Abstract

We used data from the mandatory statewide Rhode Island (RI) Health Information Technology (HIT) Survey to characterize office-based PCPs’ adoption and use of EHRs from 2009–2014. We found accelerated adoption of EHRs in the five years since state and federal incentive programs began targeting PCPs’ adoption of HIT. There was room for improvement, however; for example, when asked to indicate the proportion of patients with whom they used various functionalities, only 13.4% of office-based PCPs said they “almost always” communicated with patients using secure messaging and 22.3% “almost always” used secure clinical messaging with outside providers. Results suggest uneven use of EHR functionalities, with low rates and slower uptake in some areas. These findings highlight opportunities to increase use of functionalities related to improved patient care and quality-based payment models.

Keywords: Health information technology, electronic health records, primary care physician, quality, meaningful use

INTRODUCTION

Electronic health records (EHRs) may reduce medical errors, increase adherence to clinical guidelines, and improve efficiency and care coordination.1 Policy efforts to increase EHR use have focused on primary care physicians (PCPs), since PCPs often represent patients’ first point of contact with the healthcare system and are responsible for preventive and chronic disease management.

The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act created Medicare and Medicaid EHR incentive payment programs targeting PCPs.2 By 2012, nearly three-quarters of office-based physicians reported having EHRs, a twofold increase since 2007, but only 18% of all office-based physicians met requirements to qualify for federal incentives.3 Despite increased adoption of EHRs, gaps remain in the use of functionalities that may improve patients’ experience and care coordination, such as providing patients access to their records, sending summary-of-care documents, and securely transmitting information between providers.4

Capitalizing on EHRs’ potential requires understanding which functionalities PCPs use and why. In 2008, the Rhode Island Department of Health became the first state to require all practicing physicians to respond to an annual survey about their health information technology (HIT) adoption. In this analysis, we use the Rhode Island (RI) HIT Survey to characterize how RI PCPs use EHRs and to examine trends in the use of specific functionalities over time.

METHODS

Sample

The RI HIT Survey targets all licensed independent practitioners (LIPs), including physicians, licensed in RI, in active practice, and providing direct patient care in RI or an adjacent state. We classified respondents as PCPs if they were office-based physicians who identified their specialty as: internal medicine (general), geriatrics, family medicine, or pediatrics. We classified respondents as hospital- or office-based based on their self-reported main practice location. This analysis was limited to PCPs in active practice.

Survey Instrument and Administration

The Department of Health’s efforts to create the RI HIT survey with its quality reporting contractor, Healthcentric Advisors, are described elsewhere,5 but the instrument draws upon efforts in Massachusetts6 and nationally.7 It was piloted in 2008 and is updated annually to incorporate feed-back and reflect changes in HIT and related policy. Results have been publicly reported annually since 2009.8

The survey aims to measure not only the presence or absence of an EHR, but LIPs’ use of EHRs. To do so, it asks respondents to indicate how often they use EHR functionalities in eight domains: demographics, clinical documentation, decision support, interoperability, order management, patient support, reporting, and results management. It also asks about use of RI’s health information exchange, CurrentCare, and prescription monitoring program, a database of controlled substance prescriptions filled at the state’s pharmacies. Respondents indicate the percentage of patients with whom they use each specific EHR functionality and program: “Don’t Have,” “0% of patients” (Never), “<30% of patients” (Sometimes), “30–60% of patients” (Often), and “>60% of patients” (Almost Always). We reference the labels “never,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “almost always.”

In 2014, the RI HIT Survey was administered electronically (via SurveyMonkey) from April–June. All physicians with active RI licenses received mailed notices; the subset with available email addresses also received an email notification and up to two reminders. The survey incorporated skip patterns that excluded respondents who did not meet eligibility criteria and limited questions to those relevant to each respondent.

Data Analysis

We obtained a dataset with merged survey and licensure data for 2009–2014 under a data use agreement. Because these data do not contain any identifiers, the Brown University Institutional Review Board determined that this analysis did not constitute human subjects research.

We conducted all analyses using STATA 13 (College Station, TX). For descriptive analyses of 2014 data, we stratified responses by the presence or absence of an EHR in the respondents’ main practice and defined an EHR as “an integrated electronic information system that tracks patient health data, and may include such functions as visit notes, prescriptions, lab orders, etc.” For longitudinal analyses of 2009–2014 data, we chose “almost always” to capture physicians’ routine use of various EHR functionalities in typical practice and a cutoff of 40% to identify physicians who consistently interact with Medicaid and uninsured patients.

