Abstract

The impact of pesticide residues on human health is a worldwide problem, as human exposure to pesticides can occur through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact. Regulatory jurisdictions have promulgated the standard values for pesticides in residential soil, air, drinking water, and agricultural commodity for years. Until now, more than 19,400 pesticide soil regulatory guidance values (RGVs) and 5400 pesticide drinking water maximum concentration levels (MCLs) have been regulated by 54 and 102 nations, respectively. Over 90 nations have provided pesticide agricultural commodity maximum residue limits (MRLs) for at least one of the 12 most commonly consumed agricultural foods. A total of 22 pesticides have been regulated with more than 100 soil RGVs, and 25 pesticides have more than 100 drinking water MCLs. This research indicates that those RGVs and MCLs for an individual pesticide could vary over seven (DDT drinking water MCLs), eight (Lindane soil RGVs), or even nine (Dieldrin soil RGVs) orders of magnitude. Human health risk uncertainty bounds and the implied total exposure mass burden model were applied to analyze the most commonly regulated and used pesticides for human health risk control. For the top 27 commonly regulated pesticides in soil, there are at least 300 RGVs (8% of the total) that are above all of the computed upper bounds for human health risk uncertainty. For the top 29 most-commonly regulated pesticides in drinking water, at least 172 drinking water MCLs (5% of the total) exceed the computed upper bounds for human health risk uncertainty; while for the 14 most widely used pesticides, there are at least 310 computed implied dose limits (28.0% of the total) that are above the acceptable daily intake values. The results show that some worldwide standard values were not derived conservatively enough to avoid human health risk by the pesticides, and that some values were not computed comprehensively by considering all major human exposure pathways.

Keywords: pesticide regulation, pesticide exposure, human health risk assessment, health risk uncertainty bounds, environmental regulatory jurisdiction

1. Introduction

Pesticides are broadly applied in numerous agricultural, commercial, residential, and industrial applications to control and kill pests. They help society fight disease and increase agricultural productivity; however, pesticides can be transported into the air, water, soil, and biomass after numerous applications and can cause risks to the ecosystem and to human health. The impact of pesticide residues on human health is a worldwide problem, as human exposure to pesticides can occur through the ingestion of pesticide-contaminated water, food, or residential surface soil, the inhalation of pesticide-contaminated air, soil dust, or industrial vapor, and dermal contact with pesticide-contaminated water (swimming, showering, or raining), air, agricultural commodities, or soil. Worldwide jurisdictions have been working on regulating pesticide standard values for residential surface soil, residential air, drinking water, surface water, groundwater, and food for years.

Pesticide soil regulatory guidance values (RGVs) are applied by worldwide soil jurisdictions to control pesticide pollution in residential surface soil. Pesticide soil RGVs specified the maximum amount of a pesticide which might be present in the soil without prompting regulatory responses, such as surface or groundwater contamination by the transport of pesticides from surface soil, ecological risk, and adverse human health effects by exposure to soil pesticides. The most concerned and conservative pesticide soil RGVs are provided for residential surface soil, where children can be exposed to soil pesticides by the ingestion of soil, the inhalation of soil dust, or dermal contact. Although many worldwide regulatory jurisdictions have provided the RGVs in soil to protect human health, there is a lack of agreement on the pesticides that need to be regulated, as well as the magnitude of the pesticide soil RGVs which should be applied to a certain pesticide. For some of the most frequently regulated pesticides, the RGVs vary to above six orders of magnitude (i.e. 1,000,000) [1]. This variability implies that worldwide soil regulatory jurisdictions have hugely different views on the criteria which cause significant human health risks by residential surface soil pesticides. Other studies have also investigated soil RGVs, but have had their evaluations restricted to less-extensive sets of jurisdictions, such as the U.S. and European nations [2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

Drinking water supplies might be contaminated by pesticides as pesticide can be transferred into surface water or ground water systems, which are usually considered as important drinking water sources. The pesticides found in drinking water may have a potential impact on human health, depending on the amount and the toxicity of the pesticides and the frequency/length of human exposure to the contaminated drinking water. Similar to the pesticide soil RGVs, pesticide drinking water maximum concentration levels (MCLs) are also established by worldwide regulatory jurisdictions to specify the maximum allowable concentration of pesticides in drinking water to protect human health. The results indicate that there is little agreement on both how the pesticides should be regulated and what the magnitude of the MCLs applied to a certain pesticide should be among worldwide drinking water regulatory jurisdictions. The analysis [1] demonstrated that the MCLs of the most commonly regulated pesticides often vary by five, six, or even seven orders of magnitude, which also indicated that some extremely large pesticide MCL values are unlikely to protect human health. The California Department of Public Health (2013) [9] compared the MCLs to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standard. Among others [10,11], Bamidele (2015) studied the MCLs among the Canadian, European Union (EU), World Health Organization (WHO), U.S., and Nigerian national standards.

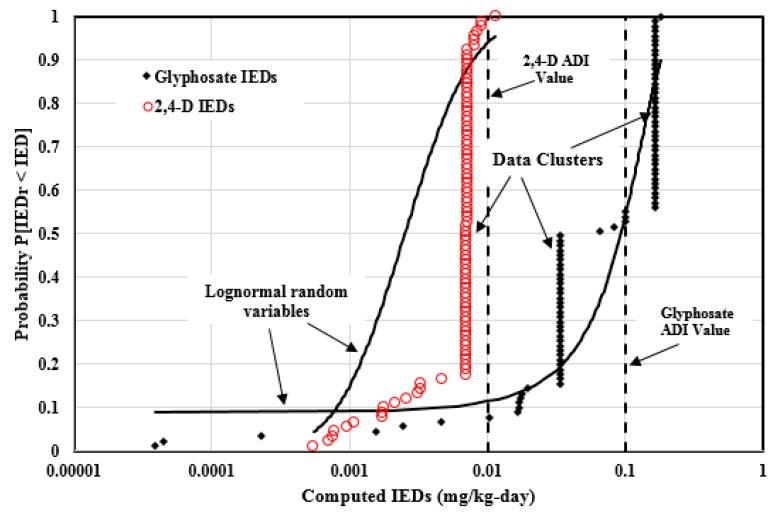

Since pesticides are directly applied on crops, fruits, and vegetables in most agricultural applications, infants, children, and adults can be exposed to pesticides by the ingestion of those pesticide-contaminated foods. Pesticide maximum residue limits (MRLs), which specify the maximum concentration of a pesticide that can exist in certain agricultural commodities, were regulated by many nations to promote good agricultural practice (GAP). Because food consumption varies by season, geology, culture, personal habit, economic status and crop availability, which all have impacts on human exposure to pesticides, it is crucial and challenging to develop pesticide MRLs for numerous agricultural commodities to protect human health. To evaluate the effectiveness of the protection from the pesticide MRLs for various agricultural foods, estimations of the most commonly consumed agricultural commodities and the ingestion rate are necessary. Therefore, an implied exposure dose (IED) was introduced in this research to convert the pesticide MRLs in the most consumed agricultural commodities into the pesticide exposure mass burden, and to compare with the toxicology data. The results indicated that many MRLs for the most widely used pesticides were set too high to protect human health.

Pesticides can exist in residential air by the evaporation of volatile and semi-volatile pesticides, such as organochlorine pesticides, from crops and residential surface soil. In addition, pesticides can be blown away from agricultural fields by the wind, and some fumigants (e.g., bromomethane) are released into the air in a gaseous form. Therefore, the regulation of pesticide standard values in the residential air is necessary to control human health risks through inhalation and dermal contact exposures, especially for volatile and semi-volatile pesticides. However, few worldwide jurisdictions have regulated pesticide air standard values, which means that people around the world are probably not protected by the pesticide air regulations, especially for some farmers and workers who frequently work in the agricultural field.

Human exposures to pesticide may also occurs through swimming in rivers, lakes, or pools where the water has been contaminated by pesticides, taking a shower when the water is being pumped from pesticide-contaminated ground water, getting wet from pesticide-contaminated rainwater, or handling pesticide-related products during work. Since the regulation of pesticides in these scenarios is important to control human health risks, and since these scenarios are the four most frequent human exposure pathways for pesticides, the pesticide standard values in major human exposure pathways which include residential soil, drinking water, agricultural commodities, and residential air were discussed in this research.

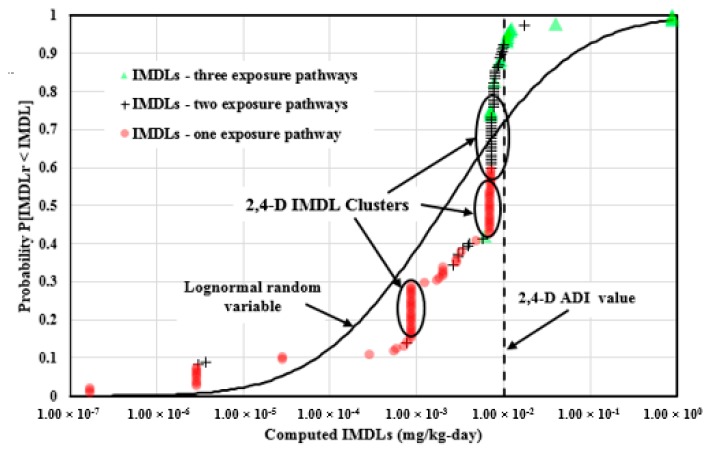

The standard values for pesticides for each human exposure pathway should be derived by laboratory toxicology data and human health risk models. Some uncertainty and marginal safety factors should also be applied to allow for additional exposure possibilities. As pesticide exposures in major exposure scenarios always happen simultaneously, it is necessary to derive and allocate pesticide standard values in major exposure pathways comprehensively. Therefore, the implied maximum dose limit (IMDL) was applied to compute the total maximum exposure mass burden for a certain pesticide from the pesticide standard values of the national jurisdictions in all major exposure pathways. The objectives of this research review are to evaluate current worldwide pesticide standard values in major exposures, examine whether those standard values can protect human health, and help environmental regulatory jurisdictions to rationalize their pesticide standard values by a scope of worldwide efforts.

