Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infects 200 million people globally, and 60–80% of cases persist as a chronic infection that will progress to cirrhosis and liver cancer in 2–10% of patients1–3. We recently demonstrated that HCV induces aberrant expression of two host microRNAs (miRNAs), miR-208b and miR-499a-5p, encoded by myosin genes in infected hepatocytes4. These miRNAs, along with AU-rich-element-mediated decay, suppress IFNL2 and IFNL3, members of the type III interferon (IFN) gene family, to support viral persistence. In this study, we show that miR-208b and miR-499a-5p also dampen type I IFN signaling in HCV-infected hepatocytes by directly down-regulating expression of the type I IFN receptor chain, IFNAR1. Inhibition of these miRNAs by using miRNA inhibitors during HCV infection increased expression of IFNAR1. Additionally, inhibition rescued the antiviral response to exogenous type I IFN, as measured by a marked increase in IFN-stimulated genes and a decrease in HCV load. Treatment of HCV-infected hepatocytes with type I IFN increased expression of myosins over HCV infection alone. Since these miRNAs can suppress type III IFN family members, these data collectively define a novel cross-regulation between type I and III IFNs during HCV infection.

HCV is a single-stranded hepatotropic RNA virus against which no vaccine currently exists. Previously, the standard of care for chronic HCV infection was combination treatment with pegylated IFN-α (pegIFN-α) and ribavirin, which produced a sustained virological response in fewer than 40% of patients5. With the addition of protease inhibitors, a type of direct-acting antiviral (DAA), to pegIFN-α and ribavirin therapy, viral cure rates have improved to 56–95% of patients; the exact rate is dependent on both virus and host factors6–9. Following this success, therapeutic advancements have focused on interfering with the viral lifecycle, and many new DAA drugs are currently in clinical trials6,10. More recently, interferon-free combinations of HCV protease and RNA polymerase inhibitors, sometimes with ribavirin, have produced dramatic results in a subset of patients10. However, the emergence of resistant HCV variants and the high cost of DAA treatments might limit the availability of these therapies worldwide11–13. The usefulness of DAA-based therapies for some patients—such as those with advanced infection, who are at the highest risk for hepatic decompensation, liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma and/or death—also remains to be fully proven13. Hence, it is critical to identify the mechanisms that HCV employs which lead to the failure of type I IFN therapy. In this study, we show that HCV dampens type I IFN signaling by targeting IFNAR1 mRNA expression. This novel mechanism not only provides insight into why IFN-based HCV therapies have failed but also suggests why the interferon lambda 3 (IFNL3) genotype correlates with the outcome of type I IFN treatment.

Several viral and host factors are predictive of HCV clearance, including viral genotype, baseline viral load and host genotype. Genome-wide association studies have identified three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) near the antiviral IFNL3 gene that associate with natural clearance of HCV14,15 and patient response to therapy14,16–18. Ensuing studies have since identified four genetic variants in linkage disequilibrium with the primary tag SNPs19–21. One of these variants, rs368234815, is a dinucleotide frameshift variant that creates IFNL4, a gene upstream of IFNL3 (ref. 22). Paradoxically, expression of IFNL4 correlates with viral persistence. The mechanism behind this correlation has yet to be fully elucidated. We identified rs4803217, located in the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of IFNL3, as a functional SNP that determines HCV clearance by altering IFNL3 expression4. We further showed that the protective allele (G/G, rs4803217) increases expression of IFNL3 by escaping both AU-rich element-mediated decay and post-transcriptional regulation by HCV-induced miRNAs, miR-208b and miR-499a-5p. IFNλ3 is a potent antiviral cytokine that induces expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). A recent study using ex vivo HCV-infected primary human hepatocytes demonstrated that the favorable IFNL3 genotype correlates with high ISG expression and subsequent antiviral activity in HCV-infected and adjacent cells23. In contrast, the magnitude of ISG expression in HCV-infected livers before IFN therapy has been shown to negatively correlate with response to pegIFN-α therapy24. This disparity underlines the complexity of IFN signaling in HCV infection, as well as how much remains to be understood about the interplay between virus, host and IFN therapies.

Beyond its ability to predict natural clearance of HCV, IFNL3 genotype is also the strongest predictor of patient response to pegIFN-α plus ribavirin therapy: patients with the unfavorable allele are less likely to respond to this therapy than those with the favorable allele14,16–18. This association between IFNL3 genotype and response to pegIFN-α therapy suggests a possible cross-regulation of these pathways during infection, yet the mechanisms guiding this are unknown.

