Abstract

Objective:

Parental warmth and knowledge are protective factors against substance use, whereas parental psychological control is a risk factor. However, the interpretation of parenting and its effects on developmental outcomes may vary cross-culturally. This study examined direct and indirect effects ofthree parenting dimensions on substance use across Asian/Pacific Islander (API) and European Americans.

Method:

A community sample of 97 API and 255 European Americans were followed from Grades 6 to 12. Participants reported on parenting in Grade 7, academic achievement and externalizing behaviors in Grades 7 and 8, and substance use behaviors in Grades 7, 9, and 12.

Results:

Direct effects of parenting were not moderated by race. Overall, mother psychological control was a risk factor for substance use problems in Grade 9, whereas father knowledge was protective against alcohol use in Grade 9, substance use problems in Grades 9 and 12, and alcohol dependence in Grade 12. Moderated mediation analyses indicated significant mediational links among European Americans only: Mother knowledge predicted fewer externalizing problems in Grade 8, which in turn predicted fewer substance use problems in Grades 9 and 12. Father warmth predicted better academic achievement in Grade 8, which in turn predicted fewer substance use problems in Grades 9 and 12, as well as alcohol and marijuana dependence in Grade 12.

Conclusions:

Better academic achievement and fewer externalizing behaviors explain how positive parenting reduces substance use risk among European Americans. Promoting father knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts can reduce substance use risk among both European and API Americans.

Asian americans are the fastest growing immigrant group in the United States (Pew Research Center, 2013). Collectively, Asian/Pacific Islander (API) Americans report less substance use compared with European Americans (Price et al., 2002; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). However, substantial heterogeneity exists among API subgroups and trend data reveal increasing problematic use over time (Choi, 2008; Grant et al., 2004; So & Wong, 2006). Once initiated to drinking, APIs develop alcohol dependence symptoms more quickly than non-Hispanic Whites (Lee et al., 2011). APIs with drug use disorders also follow a more persistent course compared with non-Hispanic Whites (Xu et al., 2011). Thus, despite lower overall rates, unique intervention challenges exist among API individuals with substance use problems.

Parenting is a core socialization factor associated with adolescent substance use (Barnes et al., 2000; Baumrind, 1991) and is a common target of family-based adolescent substance use interventions (Smit et al., 2008; Spoth et al., 2001). Among Asian American youth, parent–youth relationship and parental attitudes toward substance use are significant substance use correlates (Hahm et al., 2003; Hong et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012). Cross-cultural research suggests that the interpretation and effects of parenting on developmental outcomes may vary cross-culturally (Chao & Tseng, 2002). Authoritarian parenting, which encompasses low parental warmth and high parental control, is common in Asian families (Chao 1994, 2001; Chao & Aque, 2009; Kawamura et al., 2002). Although an authoritarian parenting style is considered less than optimal in individualistic Western cultures, it has been associated with academic achievement and social–emotional adjustment in collectivistic Asian cultures (Ang, 2006; Leung et al., 1998; Li et al., 2010). This implies that parental warmth may be less of a protective factor for developmental outcomes among Asian youth, whereas parental control may be less of a risk factor.

In a recent cross-sectional study among college students, Luk et al. (2015) found that retrospective reports of parental warmth (as a protective factor) and denial of psychological autonomy (as a risk factor) were associated with alcohol problems and marijuana use among European Americans but not Asian Americans. The absence of significant associations among Asian Americans may reflect that parental warmth and denial of psychological autonomy are not capturing the most important elements of parenting that protect against substance use among Asian Americans. Parental knowledge of a child’s whereabouts and activities is a robust protective factor against adolescent substance use (Racz & McMahon, 2011) that has rarely been examined in relation to substance use among Asian Americans. Without parallel literature supporting potential cross-cultural moderation, in this article we tested parental knowledge as a consistent protective factor against substance use across European Americans and Asian Americans using prospective data.

Alternatively, the timing of specific parenting behaviors and their indirect effects on substance use may be crucial. Direct parenting effects may be particularly important during early adolescence, whereas parental influences may operate through mediators that are more proximal to substance use outcomes during late adolescence into young adulthood (Hartman et al., 2015; Kim & Neff, 2010; Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006). Given our interest in the late adolescent developmental period, the examination of mediators is warranted. Academic achievement (as a correlate of school connectedness; Niehaus et al., 2012) and externalizing problems (as a direct test of the deviance proneness pathway; Sher, 1991) were chosen as mediators because these constructs were implicated in developmental cascade models (Haller et al., 2010; Sitnick et al., 2014). Because evidence of cross-cultural moderation has focused on the effects of parenting on developmental outcomes (Chao & Tseng, 2002), tests of moderation focusing on the effects of parenting dimensions on academic achievement, externalizing behaviors, and substance use outcomes are warranted.

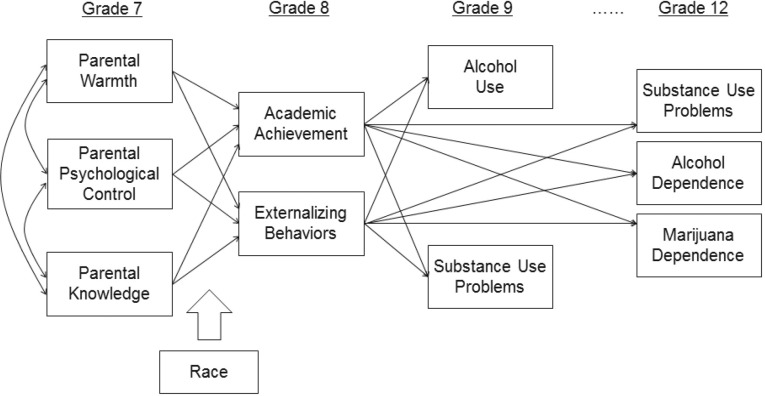

This is the first prospective study examining both direct and indirect effects of multiple parenting dimensions on substance use behaviors across API and European American youth. Our conceptual model is presented in Figure 1. First, we tested whether race moderated the direct effects of adolescents’ perceived parental warmth, psychological control, and knowledge in Grade 7 on five substance use outcomes in Grades 9 and 12. Second, we examined whether race moderated the effects of parenting dimensions on academic achievement and externalizing problems in Grade 8. We hypothesized that in both the moderation and moderated mediation models, the effects of parental warmth and psychological control would be moderated by race, whereas the effects of parental knowledge would be consistent across race.

Figure 1.

Conceptual moderated mediation model with race moderating the paths from parenting dimensions to academic achievement and externalizing behaviors. The direct effects of parenting dimensions in Grade 7 on five substance use outcomes in Grades 9 and 12 were modeled but were not shown in this figure. Similarly, autoregressive paths for both the mediators and the outcome variables were modeled in all analyses but were not shown in this figure.

Method

Participants and procedures

This study used data from a large community-based prospective cohort study of the development of adolescent depression and conduct problems. Participants were recruited from four public schools that were representative of the public middle school population in Seattle, WA. Initially, 2,187 students were screened for depression and conduct problems, and a stratified random sample of 807 students was invited to participate. Among those invited, 521 (64.6%) sixth graders and their parents or guardians provided consent. Participants and nonparticipants did not differ with regard to screening depression and conduct problems status. Two trained interviewers conducted in-home interviews. Participants were followed from 6th to 12th grade. This study was approved by the University of Washington’s Human Subjects Review Board.

