Abstract

Objective:

The UPPS-P model posits that impulsivity comprises five factors: positive urgency, negative urgency, lack of planning, lack of perseverance, and sensation seeking. Negative and positive urgency are the traits most consistently associated with alcohol problems. However, previous work has examined alcohol problems either individually or in the aggregate, rather than examining multiple problem domains simultaneously. Recent work has also questioned the utility of distinguishing between positive and negative urgency, as this distinction did not meaningfully differ in predicting domains of psychopathology. The aims of this study were to address these issues by (a) testing unique associations of UPPS-P with specific domains of alcohol problems and (b) determining the utility of distinguishing between positive and negative urgency as risk factors for specific alcohol problems.

Method:

Associations between UPPS-P traits and alcohol problem domains were examined in two cross-sectional data sets using negative binomial regression models.

Results:

In both samples, negative urgency was associated with social/interpersonal, self-perception, risky behaviors, and blackout drinking problems. Positive urgency was associated with academic/occupational and physiological dependence problems. Both urgency traits were associated with impaired control and self-care problems. Associations for other UPPS-P traits did not replicate across samples.

Conclusions:

Results indicate that negative and positive urgency have differential associations with alcohol problem domains. Results also suggest a distinction between the type of alcohol problems associated with these traits—negative urgency was associated with problems experienced during a drinking episode, whereas positive urgency was associated with alcohol problems that result from longer-term drinking trends.

Extensive research has established that impulsivity plays a major role in alcohol use and its associated problems (Coskunpinar et al., 2013; Dick et al., 2010; Lejuez et al., 2010). Impulsivity is a multidimensional construct that encompasses distinct, but related, traits that lead to rash action (for a review, see Birkley & Smith, 2011). Specific impulsivity traits have been shown to contribute to different aspects of alcohol involvement (Magid & Colder, 2007; Settles et al., 2012; Shin et al., 2012; Stautz & Cooper, 2013). However, these studies aggregate different alcohol problems (e.g., social/interpersonal problems, impaired control) into a single variable. The present study examined how different impulsivity traits relate to specific consequences of alcohol use.

Impulsivity is characterized by a tendency to act without planning and a diminished ability to persevere in tasks, delay gratification, and regulate emotion (Lejuez et al., 2010). This construct exists on a continuum, with lower levels of impulsivity serving a function in normative behavior and higher levels associated with several psychological disorders, including substance use disorders (Links et al., 1999; Sher & Trull, 1994; Winstanley et al., 2006). Numerous measures have been developed to measure specific impulsivity facets. For instance, the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire control scale measures lack of planning, and Eysenck’s venturesomeness scale measures sensation seeking (Dick et al., 2010).

Other models of impulsivity are designed to capture multiple facets of impulsivity within a single measure. One such model, the UPPS model, suggests that impulsivity comprises (a) negative urgency, or the tendency to act rashly when in a negative mood; (b) lack of perseverance, or a tendency to not finish tasks; (c) lack of planning, or a tendency to act without thinking; and (d) sensation seeking, a tendency to try new, exciting behaviors or activities (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Later iterations (UPPS-P) added positive urgency, or the tendency to act rashly when in a positive mood (Cyders & Smith, 2008). The UPPS-P model has a number of advantages: It was developed by empirically organizing existing measures of impulsivity, fits well with prominent models of personality, and distinguishes between the different processes that may lead to impulsive action (i.e., emotion based, sensation seeking, conscientiousness based; Dick et al., 2010).

An additional advantage of the UPPS-P model is that its various facets have been found to predict distinct externalizing and substance-related behaviors. For externalizing behaviors, negative urgency exhibits the strongest and most consistent association. The behaviors associated with negative urgency include bulimia nervosa, aggression, risky sex, illegal drug use, tobacco craving, binge eating, and problem gambling (Anestis et al., 2007; Billieux et al., 2010; Birthrong & Latzman, 2014; Pearson et al., 2015; Scott et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2007). Positive urgency is associated with similar behaviors, including pathological gambling, risky sexual behavior, nicotine dependence, and illegal drug use (Cyders & Smith, 2008; Spillane et al., 2010; Zapolski et al., 2009). There is substantially less research linking the other UPPS-P traits to externalizing behaviors. However, there is some evidence that sensation seeking is associated with the frequency of engagement in risk-taking behaviors (Derefinko et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2007). Sensation seeking may also be useful for differentiating those who use substances from those who do not (Spillane et al., 2010).