Factors have been identified within the type I IFN signaling pathway that correlate with the success of pegIFN-α and ribavirin therapy, among them the expression of IFNAR1 in the liver25,26. IFNAR1 is a subunit of the type I IFN receptor composed of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 chains. Studies have found that patients with high hepatic IFNAR1 mRNA responded better to IFN therapy, whereas patients who relapsed or did not respond to IFN therapy had intermediate or low hepatic IFNAR1 mRNA, respectively27–31. Since these clinical observations, studies have demonstrated that in vitro HCV infection or treatment of hepatocyte cells with a HCV subgenomic replicon induces the unfolded protein or endoplasmic reticulum stress response in hepatoma cells that indirectly decreases IFNAR1 protein levels32,33. While these data provide insight into one mechanism regulating IFNAR1 surface expression during HCV infection, a mechanism that explains decreased IFNAR1 mRNA levels in HCV infected patients has yet to be described. Moreover, no study has indicated a HCV-specific factor that directly reduces IFNAR1 expression.

miRNAs regulate gene expression by guiding mRNA degradation machinery to complementary sequences in the 3′ UTR of mRNAs34. We previously demonstrated that HCV infection induces expression of miR-208b and miR-499a-5p (ref. 4), two miRNAs not normally expressed in the liver. We hypothesized that within innate immune signaling pathways these miRNAs may target multiple genes in addition to IFNL2 and IFNL3. miR-208b and miR-499a-5p are termed “myomiRs” as they are encoded in the introns of two myosin-encoding genes, myosin heavy chain 7 (MYH7) and myosin heavy chain 7B (MYH7B), respectively35. Studies of miR-208b and miR-499a-5p in myofibers have shown that expression of these myomiRs correlates with expression of their respective parental genes MYH7 and MYH7B35. We found a significant correlation between transcript levels of MYH7 and MYH7B with their intronic pri-miRNAs and mature miRNAs in liver biopsies from patients chronically infected with HCV. This demonstrates that MYH7 and MYH7B expression can be used as a surrogate readout for myomiR expression4. Since HCV clearance depends on the host response to endogenous type I IFNs and/or therapeutic pegIFN-α, we were interested in determining whether these myomiRs targeted effectors in the type I IFN signaling pathway.

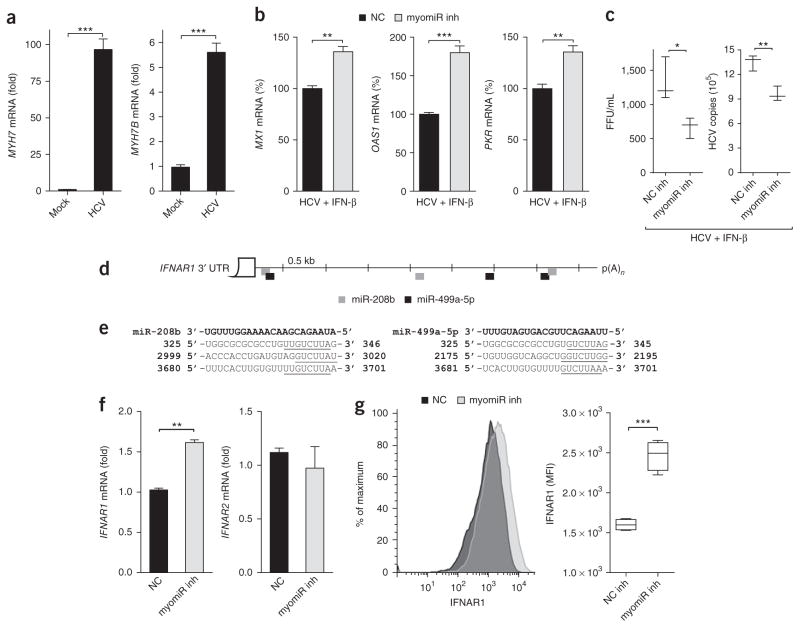

To investigate the effects of HCV-induced myomiRs on type I IFN signaling, we used previously characterized locked nucleic acid (LNA) inhibitors to inhibit endogenous miR-208b and miR-499a- 5p during HCV infection of the hepatoma cell line Huh7 (ref. 4). A LNA inhibitor with a non-targeting sequence that does not bind to any known miRNA was used as a non-targeting control (NC). Huh7 cells were transfected with myomiR inhibitors or an NC inhibitor, infected with HCV, and then treated with IFN-β. Exogenous IFN-β was used to mimic therapeutic and paracrine type I IFN signaling, as HCV disrupts signaling downstream of the helicase RIG-I (retinoic-acid-inducible gene), an essential pathogen-recognition receptor important for IFN induction. We confirmed that miR-208b, miR-499a-5p and their parental myosin genes were induced following infection as documented in our previous study4 (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a). As expected, expression of the ISGs Mx GTPase (encoded by MX1), 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS1) and the translational inhibitor PKR were all induced following IFN-β stimulation (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, induction of these ISGs was significantly higher in cells treated with the myomiR inhibitors compared to the non-targeting control. Increased ISG expression in myomiR inhibitor-transfected cells correlated with decreases in viral titer and RNA copy number (Fig. 1c). The effect of the inhibitors was dependent on HCV infection and IFN- β treatment, as there was no difference in ISG expression in either HCV-infected cells treated with inhibitors or mock-infected cells treated with IFN-β (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c). In this system, type III IFNs had no measurable effect, and the difference seen in ISG expression was downstream of type I IFN in the presence of myomiRs (Supplementary Text 1; Supplementary Fig. 2a–e). Together these findings suggested that myomiR-regulated factor(s) influenced hepatocyte responsiveness to IFN-β and, importantly, that myomiR inhibition improved the anti-HCV response.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of miR-208b and miR-499a-5p during HCV infection improves hepatocyte response to IFN-β by increasing IFNAR1. (a) Expression of MYH7 and MYH7B in Huh7 cells infected with HCV MOI 1.0 for 48 h. (b) Expression of ISGs MX1, OAS1 and PKR in HCV-infected Huh7 cells transfected with inhibitors against miR-208b and miR-499a-5p (myomiR inh) or non-targeting control inhibitor (NC) for 48 h and then treated with IFN-β for 6 h. (c) HCV viral titer and copy number from samples in b. (d,e) RNA hybrid analysis was used to show miRNA–target interactions for miR-208b and miR-499a-5p, which bind to numerous sites of the IFNAR1 3′ UTR. (d) Schematic of miR-208b and miR-499a-5p binding sites on the IFNAR1 3′ UTR. p(A)n, poly(A) site. (e) Sequence alignment of miR-208b and miR-499a-5p and their binding sites in the IFNAR1 3′ UTR; miRNA–target seed regions are underlined and nucleotides for IFNAR1 3′ UTR are indicated. (f) Levels of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 mRNA and (g) IFNAR1 surface protein expression in HCV-infected Huh7 cells transfected with myomiR inh or NC inh. Gene expression for a–c,f was assessed using qPCR, and the reference sample for relative quantification was (a–c) mock-infected cells transfected with myomiR inhibitors or NC inhibitor assayed at 48 h or (f) HCV-infected cells transfected with NC inhibitor assayed at 48 h. Data are from one experiment representative of three or more experiments (a,b,f, mean ± s.e.m.; c,g, box and whisker plots show median values (line), 50th percentile values (box outline) and minimum and maximum values (whiskers)). Unpaired Student’s t-test was used for all statistical comparisons; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

