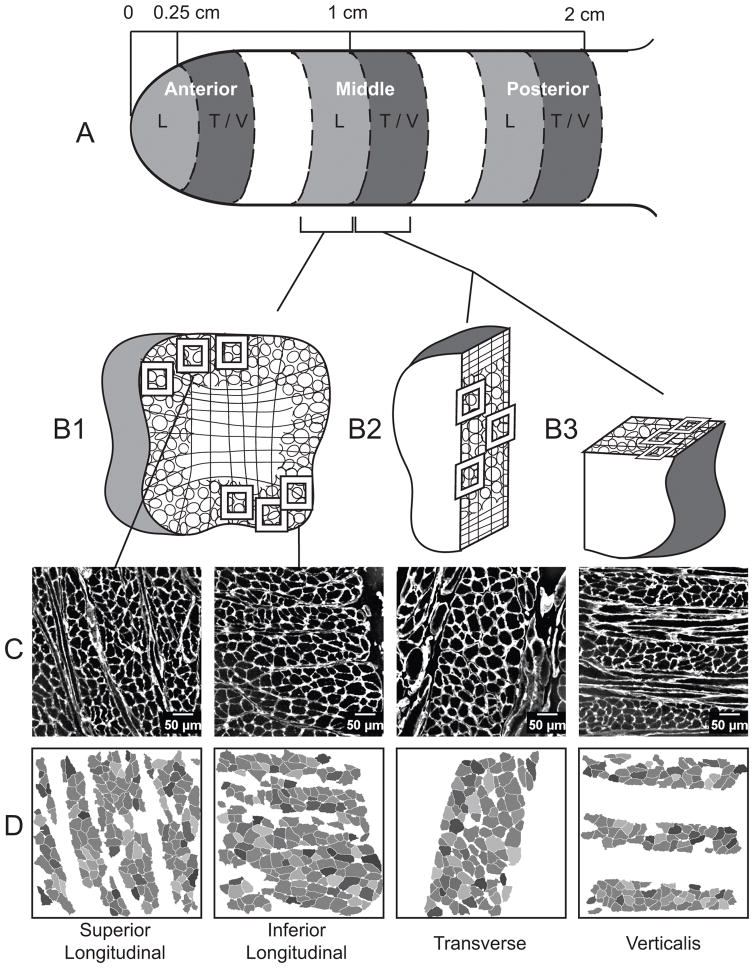

Figure 1.

Methods for obtaining cross sections of intrinsic muscle fibers. A. Two 0.25cm samples were collected from each tongue region: anterior, middle, and posterior. B1. One sample was sectioned coronally with the longitudinal muscles in cross section. The longitudinal sections were taken from the side of the tissue sample that abutted the transverse and verticalis samples such that all muscles in a region were sampled at a consistent distance from the apex of the tongue. The second sample in each region was divided in half. The sagittal cut provided the transverse muscle cross section (B2), and the remaining half was trimmed and sectioned in the transverse plane, with the verticalis muscle fibers in cross section. Boxes indicate typical locations of muscle fiber image collection. Verticalis images were collected near the outer edge of the tongue (B3) to reduce the likelihood of including genioglossus fibers, which are known to run vertically in the center of the tongue. C. Example images of muscle sections with muscle fibers indicated by fluorescent IHC for laminin. D. Muscle fiber cross sections identified and analyzed by SMASH software. Sample collection from the middle region is shown, anterior and posterior samples were collected in the same manner.

