Abstract

Background

The elderly are predisposed to septic arthritis (SA) because of the aging nature and increasing comorbidities. SA may in turn increase the long-term mortality in the geriatric patients; however, it remains unclear. We conducted this prospective nationwide population-based cohort study to clarify this issue.

Methods

Using Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), we identified 1667 geriatric participants (≥ 65 years) with SA and 16,670 geriatric participants without SA matched at a ratio of 1:10 by age, sex, and index date between 1999 and 2010. A comparison of the long-term mortality between the two cohorts through follow-up until 2011 was performed.

Results

Geriatric participants with SA had a significantly increased mortality than those without SA [Adjusted hazard ratio (AHR): 1.49, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.34–1.66], particularly the old elderly (≥ 85 years, AHR: 2.12, 95% CI: 1.58–2.84) and males (AHR: 1.54, 95% CI: 1.33–1.79). These results were stated after adjustment for osteoarthritis, diabetes, gout, renal disease, liver disease, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, alcoholism, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. The increased mortality risk was highest in the first month (AHR: 3.93, 95% CI: 2.94–5.25) and remained increased even after following up for 2–4 years (AHR: 1.30, 95% CI: 1.03–1.65). After Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, SA (AHR: 1.37, 95% CI: 1.20–1.56), older age (≥ 85 years, AHR: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.59–2.02, 75–84 years, AHR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.53–1.78), male sex, diabetes, renal disease, liver disease, cancer, and gout were independent mortality predictors. There was no significant difference in the mortality for SA between upper limb affected and lower limb affected.

Conclusions

This study delineated that SA significantly increased the long-term mortality in geriatric participants. For the increasing aging population worldwide, strategies for the prevention and treatment of SA and concomitant control of comorbidities are very important.

Keywords: Elderly, Geriatric, Mortality, Septic arthritis

Background

Aging issues are very important because the elderly (≥ 65 years old) are expected to increase rapidly from 6.2% of the world population in 1992 to 20% by 2050 [1]. In Taiwan, the geriatric population increased from 7% in 1993 to 12.5% in 2015 [2] and is expected to grow to 20% in 2025 [3]; Taiwan is one of the most rapidly aging countries in the world. The increasing geriatric population needs more medical healthcare resources, which reached 33.5% expenditure of Taiwan National Health Insurance in 2011; this percentage still rises [3].

Septic arthritis (SA) is a common joint infection [4] and is often caused by bacteria, viruses, or other less-common pathogens [4]. SA usually involves single and large joints, such as the knee joint, but many others may be involved [4]. In the United States, the incidence rate of SA is 0.01% in the general population annually; however, it increases to 0.07% in the high-risk groups such as those with rheumatoid arthritis or a prosthetic joint [5]. The predisposing factors for SA are as follows: (1) age > 80 years; (2) weak immune system due to diabetes, renal, and liver diseases, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and use of immune-suppression drugs; (3) alcohol abuse; (4) cancer; (5) rheumatoid arthritis; (6) presence of prosthetic joint; (7) recent joint surgery; (8) skin infection; and (9) prior intra-articular corticosteroid injection [4–6].

Geriatric population is more vulnerable to SA because they have more risk factors than the younger population. The mortality for SA in geriatric patients is also higher than that in younger population due to delayed diagnosis and treatment, underlying comorbidities, and decreased physiological reserve [7]. Previous studies about geriatric SA are rare and focused on the identifications of the risk factors or treatments [8, 9]; however, the long-term mortality and mortality predictors after SA have never been clarified. Therefore, we conducted this nationwide population-based cohort based on Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) to determine the risk for long-term mortality in geriatric patients with SA as well as the mortality predictors.

Methods

Data sources

Taiwan launched a National Health Insurance program including almost all Taiwan’s citizens since March 1st, 1995 [10]. Large computerized databases containing the data of registration and claim diagnosis for reimbursement are derived from this system through the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan and are maintained by the National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan; the databases are provided to scientists in Taiwan for research [10]. This study was based on the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 (LHID2000), which contains the entire original claim data of 1,000,000 beneficiaries enrolled in year 2000, randomly selected from the original NHIRD [10].