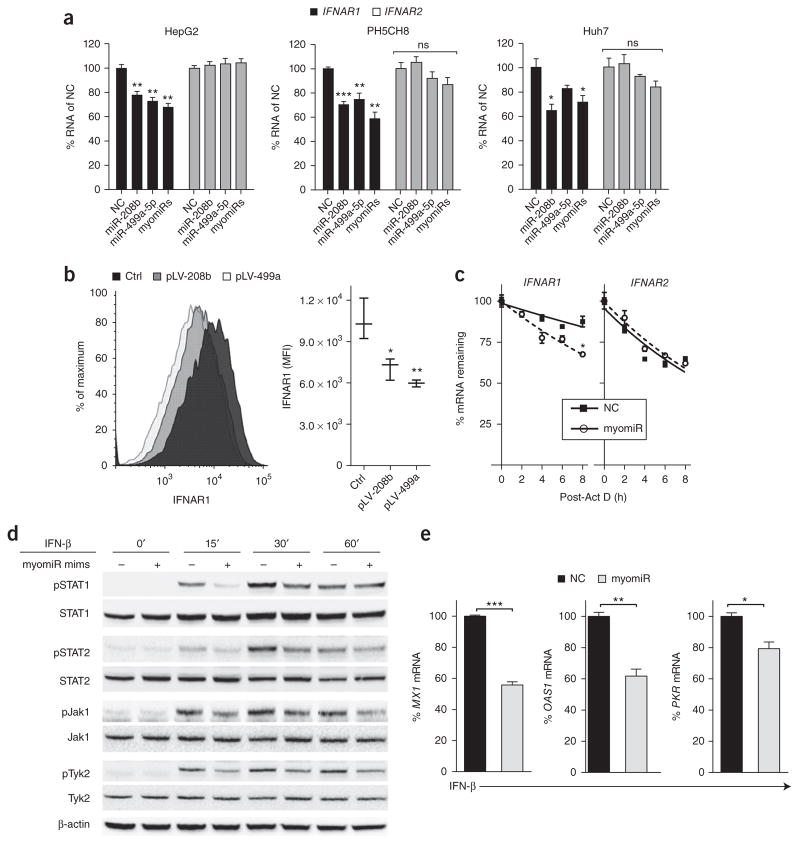

As our data revealed that myomiR inhibition increased expression of multiple antiviral ISGs during HCV infection, we hypothesized that myomiRs may target an upstream effector in the type I IFN pathway. Given that reduced IFNAR1 mRNA has been reported in HCV-infected livers27–31, we investigated whether IFNAR1 mRNA could be targeted by these myomiRs. Computational analysis revealed that the IFNAR1 3′ UTR harbors multiple predicted miRNA recognition elements (MREs) for both miR-208b and miR-499a-5p (Fig. 1d,e). This suggests that these myomiRs may regulate IFNAR1. To explore this further, we transfected myomiR inhibitors or an NC inhibitor into HCV-infected Huh7 cells. We discovered that myomiR-inhibitor-transfected cells had significantly higher IFNAR1 mRNA and cell surface expression than NC-transfected cells (Fig. 1f,g). In contrast, expression of IFNAR2, which does not harbor MREs for the myomiRs in its 3′ UTR, was unaffected by the myomiR inhibitors (Fig. 1f). This demonstrated that the HCV-induced myomiRs, miR-208b and miR-499a-5p, specifically reduced expression of the IFNAR1 subunit. In a pattern similar to that seen in HCV infection (Fig. 1b), cells transfected with the myomiR mimics also showed and reduced pSTAT1 and ISG induction compared to control mimic-treated cells (Supplementary Text 2, Fig. 2a–e). To confirm IFNAR1 targeting by miR-208b and miR-499a-5p, we used a firefly luciferase reporter assay where we cloned the human IFNAR1 3′ UTR downstream of the firefly luciferase gene. We observed decreased luciferase expression when the IFNAR1 3′ UTR luciferase construct was transfected into HepG2 cells overexpressing miR-208b or miR-499a-5p (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Taken together, these observations reveal that miR-208b and miR-499a-5p antagonized type I IFN signaling by destabilizing and down-regulating IFNAR1, leading to dampened ISG expression.

