Abstract

Estrogen (E2) signaling through its nuclear receptor, E2 receptor α (ERα) increases insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF1) in the rodent uterus, which then initiates further signals via the IGF1 receptor. Directly administering IGF1 results in similar biological and transcriptional uterine responses. Our studies using global ERα-null mice demonstrated a loss of uterine biological responses of the uterus to E2 or IGF1 treatment, while maintaining transcriptional responses to IGF1. To address this discrepancy in the need for uterine ERα in mediating the IGF1 transcriptional vs growth responses, we assessed the IGF1 transcriptional responses in PgrCre+Esr1f/f (called ERαUtcKO) mice, which selectively lack ERα in progesterone receptor (PGR) expressing cells, including all uterine cells, while maintaining ERα expression in other tissues and cells that do not express Pgr. Additionally, we profiled IGF1-induced ERα binding sites in uterine chromatin using chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing. Herein, we explore the transcriptional and molecular signaling that underlies our findings to refine our understanding of uterine IGF1 signaling and identify ERα-mediated and ERα-independent uterine transcriptional responses. Defining these mechanisms in vivo in whole tissue and animal contexts provides details of nuclear receptor mediated mechanisms that impact biological systems and have potential applicability to reproductive processes of humans, livestock and wildlife.

After treatment with IGF1, we compared transcriptional profiles of wild-type and ERα null tissues to ERα ChIP-seq data to find ER-α–independent and ER-α–dependent uterine responses to IGF1.

Estrogen (E2) signaling through the activity of the E2 receptor α (ERα) is essential in the rodent uterus for the establishment of pregnancy. ERα can be detected in the three main cell types within the uterus: epithelial cells, myometrial cells, and stromal cells. Epithelial cells line the lumen and the glands emanating from the lumen, the myometrial layers wrap around the exterior of the uterine tube, and the stromal cells are between the epithelial and myometrial layers. In sexually mature ovariectomized animals, E2 initiates proliferation specifically of the epithelial cell layer, leading ultimately to a transition of the single layer of cuboidal cell epithelium into a hypertrophied hyperplastic secretory layer. Studies by Cooke and colleagues (1), using recombination of isolated immature uterine cells, indicated the importance of the ERα in stromal cells in this response and described a mechanism in which stromal cell ERα induces mitogenic signals, later shown to be growth factors, which act in a paracrine manner to activate epithelial cell growth factor receptor signaling (2). Studies using adult Wnt7aCre mice to selectively delete ERα in uterine epithelial cells (Wnt7aCre+;Esr1f/f, called ERαEpicKO) further confirmed this mechanism in an adult in situ tissue, as E2 could still induce uterine epithelial cell growth (3).

Several candidate mitogenic factors have been studied as mediators of the paracrine growth response. Insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF1) is one candidate, considering E2 induces its transcript as well as the protein, primarily in stromal cells (2, 4). In addition, epithelial cells have IGF1 receptors (IGF1Rs), and evidence for activation of uterine IGF1R signaling is observed following E2 treatment (5). IGF1-null mice lack a full uterine epithelial growth response to E2 (6) and directly administering IGF1 to mice induces uterine epithelial cell growth (7). The absence of uterine epithelial growth response in global ERα-null mice (called α-ERKO or Ex3αERKO) following IGF1 treatment indicates a direct role for ERα in mediating the IGF1 signal (7, 8). These findings led us to a model in which IGF1R signals “cross-talk” to the ERα, resulting in E2-like ERα-mediated responses. The global ERα-null models have additional phenotypes, such as obesity and insulin resistance, related to loss of E2 signaling in all tissues, that might impact uterine responsiveness. To more specifically address the role of uterine ERα in mediating the IGF1 response, we assessed the IGF1 transcriptional responses in PgrCre+;Esr1f/f (called ERαUtcKO) mice, which selectively lose ERα from progesterone receptor (PGR) expressing cells, including all uterine cells, while maintaining ERα expression in other tissues and cells. Herein, we explore the transcriptional and molecular signaling within wild-type (WT) and ERα-null contexts that underlies our findings to refine our understanding of IGF1 signaling in uterine transcriptional responses.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All mice were handled in accordance with protocols approved by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Animal Care and Use Committee in compliance with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals (9). In this study, Ex3αERKO mice used as a global ERα-null model and WT control littermates were bred from our contract colony (Taconic Biosciences, Albany, NY) and uterine ERα-null mice (PgrCre+;Esr1f/f or ERαUtcKO) were bred from an NIEHS colony. Both colonies were genotyped by Transnetyx Inc. (Cordova, TN). Eight weeks or older female Ex3αERKO or ERαUtcKO mice and their WT littermates were ovariectomized and rested for 10 to 14 days to clear endogenous ovarian hormones. Animals were randomly divided into treatment groups: estradiol (i.e., E2; Research Plus Inc., Barnegat, NJ; 250 ng/100 μL saline) or normal saline vehicle (V) was administered by intraperitoneal injection, and uterine tissue was collected 2 or 24 hours later. IGF1 (Recombinant Human LR3 IGF1; Cell Sciences, Newburyport, MA) was either given by intraperitoneal injection (50 μg in 100 μL phosphate-buffered saline) and uterine tissue was collected after 1 or 2 hours, or for longer treatment, IGF1 was administered using an Alzet model 1003D osmotic pump (Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA) filled with 100 μL 0.5 mg IGF1/mL 0.1 N acetic acid and uterine tissue was collected 24 hours later. The ERα antagonist ICI 182,780 was administered by intraperitoneal injection (Tocris Biosciences, Bristol, UK, 45 μg/50 μL DMSO) 30 minutes prior to V, E2, or IGF1 injection to a subgroup of WT mice. In the case of V and 24-hour samples, a piece of the uterine sample was fixed in 10% formalin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) for further analysis. The remaining uterine tissue as well as 2-hour samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and processed for RNA extraction using Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described (10). RNA was used for real-time (RT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or microarray. Additional ovariectomized WT mice were collected 1 hour after intraperitoneal injection of V, E2, IGF1, or ICI; snap frozen; and sent to Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA) for ERα chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) sequencing (seq) or ChIP-PCR analyses.