Study design, participants, and definitions of the variables

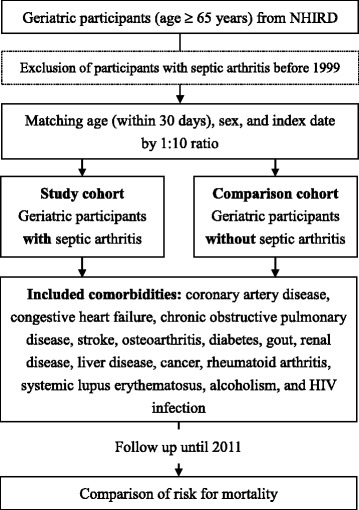

Using LHID2000, we conducted a prospective nationwide population-based cohort study. We first identified all geriatric participants (age ≥ 65 years) and excluded those who had SA (ICD-9 code: 711.0) before 1999 (Fig. 1). We excluded participants with SA before 1999 to include new-onset SA only because this method could help us use the index date (i.e., the date of diagnosis for SA in the geriatric participants with SA) to match the comparison cohort and Cox proportional hazard regression to compare the risk for mortality. Next, we matched geriatric participants with and without SA between the period of January 1st, 1999 and December 31, 2010. These subjects were selected as the study cohort and the comparison cohort, respectively, matched at a ratio of 1:10 by age, sex, and index date. For stratified analysis, we categorized geriatric participants into three age subgroups: young elderly (65–74 years), moderately elderly (75–84 years), and old elderly (≥ 85 years), which is the most common criteria in the literatures [11, 12]. The underlying comorbidities that affect mortality included in this study were defined as follows: coronary artery disease (ICD-9 codes 410–414), congestive heart failure (ICD-9 code 428), chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (ICD-9 code 496), stroke (ICD-9 codes 436–438), osteoarthritis (ICD-9 code 715), diabetes (ICD-9 code 250), gout (ICD-9 code 274), renal disease (ICD-9 codes 582, 583, 585, 586, and 588), liver disease (ICD-9 codes 570–573), cancer (ICD-9 codes 140–208), rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-9 code 714), systemic lupus erythematosus (ICD-9 code 710.0), alcoholism (ICD-9 codes 291, 303), and HIV infection (ICD-9 codes 042–044). We also classified the affected areas as upper limbs (ICD-9 codes 711.01–711.04) and lower limbs (ICD-9 codes 711.05–711.07). Unspecified and multiple sites were excluded from the analysis concerning differences among affected sites due to the difficulty of classification. We followed up the participants until the end of 2011 to compare the all-cause mortality risk between both cohorts. According to the law in Taiwan, all citizens or people owning a residence permit are mandatory to participate in the National Health Insurance, and they must be dropped out of the National Health Insurance within 30 days after death. Therefore, we defined the death as the participant had the diagnosis of death or withdrew from the National Health Insurance. Stratified analyses by age subgroups and sex were performed to evaluate the effect modification of age and sex.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study. NHIRD, National Health Insurance Research Database

Ethic statements

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Chi-Mei Medical Center and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Because the LHID2000 used in this study consists of unidentifiable and secondary data released to the public for research, informed consent was waived. The waiver does not affect the rights and welfare of the participants.

Statistical analysis

SAS 9.3.1 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. In the comparison of age, sex, and underlying comorbidities between the two cohorts, we used Pearson chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent t test for continuous variables. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with adjustment for coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, osteoarthritis, diabetes, gout, renal disease, liver disease, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and alcoholism was used to compare the mortality risk between the two cohorts. Kaplan-Meier curve and log-rank test for comparing mortality between participants with and without SA was also performed. Finally, we investigated the independent mortality predictor by Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. Significance level was set at 0.05 (two-tailed). Due to the simple covariate adjustment within Cox models may not fully adjust for such imbalance, and unmeasured confounder may exist [13]. Thus, we also conducted additional sensitivity analysis for the unmeasured confounder to strengthen the article base on the proposed method of Lin et al. (Appendix: Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis for the residual confounding effects of unmeasured variable after adjusting for measured covariates

| P0 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 0 | 1.23 | 1.353 | 1.476 | 1.599 | 1.722 | 1.845 |

| (1.080,1.400) | (1.188,1.540) | (1.296,1.680) | (1.404,1.820) | (1.512,1.960) | (1.620,2.100) | ||