Figure 2.

myomiR overexpression reduces IFNAR1 expression, dampening downstream Jak-STAT signaling and induction of ISGs. (a) IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 mRNA expression in the hepatocyte cell lines HepG2, PH5CH8, or Huh7 transfected with mimics for miR-208b, miR-499a-5p, a mixture of both mimics (myomiRs) or a control mimic (NC). Reference sample for relative expression was NC-transfected cells. ns, non-significant. (b) IFNAR1 surface protein expression in HepG2 cells stably overexpressing miR-208b (pLV-208b) or miR-499a-5p (pLV-499a-5p). (c) Stability of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 mRNA in HepG2 cells transfected with myomiR mimics or NC mimic and treated with actinomycin D to arrest new transcription, presented as mRNA remaining over time relative to that at 0 h, set as 100%. R2 ≥ 0.63 for all curve fits. Half-lives (50% mRNA remaining): IFNAR1, 34.5 h (NC) and 14.1 h (myomiR); IFNAR2, 9.9 h (NC) and 10.5 h (myomiR). *P = 0.0003 (F test). (d) Immunoblot of lysates from HepG2 cells transfected with myomiR mimics or NC mimic and stimulated with 500 IU/mL IFN-β for 0, 15, 30, or 60 min. Blot was probed for STAT1, STAT2, Jak1, Tyk2 and their phosphorylated forms. β-actin was run as a loading control. (e) Expression of ISGs MX1, OAS1 and PKR in HepG2 cells transfected with myomiR mimics or NC mimic stimulated with 500 IU/mL IFN-β for 6 h. Relative quantification was computed using the respective unstimulated cells then normalized to NC fold change and expressed as % mRNA of NC. Data are from (a) one experiment of four experiments with similar results, (b) one experiment representative of two experiments with four replicates per group or (c–e) one experiment of two experiments with similar results (a,c,e, mean ± s.e.m.; b,c,g, box and whisker plot shows median values (line) and minimum and maximum values (whiskers)). One-way ANOVA (a) or unpaired Student’s t-test (b,c,e) was used for statistical comparison, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

As myomiRs targeted components of the type I and type III IFN pathways, which are central to the antiviral response against HCV, we reasoned that understanding myomiR induction and regulation could lead to the discovery of new antiviral targets. As there is a strong correlation between expression of miR-208b and miR-499a-5p with their parental genes, we used expression of MYH7 and MYH7B as surrogate readouts for myomiR expression in the current study.

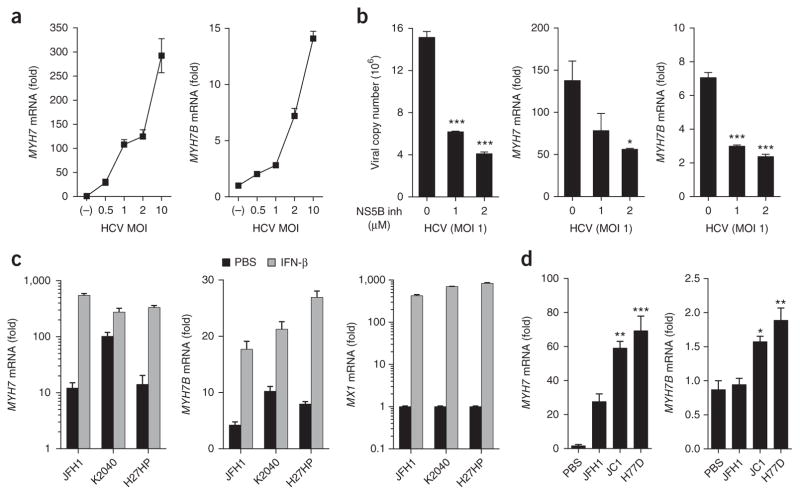

We previously showed that MYH7 and MYH7B are not induced in Huh7 cells during infection with West Nile virus or Sendai virus, nor are they induced following stimulation with the HCV 3′ UTR PAMP or poly(I:C)4. In addition, we did not observe myosin expression in Dengue virus-infected Huh7 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Thus, all data to date suggest that myomiR/myosin induction is specific to HCV infection. We have also observed that MYH7 and MYH7B expression in JFH1 HCV-infected Huh7 cells correlated with the multiplicity of infection (MOI) (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, treatment of HCV-infected Huh7 cells with a 2′-C-methyladenosine nucleoside analog inhibitor of HCV RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (NS5B) that blocks viral genome replication and reduces viral load36,37 also blocked MYH7 and MYH7B induction in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 3b). Using the HCV replicon system, we also observed that viral replication in the absence of viral entry was sufficient to induce myosin expression (Supplementary Text 3, Fig. 3c,d). These data suggested that myosin expression was dependent on viral replication.