A similar pattern is observed for associations between UPPS-P traits and alcohol-related behaviors, with both urgency traits exhibiting consistent associations with excessive alcohol use (e.g., binge drinking, heavy episodic drinking) and problems from use. Negative urgency has been found to be associated with alcohol-related risk-taking behaviors, including drinking and driving, alcohol-related negative consequences, and alcohol dependence (Coskunpinar et al., 2013; Settles et al., 2012; Treloar et al., 2012). Similarly, positive urgency has been found to be associated with alcohol-related negative consequences and to prospectively predict an increased quantity of alcohol consumed in college-aged samples (Cyders et al., 2009; LaBrie et al., 2014). Sensation seeking has been shown to predict frequency of use among adolescent and college samples (Cyders et al., 2009; MacPherson et al., 2010). There is less evidence supporting the association of lack of planning and lack of perseverance with alcohol-related behaviors. Some research suggests that lack of perseverance is related to the quantity of alcohol consumed, whereas lack of planning may be associated with alcohol dependence and general alcohol misuse (Coskunpinar et al., 2013; MacKillop et al., 2007).

Despite this body of research, it remains unclear whether the UPPS-P traits are differentially associated with specific domains of alcohol-related negative consequences. Previous studies have often treated alcohol-related negative consequences as a single variable, rather than examining multiple problem domains separately, or examined specific alcohol-related behaviors (e.g., driving after drinking). The current study tested the relationship of the five UPPS-P impulsivity traits with eight domains of drinking consequences assessed by the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read et al., 2006). These associations were tested across two samples of college students, and only results that replicated across both samples were interpreted.

An additional goal of the current study was to test the utility of the distinction between negative and positive urgency. A recent meta-analytic review raised questions about this distinction, finding no difference in the prediction of impulsivity-related forms of psychopathology by the two types of urgency (Berg et al., 2015). We hypothesized that the distinction between positive and negative urgency is more important in predicting specific behaviors, in this case alcohol-related problem domains, than at higher levels of aggregation, such as broad domains of psychopathology (Smith et al., 2009). Based on previous findings for alcohol-related negative consequences in general, we anticipated that positive urgency and negative urgency would be more consistently associated with YAACQ domains than other UPPS-P traits, but we did not advance specific hypotheses about the differences in associations for positive and negative urgency.

Method

Participants

Study procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board. Data from Sample 1 were collected in the laboratory as part of a study investigating the role of decision making in alcohol-related behaviors. Data from Sample 2 were collected as part of an online study investigating a novel form of the Alcohol Purchase Task (Murphy & MacKillop, 2006). These samples were selected because they (a) involved college students, (b) were collected during similar time frames, and (c) were designed to answer similar questions. Participants were granted academic credit following study completion. Informed consent was obtained before beginning study sessions.

Participants were students enrolled in introductory psychology classes at a large midwestern university who were 18 years old or older and fluent in written and spoken English. Sample 1 consisted of 348 students between 18 and 25 years old (M = 18.8 years, SD = 0.96). A little more than half of these students were female (59.8%), and the majority were White (76%), with 14% Black/African American and 6% Asian. Sample 2 consisted of 471 students between 18 and 24 years old (M = 18.5 years old, SD = 0.96). A little more than half of these students were male (56.0%), and the majority were White (81%), with 8% Black and 6% Asian. These were convenience samples that included mostly college freshmen (79.5%) or sophomores (14.0%) and those younger than age 21 years (95.3%). The samples did not significantly differ on any demographic variable.

Measures

Demographics.

Demographic information (e.g., age, sex) was collected with a self-report questionnaire.

Binge drinking.

Binge drinking was assessed with the question, “During the past month, how many times did you have 4/5 (women/men) or more drinks of alcohol at one time?”

Impulsivity traits.

The UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS-P; Lynam et al., 2007) was used to assess impulsivity traits. This 59-item questionnaire measures negative urgency, lack of perseverance, lack of planning, sensation seeking, and positive urgency. Participants responded using a four-point Likert scale (agree strongly to disagree strongly). Each subscale was calculated by taking the mean of all items assigned to each scale. The internal consistency reliabilities (Sample 1/Sample 2 in parentheses) in the present samples were as follows: negative urgency (0.86/0.87), positive urgency (0.93/0.93), (lack of) planning (0.88/0.87), (lack of) perseverance (0.85/0.81), and sensation seeking (0.82/0.82).