Immunofluorescent Staining

Myosin heavy chain is a prime determinant of muscle fiber type29. Accordingly, based on Bloemberg and Quadrilatero30, primary antibodies from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa) were used to identify muscle fibers positive for MyHC type I (BA-F8, 1:50), IIa (SC-71,1:600), IIx (6H1, 1:100), and IIb (BF-F3, 1:200)30–34. Because the primary antibodies for IIx and IIb fibers bind the same secondary antibodies, two sequential slides were prepared for each muscle, one stained for MyHC type I, IIa, and IIb, and the other for MyHC type IIa and IIx (Figure 2). Additionally, all samples were stained with laminin (sigma-aldrich, 1:1000). Slides were fixed in cold (4° C) acetone for 10min, washed, and incubated for 30 min in a blocking serum of PBS with 10% goat serum. Each group of primary antibodies was prepared in the 10% goat blocking serum, and applied to the samples for 1 hour at room temperature. After several washes, secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 350 IgG2b, Alexa Fluor 488 IgG1, Alexa Fluor 555 IgM, and 633 IgG Invitrogen) were applied and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were washed, dried, and coverslipped with Prolong Gold (ThermoFisher). In total, there were two sequential sections of each muscle, from each region. Each muscle section was imaged with three randomly sampled fields of view, for a total of 18 images per muscle (2 sections × 3 regions × 3 images). Images were collected at 20x, using a Nikon N-STORM microscope with an Andor iXon 897 EMCCD camera. To ensure a high fiber density of the desired muscle, longitudinal muscles were imaged near the edges of the tongue (Figure 1, panel B1), while the transverse was imaged centrally (Figure 1, panel B2). The verticalis was sampled near the side of the tongue to minimize the inclusion of genioglossus fibers which run vertically in the center of the tongue (Figure 1, panel B3)35–39. With a constant image size, the number of fibers per image varied due to the size and density of the fibers. The average number of fibers included in the analysis of a muscle section across regions was 315 with a standard deviation of 106.

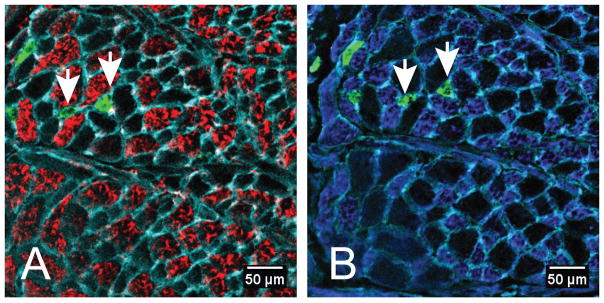

Figure 2.

Representative image of MyHC expression in serial sections of the inferior longitudinal muscle sampled from the middle region of the tongue. Both sections were stained for expression of MyHC IIa (green) and laminin (cyan), which outlines the muscle fibers. The same two MyHC IIa positive fibers are indicated by white arrows in each panel. Panel A demonstrates expression of MyHC IIb (red), and MyHC IIx (blue) expression is shown in panel B. Unstained muscle fibers in panel A correspond with MyHC IIx positive muscle fibers in panel B.

Fiber Typing and CSA

The Matlab application SMASH 40 was used to determine the size and MyHC types of each muscle fiber. Positive staining thresholds for each image were verified by a second researcher. The percent of the measured fibers positive for each MyHC type was determined. We inferred muscle fiber type from MyHC composition for each muscle fiber sampled, because MyHC composition is a primary determinant of the fiber type41. A hybrid fiber, positive for two or more MyHC types, was counted for each MyHC type for which it was positive. Muscle fiber size was measured as minimum Feret’s diameter, which is robust to the angle at which the fiber was cut42. Muscle fiber data generated in SMASH were compiled for analysis in Mathematica (Wolfram).

Statistical Analysis

Muscle fiber type (MyHC) percentages were analyzed using a mixed design repeated measures ANOVA. The between-subjects factor was age (young adult versus old), while the within subject factors were region and muscle. The three dependent measures were the percent of MyHC IIb, IIa, and IIx. Fibers positive for type I MyHC were very rare and were not included in any analyses. Greenhouse-Geisser adjusted p-values and degrees of freedom were reported because Mauchly’s test for sphericity was significant for several cases. However, significance did not differ between adjusted and non-adjusted p-values. The adjusted degrees of freedom are non-integer values and differ between fiber type and variable. Significance was determined using α < 0.05 as the critical value.