Immunohistochemistry

Uterine tissue was embedded in paraffin, cut into 4-μM sections onto charged slides. Sections were deparrafinized, decloaked in a Biocare Decloaking Chamber with Biocare 1× Antigen Decloaking Buffer (Biocare Medical, Pacheco, CA) and blocked with 5% H2O2. Sections were blocked with 10% Normal Horse Serum (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) then incubated with mouse antihuman Ki-67 [BD Pharmingen/BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA; Catalog No. 550609; research resource identifier (RRID): AB_393778] diluted 1:100 or anti-ERα (Biocare Medical ER- 1D5 Catalog No. ACA 054C, RRID: AB_2651037) 1:200 in 10% Normal Horse Serum and developed with biotinyl-anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and Extravidin Peroxidase (Sigma Chemical St Louis MO) and Dako Products DAB (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

RT-PCR

Complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 to 2 µg of uterine RNA as previously described (10), diluted 1:100 in water, and analyzed by RT-PCR using Fast Sybr Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Isle, NY) and primers to transcripts of interest (synthesized by Sigma Genosys, The Woodlands, TX; sequences in Supplemental Table 2 (3.3MB, pdf) ) as previously described (10).

Microarray and data analysis

Isolated RNA was further cleaned up using the Qiagen RNeasy Kit clean-up protocol with DNase treatment (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and submitted to the NIEHS Microarray Group/Molecular Genetics Core for analysis using the Affymetrix Mouse Whole Transcriptome Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Data were analyzed using Partek Genomics Suite 6.6 (Partek Inc., St. Louis, MO) and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Qiagen). Microarray data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database accession number GSE100131.

ChIP-seq and ChIP-PCR

Uterine tissue was shipped to Active Motif Inc. for ERα ChIP-seq or ChIP-PCR. ChIP-seq libraries were sequenced either single-end 36-mers or single-end 50-mers; for consistency, all reads were trimmed to 36-nt as the first step of data processing. The raw sequence reads were then filtered to remove any entries with a mean base quality score <20. Reads were mapped against the mm10 reference genome via Bowtie (v0.12.8) (11), with only uniquely mapped hits accepted. Duplicate mapped hits were removed with Picard tools MarkDuplicates.jar (v1.110). Peak calls were made by HOMER (v4.7.2) (12) with parameters “-fdr 0.00001 -F 12 -style factor.” For consistency across datasets, each HOMER peak was redefined as a 200-nt region centered on the midpoint of the called peak. An overlap analysis was performed between peak sets, where two peaks must share a minimum of 100-nt to be considered overlapping. Peaks were assigned to gene loci according to the closest transcription start site (TSS) with maximum distance of 50 kb, considering only genes that are expressed in mouse uterus. Genes qualified as “expressed” if they had an average fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped of at least 0.5 in V-treated or E2-treated RNA-seq samples (unpublished data). The gene models used for this analysis are based on RefSeq as downloaded from the University of California, Santa Cruz Genome Browser on 9 February 2015. Data are deposited in the GEO database accession number GSE100023.

Statistical analysis

Values were compared using statistical tools in Graphpad Prism 7. Two-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons using Fisher’s least significant difference.

Results

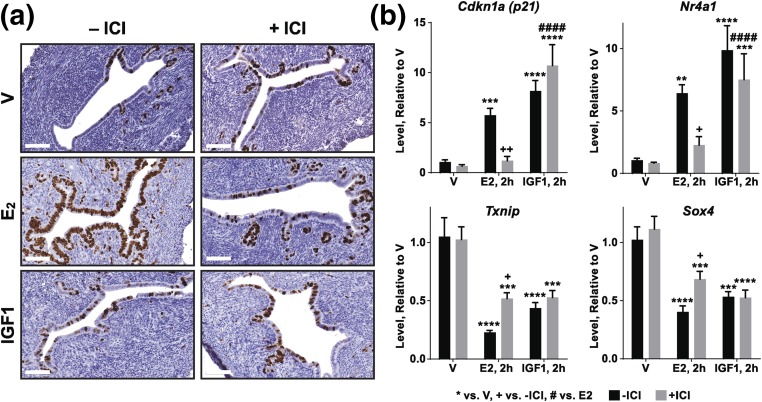

Previously, we reported that global ERα-null (α-ERKO and Ex3αERKO) females lacked uterine growth following IGF1 treatment (7, 8). Analysis indicated that IGF1R was present in ERα-null uterine tissue (7). IGF1R-mediated signaling was intact as shown by increased phosphorylation of uterine IGF1R, AKT, and mitogen-activated protein kinase, and association of IRS1 and P85 with the IGF1R following IGF1 treatment of ERα-null mice (7). To directly test the effect of ERα signaling on uterine IGF1 response, the ERα antagonist ICI 182,780 (ICI; fulvestrant) was administered to WT mice 30 minutes prior to E2 or IGF1 treatments. ICI effectively inhibited E2 response, but did not impair IGF1 induction of uterine epithelial cell growth as reflected by increase in the Ki67 protein [Fig. 1(a)]. We previously reported that some E2 responsive uterine transcripts can also be regulated by IGF1 (13). Evaluation of four uterine transcripts that we have previously characterized as E2 or IGF1 regulated (13) by RT-PCR indicates that the E2 induction of cyclin-dependent kinase 1a (Cdkn1a) and nuclear receptor 4a1 (Nr4a1) was inhibited by ICI, and the E2 repression of thioredoxin-interacting protein (Txnip) and Sry-Box4 (Sox4) was partly inhibited by ICI. However, the IGF1 responses tested in WT mice were not inhibited by ICI [Fig. 1(b)]. The inability of ICI to inhibit uterine growth or gene regulation suggests that ERα is not required for IGF1-mediated responses in the WT context, where ERα is present.

Figure 1.