2. Materials

The materials for this research review include two main parts; one is the pesticide which had been regulated with a certain residential soil RGV, drinking water MCL, agricultural commodity MRL, or residential air MCL, and the other is the worldwide regulatory jurisdiction which had promulgated a certain pesticide standard value in any of those major exposure pathways.

2.1. Pesticide

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2017) [12] defined a pesticide as a chemical compound that is used to kill pests, including insects, rodents, fungi and unwanted plants (weeds). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations defined a pesticide as any substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, or controlling any pest, including vectors of human or animal diseases, unwanted species of plants or animals causing harm during, or otherwise interfering with, the production, processing, storage, or marketing of food, agricultural commodities, wood and wood products, or animal feedstuffs, or which may be administered to animals for the control of insects, arachnids or other pests in or on their bodies.

Pesticides can be classified by target groups as acaricides, avicides, bactericides, herbicides, fungicides, insecticides, repellents, virucides, and so on. According to the chemical compositions of the active ingredients, pesticides can be categorized into four main groups: carbamates, organochlorines, organophosphorus, and pyrethrin and pyrethroids. WHO (2009) [13] classified pesticides by hazard as an extremely hazardous pesticide, a highly hazardous pesticide, a moderately hazardous pesticide, a slightly hazardous pesticide, and a pesticide which is unlikely to present an acute hazard. In addition, based on the mode of formulation, pesticides can be classified as emulsifiable concentrates, wettable powders, granules, baits, dust, and fumigants [14].

2.2. CAS No.

Because of the complex chemical structures and the chemical complexity of pesticides and their active ingredients, pesticides are often regulated by their trade names instead of the chemical nomenclature conventions. For example, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (2011) [15] listed 120 names for the pesticide “Lindane”, which include 30 chemical nomenclature names and 90 other trade names. Even worldwide jurisdictions have regulated pesticides by their local trade names in foreign languages, which has made it difficult to identify pesticides by their “names”. The Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number (CAS No.) by NIST and the common name by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPCA) were applied to identify pesticides in this research review, as each pesticide was assigned a unique CAS No. and a common name. It would be helpful and convenient to the public if a jurisdiction were to use the CAS No. to identify regulated pesticides; however, the CAS No. is not available for most worldwide jurisdictions beyond Europe and North America.

2.3. Sources for Worldwide Pesticide Soil RGVs and Drinking Water MCLs

Pesticide soil RGVs and drinking water MCLs were directly taken from the regulatory jurisdictions and most were obtained from the official government websites, which are the primary sources. Sometimes the primary source was not available when the official documents were too old to have an online version when access was needed for the document, when the official website was under maintenance, and when the jurisdiction needed to be purchased. For these cases, secondary sources such as newspapers, annual reports, research articles, conferences, and government statements were applied to obtain the pesticide standard values. Since many international regulatory jurisdictions were written in foreign languages, the Google translate online tool was used to translate the foreign language documents into English. The reference websites for the worldwide and U.S. pesticide soil RGVs and drinking water MCLs and the pesticide standard values used in this study were provided in supplement materials (Tables S1–S4 and Database). When web addresses and online documents become out of date and inactive, keywords from the document title would help to address the new web location by using web search engines.

Table 1 lists the worldwide nations, regions, territories, and organizations which had provided the pesticide soil or drinking water regulatory jurisdictions, their sources, the numbers of pesticide standard values, and the languages applied. A total of 4590 pesticide soil RGVs were identified by 108 international jurisdictions from 54 United Nation (UN) members, three multi-national organizations, and two non-UN members outside of the U.S. At least 3534 pesticide drinking water MCLs were identified from 130 international jurisdictions from 102 UN members, four multi-national organizations, and two non-UN members outside of the U.S. There were more nations which provided pesticide standard values in drinking water than for residential soil, indicating that more nations focused on pesticide regulations for drinking water. Pesticides RGVs and MCLs were also identified by the U.S. jurisdictions from national organizations, states, cities, U.S. territories, and Autonomous Native American Tribes (see Table 2). There were 14,831 pesticides RGVs identified from 66 U.S. soil regulatory jurisdictions, including 46 of the 50 states, six national organizations, five regions (cities and counties), two U.S. territories, and seven Autonomous Native American Tribes. In addition, a total of 1940 pesticide MCLs were identified by 61 U.S. drinking water jurisdictions, from 48 of the 50 states, three national organizations, and two U.S. territories. Only four states, including North Dakota, South Carolina, South Dakota and Utah, did not provide pesticide soil RGVs, and two states—Georgia and Washington—did not provide pesticide drinking water MCLs.

Table 1.

Worldwide (outside of U.S.) pesticide regulatory guidance values (RGVs) and maximum concentration levels (MCLs) jurisdiction sources for nations, regions, territories, and multi-national organizations.

| No. | Worldwide Jurisdictions | No. of Soil RGVs | No. of Water MCLs | Sources of Pesticide Soil RGVs 1 | Language (Soil RGVs) | Sources of Pesticide Water MCLs 1 | Language (Water MCLs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multinational organizations | |||||||

| 1 | East Africa Community | 17 | 19 | East Africa Community (2011) | English | East African Community (2012) | English |

| 2 | European Union | 14 | UNK 2 | European Union (2010) | English | European Union (1998) | English |

| 3 | Gulf Standardization Organization | --- 3 | 33 | --- | --- | Gulf Standardization Organization (2012) | Arabic & English |

| 4 | World Health Organization | 11 | 36 | World Health Organization (2002) | English | World Health Organization (2011) | English |

| United Nations member states | |||||||

| 1 | Republic of Albania | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Albania Institute for European Environmental Policy (2007) | Albanian |

| 2 | Principality of Andorra | 14 | 25 | Andorra Official Gazette (2010) | Catalan | Andorra Official Gazette (1999) | Catalan |

| 3 | Antigua and Barbuda | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Environmental Solutions Antigua Limited (2008) | English |

| 4 | Argentine Republic | --- | 49 | --- | --- | Argentine Official Gazette (1993) | Spanish |

| 5 | Republic of Armenia | 286 | --- | Armenia Minister of Health (2011) | Armenian | --- | |

| 6 | Commonwealth of Australia | 48 | 152 | Australia National Environmental Protection Council (1999) | English | National Health and Medical Research Council (2013) | English |

| (Australia) Australian Capital Territory | 48 | 152 | Australia National Environmental Protection Council (1999) | English | Australian Capital Territory Ministry of Health (2007) | English | |

| (Australia) Tasmania | 62 | 152 | Tasmania Environmental Protection Authority (2012) | English | Tasmania Department of Health and Human Services (1997) | English | |

| Australia National Environmental Protection Council (1999) | English | ||||||

| (Australia) New South Wales | 18 | 152 | New South Wales Department of Environment and Conservation (2006) | English | Australia Department of Health (2014) | English | |

| (Australia) Northern Australia | 48 | 152 | Australia National Environmental Protection Council (1999) | English | Australia Department of Health (2014) | English | |

| (Australia) Queensland | 48 | 145 | Australia National Environmental Protection Council (1999) | English | Government of Queensland (2014) | English | |

| (Australia) State of Victoria | 67 | --- | Victoria Environmental Protection Authority (2002) | English | --- | --- | |

| Australia National Environmental Protection Council (1999) | English | ||||||

| (Australia) South Australia | 66 | 152 | Australia National Environmental Protection Council (1999) | English | Government of South Australia (2011) | English | |

| South Australia Environment Protection Authority (2006) | English | ||||||

| (Australia) Western Australia | 18 | 152 | Western Australia Department of Environment and Conservation (2010) | English | Australia Department of Health (2014) | English | |

| 7 | Republic of Austria | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Austria Department of Health (2013) | German |

| 8 | Commonwealth of the Bahamas | 123 | 36 | Bahamas Ministry of Works and Transport (2008) | English | The Bahamas Water and Sewerage Corporation (1999) | English |

| 9 | People’s Republic of Bangladesh | 2 | Amio Water Treatment Limited (2010) | English | |||

| 10 | Republic of Belarus | 139 | 16 | Belarus Ministry of Health (2004) | Belarusian | Belarus Ministry of Health (2013) | Russian |

| 11 | Belize | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Belize Agricultural Health Authority (2003) | English |

| 12 | Kingdom of Bhutan | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Codex Alimentarius (2001) | English |

| 13 | Plurinational State of Bolivia | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Bolivia Ministry of Public Works and Services Vice of Basic Services (2004) | Spanish |

| 14 | Republic of Botswana | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Water Utilities Corporation (2000) | English |

| 15 | Federative Republic of Brazil | 8 | 26 | Brazil Ministry of the Environment (2009) | Portuguese | Brazil Ministry of Health (2004) | Portuguese |

| (Brazil) State of San Paolo | 8 | 36 | Environmental Company of Sao Paolo (2005) | Portuguese | Government of State of San Paolo (2008) | Portuguese | |

| 16 | Republic of Bulgaria | 64 | UNK | Bulgaria Ministry of Environment and Water (2008) | Bulgarian | Bulgaria Ministry of Health (2001) | Bulgarian |

| 17 | Kingdom of Cambodia | --- | 19 | --- | --- | Cambodia Ministry of Industry Mines and Energy (2004) | English |

| 18 | Canada | 4 | 25 | Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) (2011) | English | Health Canada (2012) | English |

| (Canada) Alberta | 86 | 25 | Alberta Environment (2010) | English | Alberta Health Services (2013) | English | |

| (Canada) British Columbia | 206 | 25 | --- | --- | British Columbia Ministry of Health (undated) | English | |

| British Columbia Regulations (2013) | English | ||||||

| British Columbia Regulations (2013) | English | ||||||

| (Canada) Province of Manitoba | 4 | --- | Manitoba Conservation (2011), CCME (2011) | English | --- | --- | |

| (Canada) Newfoundland and Labrador | 3 | 25 | Environment and Conservation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (2005) | English | Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (2013) | English | |

