Abstract

Methyl groups are very useful probes of structure, dynamics and interactions in protein NMR spectroscopy. In particular, methyl-directed experiments provide high sensitivity even in very large proteins, such as membrane proteins in a membrane-mimicking environment. In this chapter we discuss the approach for labelling methyl groups in E. coli based protein expression, as exemplified with the mitochondrial carrier GGC.

Keywords: NMR spectroscopy, methyl labelling, refolding, deuteration, detergent

1. Introduction

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a versatile tool for studying the structure, dynamics and interactions of biomolecules at atomic resolution. Over the last decades, biological NMR spectroscopy constantly progressed towards more complex and larger molecules. This evolution was triggered by developments in NMR technology in terms of spectroscopic approaches and sample preparation. In particular, the specific introduction of [1H, 13C]-labelled methyl groups in a perdeuterated environment is a key element that has allowed NMR to study large molecule systems and complexes (1). Large molecules are inherently very difficult to study by solution-state NMR, because the slow overall reorientation leads to fast decay of NMR signals, and thus low sensitivity and resolution. Due to the rapid rotation of methyl groups (on a picosecond time scale), the methyl group is partly decoupled from the slow overall tumbling. Therefore, methyl groups have very favourable spectroscopic properties even in large molecules, in particular when the surrounding is deuterated. Sensitivity of methyl groups is also enhanced by the three-fold proton multiplicity. Methyl labelling techniques combined with appropriate spectroscopic approaches (in particular, methyl-TROSY experiments (2)) have been shown to provide insight into molecules of up to about 1 MDa in size (3). Methyl labelling protocols are based on the incorporation of specific precursors during the expression in bacteria growth. Labelling protocols for the methyl groups of all methyl-bearing amino acids have been developed over the last two decades, ensuring that the desired methyl group is labelled at high yield and specificity without scrambling of the introduced isotopes to other sites in the protein (see Table 1). More and more laboratories are using these labelling protocols because most of the precursors can be prepared directly in the laboratory. However, to simplify the use of these protocols, precursors are now commercially available with different isotopic labelling scheme used for different types of NMR studies (4, 5). Other precursors targeting aromatic residues (Trp, Phe, Tyr), have been introduced to label the side-chain of these residues. These labelling approaches of sites other than methyl groups are not within the scope of this review; the reader is directed towards references listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Precursors for 13CH3 group labelling

| Name of the precursors | Amino Acids | Methyl groups | Quantity (mg.L-1) | Scrambling suppression a | Quantity (mg.L-1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Alanine | Ala | β | 600 | 2-ketoisovalerate isoleucine succinate glycerol |

200 60 2500 2500 |

(20) |

| L-Threonine | Thr | γ2 | 50 | Ketobutyrate glycine |

50 100 |

(21) |

| L-Methionine | Met | ε | 250 | (22) | ||

| 4-Methyl-thio-2-ketobutyrate | Met | ε | 100 | (23) | ||

| 2-Ketobutyrate | lle | δ1 | 60 | (18) | ||

| 2-(S)-hydroxy-2-ethyl-3-ketobutyrate | lle | δ1 | 60 | (24) | ||

| 2-Hydroxy-2-ethyl-3-ketobutyrate* | lle | γ2 | 140 | 2-ketoisovalerate | 200 | (25) |

| 2-Hydroxy-2-ethyl-3-ketobutyrate* | lle | γ2 | 100 | 2-ketoisovalerate | 200 | (26) |

| 2-Ketoisocaproate | Leu | δ1/δ2 | 150 | (27) | ||

| Stereospecifically labeled L-Leucine | Leu | δpro-S | 20 | (28) | ||

| 2-Acetolactate | Val | γpro-S | 300 | L-Leucine | 20 | (29) |

| Stereospecifically labeled Valine | Val | γpro-S | 100 | L-Leucine | 20 | (28) |

| 2-Ketoisovalerate | Leu/Val | δ1/δ2 γ1/γ2 |

100-200 | (30) (31) | ||

| 2-Acetolactate | Leu/Val | δ/γpro-S | 300 | (19) |

Scrambling suppressed by co-addition of U-[D] of the different compounds.