ERα antagonist does not inhibit IGF1-induced uterine growth or gene regulation. (a) Ki67 proliferative marker immunohistochemistry of uterine samples from WT mice treated for 24 hours with saline V, E2, or IGF1 either alone (–ICI) or in combination with the ERα antagonist ICI 182,780 (+ICI). Scale bars = 60 µM. (b) RT-PCR shows that transcripts that are induced (Cdkn1a, Nr4a1) or repressed (Txnip, Sox4,) by E2 (2 hours) are also regulated by IGF1 (2 hours). ICI inhibits the E2-mediated upregulation, and partially inhibits the E2-mediated downregulation, but does not affect the IGF1-mediated regulation. Black bars: no ICI; gray bars: with ICI. Two-way analysis of variance with posttest *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs V; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01 no ICI vs with ICI; #### P < 0.0001 E2 vs IGF1. N = 4 or 5 for all samples.

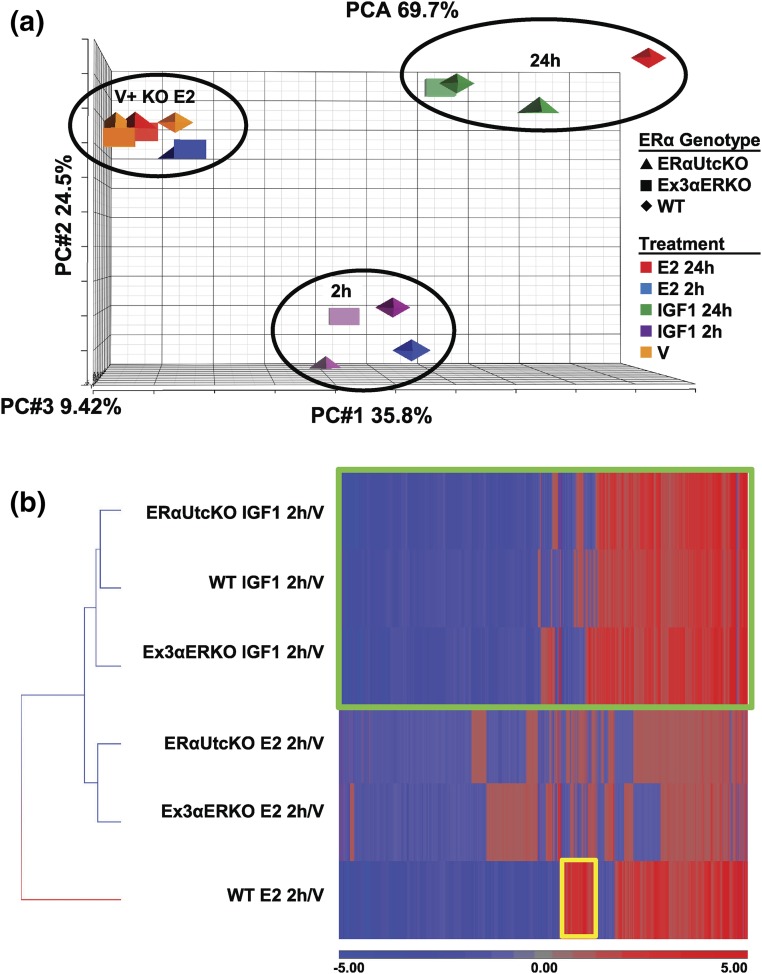

To address this discrepancy in the necessity for ERα in uterine responses to IGF1, we assessed mechanisms mediating IGF1-induced transcriptional responses in ERα-null vs ERα-containing contexts. We evaluated transcriptional profiles of uterine tissue from ovariectomized WT and Ex3αERKO mice following E2 or IGF1 treatments. In addition, we evaluated uterine RNA samples from mice with uterine selective ERα deletion (ERαUtcKO), following E2 or IGF1 treatments. The ERαUtcKO mouse was made by crossing Esr1f/f mice with PgrCre+ mice. These mice have deletion of ERα in all PGR expressing cells, including all uterine cells (Supplemental Fig. 1 (3.3MB, pdf) ). Treatment groups as well as the number of samples in each treatment group evaluated by microarray are summarized in Supplemental Table 1 (3.3MB, pdf) . Principle component analysis of the sample means revealed three groupings of samples [Fig. 2(a)] that reflect several conclusions. First, that both ERα-null models treated with E2 (KO E2) clustered together with all the V-treated samples, indicating lack of transcriptional response to E2 in the ERαUtcKO and Ex3αERKO, as expected. That is, the ERα-null models, when treated with E2, do not yield a transcriptional response, hence the sample means cluster together with V-treated samples from all genotypes. The second group included WT samples treated for 2 hours with E2 or IGF1, indicating that IGF1 and E2 elicit similar transcriptional responses. Additionally, ERαUtcKO and Ex3αERKO samples treated with IGF1 for 2 hours were in this group, showing that the IGF1 response is similar and indicating ERα independence of the overall transcriptional response. Similarly, the third group contained WT samples treated for 24 hours with E2 or IGF1 together with ERαUtcKO and Ex3αERKO samples treated with IGF1 for 24 hours. The same grouping is evident in a hierarchically clustered heatmap of the 12,000 differentially expressed (DE; less than twofold, false discovery rate < 0.05) transcripts (Supplemental Fig. 2 (3.3MB, pdf) ). Like our previous findings (13), the patterns of gene expression following E2 or IGF1 are similar to each other in WT, and the IGF1 response also occurs in Ex3αERKO. In addition, we now observe IGF1 responses in ERαUtcKO samples. Consistent with our previous report (13), WT responses to E2 include some transcripts that are not impacted by IGF1 [Supplemental Fig. 2 (3.3MB, pdf) ; Fig. 2(b), yellow boxes]. E2 treatment increases IGF1 synthesis and IGF1R-mediated signaling in uterine tissue, with a peak of Igf1 transcript occurring 4 to 6 hours after E2 is administered (14), and subsequent IGF1R activation observed 6 to 24 hours after E2 treatment (15). Because of this, the responses observed 24 hours following E2 will be affected by induction of IGF1 signals. Therefore, we focused on the transcriptional responses 2 hours after E2 or IGF1 treatments to find responses without the influence of secondary IGF1R-mediated signals; 7500 transcripts were differentially expressed in response to 2 hours IGF1 or E2 [Fig. 2(b)].

Figure 2.