The full sample (N = 521) was racially diverse (48.9% White, 28.4% African American, 18.6% API, and 4.0% Native American). Guided by our research questions, we restricted the sample to API and European Americans, resulting in an analytic sample of 352 youth (53.1% male, n = 187; 27.6% API, n = 97). The mean age in Grade 6 was 11.9 years (SD = 0.40). The breakdown of API ethnic subgroups was as follows: 16 Filipino, 16 Vietnamese, 15 Chinese, 12 Japanese, 9 Pacific Islanders, 9 Southeast Asian, 8 Samoan, 3 East Indian, 2 Korean, and 7 other Asian. About 66% of API participants (n = 64) were born in the United States.

Measures

Parenting.

Parenting was only measured in Grade 7. Adolescents reported perceived parenting behaviors by their mother (or female caregiver) and father (or male caregiver) with items from Barber and Olsen’s (1997) socialization in context model. Parental warmth was measured by the 10-item acceptance subscale of the Child Report of Parent Behavior Inventory (Schaefer, 1965). Parental psychological control was measured by the eight-item psychological control scale (Barber, 1996). Parental knowledge was measured by the five-item parental monitoring scale (Brown et al., 1993). Response options for parental warmth and psychological control were 0 (not like him/her), 1 (somewhat like him/ her), and 2 (a lot like him/her). Response options for parental knowledge were 0 (does not know), 1 (knows a little), and 2 (knows a lot). Two identical versions were administered to assess mother and father parenting separately. Because the parental psychological control item “always tries to change how I feel or think about things” was non-invariant across race (Luk et al., 2016), this item was excluded from the current analyses, yielding a total of 44 parenting items (22 items per parent). Mean scores for each parenting dimension were calculated. Cronbach’s a’s for mother warmth, psychological control, and knowledge were .92, .93, and .80, respectively, for Europeans and .93, .86, and .76, respectively, for APIs. Cronbach’s a’s for father warmth, psychological control, and knowledge were .94, .87, and .87, respectively, for Europeans and .94, .89, .85, respectively, for APIs.

Academic achievement.

Academic achievement was measured in Grades 7 and 8 using grade point average obtained through school records.

Externalizing problems.

Externalizing problems were measured in Grades 7 and 8 using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a widely used parent-report measure of internalizing and externalizing problems and related behaviors (Achenbach, 1991). The reliability and validity of the CBCL are well established (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; Doyle et al., 1997; Hudziak et al., 2004).

Alcohol use.

Lifetime alcohol use in Grades 7 and 9 was measured as a binary variable (0 = has never used alcohol and 1 = has ever used alcohol).

Substance use problems.

A 23-item adapted version of the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; Miller et al., 2002; White & Labouvie, 1989) was used to assess past-year alcohol and marijuana-related negative consequences in Grades 7, 9, and 12. RAPI responses were coded as zeros for youth who did not report alcohol or marijuana use in the past 6 months. Response options ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (more than 10 times).

Alcohol and marijuana dependence.

The Voice Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) alcohol and marijuana abuse modules were self-administered by adolescents in Grade 12 to assess past-year alcohol and marijuana dependence. Computer-assisted technology was used to grant youth greater privacy and anonymity in responding to sensitive questions. The reliability of the Voice DISC is comparable to that of other DISC versions (Lucas, 2003). Because of substantial overlap between abuse and dependence diagnoses (correlated at .80 for alcohol diagnoses and .77 for marijuana diagnoses), only alcohol and marijuana dependence were included as outcomes (0 = negative diagnosis, 1 = intermediate diagnosis, and 2 = positive diagnosis). An intermediate diagnosis is assigned if the adolescent met at least half of the symptom criteria but did not meet full criteria (a “subthreshold” diagnosis). A positive diagnosis is assigned if the adolescent met full symptom criteria.

Covariates.

Age, gender, parental substance use, and baseline substance use reported by adolescents were included as covariates in all full models. Adolescent-reported parental substance use variables were measured using single items. For models predicting alcohol use, mother or father alcohol use (measured as “mother herself drank a lot” or “father himself drank a lot” for the respective model) and any alcohol use at Grade 7 were included as covariates. For models predicting alcohol problems and dependence, single-item measures of mother or father drinking problems and RAPI scores at Grade 7 were included as covariates. For models predicting marijuana dependence, single-item measures of mother or father drug problems and any marijuana use at Grade 7 were included as covariates.

Data analysis plan

Descriptive statistics and moderated mediation analyses were conducted in SPSS and Mplus 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014). Attrition analyses indicated 10% missing data in academic achievement and externalizing behaviors in Grade 8 and 9% missing data in any substance use outcomes in Grades 9 and 12. The pattern of missing data in mediators and substance use outcomes did not differ by age, gender, and baseline alcohol and marijuana use. Compared with European Americans, API Americans were more likely to have missing data in externalizing behaviors (16% vs. 8%), Χ2(1) = 5.73,p < .05. Missing data in academic achievement and substance use outcomes did not differ by race. Multiple imputation with 30 data sets was used to handle missing data using Bayesian analysis (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010; Schafer & Graham, 2002). All models with significant findings were run using both imputed and non-imputed data sets. Because no significant variations were found, we reported final analyses using multiple imputation with the full analytic sample.

Regression analyses took into account the varied distribution of substance use outcomes. Logistic regressions were used to model lifetime alcohol use. Substance use problems were positively skewed and were modeled using negative binomial models, which yielded the lowest Bayesian information criterion values relative to linear regression or alternative count models (Atkins et al., 2013). Alcohol and marijuana dependence were modeled using ordinal logistic regressions. The use of a multiple-group approach to test moderation hypotheses was explored in preliminary analyses but was found to be incompatible with simultaneous modeling of count outcomes and multiple imputation procedures. Thus, we tested moderation by creating interaction terms between parenting dimensions and race in predicting substance use.

Because parenting questionnaires were only administered in Grade 7, we treated this time point as the study baseline. As mother and father parenting may be differentially associated with internalizing and externalizing behaviors (Luk et al., 2010; Quach et al., 2015), mother and father parenting effects on substance use were analyzed in separate models. To test moderation effects, we computed three Parenting x Race interaction terms for each parent, yielding a total of six interaction terms. Guided by our main research questions, tests of moderated mediation focused on the paths from parenting dimensions to the mediators only, which is known as a “first-stage moderated model” (Edwards & Lambert, 2007).

To test cross-cultural moderation of the direct effects of parenting on substance use, analyses followed three steps. First, we tested whether each set of Parenting Dimension × Race interaction effects significantly predicted substance use outcomes one at a time (e.g., mother warmth, race, and Mother Warmth × Race) after controlling for covariates (age, gender, and parental substance use) and baseline substance use. Then, we built the full model by simultaneously including three parenting dimensions as predictors, along with any significant Parenting × Race interaction effects identified in the first step. Last, we fitted a trimmed model in which all the nonsignificant (p > .05) covariates were dropped. Moderated mediation models were built using a similar three-step approach.

