Abstract

Background

Among the 13 families of early-diverging eudicots, only Circaeasteraceae (Ranunculales), which consists of the two monotypic genera Circaeaster and Kingdonia, lacks a published complete plastome sequence. In addition, the phylogenetic position of Circaeasteraceae as sister to Lardizabalaceae has only been weakly or moderately supported in previous studies using smaller data sets. Moreover, previous plastome studies have documented a number of novel structural rearrangements among early-divergent eudicots. Hence it is important to sequence plastomes from Circaeasteraceae to better understand plastome evolution in early-diverging eudicots and to further investigate the phylogenetic position of Circaeasteraceae.

Results

Using an Illumina HiSeq 2000, complete plastomes were sequenced from both living members of Circaeasteraceae: Circaeaster agrestis and Kingdonia uniflora. Plastome structure and gene content were compared between these two plastomes, and with those of other early-diverging eudicot plastomes. Phylogenetic analysis of a 79-gene, 99-taxon data set including exemplars of all families of early-diverging eudicots was conducted to resolve the phylogenetic position of Circaeasteraceae.

Both plastomes possess the typical quadripartite structure of land plant plastomes. However, a large ~49 kb inversion and a small ~3.5 kb inversion were found in the large single-copy regions of both plastomes, while Circaeaster possesses a number of other rearrangements, particularly in the Inverted Repeat. In addition, infA was found to be a pseudogene and accD was found to be absent within Circaeaster, whereas all ndh genes, except for ndhE and ndhJ, were found to be either pseudogenized (ΨndhA, ΨndhB, ΨndhD, ΨndhH and ΨndhK) or absent (ndhC, ndhF, ndhI and ndhG) in Kingdonia. Circaeasteraceae was strongly supported as sister to Lardizabalaceae in phylogenetic analyses.

Conclusion

The first plastome sequencing of Circaeasteraceae resulted in the discovery of several unusual rearrangements and the loss of ndh genes, and confirms the sister relationship between Circaeasteraceae and Lardizabalaceae. This research provides new insight to characterize plastome structural evolution in early-diverging eudicots and to better understand relationships within Ranunculales.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3956-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Early-diverging eudicots, Circaeasteraceae, Plastome, Rearrangements, Gene loss, Phylogenetic analyses

Background

The early-diverging eudicot family Circaeasteraceae (Ranunculales) sensu APG IV [1] contains only the two monotypic genera Circaeaster Maxim. and Kingdonia Balf.f. & W.W. Smith, which were historically treated as separate families (Circaeasteraceae and Kingdoniaceae) (e.g. [2–6]). Kingdonia has also been placed in Ranunculaceae in the past (e.g. [7–10]). Circaeaster agrestis Maxim. can be found in China and the Himalayas, whereas Kingdonia uniflora Balf.f. & W.W. Smith is endemic to China. Fossil fruits somewhat similar to those of Circaeaster have been reported from the mid-Albian of Virginia, USA [11, 12], while no fossil record is known for Kingdonia. Both species are herbs growing at high elevations, and possess the same distinctive dichotomous venation, which is very rare among angiosperms.

The Ranunculales sensu APG IV [1] form a well-supported clade comprised of seven families: Berberidaceae, Circaeasteraceae, Eupteleaceae, Lardizabalaceae, Menispermaceae, Papaveraceae and Ranunculaceae. To date, complete plastomes have been sequenced for representatives from all of these families except Circaeasteraceae [13–24]. These and plastomes from other eudicot families have helped to successfully resolve phylogenetic relationships among early-diverging eudicots, including among most families of Ranunculales (e.g.[17–19, 23, 24]). This is highly promising given that the relationships among many of these families had been poorly to moderately resolved in previous studies utilizing only a few genes (e.g. [25–38]). In previous phylogenetic studies of Ranunculales based on only a few genes, Circaeasteraceae has been resolved as sister to Lardizabalaceae, but only with weak or moderate support [25, 26, 29, 32, 36, 38, 39].

Over the past decade, knowledge of the organization and evolution of angiosperm plastomes has rapidly expanded [40, 41]. Plastomes of most flowering plants possess a typical quadripartite structure with two Inverted Repeat regions (IRA and IRB) separating the Small and Large Single-Copy regions (SSC and LSC) [42]. Nevertheless, deviations from this canonical structure have been found with increasing frequency as the pace of plastome sequencing has exploded in recent years. For example, the length of the IR region has been found to vary significantly in some plant groups (e.g. [43–45]), and Sun et al. [23] documented six major “IR types” among 18 early-diverging eudicot plastomes, representing 12 of the 13 early-diverging eudicot families. Reconstruction of the ancestral IR gene content suggests that 18 genes were likely present in the IR region of the ancestor of eudicots [23], although representatives from Circaeasteraceae were absent from this study. Likewise, large inversions have been detected throughout the plastome in an increasing number of taxa (e.g. [46–50]). However, no obvious large inversions or rearrangements have been detected from early-diverging eudicot plastomes. Finally, gene loss (including pseudogenization) has also been found to be widespread among angiosperm plastomes, especially in species whose plastomes are highly rearranged [51].

To characterize plastome structural evolution in early-diverging eudicots and to better understand relationships within Ranunculales, we sequenced the complete plastomes of both extant species of Circaeasteraceae and included these two plastomes in a larger phylogenetic analysis including representatives of all major lineages of angiosperms. Consistent with previous work, we find that these complete plastome sequences improve support for phylogenetic relationships among Ranunculales, including the position of Circaeasteraceae. Moreover, we report several significant plastome structural changes, including a large inversion and several gene loss events.

