Abstract

The glutamatergic system has an important role in cocaine-seeking behavior. Studies have reported that chronic exposure to cocaine induces downregulation of glutamate transporter-1 (GLT-1) and cystine/glutamate exchanger (xCT) in the central reward brain regions. Ceftriaxone, a β-lactam antibiotic, restored GLT-1 expression and consequently reduced cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. In this study, we investigated the reinstatement to cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) seeking behavior using a conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm in male alcohol-preferring (P) rats. In addition, we investigated the effects of Ampicillin/Sulbactam (AMP/SUL) (200 mg/kg, i.p.), a β-lactam antibiotic, on cocaine-induced reinstatement. We also investigated the effects of AMP/SUL on the expression of glial glutamate transporters and metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) core and shell and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC). We found that AMP/SUL treatment reduced cocaine-triggered reinstatement. This effect was associated with a decrease in locomotor activity. Moreover, GLT-1 and xCT were downregulated in the NAc core and shell, but not in the dmPFC, following cocaine-primed reinstatement. However, cocaine exposure increased the expression of mGluR1 in the NAc core, but not in the NAc shell or dmPFC. Importantly, AMP/SUL treatment normalized GLT-1 and xCT expression in the NAc core and shell; however, the drug normalized mGluR1 expression in the NAc core only. Additionally, AMP/SUL increased the expression of GLT-1 and xCT in the dmPFC as compared to the water naïve group. These findings demonstrated that glial glutamate transporters and mGluR1 in the mesocorticolimbic area could be potential therapeutic targets for the attenuation of reinstatement to cocaine-seeking behavior.

Keywords: GLT-1, xCT, Cocaine, mGluR1, CPP, Locomotor activity

1. INTRODUCTION

Glutamatergic neurotransmission within the mesocorticolimbic circuit plays a major role in reinstatement to cocaine-seeking behavior in rat models (1, 2). Cocaine has an indirect effect on the elevation of extracellular glutamate concentrations in the limbic system, particularly in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), which can lead to neuroplastic changes including alteration in the expression of glutamatergic receptors in the central nervous system (3–5). Ample evidence linked the glutamatergic system and cues-, stress-, and drug-primed reinstatement of cocaine seeking [For review see (6)]. Cocaine-seeking behavior was blocked following microinjection of ionotropic glutamatergic receptor antagonist within the NAc (7, 8). Importantly, foot shock-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior was initiated through glutamatergic projections to the NAc (9). This suggests the key role in the maintenance of cocaine-seeking behavior.

Astrocytes are the most abundant glial cells in the brain, constituting of 40–50% of all glial cells, with several key functions (10). Importantly, astrocytes have been shown to control the clearance of extracellular glutamate concentrations in the brain [For review see (11)]. This clearance is regulated by a family of glutamate transporters, in particular, glial glutamate transporter type 1 (GLT-1), which is responsible for clearing the majority of extracellular glutamate concentration (12). Studies have shown that cocaine exposure reduced GLT-1 expression in the NAc (13). Cystine/glutamate transporter (xCT) is another glial glutamate transporter that exchanges extracellular cystine by intracellular glutamate. This transporter was also downregulated in the NAc in the reinstatement to cocaine seeking in animal model (13) and in animals chronically exposed to cocaine (14, 15). Glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST) is another glial transporter that is responsible for regulating glutamate homeostasis (16). In this study, we investigated the effects of non-contingent cocaine reinstatement in a conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm on the expression of these glial glutamate transporters in the NAc core and shell as well as the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC).

β-lactam antibiotics are known to upregulate GLT-1 expression in the brain (17, 18). We and others have shown that ceftriaxone, β-lactam antibiotic, attenuated relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior in part through upregulation of GLT-1 and xCT expression in the NAc and PFC (13, 19). Furthermore, ampicillin (AMP), a β-lactam antibiotic, upregulated GLT-1 and xCT expression in the NAc and PFC, and decreased daily ethanol intake (20, 21). In this study, we used CPP as a model to study relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior, since this testing paradigm is considered as a valid method to investigate relapse to drug-seeking behavior in laboratory animals (22–24). Thus, we investigated for the first time the effects of AMP and sulbactam (SUL) on reinstatement to cocaine-seeking behavior and locomotor activity using this CPP paradigm.

In this study, we also determined the expression of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1), which is expressed in the mesocorticolimbic areas (25–27). Studies revealed that treatment with selective mGluR1 antagonists reduced cocaine-seeking behavior in monkeys (28), and reduced psychomotor sensitization in rodents (29, 30). In addition, a study showed that mGluR1 antagonist blocked cocaine-induced CPP (31). In addition to glial glutamate transporters, we focused this study on the effect of cocaine-induced reinstatement as well as AMP/SUL treatment on mGluR1 expression in the NAc (core and shell) and dmPFC.

Findings have proven that the NAc is a key brain region that regulates emotional and motivational responses, including reward-related activities and drug-seeking behavior (32). Importantly, cocaine exposure altered glutamate and dopamine neurotransmission in the sub-regions of the NAc (core and shell). The intra-injections of drugs of abuse, including cocaine, directly in the NAc shell, have been found to play a role in the development of conditioned reinforcement (33, 34) and motor response to dependence drugs (35, 36). However, the NAc core has been found to mediate cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior (33, 37–39).

Furthermore, the PFC has been suggested to be implicated in drug-seeking behavior (40). Enhancing glutamatergic function in the dmPFC projections to the NAc core and shell is necessary for the modulation of cocaine-seeking behavior (1, 2, 9, 41). Moreover, glutamate projections from the dmPFC to the NAc core regulate non-contingent cocaine-induced reinstatement in rats exposed to cocaine (42, 43) and cues (44, 45). It is important to note that dysregulation in the glutamate homeostasis can lead to methamphetamine-, morphine- and cocaine-seeking behavior as well as facilitation of relapse to drug-seeking behaviors (13, 46–48). In particular, exposure to cocaine was associated with an increase in extracellular glutamate concentrations in the NAc (49).

Neural interconnection analysis has identified two sub-circuits within the mesocorticolimbic pathway. One circuit includes the glutamatergic projection from the ventral PFC (vPFC) and the infralimbic structure into the NAc shell, and the second circuit comprises the dmPFC and NAc core, which connect with the motor system [For review see (50, 51)]. Previous studies revealed the involvement of the limbic circuit with behavioral changes that are associated with chronic drug use, including relapse (52, 53). In addition, evidence showed neuroadaptation in the limbic circuit following repeated exposure to drugs of abuse (54, 55). However, behavioral changes associated with chronic drug use are often defined as compulsive or automatic, which may indicate the activation of the motor circuit more than the limbic (56, 57). Importantly, different stimuli may trigger chronic drug-abuse related behavior, including craving, via the limbic circuit, but the execution of the behavior may depend on the motor circuit (42).