Moderated mediation effects and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using the product of coefficients method in RMediation (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011), which provides the best balance of type I error and statistical power relative to the casual steps and difference in coefficients approaches (MacKinnon et al., 2002). Regression coefficients, standard errors, and the correlation between regression coefficients were obtained using the full sample and were entered into RMediation. For paths from parenting dimensions to the mediators, we probed significant interactions and obtain group-specific regression coefficients and standard errors by recoding race (from European = 0 and API = 1 to API = 0 and European = 1). Regression coefficient estimates and standard errors for paths from the mediators to the substance use outcomes were equivalent across racial groups. Autoregressive paths for both the mediators and the outcome variables were controlled for in all analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics

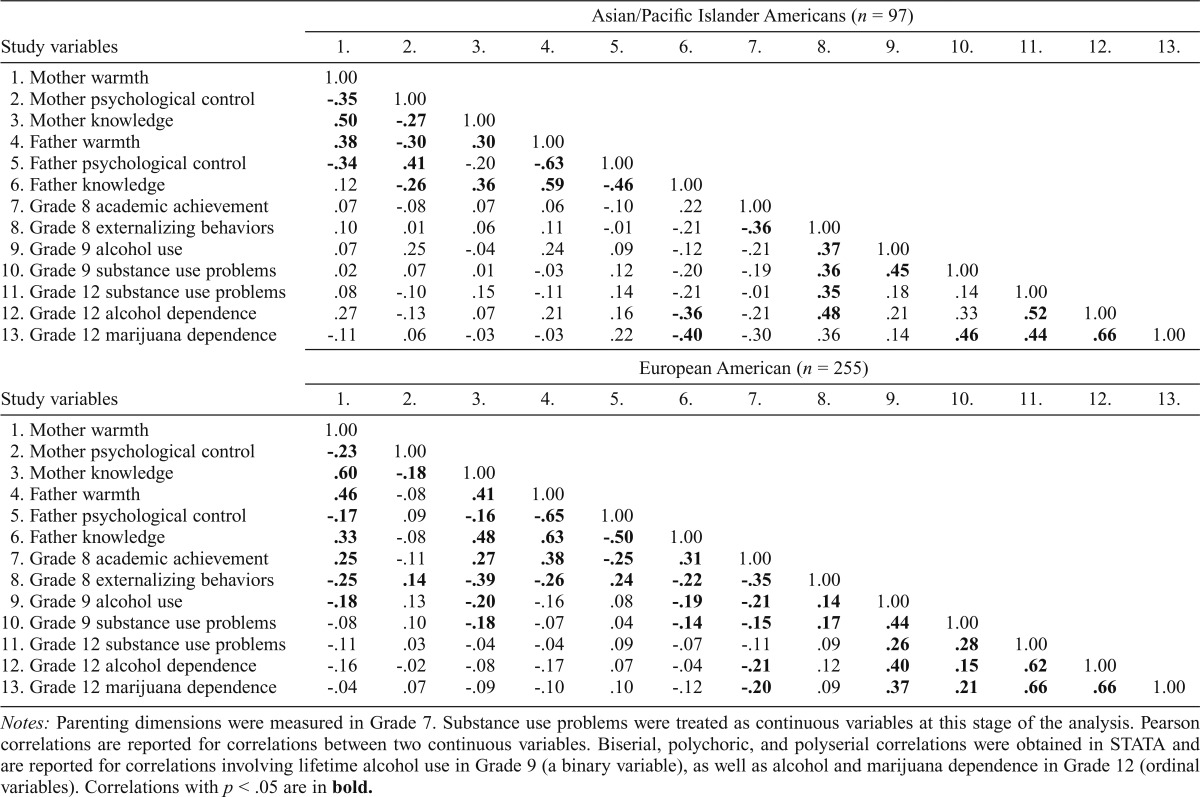

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations by race are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Consistent across mother and father parenting, European Americans reported higher parental warmth and knowledge but lower psychological control than API Americans. European Americans were significantly more likely than API Americans to meet criteria for alcohol dependence (30.0% vs. 14.0%) and marijuana dependence (28.3% vs. 12.8%) in Grade 12. Among European Americans, mother warmth, mother knowledge, and father knowledge were inversely associated with alcohol use in Grade 9. Similarly, mother and father knowledge were inversely associated with substance use problems in Grade 9. Among API Americans, father knowledge was inversely associated with alcohol and marijuana dependence in Grade 12.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study variables among Asian/Pacific Islander and European American youth

| Study variables | Asian/Pacific Islander |

European Americans |

||||

| Americans (n = 97) |

(n = 255) |

|||||

| M (n) | SD (%) | M (n) | SD (%) | t or χ2 | p | |

| Mother warmth | 1.35 | 0.56 | 1.60 | 0.45 | 4.03 | .000 |

| Mother psychological control | 0.81 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.61 | -3.10 | .002 |

| Mother knowledge | 1.41 | 0.48 | 1.66 | 0.42 | 4.39 | .000 |

| Father warmth | 1.24 | 0.61 | 1.50 | 0.53 | 3.64 | .000 |

| Father psychological control | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.45 | -4.51 | .000 |

| Father knowledge | 1.18 | 0.61 | 1.35 | 0.60 | 2.20 | .028 |

| Grade 8 academic achievement | 2.94 | 0.93 | 2.90 | 0.81 | -0.37 | .712 |

| Grade 8 externalizing behaviors | 5.05 | 5.52 | 6.10 | 7.11 | 1.21 | .226 |

| Grade 9 alcohol use | ||||||

| Ever use any alcohol | (21) | (21.6%) | (71) | (27.8%) | (1.40) | .278 |

| Grade 9 substance use problems | 0.63 | 2.67 | 1.59 | 5.50 | 1.65 | .100 |

| Grade 12 substance use problems | 2.93 | 7.37 | 4.40 | 8.15 | 1.56 | .120 |

| Grade 12 alcohol dependence | ||||||

| Negative diagnosis | (74) | (86.0%) | (163) | (70.0%) | (8.53) | .014 |

| Intermediate diagnosis | (9) | (10.5%) | (54) | (23.1%) | ||

| Positive diagnosis Grade | (3) | (3.5%) | (16) | (6.9%) | ||

| 12 marijuana dependence | ||||||

| Negative diagnosis | (75) | (87.2%) | (167) | (71.7%) | (8.40) | .015 |

| Intermediate diagnosis | (6) | (7.0%) | (40) | (17.1%) | ||

| Positive diagnosis | (5) | (5.8%) | (26) | (11.2%) | ||

Notes: Parenting dimensions were measured in Grade 7. For continuous outcomes, means and standard deviations were reported, and t tests were used to compare differences by race. For categorical outcomes, frequencies and valid percentages were reported, and chi-square tests were used to compare differences by race.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among parenting dimensions and substance use variables by race