Results

Plastome assemblies

Illumina paired-end sequencing produced 474,002 and 1,092,236 raw reads for Circaeaster and Kingdonia, respectively. The mean coverage of the plastome was 392.3× for Circaeaster, and 926.4× for Kingdonia. For both Circaeaster and Kingdonia, assembly yielded a single scaffold comprising the entire plastome sequence. Junction regions between the IR and Single-Copy regions were confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing (C8-C11 and K5-K8 in Additional file 1). Assembly statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the plastid genomes of Circaeaster agrestis and Kingdonia uniflora

| Circaeaster agrestis | Kingdonia uniflora | |

|---|---|---|

| Total plastome length (bp) | 151,033 | 147,378 |

| IR length (bp) | 28,023 | 30,916 |

| SSC length (bp) | 16,857 | 4857 |

| LSC length (bp) | 78,130 | 80,689 |

| Absent genes | accD | ndhC, ndhF, ndhI, ndhG |

| Pseudogenes | ΨinfA | ΨndhA, ΨndhB, ΨndhD, ΨndhH, ΨndhK |

| Overall G/C content (%) | 38.2 | 37.8 |

| Average depth of coverage | 392.3× | 926.4× |

| Number of plastid reads | 474,002 | 1,092,236 |

| Read length (bp) | 125 | 125 |

| Genes with one intron | trnK-UUU, trnG-UCC, trnL-UAA, trnV-UAC, trnI-GAU, trnA-UGC, petB, petD, atpF, ndhA, ndhB, rpl16, rpoC1, rps16 | trnK-UUU, trnG-UCC, trnL-UAA, trnV-UAC, trnI-GAU, trnA-UGC, petB, petD, atpF, rpl16, rpoC1, rps16 |

| Genes with two introns | rps12, clpP, ycf3 | rps12, clpP, ycf3 |

| GenBank accession number | KY908400 | KY908401 |

Structure and gene content of the Circaeaster and Kingdonia plastomes

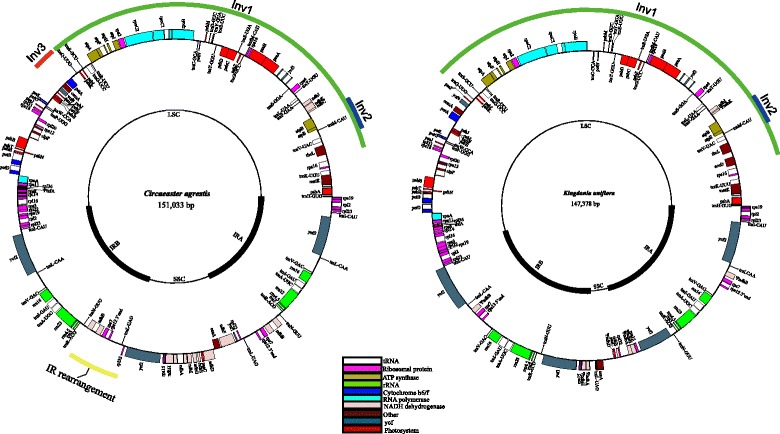

The plastome size of Circaeaster agrestis is 151,033 bp and that of Kingdonia uniflora is 147,378 bp (Fig. 1). Both plastomes possess the typical quadripartite structure of angiosperms, although both also contain several remarkable structural rearrangements. Most notably, a large ~49 kb inversion in the LSC region, including all genes from trnQ-UUG to rbcL/accD (accD is absent from Circaeaster) is present in both plastomes (Figs. 1, 2). In addition, both plastomes also share a much smaller inversion (~3.5 kb) involving all four genes from atpB to trnV-UAC (Figs. 1, 2). Circaeaster also possesses a number of other unique structural changes, including a ~ 3.5 kb inversion involving all four genes from psaI to petA (Figs. 1, 2) and a highly unusual IR structure. Specifically, the following changes have occurred within the IR of Circaeaster: (1) ndhB, rps7, and the 3′ end of rps12 have shifted to a position between trnN-GUU and ycf1 (compared to their typical positions between trnL-CAA and trnV-GAC in nearly all other angiosperms); (2) rpl32 and trnL-UAG are within the IR (rather than in the SSC region as in nearly all other angiosperms), and (3) ycf1 is almost entirely outside the IR (rather than having ~1000 bp of ycf1 within the IR, as is more typical of angiosperms). Within Kingdonia, the IR/SSC boundary has shifted to include all of ycf1, rps15, ΨndhH, and ΨndhA. In both plastomes, there are unusual arrangements of rpl32 and trnL-UAG, which in almost all other angiosperms are found adjacent to each other on the same strand within the SSC. The endpoints of these inversions were confirmed in both plastomes via PCR and Sanger sequencing using custom-designed primers (Additional files 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Plastome maps of Circaeaster agrestis and Kingdonia uniflora. IR, inverted repeat; LSC, large single-copy region; SSC, small single-copy region; Inv1, large inversion 1; Inv2, large inversion 2; Inv3, large inversion 3. The IR rearrangement is also indicated

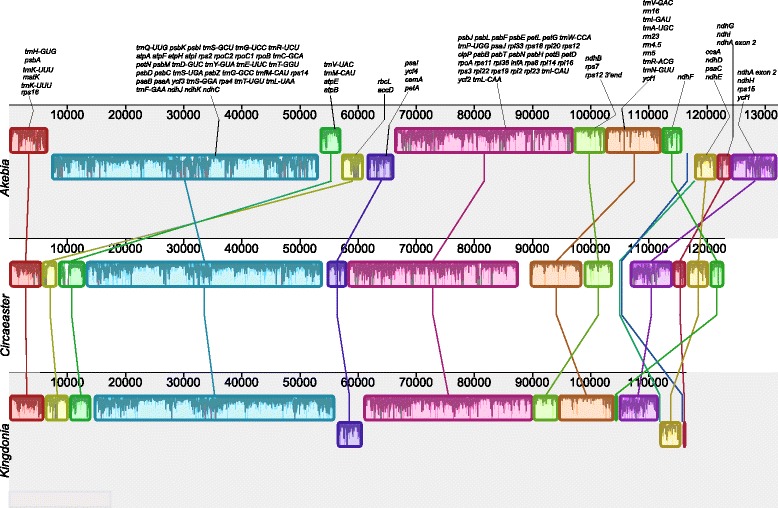

Fig. 2.