Linear mixed effects models were used to assess muscle fiber size for each MyHC type. Age, region, and muscle were modeled as fixed effects, with individual subjects as random effects. All interactions between age, muscle, and region were included in the model. The dependent variable was the mean minimum Feret’s diameter for each muscle fiber type (IIb, IIx, IIa). Animal weight was included as a covariate because mean fiber size was significantly and moderately correlated with weight (Pearson’s r = 0.49, p = 0.05). When significant interactions were found, the Sidak posthoc test was used to assess pairwise differences. Degrees of freedom varied across analyses due to differences in detection of specific MyHC isoforms across samples. Specifically, muscle fibers positive for MyHC type IIa were not present in 44 samples and muscle fibers positive for MyHC IIb were not present in 17 samples. All statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 22.

Results

Muscle Fiber Type Percentages

There were no significant interaction effects between age and muscle, as well as no significant three-way interactions among age, region, and muscle. However, a significant interaction effect between muscle and region was found for all MyHC types indicating differences among muscles vary by region (MyHC IIb: F(3.41,47.68) = 4.042, p = 0.009; MyHC IIx: F(3.65,51.12) = 6.12, p = 0.001; MyHc IIa: F(3.77,52.72) = 4.40, p = 0.004).

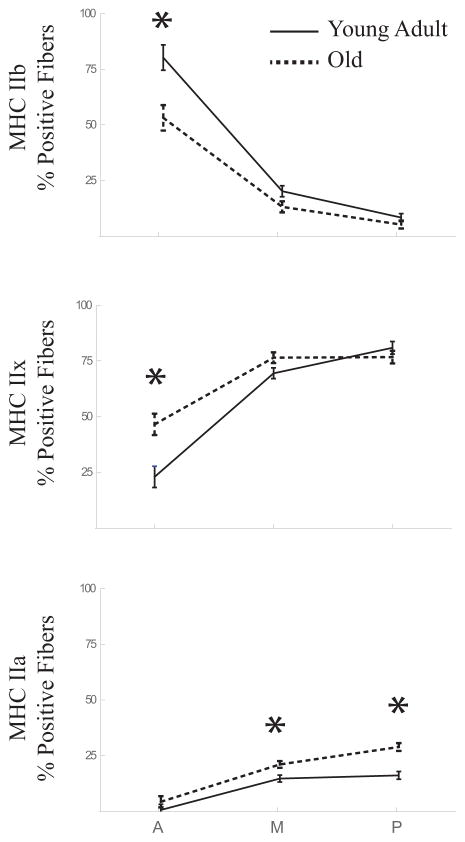

In both young adult and aged animal groups, MyHC IIb positive muscle fibers were most abundant in the anterior of the tongue and decreased progressively toward the posterior tongue (Figure 3, top panel). In contrast, MyHC IIx and IIa fibers were least abundant in the anterior and increased toward the posterior tongue (Figure 3, middle and bottom panels, respectively).

Figure 3.

Age related differences in MyHC fiber type composition of the intrinsic muscles vary by region in the tongue. The percentage of fibers positive for MyHC IIb, IIx and IIa are shown for samples from the anterior (A), middle (M), and posterior (P) regions of the tongue. Significant differences between young adult (solid lines) and old (dashed lines) groups, as determined by post hoc testing, are indicated by asterisks. In the anterior region, old animals had less of the fastest MyHC IIb positive fibers (young adult = 80.19±5.69%, old = 53.19±5.69%, p = 0.005), and more fibers positive for MyHC IIx (young adult = 23.02±4.79%, old = 46.56±4.79%, p = 0.004). The slowest MyHC IIa muscle fibers were more common in the aged animals, with significantly higher percentages in the middle (young adult = 14.75±1.52%, old 21.1±1.52%, p = 0.011) and posterior (young adult = 16.2±1.75%, old = 28.91±1.75%, p < 0.001) regions.