Table 2.

Precursors for Aromatic group labeling

The six naturally methyl-bearing amino acids (Ala, Leu, Val, Ile, Thr, Met) represent about ~35 % of the amino acids in soluble proteins, and up to 45 % in α-helical membrane protein. Methyl groups, therefore, provide a good coverage across the structure of membrane proteins, and are in principle a good source of information of structure (through intra- and intermolecular spin-spin couplings, manifest as nuclear Overhauser effect, NOEs), dynamics and interactions. The potential of methyl-directed NMR applied to membrane proteins is, however, somewhat compromised by the fact that methyls tend to point towards the hydrophobic membrane-mimicking environment (detergent, lipids). Consequently, their chemical shifts tend to be similar, resulting in narrower dispersion of methyl signals and difficulty of resonance assignment. Nonetheless, multiple NMR studies of membrane proteins show the power of the strategy, such as studies of structure and dynamics of the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) (6), the prokaryotic pH-dependent potassium channel (KcsA) (7), the hexameric p7 cation channel from hepatitis C virus (8) and the phototaxis receptor sensory rhodopsin II (PSRII) (9). Methyl labelling is also becoming an increasingly useful tool for proton-detected MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopy (10–12), and although it has to our knowledge so far not been applied to membrane proteins, the approach will certainly rapidly gain popularity also in this field.

This chapter highlights a methyl-specific isotope labelling scheme to study membrane proteins. We outline the approach to produce, purify and assign the methyl groups of GTP/GDP carrier (GGC) from yeast mitochondria in detergent micelles (13). GGC is a member of the mitochondrial carrier family (14). These carriers catalyse the transport of small solutes across the inner mitochondrial membrane. GGC transports external GTP into the mitochondrial matrix while exporting internal GDP out of the matrix (14). When refolded in detergent micelle, GGC forms a highly dynamic ensemble, discussed previously (13).

2. Materials

2.1. Precursor Preparation, Bacterial Expression & Isotope labelling

Lysogeny Broth (LB) agar plates (Miller): Dissolve 40 g of LB agar (Miller) in 1 L of distilled water and in a 2-L flask. Cover with foil and autoclave. Monitor the temperature as it cools. When the temperature reaches ~50°C, add 1 mL of the antibiotic stock solution 1000x (ex 100 μg.L-1 for ampicillin). Pour ~15 mL into plate, let the LB agar solidify at room temperature, place into a plastic bag, seal with tape, and store at 4°C.

LB medium (Miller): Dissolve 25 g of powdered LB medium in 1 L of distilled water. Adjust the pH to 7.4 if necessary using NaOH. Autoclave and store at room temperature. Add antibiotics prior to use.

M9 salts: For 1 L of growth medium, 6 g of anyhydrous Na2HPO4, 3 g of anhydrous KH2PO4, 0.5 g of NaCl, 1 g of NH4Cl. The salts are first dissolved in distilled and 0.22-μm filtered H2O and autoclaved (M9H). For deuteration, the salts are dissolved in 99.8% D2O and sterile filtered through 0.22-μm filter flasks, rather than autoclaved (M9D).

Oligo-elements stock solution: Prepare a 1 M solution of MgSO4, a 0.1 M solution of CaCl2, a 0.1 M solution of MnSO4, a 50 mM solution of ZnCl2, a 50 mM solution of FeCl3. Sterilize on 0.22-μm filter flasks and store at 4°C. Stocks solutions should be prepared in H2O when used in M9H medium or in D2O when used in M9D medium.

100x MEM Vitamin solution (Sigma-Aldrich): store 10 mL aliquots at −20°C.

Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG): Prepare a 0.5 M solution using distilled water. Syringe filter and store 1 mL aliquots at −20°C.