In the present study, we investigated the effects of cocaine reinstatement on GLT-1, xCT, GLAST and mGluR1 in the NAc core, NAc shell and dmPFC of male alcohol-preferring (P) rats. The rationale for using P rats is that these rats are sensitive to the reinforcing effects of cocaine self-administration as compared to low alcohol-consuming rats (58). In addition, P rats were used as an extension of a previous work from our lab that studied the effects of chronic co-exposure of ethanol and cocaine on glial glutamate transporters and ethanol intake (59). Moreover, our study provides evidence of cocaine dependence in male P rats.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Subjects

Twenty-five male P rats were received from Indiana University, School of Medicine (Indianapolis, IN, USA) at the age of 21–30 days, and were housed in the Department of Laboratory Animal Resources, University of Toledo, Health Science Campus. At the age of 75 days, each rat was kept separately in a standard plastic cage and had a free access to food and water ad lib throughout the experiment. The room temperature was maintained at 21°C and 50% humidity with a 12-hour light-dark cycle. The experiments and housing procedures were in compliance with and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use committee of The University of Toledo, in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institutes of Health and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2 Conditioned place preference and locomotor activity

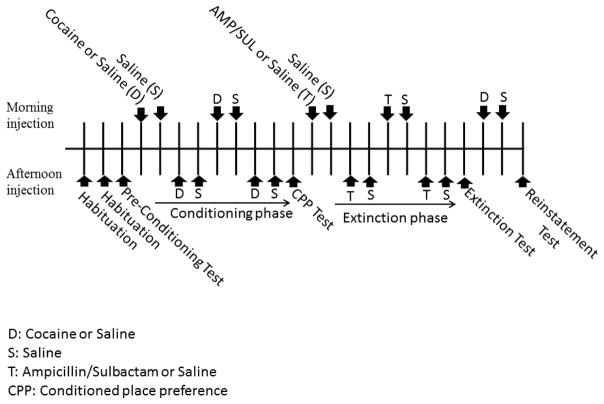

The experimental schedule is illustrated in Fig. 1, and the injections given to each experimental group are illustrated in Table 1 (60, 61). At the beginning of the experiment, rats were grouped into four groups: 1) Control group rats were given saline interaperitoneal (i.p.) injections throughout the experiment; 2) AMP/SUL group rats were conditioned with AMP/SUL (200 mg/kg, i.p.) only; 3) Cocaine-saline group rats were conditioned with cocaine and then given saline i.p. injections throughout the extinction phase, before being challenged with cocaine in the reinstatement phase; and 4) Cocaine-AMP/SUL group, rats were conditioned with cocaine followed by AMP/SUL i.p. injection in the extinction phase and challenged by cocaine injection in the reinstatement phase. In addition, two groups were i.p. injected with AMP/SUL or saline to investigate whether AMP/SUL induces any CPP preference or locomotion activity in water naïve rats. A full description of the experiment design is stated below.

Figure 1.

Experimental timeline for cocaine-conditioned place preference paradigm (CPP, Conditioned place preference; S, Saline; D, Cocaine or saline; T, Ampicillin/Sulbactam or saline).

Table 1.

Experimental groups and injections given in each phase

| Group | Conditioning | Extinction | Reinstatement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | |||

| Control group | Saline | Saline | Saline |

| AMP/SUL group | AMP/SUL or Saline | - | - |

| Cocaine- Saline group | Cocaine or Saline | Saline | Cocaine or Saline |

| Cocaine- AMP/SUL group | Cocaine or Saline | AMP/SUL or Saline | Cocaine or Saline |

2.2.1 Pre-conditioning test of CPP and locomotor activity

In this study, we used a rectangular Plexiglas box (110 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm) divided into three distinct chambers (white, black and colorless) by two guillotine doors. The similar size black and white compartments (40 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm) were used for conditioning, while the colorless compartment (30 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm) joining them together was designated as the middle compartment. The two conditioning chambers had different visual cues and floor textures: the inner walls of the white chamber had vertical black and white strips with a rough black floor, while the inner walls of the black chamber had horizontal white and black stripes with an even white floor. Rats were placed in the middle chamber for three minutes; afterward, the guillotine doors were removed and rats were allowed to roam freely in the CPP apparatus for 20 minutes on the first three days (habituation phase). On Day 3, a digital camera was situated above the apparatus, and time spent in each chamber was recorded and measured manually by an observer blinded to the experiment, defining the location of the head as the location of the rat (preconditioning test) as described previously (62). The recorded videos were analyzed to assess the locomotor activity using ANY-maze tracking software version 4.99m (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL). Rats were then randomly paired to each chamber in order to generate a similar average in time spent in each chamber (unbiased design).

2.2.2 Post-conditioning test and locomotor activity

2.2.2.1 Post-conditioning test of CPP and locomotor activity for cocaine or saline group

Over the next eight days, conditioning preference was monitored when alternating either i.p. injections of cocaine and saline or saline alone (conditioning phase). Cocaine hydrochloride (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis MO) was dissolved in saline (1 mg in 1 ml) and was prepared fresh every other day for i.p. injection at 20 mg/kg. On Days 1, 3, 5 and 7, rats were treated with either cocaine 20 mg/kg or saline (i.p. injections) and were instantly confined in their paired chamber for 30 minutes. On Days 2, 4, 6 and 8, rats were given saline and were confined in the opposite chamber for 30 minutes. The i.p. injections were given in a counterbalanced order. Specifically, injections on Days 1, 2, 5 and 6 were given in the mornings, while injections on Days 3, 4, 7 and 8 were administered in the afternoon. Also, the positioning of the chambers was changed every day, as described in a previous study (63). On Day 9, 48 hours after the last i.p. injection of cocaine, no injection was given, and CPP testing and locomotor activity, assessed as distance traveled, were conducted similarly to the preconditioning test described above.

2.2.2.2 Post-conditioning test of CPP and locomotor activity for AMP/SUL

A separate group of rats (n= 5) was conditioned in an identical manner to cocaine using AMP/SUL (Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC), which was dissolved in saline (1 mg in 1 ml) and prepared fresh every other day for i.p. injection at 200 mg/kg, as described in previous study using ceftriaxone (62). This experiment was conducted to observe the effects of AMP/SUL on CPP behavior and locomotor activity. CPP test and locomotor activity were performed as described above.

2.2.3 Extinction test of CPP and locomotor activity

On Day 13, rats were randomly divided into two groups with a similar average of time spent in the cocaine-paired chamber to receive either AMP/SUL and saline or saline alone, in the chamber previously paired with cocaine (Extinction phase). Extinction was executed over four cycles (eight consecutive days) in a similar way as it was conducted in the conditioning phase. The extinction phase was conducted to alleviate cocaine-seeking behavior observed during the post conditioning test, which may mimic the abstinent phase in addicts. Rats received either AMP/SUL or saline on Days 13, 15, 17 and 19 and saline i.p. injections on Days 14, 16, 18 and 20. Injections were also counter-balanced in the same way as it was performed in the conditioning phase. Two i.p. injections were given in the morning, while the following two days, the i.p. injections were administered in the afternoon. On Day 21, rats did not receive any injection, and preference and locomotor tests were performed as described above. In order to consider the rats extinguished, the time spent in the cocaine-paired chamber should be reduced by 25% or more compared to postconditioning test, as described in previous studies (46, 62, 64).

2.2.4 Reinstatement test of CPP and locomotor activity

The day following the extinction test, rats were given a single dose of cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline and confined in the assigned chamber that was given during the conditioning phase for 30 minutes. On the following day, saline i.p. injection was administered similarly. Both injections were given in the morning (reinstatement phase). Reinstatement was performed to mimic relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. On the last day of the experiment, rats did not receive any injections and were tested for reinstatement and locomotor activity as described above (See Fig. 1).

2.3 Brain tissue harvesting

After reinstatement test, rats were rapidly euthanized using CO2 inhalation and promptly decapitated using guillotine. Brains were then placed on dry ice and stored at −80°C. The NAc core and NAc shell as well as the dmPFC were extracted using micro-punch procedure with a cryostat apparatus kept at −20°C to keep the tissue frozen, as described previously (65). Rat Brain Stereotaxic Atlas was used to detect and dissect these brain regions (66). These brain regions were identified through visualized landmarks, such as the appearance of anterior commissure (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Micro-punch sub-regions of the brain targets such as the (A) dmPFC (B) NAc core (closed triangles) and NAc shell (open circles). Images correspond to selected levels (3.7–1.2 mm from bregma) from the atlas of Paxinos & Watson (2007).

