Abstract

Distant metastases are relatively common in breast cancer, but spread to the head and neck region is uncommon and can be diagnostically challenging. Pathology databases of two academic hospitals were searched for patients. The diagnoses were by morphologic comparison with the primary breast specimen (when available) or through the use of immunohistochemical stains characteristic of breast carcinoma (cytokeratin 7, mammaglobin, GCDFP15, and/or GATA3 positive—excluding new primary tumors at the respective head and neck sites). Of the 25 patients identified, only 22 (88.0 %) had a known history of breast carcinoma. Time from primary diagnosis to head and neck metastasis was highly variable, ranging from 1 to 33 years (mean = 10.9 years). The most common locations were neck lymph nodes (8 cases), orbital soft tissue (5), oral cavity (3), skull base (3), mastoid sinus (2), nasal cavity (1), palatine tonsil (1), and facial skin (1). Clinical presentations were highly variable, ranging from cranial nerve palsies without a mass lesion to oral cavity erythema and swelling to bone pain. Histologically, two cases showed mucosal (or skin)-based mass lesions with associated pagetoid spread in the adjacent epithelium, a feature normally associated with primary carcinomas. Three tumors were misdiagnosed pathologically as new head and neck primary tumors. This series demonstrates the extreme variability in clinical and pathologic features of breast cancer metastatic to the head and neck, including long time intervals to metastasis.

Keywords: Metastatic, Breast, Carcinoma, Head, Neck

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in women in the United States. Although distant metastases are relatively common in breast cancer, spread to the head and neck region is uncommon and can be diagnostically challenging [1]. Since the literature on this subject mainly consists of case reports [1–3], in this study we sought to describe the clinical and pathologic features in a series of patients with breast carcinoma metastatic to the head and neck region from two academic hospitals and to describe many of the extremely unusual clinical and pathologic features that can be seen.

Methods

Pathology databases of two academic hospitals were searched for breast cancer metastases to the head and neck region by keyword searches of pathology electronic databases and by identification of patients in routine clinical practice. The Washington University database was searched from 1989 until 2015 (26 years), and the Vanderbilt University database from 2005 until 2016 (11 years). Cases of brain parenchymal metastasis were excluded. The diagnoses were made by morphologic comparison with the primary breast specimen (when available) or through the use of immunohistochemical (IHC) stains characteristic of breast carcinoma (and in order to exclude new primary tumors at the respective sites). Two authors (DDG, RDC) independently reviewed cases from Washington University in St. Louis, and one author (JSL) reviewed cases from Vanderbilt University. A chart review of all patients was performed to gather clinically relevant characteristics such as age at diagnosis of head and neck metastasis, clinical presentation, interval time between primary breast cancer diagnosis and metastasis to the head and neck region, treatment, and clinical diagnoses.

Results

A total of 25 patients were identified. The clinical and demographic features are listed in Table 1. All patients were female, and the average age at diagnosis of head and neck metastasis was 61 years (range 39–92 years). Of these patients 22 (88%) had a known history of breast carcinoma. In the remaining 3 patients (12%), the head and neck metastases were the patients’ first diagnostic specimen. For the patients who developed metastases after initial diagnosis of their breast carcinomas, the time from primary diagnosis to head and neck metastasis ranged from 1 to 33 years (mean = 10.9 years). The most common locations were neck lymph nodes (8 patients) and orbital soft tissue (5), followed by oral cavity (3), skull base (3), mastoid sinus (2), nasal cavity (1), palatine tonsil (1), facial skin (1), and paratracheal soft tissue (1). Of the 23 patients with prior pathologic and clinical data available for review, 16 (64%) patients had other known metastases before the diagnosis of head and neck metastasis. As would be expected, axillary nodal metastases were the most common, followed by bone metastases. Clinical presentations were highly variable, ranging from cranial nerve palsies without a mass lesion, to oral cavity erythema and swelling, to bone pain. Two patients presented with neck masses clinically thought to be metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma or to be parathyroid tissue. Two patients presented with cranial neuropathies related to skull base lesions. Two presented with gingival-based masses mimicking primary mucosa carcinomas. One patient presented with a clival/skull base mass thought to be a new primary sarcoma.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathologic features of the patients with breast carcinoma metastases to the head and neck