| Asian/Pacific Islander Americans (n = 97) |

|||||||||||||

| Study variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. |

| 1. Mother warmth | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Mother psychological control | -.35 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3. Mother knowledge | .50 | -.27 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 4. Father warmth | .38 | -.30 | .30 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 5. Father psychological control | -.34 | .41 | -.20 | -.63 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 6. Father knowledge | .12 | -.26 | .36 | .59 | -.46 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 7. Grade 8 academic achievement | .07 | -.08 | .07 | .06 | -.10 | .22 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 8. Grade 8 externalizing behaviors | .10 | .01 | .06 | .11 | -.01 | -.21 | -.36 | 1.00 | |||||

| 9. Grade 9 alcohol use | .07 | .25 | -.04 | .24 | .09 | -.12 | -.21 | .37 | 1.00 | ||||

| 10. Grade 9 substance use problems | .02 | .07 | .01 | -.03 | .12 | -.20 | -.19 | .36 | .45 | 1.00 | |||

| 11. Grade 12 substance use problems | .08 | -.10 | .15 | -.11 | .14 | -.21 | -.01 | .35 | .18 | .14 | 1.00 | ||

| 12. Grade 12 alcohol dependence | .27 | -.13 | .07 | .21 | .16 | -.36 | -.21 | .48 | .21 | .33 | .52 | 1.00 | |

| 13. Grade 12 marijuana dependence | -.11 | .06 | -.03 | -.03 | .22 | -.40 | -.30 | .36 | .14 | .46 | .44 | .66 | 1.00 |

| European American (n = 255) |

|||||||||||||

| Study variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. |

| 1. Mother warmth | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Mother psychological control | -.23 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3. Mother knowledge | .60 | -.18 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 4. Father warmth | .46 | -.08 | .41 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 5. Father psychological control | -.17 | .09 | -.16 | -.65 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 6. Father knowledge | .33 | -.08 | .48 | .63 | -.50 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 7. Grade 8 academic achievement | .25 | -.11 | .27 | .38 | -.25 | .31 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 8. Grade 8 externalizing behaviors | -.25 | .14 | -.39 | -.26 | .24 | -.22 | -.35 | 1.00 | |||||

| 9. Grade 9 alcohol use | -.18 | .13 | -.20 | -.16 | .08 | -.19 | -.21 | .14 | 1.00 | ||||

| 10. Grade 9 substance use problems | -.08 | .10 | -.18 | -.07 | .04 | -.14 | -.15 | .17 | .44 | 1.00 | |||

| 11. Grade 12 substance use problems | -.11 | .03 | -.04 | -.04 | .09 | -.07 | -.11 | .09 | .26 | .28 | 1.00 | ||

| 12. Grade 12 alcohol dependence | -.16 | -.02 | -.08 | -.17 | .07 | -.04 | -.21 | .12 | .40 | .15 | .62 | 1.00 | |

| 13. Grade 12 marijuana dependence | -.04 | .07 | -.09 | -.10 | .10 | -.12 | -.20 | .09 | .37 | .21 | .66 | .66 | 1.00 |

Notes: Parenting dimensions were measured in Grade 7. Substance use problems were treated as continuous variables at this stage of the analysis. Pearson correlations are reported for correlations between two continuous variables. Biserial, polychoric, and polyserial correlations were obtained in STATA and are reported for correlations involving lifetime alcohol use in Grade 9 (a binary variable), as well as alcohol and marijuana dependence in Grade 12 (ordinal variables). Correlations with p < .05 are in bold.

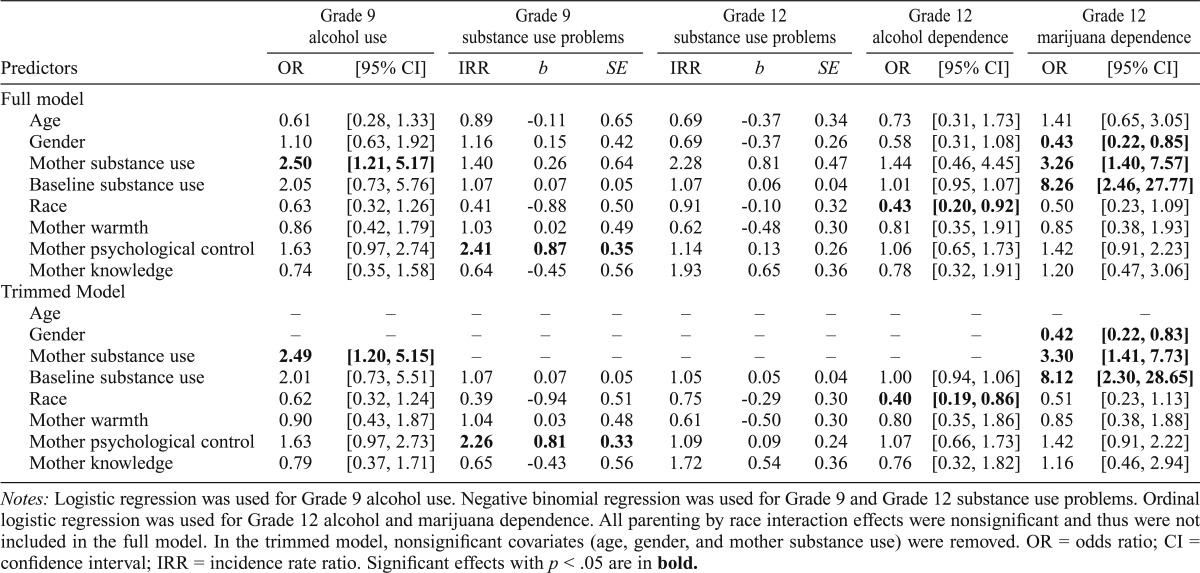

Direct parenting effects: Tests of moderation

Preliminary models indicated no significant Parenting × Race interaction effect on any of the substance use outcomes. Thus, we only included the main effects of parenting dimensions on substance use in the full and trimmed models, which are presented in Tables 3 (mother parenting) and 4 (father parenting). Significant effects that were consistent across both models were judged to be robust and were interpreted. Mother psychological control in Grade 7 was a risk factor for substance use problems in Grade 9. Father knowledge in Grade 7 was a consistent protective factor against four substance use outcomes: alcohol use and substance use problems in Grade 9 and substance use problems and alcohol dependence in Grade 12.

Table 3.