2.4 Western blot protocol for detection of GLT-1, xCT, GLAST and mGluR1

Brain samples were lysed using regular lysis buffer as described in previous studies (19–21, 48). Equal amounts of extracted proteins were mixed with 5X laemmli loading dye and then separated in 10% polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were then transferred on a PVDF membrane using transfer apparatus system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were then blocked with 3% milk in TBST (50 mM Tris HCl; 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4; 0.1% Tween 20) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with one of the following primary antibodies: rabbit mGluR1 (1: 3,000; Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents), guinea pig anti-GLT-1 (1:5000, Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents), rabbit anti-xCT antibody (1: 1,000; Abcam), and rabbit anti-EAAT1 (GLAST) antibody (1: 5,000; Abcam). Mouse anti β-tubulin was used as loading control (1:5,000; Cell signaling technology). On the next day, membranes were washed with TBST for five times and then blocked with 3% milk in TBST for 30 minutes. Membranes were further incubated with secondary antibody for 90 minutes at room temperature. Secondary antibodies used in this study are: anti-mouse (1:5,000; Cell signaling technology), anti-rabbit (1:5000; Thermo scientific) and anti-guinea pig (1:5,000; Cell signaling technology). Membranes were then incubated with the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate to detect protein blots and further exposed to Kodak BioMax MR Film (Fisher Inc.); and films were developed on SRX-101A machine. MCID system was used to quantify the detected bands, and the results were presented as a percentage of the ratio of tested protein/β-tubulin, relative to control groups (100% control-value). In each gel run, the water control group was set as 100% and the expression of the protein for each drug treatment group was calculated relative to the water control group. This method has been used in previous studies (67–74).

3. Statistical analysis

Time spent in conditioning chambers as well as the distance traveled were analyzed using two-way repeated measure ANOVA. When significant interaction or significant main effect was shown, Newman-Keuls multiple analysis test was used to compare the effects of the row factor (Days). However, Bonferroni multiple analysis was used when comparing the effects of column factor (treatment or chamber). Immunoblot data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Newman-Keuls as a post hoc test. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used to analyze the effects of AMP/SUL on locomotor activity, since the comparison was done between only two groups. All data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism, represented as p<0.05 level of significance.

4. RESULTS

An unbiased design was used for all the experiments since unpaired two-tailed t-test did not show any significance in time spent among the two chambers (n=25) t (48) = 0.8377, (p= 0.4064).

4.1 Effect of AMP/SUL on cocaine-induced reinstatement using CPP paradigm

4.1.1 Cocaine-saline group

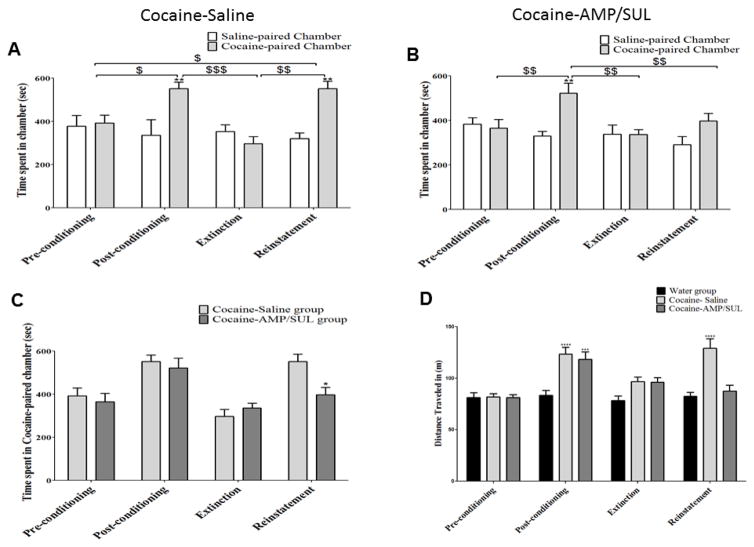

Two-way repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (3, 18) = 6.477, p = 0.0036], a non-significant effect of Chamber [F (1, 6) = 4.157, p = 0.0876], and a significant Day x Chamber interaction [F (3, 18) = 6.558, p = 0.0034] (n=7). Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test showed a significant increase in time spent in the drug-paired chamber at post conditioning test as compared to the pre-conditioning test (p < 0.05, Fig. 2A). A significant decrease in time spent in the drug-paired chamber was found at the extinction test as compared to post-conditioning (p < 0.001; Fig. 2A). Cocaine i.p. injected at the reinstatement phase significantly increased time spent in the drug-paired chamber as compared to extinction (p < 0.01; Fig. 3A) and pre-conditioning (p < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Bonferroni multiple analysis showed an increase in times spent in the cocaine-paired chamber compared to the saline-paired chamber during post-conditioning and reinstatement (p < 0.01; Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Time spent in each conditioning chamber during different CPP phases. A) Two-way repeated measure ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-tests revealed a significant increase in time spent in the cocaine-paired chamber in post conditioning and reinstatement compared to the saline-paired chamber with the cocaine-saline group. B) Two-way repeated measure ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-tests revealed a significant increase in time spent in the cocaine-paired chamber compared to the saline-paired chamber in post conditioning with the cocaine-AMP/SUL group. C) Two-way mixed model ANOVA with repeated measure at each time point, followed by Bonferroni post-tests revealed a significant increase in time spent in the cocaine-paired chamber with the cocaine-saline group compared to the cocaine-AMP/SUL group. D) Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-tests revealed a significant increase in distance in post conditioning and reinstatement with the cocaine-saline group compared to the control group and an increase in distance traveled in post conditioning only with the cocaine-AMP/SUL group compared to the control group. (Values shown as means ± S.E.M. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001 [($ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01 and $$$ p < 0. 001) within cocaine-paired chamber] (n = 6–7 for each group).

4.1.2 Cocaine-AMP/SUL group

Two-way repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (3, 18) = 10.38, p =0.0003], a non-significant effect of Chamber [F (1, 6) = 1.765, p = 0.2323], and a significant Day x Chamber interaction [F (3, 18) = 5. 247, p = 0.0089] (n=7). Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test revealed a significant increase in time spent following conditioning training in drug-paired chamber as compared to pre-conditioning (p < 0.01, Fig. 3B). A significant decrease in time spent in the drug-paired chamber was revealed following extinction training as compared to both post-conditioning (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3B) and reinstatement (p < 0.01; Fig. 3B). Bonferroni multiple analysis showed an increase in time spent in the cocaine-paired chamber compared to the saline-paired chamber during post-conditioning (p < 0.01; Fig. 2B).

4.1.3 Effect of AMP/SUL on time spent in cocaine-paired chamber

Two-way mixed model ANOVA with repeated measure at each time point revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (3, 36) = 30.95, p <0.0001], a non-significant effect of Treatment [F (1, 12) = 1.228, p = 0.2895], and a significant Day x Chamber interaction [F (3, 36) = 5.288, p = 0.004] (n=7). Bonferroni multiple comparisons test revealed a significant decrease in time spent in the cocaine-paired chamber in the cocaine-AMP/SUL group during the reinstatement test, compared to the cocaine-saline group (p < 0.05; Fig. 3C).

4.1.4 Effect of AMP/SUL on CPP behavior and locomotor activity

Two-way repeated measure did not show any significance of the effect of Day on CPP behavior associated with AMP/SUL treatment between the pre-conditioning and post conditioning tests (n=5) [F (1, 4) =1.764, p=0.2548], nor any Chamber effect (saline paired versus AMP/SUL paired chambers) [F (1, 4) =0.3461, p=0.5879] or Day x Chamber interaction [F (1, 4) =1.345, p=0.3107]. AMP/SUL did affect the locomotor activity assessed as distance-traveled of the rats compared to water group using unpaired two-tailed t-test t (9)=0.2470, (p=0.8104) (n=5).

4.1.5 Effect of AMP/SUL on cocaine-induced locomotor activity using CPP apparatus

Two-way repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Day [F (3, 51) = 12.09, p < 0.0001], a significant effect of treatment [F (2, 17) = 30.09, p < 0.0001], and a significant interaction between Days x Treatment [F (6, 51) = 5.363, p = 0.0002]. Bonferroni multiple analysis showed a significant increase in locomotor activity, measured as distance traveled after conditioning training and reinstatement, was revealed with the cocaine-saline group as compared to the water group (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3D). A significant increase in locomotor activity, measured as distance traveled after conditioning training, was also revealed with the cocaine-AMP/SUL group as compared to the water group (p < 0.001; Fig. 3D) (n=6–7).