Figure 3.

Myosin induction is dependent on viral replication. (a) Huh7 cells were infected with increasing MOIs of virus or mock-infected for 48 h and expression of MYH7 and MYH7B was assessed. (b) Huh7 cells infected with HCV for 24 h were treated with increasing doses of NS5B inhibitor. Viral copy number, MYH7 and MYH7B expression were assessed 24 h post treatment. (c) Huh7 cells harboring the Con1-derived bicistronic K2040 or high-passage (HP) subgenomic HCV RNA replicons (Huh7-K2040 and Huh7-HP cells respectively) or Huh7 cells harboring JFH-1-derived bicistronic HCV replicon were plated and 24 h later treated with PBS or 100 IU/mL IFN-β. 24 h later cells were lysed and expression of MYH7, MYH7B and MX1 was measured by qPCR. (d) PH5CH8 cells were transfected with in vitro transcribed full-length HCV RNA genomes of JFH1, JC1 or H77D HCV viral strains. 48 h post transfection, cells were lysed and expression of MYH7 and MYH7B was assessed by qPCR. Reference sample for relative quantification was (a) mock-infected cells, (b) untreated HCV-infected cells, (c) unstimulated Huh7.5 cells, or (d) untreated mock-transfected (PBS) PH5CH8 cells. Data are from (a–c) one experiment representative of two or three experiments or (d) four biological replicates pooled (a–d; mean ± s.e.m.). One-way ANOVA (a,d) or unpaired Student’s t-test (b,c) was used for statistical comparison. Welch’s correction was applied to samples in (c) with unequal variance as determined by F-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

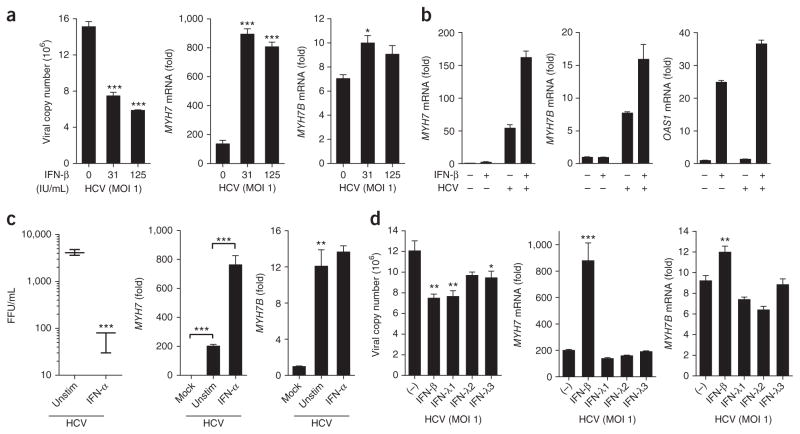

As type I and type III IFNs inhibit HCV replication, we reasoned that IFN treatment would also reduce myosin expression. Like NS5B inhibitor treatment, prolonged type I IFN treatment of HCV-infected Huh7 cells reduced viral titer and copy number (Fig. 4a–c; Supplementary Fig. 3c). However, treatment with either IFN-α or IFN-β dramatically increased MYH7 expression in HCV-infected cells compared to untreated infected cells, suggesting a role for type I IFNs in the regulation of MYH7 (Fig. 4a–c). In line with this observation, type I IFN treatment of the Huh7 cell lines Huh7-K2040, Huh7-HP and Huh7-JFH1 that harbor HCV replicons also amplified MYH7 expression (Fig. 3c). However, unlike type I IFNs, type III IFNs did not synergize with HCV to augment expression of myosin genes (Supplementary Text 4, Fig. 4a–d). These data suggest that myomiRs connect the type I and III IFN pathways during HCV infection as type I IFNs can increase myomiRs, which consequently regulate type III IFN production and type I IFN signaling (Supplementary Text 5).

Figure 4.

Type I but not type III IFNs amplify myosin expression. Huh7 cells infected with HCV MOI 1.0 for 24 h were treated with (a) increasing doses of IFN-β, (b) 31 IU/mL IFN-β, (c) 100 ng/mL of IFN-α or (d) 100 ng/mL of IFN-λ1, IFN-λ2 or IFN-λ3 or 30 IU/mL of IFN-β. 24 h post treatment, viral copy number, MYH7, MYH7B (a–c) and OAS1 (b) expression were assessed. Reference sample for relative quantification was unstimulated HCV-infected cells. Data are from one experiment representative of two or three experiments (a–d; mean ± s.e.m., c; box and whisker plots show median values (line), 50th percentile values (box outline) and minimum/maximum values (whiskers)). Unpaired Student’s t-test was used for all statistical comparisons, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. IU, international units; FFU, focus-forming units.