40% D-glucose: Dissolve 40 g of D-glucose in 100 mL distilled water. Sterilize by filtration and store at room temperature.

M9H medium: For 1 L of M9 salts, add 5 mL of 40% D-glucose, 1 mL of 1 M MgSO4, 1 mL of 0.1 M CaCl2, 1 mL of 0.1 M MnSO4, 1 mL of 50 mM ZnCl2, 1 mL of 50 mM FeCl3 and 10 mL of 100x MEM Vitamin solution and swirl the flask after each addition. Add antibiotics prior to use.

M9D medium: For 1 L of M9D salts, add 2 g of D-glucose, 1 mL of 1 M MgSO4, 1 mL of 0.1 M CaCl2, 1 mL of 0.1 M MnSO4, 1 mL of 50 mM ZnCl2, 1 mL of 50 mM FeCl3 and 10 mL of 100x MEM Vitamin solution and swirl the flask after each addition. Add antibiotics prior to use.

For production of 15N-labelled protein: NH4Cl is substituted by ammonium chloride (15N ≥ 99%).

For production of 13C-labelled protein: D-glucose is substituted by D-(13C)-glucose (13C ≥ 99%). For perdeuteration, D-(2H, 13C)-glucose (2H ≥ 98% ; 13C ≥ 99%) is substituted (see Note 1).

For production of methyl-specifically labelled protein: D-glucose is substituted by D-(2H, 12C)-glucose (2H ≥ 98%) and the addition of 13CH3-methyl specifically labelled precursors (see Note 2).

13CH3-methyl specifically labelled precursors: 2H-13CH3-Alanine (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 98%), 2H-13CH3-2-ketobutyric acid (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 98%), 2H-13CH3-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-3-oxo-4-butanoic acid (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 95%), 2H-L-Isoleucine (2H ≥ 98%). Specifically labelled precursors are commercially available on a deuterated form ready for direct introduction into the culture medium (NMR-Bio) or can be prepare in the laboratory (see Note 3).

Innova® 43 Incubator Shaker (Eppendorf).

2.2. In Vitro Refolding and Protein Purification

Lysis buffer: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), 100 μg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 100 μg/mL benzamidine and 5 μg/mL leupeptine.

Denaturing buffer: 3 M guanidine HCl, 1% Triton X-100, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM BME.

Refolding buffer: 0.1% Triton X-100, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM BME.

Purification buffer: 0.1% n-dodecylphosphocholine (DPC, Anatrace), 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM BME.

Gel-filtration buffer: 0.1% DPC, 50 mM MES, pH 6.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM BME, and it is filtered on a 0.22-μm polyethersulfone membrane (Millipore).

NMR buffer: 0.1% DPC, 50 mM MES, pH 6.0, 1 mM BME, and 5-10% D2O, used for spectrometer lock.

NuPage Novex Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen).

4x NuPAGE® LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen).

NuPAGE® MES SDS running buffer (Invitrogen).

Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen).

Refrigerated Akta FPLC purification system and accessories equipped with HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 PG (GE Healthcare).

Dialysis cassette: 10 kDa MWCO (Thermo Fischer).

Centrifugal concentrator: 10 kDa MWCO (Millipore).

Shigemi NMR tubes susceptibility matched to D2O (Shigemi Inc).

2.3. Solution-State NMR Spectroscopy Experiments for Resonance Assignment and Chemical Shift Perturbation Studies

3. Methods

3.1. Precursors Preparation, Bacterial Expression & Isotope labelling

3.1.1. Uniform (2H, 13C, 15N)

The gene of interest was inserted between the NdeI (5’) and XhoI (3’) sites in the pET-21a (+) plasmid which contains a C-terminus (His)6-tag.

Transform the plasmid (17) into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, plate on LB agar containing ampicillin and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Pick a freshly transformed colony of BL21(DE3) cells and inoculate 5 mL LB medium in a shaking incubator (220 rpm) at 37°C during 4 h. (final OD600 is about 1.0).