| (Canada) Northwest Territories | 4 | 25 | Northwest Territories Department of Environment and Natural Resources (2003) | English | Canada Northwest Territories Municipal and Community Affairs (undated) | English | |

| (Canada) Nova Scotia | 169 | 57 | Nova Scotia Environment (2013) | English | Government of Nova Scotia (2012), Nova Scotia Environment and Labor (undated) | English | |

| (Canada) Nunavut | 6 | 25 | Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut (2009) | English | National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health (2014) | English | |

| (Canada) Ontario | 72 | 24 | Ontario Ministry of the Environment (2011) | English | Canadian Institute for Environmental Law and Policy (2003) | English | |

| (Canada) Prince Edward Island | 3 | 25 | Prince Edward Island Environment, Energy and Forestry (2010) | English | Prince Edward Island Department of Environment, Labor and Justice (2012) | English | |

| (Canada) Quebec | 1 | 34 | Quebec Ministry of Sustainable Development, Environment and Parks (1998) | French | Government of Quebec (2014) | English | |

| (Canada) Saskatchewan | --- | 12 | --- | --- | Saskatchewan Environment (2006) | English | |

| (Canada) Yukon | 5 | 25 | Yukon Regulations (2002) | English | Government of Yukon (2007) | English & French | |

| 19 | Republic of Chile | --- | 8 | --- | --- | Chile Ministry of Public Works (2005) | Spanish |

| 20 | People’s Republic of China | 20 | 17 | Peoples Republic of China (1995) | Chinese | China Department of Health (2007) | Chinese |

| People’s Republic of China Ministry of Environmental Protection (2006) | Chinese | ||||||

| China (Beijing) | 14 | --- | Beijing Municipal Environmental Protection Bureau (2011) | Chinese | --- | --- | |

| 21 | Republic of Colombia | --- | 16 | --- | --- | Colombian Institute for Technical Standards and Certification (1994) | Spanish |

| 22 | Republic of Costa Rica | 8 | 33 | Ministry of Health (2011) | Spanish | Costa Rica Minister of Finance (2005) | Spanish |

| 23 | Republic of Croatia | 15 | UNK | Agricultural University of Zagreb (2008) | Croatian | Croatia Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (2007) | Croatian |

| 24 | Republic of Cuba | --- | 16 | --- | --- | Cuba Government (1997) | Spanish |

| 25 | Republic of Cyprus | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Cyprus Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment (1999) | English |

| 26 | Czech Republic | 11 | UNK | Czech Republic Ministry of the Environment (1994) | English | European Commission (1998) | Czech |

| European Commission (2007) | English | ||||||

| 27 | Kingdom of Denmark | 9 | UNK | Danish Environmental Protection Agency (2010) | Danish | Nature Agency of Denmark (2014) | Danish |

| 28 | Dominican Republic | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Dominican Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance (2005) | Spanish |

| 29 | Republic of Ecuador | 27 | 19 | Ecuador Ministry of the Environment (2004) | Spanish | Ecuadorian Institute of Standards (2011) | Spanish |

| 30 | Arab Republic of Egypt | --- | 33 | --- | --- | World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2006) | English |

| 31 | Republic of Estonia | 12 | UNK | Estonia Ministry of the Environment (2004) | Estonian | Estonia Minister of Social Affairs (2013) | Estonian |

| 32 | Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia | --- | 10 | --- | --- | World Health Organization (2010) | English |

| 33 | Republic of Fiji | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Secretariat of the Pacific Community (2005) | English |

| 34 | Republic of Finland | 12 | UNK | Finland Ministry of the Environment (2007) | Finish | Finland Minister of Social Affairs and Health (2001) | Finish |

| 35 | French Republic | 18 | UNK | European Commission (2007) | English | France Ministry of Ecology, Sustainable Development And Energy (1998) | French |

| 36 | Republic of the Gambia | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Gambia Environmental Quality Standards Board (1999) | English |

| 37 | Georgia | 231 | UNK | Georgia Minister of Environment and Minister of Natural Resources (2006) | Georgian | Georgia Ministry of Justice (2007) | Georgian |

| Minister of Health, labor and social affairs (2001) | Georgian | ||||||

| 38 | Federal Republic of Germany | 8 | UNK | German Federal Ministry of the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (1999) | German | Germany Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection (2001) | German |

| 40 | Republic of Guatemala | --- | 55 | --- | --- | Guatemala Government (1999) | Spanish |

| 39 | Hellenic Republic | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Greece Central Public Health Laboratory (1998) | Greek |

| 41 | Republic of Honduras | --- | 33 | --- | --- | Honduras Department of Health (1995) | Spanish |

| 42 | Republic of Hungary | 68 | UNK | Hungary Ministry of the Environment (2000) | Hungarian | Hungary National Public Health and Medical Officer Service (2001) | Hungarian |

| 43 | Republic of Indonesia | --- | 17 | --- | --- | Indonesia Government (1990) | Indonesian |

| 44 | Republic of Iraq | --- | 3 | --- | --- | Iraq Central Agency for Meteorology and Quality Control (2001) | Arabic & English |

| 45 | Ireland | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Ireland EPA (2007) | English |

| 46 | State of Israel | --- | 7 | --- | --- | Israel Ministry of Health (2000) | Hebrew |

| 47 | Republic of Italy | 13 | 59 | Italy National Institute of Health (2006) | Italian | Navy Medicine (2012) | English |

| UNK | Italy Ministry of Health (2001) | Italian | |||||

| (Italy) Lombardi Region | 9 | --- | Tazzioli (1999) | Italian | --- | --- | |

| (Italy) Piedmont Region | 1 | --- | Tazzioli (1999) | Italian | --- | --- | |

| (Italy) Emili Romana Region | 1 | --- | Tazzioli (1999) | Italian | --- | --- | |

| (Italy) Liguria Region | 1 | --- | Tazzioli (1999) | Italian | --- | --- | |

| 48 | Japan | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Japan Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (2001) | English & Japanese |

| 49 | Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan | --- | 11 | --- | --- | The Jordanian Institute of Standards and Metrology (2001) | English |

| 50 | Republic of Kazakhstan | --- | 3 | --- | --- | Kazakhstan Government (2001) | Russian |

| 51 | Republic of Kiribati | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Secretariat of the Pacific Community (2005) | English |

| 52 | Republic of Korea | --- | 5 | --- | --- | Korea Ministry of Environment (2011) | English |

| 53 | State of Kuwait | --- | 36 | --- | --- | World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2006) | English |

| 54 | Republic of Latvia | 17 | UNK | Latvia Cabinet of Ministers (2005) | Latvian | Latvia Ministry of Health (2004) | Latvian |

| 55 | Lebanese Republic | --- | 4 | --- | --- | World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2006) | English |

| 56 | Principality of Liechtenstein | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Liechtenstein Drinking Water Inspectorate (1999) | English |

| 57 | Republic of Lithuania | 24 | UNK | Lithuania Ministry of the Environment (2008) | Lithuanian | Lithuania Ministry of Health (2003) | Lithuanian |

| 58 | Grand Duchy of Luxembourg | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Luxembourg Collection of Legislation (2002) | French |

| 59 | Malaysia | 194 | 23 | Malaysia Environment Protection Department (2009) | English | Malaysia Ministry of Health (2010) | English |

| 60 | Republic of Malta | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Malta Government (2009) | Maltese |

| 61 | Republic of Mauritius | --- | 10 | --- | --- | Mauritius Government Gazette (1996) | English |

| 62 | United Mexican States | --- | 18 | --- | --- | Government of Mexico (1994) | Spanish |

| 63 | Republic of Moldova | 166 | --- | Moldova Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources (2004) | Romanian | --- | --- |

| 64 | Mongolia | --- | 5 | --- | --- | Government of Mongolia (2005) | Mongolian |

| 65 | Kingdom of Morocco | --- | 1 | --- | --- | World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2006) | English |

| 66 | Republic of Nauru | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Secretariat of the Pacific Community (2005) | English |

| 67 | Kingdom of the Netherlands | 61 | UNK | Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (2006) | English | Government of Netherlands (2014) | Dutch |

| Netherlands Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation (2006) | English | ||||||

| Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (2009) | English | ||||||

| 68 | New Zealand | 344 | 55 | New Zealand Ministry of the Environment (2012) | English | New Zealand Ministry of Health (2008) | English |

| New Zealand Ministry of the Environment | English | ||||||

| New Zealand Ministry of the Environment (1997) | English | ||||||

| New Zealand Ministry of the Environment (2006) | English | ||||||

| New Zealand Ministry of the Environment (2011) | English | ||||||

| New Zealand Ministry of the Environment | English | ||||||

| (New Zealand) Auckland City Council | 9 | --- | Cavanagh (2006) | English | --- | --- | |

| (New Zealand) Auckland Regional Council | 5 | --- | Cavanagh (2006) | English | --- | --- | |

| (New Zealand) Bay of Plenty | 4 | --- | Cavanagh (2006) | English | --- | --- | |

| (New Zealand) Hastings District Council | 3 | --- | Cavanagh (2006) | English | --- | --- | |

| (New Zealand) Tasmasn District Council | 10 | --- | Cavanagh (2006) | English | --- | --- | |

| (New Zealand) Waikato Region | 8 | --- | Cavanagh (2006) | English | --- | --- | |

| 69 | Republic of Nicaragua | --- | 35 | --- | --- | Nicaragua Ministry of Health (1994) | Spanish |

| 70 | Federal Republic of Nigeria | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Standards Organization of Nigeria (2007) | English |

| 71 | Kingdom of Norway | 3 | UNK | Norwegian Pollution Control Authority (1999) | English | Norway Ministry of Health and Care Services (2001) | Norwegian |

| 72 | Islamic Republic of Pakistan | --- | 19 | --- | --- | Pakistan Standards and Quality Control Authority (Undated) | English |

| 73 | Republic of Palau | --- | 6 | --- | --- | Environmental Quality Protection Board (Undated) | English |

| 74 | Republic of Panama | 20 | --- | Panama Ministry of Economy and Finance (2009) | Spanish | --- | --- |

