Abstract

A practical method for enantioselective synthesis of fluoroalkyl-substituted Z-homoallylic tertiary alcohols has been developed. Reactions may be performed with ketones containing a polylfluoro-, trifluoro-, difluoro- and monofluoroalkyl group along with an aryl, a heteroaryl, an alkenyl, an alkynyl, or an alkyl substituent. Readily accessible unsaturated organoboron compounds serve as reagents. Transformations were performed with 0.5–2.5 mol % of a boron-based catalyst, generated in situ from a readily accessible valine-derived aminophenol and a Z- or an E-γ-substituted boronic acid pinacol ester. With a Z organoboron reagent, additions to trifluoromethyl and polyfluoroalkyl ketones proceeded in 80–98% yield, 97:3 to >98:2 α:γ selectivity, >95:5 Z:E selectivity and 81:19 to >99:1 enantiomeric ratio. In notable contrast to reactions with unsubstituted allylboronic acid pinacol ester, additions to ketones with a mono- or a difluoromethyl group were highly enantioselective as well. Transformations were similarly efficient, α- and Z-selective when an E-allylboronate compound was used, but enantioselectivities were lower and, in certain cases, the opposite enantiomer was favored (up to 4:96 er). With a racemic allylboronate reagent that contains an allylic stereogenic center, additions were exceptionally α-selective, affording products, expected from γ-addition of a crotylboron compound, in up to 97% yield, 88:12 diastereomeric ratio and 94:6 enantiomeric ratio. Utility is highlighted by gram scale preparation of representative products through transformations that were performed without exclusion of air or moisture, and through applications in stereoselective olefin metathesis where Z-alkene substrates are required. Mechanistic investigations aided by computational (DFT) studies were carried out and offer insight into different selectivity profiles.

TOC Graphic

Introduction

Small organic molecules bearing a fluoroalkyl-substituted carbon stereogenic center are central to development of therapeutics,1 agrochemicals2 and materials.3 Practical, efficient, cost-effective and broadly applicable catalytic methods that generate such entities with high enantioselectivity are much sought after. Although such catalytic processes can deliver valuable and readily modifiable building blocks in high enantiomeric purity, they remain relatively uncommon.4,5,6,7 The limited number of reported studies entail additions of allyl units to a small set of trifluoromethyl ketones, need significant amounts4a–b (at times several equivalents4a) of costly indium salts, can require days to reach completion,4b and selectivities do not exceed 90:10 er (enantiomeric ratio).4c Part of the challenge in developing such transformations is the comparatively small difference in the size of the carbonyl substituents and high electrophilicity causing non-selective background addition. Thus, high enantioselectivity must be attained by incorporation of well-defined electronic factors.

We have demonstrated that valine-derived chiral organoboron catalysts (Scheme 1),8 which probably exist in solution as ammonium salt derivatives, promote the addition of symmetric allyl– and allenyl–B(pin) compounds9 (pin = pinacolato) as well as silyl-protected proparyl–B(pin) reagents to trifluoromethyl ketones efficiently and with high α- and enantioselectivity (up to >98:2 α:γ and 99:1 er; Scheme 1a).10 A collection of experimental and computational data suggests that in the favored mode of addition i (Scheme 1) there is minimization of electron–electron repulsion caused by the non-bonding electrons of the ketone oxygen and the fluorine atoms through electrostatic interaction with the catalyst’s ammonium group. We later showed that with a phosphinoylimine and the more Lewis acidic Zn(OMe)2 (vs NaOt-Bu) reaction of γ-substituted allyl–B(pin) compounds proceed more efficiently and with far higher γ selectivity (Scheme 1b).11 Preferential formation of the γ-addition products likely arises from the ability of the Lewis acidic Zn salt to cause 1,3-boryl shift12 (ii → iii → Z-iv, Scheme 1b) to occur faster than the addition of the initially generated chiral allylboron intermediate to an imine (i.e., in Scheme 1b: ii → α-addition product).

Scheme 1.

Relevant Previous Observations

The above findings point raise a key question: Would the 1,3-borotropic shift afford the γ-addition product (vi via v, Scheme 2) faster, or would the corresponding α-addition product viii (via vii) be generated preferentially in the case of more electrophilic trifluoromethyl ketones? If γ-selective, would the diastereomeric ratio (dr) and er be high? If α-selective, would er be high, would the product contain an E- or a Z-alkene and to what degree would E:Z selectivity be under catalyst control and/or depend on the stereochemistry of the organoboron reagent? Would additions to the less electrophilic difluoro- and monofluoromethyl ketone analogues occur with much lower enantioelectivity, as they did when symmetric allyl–B(pin) compounds were used or will the new method offer broader scope?10

Scheme 2.

Goals of this Study

Here, we describe the results of studies designed to address the above questions. We detail the development of a practical, broadly applicable, highly efficient, α-selective, Z-selective and enantioselective additions to fluoroalkyl ketones. The considerable scope of the catalytic protocol, its utility in chemical synthesis, the role of the stereochemical identity of the organoboron reagent, the origin of high α-, Z- and enantioselectivity as well as the mechanistic basis for the observed trends in reactivity and selectivity are presented below.

Results and Discussion

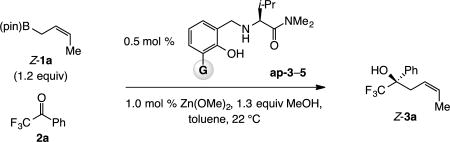

1. Initial evaluation

We first examined the addition of organoboron reagent Z-1a to trifluoroacetophenone 2a (Scheme 3). With ligand ap-1 (ap = aminophenol), reaction was complete in 12 h at 22 °C, affording 3a in 85% yield, >98:2 α:γ ratio, 83:17 Z:E selectivity and 98:2 er. The transformation was much faster at 60 °C (>98% conv, 30 min) and 3a was isolated in 86% yield and 98:2 er, with only slightly lower α:γ selectivity (96:4), but Z selectivity was reduced significantly (79:21 Z:E). The transformation with ap-2 was similarly efficient and selective, which was unexpected since previous studies had indicated transformations with a carboxylic ester (vs dialkyl amide) are less efficient and less enantioselective.8 With sterically more demanding triphenylsilyl-substituted ap-3,6k,10 efficiency (87–88% yield), α selectivity (>98:2) and er (≥98:2) remained high (Scheme 3), along with a boost in reaction rate (45 min) and Z selectivity, regardless of the reaction temperature (≥96:4 vs 74:26–83:17 Z:E with ap-1,2). The importance of this finding regarding utility in synthesis aside, the clear influence of catalyst structure on Z:E selectivity is notable (see below for analysis). When NaOt-Bu was used instead of Zn(OMe)2, there was only 12% conversion after 28 h (22 °C, >98:2 α:γ, 97:3 Z:E, 98:2 er). As discussed previously,11 the positive effect of the Zn(II) salt on efficiency is probably tied to its coordination to the catalyst’s amide carbonyl, its diminished ability to coordinate to the boron center and reduced catalyst activity.

Scheme 3.

