Abstract

Objective:

Although alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are prevalent among older individuals, few studies have examined the course and predictors of AUDs from their onset into the person’s 50s. This study describes the AUD course from ages 50 to 55 in participants who developed AUDs according to criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), during the San Diego Prospective Study (SDPS).

Method:

Among the 397 university students in the SDPS who were followed about every 5 years from age 20 (before AUD onset), 165 developed AUDs, 156 of whom were interviewed at age 55. Age 50–55 outcomes were compared regarding age 20–50 characteristics. Variables that differed significantly across outcome groups were evaluated using binary logistic regression analyses predicting each outcome type.

Results:

Between ages 50 and 55, 16% had low-risk drinking, 36% had high-risk drinking, 38% met DSM-5 AUD criteria, and 10% were abstinent. Baseline predictors of outcome at ages 50–55 included earlier low levels of response to alcohol predicting DSM-5 AUDs and abstinence, higher drinking frequency predicting DSM-5 diagnoses and lower predicting low-risk drinking, higher participation in treatment and/or self-help groups predicting abstinence and lower predicting DSM-5 AUDs, later ages of AUD onset predicting high-risk drinking, and cannabis use disorders predicting abstinent outcomes.

Conclusions:

Despite the high functioning of these men, few were abstinent or maintained low-risk drinking during the recent 5 years, and 38% met DSM-5 AUD criteria. The data may be helpful to both clinicians and researchers predicting the future course ofAUDs in their older patients and research participants.

Heavy drinking and alcohol problems are highly prevalent, chronic, and serious conditions that usually begin in the teens and persist over time, with 25% of individuals in their 50s drinking daily and/or ever consuming five or more drinks per occasion (Breslow et al., 2003; Grant et al., 2015, Gunzerath et al., 2004; Molander et al., 2010; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2010; Rehm et al., 2011). Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) can decrease life spans by a decade (Lundin et al., 2015; McCaul et al., 2010), and two thirds of alcohol-related deaths occur between ages 45 and 60 (Rehm et al., 2011).

AUDs typically follow a course of exacerbations and remissions with complex interrelationships among risk factors that are best studied by identifying individuals before the condition develops and evaluating them repeatedly over decades. This can be challenging because research funding is usually short term, and longer follow-ups are expensive.

Most longitudinal studies are 1–5 years (Dawson et al., 2012; Maisto et al., 2007) and some cover 10–15 years (Brennan et al., 2010; Mann et al., 2005; Moos & Moos, 2006; Schutte et al., 2006), but prospective studies that began at age 20 and continued into the sixth decade of life are rare (e.g., Jacob et al., 2009; Penick et al., 2010; Upah et al., 2015; Vaillant, 2003).

For decades, our group has focused on predictors of AUDs and related outcomes that included demography; earlier substance use onsets, frequencies, quantities, and problems; prior treatment experiences; and genetically influenced characteristics (e.g., Schuckit & Smith, 1996, 2011; Schuckit et al., 2004, 2014). Although limitations in the time subjects were willing to spend during baseline evaluations for these studies and the specific interests of our research group limited the baseline items that could be gathered in our prospective work, the data available from our earlier evaluations and our repeated contact with our subjects between ages 20 and 55 can offer useful information about a disorder like AUDs that fluctuates between exacerbations and remissions. The latter has been defined different ways across the literature (e.g., Gastfriend et al., 2007), including total alcohol abstinence, absence of AUD criterion items according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; American Psychiatric Association, 1980, 1987, 1994, 2013), and low-versus high-risk drinking as set forth by the NIAAA (Breslow et al., 2003).

Prior studies indicate that remissions are likely to increase with age, European American background, having been married, and, for nonabstinent outcomes, previous lower alcohol quantities, frequencies, and alcohol problems (Bischof et al., 2001; Dawson et al., 2012; Moos & Moos, 2006; Schuckit et al., 1997; Schutte et al., 2006). Abstinent outcomes are more likely in individuals with greater alcohol problems and those with experience with formal treatment or self-help groups (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous), programs that usually emphasize nondrinking outcomes (Dawson et al., 2012; Helzer et al., 1985; Schutte et al., 2006; Timko et al., 2000; Vaillant, 2003). Remission also relates in complex ways to a person’s socioeconomic status and social support systems (Moos et al., 2010; Prescott & Kendler, 2001). However, with some important exceptions (e.g., Vaillant, 2003), most longitudinal studies of the course of AUDs were generated from treatment samples that are often of lower socioeconomic status, and less is known about the clinical course of individuals with AUDs from higher functioning groups.

Several genetically related characteristics also relate to the course of drinking and AUDs, including an endophenotype of special interest to our group. A low level of response to alcohol (low LR) increases the AUD risk and might also predict higher remission rates among individuals with AUDs (Schuckit & Smith, 1996, 2011; Trim et al., 2013). The low LR is not closely linked to externalizing or internalizing characteristics, and, thus, is not related to dependence on illicit drugs or psychiatric disorders other than alcohol-induced conditions (Schuckit et al., 2004).

This study extracted data from the San Diego Prospective Study (SDPS) in which male probands entered the protocol at about age 20 as drinking, non–alcohol-dependent college students and nonacademic staff, with more than 90% of these subjects followed at age 30 and every 5 years there-after. Half of the men had an alcohol-dependent father, and half reported no close relative with an AUD, with the two groups selected to be similar on demography and substance use histories. The selection of a sample, half of whom had an alcohol-dependent relative, resulted in a high proportion who developed an AUD. Thus, the results presented here are relatively unique among long-term studies of individuals with AUDs.

Our current interest is in whether clinicians or researchers who had followed the men with AUDs from ages 20 to 50 could predict their alcohol-related outcomes. Four hypotheses guided the analyses. In Hypothesis 1, reflecting the past high education and life achievement for SDPS probands, we predicted that in their sixth decade many of these men would have developed abstinence (Group 4 in our analyses) or low-risk drinking in the absence of multiple alcohol-related problems (Group 1). As a corollary, few participants will meet the criteria for AUDs (Group 3) between ages 50 and 55. Based on the existing literature, Hypothesis 2 predicted that low-risk drinking would be most likely for men with higher LRs to alcohol, and lower past drinking quantities, frequencies, and problems (e.g., Dawson et al., 2012; Moos & Moos, 2006; Schuckit et al., 1997; Trim et al., 2013). Hypothesis 3 predicted that the more problematic outcome of high-risk drinking ages 50–55 would relate to LRs, alcohol intake patterns, and alcohol problems between the low-risk drinkers and probands who maintained abstinence during the most recent follow-up. Hypothesis 4 predicted that the probands who maintained abstinence at ages 50–55 would have the lowest LR and highest drinking quantities and report the highest rates of exposure to formal treatment and/or self-help group participation (Dawson et al., 2012; Helzer et al., 1985; Schutte et al., 2006; Vaillant, 2003).