| 0.2 | 1.025 | 1.127 | 1.23 | 1.333 | 1.435 | 1.537 | |

| (0.900,1.167) | (0.990,1.283) | (1.080,1.400) | (1.170,1.517) | (1.260,1.633) | (1.350,1.750) | ||

| 0.4 | 0.879 | 0.966 | 1.054 | 1.142 | 1.23 | 1.318 | |

| (0.771,1.000) | (0.849,1.100) | (0.926,1.200) | (1.003,1.300) | (1.080,1.400) | (1.157,1.500) | ||

| 0.6 | 0.769 | 0.846 | 0.922 | 0.999 | 1.076 | 1.153 | |

| (0.675,0.875) | (0.743,0.962) | (0.810,1.050) | (0.878,1.137) | (0.945,1.225) | (1.013,1.312) | ||

| 0.8 | 0.683 | 0.752 | 0.82 | 0.888 | 0.957 | 1.025 | |

| (0.600,0.778) | (0.660,0.856) | (0.720,0.933) | (0.780,1.011) | (0.840,1.089) | (0.900,1.167) | ||

| 1 | 0.615 | 0.676 | 0.738 | 0.8 | 0.861 | 0.922 | |

| (0.540,0.700) | (0.594,0.770) | (0.648,0.840) | (0.702,0.910) | (0.756,0.980) | (0.810,1.050) | ||

| 6 | 0 | 1.23 | 1.845 | 2.46 | 3.075 | 3.69 | 4.305 |

| (1.080,1.400) | (1.620,2.100) | (2.160,2.800) | (2.700,3.500) | (3.240,4.200) | (3.780,4.900) | ||

| 0.2 | 0.615 | 0.922 | 1.23 | 1.537 | 1.845 | 2.153 | |

| (0.540,0.700) | (0.810,1.050) | (1.080,1.400) | (1.350,1.750) | (1.620,2.100) | (1.890,2.450) | ||

| 0.4 | 0.41 | 0.615 | 0.82 | 1.025 | 1.23 | 1.435 | |

| (0.360,0.467) | (0.540,0.700) | (0.720,0.933) | (0.900,1.167) | (1.080,1.400) | (1.260,1.633) | ||

| 0.6 | 0.307 | 0.461 | 0.615 | 0.769 | 0.923 | 1.076 | |

| (0.270,0.350) | (0.405,0.525) | (0.540,0.700) | (0.675,0.875) | (0.810,1.050) | (0.945,1.225) | ||

| 0.8 | 0.246 | 0.369 | 0.492 | 0.615 | 0.738 | 0.861 | |

| (0.216,0.280) | (0.324,0.420) | (0.432,0.560) | (0.540,0.700) | (0.648,0.840) | (0.756,0.980) | ||

| 1 | 0.205 | 0.307 | 0.41 | 0.513 | 0.615 | 0.718 | |

| (0.180,0.233) | (0.270,0.350) | (0.360,0.467) | (0.450,0.583) | (0.540,0.700) | (0.630,0.817) | ||

| 10 | 0 | 1.23 | 2.337 | 3.444 | 4.551 | 5.658 | 6.765 |

| (1.080,1.400) | (2.052,2.660) | (3.024,3.920) | (3.996,5.180) | (4.968,6.440) | (5.940,7.700) | ||

| 0.2 | 0.439 | 0.835 | 1.23 | 1.625 | 2.021 | 2.416 | |

| (0.386,0.500) | (0.733,0.950) | (1.080,1.400) | (1.427,1.850) | (1.774,2.300) | (2.121,2.750) | ||

| 0.4 | 0.267 | 0.508 | 0.749 | 0.989 | 1.23 | 1.471 | |

| (0.235,0.304) | (0.446,0.578) | (0.657,0.852) | (0.869,1.126) | (1.080,1.400) | (1.291,1.674) | ||

| 0.6 | 0.192 | 0.365 | 0.538 | 0.711 | 0.884 | 1.057 | |

| (0.169,0.219) | (0.321,0.416) | (0.472,0.612) | (0.624,0.809) | (0.776,1.006) | (0.928,1.203) | ||

| 0.8 | 0.15 | 0.285 | 0.42 | 0.555 | 0.69 | 0.825 | |

| (0.132,0.171) | (0.250,0.324) | (0.369,0.478) | (0.487,0.632) | (0.606,0.785) | (0.724,0.939) | ||

| 1 | 0.123 | 0.234 | 0.344 | 0.455 | 0.566 | 0.676 | |

| (0.108,0.140) | (0.205,0.266) | (0.302,0.392) | (0.400,0.518) | (0.497,0.644) | (0.594,0.770) | ||

