Abstract

Few empirical studies have explored the mechanisms through which racial identity, the importance of racial group membership, affects well-being for racial/ethnic minorities. Using a community sample of 161 African American adults, the present study examined whether the association between racial identity (centrality, public regard, and private regard) and life satisfaction is mediated by two identity functions, belongingness and discrimination. Our results indicated that the relationships of centrality and private regard with life satisfaction were mediated by perceptions of belongingness. Furthermore, gender moderated the strength of each of these mediating effects, such that belongingness mediated these relationships for women but not for men. Our results also indicated that the relationship between public regard and life satisfaction was mediated by perceptions of discrimination. Furthermore, higher public regard was related to lower perceptions of discrimination for women but not men. However, a combined model for public regard and life satisfaction as mediated by discrimination failed to show moderated mediation. We discuss these results in relation to research and theory on racial identity and intersectionality.

Keywords: racial identity, African Americans/blacks, sex/gender, discrimination, belongingness

Although individuals typically identify with several social groups concurrently, race is a salient and important identity that serves as a core element for many people’s sense of self (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998; Settles, 2006). Racial identity is an individual difference dimension related to the importance one places on being a member of a particular racial group (Phinney, 1990), and past research indicates that racial group membership has important implications for the physical and psychological well-being of individuals from minority racial groups (e.g., Iwamoto & Liu, 2010; Rowley, Sellers, Chavous, & Smith, 1998). However, few empirical studies have explored the mechanisms through which racial identity affects well-being. Thus, the present study examines whether the association between racial identity and life satisfaction in a community sample of African American adults is mediated by two identity functions, or perceptions about the positive and negative aspects of group membership. We posited that belongingness to one’s family and group, and perceptions of discrimination, would mediate the relationship between life satisfaction and three dimensions of racial identity and that these relationships would differ for women and men.

In this research, we use the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (Sellers et al., 1998), which suggests that an individual’s racial identity comprises three stable dimensions. Two of these dimensions are racial centrality and racial regard. Racial centrality refers to the importance of race to the self-concept. Racial regard is the evaluative dimension of identity and has two components. Private regard refers to the degree to which individuals feel positively toward their racial group and being a racial group member. Public regard refers to individuals’ perceptions of how the larger society views their racial group. These three elements are considered to be important aspects of one’s racial identity.

Research has demonstrated that racial identification is associated with several positive psychological outcomes for members of several different racial minority groups, although relationships vary by identity dimension. For racial minorities, higher racial centrality is related to higher self-esteem and quality of life and lower depression (e.g., Kiang, Yip, Gonzales-Backen, Witkow, & Fuligni, 2006; Phinney, 1990; Rowley et al., 1998; Umaña-Taylor, 2004; Utsey, Chae, Brown, & Kelly, 2002). Experimental research has also indicated that increased identification with one’s minority group membership can have positive psychological outcomes (e.g., Major, Spencer, Schmader, Wolfe, & Crocker, 1998; McKenna & Bargh, 1998). However, there are some exceptions in which racial centrality is found to be unrelated to psychological outcomes (e.g., Cross, 1991; Sellers, Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Settles, 2006; Yip & Cross, 2004).

As with racial centrality, the literature suggests more mixed patterns of relationships for public regard. Some studies have found that higher levels of public regard are related to less depression and distress (Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Settles, Navarrete, Pagano, Abdou, & Sidanius, 2010; Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2006). However, other studies have found that African Americans’ public regard was unrelated to their psychological well-being (Rowley et al., 1998; Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman, 2003; Sellers et al., 2006). Research also finds that African Americans’ positive feelings about their racial group membership (i.e., private regard) are consistently related to a number of positive psychological outcomes, including less depression, stress, and distress, and higher self-esteem (Bynum, Best, Barnes & Burton, 2008; Kiang et al., 2006; Rowley et al., 1998; Sellers et al., 2006; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Settles et al., 2010). In sum, private regard is related to positive well-being, whereas centrality and public regard are either positively related or unrelated to psychological well-being, with somewhat more literature supporting a positive association.

There are two issues that may be raised from the above literature review. First, the relationship between racial identity and psychological well-being is inconclusive for some dimensions. Second, even in the research that finds a relationship between identity and well-being, little is known about the psychological mechanisms for why racial identity and psychological well-being are related. We propose that both of these issues may be resolved through a consideration of identity functions—perceptions of the positive and negative aspects of group membership and identity enactment. Perceptions of one’s racial group as providing positive identity functions may be related to positive psychological well-being, whereas perceptions of one’s racial group as providing negative identity functions may be related to negative psychological well-being. Thus, racial identity functions may serve as mediators of the association between racial identity and well-being.