Method

Participants and baseline evaluations

Following approval from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), Human Subject’s Protections Committee, the SDPS began in 1978 with 18- to 25-year-old male European American and White Hispanic students and nonacademic staff selected among respondents to a randomly mailed questionnaire (Schuckit & Gold, 1988; Schuckit & Smith, 1996). Participants had to have consumed alcohol the prior year but not ever fit criteria for alcohol dependence in DSM-III or DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1980, 1987), with individuals excluded for histories of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or physical problems that precluded alcohol challenges. Recruitment began with a participant who reported a father with alcohol dependence, with sub-sequent selection of a family-history–negative comparison individual with similar demography, substance use history, and past-year drinking pattern.

Potential participants were evaluated using in-person interviews based on a precursor of the follow-up instrument described below (Robins et al., 1981; Schuckit & Smith, 1996, 2011; Schuckit et al., 2014). Laboratory-based challenges with 0.75 ml/kg of absolute alcohol established their intensity of response to alcohol using the Subjective High Assessment Scale (SHAS), changes in body sway, and changes in hormones and electrophysiological measures, depending on the specific protocol (Schuckit & Gold, 1988; Schuckit & Smith, 1996, 2011). Data from different measures and across years were combined using z scores into one overall alcohol-challenge LR value in which lower scores reflected lower LRs per drink.

Follow-up evaluations

Assessments began in 1988 (average age 30) and then were conducted every 5 years using a modification of the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism interview, with validities and reliabilities greater than .75 for most psychiatric diagnoses (Hesselbrock et al., 1999). Age 30, 35, and 40 evaluations were face-to-face, with a parallel interview about the proband performed with a spouse or close friend. Reflecting financial restrictions, age 50 and 55 follow-ups were limited to phone interviews of probands.

At age 35, probands completed the then recently developed Self-Report of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) retrospective questionnaire regarding the average drinks required for up to four effects actually experienced (feeling first effect, slurring speech, unsteady gait, or unwanted falling asleep) during three life epochs: the first five times drinking (SRE-5), most recent 3 months, and their heaviest drinking period. Total scores (SRE-T) reflected average drinks for effects across all three epochs, as the sum of the number drinks required for up to four effects divided by the number of the effects reported, and SRE-5 scores reflected the average drinks required during the first 5 times of drinking only (Ray et al., 2007; Schuckit & Smith, 1996, 2011). Higher SRE scores indicate more drinks needed for effects, or lower LRs per drink. The SRE Cronbach’s a is greater than .90, with retest reliabilities greater than .80. Age 35 follow-ups also evaluated novelty seeking (Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire; Cloninger et al., 1996), sensation seeking (Zuckerman Questionnaire; Zuckerman & Kuhlman, 2000), and impulsivity (Karolinska Personality Questionnaire; Schalling & Asberg, 1985).

By age 50, 11 of the original 453 probands had died, leaving 442 eligible for follow-up (Schuckit & Smith, 1996, 2011; Schuckit et al., 2014). Among these, 397 (90%) participated in all follow-ups from ages 30 through 50 (Schuckit et al., 2014), 165 of whom (41.6%) had developed a DSM-IV AUD (61.5% with dependence and 38.5% with abuse) at any assessment (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). With the emphasis on predictors of the course of AUDs and their prevalence during the sixth life decade, these men with prior AUDs were the focus of the current analyses.

Analyses

Like the approach used in a recent study (McCutcheon et al., 2017), four age 50–55 outcome groups were established for those with DSM-IV AUD criteria before age 50. Group 1 drank during the most recent follow-up, reporting quantities within the NIAAA guidelines for low-risk drinking (<4 standard drinks per occasion and <14 drinks per week) and denied having more than 1 of the 11 DSM-5 AUD diagnostic problems (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Group 2 (high-risk drinking) exceeded those quantities ages 50–55 and denied more than 1 DSM-5 AUD items. Subjects with 2 or more DSM-5 alcohol-related problems were categorized as fulfilling criteria for a DSM-5 AUD ages 50–55 (Group 3), and the abstinent outcome category indicated men who denied drinking during the most recent 5-year follow-up.

Comparisons across the four outcome groups were first evaluated using chi-square for categorical data and analysis of variance for continuous variables. We next evaluated which variables from the age 30–50 follow-ups significantly differentiated across the four age 50–55 outcome groups when considered along with other significant variables. There are three types of data used in the relevant analyses in Table 3: (a) single assessment items (e.g., SRE and age at onset); (b) drinking variables in which the number represents the maximum value reported across age 30–50 interviews (e.g., maximum drinks), or a simple count of occurrences (e.g., the total number of the 11 DSM-IV AUD criteria met across age 30–50 interviews); and (c) dichotomous variables (e.g., yes or no to cannabis use) indicating that a subject fulfilled that item at any age 30–50 interview. For the regression analyses in Table 4, we considered a simultaneous-entry multinomial logistic regression analysis but rejected this approach because of our modest sample size and our desire to identify variables that predicted each outcome rather than evaluating predictors of only three groups with the fourth used as a reference group. Therefore, this final analytic step used four binary logistic regression analyses predicting each outcome independently. Missing data were handled through a maximum likelihood procedure (Collins et al., 2001).