Microarray analysis of E2- and IGF1-regulated transcripts. (a) Principal component analysis of all sample means from WT (diamond), ERαUtcKO (triangle), and Ex3αERKO (square) uterine RNA from V, E2, or IGF1 treatments for 2 hours or 24 hours. Red = E2 (24 hours), blue = E2 (2 hours), green = IGF1 (24 hours), purple = IGF1 (2 hours), orange = V. Numbers of each sample are detailed in Supplemental Table 1 (3.3MB, pdf) . (b) Hierarchical cluster of DE (intensity >100, twofold, false discovery rate <0.05) probes. Green box, probes DE by IGF1; yellow box, probes DE only by E2.

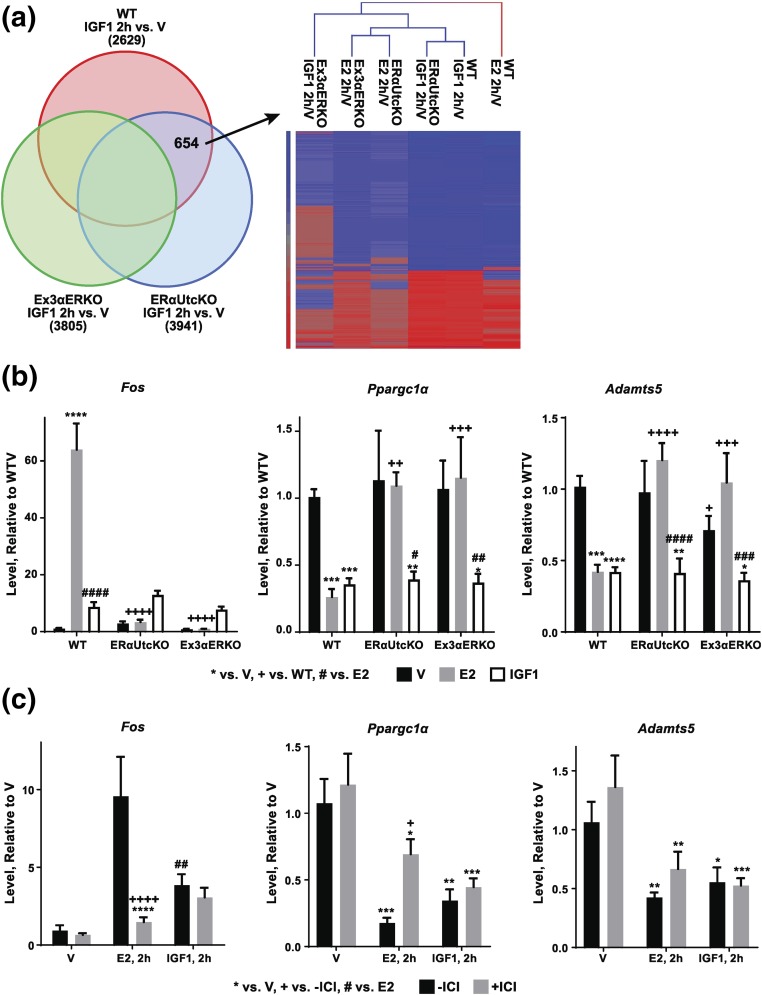

Probes (654 total, 262 for coding RNA) that might reflect IGF1 response independent of ERα were selected from a comparison of genes DE after IGF1 treatment of WT and ERαUtcKO mice while excluding those DE after IGF1 treatment of Ex3αERKO mice [Fig. 3(a)]. Although Ex3αERKO IGF1 responses are also ERα-independent and are similar to WT and ERαUtcKO responses, we focused on WT and ERαUtcKO responses to minimize effects that global ERα deletion might have on the uterine tissue responsiveness. Enriched biological functions associated with these 654 DE genes [Supplemental Fig. 3(a (3.3MB, pdf) )] include activation of transcription and cell survival, and suppression of cell death. Additionally, the regulation pattern of the 654 transcripts is consistent with activation of various receptor-mediated tyrosine kinase signals, including transforming growth factor-β1 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Three transcripts [FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene (Fos), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-α (Ppargc1α), and a disintegrin-like and metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 5 (Adamts5)] selected from the 654 ERα-independent probes were verified using RT-PCR. All three transcripts were regulated by E2 in WT samples, and Adamts5 and Ppargc1α were regulated by IGF1 treatment of both WT and ERα-null mice [Fig. 3(b)]. Fos was increased by IGF1 treatment in WT and ERα-null samples; however, the induction did not reach significance. RT-PCR findings indicate that Adamts5 and Ppargc1α are regulated by IGF1 in Ex3αERKO, despite exclusion of Ex3αERKO IGF1 responses when the ERα-independent transcripts were selected using the analysis in Fig. 3(a). This pattern is, however, consistent with ERα-independent regulation of these uterine transcripts by IGF1. ICI did not inhibit regulation of these transcripts by IGF1 in WT mice [Fig. 3(c)], also indicative of ERα independence.

Figure 3.

ERα-independent transcriptional responses. (a) Left: Venn diagram showing selection of 654 ERα-independent probes from overlap of transcripts DE by IGF1 in WT and ERαUtcKO, but not Ex3αERKO. Right: Hierarchical cluster of the 654 transcripts. (b) RT-PCR showing IGF1 (2 hours) regulation of Fos, Ppargc1a, and Adamts5 is ERα independent. Black = V, gray = E2, white = IGF1. Two-way analysis of variance with posttest. *P < 0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001 vs V; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001, ++++P <0.0001 vs WT; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 E2 vs IGF1. N = 3 to 7 for all samples. (c) ICI does not inhibit IGF1 (2 hours) regulation of Fos, Ppargc1a, and Adamts5 consistent with an ERα-independent mechanism. Black = no ICI, gray = with ICI. Two-way analysis of variance with posttest *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs V; +P < 0.05, ++++P < 0.0001 no ICI vs with ICI; ##P < 0.01 E2 vs IGF1. N = 4 to 5 for all samples.