Initial Examination of Reactivity and Selectivity

aReactions carried out under N2 atm. Conv and α:γ ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields for purified α-addition products (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). Experiments were run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

With acetophenone (vs the trifluoromethyl variant) and ap-3 the γ-addition product was slightly favored (62% 6, eq 1). This suggests that with a less electrophilic ketone, Lewis acid catalyzed 1,3-borotropic shift becomes more competitive (see ii → Z-iv vs ii → vii, Scheme 2). The near-complete erosion of Z selectivity (60:40 vs 97:3 Z:E; eq 1) indicates that the presence of the trifluoromethyl group is key to the formation of the higher energy alkene isomer. The mechanistic origins of this effect and whether a difluoro- or a monofluoromethyl group would have a similar influence on various selectivity issues remained to be determined.

|

(1) |

2. Scope

2.1. Additions to trifluoromethyl ketones

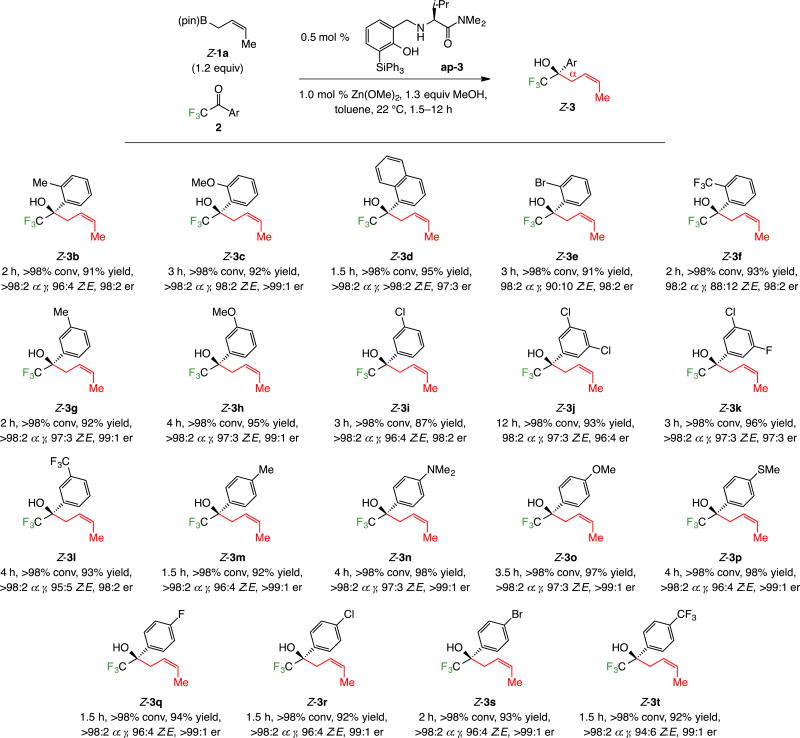

With 0.5 mol % ap-3, 1.0 mol % Zn(OMe)2 and 1.2 equivalents of commercially available Z-1a (used as received), additions to a variety of aryl-substituted trifluoromethyl ketones proceeded to completion at 22 °C in 1.5–12 hours (Scheme 4). Products were isolated in 87–98% yield, ≥98:2 α:γ selectivity, 88:12 to >98:2 Z:E selectivity and 96:4 to >99:1 er. Substrates containing a sterically congested (e.g., 3b, 3d–f, Scheme 4), electron-rich (e.g., 3c, 3h, 3o) or electron-deficient (e.g., 3l, 3f) aryl group were suitable. Dimethylaminophenyl-substituted 3n and methylthiophenyl-substituted 3p were readily generated with exceptional efficiency and selectivity.

Scheme 4.

Reactions with Aryl-Substituted Trifluoromethylketonesa

aReactions carried out under N2 atm. Conv, α:γ and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields for purified α-addition products (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). All experiments run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

Heterocyclic substrates can be converted to the corresponding homoallylic alcohols (Scheme 5). Indole- (7), furyl- (8a–b), thienyl- (9a–b), and pyridyl-substituted (10) homoallylic alcohols were isolated in up to 98% yield, >98% α selectivity, 98% Z selectivity and >99:1 er. The lower er in the reactions with 2-furyl and 2-thienyl ketones compared to their 3-substituted analogues are consistent with formerly disclosed observations regarding allyl–B(pin), and allenyl–B(pin) additions.10 Regarding pyridyl product 10, 2.5 mol % ap-3, 5.0 mol % Zn(OMe)2, 12 hours, and 60 °C were required for >98% conversion; this might be in part because the corresponding hydrate was the starting material. The X-ray structure secured for Z-10 allowed us to establish the absolute stereochemical identity of the major product.13

Scheme 5.

Reactions with Heteroaryl-Substituted Trifluoromethyl Ketonesa

aReactions carried out under N2 atm. Conv, α:γ and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields for purified α-addition products (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). All experiments run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