Here we have shown that the HCV-induced myomiRs, miR-208b and miR-499a-5p, decrease IFNAR1 expression by destabilizing its mRNA transcript. miRNA repression of IFNAR1 was sufficient to decrease IFNAR1 surface expression and dampen the antiviral response to type I IFN. During HCV infection of hepatocytes, we observed that myomiR inhibitors rescued expression of IFNAR1 and amplified the antiviral response to type I IFN, resulting in decreased viral load. Based on these data and our previous observation that inhibition of myomiRs rescues expression of IFNL2 and the risk allele of IFNL3 during HCV infection, myomiR inhibition could aid in a multistep fashion by increasing both hepatocyte production of type III IFNs and responsiveness to pegIFN-α. This would be particularly relevant during IFN-based therapies, considering that we found that type I IFNs increase myosin/myomiR expression (Fig. 4). The ability of type I IFNs to amplify myosin expression, a surrogate readout for myomiR expression, is also interesting in terms of type I IFN signaling feedback. myomiRs may function to blunt the cellular response to secondary type I IFN signaling, including the production of type III IFNs, which can be induced by prolonged type I IFN stimulation38 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

It is remarkable that unlike treatment with type I IFNs, treatment of HCV-infected hepatocytes with type III IFNs did not induce myosin/myomiR expression, raising the possibility that type III IFN-based therapies will bypass IFN induction of these myomiRs. Currently, IFN-λ-based therapy is in phase 3 clinical trials, and results from phase 2 trials have shown it to be as effective as pegIFN-α with fewer adverse effects; this suggests that IFN-λ may be a viable replacement for pegIFN-α39,40. myomiR inhibition may also benefit patients on IFN-free DAA regimens by increasing endogenous type III IFN production and type I IFN signaling. Taking these results together with our previous finding that these myomiRs also target IFNL2 and the risk variant of IFNL3, we conclude that myomiRs suppress both type I and type III IFN signaling during HCV infection. Collectively, these data add to our understanding of HCV immune evasion strategies and cross-talk between type I and type III IFN signaling pathways.

ONLINE METHODS

Cell culture conditions

HepG2 and PH5CH8 cell lines were obtained from ATCC. The identity of each hepatocyte cell line was confirmed based on their response to stimuli, and all cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma contamination. HepG2, Huh7, Huh7.5, PH5CH8 cells were cultured in complete DMEM (Sigma) media containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (Mediatech). HepG2 cells overexpressing miR-208b (pLV-miR-208b), miR-499a-5p (pLV-miR-499a-5p), or a non-targeting control miRNA were cultured in complete DMEM with 2 μg/mL puromycin dihydrochloride. Huh7-K2040, Huh7-HP and Huh7-JFH1 replicon cells were cultured in DMEM with 2 μg/mL G418, 1mM sodium pyruvate, 1× MEM NEAA, 2mM L-Glutamine, and 10% FBS (Hyclone, no heat inactivation). All cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

IFNLR1 knockout with CRISPR–Cas9 system

IFNLR1 guide RNA (gRNA, 5′-GCTCTCCCACCCGTAGACGG-3′) was cloned downstream of the U6 promoter in the pRRL-U6-empty-gRNA-MND-Cas9-t2A-Puro vector using In-Fusion enzyme mix (Clontech). To generate knock out of IFNLR1 in Huh7, cells were transfected with either cas9 alone or IFNLR1 gRNA-Cas9 plasmids. For transfection of CRISPR–cas9 plasmids, 3 × 106 cells were seeded onto a 10 cm dish the day before transfection. 10 μg of either cas9 alone or IFNLR1 gRNA-cas9 was transfected using the CaPO4 transfection kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 48 h post transfection, 2 μg /mL of puromycin was added to the media and cells were cultured for an additional week under selection before transduction efficiency was accessed. To confirm successful gene targeting in selected cells, genomic DNA was extracted from Huh7-wt/cas9 and Huh7-IFNLR1−/− cells (NucleoSpin Tissue; Clontech). The genomic region surrounding the IFNLR1 target site was amplified by PCR, forward 5′-GGTCCCAAAGCTAGGGAGGG-3′ and reverse 5′-TTGTTGTACAGGTC CTGTTTCTTCAGG-3′. PCR products were evaluated by restriction fragment length polymorphism using the enzyme Hyp166II, the restriction site of which overlaps the IFNLR1 CRISPR targeting site.

RNA isolation, reverse transcription and quantification of gene expression

RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) or by using the TRIzol method (Qiagen). qPCR was carried out using the QuantiTect RT kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR was carried out using the ViiA7 qPCR system with TaqMan reagents (Life Technologies). Gene expression levels were normalized to HPRT for all cell types.

Total RNA for miRNA analysis was extracted with miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) or by using the Trizol method. miRNA-RT was carried out using miRCURY LNA Universal RT according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Exiqon), and SYBR qPCR master mix (Life Technologies) was used for quantitative PCR. Three LNA primers (Exiqon) designed to detect the most common miR-499a-5p isomiRs (miRBase) were pooled for detection. The miR-208b LNA primer was optimized by using a primer with a lower Tm. SNORD38B was used as an endogenous control.

miRNA mimic and inhibitor transfections and stimulations

miR-208b mimic, miR-499a-5p mimic, as well as a non-targeting control (NC) mimic that does not bind to any known mammalian genes, were purchased from Dharmacon. As commercially available inhibitors of miR-208b and miR-499a-5p (Dharmacon) had marginal efficacy of 40% in our systems, we developed LNA inhibitors specific for either miR-208b or miR-499a-5p. These custom LNA inhibitors showed a consistent 80% inhibition of their target miRNA4. A LNA inhibitor control in which the seed sequence of miR-499a-5p was mutated and predicted to bind no known human miRNA was used as a non-targeting control (NC). For transfection of mimics/inhibitors, cells were seeded at a density of 2–3 × 105 cells/well of a 6-well plate, and 20–40 nM/well of mimics or inhibitors were transfected using 5–10 μl/well of DharmaFECT 4 transfection reagent (Dharmacon).

