SUMMARY

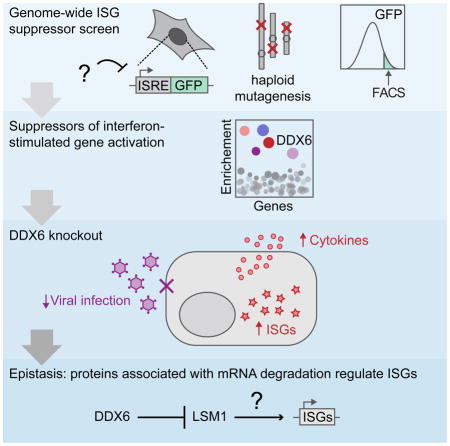

The innate immune system tightly regulates activation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) to avoid inappropriate expression. Pathological ISG activation resulting from aberrant nucleic acid metabolism has been implicated in autoimmune disease, however the mechanisms governing ISG suppression are unknown. Through a genome-wide genetic screen, we identified DEAD-box helicase 6 (DDX6) as a suppressor of ISGs. Genetic ablation of DDX6 induced global upregulation of ISGs and other immune genes. ISG upregulation proved cell intrinsic, imposing an antiviral state and making cells refractory to divergent families of RNA viruses. Epistatic analysis revealed that ISG activation could not be overcome by deletion of canonical RNA sensors. However, DDX6 deficiency was suppressed by disrupting LSM1, a core component of mRNA degradation machinery, suggesting that dysregulation of RNA processing underlies ISG activation in DDX6 mutant. DDX6 is distinct among DExD/H helicases that regulate the antiviral response in its singular ability to negatively regulate immunity.

Keywords: Interferon, Viral Infection, Genome-scale screen, Autoimmunity, Interferon-stimulated genes, DDX6, DEAD-box helicase, Cell intrinsic immunity

In brief

Pathological interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) expression contributes to autoimmunity yet the mechanisms governing ISG suppression remain obscure. Lumb et al. identify DDX6 as a potent ISG suppressor. DDX6 prevents activation of IFN-independent cell intrinsic immunity. DDX6 works via LSM1, uncovering a potential role for the mRNA degradation machinery in ISG suppression.

INTRODUCTION

Interferons (IFNs) are potent multifunctional cytokines that play a critical role in innate immunity against viruses. Upon viral infection, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns. PRRs then trigger signaling cascades resulting in the production of IFNs through interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) and pro-inflammatory cytokines via NF-κB (Iwasaki, 2012). IFN production and the subsequent activation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) by the JAK-STAT pathway have been classically associated with viral infection. However, this paradigm has been challenged by the discovery of basal expression levels of IFN in the absence of infection and the constitutive upregulation of type I interferon in certain autoimmune diseases (Crow and Manel, 2015; Lienenklaus et al., 2009).

It is becomingly increasingly clear that low-level IFN production in the absence of infection plays a vital role in diverse biological processes including maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell niche, immune cell function, and bone remodeling (Gough et al., 2012; Lienenklaus et al., 2009). Such spontaneous IFN also plays a crucial role in priming cells, allowing rapid and robust responses upon microbial detection (Hata et al., 2001). As a result, IFN-mediated homeostasis must be very tightly regulated, as prolonged or aberrant exposure is deleterious. Perturbations of IFN expression or signaling contribute to the etiology of several autoimmune diseases, dysregulated antiviral responses, and cancer (Corrales et al., 2017; Crow and Manel, 2015; Davidson et al., 2014; Pylaeva et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2013). Many of these pathological conditions arise when PRRs inappropriately sense endogenous nucleic acids and it is now clear that aberrant nucleic acid metabolism and DNA damage are responsible for a multitude of autoimmune diseases (Crowl et al., 2017). However, the molecular mechanisms that titrate ISG expression and how signaling perturbations cause disease remain obscure.

Here we performed an unbiased genome-wide screen to identify genes that repress spontaneous activation of ISGs in the absence of infection. We reveal a role for the DEAD-box RNA helicase, DDX6, in preventing aberrant ISG expression and uncover a functional role of LSM1 in this process.

RESULTS

Identification of genes that prevent inappropriate ISG activation

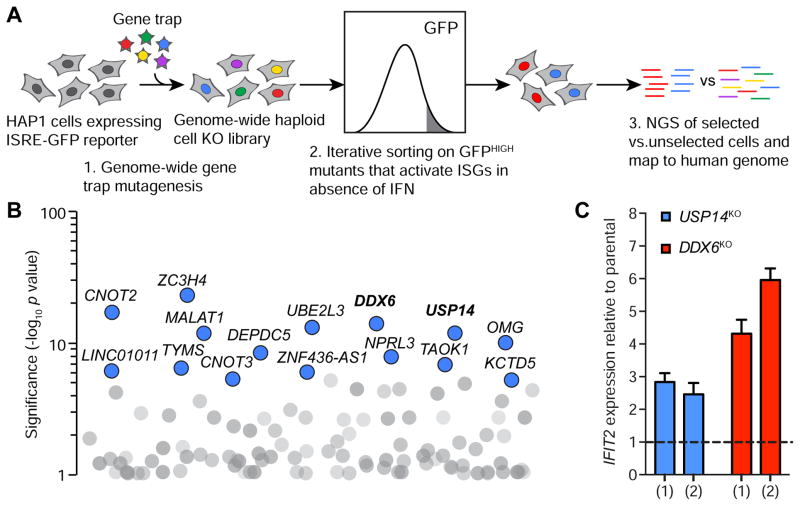

To discover genes that prevent aberrant ISG activation in the absence of both infection and exogenous IFN, we exploited an unbiased, genome-wide screening strategy of insertional mutagenesis in haploid human cells (Carette et al., 2009). This approach creates knockout alleles on a large scale and has been successfully used to dissect host-pathogen interactions (Puschnik et al., 2017); here we adapted the methodology to screen for genes that prevent aberrant ISG activation.

We developed a reporter cell line to determine ISG expression and scrutinize the activation of IFN pathway using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). ISGs can be induced directly by IRFs upon PRR activation and also via the production of IFN and subsequent JAK-STAT signaling. To interrogate both pathways of ISG induction, we selected the interferon-sensitive responsive element (ISRE) from IFIT2 (ISG54), which can be activated by either pathway (Levy et al., 1986; Wathelet et al., 1992). We created a reporter cell line containing the ISRE from IFIT2 in the human haploid cell line HAP1 (HAP1 ISRE-GFP) and overexpressed IFNLR1 to sensitize the cells to IFNλ. As expected, a strong induction of GFP was observed following IFNλ treatment (Figure S1A). To rigorously benchmark the reporter cell line, we performed a genome-wide screen for well-characterized positive regulators crucial for the IFN pathway (Figure S1B). HAP1 ISRE-GFP was mutagenized using insertional mutagenesis to create a library of knockouts (Carette et al., 2011a). Mutants cells refractory to IFN stimulation were isolated through iterative rounds of FACS. All canonical components of the type III IFN pathway were identified (Wack et al., 2015), establishing that the IFN pathway remains functional in HAP1 cells and that our approach can accurately identify key pathway components (Figure S1C; Table S1). Although IFNLR1 was not anticipated in this instance because of ectopic overexpression in the haploid background, we still found significant enrichment that did not meet our cutoff.

Having validated our reporter cell line, we performed a screen using the same knockout library to identify genes that prevent ISG activation in the absence of IFN (Figure 1A). In this screen, we used FACS to isolate mutants that displayed constitutive reporter activation without the addition of IFN. The top 15 significant hits are shown in Figure 1B (see Table S2 for full list). We chose DDX6 (p = 8.67E-15) and USP14 (p = 1.22E-12) for validation and follow-up experiments based on their statistical ranking and literature indicating that their proteins may play a role in ISG regulation. DDX6 encodes the decapping coactivator, DEAD-box helicase 6, which localizes to processing bodies (P-bodies) where it plays a central role in RNA metabolism (Ostareck et al., 2014). Other members of the DExD/H-box helicase family play crucial roles in ISG regulation, such as the RNA-sensors, RIG-I and MDA5 (Fullam and Schröder, 2013). USP14 encodes a cytoplasmic deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB), ubiquitin specific peptidase 14. During DNA viral infection, USP14 modulates cGAS stability, indicating a function in immunity (Chen et al., 2016). Furthermore, ubiquitination is critical for the activation of many components of the IFN pathway and negative feedback regulation partially depends on DUBs (Heaton et al., 2016).

Figure 1. Unbiased haploid screen identifies genes that prevent aberrant activation of interferon-stimulated genes.

(A) Schematic of the genome-wide screening approach. NGS, next generation signaling. (B) Screen results for genes that prevent activation of ISGs in the absence of IFN. The y axis represents significance of enrichment of gene trap insertions in genes in selected cells compared to unselected HAP1 cells (Fisher’s exact test corrected for false discovery rate). Each circle represents a specific gene. The top 15 significant genes are colored blue. Genes with −log10 p value>1 are shown. Genes in bold were chosen for further study. (C) IFIT2 qPCR of USP14KO and DDX6KO HAP1 cells. Two independently generated knockout clonal cell lines for each genotype are shown by (1) and (2). Expression is relative to parental HAP1 cells shown as a black dotted line. Data are mean ± SEM of three separate RNA extractions.