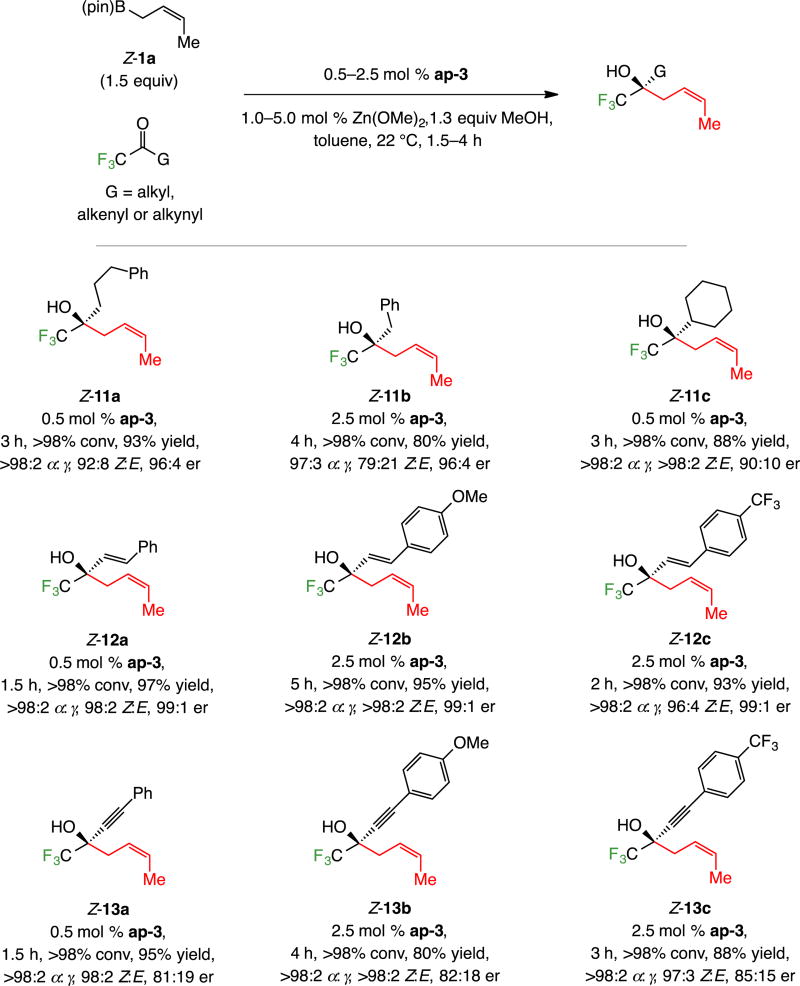

Additions to other alkyl-substituted trifluoromethyl ketones (11a–c, Scheme 6), including cyclohexyl-substituted 11c proceeded to >98% conversion with 0.5 mol % ap-3 (one case at 2.5 mol %) at 22 °C in four hours (Scheme 6). Transformations were efficient (80–97% yield), generating the α-addition products with considerable selectivity (97:3 to >99:1 α:γ). Levels of Z selectivity were surprisingly variable: benzyl-substituted 11b being formed in 79:21 Z:E ratio (vs 92:8 and >98:2 for 11a and 11c, respectively). There was a less dramatic fluctuation in enantioselectivity with cyclohexyl-substituted 11c (90:10 er vs 96:4 for 11a and 11b; see below for mechanistic analysis).

Scheme 6.

Reactions with Alkyl-, Alkenyl- and Alkynyl-Substituted Trifluoromethyl Ketonesa

aReactions carried out under N2 atm. Conv, α:γ and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields for purified α-addition products (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). All experiments run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

Reaction of the α,β-unsaturated trifluoromethyl-substituted ketones afforded dienes 12a–c (Scheme 6) in 93–97% yield, >98:2 α:γ selectivity, ≥98:2 Z:E selectivity and 99:1 er. Reactions affording 1,5-enynes 13a–c were similarly efficient, α-, and Z-selective (Scheme 6), but enantioselectivities were notably lower (81:19–85:15 er; see below for rationale).

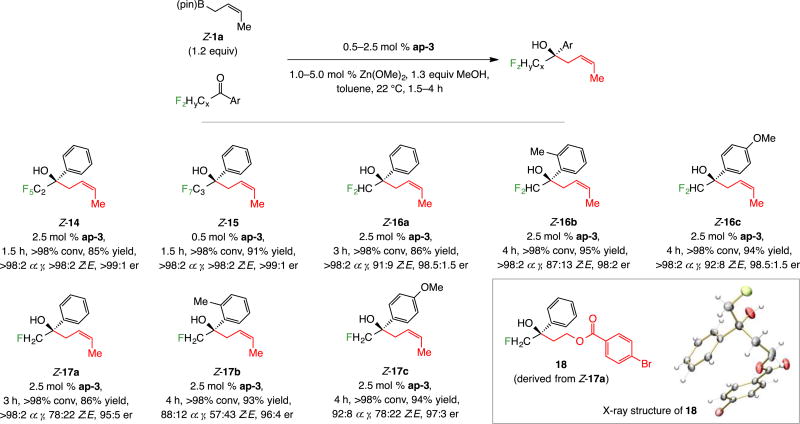

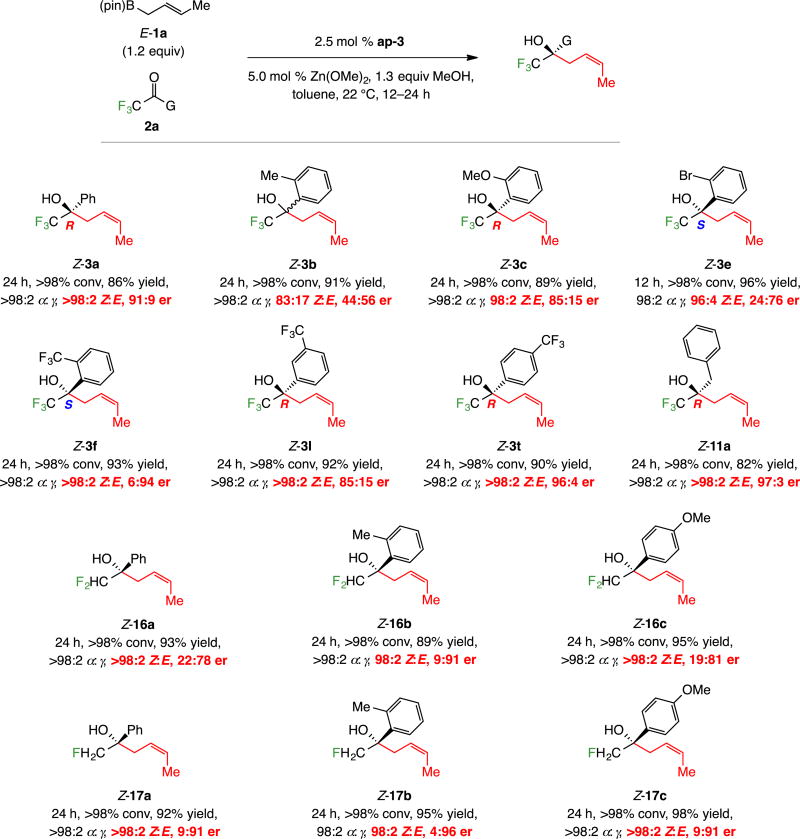

2.2. Additions to polyfluoroalkyl di- and monofluoromethyl ketones

Polyfluorinated products 14 and 15 were generated efficiently and with α selectivity, Z selectivity and er. The highly enantioselective formation of difluoro- and monofluoro-substituted 16a–c and 17a–c, on the other hand, were unexpected (96:4–98.5:1.5 er, Scheme 7); this was because addition of allyl–B(pin) to these same ketones was minimally enantioselective (Scheme 1a).10 The X-ray structure of p-bromobenzoate derivative 18 showed that there was no change in the sense of stereochemical induction (vs the trifluoromethyl analogs). Moreover, these data show that the number of fluorine atoms adjacent to the ketone unit has considerable influence on Z selectivity of the process: Z:E ratio descended in the order of 97:3 (Z-3a, Scheme 3) to 91:9 (Z-16a, Scheme 7) to 78:22 (Z-17a) with three, two and one fluorine atom on the α-alkyl site, respectively. The outcome of the reactions with di- and monofluoromethyl-substituted ketones constitutes one of the more distinct advantages of the present approach to reactions with allyl– B(pin),10 where low er was observed with substrates containing a smaller number of fluorine atoms (see below for additional examples and analysis).

Scheme 7.