ProgressiveMauve alignment among Akebia, Circaeaster and Kingdonia showing the structural rearrangements in Circaeaster and Kingdonia. Colored blocks represent locally collinear blocks (LCBs) and are connected by lines to similarly colored LCBs, indicating homology

Overall, Circaeaster and Kingdonia were found to possess the typical gene and intron complement of angiosperms, with a few notable exceptions (Table 1). Both plastomes contain 30 tRNA genes and four rRNA genes, as is typical in angiosperms. The plastome of Circaeaster agrestis has 77 protein-coding genes and one pseudogene (ΨinfA, which is truncated to a length of 36 bp); accD is absent. The plastome of Kingdonia uniflora only has 70 protein-coding genes due to the loss or pseudogenization of nearly all ndh genes: four genes (ndhC, ndhF, ndhI and ndhG) were absent and five (ΨndhA, ΨndhB, ΨndhD, ΨndhH and ΨndhK) were identified as pseudogenes. More specifically, the second exon is absent from ΨndhA and ΨndhB, ΨndhD is severely truncated to 18 bp (vs. 1503 bp in Circaeaster), ΨndhH is truncated to 618 bp (vs. 1182 bp in Circaeaster) in length, and ΨndhK is only 237 bp (vs. 669 bp in Circaeaster) in length. The Ks values of these pseudogenes were calculated between Circaeaster and Kingdonia (Additional file 3). A total of 32 and 14 repeats ≥30 bp in length were found in the plastome of Circaeaster and Kingdonia, respectively (Additional files 4 and 5). For comparison, the number of repeats ≥30 bp in seven other Ranunculales species are as follows: (1) 17 in Akebia trifoliata (Thunb.) Koidz.; (2) 24 in Epimedium sagittatum (Sieb. & Zucc.) Maxim.; (3) 17 in Euptelea pleiosperma Hook.f. & Thomson; (4) 29 in Mahonia bealei (Fortune) Pynaert; (5) nine in Nandina domestica Thunb.; (6) nine in Papaver somniferum L.; and (7) eight in Stephania japonica (Thunb.) Miers (Additional file 6).

Phylogenetic analyses

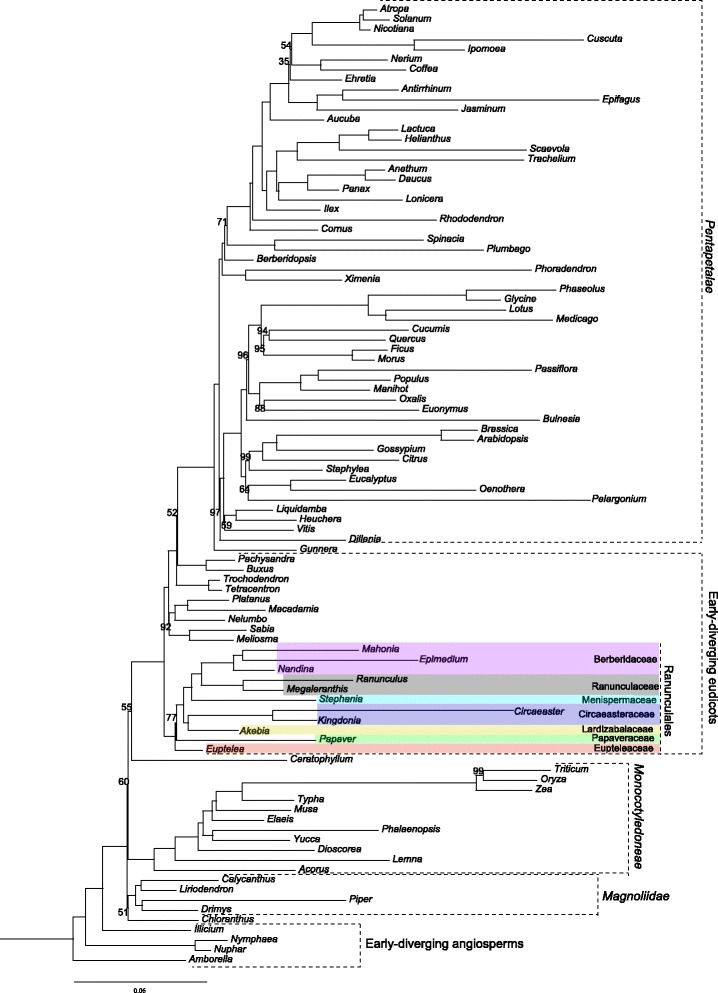

The final 79-gene, 99-taxon alignment used for ML analyses was 62,238 bp in length after character exclusion. The best partitioning scheme identified under the Bayesian information criteria (BIC) using relaxed clustering analysis in PartitionFinder (ln L = −1,173,388.00241; BIC 2353123.26941) contained 35 partitions. The tree with the highest ML score (ln L = −1,178,285.119460) produced by the 35-partition ML analysis (Fig. 3) shared an identical topology with the best tree from unpartitioned analysis (ln L = −1,200,753.541175) (Additional file 7), except for the relationships among Trochodendrales, Buxales and Gunneridae. The 35-partition analysis supported the sister relationship between Buxales and Gunneridae, but the support value was low (52%); while the unpartitioned analysis strongly supported the sister relationship between Trochodendrales and Gunneridae. Within Ranunculales, Eupteleaceae was found to be the earliest-diverging lineage, and Papaveraceae was sister to the clade comprised of Berberidaceae, Ranunculaceae, Menispermaceae, Lardizabalaceae and Circaeasteraceae. Lardizabalaceae and Circaeasteraceae formed a strongly supported clade that was sister to the clade of Berberidaceae, Ranunculaceae and Menispermaceae.

Fig. 3.

Phylogram of the best tree determined by RAxML for the 79-gene, 99-taxon data set using the 35-partition scheme recovered as optimal by PartitionFinder. Numbers associated with branches are ML bootstrap support values. Branches with no bootstrap values listed have 100% bootstrap support

Discussion

Plastome structure and gene content

The unusual structural rearrangements and gene losses (especially the loss of the ndh genes) detected in the two Circaeasteraceae plastomes represent the first reported among early-diverging eudicot plastomes, and hence shed important insight into the evolution of early eudicot plastomes. The fact that two of the observed inversions (the ~49 kb and ~3.5 kb inversions) are shared by Circaeaster and Kingdonia suggests that they predate the evolutionary split between these two genera. Although uncommon, relatively large inversions have been detected in a number of other angiosperm lineages and often serve as useful phylogenetic markers [50, 52–54]. Some of the best examples of relatively large inversions that are synapomorphies for clades of flowering plants include the 22.8 kb inversion shared by all Asteraceae except Barnadesioideae [53, 55], the 78 kb inversion shared by all Fabaceae subtribe Phaseolinae [56], and the 36 kb inversion present in all core genistoid legumes [50, 57]. Highly rearranged plastome structures also characterize a number of other angiosperm lineages, such as Campanulaceae, Geraniaceae, and the IR-lacking clade of Fabaceae, and these are associated with greatly elevated rates of molecular evolution and large numbers of short repeats [58]. In some cases the endpoints of large plastome inversions have been found to be associated with short inverted repeats (sIRs), although we did not detect sIRs in association with the inversion endpoints in Circaeaster or Kingdonia.