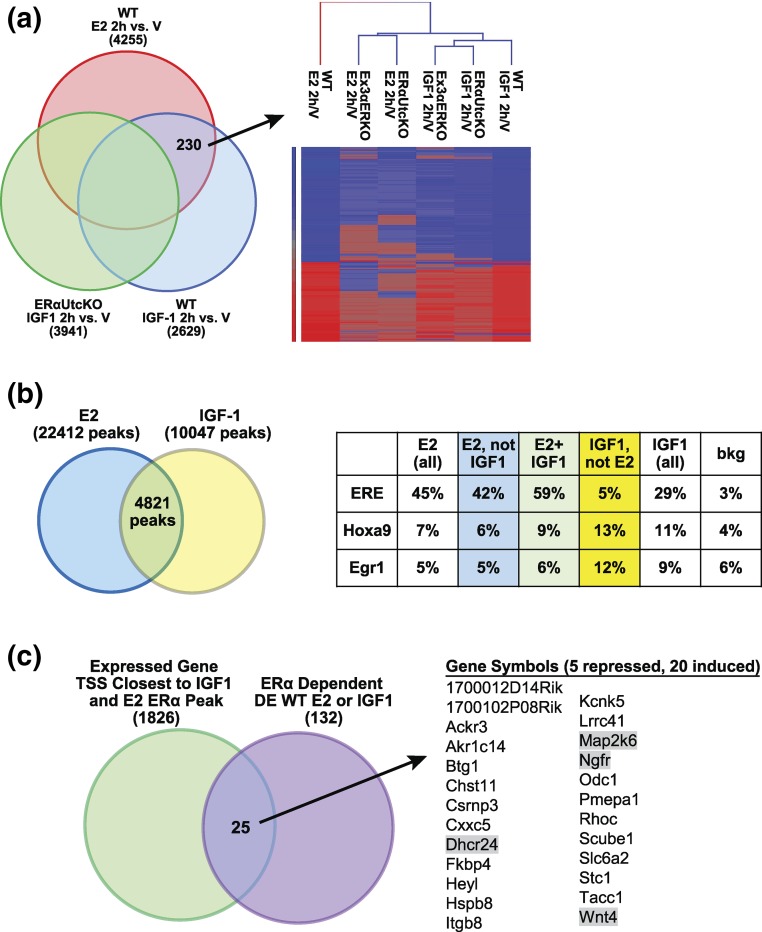

In the ERα-null context, IGF1 is unable to induce a uterine growth response to IGF1 (8, 13), despite the transcriptional responses that occur. We therefore evaluated our microarray data for possible ERα-dependent WT responses to better understand IGF1-induced transcriptional responses that might underlie the ERα-dependent WT growth response. Transcripts that might reflect IGF1 responses mediated by ERα were selected using Venn diagrams to choose 230 DE ERα-dependent array probes (98 probes for noncoding RNA, 132 probes for coding RNA). The goal was to focus on transcripts that are regulated by E2 or IGF1 in WT, but not regulated by IGF1 in ERαUtcKO uteri [Fig. 4(a)]. Enriched biological functions associated with these DE genes were identified using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis [Supplemental Fig. 3(b (3.3MB, pdf) )]. Activation of cell proliferation, suppression of cell death and activation of steroid synthesis were associated with these genes. Additionally, the regulation pattern of the 230 probes is consistent with activation of E2 and transforming growth factor-β1 signaling and with suppression of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 homeobox A and leukemia inhibitory factor responses.

Figure 4.

Selecting ERα-dependent transcriptional responses. (a) Left: Venn diagram showing selection of 230 ERα-dependent probes from overlap of transcripts DE by E2 and IGF1 in WT, but not by IGF1 in ERαUtcKO. Right: Hierarchical cluster of the 230 transcripts. (b) Venn diagram and table comparing E2- and IGF1-induced ERα binding sites and their enriched DNA motifs. (c) Venn diagram comparing the 1826 TSS closest to overlapping E2 and IGF1 ERα ChIP-peaks and the 132 coding RNA transcripts from the 230 transcripts selected in (a). The symbols of the 25 overlapping genes are listed. RT-PCR tested shaded genes.

To address whether ERα recruitment to chromatin was involved in ERα-dependent IGF1 transcriptional responses, we compared ERα ChIP-seq of uterine tissue from ovariectomized mice that were treated for 1 hour with V, E2, or IGF. Like E2, IGF1 increased ERα binding to uterine chromatin, although administering IGF1 resulted in fewer ERα binding peaks than administering E2 (Table 1). To assess whether E2 and IGF1 treatments recruited ERα to similar or different chromatin sites, we compared enriched DNA motifs in all overlapping and nonoverlapping E2 or IGF1 ERα peaks [Fig. 4(b)]. Of the 10,047 IGF1 ERα binding peaks, 4821 overlapped with the E2 ERα binding peaks. We found that 45% of all E2 peaks and 29% of all IGF1 peaks had enrichment of an estrogen response element (ERE) motif. The ERE motif was enriched in 59% of the E2 peaks overlapping with IGF1 peaks, indicating that both IGF1 and E2 facilitate ERα binding to its preferred ERE motif, potentially driving the ERα-dependent responses. The Homeobox a9 (Hoxa9) and early growth response 1 (Egr1) motifs were noticeably more enriched in the IGF1 peaks that did not overlap with E2 peaks.

Table 1.