Results

The mean age in both cohorts was 74.6 years and the majority of geriatric participants were within the subgroup age 65–74 years (approximately 53%) (Table 1). The sex ratio was nearly equal in both cohorts. The common underlying comorbidities in the geriatric participants with SA were coronary artery disease (20.6%), congestive heart failure (8.4%), chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (17.3%), stroke (14.8%), osteoarthritis (32.3%), diabetes (28.6%), gout (17.4%), renal disease (9.9%), liver disease (9.5%), cancer (6.2%), rheumatoid arthritis (2.2%), and alcoholism (0.1%). There was no HIV infection in the participants. In the comparison of underlying comorbidities, geriatric participants with SA had significantly higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, stroke, osteoarthritis, diabetes, gout, renal disease, liver disease, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus than those without SA (all p-value <0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for geriatric participants with and without SA

| Variable | With SA (n = 1667) |

Without SA (n = 16,670) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 74.6 ± 6.7 | 74.6 ± 6.6 | 0.764 |

| Age (years) | 0.945 | ||

| 65–74 | 893 (53.6) | 8964 (53.8) | |

| 75–84 | 619 (37.1) | 6197 (37.2) | |

| ≥85 | 155 (9.3) | 1509 (9.1) | |

| Sex | >0.999 | ||

| Female | 843 (50.6) | 8430 (50.6) | |

| Male | 824 (49.4) | 8240 (49.4) | |

| Underlying comorbidity | |||

| Coronary artery disease | 343 (20.6) | 2065 (12.4) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 140 (8.4) | 478 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary obstructive disease | 288 (17.3) | 1640 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 247 (14.8) | 1484 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| Osteoarthritis | 539 (32.3) | 1753 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 477 (28.6) | 2828 (17.0) | <0.001 |

| Gout | 290 (17.4) | 752 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 165 (9.9) | 482 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 158 (9.5) | 717 (4.3) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 103 (6.2) | 680 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 36 (2.2) | 60 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 9 (0.5) | 8 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Alcoholism | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.04) | 0.534 |

| HIV infection | 0 | 0 | - |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or n (%)

SA septic arthritis, HIV human immunodeficiency virus

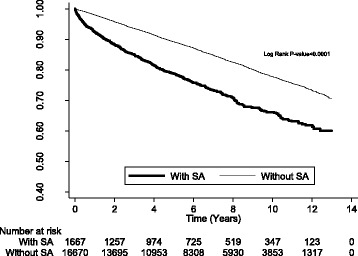

Geriatric participants with SA had a significantly higher mortality risk than those without SA [adjusted hazard ratio (AHR): 1.39, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.25–1.55] (Table 2). Older geriatric participants had higher mortality risk than the younger (AHRs in 65–74, 75–84, and ≥ 85 years old were 1.26, 1.44, and 1.86, respectively). Stratified analysis by sex showed there was a higher mortality risk in the male population than in female population. In the stratified analysis by the follow-up period, geriatric participants with SA had the highest mortality risk as compared with those without SA in the first 6 months after diagnosis (AHR: 3.38, 95% CI: 2.52–4.54). The impact of SA on mortality lasted until 1–2 years (AHR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.11–1.98). Kaplan-Meier curve and log-rank test also showed that participants with SA had a lower survival than participants without SA during the follow-up (p-value < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of mortality risk between geriatric participants with and without SA using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis

| Variable | With SA | Without SA | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Number of death | PY | Rate | n | Number of death | PY | Rate | |||

| All | 1667 | 430 | 9437.16 | 455.65 | 16,670 | 2545 | 104,188.3 | 244.27 | 1.87 (1.69–2.07) | 1.39 (1.25–1.55) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 65–74 | 893 | 167 | 5612.95 | 297.53 | 8964 | 1075 | 60,096.6 | 178.88 | 1.67 (1.42–1.96) | 1.26 (1.06–1.50) |