Alcohol-related consequences.

The YAACQ (Read et al., 2006) was used to assess consequences and problems experienced over the past year as a result of consuming alcohol. Participants responded to 48 items with “yes” or “no,” indicating whether they had experienced each consequence. This questionnaire has eight subscales (internal consistency reliabilities for Samples 1/2 in parentheses): social/interpersonal (0.75/0.73), impaired control (0.77/0.71), self-perception (0.84/0.75), self-care (0.83/0.82), risky behaviors (0.75/0.76), academic/occupational (0.75/0.74), physiological dependence (0.54/0.58), and blackout drinking (0.87/0.86).

Statistical analysis

Generalized linear negative binomial models were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The negative binomial distribution was selected to appropriately model count data. All UPPS-P subscales were included as independent variables in all analyses. Binge drinking frequency and biological sex were included as covariates, as prior studies suggest that these variables are associated with drinking consequences. Separate models were analyzed for each YAACQ subscale. Data from six participants (one from Sample 1, five from Sample 2) were excluded from analyses because of missing data. The resulting sample sizes were 347 for Sample 1 and 466 for Sample 2.

Results

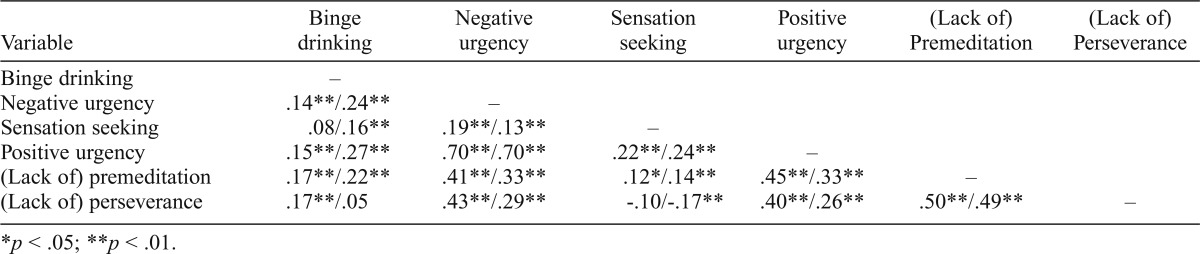

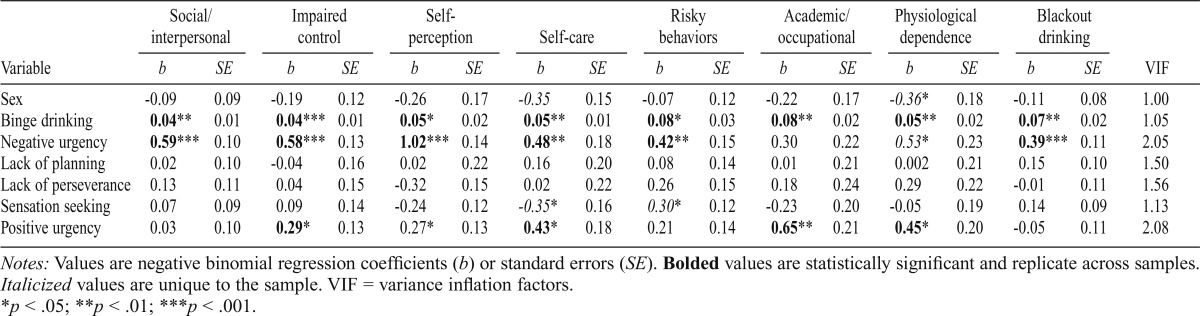

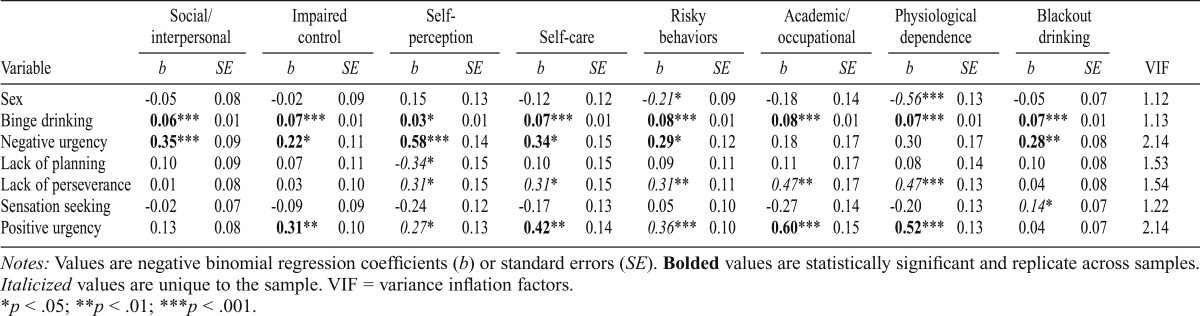

Intercorrelations among UPPS-P subscales are presented in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results of analyses evaluating the association of separate impulsivity traits with specific alcohol problems for Sample 1 and Sample 2. A number of associations were consistent across both samples. Binge drinking frequency was significantly associated with all types of alcohol problems, such that greater frequency of binge drinking was associated with experiencing more alcohol problems. Negative urgency was significantly and positively associated across both samples with social/interpersonal, self-perception, risky behaviors, and blackout drinking problems. Positive urgency was significantly and positively associated with academic/occupational and physiological dependence problems. Both positive and negative urgency were significantly and positively associated with impaired control and self-care problems. The associations that differed across samples can be viewed in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Correlations among predictors for Sample 1/Sample 2