To validate the roles of DDX6 and USP14 in ISG repression, we used CRISPR-CAS9 genome engineering to generate isogenic DDX6-knockout (DDX6KO) and USP14-knockout (USP14KO) cell lines (Table 1). We performed subsequent analyses using two independently generated knockout clonal cell lines for DDX6 and USP14, minimizing any potential off-target effects of CAS9. Given our use of the ISRE from IFIT2 in our reporter, we measured endogenous IFIT2 expression in our knockout cell lines by quantitative PCR (qPCR). As expected, DDX6KO and USP14KO cells showed enhanced expression of IFIT2, with DDX6KO cells displaying a stronger increase (Figure 1C). This suggests that DDX6 and USP14 suppress IFIT2 expression.

Table 1.

Genotyping of mutant cell lines.

| Cell type | Gene edited | Cell line | Sequence | Editing event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHDF | DDX6 | WT | GAAAAACACCAACACAATCAATAATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | N/A |

| DDX6KO(1) | GAAAAACACCAACATCCAGGGTGGAAGCGGAGCTACTAACTT | homozygous blast. i. | ||

| DDX6KO(2) | GAAAAACACCAACATCCAGGGTGGAAGCGGAGCTACTAACTT | homozygous blast. i. | ||

| HuH7 | DDX6 | DDX6KO(1) | GAAAAACACCAACA-AATCAATAATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | 1 bp d. |

| DDX6KO(1) | GAAAAACACCA--ACAATCAATAATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | 2 bp d. | ||

| DDX6KO(2) | GAAAAACACCAACA-AATCAATAATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | 1 bp d. | ||

| DDX6KO(2) | GAAAAACACCA--ACAATCAATAATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | 2 bp d. | ||

| HAP1 | DDX6 | DDX6KO(1) | GAAAAACACCAACA----CAATAATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | 4 bp d. |

| DDX6KO(2) | GAAAAACACCAACA--------AATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | 8 bp d. | ||

| DDX6KO(3) | GAAAAACACCA--ACAATCAATAATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | 2 bp d. | ||

| DDX6KO(4) | GAAAAACACCA--ACAATCAATAATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | 2 bp d. | ||

| DDX6KO used in addback expts | GAAAAACACCA--ACAATCAATAATGGCACTCAGCAGCAAGC | 2 bp d. | ||

| USP14 | WT | TGGTATTCAAGGCTCAGCTGTTTGCGTTGACTGGAGTCCAGC | N/A | |

| USP14KO (1) | TGGTATTCAAGGCTCAGCTGTTTGCGT--------------C | 14 bp d | ||

| WT | GGTGTAGAATTGAATACAGATGAACCTCCAATGGTATTCAAG | N/A | ||

| USP14KO (2) | GGTGTAGAATTGAATACAG-----------ATGGTATTCAAG | 11 bp d. | ||

| LSM1 | WT | CCCCAGAAAAGCACTTGGTTCTGCTTCGAGATGGAAGGACAC | N/A | |

| LSM1KO(1) | CCCCAGAAAAGCACTTGGTTCTGCTT--AGATGGAAGGACAC | 2 bp d. | ||

| WT | TGGTTCTGCTTCGAGATGGAAGGACACTTATAGGCTTTTTAA | N/A | ||

| LSM1KO(2) | TGGTTCTGCTTCGAGATGGAAGGACACTTTATAGGCTTTTTA | 1 bp i. | ||

| STAT1 | WT | TTCATTTGCCACCATCCGTTTTCATGACCTCCTGTCACAGCT | N/A | |

| DDX6_STAT1KO(1) | TTCATTTGCCACCAATCCGTTTTCATGACCTCCTGTCACAGC | 1 bp i. | ||

| DDX6_STAT1KO(2) | TTCATTTGCCA----CCGTTTTCATGACCTCCTGTCACAGCT | 4 bp d. | ||

| DDX6_STAT1KO(3) | TTCATTTGCCACCA-CCGTTTTCATGACCTCCTGTCACAGCT | 1 bp d. | ||

| MAVS | WT | CTTCCAGCCCCTGGCCCGTTCCACCCCCAGGGCAAGCCGCTT | N/A | |

| MAVSKO | CTTCCAGCCCCTGG--CGTTCCACCCCCAGGGCAAGCCGCTT | 2 bp d. | ||

| MDA5 | WT | TGGCACCTTGGTTGGACTCGGGAATTCGTGGAGGCCCTCCGG | N/A | |

| MDA5KO | TGGCACCTTGGTTGGACTCGGGAATTCG-------------G | 13 bp d. | ||

| RIG-I | WT | CAGGCTGAGAAAAACAACAAGGGCCCAATGGAGGCTGCCACA | N/A | |

| RIG-IKO | CAGGCTGAGAAAAACAA-----------TGGAGGCTGCCACA | 11 bp i. | ||

| PKR | WT | AAAAAATGCCGCAGCCAAATTAGCTGTTGAGATACTTAATAA | N/A | |

| PKRKO | AAAAAAT-------------TAGCTGTTGAGATACTTAATAA | 13 bp d. |

Guide sequences are in bold, insertions are in italics. Deletions are denoted with dashes. d., deletion. i., insertion. N/A, not applicable. Blast., blasticidin

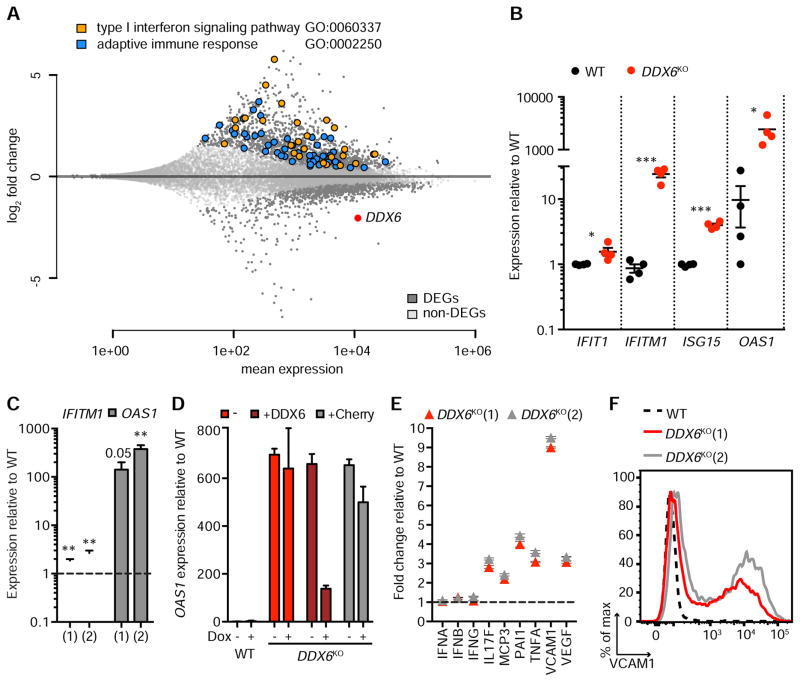

Transcriptional profiling of USP14 and DDX6 knockouts

To further validate the activation of ISGs in DDX6KO and USP14KO cells we performed transcriptional profiling using RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). An absence of DDX6 resulted in the upregulation of 347 genes (p<0.001, log2FC>2) and the downregulation of 82 genes (p<0.001, log2FC<-2) (Figure 2A; Table S3). Unbiased pathway analysis of upregulated genes revealed an enrichment of signatures activated after IFN exposure or viral infection. The two most enriched gene ontology (GO) categories were type I IFN signaling pathway (GO:0060337) and adaptive immune response (GO:0002250) (Table S4). GO:0060337 encompasses genes required for IFN signaling, in addition to many ISGs including IFIT2 (Table S5). Most of the genes in GO: 0060337 were upregulated in the DDX6KO dataset (Figure S2A). These data indicate that DDX6 deficiency causes specific and profound upregulation of ISGs and other genes involved in adaptive immunity and inflammation.

Figure 2. DDX6 regulates ISGs and adaptive immune genes independently of IFN.