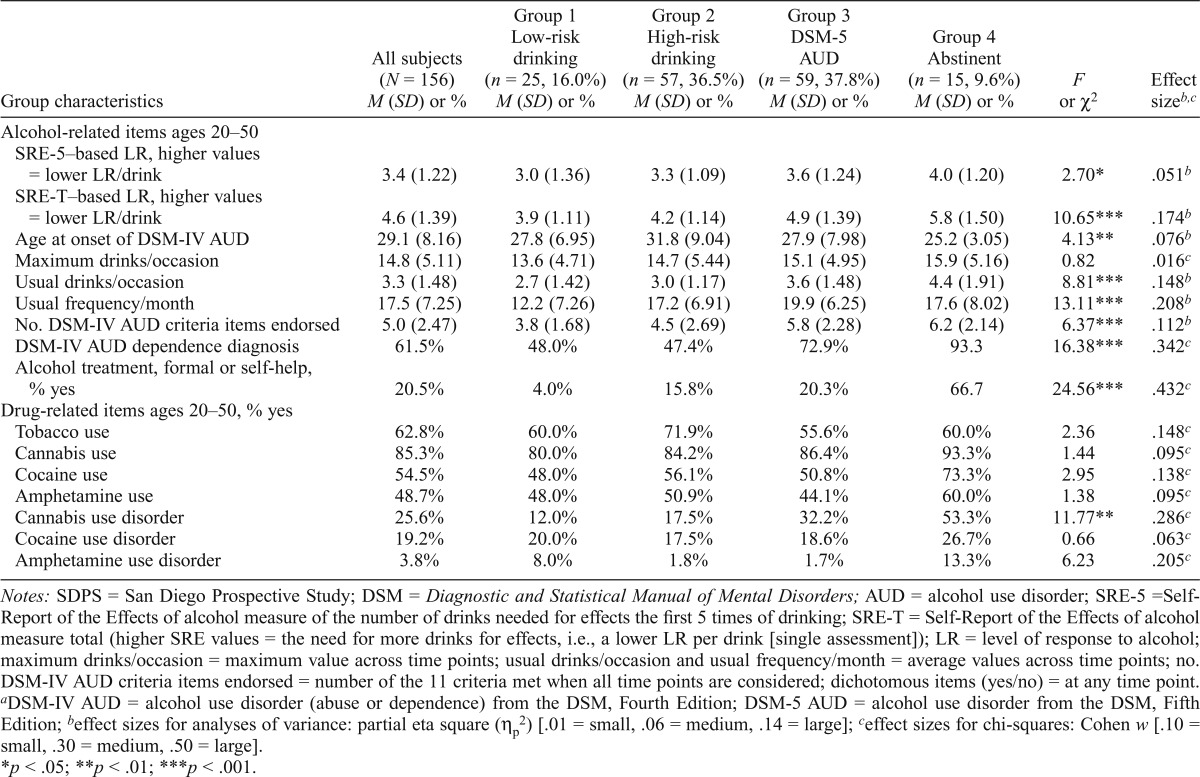

Table 3.

Alcohol and drug histories across follow-ups at ages 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 for the 156 SDPS men who had developed DSM-IV AUDsa

| Group characteristics | All subjects (N = 156) M (SD) or % | Group 1 Low-risk drinking (n = 25, 16.0%) M (SD) or % | Group 2 High-risk drinking (n = 57, 36.5%) M (SD) or % | Group 3 DSM-5 AUD (n = 59, 37.8%) M (SD) or % | Group 4 Abstinent (n =15, 9.6%) M (SD) or % | F or χ2 | Effect sizeb,c |

| Alcohol-related items ages 20–50 SRE-5–based LR, higher values = lower LR/drink | 3.4(1.22) | 3.0 (1.36) | 3.3 (1.09) | 3.6 (1.24) | 4.0 (1.20) | 2.70* | .051* |

| SRE-T–based LR, higher values = lower LR/drink | 4.6 (1.39) | 3.9 (1.11) | 4.2 (1.14) | 4.9 (1.39) | 5.8 (1.50) | 10.65*** | .174b |

| Age at onset of DSM-IV AUD | 29.1 (8.16) | 27.8 (6.95) | 31.8 (9.04) | 27.9 (7.98) | 25.2 (3.05) | 4.13** | .076b |

| Maximum drinks/occasion | 14.8 (5.11) | 13.6 (4.71) | 14.7 (5.44) | 15.1 (4.95) | 15.9 (5.16) | 0.82 | .016c |

| Usual drinks/occasion | 3.3 (1.48) | 2.7 (1.42) | 3.0 (1.17) | 3.6 (1.48) | 4.4 (1.91) | 8.81*** | .148b |

| Usual frequency/month | 17.5 (7.25) | 12.2 (7.26) | 17.2(6.91) | 19.9 (6.25) | 17.6 (8.02) | 13.11*** | .208b |

| No. DSM-IV AUD criteria items endorsed | 5.0 (2.47) | 3.8 (1.68) | 4.5 (2.69) | 5.8 (2.28) | 6.2 (2.14) | 6.37*** | .112b |

| DSM-IV AUD dependence diagnosis | 61.5% | 48.0% | 47.4% | 72.9% | 93.3 | 16.38*** | .342c |

| Alcohol treatment, formal or self-help, | |||||||

| % yes | 20.5% | 4.0% | 15.8% | 20.3% | 66.7 | 24.56*** | .432c |

| Drug-related items ages 20–50, % yes Tobacco use | 62.8% | 60.0% | 71.9% | 55.6% | 60.0% | 2.36 | .148c |

| Cannabis use | 85.3% | 80.0% | 84.2% | 86.4% | 93.3% | 1.44 | .095c |

| Cocaine use | 54.5% | 48.0% | 56.1% | 50.8% | 73.3% | 2.95 | .138c |

| Amphetamine use | 48.7% | 48.0% | 50.9% | 44.1% | 60.0% | 1.38 | .095c |

| Cannabis use disorder | 25.6% | 12.0% | 17.5% | 32.2% | 53.3% | 11.77** | .286c |

| Cocaine use disorder | 19.2% | 20.0% | 17.5% | 18.6% | 26.7% | 0.66 | .063c |

| Amphetamine use disorder | 3.8% | 8.0% | 1.8% | 1.7% | 13.3% | 6.23 | .205c |

Notes: SDPS = San Diego Prospective Study; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; AUD = alcohol use disorder; SRE-5 =Self-Report of the Effects of alcohol measure of the number of drinks needed for effects the first 5 times of drinking; SRE-T = Self-Report of the Effects of alcohol measure total (higher SRE values = the need for more drinks for effects, i.e., a lower LR per drink [single assessment]); LR = level of response to alcohol; maximum drinks/occasion = maximum value across time points; usual drinks/occasion and usual frequency/month = average values across time points; no. DSM-IV AUD criteria items endorsed = number of the 11 criteria met when all time points are considered; dichotomous items (yes/no) = at any time point.

DSM-IV AUD = alcohol use disorder (abuse or dependence) from the DSM, Fourth Edition; DSM-5 AUD = alcohol use disorder from the DSM, Fifth Edition;

effect sizes for analyses of variance: partial eta square (ηp2) [.01 = small, .06 = medium, .14 = large];

effect sizes for chi-squares: Cohen w [.10 = small, .30 = medium, .50 = large].

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

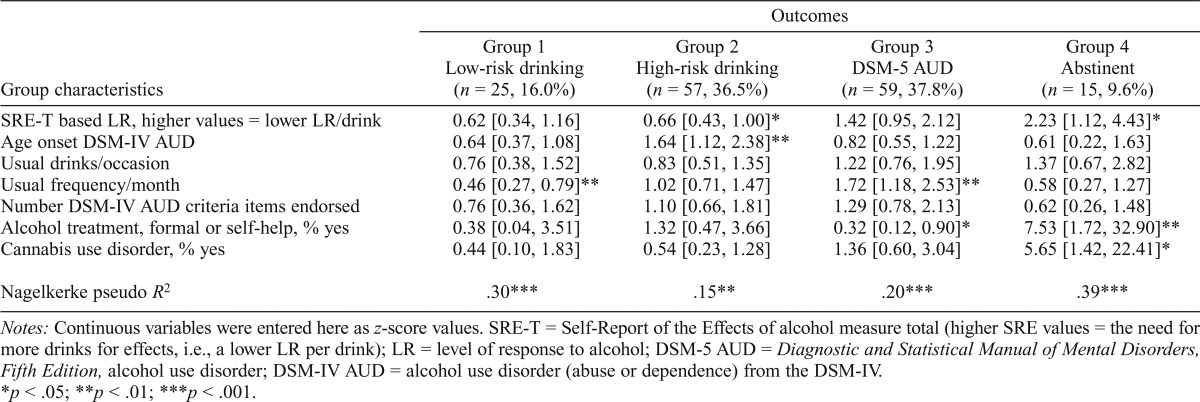

Table 4.