Reactions with Other Fluoroalkyl-Substituted Ketonesa

aReactions carried out under N2 atm. Conv, α:γ and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields for purified α-addition products except for 17b–c (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). All experiments run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

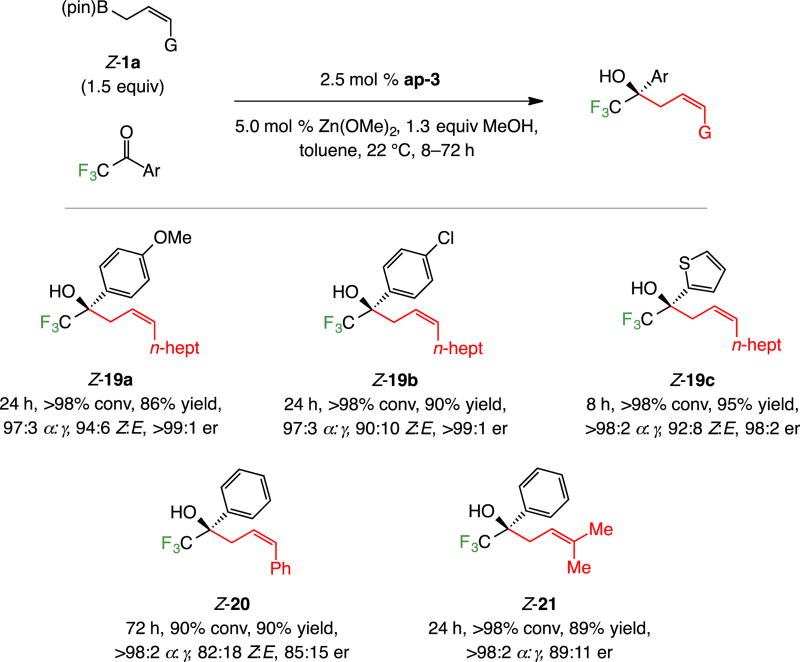

2.3. Reactions with other organoboron reagents.14

Transformations with n-heptyl-substituted Z-1a deliver products 19a–c efficiently (86–95% yield, Scheme 8), although in some cases longer reaction times were needed for complete conversion (24 h for 19a–b); Z selectivity ranged from 90–94% and α-selectivities and enantioselectivities remained high (97:3 to >98:2 and 98:2 to >99:1 er, respectively). With the larger E-phenyl-substituted (see 20, Scheme 8) and γ,γ’-dimethyl-substituted allyl–B(pin) compound (see 21), products were isolated in 89–90% yield but extended times were again required, especially in the former case (72 h); when the reaction was performed at 60 °C, there was complete conversion after six hours and the product was isolated in 90% yield, but selectivity levels were lower (92:8 α:γ, 76:24 Z:E, 80:20 er). Enantioselectivity was lower in the latter two instances (85:15 and 89:11 er, respectively), and 21 was formed with 82:18 Z:E selectivity.

Scheme 8.

Reactions with Other γ-Substituted Allylboron Reagentsa

aReactions carried out under N2 atm. Conv, α:γ and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields are for purified α-addition products (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). All experiments run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

2.4. Reactions with (E)-crotyl–B(pin)

The somewhat lower er for the reaction leading to prenyl alcohol 21 (Scheme 8) suggested that the corresponding transformation involving E-crotyl–B(pin) (E-1a, Scheme 9) might be less enantioselective: Z-3a was indeed generated in 91:9 er under the aforementioned conditions. The process was less efficient compared to when Z-1a was used (24 h vs 45 min for >98% conv); nonetheless, the expected homoallylic alcohol was isolated in 86% yield and with exceptional α:γ and Z:E ratios (>98:2).

Scheme 9.

Reactions with Crotylboron Compound E-1a: Substantial Variations in Enantioselectivitya

aReactions carried out under N2 atm. Conv, α:γ and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields for purified α-addition products (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). All experiments were run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

Transformations with E-1a and other trifluoromethyl ketones generated variable selectivity patterns (Scheme 9; compared to Z-1a, Scheme 4). With electron-rich aryl moieties enantioselectivity was moderate with preference for the same enantiomer as Z-1a (i.e., 3c in 85:15 vs >99:1 er). However, o-tolyl product 3b was formed in 44:56 er (vs >99:1 er with Z-1a). For o-bromophenyl alcohol 3e the opposite enantiomer was moderately favored (24:76 er vs 98:2 er with Z-1a). Remarkably, in the case of o-trifluoromethyl-substituted 3f there was near complete reversal of enantioselectivity (6:94 vs 98:2 er with Z-1a). High er (albeit moderate 85:15) in favor of the same major enantiomer as Z-1a was observed with m- and p-substituted products 3l and 3t and alkyl-substituted 11a (96:4 and 97:3 er, respectively). There were two other curious sets of data: (1) Z selectivity was high in all instances, except for o-tolyl-substituted 3b (83:17 vs 96:4 to >98:2 Z:E, respectively; Scheme 9). (2) There was reversal in the sense of enantioselectivity in the additions involving trifluoromethyl acetaldehyde compared to its di- and monofluoromethyl analogues (i.e., Z-3a vs Z-16a and Z-17a). Moreover, whereas addition to o-tolyl-substituted trifluoromethyl ketone led to the formation of Z-3b in nearly racemic form (44:56 er), the corresponding di- and monofluoromethyl derivatives Z-16b and Z-17b were generated in 9:91 and 4:96 er, respectively. The basis of these selectivity trends will be discussed below.

2.5. E- and Z-Organoboron compounds react via different intermediates

We began by examining why the same major enantiomer (in most cases) and Z olefin isomer (in all instances) were being formed, regardless of whether Z- or E-1a is used. One explanation could be rapid isomerization between the organoboron isomers. However, spectroscopic studies indicated that Z- or E-1a do not readily interconvert (<2% in the presence of 5.0 mol % Zn(OMe)2, 1.3 equiv MeOH, toluene-d8, 22 °C, 16 h).15 Moreover, reaction with rac-22 afforded 23a in 85:15 dr16 (Scheme 10; 84% yield, >98:2 α:γ, 92:8 er for the anti diastereomer, 91:9 er for the syn isomer). The stereochemical identity of the aforementioned products was ascertained by obtaining the X-ray structure of p-bromobenzoate derivative 24 (Scheme 10).13 These data indicate that each organoboron isomer reacts by a distinct pathway, as otherwise an equal mixture of syn and anti isomers would be formed (see below for further analysis).

Scheme 10.

Diastereo- and Enantioselective Additions with rac-22a

aReactions carried out under N2 atm. Conv, α:γ and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields for purified α-addition products (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). All experiments run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

2.6. Reactions with a racemic allylboron reagent

Aryl-, heteroaryl-, alkenyl and alkyl-substituted trifluoromethyl ketones may be used in diastereo- and enantioselective reactions with rac-22 (Scheme 10), although selectivity is moderate in some cases. This is a notable method because of the low catalyst loading (0.5 mol %), accessibility of the chiral catalyst, brief reaction times (1.5–3 h), mild conditions (22 °C), high yields, exceptional α selectivity and since, to the best of our knowledge, related catalytic enantioselective protocols have not been reported before. The organoboron compound (rac-22) can be accessed in a single step;15 with enantiomerically enriched 22, which can be synthesized by a number of methods,17 considerably higher stereoselectivity should be expected.15

