We thank Nery et al for their insightful letter to our article.1 We alluded to the age and survival interaction with implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) use in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM) patients noted in DANISH trial in our article.1 We agree that similar trends have been observed in other trials.2 However, only four out of six trials included in our meta-analysis (DEFINITE, COMPANION, SCD-HEFT, DANISH)1 reported age stratified outcomes. Two of the four trials, SCD-HEFT3, and COMPANION4 had these outcomes reported for both ischemic and non-ischemic patients, making age stratified analysis in NICM patients difficult in absence of individual patient level data. Nonetheless, we do agree that this should be recognized as one of the key limitations of the currently available data we have from the randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In addition, all treatment decisions for ICD placement should be personalized and involve shared decision making with patients.

We agree with Barakat et al that the COMPANION4 trial did not directly report individual comparison of ICD plus cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT-D) vs. CRT-pacemaker (CRT-P). Unfortunately, our efforts to obtain the relevant information from the trial authors4 were unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the trial4 reported treatment effects of (i) CRT-D vs. pharmacotherapy [Hazard Ratio (HR) 0.50; 95% Confidence interval (CI), 0.29–0.88] and (ii) CRT-P vs. pharmacotherapy [HR; 0.91 (95% CI, 0.55–1.49)]; indicating that treatment effect of CRT-P and pharmacotherapy is relatively similar in patients with NICM.4 For further confirmation, we estimated “indirect” treatment effect using Bucher method5 of CRT-D vs. CRT-P from these estimates. We found that the “indirect” HR was 0.55 (95% CI, 0.26–1.16) which was similar to treatment effect of COMPANION trial that we used in our primary and sub-group analysis [HR; 0.50 (95% CI, 0.29–0.88)].1 Further analysis after inclusion of these indirect estimates did not affect our primary or sub-group summary estimates [summary HR reported in primary analysis using COMPANION4 trial HR; 0.77 (95% CI, 0.64–0.91), whereas summary HR using “indirect” HR for COMPANION4 trial was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.66–0.93). Similarly, summary HR reported in our sub-group analysis; 0.70 (95% CI, 0.39–1.26), which was once again equivalent to summary HR using “indirect” HR for COMPANION4 trial; 0.79 (95% CI, 0.51–1.23).

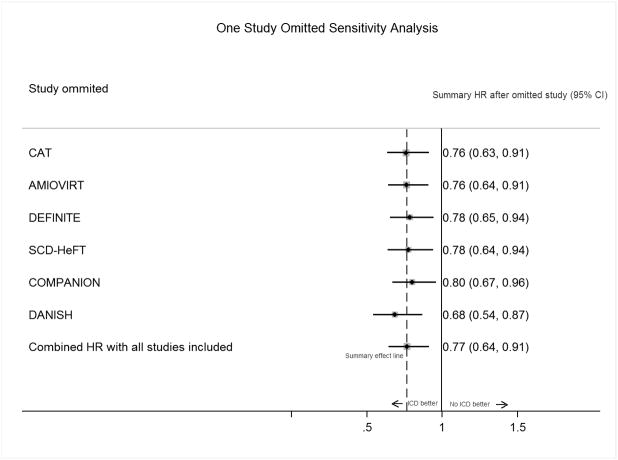

Barakat et al also suggested that since CRT improves mortality independent of ICD, inclusion of COMPANION trial, which included patients with both ICD and CRT, could be misleading. We disagree with the authors in their viewpoint. Firstly, we presented in our article ICD only summary HR; 0.76 (95% CI, 0.62–0.94), after excluding both COMPANION and patients with CRT use in the DANISH trial which was similar to our primary analysis summary HR.1 Further, when we performed one study omitted sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of exclusion of COMPANION4 trial on our primary analysis; the summary estimate did not change significantly [COMPANION included summary HR; 0.77 (95% CI, 0.64–0.91), COMPANION excluded summary HR; 0.80 (95% CI, 0.67–0.96)] (Figure 1). Similar results were also discussed by Desai et al6 in their prior meta-analysis suggesting that overall treatment effect remains robust by inclusion of the COMPANION4 trial. Finally, optimal medical therapy for heart failure has evolved over the last decade. Control arms in the included RCTs have ranged from placebo, amiodarone, to the state of the art medical therapy with CRT use in more than half of the patients in the recently concluded DANISH trial.1 Despite the evolving comparator in control arm, given the fact that baseline characteristics were similar between treatment and control groups in all these trials, one could reason that the survival benefit in each trial was driven primarily by the ICD. Limitations of meta-analysis have been previously described.7 However, our sensitivity and heterogeneity analysis detected minimal statistical heterogeneity. The treatment effects were nearly similar in magnitude and concordant in direction across all RCTs. Hence we believe that treatment effects are accurately represented in our meta-analysis and can be used clinically while having individualized discussions with the patients about the need for ICD implantation. In an era of precision medicine, we believe that current focus to risk stratify NICM patients for sudden cardiac death solely on basis of ejection fraction falls short of perfect and future efforts should focus on improvement of risk stratification of NICM patients.

Figure 1. One Study Omitted Sensitivity Analysis to assess the effect of individual trials on summary treatment effect of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator on all-cause mortality.

Abbreviations: HR= Hazard ratio, CI= Confidence Interval; CAT= Cardiomyopathy trial; AMIOVIRT= Amiodarone vs Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Randomized Trial; DEFINITE= Defibrillator in Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation; SCD-HeFT= Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial; COMPANION= Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure; DANISH= Defibrillator Implantation in Patients with Nonischemic Systolic Heart Failure; ICD= implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Note: Black markers and solid lines around them represent summary HRs and 95% CI after excluding the study in the left column. The numerical estimates in the right column are pooled effects and 95% CI after excluding the trial in the left column from the meta-analysis. The direction and statistical significance of summary treatment effect remains similar after excluding any trial from meta-analysis indicating “robustness” of the estimated summary treatment effect.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Dr. Navkaranbir Singh Bajaj is supported by NIH grant number 5T32HL094301-07. This work was supported in part by the Walter B. Frommeyer Junior Fellowship in Investigative Medicine that was awarded to Dr. Pankaj Arora.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: None of the authors report conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Golwala H, Bajaj NS, Arora G, Arora P. Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator for Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Circulation. 2017;135:201–203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimm W. Outcomes of elderly heart failure recipients of ICD and CRT. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial I (SCD-HeFT) Investigators. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, Carson P, DiCarlo L, DeMets D, White BG, DeVries DW, Feldman AM. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140–2150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clini Epidemiol. 1997;50:683–691. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai AS, Fang JC, Maisel WH, Baughman KL. Implantable defibrillators for the prevention of mortality in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2004;292:2874–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalra R, Arora P, Morgan C, Hage FG, Iskandrian AE, Bajaj NS. Conducting and interpreting high-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12350-016-0598-9. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]