| Case | Age at diagnosis of metastasis | Site | Clinical presentation | Clinical suspicion | Histologic type | Interval from primary to metastasis (years) | Other known metastases before HN metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 47 | Bilateral palatine tonsils | Bilateral tonsil FDG uptake on PET scan | Metastatic breast carcinoma | Pagetoid carcinoma | 7.3 | Axillary lymph node |

| 2 | 81 | Paratracheal soft tissue | Hyperparathyroidism; surgically identified paratracheal mass | Parathyroid hyperplasia | Ductal carcinoma | 22 | Bone |

| 3 | 45 | Nasal cavity | Epistaxis | Primary squamous cell carcinoma versus metastasis | Mucinous carcinoma | 6.3 | Axillary lymph node, pancreas, bone, liver and lung |

| 4 | 53 | Mastoid sinus | Headache/hearing loss/loss of taste on ipsilateral tongue | Metastatic breast carcinoma | Ductal carcinoma | 3.2 | Axillary lymph node, bone |

| 5 | 79 | Mastoid sinus | Not available | Not available | Adenocarcinoma* | N/A | N/A |

| 6 | 92 | Skin face | Chin mass | Primary skin cancer | Lobular carcinoma | Primary diagnosis | None |

| 7 | 53 | Skull base | Rising tumor markers | Metastatic breast carcinoma | Mucinous carcinoma | 9 | Axillary lymph node |

| 8 | 48 | Skull base | Right sided facial pain, tingling, numbness | Malignancy versus atypical infection | Carcinoma with lobular features | Primary diagnosis | None |

| 9 | 39 | Oral cavity | Edematous, painful hypertrophic gingiva | Metastatic breast cancer | Ductal carcinoma | 10.8 | Axillary lymph node, liver and bone |

| 10 | 52 | Oral cavity | Edematous and erythematous gingiva and right RMT | Primary head and neck mucosal-based carcinoma | Pagetoid carcinoma | 5.3 | Axillary lymph node |

| 11 | 78 | Oral cavity | Buccal mass | Primary head and neck tumor of minor salivary glands | Lobular carcinoma | 18 | None |

| 12 | 49 | Orbital soft tissue | Orbital soft tissue mass | Not available | Lobular carcinoma | 7.1 | Bone, ovary and pleural fluid |

| 13 | 61 | Orbital soft tissue/ethmoid and maxillary sinus | Nasal airway obstruction and pain/headache/blurry vision | Metastatic breast carcinoma | Ductal carcinoma | 1 | Axillary lymph node |

| 14 | 75 | Orbital soft tissue | Lacrimal sac mass | Not available | Lobular carcinoma | 5 | Bone |

| 15 | 58 | Orbital soft tissue | Lower eyelid mass | Lymphoma versus metastatic carcinoma versus sarcoid | Lobular carcinoma | Primary diagnosis | Possible axillary lymph node by imaging |

| 16 | 80 | Orbital soft tissue | Diplopia | Lymphoma versus inflammatory pseudotumor | Lobular carcinoma | 33 | None |

| 17 | 61 | Neck lymph node | Left supraclavicular LAD | Metastatic breast carcinoma | Lobular carcinoma | 13 | Bone |

| 18 | 52 | Neck lymph node | Left neck LAD | Metastatic breast carcinoma | Ductal carcinoma | 2.1 | Axillary lymph node, lung, liver, chest wall and bone |

| 19 | 55 | Neck lymph node | Left neck level II LAD | Metastatic breast carcinoma | Ductal carcinoma | N/A | N/A |