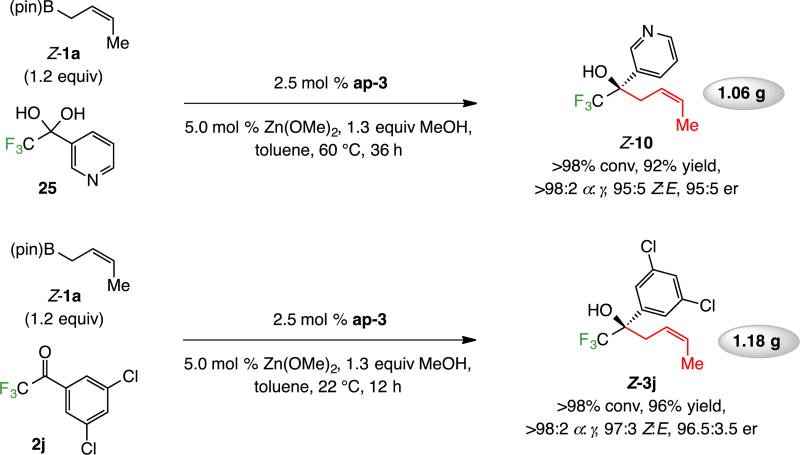

3. Utility

The method is amenable to gram scale operations (Scheme 11). The application to pyridine-substituted 10 again shows that a basic pyridine moiety is tolerated. The er with which 3j, precursor to anti-parasitic agent Bravecto™,18 (presently sold as the racemate) is formed in higher er than the addition of allyl–B(pin) (96.5:3.5 vs 95:5 er).10 It is especially notable that the gram-scale reaction shown in Scheme 11 were performed without exclusion of air and/or moisture.

Scheme 11.

Reactions on Gram Scalea

aReactions carried out without inert atmosphere. Conv, α:γ and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields for purified α-addition products (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). All experiments run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

The Z-homoallylic alcohols are suitable substrates for a variety of directed, highly diastereoselective transformations.19 Because the homoallylic ether products contain a Z-alkene, they can be readily converted to the corresponding Z-alkenyl halide derivatives through stereoretentive catalytic cross-metathesis reactions.20 The regarding stereoselective synthesis of alkenyl chloride 27 (Scheme 12) and its subsequent conversion to indole-containing 29 via boronic acid 28, is a case in point. The Z-1,2-substituted alkene is crucial to cross-metathesis efficiency.20 Reaction of the corresponding terminal alkene substrate was inefficient when a monoaryloxide pyrrolide complex was used (~40% conv, >98:2 Z:E)21 and did not afford any product with monoaryloxide chloride complex Mo-1.

Scheme 12.

In Combination with Catalytic Z-Selective Cross-Metathesisa

aConv and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields are for isolated and purified α-addition products (±5%). All experiments were run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

Another example (Scheme 12), performed with complex Ru-122 involves the use of an unprotected enantiomerically enriched tertiary alcohol (Z-3a) with commercially available unsaturated alcohol 30; the desired product (31) was obtained after eight hours at room temperature in 89% yield and >98:2 Z:E selectivity. Here, the presence of the Z-methyl-substituted alkenes is not only required for high efficiency, stereoselectivity is considerably higher compared to when a terminal alkenes is involved.23 Such transformations are valuable because, by a combination of catalytic cross-metathesis and cross-coupling reactions, a convenient route for the synthesis of otherwise difficult-to-access enantiomerically enriched compounds becomes feasible.

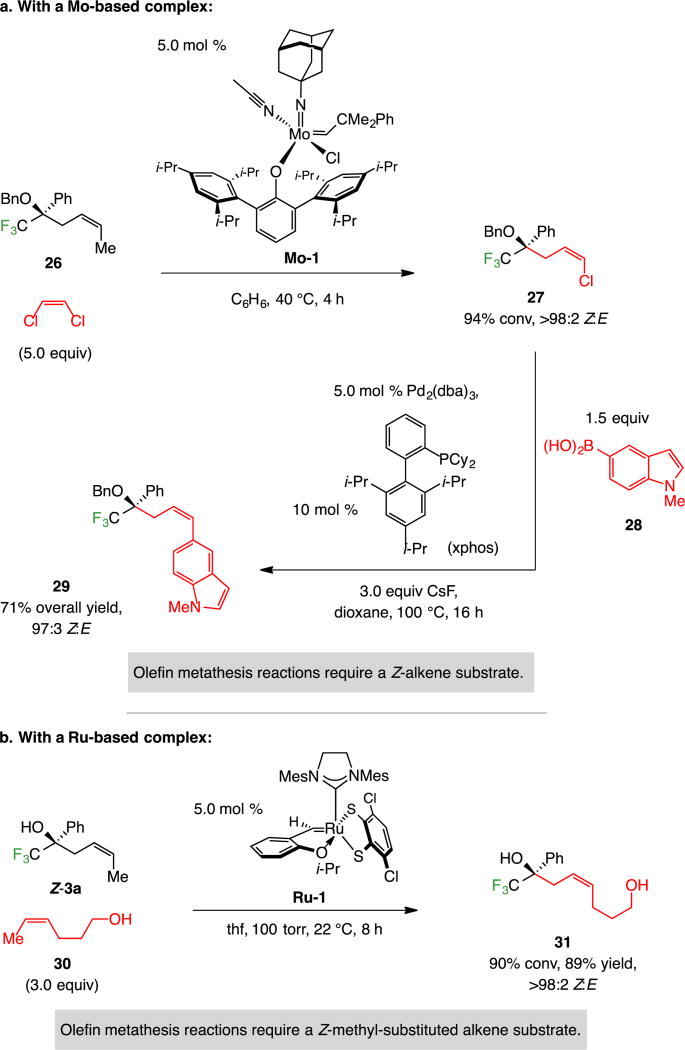

4. Stereochemical Models

4.1. For reactions with organoboron compound Z-1a

Based on DFT calculations (ωB97XD),15 the high enantioselectivity in the transformations with Z-1a is due to reaction via intermediate ix and complex I in preference to II (Scheme 13). In II there is electron–electron repulsion between the halogen atoms of the trifluoromethyl group and the catalyst’s aryloxide, and a near-eclipsing interaction between the methyl substituent and the catalyst’s B–O bond. Furthermore, coulombic attraction10 between the trifluoromethyl moiety and the catalyst’s ammonium group is only possible in I.10 Another competing mode of reaction, represented by III (Scheme 13), would deliver the same sense of enantioselectivity as I but with an E-alkene. As illustrated in III, the stabilizing coulombic attraction between the CF3 and the ammonium groups would be countered by two significant repulsive interactions.

Scheme 13.

Stereochemical Models Based on DFT Studies with Z-Crotyl–B(pin)a

aDFT calculations were performed at the ωB97XD/DEF2TZVPP//ωB97XD/DEF2SVPtoluene(SMD) level. Free energy values for transition states are relative to the most favorable alternative. See the Supporting Information for details.

Variations in aminophenol structure and the associated changes in Z selectivity and er, provide further insight (Table 1). While there is notable decrease in Z:E ratios with smaller catalyst substituents (97:3 to 83:17 to 84:16 with ap-3, ap-4 and ap-5, respectively), there is less significant diminution in er (99:1 to 98:2 to 97:3, respectively). As steric hindrance caused by the substrate’s phenyl group and the aminophenol substituent (G) is diminished in III, more of the E-alkene isomer is formed. In contrast, repulsion between the ketone’s trifluoromethyl group, which is smaller than Ph, and the same catalyst moiety, is not as significant and, therefore, the impact on er is less.