(A) Global gene expression in WT and DDX6KO HAP1 cells. Dark grey dots are differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Light grey dots are non-DEGs. The two most significantly enriched GO terms in upregulated DEGs are GO:0060337 (orange circles) and GO:0002250 (blue circles). Red dot, DDX6. (B) qPCR analyses of IFIT1, IFITM1, ISG15 and OAS1 in WT and DDX6KO HAP1 cells. Each circle represents a unique clonal cell line as determined by genotyping (DDX6KO1–4; Table 1). Data are mean ± SEM of the clonal cell lines (n=4). (C) qPCR analyses of IFITM1 and OAS1 in NHDF cells. Two unique DDX6KO NHDF clones are depicted by (1) and (2). WT is shown as a black dotted line. Data are mean ± SEM of four independent RNA extractions. (D) OAS1 qPCR in WT, DDX6KO or DDX6KO complemented with DDX6 (+DDX6) or vector control expressing Cherry (+Cherry), ± doxycycline (Dox) treatment. – denotes uncomplemented DDX6KO cells. Data are mean ± SEM of three separate RNA extractions. (E) Cytokine secretion in WT (black dotted line) and two independently generated DDX6KO cell lines, DDX6KO(1) and DDX6KO(2). Cytokines with a fold change >2 are displayed except for IFNA, IFNB, and IFNG, which were unchanged between WT and DDX6KO HAP1 cells. Data are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (F) VCAM1 surface expression in WT and DDX6KO(1) and DDX6KO(2) HAP1 clones.

By contrast, deletion of USP14 had a modest effect on global gene expression and only USP14 was identified as a DEG using the stringent criteria applied to the DDX6 dataset (p<0.001, log2FC<-2) (Figure S2B; Table S6). However, we observed a significant increase in IFITM1 expression when we applied a cut-off of p<0.05. We validated our RNA-seq data by qPCR of IFITM1, which showed increased expression in DDX6 and USP14 knockouts as expected (Figure S2C). Collectively, these data suggest that both DDX6 and UPS14 play functional roles in ISG suppression.

DDX6 prevents cell intrinsic activation of ISGs independently of IFN

Given the profound impact of DDX6 deficiency on ISGs, we decided to examine the role of DDX6 in ISG repression in more detail. We performed qPCR on several ISGs in DDX6KO cells and noted significant increases in expression levels, with OAS1 displaying the largest increase (Figure 2B). Having confirmed that DDX6 ablation activated ISGs in transformed HAP1 cells, we verified the physiological relevance of our findings by knocking out DDX6 in primary Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts (NHDF, Table 1). We measured IFITM1 and OAS1 by qPCR in DDX6KO NHDF cells and observed a marked increase in their expression (Figure 2C). These data indicate that DDX6 prevents ISG activation in transformed and primary human cells.

Genetic complementation of DDX6 in DDX6KO HAP1 cells reduced OAS1 levels, confirming that the elevated expression in DDX6KO cells was caused by DDX6 deletion (Figures 2D and S2D). Elevated ISG transcript levels corresponded to elevated protein expression, evidenced by increased IFITM1 at the surface of DDX6KO cells (Figure S2E). Transcriptional profiling revealed that while many genes involved in innate and adaptive immunity were upregulated, IFN mRNA levels (IFNα, IFNβ, IFNλ and IFNγ) were unaltered in the absence of DDX6. To verify these results on the protein level, we performed cytokine profiling of a subset of genes involved in immunity. Indeed, DDX6KO cells did not secrete IFNs but showed elevated release of multiple cytokines (Figure 2E). The most pronounced effect of DDX6 ablation was on VCAM1 secretion. This was accompanied by an increase in VCAM1 on the cell surface of DDX6 knockouts (Figures 2F and S2F).

In DDX6 deficient cells, ISG upregulation occurred without concurrent IFN expression (Figure 2A, E). To ensure that HAP1 cells are capable of producing IFN, we infected WT HAP1 cells with influenza virus (INFVPR8) or Sendai virus (SENV) and detected increases IFNA and IFNB expression by qPCR (Figure S2G). We also detected elevated IFNB secretion in WT HAP1 cells infected with INFVPR8 (Figure S2H). These data suggest that defective IFN signaling in HAP1 is not responsible for the lack of IFN expression in DDX6KO cells, but rather that ISG activation occurs independently of IFN-signaling upon DDX6 deletion.

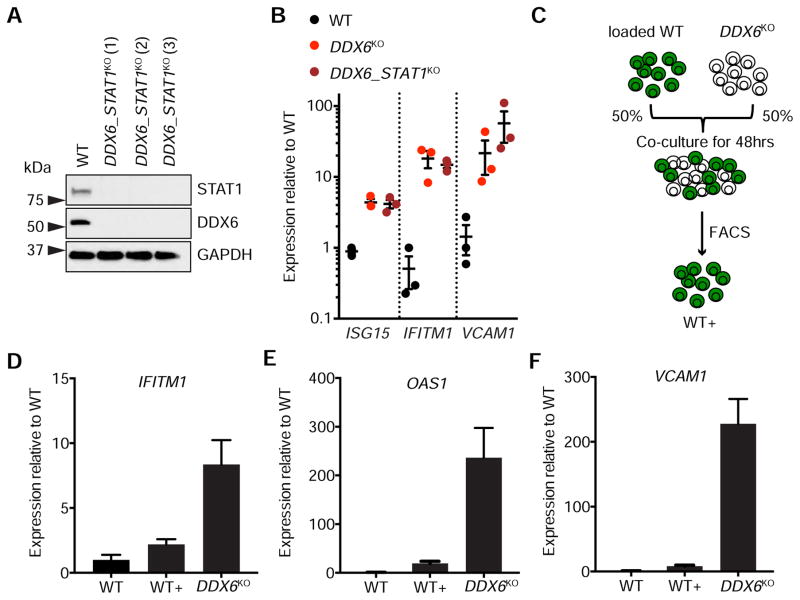

To test this possibility we created a DDX6 STAT1 double knockout (DDX6_STAT1KO) (Table 1 and Figure 3A) and measured ISG levels by qPCR. As expected, deletion of STAT1 made cells incapable of responding to exogenous IFN (Figure S3A–B). However, elevated ISG and VCAM1 levels observed in DDX6KO cells were not rescued by STAT1KO, suggesting that DDX6 regulates ISG and VCAM1 independently from canonical STAT1-mediated IFN signaling (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. ISG activation occurs independently of STAT1 and is cell intrinsic.

(A) Protein expression of STAT1 and DDX6 in three unique clonal DDX6_STAT1KO cell lines. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) qPCR of ISG15, IFITM1 and VCAM1 in WT, DDX6KO and DDX6_STAT1KO HAP1 cells. Each circle represents a unique clonal cell line (DDX6_STAT1KO(1–3); Table 1). Data are mean ± SEM of the clones (n=3). (C) Schematic depicting the co-culture of WT and DDX6KO cells. WT+ refers to WT cells that have been grown in the presence of DDX6KO cells. (D–F) qPCR of IFITM1, OAS1 and VCAM1 in WT, DDX6KO and WT cells grown in the presence of DDX6KO cells (WT+). Data are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

We hypothesized that ISG induction in DDX6KO cells may occur via a cell intrinsic mechanism. To investigate this possibility, we developed a cell-tracking assay to determine whether elevated ISG expression in DDX6KO cells could be conferred onto WT cells (Figure 3C). As a control, we examined if the dye used to track cells (CFSE) could cause ISG induction. We loaded WT cells with dye and mixed them with unloaded WT cells. After co-culture, we isolated CFSE positive cells by FACS and measured expression levels of several ISGs by qPCR (Figure S3C). CFSE loading had a minimal impact on ISG induction in WT cells (Figure S3D).

We next loaded WT cells with dye and co-cultured them with unloaded DDX6KO cells. We isolated CFSE positive WT (WT+) cells by FACS (Figure S4E) and measured ISG expression in WT+ cells by qPCR to ascertain if the derepression of ISGs was transferrable. Although we observed a modest induction of ISGs in WT+ cells, the effect was minimal compared to ISG expression in DDX6KO cells and could be explained in part by CSFE loading (Figure 3D–F). These data indicate that cytokine-mediated ISG activation is unlikely to contribute substantially to the DDX6 knockout phenotype because ISG expression could not be transferred onto neighboring cells. Taken together, these data suggest that elevated ISG expression in DDX6KO cells occurs via a cell intrinsic, interferon-independent mechanism.