ERα ChIP-seq

| Sample | ERα Peaks |

|---|---|

| V | 1548 |

| E2, 1 hour | 22,412 |

| IGF1, 1 hour | 10,047 |

| ICI, 1 hour | 24,994 |

Our analysis suggested that 230 E2- or IGF1-regulated probes are potentially mediated by a mechanism utilizing ERα directly [Fig. 4(a)], and our ERα ChIP-seq analysis suggested that IGF1 increases ERα chromatin binding (Table 1). Therefore, we compared expressed genes located nearest the ERα binding sites seen in both E2- and IGF1-treated ERα ChIP-seq samples to the 132 coding ERα-dependent E2- and IGF1-regulated transcripts from the microarray. We limited our analysis of microarray data to probes with coding annotations to facilitate comparison with annotated Refseq transcripts nearest ERα binding sites. Twenty-five genes with both E2 or IGF1 ERα binding within 50 kb and IGF1-induced transcriptional regulation were identified [Fig. 4(c)]. Four of these ERα-dependent transcripts [24-dehydrocholesterol reductase (Dhcr24), wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 4 (Wnt4), nerve growth factor receptor (Ngfr), and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6 (Map2k6)] were verified using RT-PCR. All four transcripts were regulated by both E2 and IGF1 in WT samples [Fig. 5(a)]; Ngfr and Map2k6 were not regulated by either E2 or IGF1 in ERα-null samples, indicating their ERα dependence. IGF1 induction of Dhcr24 and Wnt4 was observed in the Ex3αERKO. Examination of the ChIP-seq profiles near these transcripts indicated E2 and IGF1 both increased ERα recruitment [Supplemental Fig. 4(a) (3.3MB, pdf) , boxed areas] consistent with an ERα-dependent mechanism for an IGF1-induced response. In WT mice, the ERα antagonist ICI was effective in blocking induction of Dhcr24, Ngfr, and Wnt4 in response to either E2 or IGF1, also consistent with an ERα-dependent mechanism [Fig. 5(b)]. ICI inhibited E2 repression, but not IGF1 regulation of Map2k6 in WT. ChIP-seq data indicated that IGF1 increased ERα binding near these transcripts. We used ERα ChIP-PCR to verify ERα binding near Dhcr24, Ngfr and Wnt4. In fact, V uterine samples exhibited ERα binding to sites near the three induced transcripts that was increased by E2 or IGF1 treatment [Fig. 5(c)], consistent with a direct role for ERα in mediating some of the uterine transcriptional response to IGF1.

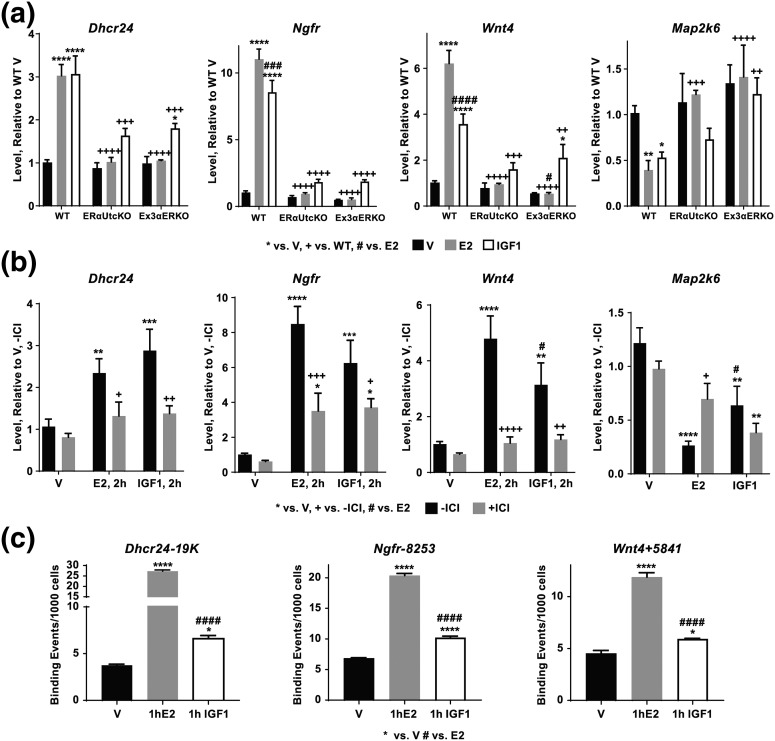

Figure 5.

Verification of ERα-dependent transcriptional responses. (a) RT-PCR showing E2 (2 hours) and IGF1 (2 hours) induction of Dhcr24, Wnt4, and Ngfr and repression of Map2k6 is ERα dependent. Two-way analysis of variance with posttest *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs V; ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001, ++++P <0.0001 vs WT; ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 E2 vs IGF1. N = 3 to 7 for all samples. Black = V, gray = E2, white = IGF1. (b) ICI inhibits E2 (2 hours) and IGF1 (2 hours) induction of Dhcr24, Wnt4 and Ngfr, consistent with a two-way analysis of variance with posttest *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs V; +P < 0.05, +++P < 0.001 vs –ICI; #P < 0.05 E2 vs IGF1. N = 4 to 5 for all samples. Black = no ICI, gray = with ICI. (c) ChIP-PCR confirms binding of ERα to sites near the Dhcr24, Ngfr, and Wnt4 transcripts. All three tested sites have basal ERα binding (V) that is increased by E2 or IGF1 activation. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 vs V; #### P < 0.0001 E2 vs IGF1. Black = V, gray = E2, white = IGF1. A pool of three uterine samples was tested per treatment; assay done in triplicate.

Discussion

Our study advances the understanding of the mechanisms that underlie IGF1-mediated uterine responses. IGF1 is one of the candidate paracrine growth factors induced by stromal ERα that leads to epithelial cell growth. The ability of E2 to increase epithelial cell proliferation in mice with uterine epithelial cell ERα deletion supports this paracrine mechanism (3). Our observations that ICI was unable to inhibit IGF1 responses in WT mice and of robust transcriptional response of the ERα-null mouse uterus to IGF1 seemed to indicate ERα-independent growth factor activity. To better test the impact of ERα specifically within the uterus, we added the study of the uterine specific ERα knockout mice. We used the second ERα-null model to address defects potentially arising from global ERα deletion; however, we did not find differences in the transcriptional responses of these two ERα-null models that informed the understanding of the role of ERα in the overall response. This indicates that the differences in IGF1 responses of the WT and ERα-null context are intrinsic to the uterine cells.