RESULTS

In 2014, the response rate was 62.3% among all physicians and 89.5% among all PCPs; this includes 698 office-based PCPs, our population of interest (Table 1). Within this population, use of EHRs was higher among those <60 years old and in practices with ≥5 clinicians; it did not vary considerably by the proportion of Medicaid or uninsured patients. 89.5% of PCPs reported having an EHR in 2014, up from 25.1% in 2009. The largest growth occurred between 2009 and 2010, when rates of EHR use increased from 25.1% of PCPs to 72.5%.

Table 1.

Office-Based Primary Care Physician Respondents’ Characteristics, 2014 (N=698)

| With EHRs* (N=625) |

Without EHRs (N=73) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

| Age, years | ||

| <44 | 159 (25.4) | 7 (9.6) |

| 45–59 | 308 (49.3) | 21 (28.8) |

| ≥60 | 158 (25.3) | 45 (61.6) |

| Practice size† | ||

| <5 clinicians | 276 (44.3) | 64 (88.9) |

| 5–10 clinicians | 205 (32.9) | 6 (8.3) |

| >10 clinicians | 142 (22.8) | 2 (2.8) |

| Use of e-prescribing | 579 (92.6) | 11 (15.1) |

| Patient population | ||

| ≥40% Medicaid | 164 (26.2) | 15 (20.6) |

| ≥40% uninsured | 59 (9.4) | 6 (8.2) |

Defined by question, “Does your main practice have EHR components? By ‘EHR components,’ we mean an integrated electronic information system that tracks patient health data, and may include such functions as visit notes, prescriptions, lab orders, etc. (This is also known as an electronic medical record or EMR.)”

Defined by question, “Altogether, approximately how large is your main practice? Please consider physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.”

The vast majority of PCPs (~90%) reported using patient demographics, clinical documentation, and drug interaction warning functionalities “almost always” (Table 2). A large majority (>70%) also reported using lab and radiology order entry functionalities “almost always.” Adoption of other functionalities was lower; only 13.4% and 22.3% “almost always” communicated with patients using secure messaging and used clinical messaging with outside providers, respectively.

Table 2.

Percentage of Office-Based Primary Care Physicians Using EHR Functionalities “Almost Always,” 2014 (N=625)*

| Functionality | Use “Almost Always” |

|---|---|

| Patient demographics | 582 (94.2) |

| Clinical documentation | |

| Write visit notes | 569 (91.3) |

| Document patient medications | 585 (94.1) |

| Document problem lists | 573 (92.1) |

| Order management | |

| Lab order entry | 470 (75.6) |

| Radiology order entry | 445 (71.5) |

| Results management | |

| Results direct from lab | 401 (64.5) |

| Scan paper lab results | 215 (34.8) |

| Radiology results direct from facility | 294 (47.3) |

| Scan paper radiology reports | 247 (40.0) |

| Interoperability | |

| Generate referrals | 430 (69.5) |

| Clinical messaging to outside providers | 138 (22.3) |

| Generate clinical summaries for referrals/transfers | 384(61.8) |

| Decision support | |

| Drug interaction warnings | 554 (89.1) |

| Reminders of indicated/overdue care | 335 (53.8) |

| Recommended care prompts | 312 (50.2) |

| Identify patients with condition or risk factor | 325 (52.9) |

| Patient support tools | |

| Accept prescription refill requests | 503 (83.1) |

| Communicate with patients with secure messaging | 82 (13.4) |

| Provide patient-specific-educational resources | 194 (31.1) |

| Provide patients with test results | 251 (40.6) |

| Schedule patient appointments | 407 (66.8) |

| Provide clinical summaries to patients | 412 (66.6) |

| Reporting | |

| Report clinical quality measures | 377 (60.8) |

| Identify patients out of compliance with guidelines | 323 (52.1) |

Due to missing data, the denominator varies by question and ranges from 605–623.