Several authors have theorized that group memberships and group identifications can serve different functions in various contexts. For example, group memberships can serve to increase self-esteem (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), reduce uncertainty (Hogg, 2006), and provide guidelines for social interactions (Deaux & Martin, 2003). Another important function that groups can serve for individuals is providing a sense of belonging and connection (e.g., Cross & Strauss, 1998), conferring both a sense of community and various forms of support. In fact, some theoretical conceptions of racial identity have identified the sense of belongingness as a core component of racial identity (e.g., Phinney, 1992; Phinney & Alipuria, 1990). Identities may also serve negative functions. For example, an awareness of prejudice and discrimination are negative experiences felt by many minority group members, including African Americans (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999). Thus, group identification may have both positive and negative functions for group members. The present study examines one positive function (belongingness) and one negative function (discrimination) as mediators of the relationship between racial identity and life satisfaction for African Americans.

Individuals who are more strongly identified with their racial group (i.e., higher centrality) or who feel more positively about their racial group (i.e., higher private regard) may seek out other group members through individual relationships and organizational involvement. Thus, group identification may provide the individual with a greater sense of belonging and acceptance by other group members. Research finds that constructs related to racial centrality, such as a bond with racial ingroup members (Driedger, 1976) and ethnic group identification (AhnAllen, Suyemoto, & Carter, 2006), have been positively related to a sense of group belongingness. Similarly, constructs related to perceptions of belongingness such as racial-ethnic socialization (Rivas-Drake, Hughes, & Way, 2009) and familial support (e.g., maternal support; Caldwell, Zimmerman, Bernat, Sellers, & Notaro, 2002) have been linked to racial private regard. We also theorized that a greater sense of belonging and acceptance by other group members would be associated with increases in psychological well-being. Accordingly, research has found that a sense of belongingness and connection is linked to positive psychological adjustment (e.g., Van Ryzin, Gravely, & Roseth, 2009), and some view belongingness as a fundamental human need (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, 1995).

On the other hand, individuals’ beliefs about how others view African Americans may be related to lower life satisfaction through perceptions of discrimination. Because public regard captures perceptions of how racial out-groups view one’s racial group, it may be associated with perceived discrimination from these out-groups. Correspondingly, past literature demonstrates that racial discrimination is associated with lower public regard (Rivas-Drake et al., 2009; Sellers et al., 2003; Sellers et al., 2006; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). We also theorized that perceptions of discrimination would be negatively related to life satisfaction, consistent with studies linking discrimination and stigma with decreased psychological well-being and adjustment (e.g., Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers, & Jackson, 2008; Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers, & Jackson, 2010; Seaton & Yip, 2009; Verkuyten, 2008).

In sum, we theorized that feelings of belongingness might be the mechanism through which racial centrality and private regard relate to life satisfaction, whereas perceptions of discrimination might be the mechanism through which racial public regard relates to life satisfaction. We did not predict that perceptions of belongingness would mediate this relationship since public regard primarily concerns one’s perceptions of other groups’ opinions of one’s group. Similarly, we did not predict that perceptions of discrimination would mediate the association of centrality or private regard with life satisfaction because those dimensions tap individuals’ personal racial group perceptions and the insulation hypothesis suggests African Americans’ personal sense of self is relatively protected from outgroup perceptions of their group (Broman, Neighbors, & Jackson, 1988).

Intersectionality theory suggests the importance of considering how one’s race and gender may jointly affect psychological outcomes (Cole, 2009; Settles, 2006). Consistent with this theory, the degree to which these identity functions mediate the association between racial identity and life satisfaction may differ by gender. For example, there has been work suggesting that compared with men, women are more relationship oriented and have a more interdependent self construal (Cross & Madson, 1997). Thus, women’s life satisfaction may benefit more than men’s from the support and belongingness associated with higher racial identity. Similarly, some research also suggests that men are more likely to be the targets of racial discrimination than women (e.g., Navarrete, McDonald, Molina, & Sidanius, 2010), particularly from police and within the legal system (Fine & Weis, 1998; Krieger & Sidney, 1996). Thus, the negative impact of perceptions of discrimination on life satisfaction may be greater for men than women. In sum, we suggest that racial identity may serve different functions for men and women, and that the psychological processes that link racial identity to well-being also differ by gender.

Life satisfaction, our primary outcome, is a global assessment of one’s quality of life (Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, 1985), and is considered to be a core aspect of subjective well-being (Diener, 1984). Such subjective well-being measures permit respondents (rather than researchers) to determine the standard to which they compare their lives (Diener, 1984). Measures of life satisfaction have been used extensively in studies spanning multiple nations, ethnic groups and cultures (e.g., Inglehart, Foa, Peterson, & Welzel, 2008). Empirical research exploring the association between racial identity and life satisfaction is limited. However, several studies have found that there is a positive relationship between collective self-esteem and life satisfaction (Crocker, Luhtanen, Blaine, & Broadnax, 1994; Cha, 2003; Mokgatlhe & Schoeman, 1998; Zhang, 2005). Given the substantial theoretical overlap between the constructs of racial identity and collective self-esteem, we hypothesized that racial identity and life satisfaction would be positively related as well.