| 75 | Republic of Peru | 4 | 45 | Peru Ministry of Environment (2013) | Spanish | Peru Ministry of Health (2011) | Spanish |

| 76 | Republic of the Philippines | --- | 17 | --- | --- | Philippines Department of Health (2007) | English |

| 77 | Republic of Poland | 14 | UNK | Poland Minister of the Environment (2002) | Polish | Poland Ministry of Health (2007) | Polish |

| 78 | Portuguese Republic | 15 | UNK | Ontario Ministry of Environment and Energy (1997) | Portuguese and English | Portugal Ministry of Environment, Planning and Regional Development (2007) | Portuguese |

| 79 | State of Qatar | 4 | 33 | Qatar Ministry of Environment (2007) | Arabic | The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Standardization (2012) | Arabic & English |

| 80 | Russian Federation | 146 | 106 | Russian State Construction Code (1997) | Russian | Russian Ministry of Health (1998, 1999, 2002, 2007) | Russian |

| Russian Ministry Of Environment and Natural Resources (1993) | Russian | ||||||

| (Russia) City of Moscow | 1 | --- | Moscow Government (2004) | Russian | --- | --- | |

| (Russia) Republic of Tatarstan | 137 | --- | Republic of Tatarstan Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (2002) | Russian | --- | --- | |

| 81 | Republic of Rwanda | --- | 19 | --- | --- | Rwanda Standards Board (2013) | English |

| 82 | Saint Lucia | --- | 40 | --- | --- | Caricom Regional Organization for Standards and Quality (undated) | English |

| 83 | Republic of Serbia | 56 | 28 | Serbia Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning (1994) | English | Serbia Official Gazette (1999) | English |

| 84 | Republic of Singapore | 46 | 39 | Singapore National Environmental Agency (2010) | English | Government of Singapore (2008) | English |

| 85 | Slovak Republic | 5 | UNK | Slovakia Ministry of Agriculture (2004) | Slovak | Council Regulation Government of the Slovak Republic (2010) | Slovak |

| 86 | Republic of Slovenia | 45 | UNK | Slovenia Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning (1996) | Slovenian | Slovenia Ministry of Health (2004) | Slovenian |

| 87 | Republic of South Africa | 10 | 1 | South Africa Department of Environmental Affairs (2010) | English | South Africa Department of Water and Sanitation (2005) | English |

| 88 | Kingdom of Spain | 14 | UNK | Spain Ministry of the Presidency (2005) | Spanish | Government of Spain (2003) | Spanish |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Andalusia | 19 | --- | Andalusia Ministry of Environment (2006) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Aragon | 14 | --- | Government of Aragon (2005) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Principality of Asturias | 14 | --- | The Government of the Principality of Asturias (2005) | Asturianu | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community Balearic Islands | 14 | --- | Ministry of Agriculture, Environment and Territory of Balearic Islands (2013) | Catalan | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Basque Country | 17 | --- | Basque Government, Department of Environment, Planning, Agriculture and Fisherie (2005) | Basque | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Canary Islands | 14 | --- | Government of Canary Islands (2007) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Cantabria | 14 | --- | Government of Cantabria (2006) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Castile and Leon | 14 | --- | Government of Castile and Leon | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Castile La Mancha | 14 | --- | Jiménez Ballesta et al. (2010) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Catalonia | 23 | --- | Waste Agency of Catalonia (2005) | Catalan | --- | --- | |

| Andalusia Ministry of Environment (2006) | Spanish | ||||||

| (Spain) Autonomous City of Ceuta | 14 | --- | Official Portal of Ceuta (2013) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Extremadura | 14 | --- | Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (2010) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Galicia | 23 | --- | Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of Galicia (2009) | Galician | --- | --- | |

| Andalusia Ministry of Environment (2006) | Spanish | ||||||

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of La Rioja | 14 | --- | Government of La Rioja (2007) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Madrid | 14 | --- | Spain Ministry of the Presidency (2005) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous City of Melilla | 14 | --- | Ministry of Environment of the Autonomous City of Melilla (undated) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Region of Murcia | 14 | --- | Government of Region of Murcia (2011) | Spanish | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Navarra | 14 | --- | Department of Rural Development, Environment and Local Government (undated) | Basque | --- | --- | |

| (Spain) Autonomous Community of Valencia | 14 | --- | Generalist at Valencian Regional Ministry of Infrastructure, Planning and the Environment (2007) | Catalan | --- | --- | |

| 89 | Republic of the Sudan | --- | 36 | --- | --- | World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2006) | English |

| 90 | Kingdom of Sweden | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Sweden Nutrition and Food Agency (2001) | Swedish |

| 91 | Swiss Confederation | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Switzerland Department of Consumer and Veterinary (2014) | French |

| 92 | Syrian Arab Republic | --- | 12 | --- | --- | World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2006) | English |

| 93 | United Republic of Tanzania | 17 | 1 | Tanzanian Bureau of Standards (2007) | English | Tanzania Bureau of Standards (2009) | English |

| 94 | Kingdom of Thailand | 9 | 1 | Thailand Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (2004) | English | Thailand Ministry of Health (2001) | Thai |

| 95 | Kingdom of Tonga | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Secretariat of the Pacific Community (2005) | English |

| 96 | Republic of Turkey | 1 | --- | Turkey Ministry of Environment and Forestry (2001) | Turkish | --- | --- |

| 97 | Republic of Tunisia | --- | 1 | --- | --- | Global Water and Wastewater Quality Regulations (2012) | English |

| 98 | Tuvalu | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Secretariat of the Pacific Community (2005) | English |

| 99 | Republic of Uganda | --- | 34 | --- | --- | Uganda Ministry of Tourism, Trade and Industry (2008) | English |

| 100 | Ukraine | 286 | UNK | Ministry of Health of Ukraine (2001) | Ukrainian | Ukraine Water Health (Undated) | Russian |

| 101 | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | --- | UNK | --- | --- | United Kingdom Drinking Water Inspectorate (2000) | English |

| (United Kingdom) Northern Ireland | --- | UNK | --- | --- | Statutory Rules of Northern Ireland (2007) | English | |

| (United Kingdom) Anglian Water Services | 1 | --- | Anglian Water Services Ltd. (2010) | English | --- | --- | |

| (United Kingdom) White Young Green Environmental Ltd | 2 | --- | White Young Green Environmental Ltd. (2008) | English | --- | --- | |

| (United Kingdom) Environmental Industries Commission | 36 | --- | Environmental Industries Commission (2010) | --- | --- | ||

| 102 | Eastern Republic of Uruguay | --- | 41 | --- | --- | Uruguay Administration of Sanitary Works (2006) | Spanish |

| 103 | Republic of Uzbekistan | 104 | 2 | Head of State health officer of the Republic of Uzbekistan (2005) | Russian | Uzbekistan Ministry of Health (2006) | Russian |

| 104 | Republic of Vanuatu | --- | 36 | --- | --- | Secretariat of the Pacific Community (2005) | English |

| --- | UNK | --- | --- | Secretariat of the Pacific Community (2005) | English | ||

| 105 | Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela | --- | 16 | --- | --- | Venezuela Ministry of Health And Welfare (1998) | Spanish |

| 106 | Socialist Republic of Vietnam | 60 | 36 | Republic of Vietnam (2008) | Vietnamese | Viet Nam Ministry of Health (2002) | Vietnamese |

| Republic of Vietnam (1995) | Vietnamese | ||||||

| Jurisdictions other than United Nations member states | |||||||

| 1 | Palestine | --- | 20 | --- | --- | Palestinian Water Authority (1997) | Arabic |

| 2 | Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) | 197 | 6 | The State Standard of the USSR (1983) | Russian | Medical Officer of the USSR (1981), State Sanitary of the USSR (1987) | Russian |

| State Medical Officer of the USSR (1982) | Russian | ||||||

| the USSR Ministry (1991) | Russian | ||||||

| Ministry of Health of the USSR (1980) | Russian | ||||||

1 The reference websites of the worldwide pesticide soil RGVs and drinking water MCLs were provided in supplement materials. 2 UNK—The European Union and some nations promulgated pesticide standard values for distinct classes of pesticides, but as the members of these classes are not specified individually, the total number of standard values is unknown. 3 Notation --- indicates that the nations, regions, or organizations did not provide any pesticide standard values.

Table 2.

U.S. pesticide RGVs and MCLs jurisdiction sources for state, regions, U.S. territories, and national organizations.

| No. | U.S. Jurisdictions | No. of Soil RGVs | No. of Water MCLs | Sources of U.S. Pesticide Soil RGVs 1 | Sources of U.S. Pesticide Water MCLs 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. national organization jurisdictions | |||||

| 1 | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency | 516 | 24 | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2009) |

| 2 | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | 39 | --- 2 | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Response and Restoration (2008) | --- |

| 3 | National Aeronautics and Space Administration | 20 | --- | Boeing Company, National Aeronautics and Space Administration and Department of Energy (2010) | --- |

| 4 | Department of Energy | 20 | --- | Boeing Company, National Aeronautics and Space Administration and Department of Energy (2010) | --- |

| 5 | Food and Drug Administration | --- | 24 | --- | Food and Drug Administration (2013) |

| 6 | U.S. Army Public Health Command | --- | 520 | U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine (2013) | U.S. Army Public Health Command (2013) |

| U.S. Army | 259 | --- | --- | --- | |

| 7 | Agency of Toxic Substance and Disease Registry | 26 | --- | Agency of Toxic Substance and Disease Registry (2008, 2009a, f, 2010c, 2013) | --- |

| U.S. state and regional jurisdictions | |||||

| 1 | State of Alabama | 59 | 24 | Alabama Department of Environmental Management (2008) | Alabama Department of Environmental Management (undated *) |

| 2 | State of Alaska | 87 | 27 | Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (2012) | Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (2008) |

| 3 | State of Arizona | 523 | 24 | Arizona Administrative Code (2009) | Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (2008) |

| Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (2002) | |||||

| 4 | State of Arkansas | 519 | 24 | Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality (2008) | Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality (2013) |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 5 | State of California | 16 | 35 | California Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (2010) | California Office of Environment Health Hazard Assessment (2010) |