| Variable | Binge drinking | Negative urgency | Sensation seeking | Positive urgency | (Lack of) Premeditation | (Lack of) Perseverance |

| Binge drinking | – | |||||

| Negative urgency | .14**/.24** | – | ||||

| Sensation seeking | .08/.16** | .19**/13** | – | |||

| Positive urgency | .15**/27** | .70**/.70** | .22**/.24** | – | ||

| (Lack of) premeditation | .17**/22** | .41**/.33** | .12*/.14** | .45**/.33** | – | |

| (Lack of) perseverance | .17**/.05 | .43**/.29** | -.10/-.17** | .40**/.26** | .50**/.49** | – |

p < .05;

p < .01.

Table 2.

Associations of UPPS-P traits with alcohol problems for Sample 1

| Variable | Social/interpersonal |

Impaired control |

Self-perception |

Self-care |

Risky behaviors |

Academic/occupational |

Physiological dependence |

Blackout drinking |

|||||||||

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | VIF | |

| Sex | -0.09 | 0.09 | -0.19 | 0.12 | -0.26 | 0.17 | -0.35 | 0.15 | -0.07 | 0.12 | -0.22 | 0.17 | -0.36* | 0.18 | -0.11 | 0.08 | 1.00 |

| Binge drinking | 0.04** | 0.01 | 0.04*** | 0.01 | 0.05* | 0.02 | 0.05** | 0.01 | 0.08* | 0.03 | 0.08** | 0.02 | 0.05** | 0.02 | 0.07** | 0.02 | 1.05 |

| Negative urgency | 0.59*** | 0.10 | 0.58*** | 0.13 | 1.02*** | 0.14 | 0.48** | 0.18 | 0.42** | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.53* | 0.23 | 0.39*** | 0.11 | 2.05 |

| Lack of planning | 0.02 | 0.10 | -0.04 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.002 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 1.50 |

| Lack of perseverance | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.15 | -0.32 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.22 | -0.01 | 0.11 | 1.56 |

| Sensation seeking | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.14 | -0.24 | 0.12 | -0.35* | 0.16 | 0.30* | 0.12 | -0.23 | 0.20 | -0.05 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 1.13 |

| Positive urgency | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.29* | 0.13 | 0.27* | 0.13 | 0.43* | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.65** | 0.21 | 0.45* | 0.20 | -0.05 | 0.11 | 2.08 |

Notes: Values are negative binomial regression coefficients (b) or standard errors (SE). Bolded values are statistically significant and replicate across samples. Italicized values are unique to the sample. VIF = variance inflation factors.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Table 3.