Binary logistic regression analyses using relevant age 20–50 variables from Table 3 to predict each of the four outcomes ages 50–55; odds ratios [95% confidence interval]

| Outcomes |

||||

| Group characteristics | Group 1 Low-risk drinking (n = 25, 16.0%) | Group 2 High-risk drinking (n = 57, 36.5%) | Group 3 DSM-5 AUD (n = 59, 37.8%) | Group 4 Abstinent (n = 15,9.6%) |

| SRE-T based LR, higher values = lower LR/drink | 0.62 [0.34, 1.16] | 0.66 [0.43, 1.00]* | 1.42 [0.95, 2.12] | 2.23 [1.12, 4.43]* |

| Age onset DSM-IVAUD | 0.64 [0.37, 1.08] | 1.64 [1.12, 2.38]** | 0.82 [0.55, 1.22] | 0.61 [0.22, 1.63] |

| Usual drinks/occasion | 0.76 [0.38, 1.52] | 0.83 [0.51, 1.35] | 1.22 [0.76, 1.95] | 1.37 [0.67, 2.82] |

| Usual frequency/month | 0.46 [0.27, 0.79]** | 1.02 [0.71, 1.47] | 1.72 [1.18, 2.53]** | 0.58 [0.27, 1.27] |

| Number DSM-IV AUD criteria items endorsed | 0.76 [0.36, 1.62] | 1.10 [0.66, 1.81] | 1.29 [0.78, 2.13] | 0.62 [0.26, 1.48] |

| Alcohol treatment, formal or self-help, % yes | 0.38 [0.04, 3.51] | 1.32 [0.47, 3.66] | 0.32 [0.12, 0.90]* | 7.53 [1.72, 32.90]** |

| Cannabis use disorder, % yes | 0.44 [0.10, 1.83] | 0.54 [0.23, 1.28] | 1.36 [0.60, 3.04] | 5.65 [1.42, 22.41]* |

| Nagelkerke pseudo R2 | .30*** | .15** | .20*** | .39*** |

Notes: Continuous variables were entered here as z-score values. SRE-T = Self-Report of the Effects of alcohol measure total (higher SRE values = the need for more drinks for effects, i.e., a lower LR per drink); LR = level of response to alcohol; DSM-5 AUD = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, alcohol use disorder; DSM-IV AUD = alcohol use disorder (abuse or dependence) from the DSM-IV

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Results

Table 1 presents baseline (about age 20) and several early-course characteristics for the four age 50–55 outcome groups of probands who developed DSM-IV AUDs between ages 20 and 50 (N = 156; 94.5% of the 165 men who had developed an AUD). Reflecting baseline selection criteria, almost all had European American ethnicities, and they had completed 15 years of education before entering the protocol. At study entry, 80% identified with a religion (34.8% Protestant, 32.7% Catholic, and 12.5% other), and 13.5% were married. As shown in the last columns, there were no significant differences for these demographic characteristics across the groups. Also, no significant differences were seen regarding their baseline alcohol-related characteristics, illicit drug patterns, or their internalizing- and externalizing-related variables. The z-scored baseline alcohol challenge SHAS scores demonstrated a pattern of highest LRs for men in Group 1 and lowest in Group 4, but these were not significantly different across groups.

Table 1.

Baseline (about age 20) and early-course characteristics for 156 men who developed DSM-IV AUDs (ages 20–50) divided into groups based on problems and drinking patterns (ages 50-55)a

| Group characteristics | All subjects (N = 156) M (SD) or % | Group 1 Low-risk drinking (n = 25, 16.0%) M (SD) or % | Group 2 High-risk drinking (n = 57, 36.5%) M (SD) or % | Group 3 DSM-5 AUD (n = 59, 37.8%) M (SD) or % | Group 4 Abstinent (n = 15, 9.6%) M (SD) or % | F or χ2 | Effect sizeb,c |

| Demography | |||||||

| Age at baseline, years | 22.7 (1.93) | 23.0 (1.97) | 22.9 (1.86) | 22.3 (1.81) | 23.2 (2.40) | 1.30 | .035b |

| Race, % European American | 98.1% | 100.0% | 96.5% | 978.3% | 100.0% | 1.56 | .100c |

| Education, years | 15.4 (1.33) | 15.6 (1.58) | 15.6 (1.46) | 15.3 (1.12) | 15.3 (1.16) | 0.61 | .012b |

| Religion, % yes | 79.5% | 80.0% | 77.2% | 78.0% | 93.3% | 2.04 | .115c |

| Married, % yes | 13.5% | 8.0% | 17.5% | 11.9% | 13.3% | 1.58 | .100c |

| Alcohol-related items | |||||||

| Alcohol challenge SHAS LR | -0.10 (0.74) | 0.07 (0.69) | -0.18 (0.73) | -0.08 (0.81) | -0.18 (0.55) | 0.71 | .014b |

| Usual drinks/occasion, 6 mo. | 3.4 (1.45) | 3.6 (1.52) | 3.1 (1.23) | 3.7 (1.61) | 3.4 (1.24) | 1.85 | .035b |

| Usual frequency/month, 6 mo. | 10.4 (5.97) | 8.5 (4.84) | 10.4 (6.18) | 11.0 (6.16) | 11.1 (6.06) | 1.05 | .020b |

| Pre-baseline alcohol problem ever, % yes | 68.6% | 64.0% | 61.4% | 78.0% | 66.7% | 4.04 | .163c |

| Pre-baseline alcohol problems, number | 1.6 (1.52) | 1.7 (1.57) | 1.3 (1.32) | 1.9 (1.60) | 1.5 (1.68) | 1.49 | .029b |

| Family history DSM-IV AUD, % yes | 64.7% | 60.0% | 66.7% | 59.3% | 86.7% | 4.26 | .167c |

| Drug-related items | |||||||

| Cannabinol use, % yes | 72.4% | 68.0% | 70.2% | 72.9% | 86.7% | 1.92 | .112c |

| Amphetamine use, % yes | 34.6% | 32.0% | 36.8% | 32.2% | 40.0% | 0.54 | .059c |

| Any drug problem ever, % yes | 23.7% | 16.0% | 19.3% | 28.8% | 33.3% | 3.05 | .145c |

| No. drug problems ever, % yes | 0.4 (0.79) | 0.3 (0.80) | 0.3 (0.67) | 0.4 (1.12) | 0.6 (1.12) | 0.94 | .018b |

| Externalizing and internalizing | |||||||

| Mental health worker, % yes | 17.3% | 8.0% | 21.1% | 15.3% | 26.7% | 3.16 | .143c |

| Ever depressed, % yes | 10.3% | 8.0% | 8.8% | 13.6% | 6.7% | 1.18 | .009c |

| TPQ Novelty Seekingd | 16.9 (4.79) | 16.4 (4.13) | 16.9 (4.28) | 16.8 (5.21) | 18.2 (6.10) | 0.46 | .009b |

| Zuckerman Sensation Seekingd | 21.7 (5.08) | 21.6 (4.81) | 21.9 (4.97) | 21.6 (5.45) | 21.7 (4.92) | 0.04 | .001b |

| Karolinska Impulsivityd | 47.8 (5.16) | 47.9 (5.20) | 48.1 (499) | 47.6 (5.41) | 47.2 (5.14) | 0.16 | .003b |