| 2 | California Department of Public Health (2010) | ||||

| 15 | California Department of Health Services (2010) | ||||

| 27 | California Department of Health Services (2014) | ||||

| (California) City of Oakland | 4 | --- | City of Oakland Public Works Agency (2000) | ||

| (California) San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board | 40 | --- | San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board (2013) | ||

| 6 | State of Colorado | 551 | 28 | Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (2011) | Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (2014) |

| 7 | State of Connecticut | 14 | 24 | Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (2013) | Connecticut Department of energy and environmental protection (2013) |

| 7 | Connecticut Department of energy and environmental protection (2014) | ||||

| 8 | State of Delaware | 413 | 24 | Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (1999, 2013) | Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (undated) |

| 9 | State of Florida | 143 | 85 | Florida Department of Environmental Protection (2005) | Florida Department of Health (2014) |

| (Florida) Miami-Dade County | 142 | --- | Code of Miami-Dade County (2008) | --- | |

| 10 | State of Georgia | 151 | --- | Georgia Department of Natural Resources (1993) | --- |

| 11 | State of Hawaii | 30 | 24 | Hawaii Department of Health (2011) | Hawaii Department of Health (2009) |

| 12 | State of Idaho | 47 | 24 | Idaho Department of Environmental Quality (2004) | Idaho Department of Environmental Quality (2014) |

| 13 | State of Illinois | 68 | 13 | Illinois Administrative Code (2010) | Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (undated) |

| Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (2011) | |||||

| 14 | State of Indiana | 215 | 24 | Indiana Department of Environmental Management (2013) | Indiana Department of Environmental Management (undated) |

| 24 | Indiana Department of Environmental Management (1996) | ||||

| 15 | State of Iowa | 94 | 24 | Iowa Department of Natural Resources (2013) | Iowa Department of Nature Resources (2012) |

| 16 | State of Kansas | 62 | 27 | Kansas Department of Health and Environment (2010) | Kansas Department of Health and Environment (2004) |

| 17 | Commonwealth of Kentucky | 516 | 24 | Kentucky Energy and Environmental Cabinet (2011) | Kentucky Department of environmental protection (2010) |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 18 | State of Louisiana | 22 | 24 | Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (2003) | Louisiana Department of Health and Hospital (undated) |

| 19 | State of Maine | 545 | 24 | Maine Department of Environmental Protection (2011, 2013) | Government of Maine (undated) |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 20 | State of Maryland | 33 | 24 | Maryland Department of the Environment (2008) | Maryland Department of Environment (undated) |

| 21 | Commonwealth of Massachusetts | 119 | 24 | Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (2014) | Massachusetts Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Energy and Environmental Affairs (2012) |

| 22 | State of Michigan | 62 | 24 | Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (2012) | Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (2014) |

| 23 | State of Minnesota | 132 | 27 | Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (2009) | Minnesota Department of Health (2011) |

| 24 | State of Mississippi | 113 | 24 | Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality (2002) | Mississippi Department of Health (2013) |

| 25 | State of Missouri | 309 | 24 | Missouri Department of Natural Resources (2010) | Missouri Department of Natural Resources (1996) |

| 26 | State of Montana | 516 | 24 | Montana Department of Environmental Quality (2012) | Montana Department of Environmental Quality (2004) |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 27 | State of Nebraska | 215 | 24 | Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality (2012) | Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services (2012) |

| 28 | State of Nevada | 386 | 24 | Nevada Division of Environmental Protection (2009, 2013) | Nevada Division of Environmental Protection (2013) |

| 29 | State of New Hampshire | 87 | 27 | New Hampshire Code of Administrative Rules (2008) | New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services (2013) |

| 30 | State of New Jersey | 51 | 24 | New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (1999, 2012) | New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (2011) |

| 3 | New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (2009) | ||||

| 31 | State of New Mexico | 511 | 24 | New Mexico Environment Department (2012) | New Mexico Environment Department (2003) |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 32 | State of New York | 69 | 21 | New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (2006, 2010) | New York Department of Health (2011) |

| (New York) New York City | 63 | --- | New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (2006) | --- | |

| (New York) Suffolk County | 3 | --- | Suffolk County Department of Health Services (2011) | --- | |

| 33 | State of North Carolina | 304 | 24 | North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources (2005, 2012, 2013) | North Carolina Division of Water Resources (2011) |

| 34 | State of North Dakota | 24 | North Dakota Department of Health (2005) | ||

| 35 | State of Ohio | 437 | 24 | Ohio Administrative Code (2009) | Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (UNDATED) |

| Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (2005, UNDATED) | |||||

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 36 | State of Oklahoma | 516 | 24 | Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (2013) | Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (2012) |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 37 | State of Oregon | 608 | 24 | Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (2010, 2012) | Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (2000) |

| 20 | Oregon Public Health (2012) | ||||

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 38 | Commonwealth of Pennsylvania | 134 | 24 | Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (2014) | Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (2006) |

| 39 | Rhode Island | 7 | 24 | Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (2011) | Rhode Island Department of Health (2011) |

| 40 | State of South Carolina | --- | 24 | --- | South Carolina Department of Health and Environment (2009) |

| 41 | State of South Dakota | --- | 27 | --- | South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources (undated) |

| 42 | State of Tennessee | 516 | 24 | Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (2001) | Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (undated) |

| 43 | State of Texas | 1140 | 24 | Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (2003, 2006a, b, 2012) | Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (2013) |

| 44 | State of Utah | --- | 24 | --- | Utah Department of Environmental Quality (2014) |

| 45 | State of Vermont | 754 | 24 | Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation (2012) | Vermont Agency of Natural Resources (2010) |

| 2 | Vermont Department of Health (2002) | ||||

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 46 | Commonwealth of Virginia | 347 | 24 | Virginia Department of Environmental Control (UNDATED) | Virginia Department of Health (2014) |

| 47 | State of Washington | 252 | --- | Washington Department of Ecology (2007, 2014) | --- |

| 48 | State of West Virginia | 326 | 24 | West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (2009a, b) | Business and Legal Resources (2014) |

| 49 | State of Wisconsin | 237 | 24 | Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (2013) | Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (2013) |

| 50 | State of Wyoming | 25 | 38 | Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality (2013) | Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality (2013) |

| U.S. territories | |||||

| 1 | Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands | 128 | 23 | Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Environmental Quality (2012) | CNMI Division of Environmental Quality (2005) |

| 2 | Unincorporated Territory of Guam | 128 | 6 | Guam Environmental Protection Agency (2012) | Guam Environmental Protection Agency (1997) |

| Autonomous native American jurisdictions | |||||

| 1 | The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation | 1 | --- | Colville Confederated Tribes (2008) | --- |

| 2 | Confederated Tribes of the Coos-Lower Umpqua-Siuslaw Indians | 608 | --- | Confederated Tribes of the Coos-Lower Umpqua-Siuslaw Indians (2010) | --- |

| Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (2010, 2012a, b, 2014) | |||||

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2013) | |||||

| 3 | Hoppa Valley Tribe | 239 | --- | Hoppa Valley Tribe (2008) | --- |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region IX (2004) | |||||

| 4 | Metlakatla Indian Community | 2 | --- | Metlakatla Indian Community (2011) | --- |

| 5 | Nez Perce Tribe | 41 | --- | Nez Perce Tribe (2009) | --- |

| 6 | Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe | 252 | --- | Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe (2010) | --- |

| Washington Department of Ecology (2001, 2014) | |||||

| 7 | Shoshone-Bannock Tribes | 20 | --- | Shoshone-Bannock Tribes (2010) | --- |

1 The reference websites of the U.S. pesticide soil RGVs and drinking water MCLs were provided in supplement materials. 2 Notation --- indicates that the nations, regions, or organizations did not provide any pesticide standard values. * Undated—The date on which jurisdictions were generated, revised, drafted, or published is unavailable.

2.4. Sources for Worldwide Pesticide Agricultural Commodity MRLs

Pesticide agricultural commodity MRLs of worldwide nations were collected by the global MRL database (2014) [16], which included at least 90 nations and multi-national organizations (see Table 3). Since hundreds of agricultural commodities and pesticides were regulated and collected in this database, only the currently most widely used pesticides and the most consumed agricultural commodities were used in this research to compute the IED. The most widely used pesticides and consumed foods were selected based on worldwide pesticide usage and the consumption of foods, which was investigated for the nations where agricultural plays a significant role, such as China [17,18], India [19], the Philippines [20], Germany [21], the United Kingdom [22], Canada [23,24], the U.S. [25,26,27], Mexico [28], Costa Rica [29], Brazil [30,31], New Zealand [32], Australia [33,34], and South Africa [35]. The 14 current most widely used pesticides selected in this research review were 2,4-D, Aldicarb, Atrazine, Chlorothalonil, Chlorpyriphos, Diazinon, Dicamba, Diuron, Glyphosate, Malathion, Mancozeb, MCPA, Metolachlor, and Trifluralin. The most consumed agricultural commodities selected in this study were classified into four groups: grain crops (corn, wheat, and rice), vegetable crops (tomato, onion, and potato), fruit crops (apple, bananas, grape, and orange), and drinks (coffee bean, and tea leaves). Although pesticides can be transported and accumulate into meat and dairy products such as beef and fish, agricultural commodities are often exposed to pesticides directly, due to application methods such as spraying. The amount of pesticide accumulated in livestock always depends on the living environment, feeding stuff, and the metabolism of the animals. Compared to the pesticide exposure from the meat consumption, the pesticide exposure risk from agricultural commodities is much higher due to its broader application. Thus, pesticide exposure from the consumption of meat and dairy products will not be discussed in this study; however, marginal safety factors should be accounted for to allow additional exposures.

Table 3.