The IR regions of Circaeaster and Kingdonia are also structurally unique among angiosperms, with several rearrangements. The most unusual of these involves the transposition of the ndhB, rps7 and 3′ end of the rps12 gene to a point near the junction of the IRB and the SSC region (Fig. 1). These three genes form a transcriptional operon [59] and this operon is not disrupted in Circaeaster, nor does its transposition interrupt adjacent operons. The IR/SSC endpoints themselves are also rearranged in Circaeaster, with rpl32 and trnL-UAG within the IR and non-adjacent to ndhF, unlike almost all other angiosperms [54]. The IR boundaries of Kingdonia are also unusual for their expansion to include several genes that are normally in the SSC (e.g. ycf1, rps15), resulting in a much smaller and rearranged SSC (which is also influenced by the loss of ndh genes; see below). The exact sequence of rearrangements that could account for the unusual IR arrangements of Circaeasteraceae is clearly complicated and hence difficult to reconstruct. IR expansion and contraction is well-known in a number of other angiosperm lineages (e.g. [45]), including within early-diverging eudicots, which have been found to possess a number of expansions and contractions [23]. Given the expansions and rearrangements observed in Circaeaster and Kingdonia, neither fit into any of the six IR types for early-diverging eudicots delineated in Sun et al. [23], and thus we designate two new early-diverging eudicot IR types for Circaeaster (type G) and Kingdonia (type H) (Fig. 1).

Usually, gene content is highly conserved among photosynthetic angiosperm plastomes [50, 60], but in Circaeasteraceae, a number of genes have been lost or pseudogenized, each of which has been found to be lost repeatedly across angiosperms. For example, the loss of accD in Circaeaster is mirrored in a number of other lineages where accD is pseudogenized or absent, e.g., grasses [61], Lobeliaceae [62], Campanulaceae [52, 63, 64], Acorus [65], Oleaceae [66], Pelargonium [67], and Lolium perenne [68]. Likewise, infA is also known to be a pseudogene in numerous other angiosperms, including two Ranunculales (Ranunculus macranthus and Epimedium sagittatum) [23], tobacco [69], and numerous rosids [70]. Whether accD or infA have been transferred to the nucleus in Circaeaster is unknown.

The loss or pseudogenization of nearly all ndh genes from Kingdonia has also been observed in a number of other land plants. The ndh genes encode subunits of the plastid NDH (NADH dehydrogenase-like) complex, which permits cyclic electron flow associated with Photosystem I and hence facilitates chlororespiration [71, 72]. Although the NDH complex is widely retained across land plants, it has been found to be dispensable under optimal growth conditions and the plastid ndh genes have been lost in a number of autotrophic and heterotrophic lineages [72, 73]. For example, the plastid ndh loci have been lost or pseudogenized en masse from parasitic plants such as Orobanchaceae and Cuscuta (Convolvulaceae) [74–76], from mycoheterotrophs including several orchids [77] and Petrosavia (Petrosaviaceae) [78], and from autotrophs including Gnetales, conifers, Najas (Hydrocharitaceae), Carnegiea (Cactaceae), and Erodium (Geraniaceae) [79–84]. It is not clear whether the ndh genes in Kingdonia have been transferred to the nucleus or whether their loss represents the complete loss of the NDH complex, but in any case Kingdonia is the only known early-diverging eudicot that has experienced ndh pseudogenization and loss.

Moreover, the loss of the ndh genes in Kingdonia accounts for the smaller overall size of the Kingdonia plastome and may have also played an indirect role in the expansion of the IR of Kingdonia. The complete loss of ndhF, which normally occupies a position immediately adjacent to the IRB/SSC boundary, may have led to instability of the IR/SSC boundaries, leading to rearrangements of the SSC and IR. This hypothesis is supported by other recent studies in orchids [77] and Najas flexilis [82] where ndhF loss is associated with shifts in the IR/SSC boundary.

Phylogeny of Ranunculales

The circumscription of Ranunculales was long controversial (e.g. [3, 4, 9, 10, 85, 86]), but molecular phylogenetics has clarified the delimitation of Ranunculales to Berberidaceae, Circaeasteraceae, Eupteleaceae, Lardizabalaceae, Menispermaceae, Papaveraceae, and Ranunculaceae [1, 5, 6, 26, 29, 31, 32, 36, 38]. While the expansion of Circaeasteraceae to include Kingdonia is accepted by a majority of taxonomists [1], the rank and position of Kingdonia have long been in dispute [38]. The complete plastome sequence data strongly support the sister relationship between Kingdonia and Circaeaster, in concordance with previous molecular results [25, 26, 31, 32, 36, 38, 87]. The two inversions and the rare, open dichotomous leaf venation shared by these taxa are good synapomorphies that additionally support the placement of Circaeaster and Kingdonia in one family.

Conclusions

The plastomes of Circaeaster agrestis and Kingdonia uniflora provide the first reference genome sequences for Circaeasteraceae, which will enrich the sequence resources of plastomes in early-diverging eudicots. The unusual rearrangements including large inversions and unusual IR structure detected in the Circaeasteraceae plastomes will help us better characterize plastome structural evolution in early-diverging eudicots. Phylogenetic analyses of the 79-gene, 99-taxon data set confirmed the position of Circaeasteraceae in Ranunculales, with maximum support as sister to Lardizabalaceae. The two Circaeasteraceae plastomes will also be of benefit for further phylogenomic analyses within early-diverging eudicots.

Methods

Taxon sampling, chloroplast DNA isolation, high-throughput sequencing

Fresh leaves of Circaeaster agrestis were collected from Shennongjia, Hubei Province, China, in 2015, and from Kingdonia uniflora in Meixian, Shanxi Province, China, in 2016. Voucher specimens (Circaeaster agrestis: Y.X. Sun 1510; Kingdonia uniflora: Y.X. Sun 1606) were deposited at the Herbarium of Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences (HIB). For both species, high-quality chloroplast DNA was obtained following the plastid DNA extraction method of Shi et al. [88]. The sequencing libraries were constructed and quantified following the methods introduced by Sun et al. [23]. For both plastomes, a 500-bp DNA TruSeq Illumina (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) sequencing library was constructed using 2.5–5.0 ng sonicated chloroplast DNA as input. Libraries were quantified using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and by real-time quantitative PCR. Libraries were then multiplexed, and 2 × 125 bp sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform at the Beijing Genomics Institute.