In sum, we tested the following three hypotheses using a community sample of African American women and men living in Michigan.

Hypothesis 1: Higher levels of racial centrality, racial public regard, and racial private regard will be related to higher life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2: Perceptions of belongingness will mediate the relationship between racial centrality and life satisfaction, and racial private regard and life satisfaction. In contrast, perceptions of discrimination will mediate the relationship between racial public regard and life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3: The relationships mediated by belongingness (racial centrality and life satisfaction [Hypothesis 3a] and racial private regard and life satisfaction [Hypothesis 3b]) will be stronger for women than men and the relationship mediated by discrimination (racial public regard and life satisfaction [Hypothesis 3c]) will be stronger for men than women.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Survey Sampling International (SSI) provided the names and addresses of 1,000 people residing in Michigan. Because the goal of the study was to obtain a sample of African American and White individuals, SSI used information from the U.S. Census to identify census tracts with these racial groups. We also recruited people via “snowball” sampling of original sample participants, garnering an additional 143 potential participants. Individuals were mailed a paper-and-pencil survey packet and a postage-paid return envelope. Upon receipt of a completed survey packet, participants were mailed $20. Overall, 1,143 individuals were solicited for study participation, from which we received 356 responses (31.1% response rate). The present study examines the subsample of 161 African American participants (45.2% of full sample), who ranged in age from 18 to 86 years (M = 48.8; SD = 16.9). Additional demographic characteristics can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 91 (56.5) |

| Male | 70 (43.5) |

| Highest education level completed | |

| Some high school | 24 (14.9) |

| High school | 30 (18.6) |

| Some college | 62 (38.5) |

| College | 13 (08.1) |

| Some graduate school | 9 (05.6) |

| Graduate school | 17 (10.6) |

| Born in United States | |

| Yes | 159 (98.8) |

| No | 2 (01.2) |

Measures

Descriptive statistics and scale reliabilities are shown in Table 2. Except for participant gender, measures used a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). For all scales, appropriate items were reverse scored and then an average score was calculated such that higher scores indicated higher levels of the construct.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Centrality | 5.72 | 1.21 | (.82) | ||||||

| 2. Private regard | 6.38 | 0.82 | .67* | (.73) | |||||

| 3. Public regard | 4.00 | 1.53 | .18* | .13 | (.84) | ||||

| 4. Belongingness | 5.33 | 0.88 | .48* | .42* | .07 | (.65) | |||

| 5. Discrimination | 4.43 | 0.97 | .07 | .03 | − .34* | .05 | (.65) | ||

| 6. Life satisfaction | 4.42 | 1.46 | .23* | .20* | .20* | .29* | −.22* | (.88) | |

| 7. Gender | — | — | − .11 | −.07 | .07 | .07 | −.19* | .08 | — |

Note. Numbers in parentheses are Cronbach’s alphas. 0 = male; 1 = female.

p< .05.

Gender

Participants responded to the question “What is your gender?” by checking either “male” (0) or “female” (1).

Racial identity

Racial identity was measured with three abbreviated subscales of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997). We used 4 items from the Centrality subscale, which assessed the importance of race to the self (e.g., “Being a member of my racial group is an important reflection of who I am”). We used 3 items from the Private Regard subscale, which assessed the degree to which respondents feel positively toward their racial group and being a racial group member (e.g., “I am proud to be a member of my race”). We used 3 items from the Public Regard subscale, which assessed respondents’ perceptions of how the larger society views their racial group (e.g., “Overall, people of my race are considered good by others”).

Racial identity functions

Our two identity functions measures (Perceptions of Discrimination and Perceptions of Group Belongingness) were developed based on a prior qualitative study of Black and White men and women’s perceptions of their race and gender identity functions (see Settles, Pratt-Hyatt, & Buchanan, 2008 for details on study procedures). Twelve focus groups were conducted; 3 each for Black men (n = 10), Black women (n = 14), White men (n = 12), and White women (n = 17). From transcribed focus group discussions, eight coders identified emergent themes, and then the coders created scales tapping the themes developed from the focus groups. Although there are existing measures assessing constructs similar to the scales created for present study, they did not fully reflect the concerns and issues raised by the focus group participants. The average interitem correlation for our discrimination and belongingness scales were .3 and .2, respectively, suggesting that they are tapping into relatively broad constructs, but are still within the range of optimal homogeneity (Briggs & Cheek, 1986). The breath of these measures also may account for their relatively low alphas (Table 2).