ERα-mediated responses to E2 include induction of IGF1, which then signals through its receptor-mediated pathway. We previously demonstrated E2-dependent recruitment of ERα to uterine chromatin, both at the IGF1 TSS (14) and at an enhancer approximately 50 KB 5′ of the IGF1 TSS (16). However, direct treatment with IGF1 leads to growth and transcriptional responses, and in the WT mouse, is not wholly dependent on ERα (Fig. 6). The transcripts highlighted in Fig. 3(a) use this ERα-independent mechanism. Because these transcripts were differentially expressed regardless of whether ERα was present, we hypothesized that IGF1 ERα binding would be less likely to occur nearby. Indeed, when we compared active genes nearest to overlapping E2 and IGF1 ERα ChIP-seq peaks to these ERα-independent differentially expressed genes, 223 of the 262 DE coding genes did not overlap with genes closest to ERα binding peaks [Supplemental Fig. 4(b (3.3MB, pdf) )]. Neither E2 nor IGF1 increased ERα binding near the Ppargc1a or Adamts5 genes [Supplemental Fig. 4(c (3.3MB, pdf) )], yet either agent repressed transcription. Hence, although the E2-mediated regulation of these transcripts required ERα, chromatin binding by other factors might be involved. E2 increases ERα binding at the Fos TSS and at 5′ and 3′ enhancers [Supplemental Fig. 4(c (3.3MB, pdf) )]. IGF1 also increases ERα binding at the Fos 3′ enhancer, and part of the 5′ enhancer [Supplemental Fig. 4(c (3.3MB, pdf) )]. However, IGF1 does not increase ERα binding at two of the smaller 5′ enhancers or at the main peak of ERα near the Fos TSS [highlighted by boxes in Supplemental Fig. 4(c (3.3MB, pdf) )]. These E2-induced ERα peaks were not within the overlapping E2 and IGF1 ERα peaks in Fig. 4(c). Some, but not all, of the ERα peaks near Fos are induced by either E2 or IGF1. The ability of E2 to induce ERα binding at more sites than IGF1 is likely why E2 is more robust than IGF1 in increasing Fos. Other genes, including the transcripts in Fig. 4(a), are regulated by direct IGF1-initiated activation of ERα. Consistent with an E2 ligand–independent ERα-dependent mechanism for these transcripts, several of the ERα-dependent genes exhibited E2 or IGF1-mediated ERα binding in the ChIP-seq datasets [Supplemental Fig. 4(a (3.3MB, pdf) )]. It is interesting to note that, based on the microarray data, 64% of the 654 ERα-independent IGF1-regulated transcripts were downregulated, whereas the proportion of 230 ERα-dependent transcripts that were downregulated was 44%, suggesting that the repression mechanism is less likely to involve direct ERα interaction.

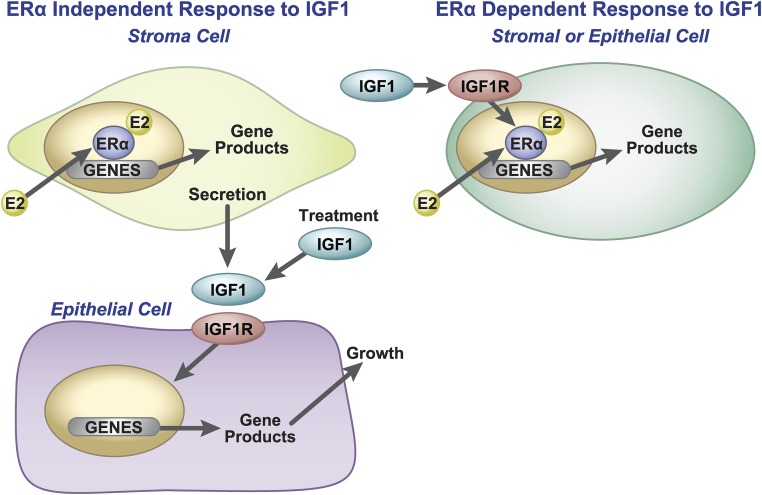

Figure 6.

Model: Role of ERα in adult uterine growth and IGF1 crosstalk. Left: ERα-independent response to IGF1. E2, through action of ERα in uterine stromal cells, induces IGF1, which then binds to IGF1 receptors on epithelial cells. The IGF1 receptor signaling leads to regulation of gene products. Direct treatment with IGF1 induces similar transcriptional responses, and does not require uterine ERα. Right: ERα-dependent/transcriptional cross talk in uterine cells. Both E2 and IGF1 can induce genes through the ERα. IGF1/IGF1R signals through ERα. E2 and IGF1 induce similar responses but require the ERα gene products are mostly upregulated.

ChIP-seq of uterine ERα showed that E2, IGF1 and ICI all increase ERα peaks (Table 1), indicating several details about the mechanisms of these different compounds. First, ERα-dependent IGF1-induced responses occur downstream of chromatin binding, and this may explain why ICI did not universally inhibit these responses, as IGF1 activates ERα through its AF-1 region, whereas ICI primarily impacts functions on the ligand binding/AF-2 region. Second, although ICI inhibits ERα activity both by decreasing ERα protein and preventing ERα-coactivator interactions, it is clearly also capable of inducing ERα chromatin binding. The Chip-seq samples were collected 1 hour after ICI treatment, at which time ERα is found in the nucleus, and before ERα degradation has occurred (17). Third, Hoxa9 and Egr1 motifs are significantly enriched in IGF1-induced ERα peaks relative to E2-induced peaks [Fig. 4(b)], suggesting these transcriptional modulators may impact ERα-dependent IGF1 response. EGR1 and several members of the homeobox family are detected in the mouse uterus and known to play essential roles in uterine function (18, 19). Homeobox motifs are enriched in general in the non-ERE containing ERα binding sites in the mouse uterus (16). Although a mouse uterine EGR1 cistrome has not been reported, data from mouse kidney indicated that EGR1 tended to interact with sites proximal to TSS (20), unlike ERα, which exhibits mostly distal interactions (16). Additionally, epidermal growth factor (EGF) activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling caused EGR1 binding to EGF target genes in prostate cells (21). Because EGF and IGF1 can both activate MAP kinases, it is possible that IGF1 can induce EGR1 binding to the IGF1-responsive transcripts in the mouse uterus. ERE motifs were prevalent in E2 and IGF1 overlapping ERα peaks [Fig. 4(b)] indicating that direct interactions drive much of the response.

