It is impossible to consider, even in the briefest summary, the future program of the public health movement without at least some reference to the vast and fertile fields of mental hygiene . . . in the not-distant future I am inclined to believe that the care of mental health will occupy a share of our energies perhaps as large as that devoted to the whole range of other disorders affecting other organs of the body.

—Charles-Edward Amory Winslow, President, American Public Health Association, 19261(p1078)

For nearly 100 years, public health officials have called for the integration of mental health into mainstream public health practice, and rightfully so. Mental health conditions increase the risk of injuries, physical health problems, and premature death and can have a negative impact on quality of life.2 As with physical health, patterns in population mental health are produced through a complex interplay of biological and social factors and can be improved by policy interventions that reduce exposure to stressors and cultivate resources that promote resilience.3 In many low-income communities, segregation, community disinvestment, and structural inequalities create conditions that make violence a ubiquitous stressor that increases the risk of myriad mental health problems—especially trauma, anxiety, and depressive disorders.4 Yimgang et al.’s study (p. 1455) of the impact of the 2015 Baltimore, Maryland, riots on depressive symptoms among low-income mothers highlights this relationship and reinforces Winslow’s call for public health practitioners to address violence and mental health.

Yimgang et al. used data collected through Baltimore Children’s HealthWatch, a cross-sectional study that continuously collects data from low-income mothers in health care settings. The study assessed differences in the prevalence of depressive symptoms between mothers who were surveyed before, during, and after the Baltimore riots. To estimate the effect of riot exposure on depressive symptoms, the study compared prevalence rates for mothers living in zip codes where the riots occurred (i.e., proximal neighborhoods) with prevalence rates for mothers who did not live in these zip codes (i.e., distal neighborhoods). Trend analyses found that prevalence of depressive symptoms increased significantly among mothers in proximal neighborhoods, peaking at 50% during the riots in August 2015, whereas prevalence did not increase among mothers in distal neighborhoods. Given the importance of maternal mental health to child development, Yimgang et al. note that “there is an urgent need for public health practitioners to develop policies and programs to ensure that mothers and children are protected from community violence and civil unrest” (p. 1461)—a call to action with which Winslow would agree.

POTENTIAL ROLE OF LOCAL HEALTH DEPARTMENTS

With their focus on populations and prevention, local health departments (LHDs) have potential to address mental health and violence in ways that complement the activities of other local agencies. Although local behavioral health agencies exist in many jurisdictions and have a mandate to address mental health issues, they are typically limited to providing clinical services to individual people with serious mental illness. Likewise, although local law enforcement agencies have a mandate to pursue justice and restore order after individual incidents of violence occur, they generally do not engage in activities to prevent violence or address its mental health sequelae. LHDs can complement the work of these agencies through population-based mental health activities such as surveillance, assessment, planning, training, stigma reduction campaigns, and policy advocacy.2,3,5,6 Resources such as The Community Guide—Public Health Accreditation Board Standards Crosswalk and National Academy of Medicine reports such as Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People and Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity provide guidance about actions LHDs can take to address mental health and violence in the communities they serve.

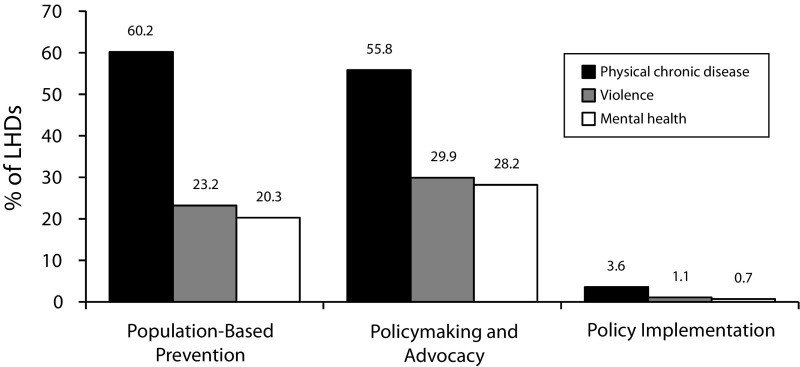

There is a strong rationale for LHDs to address mental health and violence, but do LHDs perform population-based activities to address these issues? Some LHDs (e.g., Baltimore; New York City; San Francisco, CA) have launched initiatives that target mental health and violence, but national data have suggested that such activities are the exception, not the norm. The 2016 Profile Study, a national survey of LHDs, indicated that the proportion of LHDs engaged in population-based activities to address violence and mental health is about half that of LHDs engaged in such activities to address physical chronic disease (Figure 1). These data are consistent with an analysis of 2013 Profile Study data that found that 44.2% of LHDs in the United States performed none of eight mental health activities that were assessed.5

FIGURE 1—

Proportion of Local Health Departments in the United States Engaged in Population-Based Activities to Address Physical Chronic Disease, Violence, and Mental Health

Note. LHD = local health department. Population-based prevention activities are focused on “mental illness” for mental health and include those performed directly and contracted out by local health departments. Policymaking and advocacy activities include “injury prevention” for violence and “obesity” for chronic disease. Policy implementation activities include “obesity” for chronic disease.