Perceptions of discrimination

Perceptions of discrimination were measured with an 8-item scale created for the present study. The scale assessed the degree to which respondents have faced life difficulties and negative treatment from others based on their race (e.g., “I experience discrimination in many aspects of my life, such as work, at school, when shopping, and choosing a place to live”; “Compared to people of other races, I have to work harder to prove myself ”), and taps into discrimination in educational attainment and work, from the police and criminal justice system, as well as more general difficulties. This measure was significantly correlated with the Harrell (1994) Daily Racist Hassles Scale (r = .40, p < .05), suggesting that it is assessing a distinct but related aspect of discrimination.

Perceptions of group belongingness

Perceptions of group belongingness were measured with an 8-item scale created for the study. The scale measured the degree to which respondents have garnered support or a sense of belongingness from their family, community and racial group (e.g., “People in the neighborhood I grew up in were like an extended family”; “I share a strong sense of culture with others of my race based on our history and traditions”). This measure was significantly correlated with the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988; r = .33, p < .05), again suggesting that it taps into a distinct but related component of social support.

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985), a 5-item global measure of life satisfaction that assessed the degree to which one is satisfied with general conditions of one’s life (e.g., “In most ways, my life is close to ideal”).

Results

Bivariate correlations, descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alphas are presented in Table 2. Hypothesis 1 posited that each racial identity dimension would be related to life satisfaction. Racial centrality, public regard, and private regard were all significantly positively related to life satisfaction (Table 2; Figure 1). Thus, individuals who perceived being African American as more important, viewed African Americans more positively, or believed that others viewed African Americans more positively reported being more satisfied with their lives.

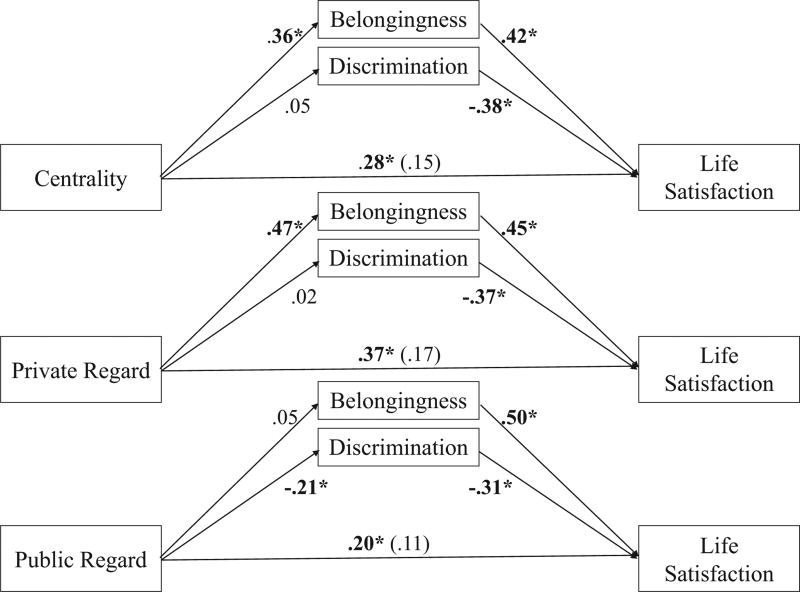

Figure 1.

The mediating role of perceptions of discrimination and belongingness in the relation between centrality and life satisfaction (top), private regard and life satisfaction (middle panel), and public regard and life satisfaction (bottom). Note. Coefficients are unstandardized; those in parentheses represent the direct effect with the mediators in the model. * p < .05.

Hypothesis 2: Multiple Mediation Models

To test Hypothesis 2, we assessed whether belongingness and discrimination mediated the relationship between each identity dimension and life satisfaction. In each of three analyses, one of the identity dimensions was the predictor, life satisfaction was the outcome, and the two mediators were entered simultaneously and allowed to correlate with each other.1

Our results suggested that the necessary relationships for mediation were present (Figure 1). Racial centrality and private regard were positively associated with belongingness. In contrast, public regard was negatively associated with discrimination. Furthermore, perceptions of greater belongingness were related to higher life satisfaction whereas perceptions of more discrimination from others were related to lower life satisfaction. Finally, our results showed that after belongingness and discrimination were taken into account, the direct effects of racial centrality, private regard, and public regard on life satisfaction became nonsignificant, representing mediation for all three models and support for Hypothesis 2. Further analyses to examine whether one or both of the mediators accounted for the significant mediation (Table 3) indicated that belongingness mediated the effects of centrality and private regard, but not public regard, on life satisfaction. Moreover, discrimination mediated the effects of public regard, but not centrality or private regard, on life satisfaction.2 Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Table 3.

Estimates (and 95% Bootstrapping Confidence Intervals) for Specific and Conditional Indirect Effects

| Mediator

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belongingness

|

Discrimination

|

|||||

| Belongingness | Discrimination | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Centrality | 0.15 (0.05, 0.28) | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.03) | .21 (0.09, 0.35) | .01(−0.17, 0.18) | — | — |

| Private regard | 0.21 (0.08, 0.41) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.05) | .28 (0.12, 0.50) | .02 (−0.19, 0.28) | — | — |

| Public regard | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.08) | 0.07 (0.02, 0.16) | — | — | .07 (−0.01, 0.17) | .02 (−0.02, 0.12) |

Note. 95% confidence intervals were created using 5,000 bootstrap resamples (bias corrected), as recommended by Shrout and Bolger (2002).