Overall, our study indicates that direct treatment with IGF1 increased ERα recruitment to chromatin, driving regulation of ERα-dependent transcripts, consistent with crosstalk of signals from the IGF1 pathway to the ERα (Fig. 6). Additionally, IGF1 treatment can directly activate responses independent of ERα, consistent with the mechanism of paracrine uterine response and regulation. These observations impact our understanding of E2 and IGF1 signal responses in a whole animal model. Such knowledge has potential applications to reproductive health of humans, livestock, and wildlife.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIEHS Microarray Group for microarray data, NIEHS Histology Core for tissue embedding and sectioning, and the NIEHS Comparative Medicine Branch for surgery and animal care.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health NIEHS Grant 1ZIAES070065 to K.S.K.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Appendix.

Antibody Table

| Peptide/Protein Target | Antigen Sequence (if Known) | Name of Antibody | Manufacturer, Catalog No., and/or Name of Individual Providing the Antibody | Species Raised in; Monoclonal or Polyclonal | Dilution Used | RRID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR1 | ER-1D5 | Biocare Medical, ACA 054C | Mouse; monoclonal | 1:200 | AB_2651037 | |

| Ki67 | Purified mouse anti-Ki-67 | BD Pharminogen, 550609 | Mouse; monoclonal | 1:100 | AB_393778 |

Footnotes

- Adamts5

- a disintegrin-like and metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 5

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- ChIP-seq

- chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing

- DE

- differentially expressed

- Dhcr24

- 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase

- E2

- estrogen

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- Egr1

- early growth response 1

- ERα

- estrogen receptor α

- ERE

- estrogen response element

- Fos

- FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene

- GEO

- Gene Expression Omnibus

- IGF1

- insulinlike growth factor 1

- IGF1R

- insulinlike growth factor 1 receptor

- Map2k6

- mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6

- Ngfr

- nerve growth factor receptor

- NIEHS

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- PGR

- progesterone receptor

- Ppargc1α

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α

- RRID

- research resource identifier

- RT-PCR

- real-time polymerase chain reaction

- TSS

- transcription start site

- WT

- wild-type.

References

- 1.Cooke PS, Buchanan DL, Young P, Setiawan T, Brody J, Korach KS, Taylor J, Lubahn DB, Cunha GR. Stromal estrogen receptors mediate mitogenic effects of estradiol on uterine epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(12):6535–6540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy LJ, Ghahary A. Uterine insulin-like growth factor-1: regulation of expression and its role in estrogen-induced uterine proliferation. Endocr Rev. 1990;11(3):443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winuthayanon W, Hewitt SC, Orvis GD, Behringer RR, Korach KS. Uterine epithelial estrogen receptor α is dispensable for proliferation but essential for complete biological and biochemical responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(45):19272–19277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu L, Pollard JW. Estradiol-17beta regulates mouse uterine epithelial cell proliferation through insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(40):15847–15851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards RG, DiAugustine RP, Petrusz P, Clark GC, Sebastian J. Estradiol stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and insulin receptor substrate-1 in the uterus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(21):12002–12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adesanya OO, Zhou J, Samathanam C, Powell-Braxton L, Bondy CA. Insulin-like growth factor 1 is required for G2 progression in the estradiol-induced mitotic cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(6):3287–3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klotz DM, Hewitt SC, Ciana P, Raviscioni M, Lindzey JK, Foley J, Maggi A, DiAugustine RP, Korach KS. Requirement of estrogen receptor-alpha in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-induced uterine responses and in vivo evidence for IGF-1/estrogen receptor cross-talk. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(10):8531–8537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewitt SC, Kissling GE, Fieselman KE, Jayes FL, Gerrish KE, Korach KS. Biological and biochemical consequences of global deletion of exon 3 from the ER- alpha gene. FASEB J. 2010;24(12):4660–4667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Research Council Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewitt SC, Li L, Grimm SA, Winuthayanon W, Hamilton KJ, Pockette B, Rubel CA, Pedersen LC, Fargo D, Lanz RB, DeMayo FJ, Schütz G, Korach KS. Novel DNA motif binding activity observed in vivo with an estrogen receptor α mutant mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28(6):899–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10(3):R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38(4):576–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewitt SC, Collins J, Grissom S, Deroo B, Korach KS. Global uterine genomics in vivo: microarray evaluation of the estrogen receptor alpha-growth factor cross-talk mechanism. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(3):657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hewitt SC, Li Y, Li L, Korach KS. Estrogen-mediated regulation of Igf1 transcription and uterine growth involves direct binding of estrogen receptor alpha to estrogen-responsive elements. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(4):2676–2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards RG, Walker MP, Sebastian J, DiAugustine RP. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor-insulin receptor substrate complexes in the uterus. Altered signaling response to estradiol in the IGF-1(m/m) mouse. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(19):11962–11969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hewitt SC, Li L, Grimm SA, Chen Y, Liu L, Li Y, Bushel PR, Fargo D, Korach KS. Research resource: whole-genome estrogen receptor alpha binding in mouse uterine tissue revealed by ChIP-seq. Mol. Endocrinol . 2012;26(5):887–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson MK, Nemmers LA, Beckman WC Jr, Davis VL, Curtis SW, Korach KS. The mechanism of ICI 164,384 antiestrogenicity involves rapid loss of estrogen receptor in uterine tissue. Endocrinology. 1991;129(4):2000–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du H, Taylor HS. The role of hox genes in female reproductive tract development, adult function, and fertility. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;6(1):a023002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo B, Tian XC, Li DD, Yang ZQ, Cao H, Zhang QL, Liu JX, Yue ZP. Expression, regulation and function of Egr1 during implantation and decidualization in mice. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(16):2626–2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portale AA, Zhang MY, David V, Martin A, Jiao Y, Gu W, Perwad F. Characterization of FGF23-Dependent Egr-1 Cistrome in the Mouse Renal Proximal Tubule. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arora S, Wang Y, Jia Z, Vardar-Sengul S, Munawar A, Doctor KS, Birrer M, McClelland M, Adamson E, Mercola D. Egr1 regulates the coordinated expression of numerous EGF receptor target genes as identified by ChIP-on-chip. Genome Biol. 2008;9(11):R166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]