| 20 | 49 | Neck lymph node | Painful left neck LAD involving brachial plexus | Metastatic breast carcinoma | Ductal carcinoma | 10.3 | Axillary and hilar lymph node, lung and bone |

| 21 | 76 | Neck lymph node | Left neck LAD, hoarse voice | Metastatic carcinoma | Lobular carcinoma | 9 | Axillary lymph node |

| 22 | 61 | Neck lymph node | Not available | Not available | Ductal carcinoma | 7 | Axillary lymph node |

| 23 | 66 | Neck lymph node | Left neck LAD | Metastatic carcinoma versus lymphoma | Ductal carcinoma | 11 | None |

| 24 | 44 | Neck lymph node | Right neck LAD | Metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma | Ductal carcinoma | 11 | None |

| 25 | 79 | Skull Base/Clivus | Headaches | Chondrosarcoma | Ductal carcinoma | 28 | None |

RMT retromolar trigone, LAD lymphadenopathy, HN head and neck

* Histologic type not further classified due to crush artifact

All patients had either comparison with the prior breast carcinoma specimen(s) or positive immunohistochemistry for breast specific markers (such as GDCFP15, mammaglobin, and/or GATA3, Table 2). All receptor studies were congruent with the prior breast carcinoma specimens. Histologically, 11 (44%) were ductal carcinoma (or carcinoma, no special type), 9 (36%) lobular carcinoma, 2 (8%) mucinous carcinoma, and 1 (4%) simply classified as “adenocarcinoma” due to crush artifact which precluded further morphologic classification. The remaining two patients showed only mucosal-based lesions with pagetoid tumor cell spread through the epithelium (Fig. 1), a feature normally associated with primary carcinomas. Further, one patient had an oral cavity-based mucosal mass lesion associated with cervical nodal metastases, thus clinically and pathologically mimicking a primary head and neck tumor.

Table 2.

Pathologic features of the patients with breast carcinoma metastases to the head and neck

| Case | Site | Histologic type | Positive immunostains | Negative immunostains | Breast receptor studies in metastatic specimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bilateral palatine tonsils | Pagetoid carcinoma | CK7, GCDFP-15 | N/A | ER (−) |

| 2 | Paratracheal soft tissue | Ductal carcinoma | GATA3, panCK,AR | Synaptophysin | ER (+), PR unk, Her2 unk |

| 3 | Nasal cavity | Mucinous carcinoma | GATA3 | TTF-1, CDX2, mammaglobin, GCDFP-15 | ER (+), PR (−) |

| 4 | Mastoid sinus | Ductal carcinoma | CK7 | Synaptophysin, chromogranin | ER (+) |

| 5 | Mastoid sinus | Adenocarcinoma* | N/A | N/A | ER (+), PR (+) |

| 6 | Skin face | Lobular carcinoma | CK7 | Mammaglobin, P63, BerEP4 | ER (+),PR (+), Her-2 (−) |

| 7 | Skull base | Mucinous carcinoma | CK7 | CK20 | ER (+), PR (−), Her-2 (+) |

| 8 | Skull base | Carcinoma with lobular features | GATA3, AR, CK7 | GCDFP-15, synaptophysin, chromogranin, P40 | ER (+), PR (+), Her-2 (−) |

| 9 | Skull base/clivus | Ductal carcinoma | panCK, GATA3 | P40, S-100, PAX8, SOX10, TTF-1 | ER (+), PR (+), Her-2 (−) |

| 10 | Oral cavity | Ductal carcinoma | N/A | N/A | Her-2 (−) |

| 11 | Oral cavity | Pagetoid carcinoma | CK7 | GCDFP-15 | Her-2 (−) |

| 12 | Oral cavity | Lobular carcinoma | panCK, CK7 | CK20 | ER (+), PR (+), Her-2 unk |

| 13 | Orbital soft tissue | Lobular carcinoma | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 14 | Orbital soft tissue/ethmoid and maxillary sinus | Ductal carcinoma | CK7 | CK20, BCA-225 | N/A |