Source. 2016 Profile Study of Local Health Departments, National Association of County & City Health Officials.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Why is it that more LHDs are not engaged in activities to address violence and promote population mental health? Is it that LHD officials do not perceive violence and mental health as public health concerns, or is it that barriers impede LHDs from addressing these issues? In a recent qualitative study, my colleagues and I asked LHD officials.6

Interview respondents adamantly expressed that they saw mental health as integral to population health and identified violence as a root cause of mental health problems. They also described how communities called on LHDs to address mental health issues and prevent violence. Many respondents explained that these issues surfaced as top priorities in community health needs assessments that were conducted as part of the Public Health Accreditation Board process. It is plausible that LHD involvement in mental health promotion and violence prevention will increase as the trend toward LHD accreditation continues, especially given a recent policy change stating that the board will accept documentation of population-based mental health promotion and violence prevention activities when making accreditation decisions (goo.gl/iAoZNv).

Despite the desire to address mental health and violence, LHD officials explained that they lacked knowledge about actions their LHDs could take to address these issues. Many respondents described how mental health was not covered in their public health training. A content analysis of accredited school of public health curricula, for example, found that only 14.6% offered concentrations in mental health.7 Respondents also identified inadequate surveillance data as a barrier to performing mental health activities. The Core Section of the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an important data source for many LHDs, includes only one question about current mental health status (Module 2) and one question about lifetime history of depression (Module 6)—whereas it includes dozens of questions about physical health. Greater integration of mental health and violence content into public health education and inclusion of mental health variables in population-based surveys are priorities for action.

Many LHD officials also described challenges related to relationships with local behavioral health agencies. Some respondents stated that LHDs were reluctant to address mental health because they were afraid of infringing on the turf of another agency. Respondents also described how financing arrangements hindered collaboration, and sometimes fostered contentious relationships, between LHDs and local behavioral health agencies. New models of health care financing, such as Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Programs and the Accountable Health Communities model, have potential to spur collaboration between LHDs and local behavioral health agencies and advance population-based approaches to mental health and violence.3

CONCLUSIONS

Exposures to riots, such as the focus of the study by Yimgang et al., are relatively uncommon. Chronic exposure to community violence, however, is not. Community violence is a cause of mental health problems, but it is also a consequence of the same structural inequalities (e.g., inequitable education funding, food and housing insecurity, discrimination) that generate stressors that also the increase risk of poor mental health. A problem of such complexity is unlikely to be meaningfully addressed through individual-level interventions. Promoting mental health and preventing violence requires population-based approaches, which LHDs are potentially well positioned to lead. Much progress remains, however, to advance the role of LHDs in mental health promotion and violence prevention and transform Winslow’s1 vision into a reality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R21MH111806; R25MH08091).

I thank Rosie Mae Henson, MPH, for her thoughtful feedback on this article and

Note. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

See also Yimgang et al., p. 1455.

REFERENCES

- 1.Winslow C-E. Public health at the crossroads. Am J Public Health. 1926;16(11):1075–1085. doi: 10.2105/ajph.16.11.1075-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen N, Galea S., editors. Population Mental Health: Evidence, Policy, and Public Health Practice. New York: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krueger J, Counts N, Riley B. Promoting mental health and well-being in public health law and practice. J Law Med Ethics. 2017;45(1, suppl):37–40. doi: 10.1177/1073110517703317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Baltes BB. Community violence: a meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21(1):227–259. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purtle J, Klassen AC, Kolker J, Buehler JW. Prevalence and correlates of local health department activities to address mental health in the United States. Prev Med. 2016;82:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purtle J, Peters R, Kolker J, Klassen AC. Factors perceived as influencing local health department involvement in mental health. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1):64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker ER, Kwon J, Lang DL, Levinson RM, Druss BG. Mental health training in schools of public health: history, current status, and future opportunities. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(1):208–217. doi: 10.1177/003335491613100130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]