Hypothesis 3: Moderated Mediation Models

Hypothesis 3 proposed that belongingness would be a stronger mediator for women than men, and discrimination would be a stronger mediator for men than women. This represented a pattern of moderated mediation, which is characterized by a mediating effect that is moderated by another variable (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). We tested whether gender moderated the mediation at two points in the model: in the relationship between each identity dimension and each mediator, and in the relationship between each mediator and life satisfaction. If either interaction is significant, moderated mediation is demonstrated (and Hypothesis 3 would be supported) because this indicates that the mediating effect of the identity dimension on life satisfaction, via identity function, differs in strength for women and men.

To Test Hypothesis 3, we first ran a separate moderated mediation analysis for each identity function mediator with each identity predictor. In each of these six analyses, the identity predictor (centrality, private regard, or public regard), gender, the identity function mediator (belongingness or discrimination), the interaction between the identity predictor and gender, the interaction between the identity function mediator and gender, and life satisfaction were entered simultaneously.3,4 Any moderated mediation models with significant interaction terms were then reanalyzed separately for women and men (Table 3).5

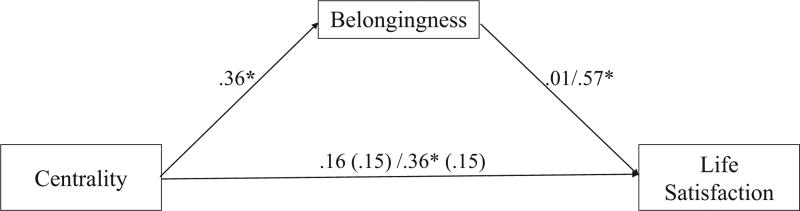

The results of the two moderated mediation analyses with racial centrality as the predictor variable in each model indicated that there was no significant interaction between gender and centrality predicting belongingness (b = 0.06, (β = 0.06, ns). However, the interaction between belongingness and gender was significant in predicting life satisfaction (b = 0.65, (β = 0.32, p < .05) such that the relationship between belongingness and life satisfaction, controlling for racial centrality, was significant for women but not men (Table 3; Figure 2). Thus, belongingness mediated the association between centrality and life satisfaction for women only, supporting Hypothesis 3a. In contrast, there was no evidence that centrality significantly predicted life satisfaction in men. Regarding discrimination as the mediator, there were no significant interactions of gender with centrality predicting discrimination (b = −0.11, (β = −0.11, ns), or with discrimination predicting life satisfaction (b = 0.19, (β = 0.09, ns).

Figure 2.

Gender as a moderator of the mediating role of belongingness in the relation between centrality and life satisfaction. Note. Coefficients are unstandardized; those in parentheses represent the direct effect with the mediator in the model. Coefficients left of the slash represent values for men, coefficients right of the slash represent values for women. * p < .05.

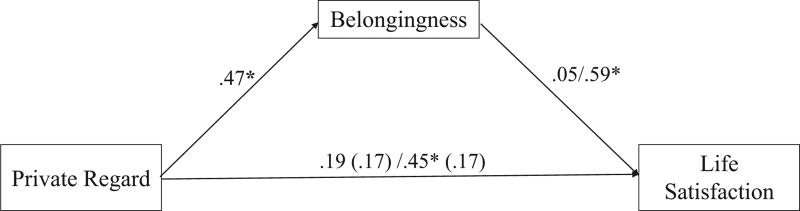

A similar pattern emerged in the models where private regard was the predictor variable. Although the interaction of gender and private regard predicting belongingness was not significant (b = 0.07, (β = 0.05, ns), the interaction between belongingness and gender was significant in predicting life satisfaction (b = 0.60, (β = 0.29, p < .05); the relationship between belongingness and life satisfaction, controlling for private regard, was significant for women but not men (Table 3; Figure 3). Again, belongingness mediated the association between private regard and life satisfaction for women only, supporting Hypothesis 3a. In contrast, there was no evidence that private regard significantly predicted life satisfaction in men. For discrimination as the identity function mediator, there was no interaction of gender and private regard predicting discrimination (b = −0.34, (β = −0.21, ns), or between gender and discrimination predicting life satisfaction (b = 0.22, (β = 0.11, ns).

Figure 3.

Gender as a moderator of the mediating role of belongingness in the relation between private regard and life satisfaction. Note. Coefficients are unstandardized; those in parentheses represent the direct effect with the mediator in the model. Coefficients left of the slash represent values for men, coefficients right of the slash represent values for women. * p < .05.