| 15 | Orbital soft tissue | Lobular carcinoma | N/A | N/A | ER (+), PR (+), Her-2 (−) |

| 16 | Orbital soft tissue | Lobular carcinoma | CK7 | CK20 | ER (+), PR (−) |

| 17 | Orbital soft tissue | Lobular carcinoma | GATA3, panCK | CD45 | ER (+), PR weak (+), Her-2 (−) |

| 18 | Neck lymph node | Lobular carcinoma | N/A | GCDFP-15, synaptophysin, chromogranin | ER (+), PR (+), Her-2 (−) |

| 19 | Neck lymph node | Ductal carcinoma | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 20 | Neck lymph node | Ductal carcinoma | Mammaglobin, CK7 | GCDFP-15, CK20 | ER (+), PR (−), Her-2 (+) |

| 21 | Neck lymph node | Ductal carcinoma | N/A | N/A | ER (+), PR (+), Her-2 (+) |

| 22 | Neck lymph node | Lobular carcinoma | Mammaglobin, GCDFP-15 (focal +), panCK | N/A | N/A |

| 23 | Neck lymph node | Ductal carcinoma | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 24 | Neck lymph node | Ductal carcinoma | N/A | N/A | ER (+), PR (+), Her-2 (−) |

| 25 | Neck lymph node | Ductal carcinoma | GATA3 | TTF-1 | ER (+), PR (−), Her-2 (equiv) |

* Histologic type not further classified due to crush artifact

panCK pan cytokeratin, CK7 cytokeratin 7, CK20 cytokeratin 20, GCDFP-15 gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, ER estrogen receptor, PR progesterone receptor, unk unknown, equiv equivocal

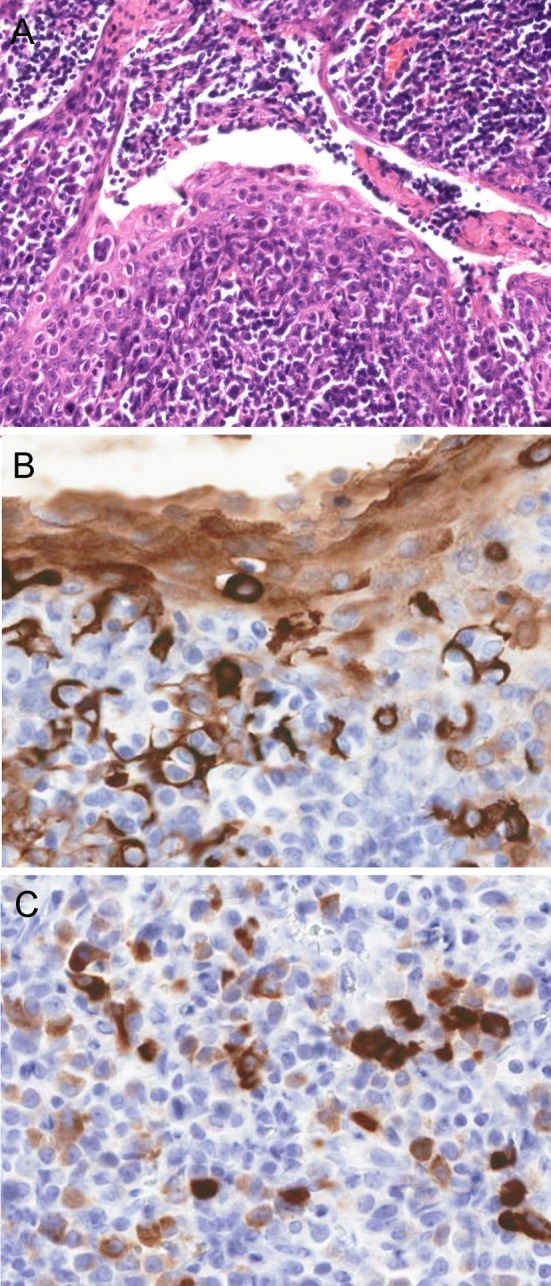

Fig. 1.