Table 1.

Effect of Ligand Structure on Stereoselectivity with Z-Crotyl–B(pin)a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| entry | G | time (h); conv (%)b |

α:γb | Z:Eb | yield (%)c | erd |

| 1 | SiPh3 (ap-3) | 1.5; >98 | >98:2 | 97:3 | 87 | 99:1 |

| 2 | t-Bu (ap-4) | 12; >98 | >98:2 | 83:17 | 85 | 98:2 |

| 3 | H (ap-5) | 48; 45 | >98:2 | 84:16 | 32 | 97:3 |

Reactions were carried out under N2 atm.

Determined through analysis of 19F NMR spectra of the unpurified product mixtures (±2%).

Yields are for isolated and purified α-addition products (±5%).

Er was determined through HPLC analysis (±1%). See the Supporting Information for details.

The lower enantioselectivities (81:19–85:15 er) for enyne 13a–c (Scheme 6) might be attributed to competing electrostatic attraction between the catalyst’s ammonium unit and the alkynyl group (IV). The slightly higher er for the more electron-poor p-trifluoromethylphenyl-substituted 13c (85:15 vs 81:19 er for 13a), provide some support but, together with nearly the same enantioselectivity for p-methoxyphenyl-substituted 13b, probably indicate that the change in electron density at the C–C triple bond is not significant enough for a more notable effect. Although interactions involving a C–C triple bond have been investigated only to a limited extent,24 related associations between an ammonium moiety and aryl groups have been examined extensively25 and proposed to account for the outcome of different types of transformations.26 Such interactions are unlikely to be as strong with the corresponding E-alkenes since a non-linear geometry should translate to less effective electrostatic attraction.

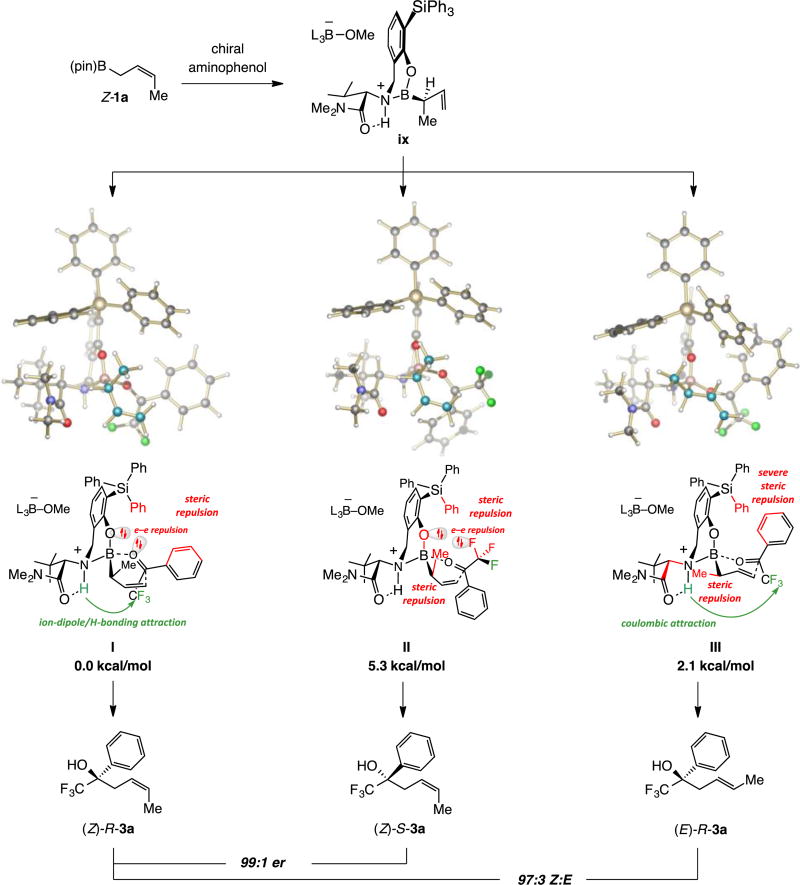

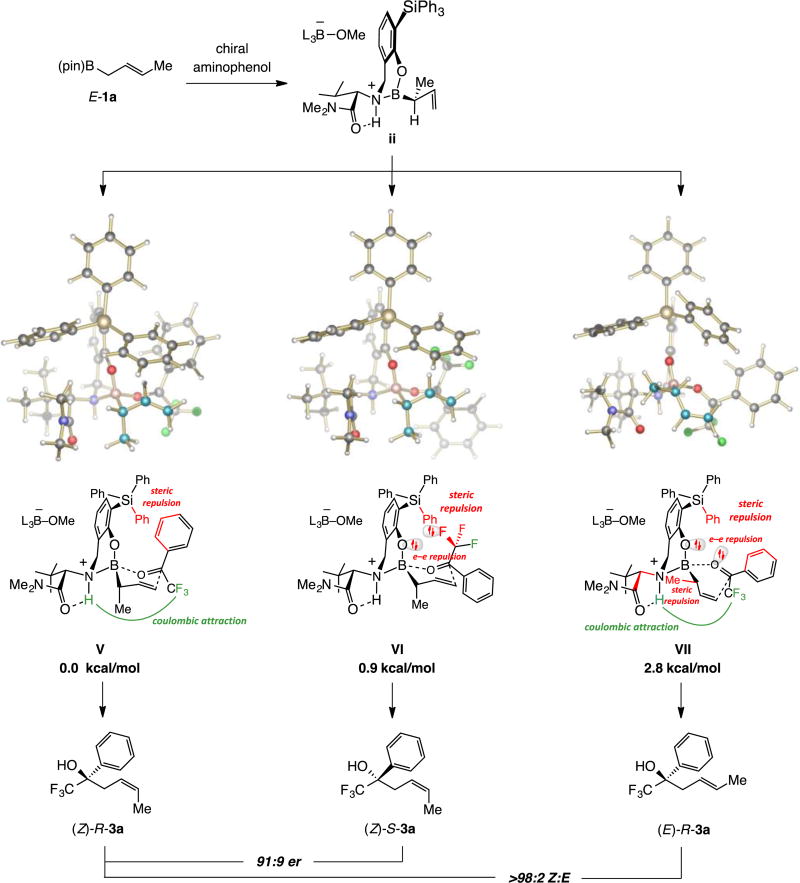

4.2. For reactions with organoboron compound E-1a

Enantioselectivities with E-crotyl–B(pin) are lower because of the smaller energy difference between V and VI (Scheme 14). The reason Z selectivity remains high in the reactions with E-1a is because of two counts of steric and electron–electron repulsion in VII, which render it less competitive. Reducing the size of the catalyst’s aryl substituent (G), as shown by the data in Table 2, diminishes Z selectivity to a small degree, suggesting that the electronic repulsion and steric interaction involving the psuedo-equatorial methyl group in VII is the stronger factor (i.e., repulsion between the ketone and Ph group of the triphenylsilyl unit is less influential, as indicated by the Z:E selectivity values). Analogous modification of catalyst structure has little impact on er (entries 1–3, Table 2), since there would likely be similar lowering of steric repulsion in V and VI. The preference for V is reflected in the adverse effect of a sizeable ortho aryl substituent on Z:E selectivity (e.g., 3e–f, Scheme 4), which arises from an increase in steric repulsion (vs VII wherein there is a pseudo-equatorial aryl moiety).