Direct effects of mother parenting on substance use outcomes

| Grade 9 alcohol use |

Grade 9 substance use problems |

Grade 12 substance use problems |

Grade 12 alcohol dependence |

Grade 12 marijuana dependence |

||||||||

| Predictors | OR | [95% CI] | IRR | b | SE | IRR | b | SE | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] |

| Full model | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.61 | [0.28, 1.33] | 0.89 | -0.11 | 0.65 | 0.69 | -0.37 | 0.34 | 0.73 | [0.31, 1.73] | 1.41 | [0.65, 3.05] |

| Gender | 1.10 | [0.63, 1.92] | 1.16 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.69 | -0.37 | 0.26 | 0.58 | [0.31, 1.08] | 0.43 | [0.22, 0.85] |

| Mother substance use | 2.50 | [1.21, 5.17] | 1.40 | 0.26 | 0.64 | 2.28 | 0.81 | 0.47 | 1.44 | [0.46, 4.45] | 3.26 | [1.40, 7.57] |

| Baseline substance use | 2.05 | [0.73, 5.76] | 1.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.01 | [0.95, 1.07] | 8.26 | [2.46, 27.77] |

| Race | 0.63 | [0.32, 1.26] | 0.41 | -0.88 | 0.50 | 0.91 | -0.10 | 0.32 | 0.43 | [0.20, 0.92] | 0.50 | [0.23, 1.09] |

| Mother warmth | 0.86 | [0.42, 1.79] | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.49 | 0.62 | -0.48 | 0.30 | 0.81 | [0.35, 1.91] | 0.85 | [0.38, 1.93] |

| Mother psychological control | 1.63 | [0.97, 2.74] | 2.41 | 0.87 | 0.35 | 1.14 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 1.06 | [0.65, 1.73] | 1.42 | [0.91, 2.23] |

| Mother knowledge | 0.74 | [0.35, 1.58] | 0.64 | -0.45 | 0.56 | 1.93 | 0.65 | 0.36 | 0.78 | [0.32, 1.91] | 1.20 | [0.47, 3.06] |

| Trimmed Model | ||||||||||||

| Age | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gender | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.42 | [0.22, 0.83] |

| Mother substance use | 2.49 | [1.20, 5.15] | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.30 | [1.41, 7.73] |

| Baseline substance use | 2.01 | [0.73, 5.51] | 1.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.00 | [0.94, 1.06] | 8.12 | [2.30, 28.65] |

| Race | 0.62 | [0.32, 1.24] | 0.39 | -0.94 | 0.51 | 0.75 | -0.29 | 0.30 | 0.40 | [0.19, 0.86] | 0.51 | [0.23, 1.13] |

| Mother warmth | 0.90 | [0.43, 1.87] | 1.04 | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.61 | -0.50 | 0.30 | 0.80 | [0.35, 1.86] | 0.85 | [0.38, 1.88] |

| Mother psychological control | 1.63 | [0.97, 2.73] | 2.26 | 0.81 | 0.33 | 1.09 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 1.07 | [0.66, 1.73] | 1.42 | [0.91, 2.22] |

| Mother knowledge | 0.79 | [0.37, 1.71] | 0.65 | -0.43 | 0.56 | 1.72 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.76 | [0.32, 1.82] | 1.16 | [0.46, 2.94] |

Notes: Logistic regression was used for Grade 9 alcohol use. Negative binomial regression wasused for Grade 9 and Grade 12 substance use problems. Ordinal logistic regression was used for Grade 12 alcohol and marijuana dependence. All parenting by race interaction effects were nonsignificant and thus were not included in the full model. In the trimmed model, nonsignificant covariates (age, gender, and mother substance use) were removed. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; IRR = incidence rate ratio. Significant effects with p < .05 are in bold.

Table 4.

Direct effects of father parenting on substance use outcomes

| Predictors | Grade 9 alcohol use |

Grade 9 substance use problems |

Grade 12 substance use problems |

Grade 12 alcohol dependence |

Grade 12 marijuana dependence |

|||||||

| OR | [95% CI] | IRR | b | SE | IRR | b | SE | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | |

| Full model | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.55 | [0.24, 1.25] | 0.62 | -0.48 | 0.52 | 0.51 | -0.69 | 0.35 | 0.59 | [0.24, 1.43] | 1.26 | [0.56, 2.82] |

| Gender | 1.00 | [0.57, 1.74] | 1.10 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.58 | -0.55 | 0.26 | 0.49 | [0.26, 0.95] | 0.40 | [0.20, 0.80] |

| Father substance use | 1.64 | [0.89, 3.02] | 5.54 | 1.71 | 0.47 | 2.25 | 0.80 | 0.42 | 1.37 | [0.65, 2.89] | 3.39 | [1.46, 7.90] |

| Baseline substance use | 2.47 | [0.96, 6.41] | 1.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 1.00 | [0.94, 1.06] | 6.94 | [2.31, 20.83] |

| Race | 0.74 | [0.38, 1.45] | 0.40 | -0.92 | 0.48 | 0.67 | -0.40 | 0.33 | 0.43 | [0.21, 0.88] | 0.52 | [0.24, 1.13] |

| Father warmth | 1.42 | [0.64, 3.15] | 3.17 | 1.15 | 0.52 | 1.43 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 1.68 | [0.65, 4.31] | 2.56 | [0.91, 7.14] |

| Father psychological control | 0.82 | [0.36, 1.83] | 1.70 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 1.31 | 0.26 | 0.45 | 1.45 | [0.61, 3.45] | 1.79 | [0.79, 4.07] |

| Father knowledge | 0.50 | [0.25, 0.98] | 0.31 | -1.18 | 0.34 | 0.53 | -0.64 | 0.28 | 0.46 | [0.24, 0.91] | 0.54 | [0.24, 1.22] |

| Trimmed model | ||||||||||||

| Age | – | – | – | – | – | 0.59 | –0.53 | 0.35 | – | – | – | – |

| Gender | – | – | – | – | – | 0.69 | –0.38 | 0.27 | 0.54 | [0.30, 1.00] | 0.40 | [0.20, 0.78] |

| Father substance use | – | – | 4.68 | 1.54 | 0.45 | – | – | – | – | – | 3.41 | [1.45, 8.02] |

| Baseline substance use | 2.51 | [0.97, 6.47] | 1.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 1.00 | [0.94, 1.06] | 6.82 | [2.21, 20.98] |

| Race | 0.70 | [0.36, 1.36] | 0.41 | -0.90 | 0.51 | 0.67 | -0.40 | 0.36 | 0.40 | [0.20, 0.81] | 0.53 | [0.24, 1.17] |

| Father warmth | 1.45 | [0.67, 3.11] | 2.63 | 0.96 | 0.57 | 1.52 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 1.67 | [0.67, 4.12] | 2.56 | [0.91, 7.21] |

| Father psychological control | 0.81 | [0.36, 1.80] | 1.53 | 0.43 | 0.67 | 1.36 | 0.30 | 0.44 | 1.45 | [0.62, 3.39] | 1.80 | [0.79, 4.14] |

| Father knowledge | 0.52 | [0.27, 0.99] | 0.32 | -1.14 | 0.34 | 0.56 | -0.58 | 0.28 | 1.49 | [0.26, 0.92] | 0.52 | [0.23, 1.21] |

Notes: Logistic regression was used for Grade 9 alcohol use. Negative binomial regression was used for Grade 9 and Grade 12 substance use problems. Ordinal logistic regression was used for Grade 12 alcohol and marijuana dependence. All parenting by race interaction effects were nonsignificant and thus were not included in the full model. In the trimmed model, nonsignificant covariates (age, gender, and father substance use) were removed. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; IRR = incidence rate ratio. Significant effects with p < .05 are in bold.