Notes: There were no significant differences across groups in Table 1. DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; AUD = alcohol use disorder; SHAS = Subjective High Assessment Scale; LR = level of response to alcohol from an alcohol challenge (lower LR values = lower LR); mo. = month; no. = number; TPQ = Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire.

DSM-IV AUD = alcohol use disorder (abuse or dependence) from the DSM-IV; DSM-5 AUD = alcohol use disorder from the DSM-5 ;

effect sizes for analyses of variance: partial eta square (ηp2) (.01 = small, .06 = medium, .14 = large);

effect sizes for chi-squares: Cohen w (.10 = small, . 30 = medium, .50 = large);

assessed at age 35.

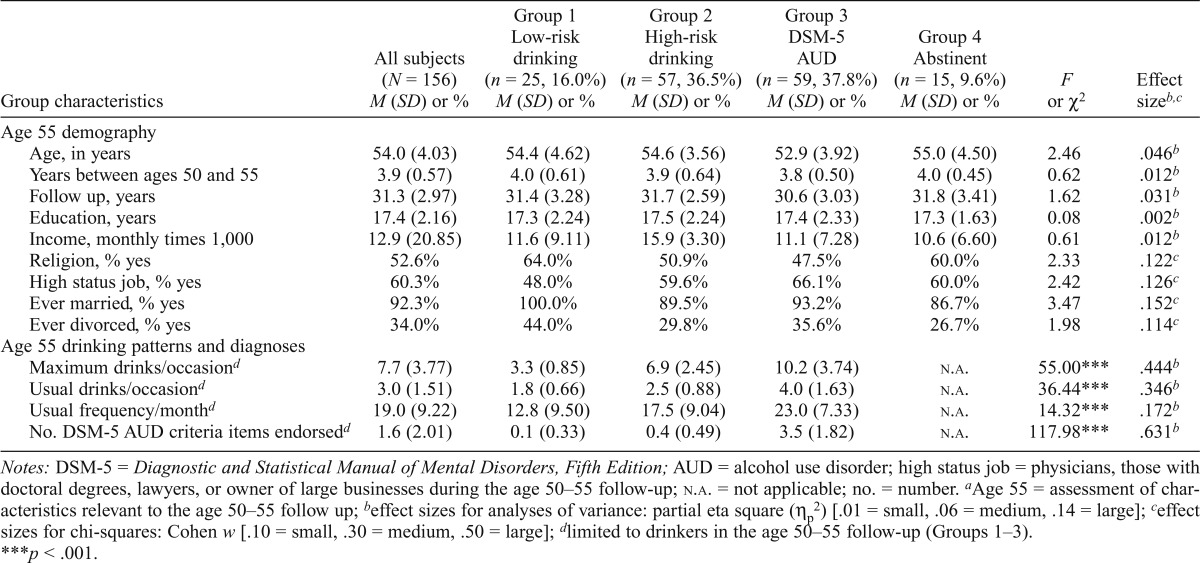

Table 2 describes age 55 demography and alcohol-related variables across the four age 55 outcome groups. Like baseline characteristics in Table 1, the outcome groups did not differ on current demography. Reflecting the outcome group definitions, alcohol quantities and frequencies increased stepwise across Groups 1–3, with Group 3 probands averaging 3.5 of 11 possible DSM-5 AUD criteria during ages 50–55.

Table 2.

| Group characteristics | All subjects (N = 156) M (SD) or % | Group 1 Low-risk drinking (n = 25, 16.0%) M (SD) or % | Group 2 High-risk drinking (n = 57, 36.5%) M (SD) or % | Group 3 DSM-5 AUD (n = 59, 37.8%) M (SD) or % | Group 4 Abstinent (n = 15, 9.6%) M (SD) or % | F or χ2 | Effect sizeb,c |

| Age 55 demography | |||||||

| Age, in years | 54.0 (4.03) | 54.4 (4.62) | 54.6 (3.56) | 52.9 (3.92) | 55.0 (4.50) | 2.46 | .046b |

| Years between ages 50 and 55 | 3.9 (0.57) | 4.0 (0.61) | 3.9 (0.64) | 3.8 (0.50) | 4.0 (0.45) | 0.62 | .012b |

| Follow up, years | 31.3 (2.97) | 31.4 (3.28) | 31.7 (2.59) | 30.6 (3.03) | 31.8 (3.41) | 1.62 | .031b |

| Education, years | 17.4 (2.16) | 17.3 (2.24) | 17.5 (2.24) | 17.4 (2.33) | 17.3 (1.63) | 0.08 | .002b |

| Income, monthly times 1,000 | 12.9 (20.85) | 11.6 (9.11) | 15.9 (3.30) | 11.1 (7.28) | 10.6 (6.60) | 0.61 | .012b |

| Religion, % yes | 52.6% | 64.0% | 50.9% | 47.5% | 60.0% | 2.33 | .122c |

| High status job, % yes | 60.3% | 48.0% | 59.6% | 66.1% | 60.0% | 2.42 | .126c |

| Ever married, % yes | 92.3% | 100.0% | 89.5% | 93.2% | 86.7% | 3.47 | .152c |

| Ever divorced, % yes | 34.0% | 44.0% | 29.8% | 35.6% | 26.7% | 1.98 | .114c |

| Age 55 drinking patterns and diagnoses | |||||||

| Maximum drinks/occasiond | 7.7 (3.77) | 3.3 (0.85) | 6.9 (2.45) | 10.2 (3.74) | N.A. | 55.00*** | .444b |

| Usual drinks/occasiond | 3.0 (1.51) | 1.8 (0.66) | 2.5 (0.88) | 4.0 (1.63) | N.A. | 36.44*** | .346b |

| Usual frequency/monthd | 19.0 (9.22) | 12.8 (9.50) | 17.5 (9.04) | 23.0 (7.33) | N.A. | 14.32*** | .172b |

| No. DSM-5 AUD criteria items endorsedd | 1.6 (2.01) | 0.1 (0.33) | 0.4 (0.49) | 3.5 (1.82) | N.A. | 117.98*** | .631b |

Notes: DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; AUD = alcohol use disorder; high status job = physicians, those with doctoral degrees, lawyers, or owner of large businesses during the age 50–55 follow-up; n.a. = not applicable; no. = number.