Scheme 14.

Stereochemical Models Based on DFT Studies with E-Crotyl–B(pin)a

aDFT calculations were performed at the ωB97XD/DEF2TZVPP//ωB97XD/DEF2SVPtoluene(SMD) level. Free energy values for transition states are relative to the most favorable alternative. See the Supporting Information for details.

Table 2.

Effect of Ligand Structure on Stereoselectivity with E-Crotyl–B(pin)a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| entry | G | time (h); conv (%)b |

α:γb | Z:Eb | yield (%)c | erd |

| 1 | SiPh3 (ap-3) | 24; >98 | >98:2 | >98:2 | 86 | 91:9 |

| 2 | t-Bu (ap-4) | 24; >98 | >98:2 | 97:3 | 84 | 93:7 |

| 3 | H (ap-5) | 24; 71 | >98:2 | 96:4 | 60 | 89:11 |

Reactions were carried out under N2 atm.

Determined through analysis of 19F NMR spectra of the unpurified product mixtures (±2%).

Yields are for isolated and purified α-addition products (±5%).

Er was determined through HPLC analysis (±1%). See the Supporting Information for details.

4.3. For reactions with di- and monofluoromethyl ketones

We have previously shown that electrostatic attraction with the catalyst’s ammonium site is less influential with di- and monofluoromethyl ketones.10 When Z-1a was used, products such as difluoromethyl 16a and monofluoromethyl 17a were generated in high er, indicating that reaction via VIII is more favored (vs IX, Scheme 15a). This is in contrast to allyl–B(pin) additions to the same ketones because with the presence of the methyl substituent steric factors become more influential such that high er can be attained. On the other hand, Z selectivity hinges on competition between VIII and X (Scheme 15a), involving addition to different enantiotopic faces of the ketone carbonyl, as confirmed through determination of absolute stereochemistry.15 The lower Z:E ratios thus reflect the lower energy difference between the steric hindrance of the ketone substituent and the triphenylsilyl group in VIII as well as the pseudo-equatorial methyl group and the catalyst framework in X. The slightly higher Z selectivity for difluoromethyl ketones (vs the monofluoromethyl derivative) might be the result of stronger electrostatic attraction between the fluoro-organic moiety and the ammonium group.

Scheme 15.

Influence of Number of Fluorine Atoms on Stereoselectivitya

aReactions carried out under N2 atm. Conv, α:γ and Z:E ratios determined by analysis of 19F NMR spectra of unpurified product mixtures (±2%). Yields are for purified α-addition products (±5%). Er determined by HPLC analysis (±1%). All experiments run in duplicate or more. See the Supporting Information for details.

The sense of enantioselectivity is reversed with E-1a (Scheme 15b) because the reactions proceed via XI and XII. Without electrostatic attraction, XII is favored due to lower steric repulsion, a distinction more pronounced with a smaller monofluoroalkyl substituent (22:78 vs 9:91 er for 16a and 17a, respectively; Scheme 15b). It follows that with a more sterically demanding aryl substituent, XI becomes less favored, resulting in increased enantioselectivity to the extent that o-trifluoromethyl-substituted 3f may be generated in 6:94 er (Scheme 9).

Conclusions

We put forth methods for efficient and enantioselective addition of readily accessible Z-γ-substituted boronic acid pinacol ester compounds to fluoroalkyl-substituted ketones. The approach has considerable range as aryl-, heteroaryl-, alkynyl-, alkenyl- and alkyl-substituted ketones with a polyfluoro-, trifluoro-, difluoro- and monofluoro-alkyl substituent can be used, affording products with up to 98% yield and >99:1 er (Schemes 4–8). Reactions can be catalyzed by 0.5–2.5 mol % of a complex generated in situ from valine-derived aminophenol ligand, may be carried out at room temperature, and are complete within a few hours. Contrary to reactions with unsubstituted allyl–B(pin), additions to mono- and difluoroalkyl substituted ketones are highly enantioselective. A noteworthy aspect of the transformations is that addition of the initial chiral organoboron intermediate to a fluoro-ketone is faster than 1,3-boryl shift, and as a result, α selectivity is often exceptionally high. Equally notable are the high Z:E ratios (up to >98:2), an attribute that is largely due to effective catalyst control of stereoselectivity. The assortment of possibilities for functionalization of the stereochemically defined alkene product, such as kinetically controlled Z-selective olefin metathesis reactions, add to the value of the approach.

We provide the first examples of efficient, diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of the corresponding γ-addition type products, where a racemic organoboron reagent adds to various fluoroketones with >98% α selectivity (Scheme 12). Thus, by a combination of electronic (e.g., electrostatic attraction between catalyst’s ammonium group and the fluoroalkyl groups) and steric factors (e.g., induced by installation of a sizeable triphenylsilyl group) a variety of tertiary homoallylic alcohols that contain a stereogenic carbon center with a hydroxyl and a fluoroalkyl substituent may be prepared in high yield, high Z-selectivity and high enantiomeric purity. Mechanistic models based on DFT studies provide a rationale for different selectivity profiles and should be of value in future studies regarding this class of enantioselective catalysts (Schemes 13–15, Tables 1–2).

The present advance allows facile access to many valuable enantiomerically enriched organofluorine compounds that might be used in the preparation of therapeutic candidates, novel materials and/or more effective agrochemicals. Design and development of additional boron-based chiral catalysts and methods for enantioselective synthesis continue in these laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the NIH and the NSF (GM-57212 and in part GM-59426 and CHE-1362763). We are grateful to KyungA Lee, Thach T. Nguyen, Ming Joo Koh, Sebastian Torker and Chaofan Xu for valuable advice and support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available.

Experimental details for all reactions and analytic details for all enantiomerically enriched products. Tables of electronic and free energies and geometries of computed structures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Gillis EP, Eastman KJ, Hill MD, Donnelly DJ, Meanwell NA. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:8315–8359. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujiwara T, O’Hagan D. J. Fluorine Chem. 2014;167:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger R, Resnati G, Metrangolo P, Weber E, Hulliger J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:3496–3508. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00221f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Loh TP, Zhou J-R, Li X-R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:9333–9336. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang X, Chen D, Liu X, Feng X. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:5227–5233. doi: 10.1021/jo0706325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Haddad TD, Hirayama LC, Taynton P, Singaram B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:508–511. [Google Scholar]

- 5.For recent reviews on enantioselective synthesis through additions of allyl groups to ketones and imines and their applications, see: Yus M, González-Gómez JC, Foubelo F. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:7774–7854. doi: 10.1021/cr1004474.For corresponding diastereoselective processes, see: Yus M, González-Gómez JC, Foubelo F. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:5595–5698. doi: 10.1021/cr400008h.