Associations of UPPS-P traits with alcohol problems for Sample 2

| Variable | Social/interpersonal | Impaired control |

Self-perception |

Self-care |

Risky behaviors |

Academic/occupational |

Physiological dependence |

Blackout drinking |

|||||||||

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | VIF | |

| Sex | -0.05 | 0.08 | -0.02 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.13 | -0.12 | 0.12 | -0 21* | 0.09 | -0.18 | 0.14 | -0.56*** | 0.13 | -0.05 | 0.07 | 1.12 |

| Binge drinking | 0.06*** | 0.01 | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 0.08*** | 0.01 | 0.08*** | 0.01 | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 1.13 |

| Negative urgency | 0.35*** | 0.09 | 0.22* | 0.11 | 0.58*** | 0.14 | 0.34* | 0.15 | 0.29* | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.28** | 0.08 | 2.14 |

| Lack of planning | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.11 | -034* | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 1.53 |

| Lack of perseverance | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 031* | 0.15 | 0.31* | 0.15 | 0.31** | 0.11 | 0.47** | 0.17 | 0.47*** | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 1.54 |

| Sensation seeking | -0.02 | 0.07 | -0.09 | 0.09 | -0.24 | 0.12 | -0.17 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.10 | -0.27 | 0.14 | -0.20 | 0.13 | 0.14* | 0.07 | 1.22 |

| Positive urgency | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.31** | 0.10 | 0.27* | 0.13 | 0.42** | 0.14 | 0.36*** | 0.10 | 0.60*** | 0.15 | 0.52*** | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 2.14 |

Notes: Values are negative binomial regression coefficients (b) or standard errors (SE). Bolded values are statistically significant and replicate across samples. Italicized values are unique to the sample. VIF = variance inflation factors.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Discussion

These results provide initial evidence that facets of the UPPS-P have differential associations with specific domains of alcohol problems. Consistent with previous research and hypotheses, negative and positive urgency had the most consistent association with alcohol problems and were the only impulsivity traits with replicated associations across both samples. Negative urgency was associated with social/interpersonal, self-perception, risky behaviors, and blackout drinking problems, whereas positive urgency was associated with academic/occupational and physiological dependence problems. Both urgency traits were associated with impaired control and self-care problems. These results provide evidence for the utility of the distinction between positive and negative urgency when studying specific alcohol problems.

Urgency traits

Negative urgency has been found to be particularly important for externalizing dysfunction (Settles et al., 2012) and is related to low distress tolerance and externalizing dysfunction resulting from emotional distress (Pearson et al., 2015; Settles et al., 2012). In this study, negative urgency was associated with social/interpersonal, self-perception, risky behaviors, and blackout drinking. Each of these domains reflects consequences experienced during a drinking episode. Our results suggest that individuals high in negative urgency might subjectively experience negative affect during the drinking episode, resulting in impulsive action and immediate negative consequences.

In contrast, positive urgency was associated with longerterm or persistent alcohol problems and with consequences extending beyond the drinking episode: academic/occupational and physiological dependence problems, including symptoms of alcohol use disorder (e.g., withdrawal, role interference). Consistent with this finding, previous research has suggested that positive urgency differentiates substance abusers from eating disordered individuals and controls (Cyders et al., 2007). These results may indicate that individuals high in positive urgency drink to enhance positive mood and do so in a way that facilitates the development and maintenance of problematic drinking or alcohol use disorder (Cooper et al., 2000). Alternatively, the experience of positive affect for these individuals could result in increased urges to drink heavily, further contributing to these longer-term negative consequences. Similar patterns have been observed in pathological gamblers, where the experience of positive mood can result in the temptation to resume gambling behavior (Holub et al., 2005).

Both of the urgency traits were associated with impaired control and self-care problems. Although negative and positive urgency are distinct traits, both involve a tendency to engage in rash action when experiencing intense emotion (Cyders & Smith, 2007). These results suggest that the inability to control drinking and failure to properly take care of oneself because of drinking are related to impulsive action in response to strong mood, regardless of the valence.

Results of this study suggest that positive and negative urgency may be viable targets for prevention or intervention efforts among young adults experiencing alcohol problems. Interventions that target characterological traits associated with substance use (e.g., hopelessness, reward processing, anxiety sensitivity, impulsivity, sensation seeking) have been shown to be effective in reducing alcohol use (O’Leary-Barrett et al., 2016) and promoting smoking cessation (MacPherson et al., 2010) in adolescents. To date, no intervention has been designed to address the role of urgency traits in problematic alcohol use. However, intervention approaches with components focused on coping with strong emotion, such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Linehan, 1993), have been shown to reduce substance use in samples with comorbid personality and substance use disorders (Lee et al., 2015). Similar interventions incorporating emotional regulation strategies may be useful for young adults with high levels of negative urgency. In addition, interventions that focus on adaptive methods for maintaining or enhancing positive mood states may be effective in reducing alcohol problems in individuals high in positive urgency (Smith & Cyders, 2016).