For all stimulations done on mimic- or inhibitor-transfected cells, 500 IU/mL of human IFN-β was used. For immunoblot analysis of HepG2 cells, cells were stimulated 48 h post-transfection with mimics and whole-cell extracts were collected at 0, 15, 30, and 60 min. For ISG expression in HCV-infected Huh7 cells or mimic-transfected HepG2 cells, cells were stimulated 48 h post transfection with inhibitors/mimics and for the HCV-infected cells, 36 h post infection. IFN-α and IFN-β were purchased from PBL, and IFN-λ1, IFN-λ2 and IFN-λ3 were purchased from R&D Systems.

mRNA stability

Mimic-transfected HepG2 cells were treated with 10 μg/106 cells/mL of Actinomycin D 48 h post transfection. Samples were taken at 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8 h post-treatment and processed for qPCR analysis. HepG2 cells treated with ActD did not show any overt toxicity at the specified concentration at 8 h.

Immunoblot analysis

30–60 μg of lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Thermo Scientific). The membranes were then probed using the recommended antibody dilution in 5% BSA in TBST (Tris-Buffered Saline and Tween 20) or 5% non-fat milk in TBST for phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701), STAT1, phospho-STAT2 (Tyr690), STAT2, phospho-Tyk2 (Tyr1054/1055), Tyk2, phospho-Jak1 (Tyr1022/1023), Jak1 or β-actin (13E5) (Cell Signaling). Validation of antibodies is provided on the manufacturer’s website.

HCV infection

Cell culture-adapted HCV JFH1 genotype 2A strain was propagated and infectivity titrated, as previously described previously39. For HCV infections, inhibitor-transfected cells were inoculated with virus at a Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) of 1.0 for 3 h and then the media was replaced. Cells were harvested using Trizol or RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen) at the indicated times. HCV RNA copy number was measured using quantitative qPCR with the TaqMan Fast Virus 1-step kit and primers specific for the 5′ UTR (Pa03453408_s1, Life Technologies). The copy number was calculated by comparison to a standard curve of in vitro-transcribed full-length HCV RNA (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

HCV RNA transcription and transfections

Plasmids containing full-length cDNA sequences of JFH1, JC1 or H77D HCV viruses were linearized by restriction enzyme digest and purified. The linearized product was used for in vitro transcription using the T7 MEGAscript kit (Life technologies). Following transcription, samples were DNAse treated, unincorporated nucleotides were removed and the resulting RNA sample was run on a 1% formaldehyde gel to check for purity. For HCV RNA transfection, PH5CH8 cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well in a 12 well plate. The next day 200 ng of HCV RNA was transfected per well using 1.125 μl mRNA Boost reagent (Mirus) and 2.25 μl TransIT-mRNA reagent (Mirus)41. Cells were harvested 48 h post transfection.

HCV viral titer

HCV viral titer was measured using a focus-forming unit (FFU) assay where 100 μl of cell supernatant was serially diluted 10 to 100-fold in complete DMEM and used to infect 8 × 104 Huh-7.5 cells per well in 24 well plates. Cells incubated for 2 h, then supernatant was removed and cells were washed twice with PBS and supplemented with complete DMEM. 48 h post-inoculum cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and incubated with an anti-HCV NS5A antibody, then the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary. VECTOR VIP Peroxidase Substrate Kit (SK-4600) was used to visualize staining, and focal units were counted and expressed as FFU/mL of supernatant.