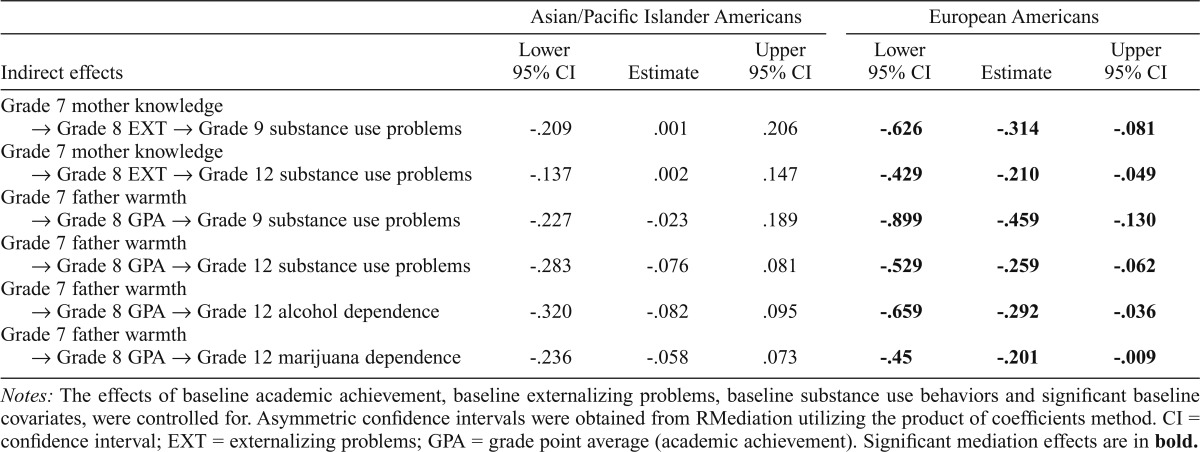

Indirect parenting effects: Tests of moderated mediation

Preliminary models indicated two significant Parenting x Race interaction effects on the mediators. First, the effect of mother knowledge in Grade 7 on externalizing problems in Grade 8 was moderated by race (b = 2.88, SE = 1.16, p = .013). Mother knowledge was protective against externalizing problems among European Americans (b = 2.46, SE = 0.83, p = .003) but not among API Americans (b = 0.42, SE = 0.87, p = .63). Second, the effect of father warmth in Grade 7 on academic achievement in Grade 8 was moderated by race (b = 0.40, SE = 0.18, p = .027). Father warmth was associated with better academic achievement among European Americans (b = 0.45, SE = 0.12, p < .001) but not among API Americans (b = 0.05, SE = 0.14, p = .73). There were no significant direct effects from parenting dimensions on the mediators that were not moderated by race.

Paths from mediators to substance use outcomes were estimated using the entire sample. In the full and trimmed indirect effects models, six paths from mediators to substance use outcomes were significant. Academic achievement in Grade 7 was protective against substance use problems in Grade 9 (IRR [incidence rate ratio] = 0.49, b = 0.72, SE = 0.29, p = .012), substance use problems in Grade 12 (IRR = 0.63, b = 0.46, SE = 0.16,p = .003), alcohol dependence in Grade 12 (OR [odds ratio] = 0.62, 95% CI [0.42, 0.91], p = .015), and marijuana dependence in Grade 12 (OR = 0.69, 95% CI [0.48, 0.99], p = .048). Externalizing problems in Grade 7 was associated with more substance use problems in Grade 9 (IRR = 1.12, b = 0.11, SE = 0.03, p = .001) and Grade 12 (IRR = 1.07, b = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p = .003). As race moderated two paths from parenting to the mediators, we thus found six moderated mediation effects, which are summarized in Table 5. Among European Americans only, higher mother knowledge was associated with fewer externalizing problems, which in turn was associated with fewer substance use problems in Grades 9 and 12. Among European Americans only, higher father warmth was associated with better academic achievement, which in turn was associated with fewer substance use problems in Grades 9 and 12, as well as lower odds of alcohol and marijuana dependence in Grade 12.

Table 5.

Estimates and CIs of the mediated effects for parenting models by race (n =352)

| Asian/Pacific Islander Americans |

European Americans |

|||||

| Indirect effects | Lower 95% CI | Estimate | Upper 95% CI | Lower 95% CI | Estimate | Upper 95% CI |

| Grade 7 mother knowledge | ||||||

| → Grade 8 EXT → Grade 9 substance use problems Grade 7 mother knowledge | -.209 | .001 | .206 | -.626 | -.314 | -.081 |

| Grade 7 mother knowledge | ||||||

| → Grade 8 EXT → Grade 12 substance use problems | -.137 | .002 | .147 | -.429 | -.210 | -.049 |

| Grade 7 father warmth | ||||||

| → Grade 8 GPA → Grade 9 substance use problems | -.227 | -.023 | .189 | -.899 | -.459 | -.130 |

| Grade 7 father warmth | ||||||

| → Grade 8 GPA → Grade 12 substance use problems | -.283 | -.076 | .081 | -.529 | -.259 | -.062 |

| Grade 7 father warmth | ||||||

| → Grade 8 GPA → Grade 12 alcohol dependence | -.320 | -.082 | .095 | -.659 | -.292 | -.036 |

| Grade 7 father warmth | ||||||

| → Grade 8 GPA → Grade 12 marijuana dependence | -.236 | -.058 | .073 | -.45 | -.201 | -.009 |

Notes: The effects of baseline academic achievement, baseline externalizing problems, baseline substance use behaviors and significant baseline covariates, were controlled for. Asymmetric confidence intervals were obtained from RMediation utilizing the product of coefficients method. CI = confidence interval; EXT = externalizing problems; GPA = grade point average (academic achievement). Significant mediation effects are in bold.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, the direct effect of father knowledge on substance use problems in Grade 9 was significant for both European and API Americans. Contrary to our hypothesis, the direct effect of mother psychological control on substance use problems in Grade 9 was not moderated by race. Our findings may have differed from those reported by Luk et al. (2015) because parental knowledge was not examined in their study and a different set of parental control questionnaire items was used. Parenting effects on substance use may also be more salient during the adolescent period compared with the college years because college drinking behaviors are primarily shaped by peers and the college environment (Simons-Morton et al., 2016). Importantly, our findings do not preclude the possibility that psychological control may have differential associations with substance use variables across different API subgroups, which could be masked in the current study.

The two sets of significant parenting main effects were in line with existing theory. Conceptually, mother psychological control may be considered part of authoritarian parenting in which demands and strictness are paired with little emotional support. Thus, in contrast to studies suggesting that authoritarian parenting might be beneficial for API American youth for other outcomes (Ang, 2006; Leung et al., 1998; Li et al., 2010), parental control may actually confer risk when it comes to the prediction of substance use problems. One possible explanation is that mother psychological control increases the novelty of time-limited substance use experimentation, and so for both European American and API American adolescents, it was associated with increased substance use problems in Grade 9 but neither substance use problems in Grade 12 nor other forms of substance use dependence in Grade 12.

Father knowledge was a consistent protective factor against four substance use outcomes. Extending prior research showing parental knowledge as a protective factor against adolescent substance use (Lippold et al., 2013), our findings highlight the importance of father parenting involvement specifically. Hypothetically, parental knowledge reflects the overall quality of the parent-adolescent relationship, because parents typically acquire knowledge about adolescents’ whereabouts based on the adolescents’ willingness to disclose information (Racz & McMahon, 2011). Thus, cultivation of the father–adolescent relationship as a secure environment for adolescents to talk about where they go, with whom they hang out, and what daily challenges they encounter may be important for substance use prevention.