4.2 Effects of cocaine and AMP/SUL treatment following reinstatement on GLT-1, xCT, GLAST and mGluR1 expression in the NAc core, NAc shell and dmPFC

4.2.1 GLT-1 expression

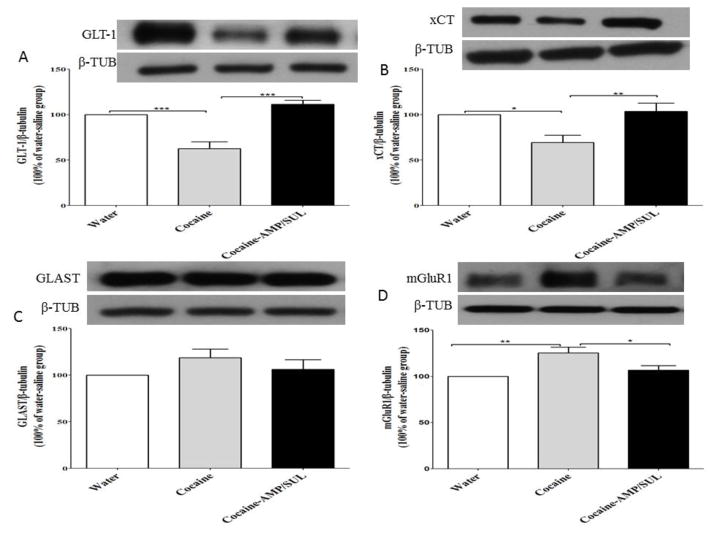

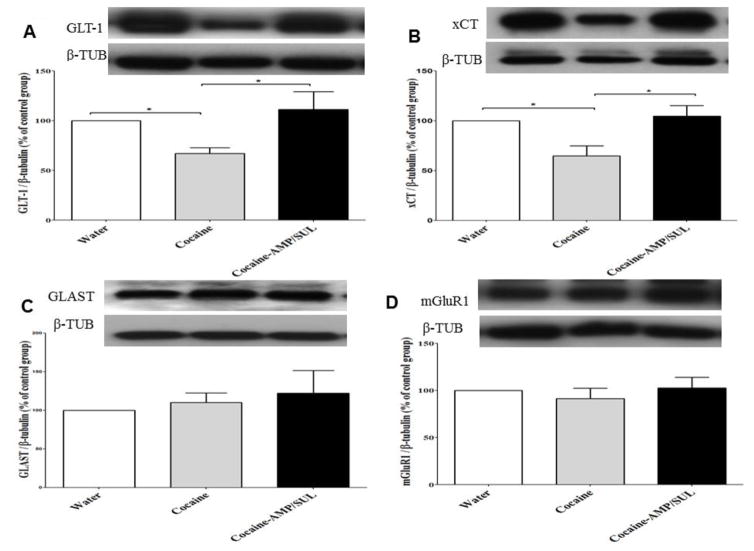

One-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant main effect among the water, cocaine, and cocaine-AMP/SUL groups in the NAc core [F (2, 15) = 24.93, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4A], the NAc shell [F (2, 15) = 4.507, p = 0.0293; Fig. 5A] and the dmPFC [F (2, 15) = 4.116, p = 0.0376; Fig. 6A]. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test showed a significant decrease in the expression of GLT-1 in cocaine-treated rats, as compared to the water rats (p < 0.001; Fig. 4A) and cocaine-AMP/SUL-treated rats (p < 0.001; Fig. 4A), in the NAc core. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test showed a significant decrease in the expression of GLT-1 in the cocaine–treated group, compared to the water group (p < 0.05; Fig. 5A) and cocaine-AMP/SUL-treated group (p < 0.05; Fig. 5A), in the NAc shell. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test also showed a significant increase in the expression of GLT-1 in the cocaine-AMP/SUL-treated group compared to the water group (p < 0.05; Fig. 6A) in the dmPFC (n=6).

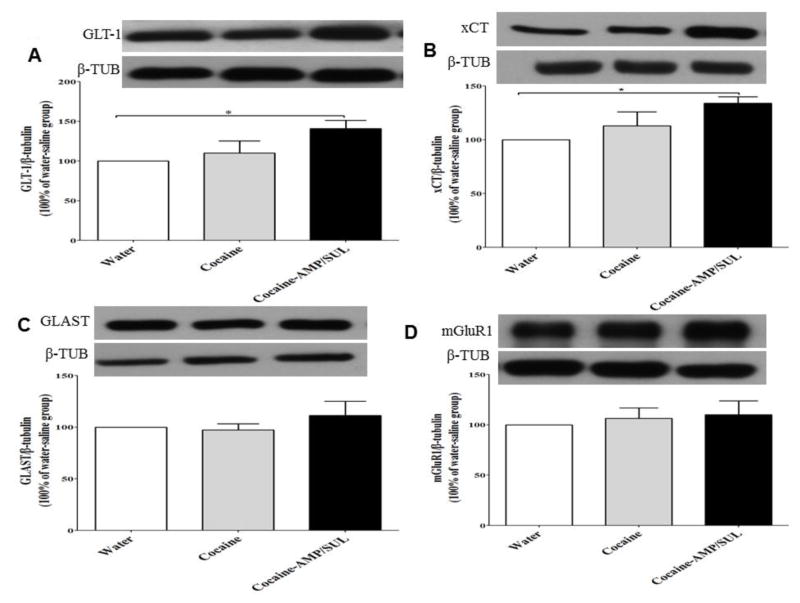

Figure 4.

Effects of cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) and AMP/SUL (200 mg/kg, i.p.) on GLT-1/β-tubulin (A), xCT/β-tubulin (B), GLAST/β-tubulin (C), and mGluR1/β-tubulin in the NAc core. Quantitative analysis revealed a significant decrease in the ratio of GLT-1/β-tubulin and xCT/β-tubulin in the cocaine group compared to the control (water) and cocaine-AMP/SUL groups. No significant difference in the ratio of GLAST/β-tubulin in the NAc core was revealed among all tested groups. There was a significant increase in the ratio of mGluR1/β-tubulin in the cocaine-exposed group as compared to the control (water) and cocaine-AMP/SUL groups. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.05. Values shown as means ± S.E.M. (n = 6 for each group).

Figure 5.

Effects of cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) and AMP/SUL (200 mg/kg, i.p.) on GLT-1/β-tubulin (A), xCT/β-tubulin (B), GLAST/β-tubulin (C), and mGluR1/β-tubulin (D) in the NAc shell. Quantitative analysis revealed a significant decrease in the ratio of GLT-1/β-tubulin and xCT/β-tubulin in the cocaine-exposed group as compared to the control (water) and cocaineMP/SUL groups. No significant difference in the ratio of GLAST/β-tubulin or mGluR1/β-tubulin in the NAc shell was revealed among all tested groups. (* p < 0.05). (Values shown as means ± S.E.M). (n = 6 for each group).

Figure 6.