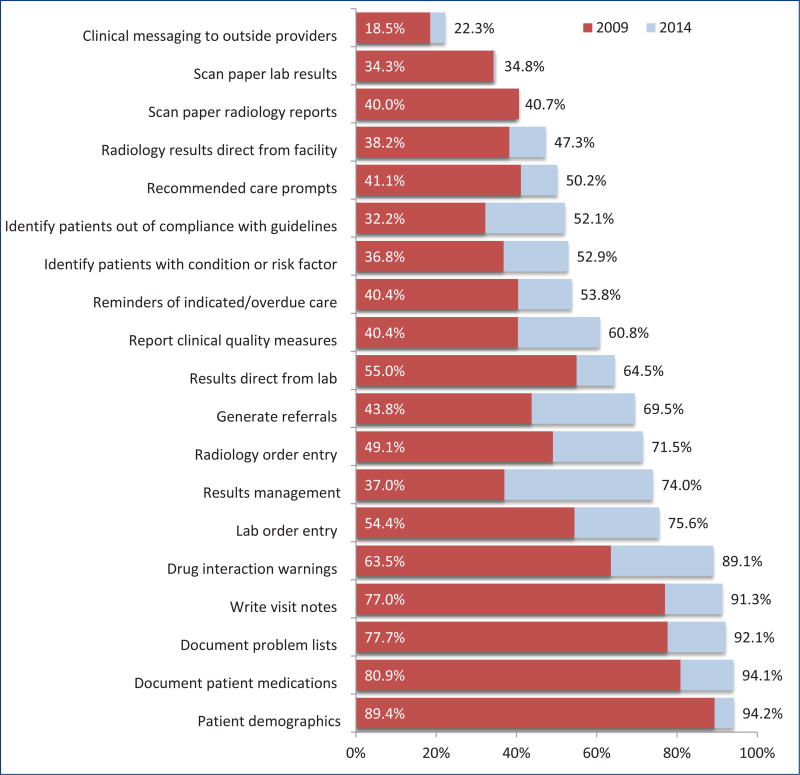

Use of EHRs increased more than threefold from 2009 to 2014 (25.1% to 89.5%), with most of the increase between 2009 and 2010 (25.1% to 72.5%). The proportion of PCPs using each functionality increased across the board, although the increase varied from a modest 0.5% for scanning results of labs to a 25.8% for generating referrals through the EHR (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Office-Based Primary Care Physicians Using EHR Functionalities “Almost Always,” 2009 and 2014

In 2014, more than half of PCPs (51.5%) reported using the prescription monitoring program with any frequency, but only one in 10 (9.8%) used it “almost always.” About a quarter of PCPs used Current-Care with any frequency (25.1%); just 3.1% reported using it “almost always.”

DISCUSSION

In this statewide analysis, we found increasing adoption and use of EHRs among PCPs over five years. PCPs’ use of EHRs to generate referrals, order tests, and report quality measures increased markedly, perhaps because EHRs make these activities easier9 and incentive programs specify quality reporting goals.10 However, quality reporting did not become commonplace. It was higher in practices with >10 vs. <5 clinicians (71% vs. 50% “almost always,” respectively). This may be due to the complexity of extracting and analyzing EHR data11 or the infrastructure and personnel needed to perform these tasks.

The 2014 data highlight other opportunities to further support PCPs’ use of many EHR functionalities, particularly those dependent on interoperability; that is, the ability of independent HIT systems to communicate and exchange data. Emerging payment models, such as accountable care organizations, will require effective cross-setting communication, particularly between PCPs and other providers.12 Yet in our analysis, fewer than one in four PCPs used secure clinical messaging, consistent with national data.13,14 Although providers may communicate in other ways, low use of EHR communication functionalities suggests the need to address barriers, e.g., interoperability15,16 and concerns regarding secure transmission of patient data.17

Our findings support previous analyses showing that younger physicians in larger practices are most likely to have EHRs and that use of some functionalities is increasing more slowly than others.18 In contrast to earlier studies,19,20 we found no evidence of a “digital divide”: RI PCPs who care for large proportions of Medicaid or uninsured patients adopted EHRs at similar rates as those who care for less vulnerable patient populations.

The state’s health information exchange, CurrentCare, and prescription monitoring program both have the potential to improve patient safety and cross-setting communication. Yet PCPs’ use of these programs is low, perhaps in part because of perceived workflow inefficiencies, such as having to switch from the EHR and login to a separate Internet-based system,21 documented in previous qualitative work.22 Incorporation of these programs into existing EHR interfaces or the use of single sign-on technology may increase uptake.23

We note several limitations to this descriptive analysis. First, physicians with EHRs may be more likely to respond to the RI HIT Survey, both because of greater interest in the topic and because they are likely to have the technical capacity. Second, responses are self-reported and thus may be subject to response bias, although this may be mitigated by the fact that the Department of Health mandates participation. Third, we classified physicians as PCPs using survey responses (for respondents) and licensure data (for non-respondents); physicians may be subject to misclassification.

In conclusion, we found accelerated adoption of EHRs in the five years since state and federal incentive programs began targeting PCPs’ adoption of HIT, but also note ongoing opportunities to support further uptake of various functionalities, particularly those that require interoperability. These findings reinforce the fact that EHR implementation does not inevitably lead to optimal use of functionalities linked to improved patient care. We call for policies that address barriers to EHR use, including core technical standards for EHRs and national certification programs to ensure EHR vendors are selling technology that can seamlessly exchange information with other health systems.24,25 Such policies, combined with research examining the barriers to EHR use, will better enable PCPs to maximize EHRs’ potential and to improve the experience of both patients and providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Healthcare Quality Reporting Program at the Rhode Island Department of Health for providing 2009–2014 Rhode Island HIT Survey data for these analyses under a data use agreement.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Brown University School of Public Health, Healthcentric Advisors, or the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Contributor Information

Sarah H. Gordon, Department of Health Services, Policy & Practice, Brown University School of Public Health..