Estimated intake rates for the most consumed agricultural commodities

| Crop Type | Agricultural Commodity | Intake Rate Estimated (kg/day) |

|---|---|---|

| Fruit crops | Apple | 0.019 |

| Banana | 0.032 | |

| Grape | 0.009 | |

| Orange | 0.028 | |

| Vegetable crops | Potato | 0.042 |

| Tomato | 0.021 | |

| Onion | 0.023 | |

| Grain crops | Rice | 0.156 |

| Wheat | 0.223 | |

| Maize | 0.042 | |

| Drink crops | Tea | 0.001 |

| Coffee | 0.012 |

2.5. Sources for Pesticide Residential Air MCLs

Few jurisdictions in the world had regulated pesticide residential air MCLs; only the U.S. [36] regulated and derived the pesticide air MCLs systematically. Cancer and non-cancer human health risk models were developed by the U.S Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), and the MCLs for 43 volatile and semi-volatile pesticides were promulgated. It is necessary to regulate pesticide air MCLs as the human health risks are raised by inhalation, skin contact, and even eye contact for pesticide-contaminated air, especially for farmers and workers who work in forests and the agricultural field. The regulation of pesticides in the air can also protect the ecosystem, wildlife, and livestock. Because of the lack of information available for worldwide pesticide air MCLs, regulatory pesticide standard values for residential air are omitted in this study.

3. Methods

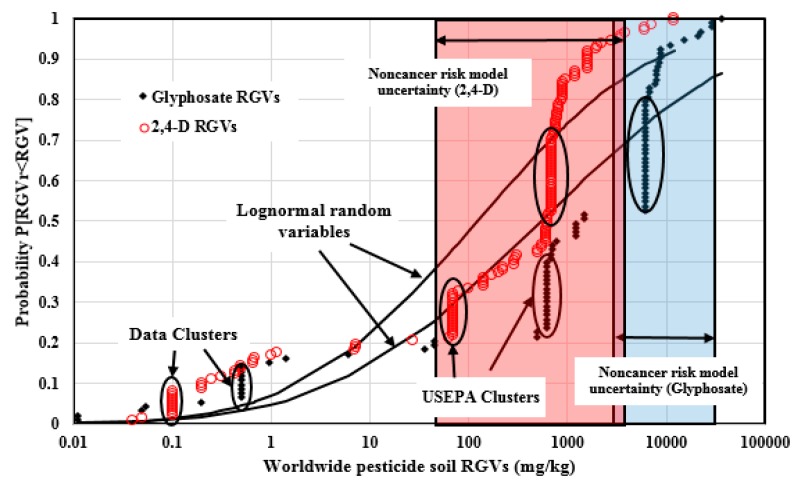

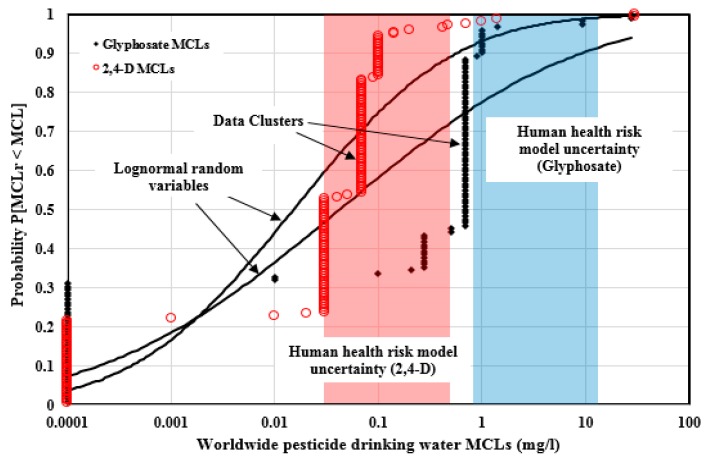

3.1. Statistical Analysis of Pesticide Standard Values

Since most data sets for pesticide standard values resemble a log-transformed random distribution [37,38,39,40,41], the cumulative distribution function was applied to plot the pesticide standard values and to compare it with the cumulative distribution of a log-normal random variable with identical statistics, arithmetic, mean, and standard deviations. The cumulative distribution function was used to illustrate how worldwide pesticide standard values dispersed over the span of values and the ranking of the standard values for each jurisdiction. The empirical cumulative distributions generated from pesticide standard value sets were generated as follows,

| (1) |

where Xr is a random value for a pesticide RGV, MCL, IED, IMDL, or the number of pesticide standard values which a jurisdiction had provided, Xi is the known value for the same pesticide, and ni is the integer rank of Xi in the N known values.

To examine if the degree of the empirical distribution resembled the log-normal random distribution of a Pearson (r) correlation, the analysis was conducted as follows,

| (2) |

where E(Xi) is the probability computed from the empirical distribution, and F(Xi) is the probability calculated for the log-normal cumulative distribution.

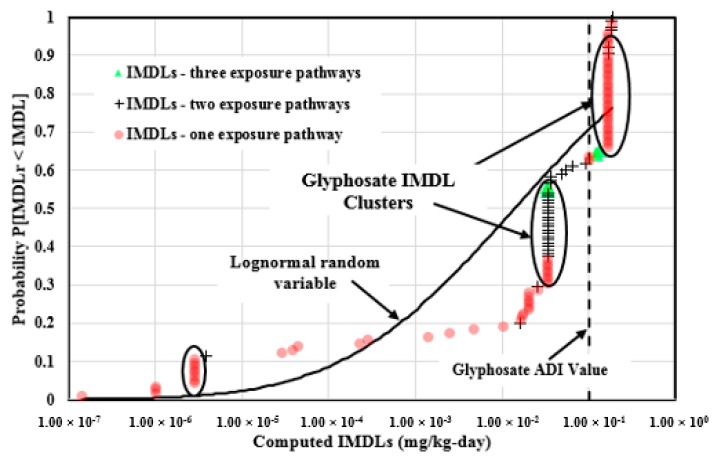

Since some jurisdictions shared the same standard value for a certain pesticide, non-random values always appeared in empirical distributions. A data value cluster was introduced in this study and defined as a data interval (Xi − Xi+Y), containing Y values which did not occur randomly. The probability (Pc) of a randomly occurring data value cluster was quantified by the binomial probability function as follows,

| (3) |

where F(Xi) and F(Xi+Y) were computed from the log-normal cumulative distribution. A probability of less than 0.001 indicated that the data value cluster did not occur randomly.

3.2. Human Health Risk Models

Many regulatory jurisdictions developed standard values for non-genotoxic pesticides, “thresholded toxicants” [42], or “systemic toxicants” [43] based on the acceptable daily intake (ADI), tolerable daily intake (TDI), or reference dose (RfD) [43]. The standard values are defined as the level of toxicant exposure on a daily or weekly basis without adverse health effects or an appreciable health risk over a lifetime. The ADI or TDI was usually converted from the no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL), or the lowest observed effect level (LOEL) by laboratory animal experiments by applying an uncertainty factor which allows for interspecies differences and human variability, expressed as follows,

| (4) |

where UF is the uncertainty factor and usually applies to a 100-fold increase [42].

Based on the toxicology data, the pesticide soil RGVs should be developed based on exposure scenarios. To evaluate if the pesticide soil RGVs are conservative enough to protect human health, human health cancer and non-cancer risk models (Equations (5)–(12)) developed by the USEPA [36] were applied in this research to compute cancer and non-cancer risk uncertainty bounds. The USEPA models considered all pesticide soil exposure scenarios, such as soil ingestion, soil dust inhalation, and soil dermal contact. There is an uncertainty when using the USEPA models to examine soil RGVs. This does not mean that the USEPA models are universal; every jurisdiction can develop and conduct an RGV risk assessment and evaluation based on their situations. The USEPA summarized the toxicity and chemical-specific information of pesticides, which included the chronic oral slope factor (CSFo) (kg-mg/day), the fraction of contaminant absorbed in gastrointestinal tract (GIABS) (unitless), the fraction of contaminant absorbed dermally from soil (ABSd) (unitless), the chronic inhalation unit risk (IUR) (m3/ug), the volatilization factor (VFs) (m3/kg), the chronic oral reference dose (RfDo) (mg/kg-day), and the chronic inhalation reference concentration (RfC) (mg/m3) [36]. The range of the exposure coefficients [44] applied by the U.S. states were defined in the following equations.

The pesticide soil RGV (mg/kg) equation derived by cancer risk equations was expressed as follows,

| (5) |

where the RSL (mg/kg) is the reginal screen level derived by the cancer risk equations of soil ingestion (Equation (6)), soil dermal contact (Equation (7)), and soil dust inhalation (Equation (8)).

| (6) |

TR—Target risk (1 × 10−6 unit less)

AT—Averaging time (365 days/year)

LT—Lifetime (70 years) (70, 75)

EF—Exposure frequency (350 days/year) (143, 365)

- IFSadj—Resident soil ingestion rate (114 mg-year/kg-day) (87, 127)

(7) - DFSadj—Resident soil dermal contact factor (360.8 mg-year/kg-day), (253, 1257)

(8) PEFw—Particulate emission factor (1.4 × 109 m3/kg), (7.8 × 107–6.6 × 109)

ED—Exposure duration (30 years)

ET—Exposure time (24 h/day), (2, 24)

- The pesticide soil RGV (mg/kg) non-cancer risk equations were expressed as follows,

(9) (10) THQ—Target hazard quotient (1.0 unit less)

EDc—Exposure duration for child (6 year), (5, 7)

HWc—Human weight for child (15 kg), (15, 17)

- IRS—Soil ingestion rate for child (200 mg/day), (100, 200)

(11) SAc—Soil surface area for child (2800 cm2), (1750, 2960)

- AFc—Soil adhesion factor for child (0.2 mg/cm2), (0.2, 1.0)

(12)

Pesticide drinking water MCLs and human health uncertainty risk bounds were based on the exposure scenario of ingestion. The MCL uncertainty risk bounds depend on the variation of the parameters in Equation (13),

| (13) |

where HW is human body weight (kg), which is referred to as an average adult human weight in many jurisdictions. Some jurisdictions, such as the Australian Government [45], applied 70 kg and others, such as WHO [46], used 60 kg. PF is a proportion factor which quantifies the portion of the total pesticide exposure that is allocated to the drinking water ingestion pathway, which usually ranges from 0.1 to 1.0 [46]. V is the daily drinking water intake rate (L/day), and for most worldwide jurisdictions, 2.0 L/day was used, while for some nations with a cold climate, 1.5 L/day was applied [47].