Parenting dimensions that had significant indirect effects on substance use (mother knowledge and father warmth) were different from those that exerted direct effects on substance use (mother psychological control and father knowledge). For European but not API Americans, mother knowledge in Grade 7 predicted fewer substance use problems in Grades 9 and 12 through fewer externalizing problems in Grade 8. The mediating role of externalizing problems has been implicated in previous research (Goodman, 2010; Monshouwer et al., 2012) and is consistent with substance use etiology models (Sher, 1991; Sitnick et al., 2014). Similarly, for European Americans only, father warmth in Grade 7 predicted fewer alcohol problems in Grade 9, alcohol problems, alcohol dependence, and marijuana dependence in Grade 12 through better academic achievement in Grade 8. Parental warmth may be associated with better academic achievement through greater perceptions of control (Fulton & Turner, 2008) or improved self-efficacy (Boon, 2007). Overall, externalizing problems and academic achievement, respectively, may explain the prospective effects of mother knowledge and father warmth on problematic substance use among European Americans, and these mediational pathways were not generalizable to API Americans as an aggregate group.

Among Asian American youth, acculturation and low parental respect were indirectly associated with substance use risk through mediators such as peer substance use, alcohol resistance self-efficacy, and alcohol expectancies (Shih et al., 2012; Thai et al., 2010). The absence of meditation effects among API Americans in this study may reflect that parental warmth, psychological control, and knowledge are not the most salient distal predictors of substance use risk among API American youth. Culturally specific risk and protective factors (e.g., acculturation and parental respect) may be more salient initiators of pathways to substance use risk among API American youth.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size for the API group was relatively small in the context of a complex moderated mediation model. The relatively small API group was also heterogeneous, with adolescents coming from various ethnic subgroup backgrounds. As such, despite notable differences in substance use risks by ethnic subgroup, nativity, and generational status (Hendershot et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2013), our study was limited as further ethnic subgroup analyses were not feasible. Second, although attrition in mediators and substance use outcomes did not differ by age, gender, and baseline substance use, missing data in externalizing problems differed by race and could have biased our findings. Third, this study did not include measures of acculturation, which could be a significant covariate or moderator (Hahm et al., 2003; Luk et al., 2013). Fourth, the participation rate of 64.6% could have biased the representativeness of the study sample. Fifth, in the context of using negative binomial regression models and implementing multiple imputation procedures, we did not directly contrast the indirect effects using a multiple-group analysis approach, nor could we test whether the variances were equal across groups. Given the complexity (and difficulty) of integrating multiple imputation, negative binomial models with multiple-group analyses, we feel that our approach strikes the best balance between an ideal and feasible analytic approach. Last, African Americans were excluded because measurement invariance of parenting was not yet established for African Americans. This literature gap should be addressed in future research.

Important clinical implications can be drawn from this study. First, we found no evidence that parental control may have beneficial effects among API youth as it pertains to substance use prevention. Clinicians working with API parents who justify their relatively controlling parenting practices based on cultural background could use the current findings as a point of discussion and highlight that evidence to date does not support psychological control as an effective substance use intervention approach for API adolescents. Second, although we may not fully understand the mechanisms by which parental knowledge confers protection against substance use behaviors among API youth, interventions promoting parents’ understanding of the daily activities and whereabouts of API youth will likely be beneficial to most API youth, particularly when fathers are involved. Finally, we replicated Luk et al. (2015) and found that parental warmth was unrelated to substance use behaviors among API youth, suggesting that the direct expression of affection may not be a crucial substance use treatment target. Future research should identify culturally specific developmental pathways through which parenting may lead to substance use behaviors among different subgroups of API American youth.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a National Research Service Award from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31AA020700), grants awarded for the Developmental Pathways Project (R01 MH/DA63711, R01 MH079402, and R01 AA018701), and the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. An earlier version of this study was presented at the 2013 Asian American Psychological Association Convention, Honolulu, HI.

References

- Achenbach T. M. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T. M., Rescorla L. A. Burlington, VT: University ofVermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. [Google Scholar]

- Ang R. P. Effects of parenting style on personal and social variables for Asian adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:503–511. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.503. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T., Muthén B. Multiple imputation with Mplus. 2010 Retrieved from http://ww.statmodel2.com/download/Imputations7.pdf.

- Atkins D. C., Baldwin S. A., Zheng C., Gallop R. J., Neighbors C. A tutorial on count regression and zero-altered count models for longitudinal substance use data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:166–177. doi: 10.1037/a0029508. doi:10.1037/a0029508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber B. K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development. 1996;67:3296–3319. doi:10.2307/1131780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber B. K., Olsen J. A. Socialization in context: Connection, regulation, and autonomy in the family, school, and neighborhood, and with peers. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12:287–315. doi:10.1177/0743554897122008. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G. M., Reifman A. S., Farrell M. P., Dintcheff B. A. The effects of parenting on the development of adolescent alcohol misuse: A six-wave latent growth model. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:175–186. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00175.x. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance abuse. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:56–95. doi:10.1177/0272431691111004. [Google Scholar]

- Boon H. Low and high-achieving Australian secondary school students: Their parenting, motivations and academic achievement. Australian Psychologist. 2007;42:212–225. doi:10.1080/00050060701405584. [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. B., Mounts N., Lamborn S. D., Steinberg L. Parenting practices and peer group affiliation in adolescence. Child Development. 1993;64:467–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02922.x. doi:10.2307/1131263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao R., Tseng V. Parenting of Asians. In: Bornstein M. H., editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 4: Social conditions and applied parenting (2nd ed., pp. 59–93) Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chao R. K. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development. 1994;65:1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. doi:10.2307/1131308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao R. K. Extending research on the consequences of parenting style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Development. 2001;72:1832–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00381. doi:10.1111/1467–8624.00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao R. K., Aque C. Interpretations of parental control by Asian immigrant and European American youth. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:342–354. doi: 10.1037/a0015828. doi:10.1037/a0015828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. Diversity within: Subgroup differences of youth problem behaviors among Asian Pacific Islander American adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:352–370. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20196. doi:10.1002/jcop.20196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle A., Ostrander R., Skare S., Crosby R. D., August G. J. Convergent and criterion-related validity of the Behavior Assessment System for Children-Parent Rating Scale. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26:276–284. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_6. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. R., Lambert L. S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:1–22. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton E., Turner L. A. Students’ academic motivation: Relations with parental warmth, autonomy granting, and supervision. Educational Psychology. 2008;28:521–534. doi:10.1080/01443410701846119. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. Substance use and common child mental health problems: Examining longitudinal associations in a British sample. Addiction. 2010;105:1484–1496. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02981.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Dawson D. A., Stinson F. S., Chou S. P., Dufour M. C., Pickering R. P. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug andAlcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm H. C., Lahiff M., Guterman N. B. Acculturation and parental attachment in Asian-American adolescents’ alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00058-2. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller M., Handley E., Chassin L., Bountress K. Developmental cascades: Linking adolescent substance use, affiliation with substance use promoting peers, and academic achievement to adult substance use disorders. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:899–916. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000532. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman J. D., Patock-Peckham J. A., Corbin W. R., Gates J. R., Leeman R. F., Luk J. W., King K. M. Direct and indirect links between parenting styles, self-concealment (secrets), impaired control over drinking and alcohol-related outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;40:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.08.009. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot C. S., Dillworth T. M., Neighbors C., George W.H. Differential effects of acculturation on drinking behavior in Chinese and Korean-American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol andDrugs. 2008;69:121–128. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.121. doi:10.15288/jsad.2008.69.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J. S., Huang H., Sabri B., Kim J. S. Substance abuse among Asian American youth: An ecological review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:669–677. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.11.015. [Google Scholar]