Plastome assembly, annotation, and structural analyses

Following Sun et al. [23], duplicate reads, adapter-contaminated reads, and reads with more than five Ns were filtered out. Remaining, high-quality reads were assembled into contigs with a minimum length of 1000 bp using CLC Genomics Workbench with default parameters, except for a word size value of 60.

Plastomes were annotated using DOGMA [89] and through comparison with the sequences of published early-diverging eudicot plastomes. Physical maps were drawn using GenomeVx [90], followed by subsequent manual editing with Adobe Illustrator CS5. Boundaries for tRNAs were identified with tRNAscan-SE 1.21 [91] and confirmed by comparison with available early-diverging eudicot plastome sequences. The finished genomes were deposited in GenBank (Table 1).

To investigate plastome structural evolution, whole plastome alignment between Circaeasteraceae and representatives of other early-diverging eudicot families was performed with ProgressiveMauve v 2.4.0 [92], including only one copy of the IR (IRB), and locally collinear blocks (LCBs) were identified. Because the 18 reported early-diverging eudicot plastomes in Sun et al. [23] share the same gene order, and because Circaeasteraceae was resolved as sister to Akebia in present research, the Akebia plastome was used as the reference sequence for ProgressiveMauve comparisons. mVISTA [93] was employed to generate sequence identity plots. The number and location of repeat elements in the plastomes of Circaeaster and Kingdonia as well as seven other Ranunculales species (Akebia trifoliata, Epimedium sagittatum, Euptelea pleiosperma, Berberis bealei, Nandina domestica, Papaver somniferum and Stephania japonica) were determined by REPuter [94], with a minimum size of 30 bp and a Hamming distance of 1. Before performing the analysis, one copy of the IR was removed.

Phylogenetic analyses

All protein-coding regions were extracted from the plastomes of Circaeaster and Kingdonia. These sequences were then added manually to the 97-taxon alignment of Sun et al. [23], resulting in a data set with complete coverage of early-diverging eudicot families sensu APG IV [1]. GenBank information for all plastomes used for present phylogenetic analyses can be found in Additional file 8. Regions of ambiguous alignment and sites with more than 80% missing data were excluded from the alignment.

Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were conducted using RAxML version 7.4.2 [95], under the general time-reversible (GTR) substitution model and the Γ model of rate heterogeneity. We conducted both unpartitioned and partitioned analyses. PartitionFinder version 1.1.1 [96] was used to select the best-fit partitioning scheme, considering all 237 possible gene-by-codon position partitions (79 genes × 3 codon positions). For both ML analyses, a single set of branch lengths for all partitions was used. Ten independent ML searches were conducted and bootstrap support was estimated with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Additional files

Sanger chromatograms of primer products C1-C11 and K1-K8. (ZIP 2226 kb)

Primers designed for verifying endpoints of plastome structural rearrangements. (DOC 54 kb)

Ks values calculation of five pseudogenes in Kingdonia. (DOC 29 kb)

Repeats ≥30 bp in the plastome of Circaeaster. F, forward; P, palindromic. (DOC 51 kb)

Repeats ≥30 bp in the plastome of Kingdonia. F, forward; P, palindromic. (DOC 42 kb)

Repeats ≥30 bp in the plastomes of seven other Ranunculales species. (DOC 30 kb)

Phylogram of the best tree determined by RAxML for the 79-gene, 99-taxon data set with no data partitions. Numbers associated with branches are ML bootstrap support values. Branches with no bootstrap values listed have 100% bootstrap support. (PDF 204 kb)

List of taxa included in phylogenetic analyses. (DOC 67 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gen-lu Bai for helping with collecting plant materials.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31600176, 31370242 and 31370223), and NSTIPC (2013FY111200) and SPRPCAS (XDA13020500).

Availability of data and materials

All sequences used in this study are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (see Additional file 8). Additionally, two plastomes sequenced in this study have been deposited in the NCBI genome database (Accession numbers: see Methods).

Authors’ contributions

YS, HW and JL conceived and designed the study. YS performed de novo assembly, genome annotation, phylogenetic and other analyses. YS and MM drafted the manuscript. YS, NL and AK performed the experiments. AM, LY and SJ collected the leaf materials. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3956-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Jianqiang Li, Email: lijq@wbgcas.cn.

Hengchang Wang, Email: hcwang@wbgcas.cn.