a H&E section showing pagetoid infiltration of tonsillar crypt epithelium by tumor cells (arrows). b Cytokeratin 7 and c GCDFP-15 immunostains are strongly positive, showing the tumor cells infiltrating the epithelium and extending into the underlying lymphoid tissue. (a 10× magnification; b, c 20× magnification)

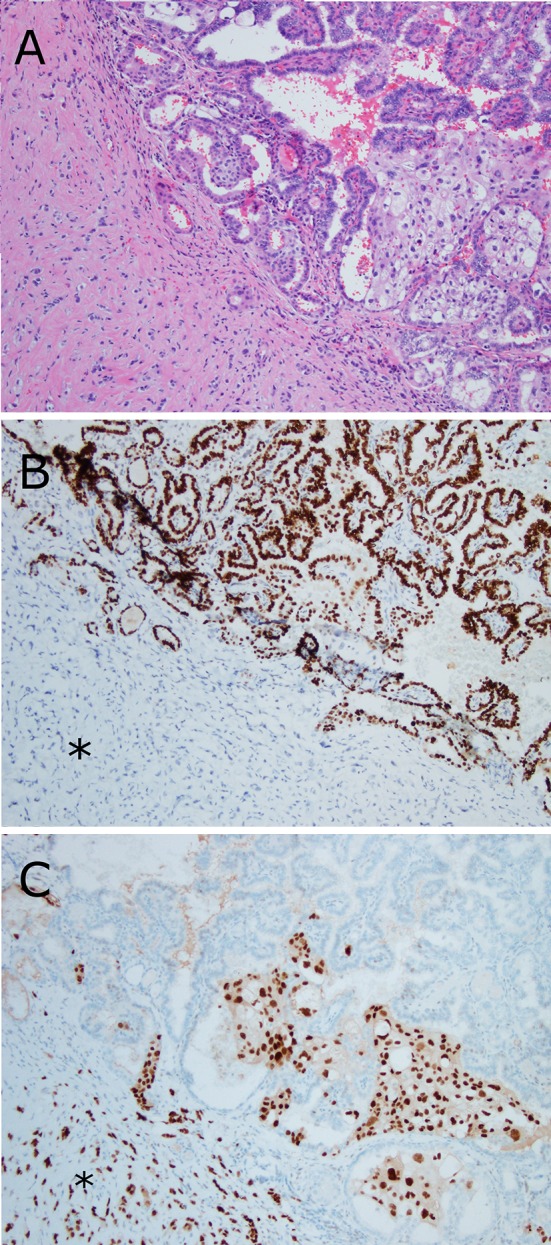

The original diagnoses are listed in Table 1. In total, only 11 (44%) of the patients were clinically suspected specifically as having metastatic breast carcinoma prior to biopsy or resection. Three (12%) of the patients were diagnosed pathologically as having new primary tumors in the head and neck before later being corrected as being metastatic breast carcinoma. The patient with a facial skin tumor was initially misdiagnosed pathologically as having basal cell carcinoma, and one of the oral cavity tumor patients was diagnosed pathologically with primary head and neck adenosquamous carcinoma. One unusual case presented as a 300 g paratracheal mass suspicious for parathyroid adenoma in a patient with hyperparathyroidism. This mass was sent for frozen section analysis and was actually diagnosed intraoperatively as “hypercellular parathyroid tissue”, despite later being proven to be metastatic breast carcinoma. Finally, one patient underwent surgery for recurrent papillary thyroid carcinoma, and pathologically had a roughly even admixture of metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma and surrounding and interspersed, clinically unsuspected, metastatic breast carcinoma in their neck nodes and paratracheal soft tissue (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Metastatic breast carcinoma mixed with metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma in a neck lymph node. a Metastatic breast carcinoma cells infiltrate the stroma (asterisk) and also extend between the papillary fronds of papillary thyroid carcinoma. b A TTF-1 immunohistochemical stain highlights the tumor cells of the thyroid cancer. c An estrogen receptor immunohistochemical stain highlights the breast cancer cells (asterisk) (all figures 10× magnification)