Age 55 = assessment of characteristics relevant to the age 50–55 follow up;

effect sizes for analyses of variance: partial eta square (ηp2) [.01 = small, .06 = medium, .14 = large];

effect sizes for chi-squares: Cohen w [.10 = small, .30 = medium, .50 = large];

limited to drinkers in the age 50–55 follow-up (Groups 1–3).

p < .001.

The characteristics reported at age 30–50 follow-ups (regarding drinking patterns ages 20–50) and their relationships to age 50–55 outcome groups are presented in Table 3. For most alcohol-related variables, men who reported low-risk drinking (Group 1) needed the lowest number of drinks for effects (or the highest LR per drink), as well as lowest alcohol quantities, frequencies, problems, and treatment exposure at age 30–50 follow-ups. The pattern for alcohol-related variables generally increased across Groups 1–4, with the highest number of drinks for effects (lowest LR per drink), quantities, frequencies, problems, and treatment exposure for the abstinent Group 4, followed by men in Group 3 who fulfilled criteria for DSM-5 AUDs at ages 50–55. Patterns across Groups 3 and 4 included an earlier AUD onset and greater experience with alcohol-related treatment and/or self-help groups for the abstinent Group 4. High-risk drinking (Group 2) was associated with LR values and alcohol histories between Group 1 and Groups 3 and 4.

The lower portion of Table 3 lists the age 20–50 patterns across groups regarding drug-related items. Most men had experience with illicit drugs during those follow-ups, but the only significant group difference was for the prevalence of cannabis use disorders, with the lowest values for Group 1 and the highest for Group 4.

The analyses next turned to an evaluation of how the nine variables from the age 30–50 follow-ups that significantly differentiated across the groups in Table 3 related to age 50–55 outcome groups when considered in the same analysis. Because the two SRE measures correlated at .66, and the number of DSM-IV AUD criterion items endorsed and DSM-IV dependence diagnoses correlated at .69, to minimize multicollinearity among the four variables only SRE-T and numbers of AUD items were used in the regression analyses. Five of the remaining seven variables from Table 3 contributed significantly to any regression analysis related to age 50–55 outcomes. Low-risk drinking (Group 1) was related to prior lower drinking frequencies; high-risk drinking (Group 2) was related to needing fewer drinks for effects (i.e., higher LRs per drink) and an older AUD onset; DSM-5 AUDs (Group 3) were related to higher prior drinking frequencies and the absence of prior treatment and/or self-help group participation; and abstinence (Group 4) was related to needing the most drinks for effects (i.e., the lowest LR), higher odds ratios for prior treatment or self-help participation, and prior cannabis use disorders.

Thus, the most consistent predictors of age 50–55 outcomes were LR, prior drinking frequencies, and having received prior help for drinking problems, each of which contributed significantly to two of the four regression analyses in Table 4. It is worth noting that although the odds ratio for the numbers of DSM items endorsed for Group 4 was not significant, the value is actually greater than 1 but appears lower in the table because of a suppressor effect in the regression analysis.

Discussion

This article presents the age 50–55 outcomes for 156 men who developed an AUD during the initial 30 years of the SDPS, as well as predictors of those outcomes. Contrary to Hypothesis 1, only 10% of these men were abstinent from alcohol during ages 50–55, and 16% reported low-risk drinking. The remaining 74% either fulfilled DSM-5 AUD criteria or reported risky drinking. Although these probands had impressive educations and incomes, the data document the tenacity of alcohol-related problems when individuals enter their sixth life decade.

These results and the study by Vaillant (2003) demonstrate that many individuals with AUDs do not fit the erroneous stereotype that they are likely to be unemployed and live on the street or in public housing. The SDPS began with students and nonacademic staff at UCSD and their earlier high functioning predicted impressive achievements despite their AUDs. Yet, as shown in Table 3, between ages 20 and 50 these men had clearly filled AUD criteria, reporting 13–16 maximum drinks per occasion and experiencing 4–6 of the 11 DSM-IV AUD items. The inaccurate AUD stereotype is often shared by health care deliverers who might be reluctant to gather alcohol or drug problem histories from affluent and well-educated patients and to intervene when appropriate. These data support the contention that—regardless of social status, income, and age—all patients should be screened for substance intake patterns and related problems.

Regarding Hypothesis 2, only 16% (Group 1) demonstrated sustained “controlled drinking” over the 5 years with alcohol quantities in the low-risk range (Dawson et al., 2012; NIAAA, 2010). Although short-term, low-risk drinking is common (Dawson et al., 2007; Ilgen et al., 2008; Schuckit et al., 1997), our findings are consistent with other studies that found less than 20% of individuals with alcohol dependence maintained controlled drinking over extended periods (Helzer et al., 1985; Ilgen et al., 2008; Maisto et al., 2007). As predicted, such nonproblematic outcomes are most likely in men who were more sensitive to alcohol (i.e., had higher LRs) and had lower past drinking quantities, frequencies, and alcohol problems (Larm et al., 2010; Maisto et al., 2007; Mann et al., 2005; Trim et al., 2013). This profile might help identify individuals for whom long-term controlled drinking might be an appropriate option.

As predicted in Hypothesis 3, high-risk drinkers (Group 2) reflected earlier alcohol-related characteristics that were between those that predicted low-risk drinking and the higher quantities and problems that related to continued AUDs in Group 3 and abstinence in Group 4. The Nagelkerke’s Pseudo R2s in Table 4 indicate that the age 20–50 independent variables predicted Group 2 less well than the other outcomes, raising the question of whether some alcohol problems went unreported by this group. Even in the absence of multiple alcohol problems, heavier drinking is not optimal because it carries elevated risks for cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancers, and other adverse health outcomes that are likely to contribute to a shortened life span (Ferreira & Weems, 2008; Holahan et al., 2015; Lundin et al., 2015; McCaul et al., 2010).

Persistent abstinence (Group 4) was not only relatively rare but was also consistent with Hypothesis 4 and several other studies (e.g., Dawson et al., 2012; Helzer et al., 1985; Vaillant, 2003). These men had the lowest LR to alcohol and reported the highest alcohol quantities, problems, and rates of alcohol dependence. More research is needed, but one possible explanation for this finding is that experiencing greater alcohol-related problems, perhaps as a consequence of a lower LR to alcohol, may have contributed to men in Group 4 seeking help, and their exposure to treatments (many of which are abstinence oriented) may have made abstinence especially acceptable to members of Group 4. Their cannabis-related problems may have also increased the likelihood of entering substance-related programs.