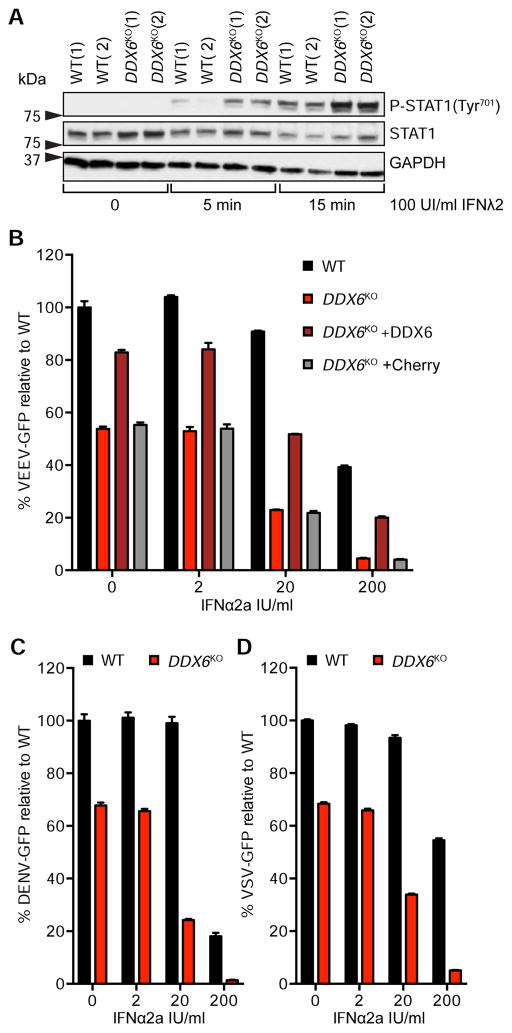

DDX6 deficiency primes the IFN system for enhanced antiviral response

We hypothesized that loss of DDX6 primes cells for an amplified antiviral innate immune response. This could occur as a result of constitutive expression of ISGs in DDX6KO cells which are directly antiviral or because components of the antiviral sensing machinery are ISGs themselves, or a combination of both. As a result, the upregulation of PRR and IFN signaling components in DDX6KO cells may sensitize them to IFN. We tested this by probing STAT1 phosphorylation (P-STAT1) after IFN treatment in HAP1 cells. As expected, DDX6KO cells were more responsive to IFN stimulation than WT cells, evidenced by enhanced P-STAT1 expression (Figure 4A). We detected increases in total STAT1, IFNAR1 and IRF3 protein expression upon DDX6 deletion but could not detect phosphorylation of IRF3 in DDX6KO cells at steady state (Figures 4A, S4A–C). In addition, we observed upregulation of JAK-STAT components and PRRs at the mRNA level (Figure S4D). These data indicate that the enhanced sensitivity of DDX6KO cells to IFN is due to increased expression of multiple IFN signaling components, which occurs independently of IRF3 phosphorylation.

Figure 4. DDX6 deficiency primes the IFN system for enhanced antiviral response.

(A) Total STAT1 and phosphorylation of STAT1 (P-STAT1 Tyr701) in WT and DDX6KO HAP1 cells ± IFNλ2. GAPDH served as a loading control. Two unique clones were included for WT and DDX6KO cells, denoted by (1) and (2). (B) VEEV-GFP infection of HuH7 cells. WT, DDX6KO, and DDX6KO complemented with DDX6 or a vector control expressing Cherry, were treated with the indicated amounts of IFN overnight and then infected with VEEV-GFP. (C) DENV-GFP infection of WT or DDX6KO HuH7 cells pre-treated with IFN overnight. (D) VSV-GFP infection of WT or DDX6KO HuH7 cells pre-treated with IFN overnight. Data are mean ± SEM of three independent infections.

We next asked whether the constitutive activation of ISGs in DDX6 knockout cells translates into an increased antiviral state. To test this question we used dengue virus (DENV). Even though DENV has evolved effective ways to antagonize the IFN response (Gack and Diamond, 2016), replication can be attenuated when cells are pretreated with exogenous IFN, thus indicating that primed cells are able to overcome DENV antagonism (Ho et al., 2005). We first examined DENV infection in DDX6KO cells and saw that DENV replication was attenuated over time, a response that indicated that DDX6KO cells were primed even in absence of IFN (Figure S4E).

To aid in further studies, we created an isogenic DDX6 knockout in HuH7, a hepatocyte derived cellular carcinoma cell line more permissive to viral replication than HAP1 cells (Figure S4F; Table 1). Consistent with our study of HAP1 and NHDF DDX6 knockouts, DDX6KO HuH7 cells also had constitutive immune gene expression, further supporting the relationship between DDX6 deletion and ISG activation in multiple cell types (Figure S4G–I). To test if the antiviral response was more robust in HuH7 cells depleted of DDX6, we infected DDX6KO with a variety of RNA viruses known to be sensitive to IFN (Basu et al., 2006; Gauntt and Lockart, 1966; Grieder and Vogel, 1999). In these experiments we primed with IFNα as the viruses used in this study are more responsive to type I than type III IFN.

Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV-GFP) infection was blunted in DDX6KO HuH7 cells, which could be restored by genetic complementation of DDX6 (Figure 4B). We could exacerbate the defect in VEEV-GFP replication by pre-treating DDX6KO cells with IFN prior to infection, providing further support that DDX6 depletion primes the immune system for an amplified response. DENV-GFP infection in DDX6KO HuH7 cells followed the same pattern, as did infection with Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-GFP) (Figure 4C–D). In addition to members of the Flaviviridae (DENV), Togaviridae (VEEV) and Rhabdoviridae (VSV), we also tested Mengovirus (MENGV), a member of the Picornaviridae. MENGV replication was diminished in DDX6KO cells and, as expected, was further aggravated by pre-stimulating cells with IFN (Figure S4J). Collectively, these data show that loss of DDX6 activates the expression of immune genes, priming the innate immune system for an amplified type I IFN response when challenged by a broad range of viruses.

Epistatic analysis in DDX6KO cells

DDX6 is a key regulator of RNA metabolism and formation of P-bodies, which are sites of mRNA storage and decay (Andrei et al., 2005; Ayache et al., 2015; Chu and Rana, 2006; Ostareck et al., 2014). Aberrant RNA metabolism can inadvertently trigger PRRs via the accumulation of self nucleic acids. For example, mutations in SKIV2L, a component of the RNA exosome, produce self nucleic acid accumulation during the unfolded protein response. Failure to degrade these RNAs triggers autoimmunity via PRR and subsequent MAVS signaling (Eckard et al., 2014). We hypothesized that loss of DDX6 could trigger the accumulation of self nucleic acids associated with aberrant RNA processing, which would activate PRRs and cause inflammation. To test this we genetically dissected the pathway by which DDX6 prevents ISG activation. We created knockouts in DDX6KO HAP1 cells of key components in the RNA surveillance machinery (Figure S5A–F; Table 1). We discovered that deleting MAVS, MDA5, RIG-I or PKR in DDX6KO HAP1 cells could not rescue OAS1 or IFITM1 activation. This suggests that ISG activation in DDX6KO is not exclusively dependent on any one of these genes (Figures 5A and S5G).

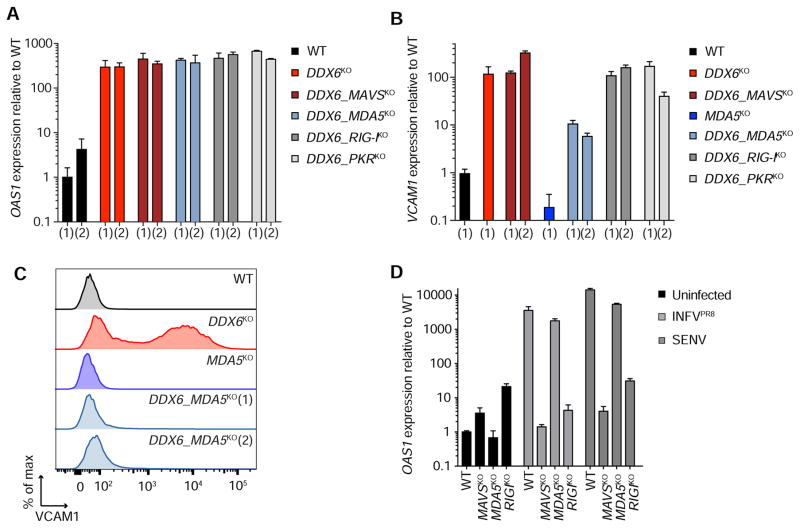

Figure 5. VCAM1 upregulation is dependent on MDA5 and can be uncoupled from ISG upregulation.

(A) OAS1 qPCR in WT, DDX6KO, and DDX6KO with an additional knockout of MAVS (DDX6_MAVSKO), MDA5 (DDX6_MDA5KO), RIG-I (DDX6_RIG-IKO), and PKR (DDX6_PKRKO) HAP1 cells. Two unique clones for each genotype are denoted by (1) and (2). Data are mean ± SEM of three independent RNA extractions. (B) qPCR of VCAM1 in WT, DDX6KO and DDX6_MAVSKO, MDA5KO, DDX6_MDA5KO, DDX6_RIG-IKO, and DDX6_PKRKO HAP1 cells. Independent knockouts are denoted by (1) and (2). Data are mean ± SEM of three independent RNA extractions. (C) VCAM1 surface expression in WT, DDX6KO, MDA5KO and two independent DDX6_MDA5KO HAP1 cells. (D) qPCR of OAS1 in WT, MAVSKO, MDA5KO and RIG-IKO HAP1 cells infected with influenza virus (INFVPR8) and Sendai virus (SENV). Data are mean ± SEM of three independent RNA extractions. The experiment was performed three times and a representative is shown.