Limitations

These results should be considered in the context of several limitations. These samples used primarily college freshmen enrolled in psychology classes at a midwestern university. Future research using noncollege samples is needed to replicate these associations. In addition, this study used one self-report measure of impulsivity and may not capture important aspects of this construct assessed by behavioral measures of impulsivity (Dougherty et al., 2005; Logan, 1994). Finally, data from both studies are cross-sectional, limiting inferences about covariation over time. However, as a recent review indicated no difference between positive and negative urgency in their associations with psychopathology domains (Berg et al., 2015), demonstrating a cross-sectional difference in associations between these traits and alcohol-related negative consequences is necessary before conducting prospective or intensive longitudinal (e.g., ecological momentary assessment) studies.

Conclusions and future directions

The present study contributes to our understanding of how different pathways to impulsive action might influence risk for specific alcohol-related negative consequences. The results indicated that the two urgency traits were the only impulsivity factors consistently associated with specific alcohol-related problem domains and also demonstrated the utility of distinguishing between positive and negative urgency. We found negative urgency to be associated with negative consequences experienced during the drinking episode, whereas positive urgency was associated with consequences experienced later or resulting from longer-term use.

Future research is needed to replicate this distinction and to explore mechanisms by which each of the urgency traits might influence alcohol-related negative consequences. One promising direction for such work is using in-the-moment assessment methods, such as ecological momentary assessment, to track the relationship between urgency, mood, alcohol consumption, and the experience of negative consequences (Tomko et al., 2014). Our results suggest that this within-episode pathway might be important for negative urgency and affect, but not positive urgency and affect.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01 AA019546 (to Denis M. McCarthy) and T32 AA013526 (to Kenneth J. Sher).

References

- Anestis M. D., Selby E. A., Fink E. L., Joiner T. E. The multifaceted role of distress tolerance in dysregulated eating behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:718–726. doi: 10.1002/eat.20471. doi:10.1002/eat.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J. M., Latzman R. D., Bliwise N. G., Lilienfeld S. O. Parsing the heterogeneity of impulsivity: A meta-analytic review of the behavioral implications of the UPPS for psychopathology. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27:1129–1146. doi: 10.1037/pas0000111. doi:10.1037/pas0000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., Gay P., Rochat L., Van der Linden M. (2010). The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours Behaviour Research and Therapy 481085–1096.doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkley E. L., Smith G. T. Recent advances in understanding the personality underpinnings of impulsive behavior and their role in risk for addictive behaviors. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2011;4:215–227. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104040215. doi:10.2174/1874473711104040215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birthrong A., Latzman R. D. Aspects of impulsivity are differentially associated with risky sexual behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;57:8–13. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.009. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. L., Agocha V. B., Sheldon M. S. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A., Dir A. L., Cyders M. A. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: A meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/acer.12131. doi:10.1111/acer.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Flory K., Rainer S., Smith G. T. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first-year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Smith G. T. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:839–850. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.008. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Smith G. T. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. doi:10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Smith G. T., Spillane N. S., Fischer S., Annus A. M., Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derefinko K. J., Peters J. R., Eisenlohr-Moul T. A., Walsh E. C., Adams Z. W., Lynam D. R. Relations between trait impulsivity, behavioral impulsivity, physiological arousal, and risky sexual behavior among young men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43:1149–1158. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0327-x. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0327-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick D. M., Smith G., Olausson P., Mitchell S. H., Leeman R. F., O’Malley S. S., Sher K. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction Biology. 2010;15:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty D. M., Mathias C. W., Marsh D. M., Jagar A. A. Laboratory behavioral measures of impulsivity. Behavior Research Methods. 2005;37:82–90. doi: 10.3758/bf03206401. doi:10.3758/BF03206401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holub A., Hodgins D. C., Peden N. E. Development of the temptations for gambling questionnaire: A measure of temptation in recently quit gamblers. Addiction Research and Theory. 2005;13:179–191. doi:10.1080/16066350412331314902. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie J. W., Kenney S. R., Napper L. E., Miller K. Impulsivity and alcohol-related risk among college students: Examining urgency, sensation seeking and the moderating influence of beliefs about alcohol’s role in the college experience. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.018. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N. K., Cameron J., Jenner L. A systematic review of interventions for co-occurring substance use and borderline personality disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2015;34:663–672. doi: 10.1111/dar.12267. doi:10.1111/dar.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez C. W., Magidson J. F., Mitchell S. H., Sinha R., Stevens M. C., de Wit H. Behavioral and biological indicators of impulsivity in the development of alcohol use, problems, and disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1334–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01217.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 1993. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. [Google Scholar]