Effects of cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) and AMP/SUL (200 mg/kg, i.p.) on GLT-1/β-tubulin (A), xCT/β-tubulin (B), GLAST/β-tubulin (C), and mGluR1/β-tubulin (D) in the dmPFC. Quantitative analysis revealed a significant increase in the ratio of GLT-1/β-tubulin and xCT/β-tubulin in the cocaine-exposed group compared to the control group. No significant difference in the ratio of GLAST/β-tubulin or mGluR1/β-tubulin in the dmPFC was revealed among all tested groups. (* p<0.05, Values shown as means ± S.E.M). (n = 6 for each group)

4.2.2 xCT expression

One-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant main effect among the water, cocaine, and cocaine-AMP/SUL groups in the NAc core [F (2, 15) = 7.333, p = 0.006; Fig. 4B], NAc shell [F (2, 15) = 6.585, p = 0.0089; Fig. 5B] and dmPFC [F (2, 15) = 4.361, p = 0.0321; Fig. 6B]. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test showed a significant decrease in the expression of xCT in the cocaine-treated group compared to the water group (p < 0.05; Fig. 3B) and cocaine-AMP/SUL-treated group (p < 0.01; Fig. 4B) in the NAc core. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test showed a significant decrease in the expression of xCT in the cocaine-treated group compared to the water group (p < 0.05; Fig. 6B) and cocaine-AMP/SUL treated group (p < 0.05; Fig. 5B) in the NAc shell. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test showed also a significant increase in the expression of xCT in the cocaine-AMP/SUL-treated group compared to the water group (p < 0.05; Fig. 6B) in the dmPFC (n=6).

4.2.3 GLAST expression

One-way ANOVA analysis revealed a non-significant main effect among the water, cocaine, and cocaine-AMP/SUL groups in the NAc core [F (2, 15) = 1.408, p = 0.2753; Fig. 4C], NAc shell [F (2, 15) = 0.3667, p = 0.6990; Fig. 5C] and dmPFC [F (2, 15) = 0.7257, p = 0.5002; Fig. 6C] (n=6).

4.2.4 mGluR1 expression

One-way ANOVA analysis revealed a non-significant main effect among the water, cocaine, and cocaine-AMP/SUL groups in the NAc shell [F (2, 15) = 0.4106, p = 0.6705; Fig. 5D], and dmPFC [F (2, 15) = 0.2563, p = 0.7772; Fig. 6D]. However, one-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant main effect among the water, cocaine, and cocaine-AMP/SUL groups in the NAc core [F (2, 15) = 7.940, p = 0.0044; Fig. 4D]. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test showed a significant increase in the expression of mGluR1 in the cocaine-treated group compared to the water group (p < 0.01; Fig. 4D) and cocaine-AMP/SUL-treated group (p < 0.05; Fig. 3D) in the NAc core (n=6).

5. DISCUSSION

In this study, we determined the effect of AMP/SUL on cocaine-induced reinstatement using a CPP paradigm. We found that cocaine, given intermittently through i.p. injections for eight days, (4 cycles) induced a place preference in which rats spent significantly more time in the cocaine-paired chamber. In addition, we reported a significant increase in locomotor activity, assessed by measuring distance traveled following exposure to cocaine. Repeated daily saline i.p. injections for eight days effectively extinguished the cocaine-induced place preference and decreased locomotor activity. However, a single non-contingent cocaine i.p. injection induced reinstatement to cocaine-seeking behavior and increased locomotor activity. Our findings are in agreement with previous studies, which showed that four intermittent i.p. injections of cocaine induced place preference and increased locomotor activity as well as that cocaine CPP was extinguished after eight saline i.p. injection (24, 61, 75–79). The acute locomotor responses to drugs of abuse, including cocaine, are mainly dependent on the mesolimbic and nigrostriatal dopaminergic systems, which are known to be regulated by the glutamatergic system (80). Previous findings have reported that acute locomotor responses to various drugs of abuse, including cocaine, were attenuated by several glutamate receptor antagonists, following either systemic delivery at high doses or local delivery into the NAc or striatum (81–83). Importantly, a previous study found that ceftriaxone attenuated locomotor activity, which was induced by acute and repeated cocaine exposure (84). We found here that AMP/SUL treatment reduced both reinstatement to cocaine-seeking behavior and locomotor activity. Our findings indicate that glial glutamate transporters might be involved in cocaine-increased locomotion activity. However, future studies are warranted to determine the specific effects of β-lactam antibiotics on cocaine-increased locomotion activity. Similarly, AMP/SUL did not facilitate extinction; since there was no significant difference in extinction between the AMP/SUL- and saline-treated groups in cocaine –paired chamber. In addition, we found that rats treated with AMP/SUL alone did not affect CPP behavior or have any non-specific effect on locomotor activity compared to saline-treated rats. These results are in agreement with previous studies, which demonstrated that ceftriaxone alone had no effect on CPP behavior when used to attenuate methamphetamine (62) or morphine reinstatement (85). In addition, ceftriaxone treatment had no effect on locomotor activity compared to the saline-treated group (13, 62, 69).

We also investigated the effect of non-contingent cocaine i.p. injection and the modulatory effects of AMP/SUL treatment on GLT-1, xCT and GLAST expression in the NAc core, NAc shell and dmPFC in P rats. GLT-1 and xCT are mostly expressed on astrocytes and represent potential therapeutic target strategies for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases [For review see (11)]. Cocaine decreased GLT-1 and xCT expression in the NAc core and shell, but not in the dmPFC. Importantly, AMP/SUL treatment upregulated GLT-1 and xCT expression in the NAc core, NAc shell and dmPFC. These results are in agreement with previous results from our lab showing that different β-lactam antibiotics upregulated GLT-1 and xCT in the NAc and PFC and consequently attenuated alcohol drinking (18, 21, 74). Moreover, previous studies from our lab reported that β-lactam antibiotics increased GLT-1 and xCT, in part by increasing the expression of nuclear factor kappa-B and phospho-AKT in the NAc (20, 86, 87). This suggests that these signaling pathways could be a possible mechanism for β-lactam antibiotic to upregulate these glial glutamate transporters. However, future studies are needed in the near future to determine whether these pathways are specific for the effects of β-lactam antibiotics on glial glutamate transporters. Evidence suggests the important role of the glutamatergic projections from the PFC to the NAc in cocaine relapse behavior. Findings suggested that chronic exposure to cocaine induces neuroadaptations, including the activation of glutamatergic release within the mesocorticolimbic brain regions. These result in an increase in extracellular glutamate concentration in this circuit, accompanied by an induction and expression of behavioral sensitization (80), and a decrease in basal extracellular glutamate concentrations (88, 89). In addition, exposure to cocaine-paired cues caused an increase in the extracellular glutamate concentration in the NAc, accompanied by an increase in the expression of conditioned locomotion due to significantly lower basal glutamate concentrations (89). It is important to note that chronic exposure to drugs of abuse, including cocaine, have been shown to be involved in the limbic circuit in the NAc shell as well as the motor circuit in the NAc core within the mesocorticolimbic pathways (52, 53, 56, 57). Additionally, ample evidence showed that both circuits are important for mediation of the changes in behavior associated with chronic exposure to drugs of abuse, such as acquisition and craving of cocaine (42, 56).

Chronic exposure to drugs of abuse was accompanied by a reduction in GLT-1 (14, 90, 91), which led to an increase in extracellular glutamate concentration, due in part to a reduction in glutamate clearance in the NAc (6, 13, 46–48, 65, 92, 93). In addition, several studies revealed that GLT-1 was downregulated in the NAc core and NAc shell tissue, but not in the dmPFC, following cocaine self-administration (94, 95) (96). It is noteworthy that the decrease in GLT-1 expression might be strongly associated with length of access and length of withdrawal (92); this decrease was greater in the NAc core than in the NAc shell in long-access animals (97). In agreement with the previous findings, this study showed that cocaine downregulated GLT-1 in the NAc core and NAc shell. Additionally, the basal extracellular glutamate concentration was decreased in the NAc after withdrawal from repeated cocaine exposure (14). Blocking xCT was shown to significantly reduce the basal extracellular glutamate concentration by almost 60%, indicating the key role of xCT in regulating glutamate homeostasis (98). Basal glutamate concentration was regulated through the activation of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors, which, in part, inhibit glutamate release from presynaptic neurons and decrease extracellular glutamate concentrations. Findings have shown that chronic exposure to cocaine reduced xCT activity in the NAc core (99) and xCT expression in the NAc (13). In agreement with the previous findings, we found in this study that cocaine downregulated xCT in the NAc core, and for the first time, we showed that this decrease is not limited to the core but it was also shown in the NAc shell.