Surprisingly, we found that DDX6 MDA5 double knockout cells (DDX6_MDA5KO) had drastically reduced VCAM1 expression (Figure 5B). To verify that the reduction in VCAM1 was accompanied by deceased protein expression, we measured surface levels of VCAM1 in DDX6_MDA5KO cells. We saw that deletion of MDA5 in DDX6KO cells reduced VCAM1 at the cell surface down to WT levels, indicating an epistatic relationship between MDA5 and DDX6 (Figure 5C). Because MAVS and MDA5 are in a shared pathway, we next tested whether MAVS deletion in DDX6KO cells could similarly rescue VCAM1 levels. Intriguingly, DDX6_MAVSKO cells displayed elevated VCAM1 activation (Figure 5B). This suggests that the signal resulting from MDA5 activation in DDX6KO cells is not solely MAVS dependent and that VCAM1 upregulation can be decoupled from ISG activation. Our data highlights that DDX6 limits activation of MDA5 to repress VCAM1 release and that the phenotype caused by DDX6 deletion is multifactorial.

Deleting the canonical RNA sensing and signaling machinery failed to rescue ISG activation in DDX6KO cells and led us to investigate the functionality of RNA sensing pathways in our knockout cells. We infected MAVSKO, MDA5KO and RIG-IKO cells with INFVPR8 and SENV and measured ISG expression by qPCR (Figure 5D). In accordance with the literature, we found that OAS1 induction during INFVPR8 and SENV infection was dependent on MAVS and RIG-I (Kato et al., 2006). The same pattern was repeated when we measured IFITM1 activation during infection (Figure S5H). These data indicate that the MAVSKO and RIG-IKO cell lines are defective for viral RNA sensing and confirm the functionality of these pathways in WT cells. Thus, constitutive ISG activation in cells depleted of DDX6 is not solely dependent on the canonical RNA surveillance machinery involving MAVS.

DDX6 prevents aberrant activation of ISGs via LSM1

DDX6 has an role in P-body assembly, acting with other decay factors such as DCP1A and the LSM1-7 complex to promote mRNA degradation (Andrei et al., 2005; Ayache et al., 2015; Chu and Rana, 2006; Coller et al., 2001; Fischer and Weis, 2002). As expected, in HAP1 cells both DDX6 and LSM1 colocalized with DCP1A in P-bodies (Figures S6A and 6A). In keeping with its role in P-body assembly, we observed a dramatic dispersal of P-body components in DDX6KO cells (Figure 6A). To isolate the role of P-bodies in ISG activation, we used an alternative method to deplete P-bodies by knocking out LSM1. LSM1 deletion resulted in a similar dispersal of DCP1A but in stark contrast to DDX6KO, did not result in ISG activation (Figures 6A–B and S6B). While DDX6 protein expression remained unchanged, DDX6 dispersed completely throughout LSM1KO cells (Figure 6C–D). This data suggests that aberrant ISG activation does not require P-body integrity, pointing to a specific function of DDX6 that is P-body independent.

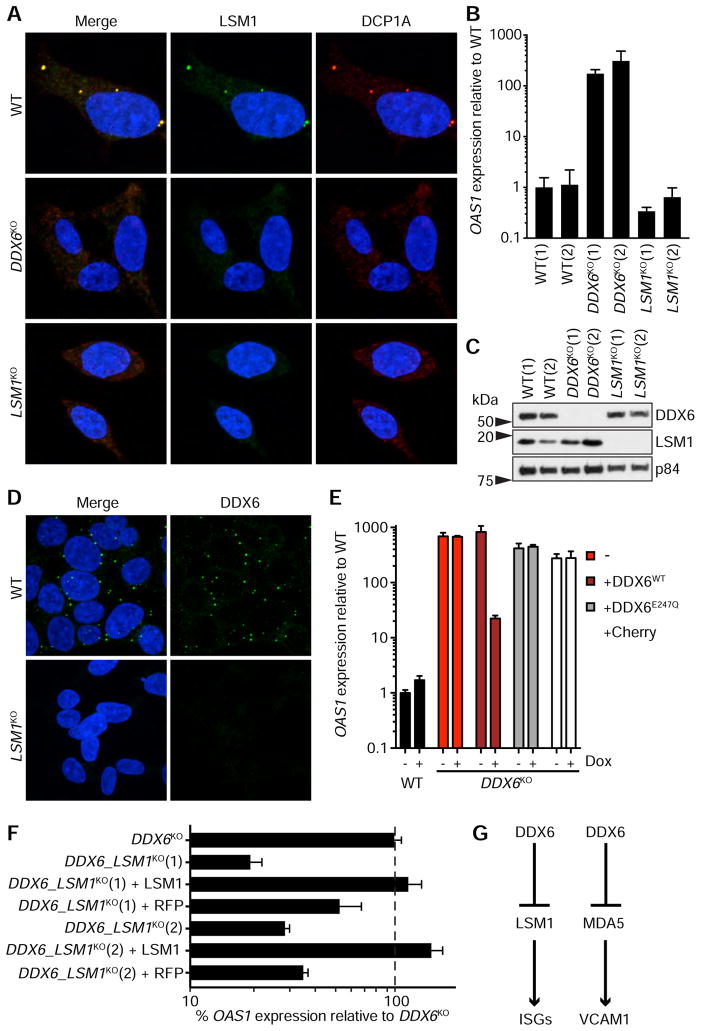

Figure 6. P-body disruption does not cause ISG upregulation and DDX6 represses ISG activation via LSM1.

(A) Localization of LSM1 and DCP1A in WT, DDX6KO and LSM1KO HAP1 cells. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) qPCR of OAS1 in WT, DDX6KO and LSM1KO. Two unique clones for each genotype are shown by (1) and (2). Data are mean ± SEM of three independent RNA extractions. (C) Protein expression of DDX6 and LSM1 in WT, DDX6KO and LSM1KO cells. For each genotype, two unique clonal cell lines are shown by (1) and (2). (D) Localization of DDX6 in WT or LSM1KO HAP1 cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) qPCR analysis of OAS1 in WT cells and DDX6KO cells complemented with wild-type DDX6 (+DDX6WT), ATPase-deficient DDX6 (+DDX6E247Q) or a vector control expressing Cherry (+Cherry). – denotes uncomplemented DDX6KO cells. Dox, doxycycline. (F) qPCR of OAS1 in DDX6KO and two unique DDX6 LSM1 double knockout clones (DDX6_LSM1KO) denoted by (1) and (2) complemented with LSM1 or vector control expressing RFP. Data are mean ± SEM of n=18 (DDX6KO) or n=9 (all other cell lines), from 3 independent experiments. (G) Summary of genetic relationships discovered in this study.

To determine whether DDX6 helicase activity is required to prevent immune gene activation, we created a mutant with a single amino acid substitution (DDX6E247Q) in the DEAD box RNA helicase domain (DEAD to DQAD) (Mathys et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). Genetic complementation of DDX6E247Q in DDX6KO cells failed to rescue OAS1, IFITM1 or VCAM1 expression indicating that the catalytic activity of DDX6 is necessary to repress immune activation (Figures 6E and S6C–E).

DDX6 and LSM1 are decapping coactivators and act in concert to recruit the decapping machinery to RNA (Coller et al., 2001; Fischer and Weis, 2002; Tharun et al., 2000). Although these genes function in the same pathway and localize to the same structures, our data indicates that only DDX6 regulates ISG activation. To probe the relationship between DDX6 and LSM1 in the context of ISG repression, we generated a DDX6 LSM1 double knockout (DDX6_LSM1KO) (Figure S6F). Remarkably, deletion of LSM1 in DDX6KO cells rescued ISG expression (Figures 6F and S6G). ISG activation was restored in DDX6_LSM1KO cells by expressing LSM1 in trans, confirming that the rescue of ISG expression in DDX6_LSM1KO cells was due to loss of LSM1. Knockout of LSM1 in DDX6KO cells did reduce VCAM1 levels, but not as substantially as ISG expression (Figure S6H). These data reveal an unexpected synthetic interaction between DDX6 and LSM1 in preventing aberrant ISG activation (Figure 6G).

DISCUSSION

Although basal IFN expression plays a critical role in maintaining homeostasis in healthy tissues, aberrant activation of immune genes can cause autoimmunity and dysregulated antiviral responses. However, our understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing basal ISG expression, and how signaling perturbations cause disease, remains incomplete.

We identified genes that regulate basal ISG expression under sterile conditions by performing an unbiased, genome-wide genetic screen. Our data identify a function for DDX6 in preventing the aberrant activation of an immune state. Transcriptional profiling revealed that DDX6 regulates genes of the adaptive immune response and ISGs, indicating a broad impact on immunity. We show that in transformed and primary human cells DDX6 represses ISGs through a STAT1-independent, cell intrinsic mechanism. We genetically define a pathway linking MDA5 and LSM1 to aberrant immune gene expression in DDX6KO cells. DDX6 represents the latest addition to a growing number of DExD/H helicases that have become recognized as key mediators of the antiviral response. Of this family, DDX6 is unique from other DExD/H helicases employed to regulate the antiviral response in its singular ability to negatively regulate immunity.