| 75–84 | 619 | 196 | 3215.66 | 609.52 | 6197 | 1206 | 36,364.3 | 331.64 | 1.85 (1.59–2.15) | 1.44 (1.23–1.68) |

| ≥ 85 | 155 | 67 | 608.55 | 1100.98 | 1509 | 264 | 7727.47 | 341.64 | 3.15 (2.41–4.12) | 1.86 (1.39–2.51) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 843 | 191 | 5069.5 | 376.76 | 8430 | 1184 | 53,837.31 | 219.92 | 1.71 (1.47–2.00) | 1.33 (1.13–1.56) |

| Male | 824 | 239 | 4367.66 | 547.2 | 8240 | 1361 | 50,350.98 | 270.30 | 2.03 (1.77–2.32) | 1.47 (1.27–1.70) |

| Follow-up period | ||||||||||

| 1–6 months | 1667 | 86 | 795.7 | 1080.81 | 16,670 | 152 | 8166.58 | 186.12 | 5.73 (4.39–7.47) | 3.38 (2.52–4.54) |

| 6–12 months | 1530 | 39 | 740.5 | 526.67 | 16,010 | 171 | 7807.51 | 219.02 | 2.40 (1.70–3.40) | 1.61 (1.10–2.35) |

| 1–2 years | 1427 | 62 | 1344.36 | 461.19 | 15,185 | 332 | 14,472.93 | 229.39 | 2.01 (1.53–2.64) | 1.49 (1.11–1.98) |

| 2–4 years | 1257 | 88 | 2225.73 | 395.38 | 13,695 | 571 | 24,604.46 | 232.07 | 1.70 (1.36–2.13) | 1.20 (0.94–1.51) |

| 4–6 years | 974 | 61 | 1694.27 | 360.04 | 10,953 | 461 | 19,194.34 | 240.18 | 1.50 (1.15–1.96) | 1.18 (0.90–1.56) |

| > 6 years | 725 | 94 | 2636.6 | 356.52 | 8308 | 858 | 29,942.47 | 286.55 | 1.24 (1.01–1.54) | 1.07 (0.86–1.34) |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or n (%)

SA septic arthritis, AHR adjusted hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, PY person-year

aAdjusted by coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, osteoarthritis, diabetes, gout, renal disease, liver disease, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and alcoholism

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve and log-rank test between participants with SA and without SA (outcome = mortality)

After Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, we found that SA (AHR: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.08–1.40), older age (≥ 85 and 75–84: AHR 2.18, 95% CI 1.93–2.47, and AHR 1.82, 95% CI 1.68–1.97, respectively), male sex (AHR: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.15–1.33), underlying comorbidities of congestive heart failure (AHR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.10–1.51), chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (AHR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.35–1.65), stroke (AHR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.50–1.84), diabetes (AHR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.55–1.83), gout (AHR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.10–1.43), renal disease (AHR: 2.29, 95% CI: 2.00–2.62), liver disease (AHR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.32–1.73), cancer (AHR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.51–2.01), and rheumatoid arthritis (AHR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.02–2.34) were independent mortality predictors (Table 3). Participants with SA affected in lower limbs had a lower mortality than in upper limbs.

Table 3.

Independent predictors for mortality in the total participants using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis

| Variable | Crude HR (95% CI) | AHR (95% CI)* | p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | |||

| With SA | 1.87 (1.69–2.07) | 1.23 (1.08–1.40) | 0.002 |

| Without SA | 1 | 1 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 65–74 | 1 | 1 | |

| 75–84 | 1.90 (1.76–2.05) | 1.82 (1.68–1.97) | <0.001 |

| ≥ 85 | 2.14 (1.89–2.41) | 2.18 (1.93–2.47) | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1 | 1 | |

| Male | 1.26 (1.17–1.35) | 1.23 (1.15–1.33) | <0.001 |

| Underlying comorbidity | |||

| Coronary artery disease | 1.48 (1.35–1.63) | 1.10 (0.99–1.21) | 0.069 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2.54 (2.20–2.94) | 1.29 (1.10–1.51) | 0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary obstructive disease | 2.09 (1.90–2.29) | 1.49 (1.35–1.65) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 2.21 (2.01–2.44) | 1.66 (1.50–1.84) | <0.001 |