Across all muscles, there was a significant main effect for age on the percentage of muscle fibers positive for MyHC type IIa (F(1.46,20.47) = 60.4, p <0.001). Post hoc analyses revealed that MyHC type IIa muscle fibers were more common in the old group, with significantly higher percentages in the middle and posterior regions of the tongue. A significant interaction was found between age and region for the percentage of muscle fibers positive for MyHC IIb and MyHC IIx (F(1.29,18.62) = 6.10, p = 0.018; F(1.35, 18.93) = 8.29, p = 0.006, respectively; Figure 3). Post hoc pairwise tests determined that in the anterior region, the young adult group had significantly more fibers positive for MyHC type IIb, while the old group had more fibers positive for MyHC IIx.

Muscle Fiber size

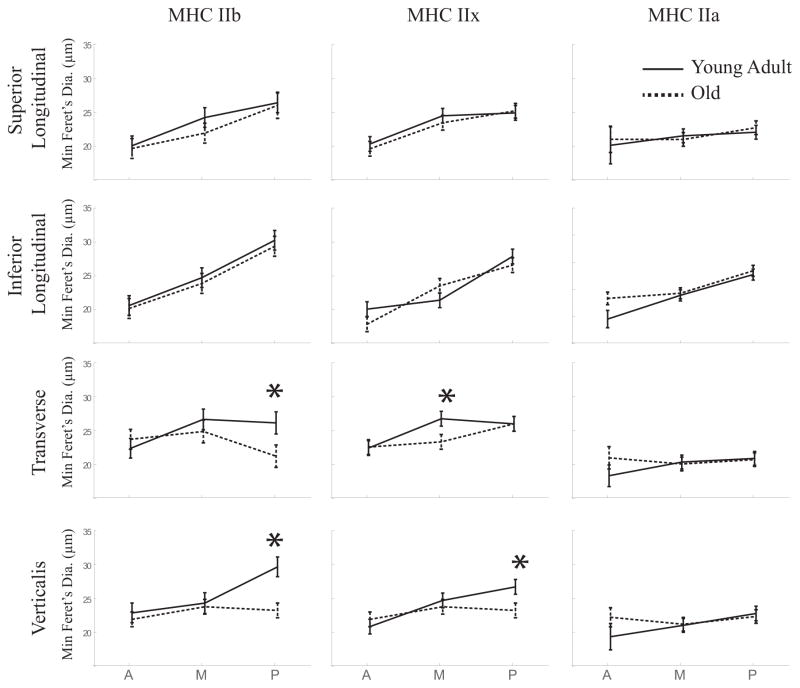

Generally, fibers within all muscles studied were larger in the posterior versus anterior regions of the tongue. (Figure 4). In muscle fibers positive for MyHC type IIb, there was a significant interaction between age and region (F(2, 138.78) = 4.01, p = 0.02). That is, in the posterior region of the transverse and verticalis muscles, the old group had significantly smaller muscle fibers. An age-region-muscle interaction was significant for MyHC IIx positive muscle fibers (F(6,154) = 2.63, p = 0.019). Posthoc testing determined the middle transverse muscle fibers and posterior verticalis fibers were significantly smaller in the old group. No significant fiber size differences between age groups were found in the longitudinal muscles.

Figure 4.

Significant age-related differences in fiber size occurred in the transverse and verticalis muscles for MyHC IIb and MyHC IIx positive muscle fibers. Sidak’s post hoc test was used to determine significant pairwise comparisons. In the aged animals (dashed lines), MyHC IIb positive fibers were smaller in the posterior region for both the transverse (young adult = 26.12±1.63μm, old = 21.22±1.63 μm, p = 0.048) and verticalis muscles (young adult = 29.65±1.45μm, old = 19.94±1.81 μm, p < 0.001). MyHC IIx positive fibers were also significantly smaller for the old animal group in the middle transverse muscle fibers (young adult = 26.73±1.09 μm, old = 23.33±1.09 μm, p = 0.04), and posterior verticalis fibers (young adult = 26.70±1.09 μm, old = 23.23±1.09 μm, p = 0.036).