References

- 1.Angiosperm Phylogeny Group An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot J Linn Soc. 2016;181:1–20. doi: 10.1111/boj.12385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahlgren G. A revised system of classification of the angiosperms. Bot J Linn Soc. 1980;80:91–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1980.tb01661.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlgren R. General aspects of angiosperm evolution and macro-systematics. Nord J Bot. 1983;3:119–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.1983.tb01448.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takhtajan A. Diversity and classification of flowering plants. New York: Columbia University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angiosperm Phylogeny Group An ordinal classification for the families of flowering plants. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 1998;85:531–553. doi: 10.2307/2992015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angiosperm Phylogeny Group An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II. Bot J Linn Soc. 2003;141:399–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1095-8339.2003.t01-1-00158.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchinson J. The families of flowering plants arranged according to a new system based on their probable phylogeny. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorne RF. Classification and geography of the flowering plants. Bot Rev. 1992;58:225–348. doi: 10.1007/BF02858611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubitzki K, Rohwer JC, Bittrich V. The families and genera of vascular plants II. Berlin: Springer; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu ZY, Lu AM, Tang YC, Chen ZD, Li DZ. Synopsis of a new “polyphyletic–polychronic–polytopic” system of the angiosperms. Acta Phytotaxon Sin. 2002;40:289–322. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crane PR, Friis EM, Pedersen KR. Paleobotanical evidence on the early radiation of magnoliid angiosperms. Plant Syst Evol [Supplement l] 1994;8:51–72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drinnan AN, Crane PR, Hoot SB. Patterns of floral evolution in the early diversification of non-magnoliid dicotyledons (eudicots) Plant Syst Evol [Supplement 8] 1994;8:93–122. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore MJ, Dhingra A, Soltis PS, Shaw R, Farmerie WG, Folta KM, Soltis DE. Rapid and accurate pyrosequencing of angiosperm plastid genomes. BMC Plant Biol. 2006;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen DR, Dastidar SG, Cai ZQ, Penaflor C, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Phylogenetic and evolutionary implications of complete chloroplast genome sequences of four early-diverging angiosperms: Buxus (Buxaceae), Chloranthus (Chloranthaceae), Dioscorea (Dioscoreaceae), and Illicium (Schisandraceae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;45:547–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raubeson LA, Peery R, Chumley TW, Dziubek C, Fourcade HM, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Comparative chloroplast genomics: analyses including new sequences from the angiosperms Nuphar advena and Ranunculus macranthus. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YK, Park CW, Kim KJ. Complete chloroplast DNA sequence from a Korean endemic genus, Megaleranthis saniculifolia, and its evolutionary implications. Mol Cells. 2009;27:365–381. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma J, Yang BX, Zhu W, Sun LL, Tian JK, Wang X. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Mahonia bealei (Berberidaceae) reveals a significant expansion of the inverted repeat and phylogenetic relationship with other angiosperms. Gene. 2013;528:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun YX, Moore MJ, Meng AP, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Li JQ, Wang HC. Complete plastid genome sequencing of Trochodendraceae reveals a significant expansion of the inverted repeat and suggests a Paleogene divergence between the two extant species. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nock CJ, Baten A, King GJ. Complete chloroplast genome of Macadamia integrifolia confirms the position of the Gondwanan early-diverging eudicot family Proteaceae. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:S13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-S9-S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu ZH, Gui ST, Quan ZW, Pan L, Wang SZ, Ke WD, Liang DQ, Ding Y. A precise chloroplast genome of Nelumbo nucifera (Nelumbonaceae) evaluated with sanger, Illumina MiSeq, and PacBio RS II sequencing platforms: insight into the plastid evolution of early-diverging eudicots. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:289. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0289-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim C, Kim G, Baek S, Han S, Yu H, Mun J. The complete chloroplast genome of Aconitum chiisanense Nakai (Ranunculaceae) Mitochondr DNA. 2015;28:1–2. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1110805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S, Jansen R, Park S. Complete plastome sequence of Thalictrum coreanum (Ranunculaceae) and transfer of the rpl32 gene to the nucleus in the ancestor of the subfamily Thalictroideae. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:40. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0432-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun YX, Moore MJ, Zhang SJ, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Zhao TT, Meng AP, Li XD, Li JQ, Wang HC. Phylogenomic and structural analyses of 18 complete plastomes across nearly all families of early-diverging eudicots, including an angiosperm-wide analysis of IR gene content evolution. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016;96:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Du L, Liu A, Chen J, Wu L, Hu W, Zhang W, Kim K, Lee S, Yang T, Wang Y. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of five Epimedium species: lights into phylogenetic and taxonomic analyses. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:306. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoot SB, Crane PR. Interfamilial relationships in the Ranunculidae based on molecular systematics. Plant Syst Evol (Suppl.) 1995;9:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoot SB, Magallón S, Crane PR. Phylogeny of basal eudicots based on three molecular data sets: atpB, rbcL, and 18S nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 1999;86:1–32. doi: 10.2307/2666215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiu YL, Dombrovska O, Lee J, Li L, Whitlock BA, Bernasconi-Quadroni F, Rest JS, Davis CC, Borsch T, Hilu KW, Renner SS, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Zanis MJ, Cannone JJ, Gutell RR, Powell M, Savolainen V, Chatrou LW, Chase MW. Phylogenetic analysis of basal angiosperms based on nine plastid, mitochondrial, and nuclear genes. Int J Plant Sci. 2005;166:815–842. doi: 10.1086/431800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu YL, Li L, Hendry TA, Li R, Taylor DW, Issa MJ, Ronen AJ, Vekaria ML, White AM. Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of the mitochondrial genes. Taxon. 2006;55:837–856. doi: 10.2307/25065680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savolainen V, Fay MF, Albach DC, Backlund A, van der Bank M, Cameron KM, Johnson SA, Lledó MD, Pintaud JC, Powell M, Sheanan MC, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Weston P, Whitten WM, Wurdack KJ, Chase MW. Phylogeny of the eudicots: a nearly complete familial analysis based on rbcL gene sequences. Kew Bull. 2000;55:257–309. doi: 10.2307/4115644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savolainen V, Chase MW, Hoot SB, Morton CM, Soltis DE, Bayer C, Fay MF, De Brujin A, Sullivan S, Qiu YL. Phylogenetics of flowering plants based upon a combined analysis of plastid atpB and rbcL gene sequences. Syst Biol. 2000;49:306–362. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/49.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Chase MW, Mort ME, Albach DC, Zanis M, Savolainen V, Hahn WH, Hoot SB, Fay MF, Axtell M, Swensen SM, Nixon KC, Farris JS. Angiosperm phylogeny inferred from a combined data set of 18S rDNA, rbcL, and atpB sequences. Bot J Linn Soc. 2000;133:381–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2000.tb01588.