It is becoming increasingly clear that aberrant nucleic acid metabolism can contribute to autoimmunity. Mutations in TREX1, a 3′–5′ exonuclease that degrades cytosolic DNA, cause Aicardi-Goutières syndrome and chilblain lupus. Deletion of the TREX1 causes the accumulation of endogenous nucleic acids, triggering cell intrinsic autoimmunity via the DNA sensor cGAS (Ablasser et al., 2014; Gray et al., 2015; Stetson et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2007). In addition, mutations in SKIV2L trigger MAVS-dependent ISG upregulation by generating endogenous RNA ligands (Eckard et al., 2014). SKIV2L is part of the cytosolic RNA exosome responsible for directing 3′-5′ degradation of cellular mRNAs. Through a genome-scale analysis we now show that deletion of DDX6 results in ISG upregulation. DDX6 plays a critical role in decapping mRNAs that have been targeted for degradation by the shortening of their 3′-poly(A) tails. This enables DDX6 to mediate cytoplasmic mRNA turnover. Given the essential function of decapping in the degradation of mRNAs in the 5′ to 3′ direction, we propose that DDX6 deletion perturbs mRNA turnover, resulting in ISG and immune gene activation–potentially due to the accumulation of endogenous aberrant RNA ligands. The involvement of the 5′ to 3′ degradation machinery in ISG suppression by DDX6 is underscored by our discovery of a genetic relationship between DDX6 and LSM1–a protein which decaps the 5′ end and protects the 3′ end from degradation by the RNA exosome (He and Parker, 2001; Tharun et al., 2000, 2005)

In addition to classic ISGs, we found that specific proinflammatory cytokines such as VCAM1 were also upregulated, suggesting that DDX6 regulates multiple transcriptional pathways. Deletion of the cytosolic dsRNA sensor MDA5 rescued VCAM1 levels in DDX6KO cells, indicating that DDX6 limits MDA5 activation to prevent VCAM1 release. While our data suggests that DDX6 prevents immunostimulatory RNA accumulation, the identities and origin(s) of the RNA species remains unknown. Upon MDA5 ligation the NF-κB pathway can be triggered by MAVS activation. Indeed, VCAM1 contains NF-κ B binding sites, implicating the NF-κB pathway in proinflammatory cytokine release in DDX6 knockouts (Shu et al., 1993). Surprisingly, we observed VCAM1 upregulation in DDX6KO cells independent of MAVS, the canonical downstream activator of MDA5. MAVS-independent SINE RNA activation of NF-κB has been observed in murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection pointing to the existence of MAVS-independent RNA sensing pathways (Karijolich et al., 2015). Using OAS1 and IFITM1 as markers for ISG activation, we found that deletion of RIG-I, MDA5, PKR and MAVS did not restore ISG levels to WT. This indicates that DDX6 deletion may trigger parallel RNA sensing pathways or that ISGs might be activated independently of the canonical RNA sensors and adaptors.

We demonstrate that depletion of DDX6 results in broad cell-intrinsic activation of ISGs without concurrent IFN production. This constitutive ISG activation leads to enhanced responsiveness to exogenous IFN, because components of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway are themselves ISGs. Furthermore, because many ISGs are directly antiviral and because RNA sensors are ISGs, DDX6 deletion imposed an antiviral state against a broad range of RNA viruses from different families. Intriguingly, independent from our newly discovered role of DDX6 in ISG repression, DDX6 has been implicated in the life cycle of several RNA viruses. For example, in insect cells that lack IFN signaling, DDX6 restricts bunyaviral replication by subverting the “cap-snatching” mechanism that negative stranded viruses use to express their genome (Hopkins et al., 2013). In addition, DDX6 plays an essential role in replicating the positive-stranded plant RNA virus Brome Mosaic virus (BMV) in yeast cells. DDX6 is necessary for efficient viral translation and for the transition from translation to replication (Mas et al., 2006). Both viruses replicate in organisms lacking a functional IFN response, highlighting that RNA viruses can be restricted by components of the cellular mRNA pathway (bunyaviruses) or can hijack these components to facilitate replication (BMV). Evidently DDX6 can be antiviral or proviral depending on the particular viral infection, even in cells lacking an IFN response. Moreover, in mammalian cells DDX6 facilitates hepatitis C virus (HCV), dengue virus (DENV) and Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV1) infection by stimulating translation and replication (HCV and DENV) or capsid assembly (HIV1) (Huys et al., 2013; Jangra et al., 2010; Nathans et al., 2009; Pager et al., 2013; Reed et al., 2012; Scheller et al., 2009; Ward et al., 2011). In our study, we found broad antiviral effects and potent ISG activation upon DDX6 deletion, however we cannot exclude the possibility that diminished replication was due to a proviral function of DDX6 for some of the viruses. Our discovery that DDX6 suppresses ISG activation raises the possibility that the interaction of viruses with DDX6 might serve as trigger for the host to switch on an antiviral defense mechanism. This possibility is all the more intriguing given that DDX6 depletion bypasses the canonical MAVS-mediated RNA sensing pathway.

Clearly DDX6 plays a multifaceted role in immunity. It is hijacked by viruses and has provirus functions, but simultaneously prevents the spontaneous activation of immune genes. DDX6 mutants are characterized by constitutive ISG expression and elevated VCAM1 secretion. VCAM1 mediates leukocyte emigration, contributing to chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (Okamoto et al., 2008). In fact, VCAM1 secretion is superior to conventional biomarkers for monitoring disease progression of lupus (Lewis et al., 2016). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) near DDX6 have been linked to multiple autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus (Zhang et al., 2014; Zhernakova et al., 2011). In conjunction with our data, this provides evidence for a potential role of DDX6 in repressing autoimmunity. Our findings hint at the exciting possibility of a previously unknown mechanism for the pathogenesis of certain autoimmune diseases characterized by SNPs near DDX6. At the organismal level, overexpressing DDX6 had profound consequences on fertility and birth rates in mice (Matsumoto et al., 2005). Like SKIV2L and TREX1, DDX6 may provide a threshold-setting mechanism for cytosolic nucleic acid sensors. Moving forward, the link between DDX6 expression and ISG activation may be explored by engineering human cells with SNPs near DDX6 that have been associated with autoimmunity.

Experimental procedures

Haploid genetic screens

The haploid genetic screen was performed similarly to the protocol described with minor changes (Carette et al., 2011b). HAP1 cells were transduced with the vector 5xISRE-eGFP to create an ISG reporter cell line. The reporter cell line was sensitized to IFNλby overexpressing IFNLR1. These cells were then sub-cloned to obtain a clonal population prior to mutagenesis. An RFP-gene trap virus was used to create a mutagenized HAP1 reporter library. 100 million mutagenized cells were stimulated with 10 IU/ml IFNλ2. After 24 h, stimulated cells were sorted for GFP-negative cells (approximately 5% of the population) and grown for 3 days. The cells were stimulated again with 10 IU/ml IFNλ2 for 24 h and sorted on GFP-negative cells to enrich for cells that no longer responded to IFN treatment. Thirty million cells of the selected population were used for genomic DNA isolation. To sort for cells that displayed constitutive activation of the reporter in the absence of IFN, 100 million mutagenized, unstimulated, cells were sorted for the top 5% GFP positive by FACS and grown over a period of 4 days. Cells were then re-sorted for the top 5% GFP positive to enrich for cells displaying constitutive reporter activation. Gene trap insertion sites were determined by linear amplification of the genomic DNA (gDNA) flanking regions of the gene trap DNA insertion sites and sequenced on a Genome Analyzer II. Reads were aligned to the human genome using Bowtie and enrichment of independent insertions was calculated as previously described.

Genome engineering

CRISPR guide RNA (gRNA) sequences were designed using the CRISPR design tool (crispr.mit.edu). Oligos corresponding to the gRNA sequences in Table 1 were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies) and cloned into the pX458 gRNA plasmid (Addgene 48138). HuH7 and NHDF cells were transfected with pX458 using lipofectamine 3000 (Life technologies). HAP1 cells were electroporated using the Amaxa nucleofactor (Lonza). After 48 h, GFP-expressing cells were subcloned using a BD InFlux Cell Sorter at the Stanford Shared FACS facility. For NHDF knockout generation, cells were transfected with pX458 in addition to a vector containing a gRNA to the zebrafish TIA gene and a cassette of a 2A sequence followed by blasticidin, flanked by two TIA target sites (a kind gift of T. Brummelkamp) (Blomen et al., 2015). This allowed for blasticidin screening-based selection of edited clones. Clonal cell lines were allowed to expand and gDNA was isolated for sequenced based genotyping of the targeted allele. In HAP1, only one mutated allele was present in the sequenced PCR product. In aneuploid HuH7 cells, we observed that the PCR product contained more than 1 trace, suggesting non-identical mutations in multiple alleles. In this case, the PCR product was cloned into a plasmid vector and colonies were sequenced to separate allele specific mutations. Subclones were chosen where all alleles were mutated.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Cells were plated in 96 wells and cDNA prepared using Power SYBR Green Cells-to-CT kit (Ambion 4402954) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. GAPDH or 18S was used to normalize for mRNA input. All data presented is representative of at least two independent experiments, performed on RNA from three independent extractions. To plot relative expression when multiple knockout clones were used, one wild type (WT) clone was arbitrarily set at 1.