Discussion

We hypothesized that age would be associated with reductions in muscle fiber size, decreased percentages of muscle fibers composed of rapidly-contracting MyHC IIb, and increased percentages of the slower MyHC IIa muscle fibers. Our findings supported these hypotheses in that age was associated with increased percentages of more slowly contracting muscle fiber types and reductions in fiber size that were region and muscle specific.

Our findings are consistent with the aging literature in studies of both extrinsic lingual and intrinsic laryngeal muscles7,24. As has been seen in human cadaveric intrinsic tongue muscles28, both muscle fiber size and composition varied from the anterior to the posterior of the rat tongue. Specifically, muscle fiber diameter increased with distance from the tip of the tongue, more rapidly-contracting muscle fibers were found in the anterior tongue, and a greater percentage of slower fibers in the posterior tongue. Interestingly, this anterior-to-posterior shift in muscle fiber types is the inverse of the extrinsic genioglossus muscle, in which the highest proportion of MyHC IIb was found in the posterior tongue, and the highest percentages of the MyHC IIa isoform was in the anterior region5. Therefore, our findings reinforce the value of this animal model for studying the changes in biological mechanisms underlying age-related decrements in tongue function, and endorse differences between intrinsic and extrinsic lingual muscles.

Differences among intrinsic muscles and tongue regions may be associated with different functional demands, although the specific functional contributions of the different muscles and regions of the tongue are not yet well understood. Smaller diameter muscle fibers in the anterior region of the tongue may allow for fine motor control28, while larger diameter muscle fibers in the middle and posterior tongue regions may contribute to bolus driving forces for propulsion into the hypopharynx. Faster-contracting intrinsic muscle fibers in the anterior tongue may be necessary for rapid responses to bolus movement or transport, or potential bolus containment perturbations during mastication. Furthermore, slower contracting muscle fibers with increased endurance may be necessary in the posterior regions of the intrinsic tongue muscles to maintain airway patency43,44.

Overall, the old group showed a decrease in the rapidly-contracting MyHC IIb muscle fibers, and in increase in IIx and IIa fibers. That is, more slowly contracting and fatigue-resistant muscle fibers were more common in the old group. One feature of swallowing in aged populations is a longer swallow duration. The shifts in muscle composition from faster to slower MyHC muscle fiber types may contribute to age related changes in swallowing speed, but in turn may provide the endurance necessary for eating an entire meal45,46.

Age-related reductions in IIb and IIx muscle fiber size occurred only in specific intrinsic tongue muscles as a function of region. That is, significant reductions in muscle fiber size with age were only found in the middle and posterior transverse and verticalis muscles. No significant age differences in fiber diameter were found in the longitudinal muscles. Two previous studies of human cadaveric tongues reported conflicting results as to whether longitudinal muscle fiber atrophy was manifested with increasing age47,48. That is, a trend of decreasing superior longitudinal muscle fiber diameter with age is in opposition to a report of increasing muscle fiber cross-sectional area near the lingual root after age 4447,48. Different age ranges, muscle sample locations, and muscle fiber selection parameters may have contributed to the different findings. Mixed results have also been reported on the impact of aging on the extrinsic lingual muscles 5,24,49–51. Because imaging and EMG studies have indicated that the transverse and verticalis muscles may work with the genioglossus to propel the bolus during swallowing 8,52, decreasing muscle fiber size in the transverse and verticalis muscles, as reported in our study, may contribute to the reductions in maximum tongue pressure found with age2.

A possible interpretation of differential findings across intrinsic tongue muscles may be that muscles with important respiratory functions are spared from aging effects. This interpretation was offered in a study of aging in the intrinsic laryngeal muscles. Specifically, the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle, which is involved in respiration, did not show any significant age related changes, in contrast to the other muscles studied7. In this study, the superior longitudinal muscle, which is also active during inhalation44, appeared to have the least age related decline. It has also been suggested that the far posterior transverse muscle fibers may have a role in maintaining the airway 43. The posterior transverse muscle samples used in this study may not have captured fibers with a respiratory function, yet we only found age-related size reductions in the IIb fibers, which are not typically relied on for normal quiet breathing53.