| Osteoarthritis | 1.07 (0.97–1.19) | 0.99 (0.89–1.11) | 0.929 |

| Diabetes | 1.94 (1.79–2.10) | 1.69 (1.55–1.83) | <0.001 |

| Gout | 1.62 (1.42–1.84) | 1.25 (1.10–1.43) | 0.001 |

| Renal disease | 3.76 (3.31–4.27) | 2.29 (2.00–2.62) | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 1.85 (1.62–2.11) | 1.51 (1.32–1.73) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 1.90 (1.65–2.18) | 1.74 (1.51–2.01) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.86 (1.23–2.80) | 1.55 (1.02–2.34) | 0.039 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 0.96 (0.31–2.99) | 0.62 (0.20–1.93) | 0.411 |

| Alcoholism | 0.74 (0.10–5.24) | 0.81 (0.11–5.73) | 0.829 |

| Affected area | |||

| Upper limbs (n = 109) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Lower limbs (n = 585) | 0.88 (0.62–1.25) | 0.69 (0.57–0.84) | <0.001 |

SA septic arthritis, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, PY person-year

*Adjusted by coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, osteoarthritis, diabetes, gout, renal disease, liver disease, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and alcoholism

†For AHR

Discussion

This prospective nationwide population-based cohort study revealed that geriatric participants with SA had a significantly higher mortality risk than those without SA. The common underlying comorbidities in geriatric participants with SA were osteoarthritis, diabetes, coronary artery disease, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, gout, stroke, renal disease, liver disease, congestive heart failure, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis. SA impacted the mortality risk more markedly in the first 6 months after the diagnosis and its effect lasted until 1–2 years. The mortality in older geriatric participants was affected by SA more frequently than that in younger geriatric participants. Male sex, older age, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, stroke, diabetes, gout, renal disease, liver disease, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis were also independent mortality predictors.

Advancing age is itself a risk factor and a mortality predictor for SA [14]. A single hospital-based study for SA reported that 61.4% of patients were >60 years and 12.5% of patients were ≥80 years [14]. The hospital mortality rate increased with age: 0.7% of patients <60 years, 4.8% of those 60–79 years, and 9.5% of those ≥80 years [14]. Another study reported that despite surgical treatment in the geriatric patients with SA, the complications were still high: 38% had osteomyelitis, 14% had secondary osteoarthritis, and 19% showed mortality due to sepsis [15]. In addition to the decreased immunity and increased comorbidities in the geriatric patients, the other explanation was that the diagnosis of infection in the elderly is more difficult due to the atypical manifestations [7]. Positive outcome needs an early diagnosis and treatment [7, 15]. The explanation for increased long-term mortality in geriatric participants with SA is multi-factorial. One of them is the dysfunction of the joint despite proper treatment, which results in subsequent disability of daily activity [16]. A study reported that severe activity of daily life (ADL) limitations and receiving ADL assistance significantly increased the subsequent mortality [odds ratio (OR): 19.75, 95% CI 9.81–39.76 and OR: 16.57, 95% CI 8.39–32.73, respectively] [17]. Another study reported that the disability for at least one ADL item predicted in-hospital death in the admitted geriatric patients (OR: 2.16, 95% CI: 1.55–2.99) [18]. A population-based study in the Netherlands reported that there was an increased mortality risk in the disabled population than in the non-disabled population [19]. Severe disability may has an independent effect for mortality despite that the risk factors preceding the disability could explain the difference in mild disability [19].

Inflammation after SA or its complications is also a possible mechanism for increasing the mortality [20]. A study about acute-care hospitalized elderly patients reported that C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 30 mg/l predicted mortality (OR: 3.72, 95% CI: 1.34–10.31) [18]. SA may result in subsequent osteomyelitis [15] or chronic SA, which may cause a chronic inflammation and increase long-term mortality [21]. A nationwide population-based cohort study reported that geriatric participants with chronic osteomyelitis had a significantly higher mortality risk than those without chronic osteomyelitis [incidence rate ratio (IRR): 2.29, 95% CI: 2.01–2.59] [21]. The mortality risk was highest in the first month (IRR: 5.01, 95% CI: 2.02–12.42) and still higher even after 6 years (IRR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.13–2.06) of follow-up [21]. This study did not analyze the cause of chronic osteomyelitis; however, it did provide us an insight into the effect of chronic osteomyelitis, a common complication after SA. In addition to ADL limitations and inflammation, the possible explanations for highest mortality risk in the first 6 months after the diagnosis are disseminated infection, acute renal failure, and cardiopulmonary failure [22].