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soltis DE, Senters AE, Zanis MJ. Kim S, Thompson JD, Soltis PS, Ronse de Craene LP, Endress PK, Farris JS. Gunnerales are sister to other core eudicots: implications for the evolution of pentamery. Am J Bot. 2003;90:461–470. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nickrent DL, Blarer A, Qiu YL, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Zanis M. Molecular data place Hydnoraceae with Aristolochiaceae. Am J Bot. 2002;89:1809–1817. doi: 10.3732/ajb.89.11.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilu KW, Borsch T, Müller K, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Savolainen V, Chase MW, Powell MP, Alice LA, Evans R, Sauquet H, Neinhuis C, Slotta TAB, Rohwer JG, Campbell CS, Chatrou LW. Angiosperm phylogeny based on matK sequence information. Am J Bot. 2003;90:1758–1776. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.12.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zanis MJ, Soltis PS, Qiu YL, Zimmer E, Soltis DE. Phylogenetic analyses and perianth evolution in basal angiosperms. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 2003;90:129–150. doi: 10.2307/3298579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Zanis MJ, Suh Y. Phylogenetic relationships among early-diverging eudicots based on four genes: were the eudicots ancestrally woody? Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;31:16–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Worberg A, Quandt D, Barnikse AM, Löhne C, Hilu KW, Borsch T. Towards understanding early eudicot diversification: insights from rapidly evolving and non-coding DNA. Org Divers Evol. 2007;7:55–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ode.2006.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang W, Lu A, Ren Y, Endress ME, Chen Z. Phylogeny and classification of Ranunculales: evidence from four molecular loci and morphological data. Perspect Plant Ecol. 2009;11:81–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soltis DE, Smith SA, Cellinese N, Wurdack KJ, Tank DC, Brockington SF, Refulio-Rodriguez NF, Walker JB, Moore MJ, Carlsward BS, Bell CD, Latvis M, Crawley S, Black C, Diouf D, Xi Z, Rushworth CA, Gitzendanner MA, Sytsma KJ, Qiu YL, Hilu KW, Davis CC, Sanderson MJ, Beaman RS, Olmstead RG, Judd WS, Donoghue MJ, Soltis PS. Angiosperm phylogeny: 17 genes, 640 taxa. Am J Bot. 2011;98:704–730. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruhlman TA, Jansen RK. The plastid genomes of flowering plants. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1132:3–38. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-995-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daniell H, Lin CS, Yu M, Chang WJ. Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 2016;17:134. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer JD, Stein DB. Conservation of chloroplast genome structure among vascular plants. Curr Genet. 1986;10:823–833. doi: 10.1007/BF00418529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goulding SE, Olmstead RG, Morden CW, Wolfe KH. Ebb and flow of the chloroplast inverted repeat. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:195–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02173220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plunkett GM, Downie SR. Expansion and contraction of the chloroplast inverted repeat in Apiaceae subfamily Apioideae. Syst Bot. 2000;25:648–667. doi: 10.2307/2666726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Downie SR, Jansen RK. A comparative analysis of whole plastid genomes from the Apiales: expansion and contraction of the inverted repeat, mitochondrial to plastid transfer of DNA, and identification of highly divergent noncoding regions. Syst Bot. 2015;40:336–351. doi: 10.1600/036364415X686620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmer JD, Herbon LA. Plant mitochondrial-DNA evolves rapidly in structure, but slowly in sequence. J Mol Evol. 1988;28:87–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02143500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perry AS, Brennan S, Murphy DJ, Kavanagh TA, Wolfe KH. Evolutionary re-organisation of a large operon in adzuki bean chloroplast DNA caused by inverted repeat movement. DNA Res. 2002;9:157–162. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.5.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magee AM, Aspinall S, Rice DW, Cusack BP, Sémon M, Perry AS, Stefanović S, Milbourne D, Barth S, Palmer JD, Gray JC, Kavanagh TA, Wolfe KH. Localized hypermutation and associated gene losses in legume chloroplast genomes. Genome Res. 2010;20:1700–1710. doi: 10.1101/gr.111955.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tangphatsornruang S, Sangsrakru D, Chanprasert J, Uthaipaisanwong P, Yoocha T, Jomchai N, Tragoonrung S. The chloroplast genome sequence of mungbean (Vigna radiata) determined by highthroughput pyrosequencing: structural organization and phylogenetic relationships. DNA Res. 2010;17:11–22. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin E, Rousseau-Gueutin M, Cordonnier S, Lima O, Michon-Coudouel S, Naquin D, de Carvalho JF, Malika A, Salmon A, Aïnouche A. The first complete chloroplast genome of the Genistoid legume Lupinus luteus: evidence for a novel major lineage-specific rearrangement and new insights regarding plastome evolution in the legume family Guillaume. Ann Bot. 2014;113:1197–1210. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jansen RK, Cai Z, Raubeson LA, Daniell H, Depamphilis CW, Leebens-Mack J, Müller KF, Guisinger-Bellian M, Haberle RC, Hansen AK, Chumley TW, Lee S, Peery R, JR MN, Kuehl JV, Boore JL. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19369–19374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cosner ME, Raubeson LA, Jansen RK. Chloroplast DNA rearrangements in Campanulaceae: phylogenetic utility of highly rearranged genomes. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim KJ, Choi KS, Jansen RK. Two chloroplast DNA inversions originated simultaneously during the early evolution of the sunflower family (Asteraceae) Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1783–1792. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raubeson LA, Jansen RK. Chloroplast genomes of plants. In: Henry R, editor. Diversity and evolution of plants-genotypic variation in higher plants. Oxfordshire: CABI Publishing; 2005. pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jansen RK, Palmer JD. A chloroplast DNA inversion marks an ancient evolutionary split in the sunflower family (Asteraceae) P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5818–5822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bruneau A, Doyle JJ, Palmer JD. A chloroplast DNA structural mutation as a subtribal character in the Phaseoleae (Leguminosae) Syst Bot. 1990;15:378–386. doi: 10.2307/2419351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crisp M, Gilmore S, van Wyk B. Molecular phylogeny of the Genistoid tribes of Papilionoid legumes. London: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jansen RK, Ruhlman TA. Plastid genomes of seed plants. In: Bock R, Knoop V, editors. Genomics of chloroplast and mitochondria. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woodbury NW, Roberts LL, Palmer JD, Thompson WF. A transcription map of the pea chloroplast genome. Curr Genet. 1988;14:75–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00405857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Timmis JN, Ayliffe MA, Huang CY, Martin W. Endosymbiotic gene transfer: organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrg1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katayama H, Ogihara Y. Phylogenetic affinities of the grasses to other monocots as revealed by molecular analysis of chloroplast DNA. Curr Genet. 1996;29:5. doi: 10.1007/BF02426962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knox EB, Palmer JD. The chloroplast genome arrangement of lobelia thuliniana lobeliaceae: expansion of the inverted repeat in an ancestor of the campanulales. Plant Syst Evol. 1999;214:49–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00985731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cosner ME, Jansen RK, Palmer JD, Downie SR. The highly rearranged chloroplast genome of Trachelium caeruleum (Campanulaceae): multiple inversions, inverted repeat expansion and contraction, transposition, insertions/deletions, and several repeat families. Curr Genet. 