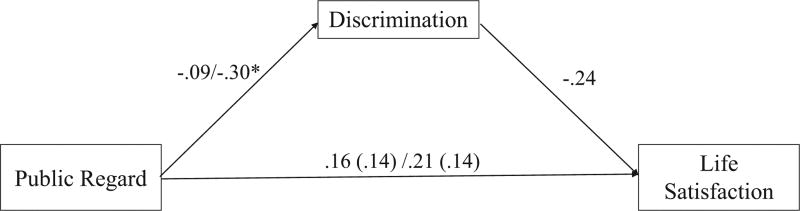

The final set of analyses included public regard as the predictor variable. For belongingness as a mediator, our results suggest that there was a significant interaction between public regard and gender predicting belongingness (b = 0.25, (β = 0.31, p < .05). Specifically, higher public regard was positively related to belongingness in women, but these variables were unrelated in men. However, the relationship between public regard and life satisfaction did not show mediation by belongingness (Table 3). Furthermore, there was not a significant interaction of gender and belongingness predicting life satisfaction (b = 0.43, (β = 0.21, ns). The results for discrimination as a mediator show a significant interaction between public regard and gender predicting discrimination (b = −0.23, (β = −0.28, p < .05). Specifically, higher public regard was related to lower perceptions of discrimination for women, but these variables were unrelated for men, contrary to Hypothesis 3b (Table 3; Figure 4). However, the analysis revealed that the indirect effect of public regard on life satisfaction via discrimination was nonsignificant when discrimination was examined singly as a mediator (Figure 4). That is, although previous analyses indicated that discrimination was a significant mediator of the relationship between public regard and life satisfaction when belongingness was also included as a mediator in the model, there is no evidence that the relationship between public regard and life satisfaction is mediated by discrimination alone. Thus, we failed to find evidence for a pattern of moderated mediation. Finally, the interaction of gender and discrimination predicting life satisfaction was not significant (b = 0.32, (β = 0.16, ns).

Figure 4.

Gender as a moderator of the mediating role of discrimination in the relation between public regard and life satisfaction. Note. Coefficients are unstandardized; those in parentheses represent the direct effect with the mediator in the model. Coefficients left of the slash represent values for men, coefficients right of the slash represent values for women. * p < .05.

Discussion

The present study examined the association between three dimensions of racial identity and life satisfaction in a community sample of African Americans. We explored the nature of these relationships, examined whether these relationships were mediated by two identity functions, and tested whether these mediated relationships differed by gender. Our first hypothesis was that higher centrality, private regard and public regard would be related to higher life satisfaction. In support of Hypothesis 1, the results indicated that when African Americans define themselves more in terms of race, view their own racial group more positively, or believe other groups view their racial group more positively, they also report being more satisfied with their lives. In the existing literature, private regard has been most consistently related to psychological well-being (e.g., Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Settles et al., 2010). In contrast, the relationships to well-being for racial centrality and racial public regard have been more mixed. Our results support the notion of the positive impact of racial identity for African Americans for all three identity dimensions we examined. This bolsters the important role that positive perceptions about one’s racial group have on personal well-being.

Our second hypothesis was supported, as belongingness mediated the effects of centrality and private regard on life satisfaction, and discrimination mediated the effect of public regard on life satisfaction when both mediators were examined together. Overall, our results support our notion that identity functions may help to explain the relationship between identity and well-being. Identities are not just static group memberships, but they can “do” something for identity holders. Yet, we suggest that what identities are perceived as doing for individuals may vary by the identity as well as by the identity dimension, as our results suggest. Our results imply that a function of racial centrality and private regard is to connect the individual to the group. A function of racial public regard may be to serve as a metric for the groups’ treatment by others. Certainly, racial identity may serve other functions than those studied presently. In addition, because of the correlational nature of our study, we can only speculate as to the causal ordering of the proposed mediating relationships. Further research in this area would be worthwhile.

We found that the pattern of mediation differed for men and women, partially supporting our third hypothesis. Specifically, racial centrality and private regard were related to belongingness for both genders, but belongingness was related to higher life satisfaction (controlling for centrality or private regard) only for women. These gender differences are consistent with past work suggesting that women are more relationship focused (e.g., Cross & Madson, 1997). Thus, a sense of belonging may affect women’s life satisfaction more than men’s. A similar explanation may explain the unexpected simple (i.e., nonmediated) interaction we observed in which for women only, perceiving higher public regard was related to perceiving less discrimination. That is, women may take others’ perspectives into account—use reflected appraisals (Cross, 1991)—when making determinations about their beliefs and attitudes about the world. Thus, just as their sense of connectedness to their racial group seems to account for why their positive racial group perceptions are related to feelings of life satisfaction, their sense of the extent to which African Americans are seen to be targets of discrimination may be linked to how much women perceive their group as being valued and accepted by others. In addition, although we found that higher public regard was related to lower perceptions of discrimination for women but not for men, the mediating effect of discrimination failed to reach significance when it was examined singly and interactions with gender were included in the analysis. This may be because of the small effect size of the initial indirect effect of public regard on life satisfaction via discrimination (Table 3). That is, there may have been insufficient power to detect such a small indirect effect once the gender interaction parameters were added to the model. We also observed a nonhypothesized interaction such that higher public regard, the belief that others view African Americans more positively, was related to greater belongingness for women only. The reason for this relationship among African American women is unclear but may again reflect the importance of others’ evaluations, even to women’s sense of self and group connectedness.