We showed that joints of the lower limbs were more affected than those of the upper limbs (n = 585 vs. n = 109), which was consistent with previous studies that showed that large joints in the lower limbs, such as knee and hip, were more commonly involved than small joints [14–16, 22]. The present study showed that SA in the lower limbs had a lower mortality than in upper limbs. However, a previous study reported that SA involving the hip or shoulder predicted poor outcome [23], which suggests that the comparison of outcome between the upper or lower limbs warrants more study in the future.

We showed that male sex, older age, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, stroke, diabetes, gout, renal disease, liver disease, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis also predicted mortality; however, systemic lupus erythematosus, a risk factor for SA [24], did not predict mortality. It suggests that we should treat SA as well as control other comorbidities simultaneously to decrease the subsequent mortality.

The strength of this study was that it clarified the long-term mortality and independent mortality predictors in geriatric participants with SA, which remained unclear. Despite its strength, this study had some limitations. First, the NHIRD contains no information on the severity of SA, some important laboratory data such as pathogens of blood culture or synovial fluid, and participants’ social economic status and post-diagnosis health care conditions (e.g., received good or bad quality health care? stay at home or in hospital or in nursing home?); therefore, we were unable to evaluate the severity association between them. Studies with more detail information are needed for the causal relationship between mortality and SA. Second, we did not identify the drug use, definite infected joints, and the relationship with previous surgery or prosthesis. Third, categorization of age is more convenient for clinical use; however, it may loss some information. Fourth, although our study was a nationwide population-based study, the result may not be applied to other nations due to the differences in race, culture, and environment.

Conclusions

This prospective nationwide population-based cohort study showed that long-term mortality was significantly higher in geriatric participants with SA than in those without SA. The influence was highest in the first 6 months after diagnosis and lasted until 1–2 years. The impact of SA on mortality was more pronounced in the older geriatric participants than in the younger geriatric participants. In addition to SA, male sex, older age, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, stroke, diabetes, gout, renal disease, liver disease, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis were independent mortality predictors. For the increasing aging population worldwide, strategies for the prevention and treatment of SA and concomitant control of comorbidities are very important.

Acknowledgments

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health and managed by National Health Research Institutes. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of National Health Insurance Administration, Department of Health or National Health Research Institutes.

Funding

This study was supported by grants CMFHR10594 from the Chi-Mei Medical Center.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) published by Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) Bureau. Due to legal restrictions imposed by the government of Taiwan in relation to the “Personal Information Protection Act”, data cannot be made publicly available. Requests for data can be sent as a formal proposal to the NHIRD (http://nhird.nhri.org.tw).

Abbreviations

- ADL

activity of daily life

- AHR

adjusted hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IRR

incidence rate ratio

- LHID

Longitudinal Health Insurance Database

- NHIRD

National Health Insurance Research Database

- OR

odds ratio

- SA

septic arthritis

Appendix

Authors’ contributions

CJW, CC Huang, and HJL designed the study and wrote the manuscript. SFW performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. PJC, CC Hsu, JJW, and HRG provided their clinical experience and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Chi-Mei Medical Center and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Because the LHID2000 used in this study consists of unidentifiable and secondary data released to the public for research, informed consent was waived. The waiver does not affect the rights and welfare of the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chia-Jung Wu, Email: ffbarry2521@gmail.com.

Chien-Cheng Huang, Email: chienchenghuang@yahoo.com.tw.

Shih-Feng Weng, Email: also99@gmail.com.

Ping-Jen Chen, Email: pingjen.chen@gmail.com.

Chien-Chin Hsu, Email: nych2525@gmail.com.

Jhi-Joung Wang, Email: 400002@mail.chimei.org.tw.

How-Ran Guo, Email: hrguo@mail.ncku.edu.tw.