Cell tracker assay

Cells were loaded with 10 μM CFSE in the absence of serum for 10 min at 37°C. After washing in PBS, unloaded and loaded cells were mixed in equal ratios and co-cultured for 48 h. Cells were sorted for the presence or absence of CFSE by FACS. RNA was extracted from the sorted populations as described under Quantitative real-time PCR.

Cytokine secretion analysis

Cells were plated in 24 well and cultured for 48 h. Supernatants were harvested and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min at 4°C to remove cells. Luminex was performed on supernatants in 63-plex by the Stanford Human Immune Monitoring Center to determine cytokine concentrations. To determine cytokine levels from infected cells, cells were plated 24 h prior to infection. Cells were infected with influenza at an MOI of 0.1 for 8 h. Cells were then washed and fresh medium added before harvesting as above 24 h after media change.

Genetic complementation of DDX6 knockouts with DDX6

Cells were plated in 6 wells and treated with doxycycline (250 ng/ml) for 5 days. Doxycycline was replenished every 48 h and cells passaged as necessary. After 5 days, cells were harvested for immunoblot and plated for qPCR experiments.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed at the Stanford Shared FACS facility. To perform the haploid genetic screens, FACS was carried out on a BD FACS Aria flow-cytometer (BD biosciences). To measure virus reporter expression, infected cells were trypsinized, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at RT, washed and then analyzed for GFP expression on a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD biosciences). For cell surface staining, cells were dissociated using 1mM EDTA in 1x PBS (calcium and magnesium free) and washed using FACS buffer (1×PBS supplemented with 2% FCS, 1mM EDTA and 0.1% sodium azide) at 4°C. Cells were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with PE conjugated an ti-human VCAM1 antibody (Biolegend). Cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer before reading fluorescence. IFITM1 surface staining was performed by incubating cells with anti-human IFITM1 for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed and incubated for 30 min at 4°C with anti-rabbit Alexa488-conjugated sec ondary antibody (1:500 dilution) (Life Technologies). Cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer before reading fluorescence. All data presented is representative of at least two independent experiments. Data was analyzed and assembled using FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc).

Viral infections

HuH7 cells were plated overnight at in 24 wells with 0, 2, 20 or 200 IU/ml IFNα2a. The next day cells were infected with VEEV-GFP (MOI of 3 for 5.5 h), DENV-GFP (MOI of 0.02 for 48 h) or VSV-GFP (MOI of 0.01 for 11 h). Infected cells were harvested for flow cytometry at the indicated time points. The experiment was performed three times, in triplicate and a representative is shown. HuH7 were plated overnight at in 96 wells with 0, 2, 20 or 200 IU/ml IFNα2a and infected the next day with MENGV (MOI of 0.01). After 18 h infected cells were harvested for qPCR as described. HAP1 cells were plated in 96 wells and infected at an MOI of 0.01 with Sendai virus and Influenza PR8. Cells were harvested for qPCR after 18 h. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate and a representative is shown.

Luciferase reporter virus assays

HAP1 cells were plated in triplicate and infected with dengue luciferase reporter virus at an MOI of 0.01. Cell lysates were collected at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post-infection. Luciferase expression was measured using Renilla Luciferase Assay system (Promega E2820). Cells were lysed using Renilla lysis buffer and luciferase activity measured by addition of substrate and readings taken using Glomax 20/20 luminometer with a 10-s integration time.

RNA-sequencing

Total RNA was prepared from two independently generated knockout and WT clonal cell lines. TruSeq kit (illumina) was used to generate libraries in technical replicate for RNA sequencing by the Stanford functional genomics facility. Sequencing data was analyzed as described under supplemental experimental procedures.

STATS

The unpaired parametric two-sided Student’s t-test was used for statistical calculations involving two group comparisons in all tissue-culture-based experiments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). GraphPad Prism was used for statistical calculations.

Additional experimental methods are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Related to figure S1. Screen results for positive regulators of IFNλ signaling.

Table S2. Related to figure 1. Screen results for genes that prevent activation of ISGs in the absence of IFN

Table S3. Related to figure 2. Gene expression profiles of DDX6KO cells

Table S4. Related to figure 2. Unbiased pathway analysis of genes upregulated in DDX6KO cells

Table S5. Related to figure S2. Genes in GO term GO:0060337

Table S6. Related to figure S2. Gene expression profile of USP14KO cells

Highlights.

Unbiased screen identifies DDX6 RNA helicase as suppressor of ISG activation

Depleting DDX6 in human cells activates cell intrinsic immunity

DDX6 deletion induces an antiviral state, causing resistance to RNA viruses

DDX6 suppresses ISGs via LSM1, a core component of the RNA degradation machinery

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) DP2 AI104557 (J.E.C.), David and Lucile Packard Foundation (J.E.C.), Stanford University Dean’s postdoctoral award (J.H.L.) and the Child Health Research Institute Grant and Postdoctoral Award (J.H.L.). We thank Horizon genomics for providing cell lines. We thank X. Ji and the Stanford Functional Genomics Facility and the Stanford Shared FACS Facility. We thank Dan Lichterman for editing the manuscript, Cole Dovey and Denise Monack for reading the manuscript, and all members of the Carette lab for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.H.L and J.E.C designed the research and wrote the manuscript. J.H.L performed the majority of the experiments. Q.L and J.B.L analyzed RNA-seq data. L.M.P generated immunofluorescence data. M.L created USP14KO cell lines. B.D.M made the DDX6E247Q construct. S.D performed P-IRF3, IFNAR1 and MDA5 immunoblots under supervision of H.B.G.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