These results provide evidence that the link between racial identity and well-being is affected by gender and suggest that racial identity may serve differing functions for men and women. In order to gain a full understanding of identity and identity processes, one must consider the fact that individuals by necessity exist in multiple social categories (Cole, 2009; Urban & Miller, 1998). Indeed, there is clear evidence that the processes that link racial identity to well-being differ across men and women, and the general associations between these variables seem accounted for mainly by women. Thus, group belongingness may be a function of racial identity with consequences for well-being that are unique to women. More work is needed to discover what functions of racial group membership are relevant to African American men’s lives.

Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation of this study is that, because all participants were recruited from Michigan, results from this sample may not generalize to the experiences of other African American populations. For example, perhaps discrimination would significantly mediate the relationship between identity and life satisfaction in areas of the United States where there is a stronger history of discrimination against African Americans (e.g., the south). Furthermore, because study recruitment used mailed surveys and an adult community sample, our final sample was somewhat small, although still sizable for this type of study. Despite these limitations, use of a community sample of African American adults from a wide variety of educational and socioeconomic backgrounds, rather than university undergraduates, is a substantial strength of the present study that we feel offsets some of the limitations outlined above. Future studies should replicate these findings and determine the extent to which they are generalizable, for example, by examining whether these results can be extended to different indicators of psychological well-being such as self-esteem and depression. Research could also explore whether the observed relationships between identity, identity functions and well-being can be extended to other types of identities (e.g., gender identity) or whether there are additional identity functions that serve as mediators of these relationships.

Conclusion

The present study adds to the literature regarding the psychological benefits of group identification. Our results suggest that racial identity, for African Americans, has a positive impact on their life satisfaction. Furthermore, this study begins to address the question of why racial group identification has such implications for psychological well-being. Our findings suggest that group belongingness is one mechanism that explains this relationship; that is, positive perceptions of African Americans are related to participants’ life satisfaction because it leads them to feel more connected to their racial group. Yet, this process was only found to exist for women in our study. Thus, more work is needed to determine the range of racial identity functions, and which operate for women, men, or both groups. Although a weaker finding, this study also suggests that beliefs that others view African Americans more positively is related to life satisfaction because it leads individuals to perceive less racial discrimination, but mainly for women. In sum, although many questions remain, this study makes an advance in the racial identity literature by taking a step toward understanding the process by which identity relates to life satisfaction.

Footnotes

We used multiple mediator models rather than testing separate simple mediation models to compare the relative magnitude of the specific indirect effects of each mediator, and to reduce the likelihood of biased parameter estimates attributable to the omitted variable problem (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Although the significance test for the specific indirect effect of discrimination resulted in a p = .056, the bootstrapping confidence interval of this indirect effect did not include 0. According to Shrout and Bolger (2002), bootstrapping was a more appropriate test given the small sample size of this study.

We grand mean centered the identity dimensions and identity functions to avoid multicollinearity when creating the interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991). Examining belongingness and discrimination individually as mediators is justified given that the initial multiple mediator analyses showed that they were uncorrelated; thus, the estimates of specific indirect effects in the multiple mediator analyses approximate the estimates of indirect effects of each mediator entered alone (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

The complete results and all regression coefficients arising from these six moderated mediation analyses are available upon request from the first author.

Paths that did not show significant gender interactions were constrained to be equal across men and women while paths showing gender moderation were allowed to vary between men and women. These follow-up analyses allow for the estimation of the conditional indirect effects (i.e., whether the indirect effects differ for men and women) and the test of whether each of these conditional indirect effects are significantly different from zero (i.e., whether relationships are significant for each gender). We used 5000 bootstrap resamples to create the 95% confidence interval using Mplus5 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007).