Previous studies have found that treating animals with atypical xanthine derivatives, or ceftriaxone, GLT-1 and xCT upregulators, attenuated cue or context-induced cocaine reinstatement (19, 96). Importantly, repeated exposure to N-acetyl cysteine, another GLT-1, and xCT, an up-regulator, attenuated cocaine-seeking behavior in rodents and reduced cravings in cocaine-dependent humans (100). These compounds were found to restore GLT-1 expression in the NAc in cocaine-exposed animals. Similarly, ceftriaxone was shown to upregulate GLT-1 expression in the PFC and to attenuate reinstatement to methamphetamine in a CPP paradigm (62). AMP treatment showed the ability to upregulate GLT-1 (20) and xCT expression in the NAc and the PFC as well as to decrease daily ethanol intake in male P rats (21). In this study, we showed for the first time that AMP/SUL treatment attenuated reinstatement to cocaine and reduced locomotor activity, in part through upregulation of GLT-1 and xCT in the NAc core, NAc shell and dmPFC.

Several studies have reported that mGluRs such as mGluR1 and mGluR5 play a crucial role in cocaine-seeking behavior (30, 101, 102). Indeed, these studies showed that mGluR5 antagonists blocked cocaine CPP, reduced ongoing self-administration cocaine, and attenuated reinstatement to cocaine-seeking behavior in models of relapse. Additionally, previous studies have shown that mGluR5 antagonists reduced cocaine-seeking behavior (103). However, mGluR1 antagonists were found to prevent the context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior when these compounds were infused into the NAc core (104) or dorsal hippocampus (30). Moreover, systemic administration of mGluR1 antagonist attenuated cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization (29). Attenuation of behavioral effects of cocaine and methamphetamine in squirrel monkeys has been observed following exposure to mGluR1 antagonism (28). This indicates that mGluR1 plays a key role in cocaine-seeking behavior. However, there is little known about the effects of cocaine exposure on mGluR1 expression in several central reward brain regions. In this study, cocaine exposure upregulated mGluR1 in the NAc core but not the NAc shell or dmPFC, and these effects were reduced by AMP/SUL treatment. This suggests that β-lactam antibiotics modulate the effects of cocaine exposure on mGluR1 expression and consequently reduce reinstatement to cocaine-seeking behavior.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that a decrease in GLT-1 and xCT expression in the NAc core might lead to an increase in extracellular glutamate concentrations. We suggest that this effect may lead to increase in the firing of medium spiny neurons, which may elevate the expression of postsynaptic glutamate receptors, including mGluR1. AMP/SUL treatment reduced reinstatement to cocaine-seeking behavior and attenuated the cocaine-induced increase in locomotor activity, in part through upregulation of GLT-1 and xCT expression in the NAc core, NAc shell and dmPFC. In addition, AMP/SUL was found here to normalize mGluR1 expression in the NAc core. Our data suggest that the development of reinstatement to cocaine is mediated at least in part by alterations in glial glutamate transporter/receptor expression in central reward brain areas, and β-lactam antibiotics may normalize these effects. However, future studies are warranted to investigate the specific effects of glial glutamate transporters on the reinstatement to cocaine-seeking behavior. Thus, glial glutamate transporter blockers or vivo-morpholino methods could be utilized to correlate the specific relationship between these transporters and cocaine-seeking behavior.

Highlight.

Cocaine downregulated GLT-1 and xCT in the NAc core and shell but not dmPFC.

Cocaine upregulated mGluR1 in the NAc core but not shell or dmPFC

AMP/SUL attenuated reinstatement to cocaine seeking behavior.

AMP/SUL normalized GLT-1, xCT and mGluR 1 in the mesocorticolimbic regions.

AMP/SUL attenuated cocaine-increased locomotion activity.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by Award Number R01AA019458 (YS) from the National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and fund provided by The University of Toledo. Alaa M. Hammad was supported by a scholarship from Al-Zaytoonah University, College of Pharmacy, Amman, Jordan.