There are some limitations in the current work. First, cranial muscles have a high percentage of hybrid muscle fibers that are positive for more than one MyHC type15. We chose to include hybrid fibers in each MyHC type for which they were positive. Exclusion of these hybrid fibers or reclassification into a separate category may have reduced variability in the results. Second, we chose to measure a randomly sampled subset of muscle fibers from each muscle cross-section and did not include all fibers within a muscle. Analysis of complete muscle cross-sections may have improved accuracy and provided additional data such as the total number of fibers in a muscle. Third, because the extrinsic muscles interdigitate with the intrinsics, it is likely that some samples included extrinsic muscle fibers, particularly in the posterior region. Although great care was taken to only include intrinsic muscle fibers, the possibility exists that genioglossus fibers were included in the posterior verticalis, while the inferior longitudinal samples may have included styloglossus and hyoglossus fibers. This particular limitation was unavoidable due to the complexity of tongue anatomy.

Tongue exercises are used to treat dysphagia and have been shown to increase tongue strength and improve patients’ swallowing function and quality of life19. Experiments to understand how these exercises affect aged muscles and improve treatments have focused on the genioglossus49,24. The results of this study suggest that age related declines in the intrinsic muscles, particularly the transverse and verticalis, may also be a consideration in the aged swallow. Accordingly, the manner in which treatments in current clinical use, such as tongue exercise, alter the characteristics of the intrinsic muscles of the tongue should be addressed in future studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Brittany Krekeler and Austin Potrue in the completion of this work. This work was funded from the following sources: NIH grants T32DC009401, R01DC008149, R01DC005935, and R01DC014358.

Abbreviations

- MyHC

Myosin Heavy Chain

Footnotes

Portions of this material were presented at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 19, 2016