Contributor Information

Stevie C. Y. Yap, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University

Isis H. Settles, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University

Jennifer S. Pratt-Hyatt, Department of Psychology, Sociology, and Counseling, Northwest Missouri State University

References

- AhnAllen JM, Suyemoto KL, Carter AS. Relationship between physical appearance, sense of belonging and exclusion, and racial/ethnic self-identification among multiracial Japanese-European Americans. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:673–686. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe N, Schmitt M, Harvey R. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs SR, Cheek JM. The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. Journal of Personality. 1986;54:106–148. [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial group identification among Black adults. Social Forces. 1988;67:146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum MS, Best C, Barnes SL, Burton ET. Private regard, identity protection and perceived racism among African American males. Journal of African American Studies. 2008;12:142–155. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA, Bernat DH, Sellers RM, Notaro PC. Racial identity, maternal support and psychological distress among African American adolescents. Child Development. 2002;73:1322–1336. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha KH. Subjective well-being among college students. Social Indicators Research. 2003;62:455–477. [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64:170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Luhtanen R, Blaine B, Broadnax S. Collective self esteem and psychological well-being among White, Black, and Asian college students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20:503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Madson L. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE., Jr . Shades of black: Diversity in African-American identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Jr, Strauss L. The everyday functions of African-American identity. In: Swim JK, Stangor C, editors. Prejudice: The target’s perspective. New York: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 268–279. [Google Scholar]

- Deaux K, Martin D. Interpersonal networks and social categories: Specifying levels of context in identity processes. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2003;66:101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:542–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driedger L. Ethnic self-identity: A comparison of ingroup evaluations. Sociometry. 1976;39:131–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine M, Weis L. Crime stories: A critical look through race, ethnicity, and gender. Qualitative Studies in Education. 1998;11:435–459. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. The Racism and Life Experience scales. 1994 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA. Social identity theory. In: Burke PJ, editor. Contemporary social psychological theories. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press; 2006. pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R, Foa R, Peterson C, Welzel C. Development, freedom, and rising happiness: A global perspective (1981–2007) Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:264–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, Liu WM. The impact of racial identity, ethnic identity, Asian values, and race-related stress on Asian Americans and Asian international college students’ psychological well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:79–91. doi: 10.1037/a0017393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Yip T, Gonzales-Backen M, Witkow M, Fuligni AJ. Ethnic identity and the daily psychological well-being of adolescents from Mexican and Chinese backgrounds. Child Development. 2006;77:1338–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: The CARDIA study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Spencer SJ, Schmader T, Wolfe CT, Crocker J. Coping with negative stereotypes about intellectual performance: The role of psychological disengagement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna KYA, Bargh JA. Coming out in the age of the Internet: Identity de-marginalization’ from virtual group participation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:681–694. [Google Scholar]

- Mokgatlhe BP, Schoeman JB. Predictors of satisfaction with life: The role of racial identity, collective self-esteem and gender-role attitudes. South African Journal of Psychology. 1998;28:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5. Los Angeles: Author; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete CD, McDonald M, Molina L, Sidanius J. Prejudice at the nexus of race and gender: An out-group male target hypothesis. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2010;98:933–945. doi: 10.1037/a0017931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7:156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Alipuria LL. Ethnic identity in college students from four ethnic groups. Journal of Adolescence. 1990;13:171–183. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(90)90006-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Assessing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multi-variate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Hughes D, Way N. A preliminary analysis of associations among ethnic- racial socialization, ethnic discrimination, and ethnic identity among diverse urban sixth graders. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:558–584. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SAJ, Sellers RM, Chavous TM, Smith M. The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:715–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1288–1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. An intersectional approach for understanding perceived discrimination and psychological well-being among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1372–1379. doi: 10.1037/a0019869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Yip T. School and neighborhood contexts, perceptions of racial discrimination and psychological well-being among African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:153–163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9356-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA. The role of racial identity and racial discrimination in the mental health of African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis RL. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, Smith M. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: Preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:805–815. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM. Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptu-alization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles IH. Use of an intersectional framework to understand Black women’s racial and gender identities. Sex Roles. 2006;54:589–601. [Google Scholar]

- Settles IH, Navarrete CD, Pagano S, Sidanius J, Abdou C. Ethnic identity and depression among African-American women. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:248–255. doi: 10.1037/a0016442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles IH, Pratt-Hyatt JS, Buchanan NT. Through the lens of race: Black and White women’s perceptions of their gender. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:454–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of inter-group relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Umanña-Taylor AJ. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: Examining the role of social context. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban LM, Miller N. A theoretical analysis of crossed categorization effects: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:894–908. [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Chae M, Brown C, Kelly D. Effect of ethnic group membership on ethnic identity, race-related stress, and quality of life. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8:366–377. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Gravely AA, Roseth CJ. Autonomy, belongingness, and engagement in school as contributors to adolescent psychological well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M. Life satisfaction among ethnic minorities: The role of discrimination and group identification. Social Indicators Research. 2008;89:391–404. [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Cross WE. A daily diary study of mental health and community involvement for three Chinese American social identities. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:394–408. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, Sellers RM. African American racial identity across the lifespan: A cluster analysis of identity status, identity content and depression among adolescents, emerging adults and adults. Child Development. 2006;77:1504–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. Prediction of Chinese life satisfaction: Contribution of collective self-esteem. International Journal of Psychology. 2005;40:189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]