The authors would like to thank Dr. F. Scott Hall for allowing us to use the ANY-maze tracking system for the locomotor activity data. The authors would like to thank Mrs. Charisse Montgomery for editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McLaughlin J, See RE. Selective inactivation of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and the basolateral amygdala attenuates conditioned-cued reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168(1–2):57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McFarland K, Lapish CC, Kalivas PW. Prefrontal glutamate release into the core of the nucleus accumbens mediates cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23(8):3531–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03531.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reid MS, Berger SP. Evidence for sensitization of cocaine-induced nucleus accumbens glutamate release. Neuroreport. 1996;7(7):1325–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199605170-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Self DW, Choi KH, Simmons D, Walker JR, Smagula CS. Extinction training regulates neuroadaptive responses to withdrawal from chronic cocaine self-administration. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY) 2004;11(5):648–57. doi: 10.1101/lm.81404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutton MA, Schmidt EF, Choi KH, Schad CA, Whisler K, Simmons D, et al. Extinction-induced upregulation in AMPA receptors reduces cocaine-seeking behaviour. Nature. 2003;421(6918):70–5. doi: 10.1038/nature01249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knackstedt LA, Kalivas PW. Glutamate and reinstatement. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2009;9(1):59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornish JL, Kalivas PW. Glutamate transmission in the nucleus accumbens mediates relapse in cocaine addiction. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2000;20(15):Rc89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-j0006.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. Dissociable effects of antagonism of NMDA and AMPA/KA receptors in the nucleus accumbens core and shell on cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(3):341–60. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McFarland K, Davidge SB, Lapish CC, Kalivas PW. Limbic and motor circuitry underlying footshock-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24(7):1551–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4177-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee A, Pow DV. Astrocytes: Glutamate transport and alternate splicing of transporters. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2010;42(12):1901–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy-Royal C, Dupuis J, Groc L, Oliet SH. Astroglial glutamate transporters in the brain: Regulating neurotransmitter homeostasis and synaptic transmission. 2017 doi: 10.1002/jnr.24029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Progress in neurobiology. 2001;65(1):1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knackstedt LA, Melendez RI, Kalivas PW. Ceftriaxone restores glutamate homeostasis and prevents relapse to cocaine seeking. Biological psychiatry. 2010;67(1):81–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker DA, McFarland K, Lake RW, Shen H, Tang XC, Toda S, et al. Neuroadaptations in cystine-glutamate exchange underlie cocaine relapse. Nature neuroscience. 2003;6(7):743–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madayag A, Lobner D, Kau KS, Mantsch JR, Abdulhameed O, Hearing M, et al. Repeated N-acetylcysteine administration alters plasticity-dependent effects of cocaine. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27(51):13968–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2808-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams SM, Sullivan RK, Scott HL, Finkelstein DI, Colditz PB, Lingwood BE, et al. Glial glutamate transporter expression patterns in brains from multiple mammalian species. Glia. 2005;49(4):520–41. doi: 10.1002/glia.20139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, Haenggeli C, Huang YH, Bergles DE, et al. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature. 2005;433(7021):73–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alasmari F, Rao PS, Sari Y. Effects of cefazolin and cefoperazone on glutamate transporter 1 isoforms and cystine/glutamate exchanger as well as alcohol drinking behavior in male alcohol-preferring rats. Brain research. 2016;1634:150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sari Y, Smith KD, Ali PK, Rebec GV. Upregulation of GLT1 attenuates cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29(29):9239–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1746-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao PS, Goodwani S, Bell RL, Wei Y, Boddu SH, Sari Y. Effects of ampicillin, cefazolin and cefoperazone treatments on GLT-1 expressions in the mesocorticolimbic system and ethanol intake in alcohol-preferring rats. Neuroscience. 2015;295:164–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alasmari F, Abuhamdah S, Sari Y. Effects of ampicillin on cystine/glutamate antiporter and glutamate transporter 1 isoforms as well as ethanol drinking in male P rats. Neuroscience letters. 2015;600:148–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bardo MT, Rowlett JK, Harris MJ. Conditioned place preference using opiate and stimulant drugs: a meta-analysis. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 1995;19(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00021-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreibich AS, Blendy JA. cAMP response element-binding protein is required for stress but not cocaine-induced reinstatement. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24(30):6686–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller D, Stewart J. Cocaine-induced conditioned place preference: reinstatement by priming injections of cocaine after extinction. Behavioural brain research. 2000;115(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hubert GW, Paquet M, Smith Y. Differential subcellular localization of mGluR1a and mGluR5 in the rat and monkey Substantia nigra. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21(6):1838–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01838.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Distribution of the mRNA for a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1) in the central nervous system: an in situ hybridization study in adult and developing rat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1992;322(1):121–35. doi: 10.1002/cne.903220110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shigemoto R, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Sugihara H, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Immunohistochemical localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR5, in the rat brain. Neuroscience letters. 1993;163(1):53–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90227-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Achat-Mendes C, Platt DM, Spealman RD. Antagonism of metabotropic glutamate 1 receptors attenuates behavioral effects of cocaine and methamphetamine in squirrel monkeys. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2012;343(1):214–24. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.196295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dravolina OA, Danysz W, Bespalov AY. Effects of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists on the behavioral sensitization to motor effects of cocaine in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187(4):397–404. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie X, Ramirez DR, Lasseter HC, Fuchs RA. Effects of mGluR1 antagonism in the dorsal hippocampus on drug context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1700-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu F, Zhong P, Liu X, Sun D, Gao HQ, Liu QS. Metabotropic glutamate receptor I (mGluR1) antagonism impairs cocaine-induced conditioned place preference via inhibition of protein synthesis. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(7):1308–21. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(8):1403–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ito R, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Differential control over cocaine-seeking behavior by nucleus accumbens core and shell. Nature neuroscience. 2004;7(4):389–97. doi: 10.1038/nn1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parkinson JA, Olmstead MC, Burns LH, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Dissociation in effects of lesions of the nucleus accumbens core and shell on appetitive pavlovian approach behavior and the potentiation of conditioned reinforcement and locomotor activity by D-amphetamine. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19(6):2401–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02401.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lecca D, Piras G, Driscoll P, Giorgi O, Corda MG. A differential activation of dopamine output in the shell and core of the nucleus accumbens is associated with the motor responses to addictive drugs: a brain dialysis study in Roman high- and low-avoidance rats. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46(5):688–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Chiara G. Nucleus accumbens shell and core dopamine: differential role in behavior and addiction. Behavioural brain research. 2002;137(1–2):75–114. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Backstrom P, Hyytia P. Involvement of AMPA/kainate, NMDA, and mGlu5 receptors in the nucleus accumbens core in cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192(4):571–80. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0753-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Famous KR, Schmidt HD, Pierce RC. When administered into the nucleus accumbens core or shell, the NMDA receptor antagonist AP-5 reinstates cocaine-seeking behavior in the rat. Neuroscience letters. 2007;420(2):169–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guillem K, Ahmed SH, Peoples LL. Escalation of cocaine intake and incubation of cocaine seeking are correlated with dissociable neuronal processes in different accumbens subregions. Biological psychiatry. 2014;76(1):31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. The American journal of psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1642–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berglind WJ, Whitfield TW, Jr, LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW, McGinty JF. A single intra-PFC infusion of BDNF prevents cocaine-induced alterations in extracellular glutamate within the nucleus accumbens. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29(12):3715–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5457-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McFarland K, Kalivas PW. The circuitry mediating cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21(21):8655–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08655.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalivas PW, McFarland K. Brain circuitry and the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168(1–2):44–56. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rocha A, Kalivas PW. Role of the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens in reinstating methamphetamine seeking. The European journal of neuroscience. 2010;31(5):903–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grimm JW, Shaham Y, Hope BT. Effect of cocaine and sucrose withdrawal period on extinction behavior, cue-induced reinstatement, and protein levels of the dopamine transporter and tyrosine hydroxylase in limbic and cortical areas in rats. Behavioural pharmacology. 2002;13(5–6):379–88. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200209000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujio M, Nakagawa T, Sekiya Y, Ozawa T, Suzuki Y, Minami M, et al. Gene transfer of GLT-1, a glutamate transporter, into the nucleus accumbens shell attenuates methamphetamine- and morphine-induced conditioned place preference in rats. The European journal of neuroscience. 2005;22(11):2744–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melendez RI, Hicks MP, Cagle SS, Kalivas PW. Ethanol exposure decreases glutamate uptake in the nucleus accumbens. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(3):326–33. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156086.65665.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Das SC, Yamamoto BK, Hristov AM, Sari Y. Ceftriaxone attenuates ethanol drinking and restores extracellular glutamate concentration through normalization of GLT-1 in nucleus accumbens of male alcohol-preferring rats. Neuropharmacology. 2015;97:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gass JT, Olive MF. Glutamatergic substrates of drug addiction and alcoholism. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(1):218–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zahm DS, Brog JS. On the significance of subterritories in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum. Neuroscience. 1992;50(4):751–67. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90202-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Groenewegen HJ, Wright CI, Beijer AV. The nucleus accumbens: gateway for limbic structures to reach the motor system? Progress in brain research. 1996;107:485–511. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61883-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grimm JW, See RE. Dissociation of primary and secondary reward-relevant limbic nuclei in an animal model of relapse. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22(5):473–9. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meil WM, See RE. Lesions of the basolateral amygdala abolish the ability of drug associated cues to reinstate responding during withdrawal from self-administered cocaine. Behavioural brain research. 1997;87(2):139–48. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weissenborn R, Whitelaw R, Robbins T, Everitt B. Excitotoxic lesions of the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus attenuate intravenous cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology. 1998;140(2):225–32. doi: 10.1007/s002130050761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nestler EJ, Aghajanian GK. Molecular and cellular basis of addiction. Science. 1997;278(5335):58–63. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, Fitzgerald J, Reivich M, O’brien CP. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(1):11–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grant S, London ED, Newlin DB, Villemagne VL, Liu X, Contoreggi C, et al. Activation of memory circuits during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1996;93(21):12040–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katner SN, Oster SM, Ding ZM, Deehan GA, Jr, Toalston JE, Hauser SR, et al. Alcohol-preferring (P) rats are more sensitive than Wistar rats to the reinforcing effects of cocaine self-administered directly into the nucleus accumbens shell. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2011;99(4):688–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hammad AM, Althobaiti YS, Das SC, Sari Y. Effects of repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal on voluntary ethanol drinking, and the expression of glial glutamate transporters in mesocorticolimbic system of P rats. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin JL, Itzhak Y. 7-Nitroindazole blocks nicotine-induced conditioned place preference but not LiCl-induced conditioned place aversion. Neuroreport. 2000;11(5):947–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200004070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Itzhak Y, Martin JL. Cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in mice: induction, extinction and reinstatement by related psychostimulants. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26(1):130–4. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abulseoud OA, Miller JD, Wu J, Choi DS, Holschneider DP. Ceftriaxone upregulates the glutamate transporter in medial prefrontal cortex and blocks reinstatement of methamphetamine seeking in a condition place preference paradigm. Brain research. 2012;1456:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nature protocols. 2006;1(4):1662–70. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hiroi N, White NM. The amphetamine conditioned place preference: differential involvement of dopamine receptor subtypes and two dopaminergic terminal areas. Brain research. 1991;552(1):141–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90672-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sari Y, Sreemantula SN. Neuroimmunophilin GPI-1046 reduces ethanol consumption in part through activation of GLT1 in alcohol-preferring rats. Neuroscience. 2012;227:327–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 6. Amsterdam; Boston: Academic Press/Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li J, Olinger AB, Dassow MS, Abel MS. Up-regulation of GABA(B) receptor mRNA and protein in the hippocampus of cocaine- and lidocaine-kindled rats. Neuroscience. 2003;118(2):451–62. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Raval AP, Dave KR, Mochly-Rosen D, Sick TJ, Perez-Pinzon MA. Epsilon PKC is required for the induction of tolerance by ischemic and NMDA-mediated preconditioning in the organotypic hippocampal slice. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23(2):384–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00384.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller BR, Dorner JL, Shou M, Sari Y, Barton SJ, Sengelaub DR, et al. Up-regulation of GLT1 expression increases glutamate uptake and attenuates the Huntington’s disease phenotype in the R6/2 mouse. Neuroscience. 2008;153(1):329–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Q, Tan Y. Nerve growth factor augments neuronal responsiveness to noradrenaline in cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons of rats. Neuroscience. 2011;193:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simoes AP, Duarte JA, Agasse F, Canas PM, Tome AR, Agostinho P, et al. Blockade of adenosine A2A receptors prevents interleukin-1beta-induced exacerbation of neuronal toxicity through a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2012;9:204. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pozo Devoto VM, Bogetti ME, Fiszer de Plazas S. Developmental and hypoxia-induced cell death share common ultrastructural and biochemical apoptotic features in the central nervous system. Neuroscience. 2013;252:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Althobaiti YS, Alshehri FS, Almalki AH, Sari Y. Effects of Ceftriaxone on Glial Glutamate Transporters in Wistar Rats Administered Sequential Ethanol and Methamphetamine. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2016;10:427. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hakami AY, Hammad AM, Sari Y. Effects of Amoxicillin and Augmentin on Cystine-Glutamate Exchanger and Glutamate Transporter 1 Isoforms as well as Ethanol Intake in Alcohol-Preferring Rats. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2016;10:171. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zheng D, Cabeza de Vaca S, Jurkowski Z, Carr KD. Nucleus accumbens AMPA receptor involvement in cocaine-conditioned place preference under different dietary conditions in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232(13):2313–22. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3863-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nygard SK, Klambatsen A, Balouch B, Quinones-Jenab V, Jenab S. Region and context-specific intracellular responses associated with cocaine-induced conditioned place preference expression. Neuroscience. 2015;287:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Busse GD, Riley AL. Cocaine, but not alcohol, reinstates cocaine-induced place preferences. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2004;78(4):827–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Busse GD, Riley AL. Modulation of cocaine-induced place preferences by alcohol. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2002;26(7–8):1373–81. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Collins GT, Chen Y, Tschumi C, Rush EL, Mensah A, Koek W, et al. Effects of consuming a diet high in fat and/or sugar on the locomotor effects of acute and repeated cocaine in male and female C57BL/6J mice. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2015;23(4):228–37. doi: 10.1037/pha0000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wolf ME. The role of excitatory amino acids in behavioral sensitization to psychomotor stimulants. Progress in neurobiology. 1998;54(6):679–720. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bedingfield JB, Calder LD, Thai DK, Karler R. The role of the striatum in the mouse in behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 1997;56(2):305–10. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karler R, Calder LD. Excitatory amino acids and the actions of cocaine. Brain research. 1992;582(1):143–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pulvirenti L, Swerdlow NR, Koob GF. Microinjection of a glutamate antagonist into the nucleus accumbens reduces psychostimulant locomotion in rats. Neuroscience letters. 1989;103(2):213–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tallarida CS, Corley G, Kovalevich J, Yen W, Langford D, Rawls SM. Ceftriaxone attenuates locomotor activity induced by acute and repeated cocaine exposure in mice. Neuroscience letters. 2013;556:155–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.09.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fan Y, Niu H, Rizak JD, Li L, Wang G, Xu L, et al. Combined action of MK-801 and ceftriaxone impairs the acquisition and reinstatement of morphine-induced conditioned place preference, and delays morphine extinction in rats. Neuroscience bulletin. 2012;28(5):567–76. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1269-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goodwani S, Rao PS, Bell RL, Sari Y. Amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate reduce ethanol intake and increase GLT-1 expression as well as AKT phosphorylation in mesocorticolimbic regions. Brain research. 2015;1622:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rao PS, Saternos H, Goodwani S, Sari Y. Effects of ceftriaxone on GLT1 isoforms, xCT and associated signaling pathways in P rats exposed to ethanol. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232(13):2333–42. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3868-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pierce RC, Bell K, Duffy P, Kalivas PW. Repeated cocaine augments excitatory amino acid transmission in the nucleus accumbens only in rats having developed behavioral sensitization. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16(4):1550–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01550.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hotsenpiller G, Giorgetti M, Wolf ME. Alterations in behaviour and glutamate transmission following presentation of stimuli previously associated with cocaine exposure. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;14(11):1843–55. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kalivas PW. The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(8):561–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wolf ME, Ferrario CR. AMPA receptor plasticity in the nucleus accumbens after repeated exposure to cocaine. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2010;35(2):185–211. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fischer KD, Houston AC, Rebec GV. Role of the major glutamate transporter GLT1 in nucleus accumbens core versus shell in cue-induced cocaine-seeking behavior. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33(22):9319–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3278-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shen Y, Tian Y, Shi X, Yang J, Ouyang L, Gao J, et al. Exposure to high glutamate concentration activates aerobic glycolysis but inhibits ATP-linked respiration in cultured cortical astrocytes. Cell biochemistry and function. 2014;32(6):530–7. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reissner KJ, Gipson CD, Tran PK, Knackstedt LA, Scofield MD, Kalivas PW. Glutamate transporter GLT-1 mediates N-acetylcysteine inhibition of cocaine reinstatement. Addict Biol. 2015;20(2):316–23. doi: 10.1111/adb.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sondheimer I, Knackstedt LA. Ceftriaxone prevents the induction of cocaine sensitization and produces enduring attenuation of cue- and cocaine-primed reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Behavioural brain research. 2011;225(1):252–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reissner KJ, Brown RM, Spencer S, Tran PK, Thomas CA, Kalivas PW. Chronic administration of the methylxanthine propentofylline impairs reinstatement to cocaine by a GLT-1-dependent mechanism. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(2):499–506. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fischer-Smith KD, Houston AC, Rebec GV. Differential effects of cocaine access and withdrawal on glutamate type 1 transporter expression in rat nucleus accumbens core and shell. Neuroscience. 2012;210:333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Baker DA, Xi ZX, Shen H, Swanson CJ, Kalivas PW. The origin and neuronal function of in vivo nonsynaptic glutamate. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22(20):9134–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-09134.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Trantham-Davidson H, LaLumiere RT, Reissner KJ, Kalivas PW, Knackstedt LA. Ceftriaxone normalizes nucleus accumbens synaptic transmission, glutamate transport, and export following cocaine self-administration and extinction training. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32(36):12406–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1976-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Amen SL, Piacentine LB, Ahmad ME, Li SJ, Mantsch JR, Risinger RC, et al. Repeated N-acetyl cysteine reduces cocaine seeking in rodents and craving in cocaine-dependent humans. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(4):871–8. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chiamulera C, Epping-Jordan MP, Zocchi A, Marcon C, Cottiny C, Tacconi S, et al. Reinforcing and locomotor stimulant effects of cocaine are absent in mGluR5 null mutant mice. Nature neuroscience. 2001;4(9):873–4. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kumaresan V, Yuan M, Yee J, Famous KR, Anderson SM, Schmidt HD, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) antagonists attenuate cocaine priming- and cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Behavioural brain research. 2009;202(2):238–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McGeehan AJ, Olive MF. The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP reduces the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine but not other drugs of abuse. Synapse (New York, NY) 2003;47(3):240–2. doi: 10.1002/syn.10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xie X, Lasseter HC, Ramirez DR, Ponds KL, Wells AM, Fuchs RA. Subregion-specific role of glutamate receptors in the nucleus accumbens on drug context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Addiction biology. 2012;17(2):287–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]