Rosa R. Baier, Department of Health Services, Policy & Practice, Brown University School of Public Health; and Consulting Senior Scientist, Healthcentric Advisors..

Rebekah L. Gardner, Department of Medicine, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University..

References

- 1.Hillestad R, Bigelow J, Bower A, Girosi F, Meili R, Scoville R, Taylor R. Can Electronic Medical Record Systems Transform Health Care? Potential Health Benefits, Savings, and Costs. Health Affairs. 2005;24(5):1103–1117. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HITECH Act. [Accessed June 20, 2015];:112–164. http://healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf. Updated 2009.

- 3.Hsiao C, Hing E, Ashman J. Trends in electronic health record system use among office-based physicians: United States, 2007–2012. National Health Statistics Reports, no. 75. 2014 May 20;:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Health information technology in the United States: Progress and challenges ahead. [Accessed May 11, 2015]; http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2014/rwjf414891. Updated 2014.

- 5.Baier RR, Gardner RL, Buechner JS, Harris Y, Viner-Brown S, Gifford DS. Creating a survey to assess physician’s adoption of health information technology. Medical Care Research and Review. 2011:1–15. doi: 10.1177/1077558711423839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon SR, Kaushal R, et al. Physicians and electronic health records. Arch Intern Med. 2007;(167):507–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hing ES, Burt CW, Woodwell DA. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics no. 393. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. Electronic medical record use by office-based physicians and their pratices: United States, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhode Island Department of Health. Healthcare quality and reporting program. [Accessed July 16, 2015]; http://www.health.ri.gov/programs/healthcarequalityreporting/index.php. Updated 2015.

- 9.Jamoom E, Patel V, King J, Furukawa M. National perceptions of EHR adoption: Barriers, impacts, and federal policies. National Conference on Health Statistics. 2012 Aug; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality Initiatives – General Information. [Accessed August 20, 2015]; https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/qualityinitiativesgeninfo/index.html. Updated April 23 2015.

- 11.Roth CP, Lim YW, Pevnick JM, Asch SM, McGlynn EA. The challenge of measuring quality of care from the electronic health record. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2009;24:385–394. doi: 10.1177/1062860609336627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care — two essential elements of delivery-system reform. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(24):2301–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0909327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Participation has increased, but action needed to achieve goals, including improved quality of care. [Accessed August 23, 2015]; GAO-14–207, www.gao.gov/assets/670/661399.pdf. Updated Mar 6, 2014.

- 14.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Health information technology in the United States: Progress and challenges ahead. [Accessed April 2015]; http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2014/rwjf414891. Updated 2014.

- 15.Middleton B, Hammond WE, Brennan PF, Cooper GF. Accelerating U.S. EHR adoption: How to get there from here. Recommendations based on the 2004 ACMI retreat. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2005;12(1):13–19. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Connecting health and care for the nation: A shared nationwide interoperability roadmap draft version 1.0. [Accessed May 26, 2015]; http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/nationwide-interoperability-roadmap-draft-version-1.0.pdf. Updated 2015.

- 17.Dimitropoulos L, Patel V, Scheffler SA, Posnack S. Attitudes toward health information exchange: perceived benefits and concerns. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(12):111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiao C, Hing E, Ashman J. Trends in electronic health record system use among office-based physicians: United States 2007–2012. National Health Statistics Reports, no. 75. 2014 May 20;:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Shields AE, et al. Evidence of an emerging digital divide among hospitals that care for the poor. Health Affairs. 2009;28(6):1160–1170. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hing E, Burt CW. Are there patient disparities when electronic health records are adopted? Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20(2):473–488. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dullabh P, Adler-Mistein J, Hovey L, Jha AK. Final report: Key challenges to enabling health information exchange and how states can help. NORC [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhode Island Department of Health. [Accessed June 20, 2015];HIT survey physician summary report. Updated 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hope P, Zhang X. Examining user satisfaction with single sign-on and computer application roaming within emergency departments. Health Informatics Journal. 2015;21(2):107–119. doi: 10.1177/1460458213505572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. A 10-Year Vision to Achieve an Interoperable Health IT Infrastructure. [Accessed August 31, 2015]; http://healthit.gov/sites/default/files/ONC10yearInteroperabilityConceptPaper.pdf. Updated June 5, 2014.

- 25.The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. [Accessed August 31, 2015];Report to Congress. http://healthit.gov/sites/default/files/reports/info_blocking_040915.pdf. Updated April 2015.