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose

References

- 1.Robbins J, Bridges AD, Taylor A. Oral, pharyngeal and esophageal motor function in aging. GI Motil Online. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robbins J, Levine R, Wood J, Roecker EB, Luschei E. Age effects on Lingual Pressure Generation as a Risk Factor for Dysphagia. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1995;50A:M257–62. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.5.m257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw DW, Cook IJ, Gabb M, Holloway RH, Simula ME, Panagopoulos V, et al. Influence of normal aging on oral-pharyngeal and upper esophageal sphincter function during swallowing. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1995;268:G389–G396. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.3.G389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer PM, Jaffe DM, McCulloch TM, Finnegan EM, Van Daele DJ, Luschei ES. Quantitative contributions of the muscles of the tongue, floor-of-mouth, jaw, and velum to tongue-to-palate pressure generation. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51:828–835. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/060). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaser AJ, Wang H, Volz LM, Connor NP. Biochemistry of the Anterior, Medial, and Posterior Genioglossus in the Aged Rat. Dysphagia. 2011;26:256–63. doi: 10.1007/s00455-010-9297-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki T, Connor NP, Lee K, Bless DM, Ford CN, Inagi K. Age-related Alterations in Myosin Heavy Chain Isoforms in Rat Intrinsic Laryngeal Muscles. Ann Orol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:962–7. doi: 10.1177/000348940211101102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishida N, Taguchi A, Motoyoshi K, Hyodo M, Gyo K, Desaki J. Age-related changes in rat intrinsic laryngeal muscles: analysis of muscle fibers, muscle fiber proteins, and subneural apparatuses. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:975–84. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Napadow VJ, Chen Q, Wedeen VJ, Gilbert RJ. Biomechanical basis for lingual muscular deformation during swallowing. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1999;277:G695–G701. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.3.G695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiiemae KM, Palmer JB. Tongue movements in feeding and speech. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:413–429. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kayalioglu M, Shcherbatyy V, Seifi A, Liu Z-J. Roles of intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles in feeding: electromyographic study in pigs. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:786–796. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailey EF. Coordination of intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles during spontaneous breathing in the rat. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:440–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00733.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behan M, Moeser AE, Thomas CF, Russell JA, Wang H, Leverson GE, et al. The Effect of Tongue Exercise on Serotonergic Input to the Hypoglossal Nucleus in Young and Old Rats. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2012;55:919. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/11-0091). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uemura-Sumi M, Itoh M, Mizuno N. The distribution of hypoglossal motoneurons in the dog, rabbit and rat. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1988;177:389–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00304735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClung JR, Goldberg SJ. Organization of motoneurons in the dorsal hypoglossal nucleus that innervate the retrusor muscles of the tongue in the rat. Anat Rec. 1999;254:222–230. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990201)254:2<222::AID-AR8>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLoon LK, Andrade F. Craniofacial Muscles: A New Framework for Understanding the Effector Side of Craniofacial Muscle Control. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granberg I, Lindell B, Eriksson P-O, Pedrosa-Domellöf F, Stål P. Capillary Supply in Relation to Myosin Heavy Chain Fibre Composition of Human Intrinsic Tongue Muscles. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;192:303–13. doi: 10.1159/000318645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connor NP, Ota F, Nagai H, Russell JA, Leverson G. Differences in Age-Related Alterations in Muscle Contraction Properties in Rat Tongue and Hindlimb. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51:818. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/059). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robbins J, Gangnon RE, Theis SM, Kays SA, Hewitt AL, Hind JA. The Effects of Lingual Exercise on Swallowing in Older Adults: LINGUAL EXERCISE AND SWALLOWING. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1483–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park T, Kim Y. Effects of tongue pressing effortful swallow in older healthy individuals. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogus-Pulia N, Rusche N, Hind JA, Zielinski J, Gangnon R, Safdar N, et al. Effects of Device-Facilitated Isometric Progressive Resistance Oropharyngeal Therapy on Swallowing and Health-Related Outcomes in Older Adults with Dysphagia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:417–24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeates EM, Molfenter SM, Steele CM. Improvements in tongue strength and pressure-generation precision following a tongue-pressure training protocol in older individuals with dysphagia: three case reports. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:735. doi: 10.2147/cia.s3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ota F, Connor NP, Konopacki R. Alterations in contractile properties of tongue muscles in old rats. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:799–803. doi: 10.1177/000348940511401010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagai H, Russell JA, Jackson MA, Connor NP. Effect of Aging on Tongue Protrusion Forces in Rats. Dysphagia. 2008;23:116–21. doi: 10.1007/s00455-007-9103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kletzien H, Russell JA, Leverson GE, Connor NP. Differential effects of targeted tongue exercise and treadmill running on aging tongue muscle structure and contractile properties. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114:472–81. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01370.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saito H, Itoh I. Three-dimensional architecture of the intrinsic tongue muscles, particularly the longitudinal muscle, by the chemical-maceration method. Anat Sci Int. 2003;78:168–176. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-7722.2003.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turturro A, Witt WW, Lewis S, Hass BS, Lipman RD, Hart RW. Growth curves and survival characteristics of the animals used in the Biomarkers of Aging Program. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:B492–B501. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.b492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conn PM. Handbook of Models for Human Aging. Academic Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stål P, Marklund S, Thornell L-E, De Paul R, Eriksson P-O. Fibre Composition of Human Intrinsic Tongue Muscles. Cells Tissues Organs. 2003;173:147–61. doi: 10.1159/000069470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott W, Stevens J, Binder–Macleod SA. Human skeletal muscle fiber type classifications. Phys Ther. 2001;81:1810–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bloemberg D, Quadrilatero J. Rapid Determination of Myosin Heavy Chain Expression in Rat, Mouse, and Human Skeletal Muscle Using Multicolor Immunofluorescence Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borrione AC, Zanellato AMC, Saggin L, Mazzoli M, Azzarello G, Sartore S. Neonatal myosin heavy chains are not expressed in Ni-induced rat rhabdomyosarcoma. Differentiation. 1988;38:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1988.tb00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiaffino S, Gorza L, Sartore S, Saggin L, Ausoni S, Vianello M, et al. Three myosin heavy chain isoforms in type 2 skeletal muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1989;10:197–205. doi: 10.1007/BF01739810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucas CA, Kang LHD, Hoh JFY. Monospecific Antibodies against the Three Mammalian Fast Limb Myosin Heavy Chains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;272:303–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azzarello G, Sartore S, Saggin L, Gorza L, D’andrea E, Chieco-Bianchi L, et al. Myosin isoform expression in rat rhabdomyosarcoma induced by Moloney murine sarcoma virus. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1987;113:417–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00390035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abd-El-Malek S. Observations on the morphology of the human tongue. J Anat. 1939;73:201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClung JR, Goldberg SJ. Functional anatomy of the hypoglossal innervated muscles of the rat tongue: a model for elongation and protrusion of the mammalian tongue. Anat Rec. 2000;260:378–386. doi: 10.1002/1097-0185(20001201)260:4<378::AID-AR70>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanders I, Mu L. A Three-Dimensional Atlas of Human Tongue Muscles: Human Tongue Muscles. Anat Rec. 2013;296:1102–14. doi: 10.1002/ar.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyawaki K. A Study on the Musculature of the Human Tongue. Annu Bull Res Inst Logop Phoniatr. 1974;8:23–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takemoto H. Morphological analyses of the human tongue musculature for three-dimensional modeling. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001;44:95–107. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith LR, Barton ER. SMASH–semi-automatic muscle analysis using segmentation of histology: a MATLAB application. Skelet Muscle. 2014;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pette D, Starton RS. Myosin isoforms, muscle fiber types, and trasitions. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;50:500–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20000915)50:6<500::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Briguet A, Courdier-Fruh I, Foster M, Meier T, Magyar JP. Histological parameters for the quantitative assessment of muscular dystrophy in the mdx-mouse. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14:675–82. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saigusa H, Yamashita K, Tanuma K, Saigusa M, Niimi S. Morphological studies for retrusive movement of the human adult tongue. Clin Anat. 2004;17:93–8. doi: 10.1002/ca.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stettner GM, Rukhadze I, Mann GL, Lei Y, Kubin L. Respiratory modulation of lingual muscle activity across sleep–wake states in rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;188:308–17. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kays SA, Hind JA, Gangnon RE, Robbins J. Effects of dining on tongue endurance and swallowing-related outcomes. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2010;53:898–907. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/09-0048). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hagino H, Kataoka H, Osaki M, Hiramatsu Tetsuya. Effect of aging on oral and swallowing function after meal consumption. Clin Interv Aging. 2015:229. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S75211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakayama M. Histological study on aging changes in the human tongue. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 1991;94:541–55. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.94.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rother P, Wohlgemuth B, Wolff W, Rebentrost I. Morphometrically observable aging changes in the human tongue. Ann Anat - Anat Anz. 2002;184:159–64. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(02)80011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Connor NP, Russell JA, Wang H, Jackson MA, Mann L, Kluender K. Effect of tongue exercise on protrusive force and muscle fiber area in aging rats. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52:732–744. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/08-0105). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Connor NP, Russell JA, Jackson MA, Kletzien H, Wang H, Schaser AJ, et al. Tongue muscle plasticity following hypoglossal nerve stimulation in aged rats. Muscle Nerve. 2013;47:230–40. doi: 10.1002/mus.23499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sokoloff AJ, Douglas M, Rahnert JA, Burkholder T, Easley KA, Luo Q. Absence of morphological and molecular correlates of sarcopenia in the macaque tongue muscle styloglossus. Exp Gerontol. 2016;84:40–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pittman LJ, Bailey EF. Genioglossus and Intrinsic Electromyographic Activities in Impeded and Unimpeded Protrusion Tasks. J Neurophysiol. 2008;101:276–82. doi: 10.1152/jn.91065.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Polla B. Respiratory muscle fibres: specialisation and plasticity. Thorax. 2004;59:808–17. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.009894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]