Table 4 used a binary logistic regression analysis to evaluate how the predictors of group membership operated when considered in the same analyses. Focusing primarily on statistically significant findings in Table 4, a lower number of drinks needed for effects on the SRE (or a higher LR per drink) was associated with a lower likelihood of being categorized as a high-risk drinker at age 50–55, and the need for more drinks for effects (or a lower LR per drink) was associated with a greater likelihood of being abstinent during the age 50–55 follow-up. Although not statistically significant, the pattern in Table 4 indicated the possibility that the need for more drinks for effects (a lower LR) might have increased the chances of meeting criteria for an AUD on follow up but decreased the chances of falling into the low-risk drinking category. Drinking frequency also contributed significantly to two regression analyses, with prior lower frequencies robustly predicting low-risk drinking and prior higher frequencies indicating a higher risk for meeting DSM-5 AUD criteria after age 50. Prior frequencies might be a measure of the importance, or salience, of alcohol to probands in these outcome groups. Past experience with formal treatment or self-help groups was significantly associated with later abstinence and was less likely to be seen in participants with active DSM-5 AUDs during the age 50–55 follow-up. Later onset AUDs predicted only high-risk drinking in Table 4 and may have related to the development of an AUD at a time with greater maturity and life experiences, which, in turn, might be associated with less likelihood of alcohol-related life problems even in the context of continued risky drinking.

Cannabis use disorder histories also significantly predicted one outcome, abstinence, perhaps reflecting cannabis-related interference with cognitive functioning in AUDs that might contribute to more severe alcohol problems, as proposed in a recent article (Schuckit et al., 2017), and/or may have contributed to the probability of seeking help. More research will be needed with additional populations of older individuals with AUDs to determine whether these findings are replicable and apply to other samples of older individuals with histories of AUDs.

The current data also generate some thoughts regarding DSM AUD approaches over the years. Regarding criteria for Group 3, we are aware that since 1987 (DSM-III-R), remission could only be diagnosed in the absence of endorsement of any DSM criterion items. Thus, earlier analyses attempted to define continued AUDs as endorsement of more than one DSM criterion item, with the result that Group 3 constituted 56% of the outcomes. Although those analyses identified the same predictors of outcome groups reported here, we were concerned that such a severe restriction regarding what was called remission might not fit the preferences of many current clinicians (e.g., Gastfriend et al., 2007), and we decided to use the DSM-5–based less demanding definition requiring two criterion problems for an active diagnosis (Hasin et al., 2013). There are no perfect and universally accepted definitions for remission versus active AUDs, but we feel the current approach is a reasonable compromise among possibilities.

As is true of all studies, it is important to keep the findings in perspective. The original sample was limited to non–alcohol-dependent European American and White Hispanic male college students or nonacademic staff, and additional studies are needed to demonstrate if the current results generalize to women and to other samples. Also, although the SDPS began with a relatively large population for such intense every-5-year evaluations, the current analyses focused on outcomes for men who developed AUDs, which, despite the greater than 90% 35-year overall follow-up, produced a modest 156 subjects.

Furthermore, the analyses were dependent on the existing baseline data gathered four decades ago that included information from multiple domains but offered a limited number of specific variables in each category. In addition, although data from additional informants were used for evaluations at ages 30, 35, 40, and 45, financial restrictions contributed to the decision to gather data only from probands at the two most recent assessments, with a potential for underreporting of heavy drinking and alcohol problems. Finally, it is important to remember that Table 4 presents four separate binary regression analyses, and although Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing would still be significant for the R2 values and for specific predictors with p values less than .01, predictors in Table 4 with p values less than .05 are more tenuous.

In summary, these data described the age 50–55 outcomes for 156 higher educated and accomplished men who developed an AUD during the prior 30 years. For most, their AUDs were persistent and severe, despite which their accomplishments did not fit the public stereotype of the “average alcoholic.” Their achievements and public persona in their 50s underscore the importance of clinicians screening all patients for possible AUDs, including those with high levels of life achievements. The robust predictions of alcohol problems from their LR in this and other studies offer potential promise in instituting earlier intervention programs based on tailored feedback about their vulnerability (Schuckit et al., 2016).

Conflict of Interest Statement

Marc Schuckit is a distinguished professor of psychiatry at the University of California Medical School, San Diego, where he is engaged primarily in research regarding genetic influences in alcoholism and prevention of heavy drinking in individuals carrying a predisposition toward alcohol-related conditions. He is director of the Alcohol Medical Scholars education program; received a small grant from ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research in 1988; and gave a presentation on the genetics of alcohol-related disorders to Anheuser-Busch InBev executives at Yale University in 2013 for which he received his travel costs and an honorarium.

Priscila Gongalves is a visiting scholar for a postdoctoral fellowship to work at Marc Schuckit’s research laboratory, which was funded by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). She was a scholar in the Alcohol Medical Scholars Program during 2015/2016.