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women and accounts for a large proportion of cancer deaths. Metastatic breast cancer is still unlikely to be cured despite the introduction of newer systemic therapies in the last years [4]. The 5-year survival rate decreases dramatically from locally advanced disease with regional lymph node involvement (85%) to distant metastasis (25%) [5]. However, breast cancer progression can be gradual, and the introduction of more effective and targeted treatments for women with distant metastases has helped to slow the progression so that patients live longer with distant metastatic disease and are at risk of metastases to different or unusual anatomic sites so that head and neck metastases are not infrequently seen.

Breast carcinoma is amongst the most common tumors to metastasize to the head and neck. In large series, it constitutes ~15–20% of all metastases to this region [1–3, 6, 7] and accounts for the majority of orbital soft tissue and temporal bone metastases [1–3, 6–11]. It has been described in almost every head and neck anatomic subsite and is amongst the more common tumors to metastasize to the sinonasal tract, major salivary glands, oral cavity, thyroid gland, oro- and hypopharynx, and craniofacial bones [12–16]. However, since metastases to the head and neck are uncommon to begin with, breast carcinoma metastases are still relatively rare in clinical practice. This series identified 25 patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest case series on this subject. It demonstrates that metastases to the head and neck region can be the presenting lesions for patients with metastatic breast carcinoma, can occur many years after the original diagnosis, and can be extremely challenging for clinicians and pathologists alike to diagnose. Further, this study demonstrates the importance of recognizing its many unusual presentations (Table 3). The latter is becoming even more challenging in this era of practice subspecialization. Many head and neck pathologists, particularly at academic institutions or in very large practice groups, may have seen little breast pathology in training or in clinical practice, yet are expected to recognize it when it presents in the head and neck region. Head and neck pathologists must be familiar with the clinical history and must be keenly aware of the possible disease patterns and presentations when confronted with carcinomas of the head and neck in female patients.

Table 3.

Unusual pathologic features seen in breast metastases to the head and neck region

| High proportion of lobular carcinoma amongst orbital soft tissue metastases |

| Skull base perineural carcinoma causing neurologic symptoms in the absence of a mass lesion |

| Pagetoid spread of metastatic tumor cells in oral and oropharyngeal mucosa |

| Prominent mucinous component in metastases despite little or no mucin production in primary lesion |

| Mucosal-based carcinoma with regional cervical adenopathy, mimicking a new primary head and neck lesion |

One of the most noteworthy features is the long time interval between the primary diagnosis and metastasis to the head and neck region in patients with established disease [4]. For the 20 patients with established history of breast carcinoma, 16 (80%) presented with their head and neck metastasis 5 or more years after their primary diagnosis, with nine presented with them after 10 or more years. Only four (20 %) presented with their head and neck metastasis within the first 5 years after primary diagnosis. The mean interval was 10.9 years, with the longest being 33 years. Long interval metastasis to bone and other organs such as lung and brain is not a new concept in breast cancer [4, 5], especially to breast pathologists. Our findings show that this feature also applies to metastases to the head and neck region. It is also pertinent to point out, however, that head and neck metastases can be the first diagnostic specimen. This was the case with three patients in the current series (patients 6, 8, and 16 in Table 1). Two of them had subsequent breast biopsies showing the primary tumor. One patient (number 6 in Table 1), had metastasis to her facial skin, but no primary breast lesion could be identified clinically or by imaging. Many unusual clinical features can be seen. Tumors can present in bone as lytic lesions mimicking primary bone tumors (patient 9), as salivary gland (patient 12), skin (patient 6), or sinonasal masses mimicking new primaries (patient 3), or as cranial nerve palsies in the absence of a mass lesion, with only thickening of the skull base soft tissues (including along nerves) (patient 8). They can present as neck masses mimicking lymphoma (patient 24), or even as possible parathyroid glands (patient 2).