3.3. Pesticide Agricultural Commodity Implied Exposure Dose (IED)

Pesticide IED was introduced to compute the implied pesticide mass burden from the most consumed agricultural commodities, and was compared to the ADI value of the same pesticide. The agricultural food intake rates were estimated in Equation (14) by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) [48] annual food consumption database. It should be noticed that agricultural commodity consumptions vary by season, geology, culture, personal habit, economic status and crop availability. The application of the USDA is one of the methods to estimate consumption rates. Table 3 lists the estimated agricultural food intake rate.

| (14) |

where FIRj is the estimated intake rate of the agricultural commodity j, Mj is the total mass of agricultural commodity j consumed annually in the U.S. (kg/year), and P is the U.S. population (318.9 million for 2014).

The IED for the most widely used pesticides was expressed as follows,

| (15) |

where the IEDi is the implied exposure dose computed for the pesticides i (mg/kg-day), HW is the average adult human weight (kg), and EF is the exposure factor (unit less). The calculated results in this study were based on an average adult weight of 70 kg and an EF of 1.0 [49].

3.4. Implied Maximum Dose Limit

Since human exposure to pesticides always occurs in different exposure pathways simultaneously, it is necessary to develop pesticide standard values comprehensively by considering all possible human exposure scenarios. The IMDL was applied to examine the pesticide standard values in major exposure pathways by computing the implied maximum pesticide mass burden from all major exposures; this was then compared with the ADI value of the same pesticide. The IMDL could be an indicator to assess whether the pesticide standard values were developed comprehensively and conservatively enough to protect human health in all major exposure scenarios. The IMDL was developed based on human exposure models in the following equations. Since there is little information about the worldwide pesticide air standards, the pesticide exposure from the residential air was omitted.

For drinking water:

| (16) |

For residential soil:

| (17) |

For agricultural commodities:

| (18) |

| (19) |

where IDL is the implied dose limit (mg/kg-day) computed from drinking water, soil, and agricultural commodities. For the IDLsoil, since the soil dust inhalation pathway contribution is extremely low compared to soil ingestion and soil dermal contact exposure, the soil inhalation exposure was omitted for the IDLsoil calculation. If more than one PSV for a certain pesticide was regulated by a nation in one major exposure, different IMDLs were calculated by combining different IDLs with others.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Numbers of RGVs and MCLs in Worldwide Jurisdictions

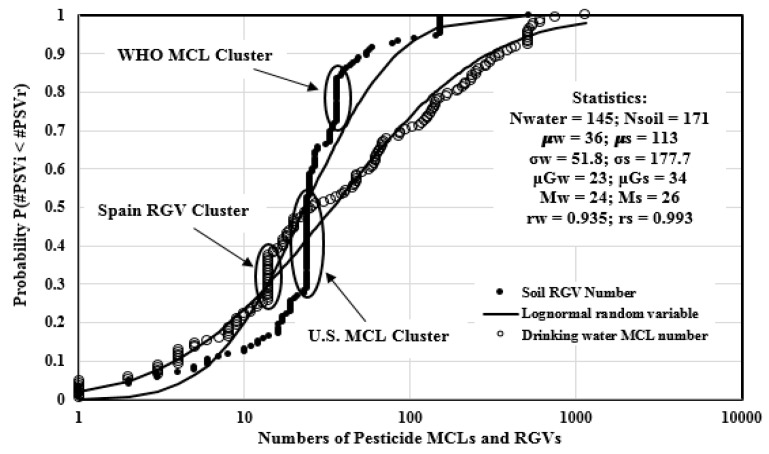

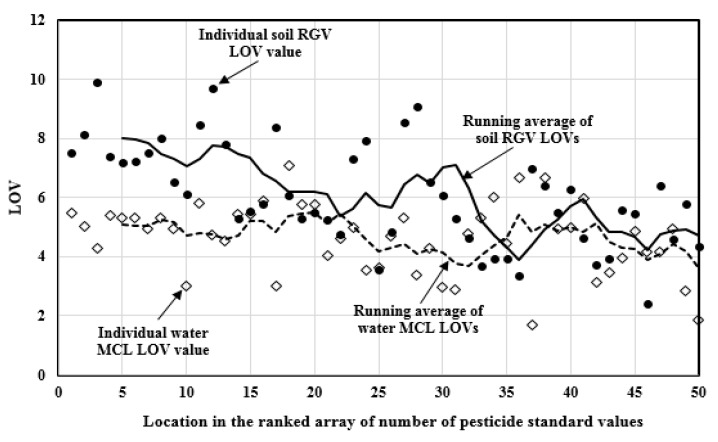

Figure 1 illustrated the distributions of the numbers of pesticide soil RGVs and drinking water MCLs regulated by worldwide jurisdictions. There are 145 worldwide soil jurisdictions and 171 drinking water jurisdictions which had provided the pesticide standard values. For worldwide soil jurisdictions, the numbers of RGVs span 3.06 orders of magnitude (1, 1140), and are well dispersed with the Pearson coefficient of 0.993. The state of Texas had provided the maximum number of soil RGVs, which is 1140. Jurisdictions from Quebec (Canada), three Italian regions, Moscow (Russia), Turkey, Anglian Water Services (United Kingdom), and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation (U.S.) only regulated one soil pesticide RGV. There is one soil RGV number data cluster at 14. The data cluster is made up of 21 jurisdictions from the European Union, Andorra, China (Beijing), Poland, the state of Connecticut, and 16 Span jurisdictions. The arithmetic mean of the soil RGV numbers is 113, and only 50 (29.2% of the total) jurisdictions had RGV numbers above this value, because the arithmetic mean is heavily skewed by some large values such as 1140 (Texas) at the high end of the distribution. The median and geometric mean of the RGV numbers are 26 and 34, respectively, which are better measures of the central tendency of the distribution. For drinking water jurisdictions, the numbers of the MCLs span 2.72 orders of magnitude (1520), and are well dispersed with the Pearson coefficient of 0.935. Since some nations, such as European nations, applied drinking water MCLs as individual and total standards, the number of the MCLs regulated in these nations is not clear (see Table 1 for details) and the information regarding MCL numbers from these jurisdictions was not shown in Figure 1. The U.S. Army Public Health Command had provided the maximum number of drinking water MCLs, which is 520. Jurisdictions from Morocco, South Africa, Tanzania, Thailand, and Tunisia only regulated one pesticide MCL. There are two drinking water MCL numbers data clusters. The cluster at 24 is made up of 35 values from the province of Ontario (Canada) and 34 U.S. related jurisdictions. The cluster at 36 is made up of 17 values from the WHO, Albania, Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Belize, Bhutan, State of San Paolo (Brazil), Fiji, Japan, Kiribati, Kuwait, Nauru, Sudan, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, and Vietnam. The arithmetic mean of the MCL numbers is 36, and this value is larger than the median and geometric mean, which are 24 and 23, respectively, because the arithmetic mean is skewed by some large values such as 520 (U.S. Army Public Health Command). In general, worldwide jurisdictions had regulated more pesticide soil RGVs than drinking water MCLs, because usually pesticides are directly applied to agricultural land, forest, and home gardens, which make the pesticides accumulate in the surface soil first. However, there are more nations regulating pesticides standard values in drinking water (102 nations) than in soil (54 nations), which indicates that more nations focus on the regulation of pesticides in drinking water.

Figure 1.

Empirical distributions of the number of worldwide regulatory guidance values (RGVs) and maximum concentration levels (MCLs) compared to the theoretical distribution of a lognormal random variables.