RNA-seq data have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database at EMBL-EBI (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession numbers E-MTAB-5865 (USP14) and E-MTAB-5867 (DDX6). Sequencing data for the haploid genetic screens have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database under the accession number E-MTAB-5866.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ablasser A, Hemmerling I, Schmid-Burgk JL, Behrendt R, Roers A, Hornung V. TREX1 Deficiency Triggers Cell-Autonomous Immunity in a cGAS-Dependent Manner. J Immunol. 2014;192:5993–5997. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrei MA, Ingelfinger D, Heintzmann R, Achsel T, Rivera-Pomar R, Lührmann R. A role for eIF4E and eIF4E-transporter in targeting mRNPs to mammalian processing bodies. RNA. 2005;11:717–727. doi: 10.1261/rna.2340405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayache J, Bénard M, Ernoult-Lange M, Minshall N, Standart N, Kress M, Weil D. P-body assembly requires DDX6 repression complexes rather than decay or Ataxin2/2L complexes. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:2579–2595. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-03-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu M, Maitra RK, Xiang Y, Meng X, Banerjee AK, Bose S. Inhibition of vesicular stomatitis virus infection in epithelial cells by alpha interferon-induced soluble secreted proteins. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2653–2662. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomen VA, Májek P, Jae LT, Bigenzahn JW, Nieuwenhuis J, Staring J, Sacco R, van Diemen FR, Olk N, Stukalov A, et al. Gene essentiality and synthetic lethality in haploid human cells. Science. 2015;350:1092–1096. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette JE, Guimaraes CP, Varadarajan M, Park AS, Wuethrich I, Godarova A, Kotecki M, Cochran BH, Spooner E, Ploegh HL, et al. Haploid genetic screens in human cells identify host factors used by pathogens. Science. 2009;326:1231–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1178955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette JE, Guimaraes CP, Wuethrich I, Blomen VA, Varadarajan M, Sun C, Bell G, Yuan B, Muellner MK, Nijman SM, et al. Global gene disruption in human cells to assign genes to phenotypes by deep sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2011a;29:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette JE, Raaben M, Wong AC, Herbert AS, Obernosterer G, Mulherkar N, Kuehne AI, Kranzusch PJ, Griffin AM, Ruthel G, et al. Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1. Nature. 2011b;477:340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Meng Q, Qin Y, Liang P, Tan P, He L, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Huang J, Wang RF, et al. TRIM14 Inhibits cGAS Degradation Mediated by Selective Autophagy Receptor p62 to Promote Innate Immune Responses. Mol Cell. 2016;64:105–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Rana TM. Translation Repression in Human Cells by MicroRNA-Induced Gene Silencing Requires RCK/p54. PLOS Biol. 2006;4:e210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller JM, Tucker M, Sheth U, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Parker R. The DEAD box helicase, Dhh1p, functions in mRNA decapping and interacts with both the decapping and deadenylase complexes. RNA. 2001;7:1717–1727. doi: 10.1017/s135583820101994x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrales L, Matson V, Flood B, Spranger S, Gajewski TF. Innate immune signaling and regulation in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2017;27:96–108. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow YJ, Manel N. Aicardi-Goutières syndrome and the type I interferonopathies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:429–440. doi: 10.1038/nri3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowl JT, Gray EE, Pestal K, Volkman HE, Stetson DB. Intracellular Nucleic Acid Detection in Autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson S, Crotta S, McCabe TM, Wack A. Pathogenic potential of interferon αβ in acute influenza infection. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3864. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckard SC, Rice GI, Fabre A, Badens C, Gray EE, Hartley JL, Crow YJ, Stetson DB. The SKIV2L RNA exosome limits activation of the RIG-I-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:839–845. doi: 10.1038/ni.2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer N, Weis K. The DEAD box protein Dhh1 stimulates the decapping enzyme Dcp1. EMBO J. 2002;21:2788–2797. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullam A, Schröder M. DExD/H-box RNA helicases as mediators of anti-viral innate immunity and essential host factors for viral replication. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:854–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gack MU, Diamond MS. Innate immune escape by Dengue and West Nile viruses. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;20:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauntt CJ, Lockart RZ. Inhibition of Mengo virus by interferon. J Bacteriol. 1966;91:176–182. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.1.176-182.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough DJ, Messina NL, Clarke CJP, Johnstone RW, Levy DE. Constitutive type I interferon modulates homeostatic balance through tonic signaling. Immunity. 2012;36:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EE, Treuting PM, Woodward JJ, Stetson DB. Cutting Edge: cGAS Is Required for Lethal Autoimmune Disease in the Trex1-Deficient Mouse Model of Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 2015;195:1939–1943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieder FB, Vogel SN. Role of interferon and interferon regulatory factors in early protection against Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus infection. Virology. 1999;257:106–118. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata N, Sato M, Takaoka A, Asagiri M, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T. Constitutive IFN-alpha/beta signal for efficient IFN-alpha/beta gene induction by virus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:518–525. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Parker R. The Yeast Cytoplasmic LsmI/Pat1p Complex Protects mRNA 3′ Termini From Partial Degradation. Genetics. 2001;158:1445–1455. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.4.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton SM, Borg NA, Dixit VM. Ubiquitin in the activation and attenuation of innate antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2016;213:1–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho LJ, Hung LF, Weng CY, Wu WL, Chou P, Lin YL, Chang DM, Tai TY, Lai JH. Dengue virus type 2 antagonizes IFN-alpha but not IFN-gamma antiviral effect via down-regulating Tyk2-STAT signaling in the human dendritic cell. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 2005;174:8163–8172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins KC, McLane LM, Maqbool T, Panda D, Gordesky-Gold B, Cherry S. A genome-wide RNAi screen reveals that mRNA decapping restricts bunyaviral replication by limiting the pools of Dcp2-accessible targets for cap-snatching. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1511–1525. doi: 10.1101/gad.215384.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huys A, Thibault PA, Wilson JA. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA accumulation and translation by DDX6 and miR-122 are mediated by separate mechanisms. PloS One. 2013;8:e67437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A. A Virological View of Innate Immune Recognition. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:177–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jangra RK, Yi M, Lemon SM. DDX6 (Rck/p54) is required for efficient hepatitis C virus replication but not for internal ribosome entry site-directed translation. J Virol. 2010;84:6810–6824. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00397-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karijolich J, Abernathy E, Glaunsinger BA. Infection-Induced Retrotransposon-Derived Noncoding RNAs Enhance Herpesviral Gene Expression via the NF-κB Pathway. PLOS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005260. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Larner A, Chaudhuri A, Babiss LE, Darnell JE. Interferon-stimulated transcription: isolation of an inducible gene and identification of its regulatory region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:8929–8933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.8929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MJ, Vyse S, Shields AM, Zou L, Khamashta M, Gordon PA, Pitzalis C, Vyse TJ, D’Cruz DP. Improved monitoring of clinical response in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus by longitudinal trend in soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:5. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0896-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienenklaus S, Cornitescu M, Zietara N, Łyszkiewicz M, Gekara N, Jabłónska J, Edenhofer F, Rajewsky K, Bruder D, Hafner M, et al. Novel reporter mouse reveals constitutive and inflammatory expression of IFN-beta in vivo. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 2009;183:3229–3236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas A, Alves-Rodrigues I, Noueiry A, Ahlquist P, Díez J. Host deadenylation-dependent mRNA decapping factors are required for a key step in brome mosaic virus RNA replication. J Virol. 2006;80:246–251. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.246-251.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathys H, Basquin J, Ozgur S, Czarnocki-Cieciura M, Bonneau F, Aartse A, Dziembowski A, Nowotny M, Conti E, Filipowicz W. Structural and biochemical insights to the role of the CCR4-NOT complex and DDX6 ATPase in microRNA repression. Mol Cell. 2014;54:751–765. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Kwon OY, Kim H, Akao Y. Expression of rck/p54, a DEAD-box RNA helicase, in gametogenesis and early embryogenesis of mice. Dev Dyn Off Publ Am Assoc Anat. 2005;233:1149–1156. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathans R, Chu CY, Serquina AK, Lu CC, Cao H, Rana TM. Cellular microRNA and P bodies modulate host-HIV-1 interactions. Mol Cell. 2009;34:696–709. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H, Hoshi D, Kiire A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N. Molecular targets of rheumatoid arthritis. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2008;7:53–66. doi: 10.2174/187152808784165199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostareck DH, Naarmann-de Vries IS, Ostareck-Lederer A. DDX6 and its orthologs as modulators of cellular and viral RNA expression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2014;5:659–678. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pager CT, Schütz S, Abraham TM, Luo G, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance and virus release by dispersion of processing bodies and enrichment of stress granules. Virology. 2013;435:472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puschnik AS, Majzoub K, Ooi YS, Carette JE. A CRISPR toolbox to study virus-host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:351–364. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pylaeva E, Lang S, Jablonska J. The Essential Role of Type I Interferons in Differentiation and Activation of Tumor-Associated Neutrophils. Front Immunol. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC, Molter B, Geary CD, McNevin J, McElrath J, Giri S, Klein KC, Lingappa JR. HIV-1 Gag co-opts a cellular complex containing DDX6, a helicase that facilitates capsid assembly. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:439–456. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller N, Mina LB, Galão RP, Chari A, Giménez-Barcons M, Noueiry A, Fischer U, Meyerhans A, Díez J. Translation and replication of hepatitis C virus genomic RNA depends on ancient cellular proteins that control mRNA fates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13517–13522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906413106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu HB, Agranoff AB, Nabel EG, Leung K, Duckett CS, Neish AS, Collins T, Nabel GJ. Differential regulation of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 gene expression by specific NF-kappa B subunits in endothelial and epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6283–6289. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson DB, Ko JS, Heidmann T, Medzhitov R. Trex1 Prevents Cell-Intrinsic Initiation of Autoimmunity. Cell. 2008;134:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharun S, He W, Mayes AE, Lennertz P, Beggs JD, Parker R. Yeast Sm-like proteins function in mRNA decapping and decay. Nature. 2000;404:515–518. doi: 10.1038/35006676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharun S, Muhlrad D, Chowdhury A, Parker R. Mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae LSM1 gene that affect mRNA decapping and 3′ end protection. Genetics. 2005;170:33–46. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wack A, Terczyńska-Dyla E, Hartmann R. Guarding the frontiers: the biology of type III interferons. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:802–809. doi: 10.1038/ni.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Arribas-Layton M, Chen Y, Lykke-Andersen J, Sen GL. DDX6 Orchestrates Mammalian Progenitor Function through the mRNA Degradation and Translation Pathways. Mol Cell. 2015;60:118–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward AM, Bidet K, Yinglin A, Ler SG, Hogue K, Blackstock W, Gunaratne J, Garcia-Blanco MA. Quantitative mass spectrometry of DENV-2 RNA-interacting proteins reveals that the DEAD-box RNA helicase DDX6 binds the DB1 and DB2 3′ UTR structures. RNA Biol. 2011;8:1173–1186. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.6.17836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wathelet MG, Berr PM, Huez GA. Regulation of gene expression by cytokines and virus in human cells lacking the type-I interferon locus. Eur J Biochem. 1992;206:901–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson EB, Yamada DH, Elsaesser H, Herskovitz J, Deng J, Cheng G, Aronow BJ, Karp CL, Brooks DG. Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science. 2013;340:202–207. doi: 10.1126/science.1235208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YG, Lindahl T, Barnes DE. Trex1 exonuclease degrades ssDNA to prevent chronic checkpoint activation and autoimmune disease. Cell. 2007;131:873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang Y, Yang J, Zhang L, Sun L, Pan HF, Hirankarn N, Ying D, Zeng S, Lee TL, et al. Three SNPs in chromosome 11q23.3 are independently associated with systemic lupus erythematosus in Asians. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:524–533. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhernakova A, Stahl EA, Trynka G, Raychaudhuri S, Festen EA, Franke L, Westra HJ, Fehrmann RSN, Kurreeman FAS, Thomson B, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis identifies fourteen non-HLA shared loci. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Related to figure S1. Screen results for positive regulators of IFNλ signaling.

Table S2. Related to figure 1. Screen results for genes that prevent activation of ISGs in the absence of IFN

Table S3. Related to figure 2. Gene expression profiles of DDX6KO cells

Table S4. Related to figure 2. Unbiased pathway analysis of genes upregulated in DDX6KO cells

Table S5. Related to figure S2. Genes in GO term GO:0060337

Table S6. Related to figure S2. Gene expression profile of USP14KO cells