1997;31:419–429. doi: 10.1007/s002940050225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haberle RC, Fourcade HM, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Extensive rearrangements in the chloroplast genome of Trachelium caeruleum are associated with repeats and tRNA genes. J Mol Evol. 2008;66:350–361. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goremykin VV, Holland B, Hirsch-Ernst KI, Hellwig FH. Analysis of Acorus Calamus chloroplast genome and its phylogenetic implications. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1813–1822. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee H, Jansen RK, Chumley TW, Kim K. Gene relocations within chloroplast genomes of Jasminum and Menodora (Oleaceae) are due to multiple, overlapping inversions. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1161–1180. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chumley TW, Palmer JD, Mower JP, Matthew Fourcade H, Calie PJ, Boore J, Jansen RK. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pelargonium x hortorum: organization and evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:2175–2190. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Diekmann K, Hodkinson TR, Wolfe KH, van den Bekerom R, Dix P, Barth S. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a major allogamous forage species, perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) DNA Res. 2009;16:165–176. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shinozaki K, Ohme M, Tanaka M, Wakasugi T, Hayshida N, Matsubayashi T, Zaita N, Chunwongse J, Obokata J, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Ohto C, Torazawa K, Meng BY, Sugita M, Deno H, Kamogashira T, Yamada K, Kusuda J, Takaiwa F, Kato A, Tohdoh N, Shimada H, Sugiura M. The complete nucleotide sequence of the tobacco chloroplast genome: its gene organization and expression. EMBO J. 1986;5:2043–2049. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Millen RS, Olmstead RG, Adams KL, Palmer JD, Lao NT, Heggie L, Kavanagh TA, Hibberd JM, Gray JC, Morden CW, Calie PJ, Jermiin LS, Wolfe KH. Many parallel losses of infA from chloroplast DNA during angiosperm evolution with multiple independent transfers to the nucleus. Plant Cell. 2001;13:645–658. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martin M, Sabater B. Plastid ndh genes in plant evolution. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2010;48:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ruhlman TA, Chang WJ, Chen JJW, Huang YT, Chan MT, Zhang J, Liao DC, Blazier JC, Jin X, Shih MC, Jansen RK, Lin CS. NDH expression marks major transitions in plant evolution and reveals coordinate intracellular gene loss. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:100. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0484-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burrows PA, Sazanov LA, Svab Z, Maliga P, Nixon PJ. Identification of a functional respiratory complex in chloroplasts through analysis of tobacco mutants containing disrupted plastid ndh genes. EMBO J. 1998;17:868–876. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Funk HT, Berg S, Krupinska K, Maier UG, Krause K. Complete DNA sequences of the plastid genomes of two parasitic flowering plant species, Cuscuta reflexa and Cuscuta gronovii. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haberhausen G, Zetsche K. Functional loss of all ndh genes in an otherwise relatively unaltered plastid genome of the holoparasitic flowering plant Cuscuta reflexa. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;24:217–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00040588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wolfe KH, Morden CW, Palmer JD. Function and evolution of a minimal plastid genome from a nonphotosynthetic parasitic plant. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10648–10652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim HT, Kim JS, Moore MJ, Neubig KM, Williams NH, Whitten WM, Kim JH. Seven new complete plastome sequences reveal rampant independent loss of the ndh gene family across orchids and associated instability of the inverted repeat/small single-copy region boundaries. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Logacheva MD, Schelkunov MI, Nuraliev MS, Samigullin TH, Penin AA. The plastid genome of mycoheterotrophic monocot Petrosavia stellaris exhibits both gene losses and multiple rearrangements. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:238–246. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Blazier J, Guisinger MM, Jansen RK. Recent loss of plastid-encoded ndh genes within Erodium (Geraniaceae) Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Braukmann TWA, Kuzmina M, Stefanovic S. Loss of all plastid ndh genes in Gnetales and conifers: extent and evolutionary significance for the seed plant phylogeny. Curr Genet. 2009;55:323–337. doi: 10.1007/s00294-009-0249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McCoy SR, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Raubeson LA. The complete plastid genome sequence of Welwitschia mirabilis: an unusually compact plastome with accelerated divergence rates. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peredo EL, King UM, Les DH. The plastid genome of Najas flexilis: adaptation to submersed environments is accompanied by the complete loss of the NDH complex in an aquatic angiosperm. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sanderson MJ, Copetti D, Búrquez A, Bustamante E, Charboneau JLM, Eguiarte LE, Kumar S, Lee HO, Lee J, McMahon M, Steele K, Wing R, Yang TJ, Zwickl D, Wojciechowski MF. Exceptional reduction of the plastid genome of saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea): loss of the ndh gene suite and inverted repeat. Am J Bot. 2015;102:1115–1127. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1500184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wakasugi T, Tsudzuki J, Ito S, Nakashima K, Tsudzuki T, Sugiura M. Loss of all ndh genes as determined by sequencing the entire chloroplast genome of the black pine Pinus thunbergii. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9794–9798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cronquist A. The evolution and classification of flowering plants. second. New York: New York Botanical Garden; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thorne RF. An updated classification of the class Magnoliopsida (“Angiospermae”) Bot Rev. 2007;73:67–182. doi: 10.1663/0006-8101(2007)73[67:AUCOTC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oxelman B, Lidén M. The position of Circaeaster – evidence from nuclear ribosomal DNA. Plant Syst Evol (Suppl) 1995;9:189–193. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shi C, Hu N, Huang H, Gao J, Zhao Y, Gao L. An improved chloroplast DNA extraction procedure for whole plastid genome sequencing. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Conant GC, Wolfe KH. GenomeVx: simple web-based creation of editable circular chromosome maps. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:861–862. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schattner P, Brooks AN, Lowe TM. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W686–W689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. ProgressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W273–W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lanfear R, Calcott B, Ho SYW, Guindon S. PartitionFinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1695–1701. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sanger chromatograms of primer products C1-C11 and K1-K8. (ZIP 2226 kb)

Primers designed for verifying endpoints of plastome structural rearrangements. (DOC 54 kb)

Ks values calculation of five pseudogenes in Kingdonia. (DOC 29 kb)

Repeats ≥30 bp in the plastome of Circaeaster. F, forward; P, palindromic. (DOC 51 kb)

Repeats ≥30 bp in the plastome of Kingdonia. F, forward; P, palindromic. (DOC 42 kb)

Repeats ≥30 bp in the plastomes of seven other Ranunculales species. (DOC 30 kb)

Phylogram of the best tree determined by RAxML for the 79-gene, 99-taxon data set with no data partitions. Numbers associated with branches are ML bootstrap support values. Branches with no bootstrap values listed have 100% bootstrap support. (PDF 204 kb)

List of taxa included in phylogenetic analyses. (DOC 67 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All sequences used in this study are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (see Additional file 8). Additionally, two plastomes sequenced in this study have been deposited in the NCBI genome database (Accession numbers: see Methods).