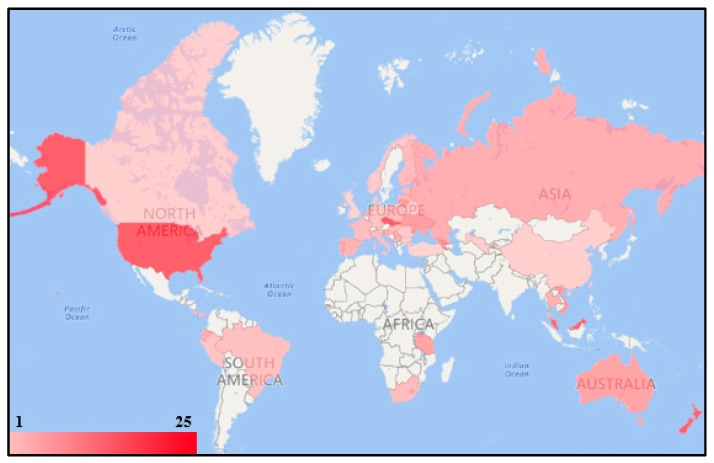

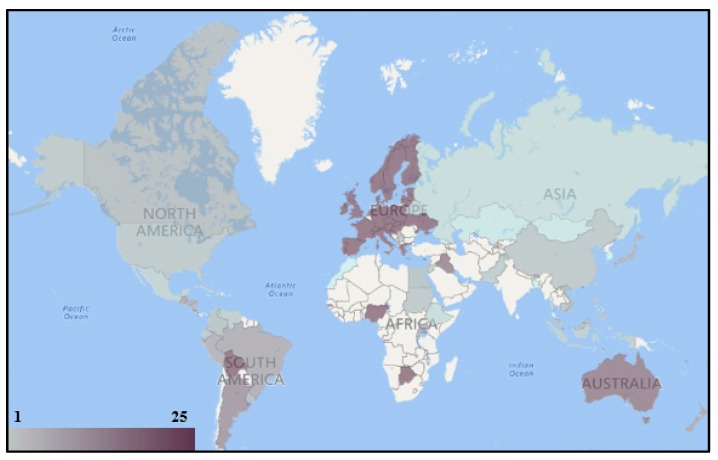

Since hundreds of different pesticides have been registered for use and nations may apply different pesticides based on their situations, 25 pesticides were generally selected to examine if the worldwide nations had provided enough pesticide regulation information based on historical and current usage. These 25 selected pesticides include 14 current widely used pesticides: 2,4-D, Aldicarb, Atrazine, Chlorothalonil, Chlorpyriphos, Diazinon, Dicamba, Diuron, Glyphosate, Malathion, Mancozeb, MCPA, Metolachlor, and Trifluralin, and 11 historically largely used pesticides (the Stockholm Convention POP): Aldrin, Chlordane, DDT, Dieldrin, Endrin, Heptachlor, Toxaphene, Lindane, Endosulfan, Pentachlorophenol, and Bromomethane. Figure 2 illustrates the geographic distribution of nations on regulating the 25 selected pesticides in residential surface soil. A total of 49 nations have regulated the soil RGV for at least one of these 25 pesticides. Only national jurisdictions were applied, and, if a nation had more than one national jurisdiction, the better performing one was selected. For example, the U.S. EPA regulated the RGVs for all of these 25 pesticides, and the U.S. ASTDR provided the RGVs for only eight of the selected pesticides. Therefore, the U.S. EPA was selected here as the U.S. national representative jurisdiction. In Figure 2, a nation with a darker red color means that this nation had regulated more selected pesticides for soil. The Czech Republic, New Zealand, Slovakia, and the U.S. regulated soil RGVs for all the selected pesticides. Malaysia provided the RGV for 24 selected pesticides and the Bahamas regulated for 20 pesticides. The arithmetic mean for the number of selected pesticides which had been regulated with the soil RGV is 9. Some nations in Africa, Asia, and South America did not provide any soil pesticide standard values for the selected pesticides. Some multinational organizations, including both the EU and WHO, regulated the soil RGVs for eight of the selected pesticides. Figure 3 illustrates the geographic distribution of nations regulating the 25 selected pesticides in drinking water. There are 97 nations which provided the pesticide drinking water MCL for at least one of the 25 selected pesticides. Most of the European nations had regulated the MCLs for all selected pesticides, because these nations applied EU standards, which provided individual and total standards for any pesticide. Australia provided the MCLs for 22 selected pesticides and Iraq regulated for 21. Both the U.S. and China regulated the MCLs for 9 of the 25 selected pesticides, while Bangladesh, South Korea, and Morocco had only provided the MCLs for one of the selected pesticides. Some nations in Africa and Asia did not provide any drinking water pesticide standard values for the selected pesticides. The arithmetic mean for the number of selected pesticides which had been regulated with the drinking water MCL is 16. In terms of the multinational organizations, the EU provided all MCLs for these 25 pesticides and the WHO regulated for 13.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of the nations regulating the 25 selected pesticides in residential surface soil.

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of the nations regulating the 25 selected pesticides in drinking water.

4.2. The Most Commonly Regulated Pesticides in Soil and Drinking Water

The most commonly regulated pesticides in this study were defined as pesticides with over 100 soil RGVs or drinking water MCLs. Table 4 summarizes the commonly regulated pesticides by the common name under which they were most often regulated in jurisdictions, CAS No, occurrence frequency (in U.S. jurisdictions and worldwide jurisdictions), the lowest and highest values, and the log orders of variation (LOV, LOV = log {highest value/lowest value}) over which the RGVs and MCLs were scattered. There are 39 most commonly regulated pesticides with either soil RGVs or drinking water MCLs regulated above 100. DDT is the most frequently regulated pesticide in soil with 319 RGVs, made up of 140 RGVs from the U.S. related jurisdictions and 179 RGVs from the jurisdictions outside of the U.S., while 2,4-D is the most frequently regulated pesticides in drinking water with 180 MCLs, including 59 U.S. MCLs and 121 worldwide MCLs. Pesticides including Endosulfan, α-HCH, β-HCH, Bromomethane, and o-Cresol were regulated by over 100 RGVs in soil but less than 13 MCLs in drinking water. There were 125 drinking water MCLs regulated for DBCP, while 31 DBCP soil RGVs were promulgated with only one RGV from the jurisdictions outside of the U.S. There were 22 and 25 pesticides which had been regulated with over 100 soil RGVs and drinking water MCLs, respectively. For these 39 most commonly regulated pesticides, the state of Idaho had specified the lowest soil RGVs for at least 7 pesticides, and both Oregon and Serbia provided the lowest RGVs for at least four of the most commonly regulated pesticides. Texas specified the highest soil RGVs for at least 14 of the commonly regulated pesticides, Guam (U.S.) provided the highest RGVs for five pesticides, and the U.S. Military jurisdiction regulated for four pesticides. Regardinf drinking water, the EU and the jurisdictions which applied the EU standards specified the lowest drinking water MCLs for at least 21 of the most commonly regulated pesticides, and Wyoming provided the lowest MCLs for at least 9 pesticides. The EU provided the pesticide drinking water MCLs quite conservatively, because the jurisdiction specified 0.0001 mg/L for an individual pesticide. On the other hand, the U.S. Military jurisdiction promulgated the highest MCLs for at least 12 pesticides; this is probably because the jurisdiction derived the MCL based on adult body weight and short time exposure conditions. Vietnam regulated the highest MCLs for 9 of the commonly regulated pesticides, and Mexico provided the highest MCLs for 5.

Table 4.

Summary of the most commonly regulated pesticides in residential surface soil and drinking water.

| No. | Pesticide Common Name | CAS No. | No. of RGVs (U.S., world) | RGV Lowest Value (mg/kg) | RGV Highest Value (mg/kg) | RGV LOV | No. of MCLs (U.S., world) | MCL Lowest Value (mg/L) | MCL Highest Value (mg/L) | MCL LOV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DDT | 50-29-3 | 319 (140, 179) | 0.00033; Oregon + 1 | 11,300.0; Netherlands | 7.53 | 115 (13, 102) | 0.00000022; CNMI 2 | 2.8; U.S. Military | 7.11 |

| 2 | Lindane | 58-89-9 | 247 (133, 114) | 0.000005; Poland | 707.0; New Zealand | 8.15 | 166 (58, 108) | 0.000019; CNMI | 2; Mexico + | 5.02 |

| 3 | Dieldrin | 60-57-1 | 247 (121, 126) | 0.0000081; Oregon + | 63,000.0; Illinois | 9.89 | 109 (6, 103) | 0.000000052; CNMI | 0.03; Mauritius + | 5.76 |

| 4 | DDE | 72-55-9 | 244 (118, 126) | 0.00033; Oregon + | 7830.0; Netherlands | 7.38 | 76 (4, 72) | 0.00000022; Wyoming + | 1.0; Mexico | 6.66 |

| 5 | DDD | 72-54-8 | 243 (122, 121) | 0.00033; Oregon + | 5160.0; U.S. Military | 7.19 | 74 (3, 71) | 0.00000022; Wyoming | 1.0; Mexico | 6.66 |

| 6 | Aldrin | 309-00-2 | 242 (119, 123) | 0.00006; Serbia + | 1000.0; Guam + | 7.22 | 110 (6, 104) | 0.000000049; Wyoming+ | 0.03; Hungary + | 5.79 |

| 7 | Chlordane | 57-74-9 or 12789-03-6 | 224 (143, 81) | 0.00003; Serbia + | 1000.0; Guam + | 7.52 | 163 (61, 102) | 0.0000008; Wyoming + | 0.2; Mexico + | 5.40 |

| 8 | Endrin | 72-20-8 | 217 (129, 88) | 0.00004; Singapore + | 4240.0; U.S. Military | 8.03 | 136 (60, 76) | 0.000005; Gambia | 0.28; U.S. Military | 4.75 |

| 9 | Heptachlor | 76-44-8 | 212 (136, 76) | 0.0003; Serbia | 1000.0; Guam + | 6.52 | 137 (59, 78) | 0.00000079; Wyoming + | 0.05; Russia | 5.80 |

| 10 | Pentachloropnenol | 87-86-5 | 191 (125, 66) | 0.005; Norway | 6500.0; Ohio | 6.11 | 153 (57, 96) | 0.0001; EU + | 9.0; Vietnam | 4.95 |

| 11 | Endosulfan | 115-29-7 | 177 (103, 74) | 0.00001; Singapore + | 3000.0; Massachusetts | 8.48 | 13 (1, 12) | 0.02; Australia + | 0.07; U.S. Military | 0.54 |

| 12 | Heptachlor Epoxide | 1024-57-3 | 166 (121, 45) | 0.0000002; Serbia + | 1000.0; Guam + | 9.70 | 117 (57, 60) | 0.00000039; Wyoming+ | 0.1; Croatia | 6.41 |

| 13 | α-HCH | 319-84-6 | 162 (90, 72) | 0.00011; North Carolina | 7100.0; Texas | 7.81 | 7 (4, 3) | 0.0000026; Wyoming+ | 0.02; (Australia) Queensland | 3.88 |

| 14 | Methoxychlor | 72-43-5 | 158 (118, 40) | 0.046; Alberta | 9170.0; Missouri | 5.30 | 159 (58, 101) | 0.0001; EU + | 20.0; Mauritius + | 5.30 |

| 15 | β-HCH | 319-85-7 | 154 (74, 80) | 0.00037; North Carolina | 127.0; U.S. Military | 5.54 | 10 (8, 2) | 0.0000091; Wyoming+ | 0.7; U.S. Military | 4.89 |

| 16 | 2,4-D | 94-75-7 | 147 (103, 44) | 0.04; Moldova | 12,000.0; Oregon + | 5.78 | 180 (59, 121) | 0.0001; EU + | 30.0; Mexico + | 5.48 |

| 17 | Atrazine | 1912-24-9 | 144 (76, 68) | 0.00005; Poland | 12,000.0; Texas | 8.38 | 163 (58, 105) | 0.0001; EU + | 2.0; Vietnam | 4.30 |

| 18 | Toxaphene | 8001-35-2 | 142 (102, 40) | 0.00042; SFBWQ | 500.0; Guam + | 6.08 | 99 (54, 45) | 0.0000028; Wyoming + | 0.014; U.S. Military | 4.70 |