Statistical analysis

Unpaired Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 6 Software. For samples with unequal variance, determined by F-test, Welch’s correction was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. was used for statistical analyses of experiments with technical replicates noted in figure legends. For data using pooled biological replicates, the averages of technical replicates from each biological replicate were pooled and used for statistical analyses and described in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded partly by the Department of Immunology, Royalty Research Fund, University of Washington (R.S.) and by National Institutes of Health grants AI108765 (R.S.), AI060389, AI40035 (M.G.), and CA148068 (C.H.H.). This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E (M.C.). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government. This Research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Frederick National Lab, and Center for Cancer Research. We thank S. Lemon and C. Rice for generously providing the H77D and JC1 viral strains, respectively; Y. Loo, S. Ozarkar and L. Kropp for experimental support; and C. Lim, A. Stone and the Gale and Savan labs for the discussions and feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.J., A.P.M., and R.S. designed the study. A.J. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. R.S. directed the study. A.J., A.P.M., J.S., R.C.J. and M.H. performed experiments. A.J., S.M.H., A.K. and S.B. performed infections and flow cytometry preparations. D.P.B. provided reagents and reviewed the manuscript. D.P.B. was an employee of Biogen Idec and owns company stock. C.H.H., M.C. and M.G. provided intellectual input.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare competing financial interests: details are available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–1273.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavanchy D. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558–567. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McFarland AP, et al. The favorable IFNL3 genotype escapes mRNA decay mediated by AU-rich elements and hepatitis C virus-induced microRNAs. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:72–79. doi: 10.1038/ni.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang TJ, Ghany MG. Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1907–1917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1213651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manns MP, von Hahn T. Novel therapies for hepatitis C—one pill fits all? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:595–610. doi: 10.1038/nrd4050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54:1433–1444. doi: 10.1002/hep.24641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawitz E, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1878–1887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afdhal N, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1889–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawlotsky JM. New hepatitis C therapies: the toolbox, strategies, and challenges. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1176–1192. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayasekera CR, Barry M, Roberts LR, Nguyen MH. Treating hepatitis C in lower-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1869–1871. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1400160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearlman BL. Protease inhibitors for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype-1 infection: the new standard of care. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:717–728. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schinazi R, Halfon P, Marcellin P, Asselah T. HCV direct-acting antiviral agents: the best interferon-free combinations. Liver Int. 2014;34(Suppl 1):69–78. doi: 10.1111/liv.12423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rauch A, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment failure: a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1338–1345. 1345.e1–1345.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas DL, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ge D, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suppiah V, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka Y, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Castellarnau M, et al. Deciphering the interleukin 28B variants that better predict response to pegylated interferon-α and ribavirin therapy in HCV/HIV-1 coinfected patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.di Iulio J, et al. Estimating the net contribution of interleukin-28B variation to spontaneous hepatitis C virus clearance. Hepatology. 2011;53:1446–1454. doi: 10.1002/hep.24263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedergnana V, et al. Analysis of IL28B variants in an Egyptian population defines the 20 kilobases minimal region involved in spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prokunina-Olsson L, et al. A variant upstream of IFNL3 (IL28B) creating a new interferon gene IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nat Genet. 2013;45:164–171. doi: 10.1038/ng.2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheahan T, et al. Interferon lambda alleles predict innate antiviral immune responses and hepatitis C virus permissiveness. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honda M, et al. Hepatic ISG expression is associated with genetic variation in interleukin 28B and the outcome of IFN therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:499–509. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He XS, et al. Global transcriptional response to interferon is a determinant of HCV treatment outcome and is modified by race. Hepatology. 2006;44:352–359. doi: 10.1002/hep.21267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welzel TM, et al. Variants in interferon-alpha pathway genes and response to pegylated interferon-Alpha2a plus ribavirin for treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the hepatitis C antiviral long-term treatment against cirrhosis trial. Hepatology. 2009;49:1847–1858. doi: 10.1002/hep.22877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukuda R, et al. Expression of interferon-alpha receptor mRNA in the liver in chronic liver diseases associated with hepatitis C virus: relation to effectiveness of interferon therapy. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:806–811. doi: 10.1007/BF02358606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukuda R, et al. Effectiveness of interferon-alpha therapy in chronic hepatitis C is associated with the amount of interferon-alpha receptor mRNA in the liver. J Hepatol. 1997;26:455–461. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathai J, et al. IFN-alpha receptor mRNA expression in a United States sample with predominantly genotype 1a/I chronic hepatitis C liver biopsies correlates with response to IFN therapy. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:1011–1018. doi: 10.1089/107999099313226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morita K, et al. Expression of interferon receptor genes in the liver as a predictor of interferon response in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1999;58:359–365. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199908)58:4<359::aid-jmv7>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morita K, et al. Expression of interferon receptor genes (IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 mRNA) in the liver may predict outcome after interferon therapy in patients with chronic genotype 2a or 2b hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;26:135–140. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, et al. Virus-induced unfolded protein response attenuates antiviral defenses via phosphorylation-dependent degradation of the type I interferon receptor. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandra PK, et al. HCV infection selectively impairs type I but not type III IFN signaling. Am J Pathos. 2014;184:214–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwerk J, Jarret AP, Joslyn RC, Savan R. Landscape of post-transcriptional gene regulation during hepatitis C virus infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;12:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Rooij E, et al. A family of microRNAs encoded by myosin genes governs myosin expression and muscle performance. Dev Cell. 2009;17:662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu S, et al. Measuring antiviral activity of benzimidazole molecules that alter IRES RNA structure with an infectious hepatitis C virus chimera expressing Renilla luciferase. Antiviral Res. 2011;89:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eldrup AB, et al. Structure-activity relationship of heterobase-modified 2′-C-methyl ribonucleosides as inhibitors of hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5284–5297. doi: 10.1021/jm040068f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ank N, et al. Lambda interferon (IFN-lambda), a type III IFN, is induced by viruses and IFNs and displays potent antiviral activity against select virus infections in vivo. J Virol. 2006;80:4501–4509. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4501-4509.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeuzem S, et al. Pegylated Interferon-Lambda (PEGIFN-L) shows superior viral response with improved safety and toleraility versus PEGIFNa-2A in HCV patients (G1/2/3/4): Emerage phase IIB through week 12. J Hepatol. 2011;54:S538–S539. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muir AJ, et al. A randomized phase 2b study of peginterferon lambda-1a for the treatment of chronic HCV infection. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1238–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzalez G, Pfannes L, Brazas R, Striker R. Selection of an optimal RNA transfection reagent and comparison to electroporation for the delivery of viral RNA. J Virol Methods. 2007;145:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.