- Hudziak J. J., Copeland W., Stanger C., Wadsworth M. Screening for DSM-IV externalizing disorders with the Child Behavior Checklist: A receiver-operating characteristic analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2004;45:1299–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00314.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura K. Y., Frost R. O., Harmatz M. G. The relationship of perceived parenting styles to perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32:317–327. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00026-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. M., Neff J. A. Direct and indirect effects of parental influence upon adolescent alcohol use: A structural equation modeling analysis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2010;19:244–260. doi:10.1080/1067828X.2010.488963. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. T., Rose J. S., Engel-Rebitzer E., Selya A., Dierker L. Alcohol dependence symptoms among recent onset adolescent drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1160–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.014. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. K., Han B., Gfroerer J. C. Differences in the prevalence rates and correlates of alcohol use and binge alcohol use among five Asian American subpopulations. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:1816–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung K., Lau S., Lam W.-L. Parenting styles and academic achievement: A cross-cultural study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1998;44:157–172. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23093664. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Costanzo P. R., Putallaz M. Maternal socialization goals, parenting styles, and social-emotional adjustment among Chinese and European American young adults: Testing a mediation model. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2010;171:330–362. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2010.505969. doi:10.1080/00221325.2010.505969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold M. A., Greenberg M. T., Collins L. M. Parental knowledge and youth risky behavior: A person oriented approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:1732–1744. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9893-1. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9893-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas C. P. The use of structured diagnostic interviews in clinical child psychiatric practice. In: First M. B., editor. Standardized evaluation in clinical practice (Vol. 22, pp. 75–102) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luk J. W., Emery R. L., Karyadi K. A., Patock-Peckham J. A., King K. M. Religiosity and substance use among Asian American college students: Moderated effects of race and acculturation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;130:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.023. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk J. W., Farhat T., Iannotti R. J., Simons-Morton B. G. Parent-child communication and substance use among adolescents: Do father and mother communication play a different role for sons and daughters? Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.009. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk J. W., King K. M., McCarty C. A., Stoep A. V, McCauley E. Measurement invariance testing of a three-factor model of parental warmth, psychological control, and knowledge across European and Asian/Pacific Islander American youth. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2016;7:97–107. doi: 10.1037/aap0000040. doi:10.1037/aap0000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk J. W., Patock-Peckham J. A., King K. M. Are dimensions of parenting differentially linked to substance use across Caucasian and Asian American college students? Substance Use & Misuse. 2015;50:1360–1369. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1013134. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.1013134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Lockwood C. M., Hoffman J. M., West S. G., Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E. T., Neal D. J., Roberts L. J., Baer J. S., Cressler S. O., Metrik J., Marlatt G. A. Test-retest reliability of alcohol measures: Is there a difference between internet-based assessment and traditional methods? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:56–63. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.16.1.56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monshouwer K., Harakeh Z., Lugtig P., Huizink A., Creemers H. E., Reijneveld S. A., Vollebergh W. A. M. Predicting transitions in low and high levels of risk behavior from early to middle adolescence: The TRAILS study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:923–931. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9624-9. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9624-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998-2014. Mplus user’s guide, seventh edition. [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus K., Rudasill K. M., Rakes C. R. A longitudinal study of school connectedness and academic outcomes across sixth grade. Journal of School Psychology. 2012;50:443–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2012.03.002. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham J. A., Morgan-Lopez A. A. College drinking behaviors: Mediational links between parenting styles, impulse control, and alcohol-related outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:117–125. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.117. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Washington, D.C.: Author; 2013. The rise of Asian Americans. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2013/04/Asian-Americans-new-full-report-04–2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Price R. K., Risk N. K., Wong M. M., Klingle R. S. Substance use and abuse by Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: Preliminary results from four national epidemiologic studies. Public Health Reports, 117, Supplement. 2002;1:S39–S50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach A., Epstein N., Riley P., Falconier M., Fang X. Effects of parental warmth and academic pressure on anxiety and depression symptoms in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24:106–116. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9818-y. [Google Scholar]

- Racz S. J., McMahon R. J. The relationship between parental knowledge and monitoring and child and adolescent conduct problems: A 10-year update. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:377–398. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0099-y. doi:10.1007/s10567-011-0099-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer E. S. Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–424. doi:10.2307/1126465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. L., Graham J. W. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher K. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press; 1991. Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. [Google Scholar]

- Shih R. A., Miles J. N., Tucker J. S., Zhou A. J., D’Amico E. J. Racial/ethnic differences in the influence of cultural values, alcohol resistance self-efficacy, and alcohol expectancies on risk for alcohol initiation. Psychology ofAddictive Behaviors. 2012;26:460–470. doi: 10.1037/a0029254. doi:10.1037/a0029254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B., Haynie D., Liu D., Chaurasia A., Li K., Hingson R. The effect of residence, school status, work status, and social influence on the prevalence of alcohol use among emerging adults. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77:121–132. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.121. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitnick S. L., Shaw D. S., Hyde L. W. Precursors of adolescent substance use from early childhood and early adolescence: Testing a developmental cascade model. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26:125–140. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000539. doi:10.1017/S0954579413000539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit E., Verdurmen J., Monshouwer K., Smit F. Family interventions and their effect on adolescent alcohol use in general populations; a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.032. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So D. W., Wong F. Y. Alcohol, drugs, and substance use among Asian-American college students. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38:35–42. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2006.10399826. doi:10.1080/02791072.2006.10399826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R. L., Redmond C., Shin C. Randomized trial of brief family interventions for general populations: Adolescent substance use outcomes 4 years following baseline. Journal ofConsulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:627–642. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.627. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary ofNational Findings. 2014 NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863. Rockville, MD: Author. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai N. D., Connell C. M., Tebes J. K. Substance use among Asian American adolescents: Influence of race, ethnicity, and acculturation in the context of key risk and protective factors. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2010;1:261–274. doi: 10.1037/a0021703. doi:10.1037/a0021703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D., MacKinnon D. P. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. doi:10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Kviz F. J., Miller A. M. The mediating role of parent child bonding to prevent adolescent alcohol abuse among Asian American families. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2012;14:831–840. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9593-7. doi:10.1007/s10903-012-9593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H. R., Labouvie E. W. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. doi:10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Okuda M., Hser Y. I., Hasin D., Liu S. M., Grant B. F., Blanco C. Twelve-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders and treatment-seeking among Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.12.009. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]