- 6.For catalytic enantioselective additions of allyl moieties to ketones (without proximal fluorine substituents), see: Kii S, Maruoka K. Chirality. 2003;15:68–70. doi: 10.1002/chir.10163.Wada R, Oisaki K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8910–8911. doi: 10.1021/ja047200l.Kim JG, Waltz KM, Garcia IF, Kwiatkowski D, Walsh PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12580–12585. doi: 10.1021/ja047758t.Wadamoto M, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14556–14557. doi: 10.1021/ja0553351.Thornqvist V, Manner S, Frejd T. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2006;17:410–415.Miller JJ, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2752–2753. doi: 10.1021/ja068915m.Lou S, Moquist PN, Schaus SE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12660–12661. doi: 10.1021/ja0651308.Barnett DS, Moquist PN, Schaus SE. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:8679–8682. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904715.Haddad TD, Hirayama LC, Taynton P, Singaram B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:508–511.Huang X-R, Chen C, Lee G-H, Peng S-M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:3089–3095.Shi S-L, Xu L-W, Oisaki K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6638–6639. doi: 10.1021/ja101948s.Zhang Y, Li N, Qu B, Ma S, Lee H, Gonnella NC, Gao J, Li W, Tan Z, Reeves JT, Wang J, Lorenz JC, Li G, Reeves DC, Premasiri A, Grinberg N, Haddad N, Lu BZ, Song JJ, Senanayake CH. Org. Lett. 2013;15:1710–1713. doi: 10.1021/ol400498a.Robbins DW, Lee K, Silverio DL, Volkov A, Torker S, Hoveyda AH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:9610–9614. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603894.

- 7.For examples of catalytic enantioselective additions of C-based nucleophiles to trifluoromethyl ketones (with no secondary chelating group), see: Zhang G-W, Meng W, Ma H, Nie J, Zhang W-Q, Ma J-A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:3538–3542. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007341.Motoki R, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2997–3000. doi: 10.1021/ol071003k.Cook AM, Wolf C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:2929–2933. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510910.Noda H, Amemiya F, Weidner K, Kumagai N, Shibasaki M. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:3260–3269. doi: 10.1039/c7sc00330g.Zheng Y, Tan Y, Harms K, Marsch M, Riedel R, Zhang L, Meggers E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:4322–4325. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01098.

- 8.(a) Silverio DL, Torker S, Pilyugina T, Vieira EM, Snapper ML, Haeffner F, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2013;494:216–221. doi: 10.1038/nature11844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu H, Haeffner F, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:3780–3783. doi: 10.1021/ja500374p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For a recent overview regarding applications of allylboron reagents in chemical synthesis, see: Diner C, Szabó K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:2–14. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10017.

- 10.(a) Lee K, Silverio DL, Torker S, Robbins DW, Haeffner F, van der Mei FW, Hoveyda AH. Nature Chem. 2016;8:768–777. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mszar NW, Mikus MS, Torker S, Haffner F, Hoveyda AH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Mei FW, Miyamoto H, Silverio DL, Hoveyda AH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:4701–4706. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For leading studies regarding the mechanism of 1,3-boryl shift processes, see: Hancock KG, Kramer JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:6463–6465.Hancock KG, Kramer JD. J. Organomet. Chem. 1974;64:C29–C31.Henriksen U, Snyder JP, Halgren TA. J. Org. Chem. 1981;46:3767–3768.Bühl M, von Ragué Schleyer P, Ibrahim MA, Clark T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:2466–2471.Bubnov YN, Gurskii ME, Gridnev ID, Ignatenko AV, Ustynyuk YA, Mstislavsky VI. J. Organomet. Chem. 1992;424:127–132.

- 13.See the Supporting Information for details of X-ray structures.

- 14.The organoboron compounds used to prepare 20a–c and 21 were prepared according to previously reported procedures. See: Ely RJ, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2534–2535. doi: 10.1021/ja910750b.Zhang P, Roundtree IA, Morken JP. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1416–1419. doi: 10.1021/ol3001552.The trisubstituted boronate used to synthesize 22 is commercially available. See the Supporting Information for further details.

- 15.See the Supporting Information for details.

- 16.The reason for the 85:15 dr is that, as indicated by investigations details of which can be found in the Supporting Information, reaction of R- and S-24 afford the same anti-25a predominantly but with different levels of diastereo- and enantioselectivity.

- 17.For synthesis of allylboron compounds by catalytic enantioselective methods, see: Ito H, Ito S, Sasaki Y, Matsuura K, Sawamura M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14856–14857. doi: 10.1021/ja076634o.Guzman-Martinez A, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10634–10637. doi: 10.1021/ja104254d.Ito H, Okura T, Matsuura K, Sawamura M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:560–563. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905993.Ito H, Kunii S, Sawamura M. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:972–976. doi: 10.1038/nchem.801.Park JK, Lackey HH, Ondrusek BA, McQuade DT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2410–2413. doi: 10.1021/ja1112518.Park JK, McQuade DT. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:2717–2721. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107874.Potter B, Edelstein EK, Morken JP. Org. Lett. 2016;18:3286–3289. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01580.

- 18.Kaiser F, Körber K, Von Deyn W, Deshmukh P, Narine A, Dickhaut J, Bandur NG, Langewald J, Culbertson DL, Anspaugh DD. WO 2012/007426 A1. International Patent. 2011 Jul 11; filed, issued 19 Jan 2012.

- 19.Hoveyda AH, Evans DA, Fu GC. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1307–1370. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koh MJ, Nguyen TT, Lam JK, Torker S, Hyvl J, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2017;542:80–85. doi: 10.1038/nature21043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koh MJ, Nguyen TT, Zhang H, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2016;531:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nature17396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koh MJ, Khan RKM, Torker S, Yu M, Mikus MS, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2015;517:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature14061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu C, Shen X, Hoveyda AH. unpublished results. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramachandran PV, Gong B, Teodorovic AV, Brown HC. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1994;5:1061–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Dougherty DA. Science. 1996;271:163–168. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ma JC, Dougherty DA. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:1303–1324. doi: 10.1021/cr9603744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mahadevi AS, Sastry GN. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:2100–2138. doi: 10.1021/cr300222d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Holland MC, Metternich JB, Mück-Lichtenfeld C, Gilmour R. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:5322–5325. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08520e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kamps JJAG, Khan A, Choi H, Lesniak RK, Brem J, Rydzik AM, McDonough MA, Schofield CJ, Claridge TDW, Mecinović J. Chem. Eur. J. 2016;22:1270–1276. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Yamada S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:2903–2912. doi: 10.1039/b706512b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yao L, Aubé J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2766–2767. doi: 10.1021/ja068919r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Knowles RR, Lin S, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5030–5032. doi: 10.1021/ja101256v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yamada S, Fossey JS. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:7275–7281. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05228d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hori M, Sakakura A, Ishihara K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13198–13201. doi: 10.1021/ja508441t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.