Several unusual pathologic features can be seen. One of these is an apparent predilection of lobular carcinoma metastases to the orbital soft tissues. Breast carcinoma is the most common tumor to metastasize to the orbital soft tissues [1, 9]. Although lobular carcinoma only accounts for approximately 10–15% of all mammary carcinomas in general, four out of five (80%) of the purely lobular carcinomas in our series had metastases to the orbital soft tissue. Previous studies have also noted this tendency. Raap et al. [8] described eight cases of breast carcinoma metastases to the orbit, seven of which (88%) had lobular morphology (8), and reviewed the literature to confirm this tendency. Whether there is a tropism of lobular cancer cells to the orbital tissue or this is purely due to the more infiltrative nature of this tumor type along with its general tendency for spreading to myriad body sites is a matter of speculation.

Different histologic features between the primary lesion and metastases can sometimes confound the pathologist. There were three patients in our series with prominent mucinous components in the metastases and little or no mucin present in the primary lesions. These three patients had metastases with morphologic and immunohistochemical findings consistent with breast cancer so the lesions logically must be from the same primary breast tumor. This again highlights a potential diagnostic pitfall—the presence of a mucinous component or other different morphologic pattern between the primary breast tumor and the head and neck lesions, which should not rule out spread from the breast primary.

Pagetoid spread of tumor cells through an originating (or adjacent) mucosa or skin surface is a hallmark feature of certain carcinomas and largely is assumed to be an indication that the tumor has arisen in the region. This is quite unusual in the head and neck, but has been described in the oral cavity from salivary gland tumors [17] and in skin from various tumors such as apocrine (signet ring cell) carcinomas [18]. However, the finding of pagetoid spread in the head and neck mucosa in two patients in this series (palatine tonsillar crypts and oral cavity mucosa) shows that distant metastases can show pagetoid spread through mucosal surfaces in the metastases even without a dominant mass lesion and without any adjacent tumor in the submucosa or surrounding tissues.

Another feature normally suggestive of a primary tumor is the presence of regional lymphadenopathy. Distant metastases to organs such and lung and liver can have associated regional lymph node metastases, but this is very infrequent. For some patients with metastatic breast carcinoma to the head and neck, there can be a dominant mass lesion and positive regional lymph nodes, mimicking a new primary tumor, as was the case with patient 12.

Certainly, there are other presentations and pathologic findings in metastatic breast cancer to the head and neck that weren’t seen in this series. Parenchymal metastases to the submandibular and parotid glands can be difficult to distinguish from new primary tumors arising there, specifically salivary duct carcinoma [1]. The latter is androgen receptor and GATA3 positive and frequently expresses Her2 [19], but is typically negative for estrogen and progesterone receptors. There are metastases to the thyroid gland from breast carcinoma [1], but these are much easier to discern as non-primary lesions with morphology and immunohistochemistry. Thyroid primary carcinomas are morphologically different, and immunohistochemistry is very clear cut—thyroid carcinomas are PAX8, TTF-1, and thyroglobulin positive. Metastatic breast carcinomas are negative for all of these, and thyroid carcinomas are negative for all of the breast markers including almost always being negative for GATA3 [20].

Conclusion

This series demonstrates the extreme variability in clinical and pathologic features of breast cancer metastatic to the head and neck. Many of the cases were initially misdiagnosed as primary head and neck lesions, emphasizing the difficulty. Lack of a known breast cancer diagnosis, the presence of pagetoid spread in the head and neck epithelium, and cervical adenopathy that appears to be associated with a primary head and neck mucosal-based lesion do not exclude a diagnosis of metastatic breast carcinoma. Furthermore, the interval between diagnosis and metastasis can be extremely long (average 9 years, maximum 33 years). When faced with unusual adenocarcinomas in the head and neck region, clinicians and pathologists must be keenly aware of the spectrum of findings that can be seen with metastases from breast carcinoma, so that these patients can be correctly diagnosed and treated.