Hung-Jung Lin, Phone: +886-6-281-2811, Email: hjlin52@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Cagatay AA, Tufan F, Hindilerden F, et al. The causes of acute fever requiring hospitalization in geriatric patients: comparison of infectious and noninfectious etiology. J Aging Res. 2010;2010:380892. doi: 10.4061/2010/380892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Statistics, Ministry of Interior, Taiwan. Analysis of the population structure. Accessed from http://www.moi.gov.tw/stat/news_content.aspx?sn=10225&page=0 on February 28, 2016.

- 3.National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. The impact of aging on the medical expenditure. Accessed from http://www.nhi.gov.tw/epaperN/ItemDetail.aspx?DataID=3431&IsWebData=0&ItemTypeID=5&PapersID=299&PicID= on February 28, 2016.

- 4.Zeller JL, Lynm C, Glass RM. Septic arthritis. JAMA. 2007;297:1510. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaandorp CJ, van Schaardenburg D, Krijnen P, Habbema JD, van De Laar MA. Risk factors for septic arthritis in patients with joint disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1819–1825. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathews CJ, Coakley G. Septic arthritis: current diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:457. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283036975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norman DC, Yoshikawa TT. Fever in the elderly. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1996;10:93–99. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGuire NM, Kauffman CA. Septic arthritis in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33:170–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb04887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaandorp CJ, Krijnen P, Moens HJ, Habbema JD, van Schaardenburg D. The outcome of bacterial arthritis: a prospective community-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:884–892. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health Insurance Research Database. Accessed from http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/Data_Subsets.html on March 28, 2016.

- 11.Huang CC, Weng SF, Tsai KT, Chen PJ, Lin HJ, Wang JJ, Su SB, Chou W, Guo HR, Hsu CC. Long-term mortality risk after hyperglycemic crisis episodes in geriatric patients with diabetes: a national population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:746–751. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung MH, Huang CC, Vong SC, Yang TM, Chen KT, Lin HJ, Chen JH, Su SB, Guo HR, Hsu CC. Geriatric fever score: a new decision rule for geriatric care. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin DY, Psaty BM, Kronmal RA. Assessing the sensitivity of regression results to unmeasured confounders in observational studies. Biometrics. 1998;54:948–963. doi: 10.2307/2533848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gavet F, Tournadre A, Soubrier M, Ristori JM, Dubost JJ. Septic arthritis in patients aged 80 and older: a comparison with younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1210–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent GM, Amirault JD. Septic arthritis in the elderly. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;251:241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weston VC, Jones AC, Bradbury N, Fawthrop F, Doherty M. Clinical features and outcome of septic arthritis in a single UK Health District 1982-1991. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:214–219. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.4.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrade FC, Guevara PE, Lebrão ML, Duarte YA. Correlates of the incidence of disability and mortality among older adult Brazilians with and without diabetes mellitus and stroke. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:361. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forasassi C, Golmard JL, Pautas E, Piette F, Myara I, Raynaud-Simon A. Inflammation and disability as risk factors for mortality in elderly acute care patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48:406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majer IM, Nusselder WJ, Mackenbach JP, Klijs B, van Baal PH. Mortality risk associated with disability: a population-based record linkage study. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:e9–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Martinis M, Franceschi C, Monti D, Ginaldi L. Inflammation markers predicting frailty and mortality in the elderly. Exp Mol Pathol. 2006;80:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang CC, Tsai KT, Weng SF, Lin HJ, Huang HS, Wang JJ, Guo HR, Hsu CC. Chronic osteomyelitis increases long-term mortality risk in the elderly: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:72. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0248-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molloy A, Laing A, O’Shea K, Bell L, O’Rourke K. The complications of septic arthritis in the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2010;22:270–273. doi: 10.1007/BF03324807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldenberg DL, Cohen AS. Acute infectious arthritis. A review of patients with nongonococcal joint infections (with emphasis on therapy and prognosis) Am J Med. 1976;60:369–377. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90753-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathews CJ, Kingsley G, Field M, Jones A, Weston VC, Phillips M, Walker D, Coakley G. Management of septic arthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:440–445. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.058909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) published by Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) Bureau. Due to legal restrictions imposed by the government of Taiwan in relation to the “Personal Information Protection Act”, data cannot be made publicly available. Requests for data can be sent as a formal proposal to the NHIRD (http://nhird.nhri.org.tw).