Tom Smith has no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01 AA005526; the State of California for Medical Research on Alcohol and Substance Abuse through the University of California, San Francisco; and by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific andTechnological Development, CNPq (203313/2014-3).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1980. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. 3rd ed., rev. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual ofmental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: Author; 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G., Rumpf H. J., Hapke U., Meyer C., John U. Factors influencing remission from alcohol dependence without formal help in a representative population sample. Addiction. 2001;96:1327–1336. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.969132712.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.969132712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R. A., Faden V. B., Smothers B. Alcohol consumption by elderly Americans. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:884–892. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.884. doi:10.15288/jsa.2003.64.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. L., Schutte K. K., Moos R. H. Patterns and predictors of late-life drinking trajectories: A 10-year longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:254–264. doi: 10.1037/a0018592. doi:10.1037/a0018592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L. M., Schafer J. L., Kam C. M. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:330–351. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger C. R., Adolfsson R., Svrakic N. M. Mapping genes for human personality. Nature Genetics. 1996;12:3–4. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-3. doi:10.1038/ng0196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Goldstein R. B., Grant B. F. Rates and correlates of relapse among individuals in remission from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: A 3-year follow-up. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:2036–2045. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00536.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Goldstein R. B., Ruan W. J., Grant B. F. Correlates of recovery from alcohol dependence: A prospective study over a 3-year follow-up interval. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:1268–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01729.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01729.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M. P., Weems M. K. Alcohol consumption by aging adults in the United States: Health benefits and detriments. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108:1668–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.07.011. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastfriend D. R., Garbutt J. C., Pettinati H. M., Forman R. F. Reduction in heavy drinking as a treatment outcome in alcohol dependence. Journal of SubstanceAbuseTreatment. 2007;33:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.09.008. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Goldstein R. B., Saha T. D., Chou S. P., Jung J., Zhang H., Hasin D. S. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzerath L., Faden V, Zakhari S., Warren K. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism report on moderate drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:829–847. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128382.79375.b6. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000128382.79375.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D. S., O’Brien C. P., Auriacombe M., Borges G., Bucholz K., Budney A., Grant B. F. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: Recommendations and rationale. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:834–851. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer J. E., Robins L. N., Taylor J. R., Carey K., Miller R. H., Combs-Orme T., Farmer A. The extent of long-term moderate drinking among alcoholics discharged from medical and psychiatric treatment facilities. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1985;312:1678–1682. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506273122605. doi:10.1056/NEJM198506273122605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock M., Easton C., Bucholz K. K., Schuckit M, Hessel-brock V. A validity study of the SSAGA: A comparison with the SCAN. Addiction. 1999;94:1361–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913618.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C. J., Schutte K. K., Brennan P. L., Holahan C. K., Moos R. H. Drinking level, drinking pattern, and twenty-year total mortality among late-life drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:552–558. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.552. doi:10.15288/jsad.2015.76.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen M. A., Wilbourne P. L., Moos B. S., Moos R. H. Problem-free drinking over 16 years among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.006. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T., Koenig L. B., Howell D. N., Wood P, K., Haber J. R. Drinking trajectories from adolescence to the fifties among alcohol-dependent men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:859–869. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.859. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larm P., Hodgins S., Tengström A., Larsson A. Trajectories of resilience over 25 years of individuals who as adolescents consulted for substance misuse and a matched comparison group. Addiction. 2010;105:1216–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02914.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin A., Mortensen L. H., Halldin J., Theobald H. The relationship of alcoholism and alcohol consumption to all-cause mortality in forty-one-year follow-up of the Swedish REBUS sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:544–551. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.544. doi:10.15288/jsad.2015.76.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto S. A., Clifford P, R., Stout R. L., Davis C. M. Moderate drinking in the first year after treatment as a predictor of three-year outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:419–427. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.419. doi:10.15288/jsad.2007.68.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K., Schäfer D. R., Längle G., Ackermann K., Croissant B. The long-term course of alcoholism, 5, 10 and 16 years after treatment. Addiction. 2005;100:797–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01065.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul K. A., Almeida O. P., Hankey G. J., Jamrozik K., Byles J. E., Flicker L. Alcohol use and mortality in older men and women. Addiction. 2010;105:1391–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02972.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon V. V., Schuckit M. A., Chan G., Kramer J. R., Edenberg H. J., Bender A. K., et al. Familial influences on abstinent remission from alcohol use disorder in relatives of treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent probands. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2017 doi: 10.1111/add.13890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molander R. C., Yonker J. A., Krahn D. D. Age-related changes in drinking patterns from mid-to older age: Results from the Wisconsin longitudinal study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1182–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01195.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Brennan P. L., Schutte K. K., Moos B. S. Social and financial resources and high-risk alcohol consumption among older adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:646–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01133.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Moos B. S. Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission from alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:212–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01310.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Rethinking drinking: Alcohol and your health. NIH Publication No. 15-3770. 2010 Retrieved from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/rethinkingdrinking/rethinking_drinking.pdf.

- Penick E. C., Knop J., Nickel E. J., Jensen P., Manzardo A. M., Lykke-Mortensen E., Gabrielli W. F., Jr Do premorbid predictors of alcohol dependence also predict the failure to recover from alcoholism? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:685–694. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.685. doi:10.15288/jsad.2010.71.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott C. A., Kendler K. S. Associations between marital status and alcohol consumption in a longitudinal study of female twins. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:589–604. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.589. doi:10.15288/jsa.2001.62.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray L. A., Audette A., DiCristoforo S., Odell K., Kaiser A., Hutchison K. E. Behavioral laboratory and genetic correlates of low level of response to alcohol [Abstract 490] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31, Supplement. 2007;S2:131a. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Zatonski W., Taylor B., Anderson P. Epidemiology and alcohol policy in Europe. Addiction, 106, Supplement. 2011;1:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03326.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L. N., Helzer J. E., Croughan J., Ratcliff K. S. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalling D., Asberg M. Biological and psychological correlates of impulsiveness and monotony in avoidance. In: Strelau J., Farley F. J., Gale A., editors. The biological bases of personality and behavior, Vol. 1: Theories, measurement techniques, and development. New York, NY: Hemisphere Publishing Corp/Harper & Row Publishers; 1985. pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M. A., Danko G. P., Smith T. L. Patterns of drug-related disorders in a prospective study of men chosen for their family history of alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:613–620. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.613. doi:10.15288/jsa.2004.65.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M. A., Gold E. O. A simultaneous evaluation of multiple markers of ethanol/placebo challenges in sons of alcoholics and controls. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:211–216. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800270019002. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800270019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M. A., Smith T. L. An 8-year follow-up of 450 sons of alcoholic and control subjects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:202–210. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030020005. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M. A., Smith T. L. Onset and course of alcoholism over 25 years in middle class men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;113:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.017. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M. A., Smith T. L., Clausen P., Fromme K., Skidmore J., Shafir A., Kalmijn J. The low level of response to alcohol-based heavy drinking prevention program: One-year follow-up. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77:25–37. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M. A., Smith T. L., Kalmijn J. A. The patterns of drug and alcohol use and associated problems over 30 years in 397 men. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:227–234. doi: 10.1111/acer.12220. doi:10.1111/acer.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M. A., Smith T. L., Shafir A., Clausen P., Danko G., Gongalves P. D., Bucholz K. K. Predictors of patterns of alcohol-related blackouts over time in youth from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism: The roles of genetics and cannabis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78:39–48. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.39. doi:10.15288/jsad.2017.78.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M. A., Tipp J. E., Smith T. L., Bucholz K. K. Periods of abstinence following the onset of alcohol dependence in 1,853 men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:581–589. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.581. doi:10.15288/jsa.1997.58.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte K. K., Moos R. H., Brennan P. L. Predictors of untreated remission from late-life drinking problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:354–362. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.354. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C., Moos R. H., Finney J. W., Lesar M. D. Long-term outcomes of alcohol use disorders: Comparing untreated individuals with those in Alcoholics Anonymous and formal treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:529–540. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.529. doi:10.15288/jsa.2000.61.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trim R. S., Schuckit M. A., Smith T. L. Predictors of initial and sustained remission from alcohol use disorders: Findings from the 30-year follow-up of the San Diego Prospective Study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:1424–1431. doi: 10.1111/acer.12107. doi:10.1111/acer.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upah R., Jacob T., Price R. K. Trajectories of lifetime comorbid alcohol and other drug use disorders through midlife. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:721–732. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.721. doi:10.15288/jsad.2015.76.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E. A 60-year follow-up of alcoholic men. Addiction. 2003;98:1043–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00422.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M., Kuhlman D. M. Personality and risk-taking: Common biosocial factors. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:999–1029. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00124. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]