Footnotes

This work was presented at the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology annual meeting in Seattle, WA on March 14, 2016.

References

- 1.Barnes L. Metastases to the head and neck: an overview. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3(3):217–224. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0123-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadri D, Azizi A, Farhadi S, Shokrgozar H, Entezari N. Head and neck metastatic tumors: a retrospective survey of Iranian patients. J Dent. 2015;16(1):17–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Servato JP, de Paulo LF, de Faria PR, Cardoso SV, Loyola AM. Metastatic tumours to the head and neck: retrospective analysis from a Brazilian tertiary referral centre. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42(11):1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guth U, Magaton I, Huang DJ, Fisher R, Schotzau A, Vetter M. Primary and secondary distant metastatic breast cancer: two sides of the same coin. Breast. 2014;23(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YT. Patterns of metastasis and natural courses of breast carcinoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1985;4(2):153–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00050693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClure SA, Movahed R, Salama A, Ord RA. Maxillofacial metastases: a retrospective review of one institution’s 15-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(1):178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thiele OC, Freier K, Bacon C, Flechtenmacher C, Scherfler S, Seeberger R. Craniofacial metastases: a 20-year survey. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39(2):135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raap M, Antonopoulos W, Dammrich M, Christgen H, Steinmann D, Langer F, et al. High frequency of lobular breast cancer in distant metastases to the orbit. Cancer Med. 2015;4(1):104–111. doi: 10.1002/cam4.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shields JA, Shields CL, Brotman HK, Carvalho C, Perez N, Eagle RC., Jr Cancer metastatic to the orbit: the 2000 Robert M. Curts Lecture. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17(5):346–354. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200109000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Waal RI, Buter J, van der Waal I. Oral metastases: report of 24 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41(1):3–6. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(02)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson EG, Hinojosa R. Histopathology of metastatic temporal bone tumors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117(2):189–193. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870140077010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayon R, Banas SK, Wenig BL. Case report: metastatic breast cancer presenting as a hypopharyngeal mass. Ear Nose Throat J. 2013;92(3):E5–E6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell JO, Yan K, Burkey B, Scharpf J. Nonthyroid metastasis to the thyroid gland: case series and review with observations by primary pathology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0194599816655783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirshberg A, Buchner A. Metastatic tumours to the oral region. An overview. Eur J Cancer Part B Oral Oncol. 1995;31B(6):355–360. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(95)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirshberg A, Leibovich P, Buchner A. Metastases to the oral mucosa: analysis of 157 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22(9):385–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1993.tb00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirshberg A, Shnaiderman-Shapiro A, Kaplan I, Berger R. Metastatic tumours to the oral cavity—pathogenesis and analysis of 673 cases. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(8):743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theaker JM. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the oral mucosa with in situ carcinoma of minor salivary gland ducts. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12(11):890–895. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198811000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwaya M, Uehara T, Yoshizawa A, Kobayashi Y, Momose M, Honda T, et al. A case of primary signet-ring cell/histiocytoid carcinoma of the eyelid: immunohistochemical comparison with the normal sweat gland and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34(8):e139–e145. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182590ec1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornolti G, Ungari M, Morassi ML, Facchetti F, Rossi E, Lombardi D, et al. Amplification and overexpression of HER2/neu gene and HER2/neu protein in salivary duct carcinoma of the parotid gland. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(10):1031–1036. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.10.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miettinen M, McCue PA, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Rys J, Czapiewski P, Wazny K, et al. GATA3: a multispecific but potentially useful marker in surgical pathology: a systematic analysis of 2500 epithelial and nonepithelial tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(1):13–22. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182a0218f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]