- Links P. S., Heslegrave R., van Reekum R. Impulsivity: Core aspect of borderline personality disorder. Journal ofPersonality Disorders. 1999;13:1–9. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1999.13.1.1. doi:10.1521/pedi.1999.13.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan G. D. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: A users’ guide to the stop signal paradigm. In: Dagenbach D., Carr T. H., editors. Inhibitory processes in attention, memory, and language. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 189–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam D., Smith G. T., Cyders M. A., Fischer S., Whiteside S. The UPPS-P: A multidimensional measure of risk for impulsive behavior. 2007 Unpublished technical report. [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J., Mattson R. E., Anderson MacKillop E. J., Castelda B. A., Donovick P. J. Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in undergraduate hazardous drinkers and controls. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:785–788. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.785. doi:10.15288/jsad.2007.68.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L., Magidson J. F., Reynolds E. K., Kahler C. W., Lejuez C. W. Changes in sensation seeking and risk-taking propensity predict increases in alcohol use among early adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1400–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01223.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L., Tull M. T., Matusiewicz A. K., Rodman S., Strong D. R., Kahler C. W., Lejuez C. W. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation smoking cessation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:55–61. doi: 10.1037/a0017939. doi:10.1037/a0017939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Colder C. R. The UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:1927–1937. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.013. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J. G., MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:219–227. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary-Barrett M., Castellanos-Ryan N., Pihl R. O., Conrod P. J. Mechanisms of personality-targeted intervention effects on adolescent alcohol misuse, internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016;84:438–52. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000082. doi:10.1037/ccp0000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C. M., Wonderlich S. A., Smith G. T. A risk and maintenance model for bulimia nervosa: From impulsive action to compulsive behavior. Psychological Review. 2015;122:516–535. doi: 10.1037/a0039268. doi:10.1037/a0039268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J. P., Kahler C. W., Strong D. R., Colder C. R. Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. P., DiLillo D., Maldonado R. C., Watkins L. E. Negative urgency and emotion regulation strategy use: Associations with displaced aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 2015;41:502–512. doi: 10.1002/ab.21588. doi:10.1002/ab.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles R. E., Fischer S., Cyders M. A., Combs J. L., Gunn R. L., Smith G. T. Negative urgency: A personality predictor of externalizing behavior characterized by neuroticism, low conscientiousness, and disagreeableness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:160–172. doi: 10.1037/a0024948. doi:10.1037/a0024948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher K. J., Trull T. J. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: Alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. H., Hong H. G., Jeon S. M. Personality and alcohol use: The role of impulsivity. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.006. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. T., Cyders M. A. Integrating affect and impulsivity: The role of positive and negative urgency in substance use risk. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 163, Supplement. 2016;1:S3–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.038. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. T., Fischer S., Cyders M. A., Annus A. M., Spillane N. 5., & McCarthy, D. M. On the validity and utility of dis-criminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14:155–170. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. doi:10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. T., McCarthy D. M., Zapolski T. C. B. On the value of homogeneous constructs for construct validation, theory testing, and the description of psychopathology. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:272–284. doi: 10.1037/a0016699. doi:10.1037/a0016699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane N. S., Smith G. T., Kahler C. W. Impulsivity-like traits and smoking behavior in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.008. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K., Cooper A. Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:574–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.003. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomko R. L., Solhan M. B., Carpenter R. W., Brown W. C. Jahng, 5., Wood, P. K., & Trull, T. J. Measuring impulsivity in daily life: The momentary impulsivity scale. Psychological Assessment. 2014;26:339–349. doi: 10.1037/a0035083. doi:10.1037/a0035083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar H. R., Morris D. H., Pedersen S. L., McCarthy D. M. Direct and indirect effects of impulsivity traits on drinking and driving in young adults. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:794–803. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.794. doi:10.15288/jsad.2012.73.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside S. P., Lynam D. R. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley C. A., Eagle D. M., Robbins T. W. Behavioral models of impulsivity in relation to ADHD: Translation between clinical and preclinical studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:379–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski T. C. B., Cyders M. A., Smith G. T. Positive urgency predicts illegal drug use and risky sexual behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:348–354. doi: 10.1037/a0014684. doi:10.1037/a0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]