Inoculate with previous LB culture, 50 mL of M9H medium to achieve a starting OD600 of 0.1. Incubate the culture in a shaking incubator (220 rpm) at 37°C during 4 h. (final OD600 is about 0.8).

Spin down the cells at 2,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature and resuspend a small amount of them in 100 mL of M9D medium to achieve a starting OD600 of 0.1. Incubate the culture in a shaking incubator (220 rpm) at 37°C during overnight. (final OD600 is about 1.5) (see Note 4).

Inoculate with overnight culture, 900 mL of M9D medium in a 3 L baffled flask to achieve a starting OD600 of 0.1 (see Note 5). Incubate the culture in a shaking incubator (220 rpm) at 37°C until the cultures reaches an OD600 of 0.6 (see Note 6).

Induce expression of the protein by adding 1 mL of IPTG to a final concentration of 0.5 mM at 37°C for 4 h. the final OD600 is typically between 1.2 and 1.4 (see Note 6, note 7).

Harvest the cells by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Resuspend the cells with lysis buffer in 50 mL falcon tube and freeze the cells at -80°C.

3.1.2. Methyl Specific Labelling (2H, 13C, 15N)

Use uniform (2H, 13C, 15N) labelling protocol described above until step 6.

Inoculate with overnight culture, 700 mL of M9D medium in a 3 L baffled flask to achieve a starting OD600 above 0.1 (see Note 5). Incubate the culture in a shaking incubator (220 rpm) at 37°C until the cultures reaches an OD600 of 0.6.

-

Add the precursors diluted in 200 mL of M9D medium (see Note 8).

-

(a)

[U-2H], I-[13CH3]δ1-GGC: 60 mg/L of 2H-13CH3-2-ketobutyric acid (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 98%).

-

(b)

[U-2H], A-[13CH3]β, L-[13CH3]proS, V-[13CH3]proS-labelled protein: 700 mg/L of 2H-13CH3-Alanine (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 98%), 300 mg/L of 2H-13CH3-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-3-oxo-4-butanoic acid (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 95%) and 60 mg/L of 2H-L-Isoleucine (2H ≥ 98%).

-

(a)

Let the culture grow for 1 h (OD600 reaches the value of 0.6)(see Note 6).

Induce expression of the protein by adding 1 mL of IPTG to a final concentration of 0.5 mM at 37°C for 4 h. The final OD600 is typically between 1.2 and 1.4 (see Note 6, Note 7, Note 9).

Harvest the cells by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Resuspend the cells with lysis buffer in 50 mL falcon tube and freeze the cells at -80°C.

3.2. In Vitro Refolding and Protein Purification

Resuspend the cell pellets in 100 mL lysis buffer per liter growth using a Dounce homogenizer. Disrupt the cells by sonication on ice, until obtaining a clear and homogeneous suspension (3x 4 min, at 50 W using 50% duty cycle). Spin down E. coli inclusion bodies at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to purify away water-soluble contaminants.

Solubilise the GGC-containing inclusion bodies in 50 mL of denaturing buffer and incubate under vigorous stirring at 4°C overnight. Pellet undissolved matter by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C.

Equilibrate 10 mL per liter of growth of Ni-NTA agarose beads on column with 3 column volumes (CVs) of denaturing buffer.

Add 10 mM imidazole to the supernatant and load onto equilibrated Ni-NTA column at 1 – 2 mL/min.

Wash with 3 CVs of denaturing buffer containing 10 mM imidazole to remove contaminant proteins.

Wash with 3 CVs of refolding buffer (see Note 10).

Wash with 3 CVs of purification buffer (see Note 11).

Elute bound GGC with 3 CVs of purification buffer containing 250 mM imidazole.

Pre-rinse centrifugal concentrators (10 kDa MWCO) with purification buffer at 3,200 × g for 5 min. Concentrate the protein to ~5 mg/mL using series of 5-min spins at 3,200 × g and 4°C.

Equilibrate the HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 PG column with 1.5 CVs of filtered gel-filtration buffer.

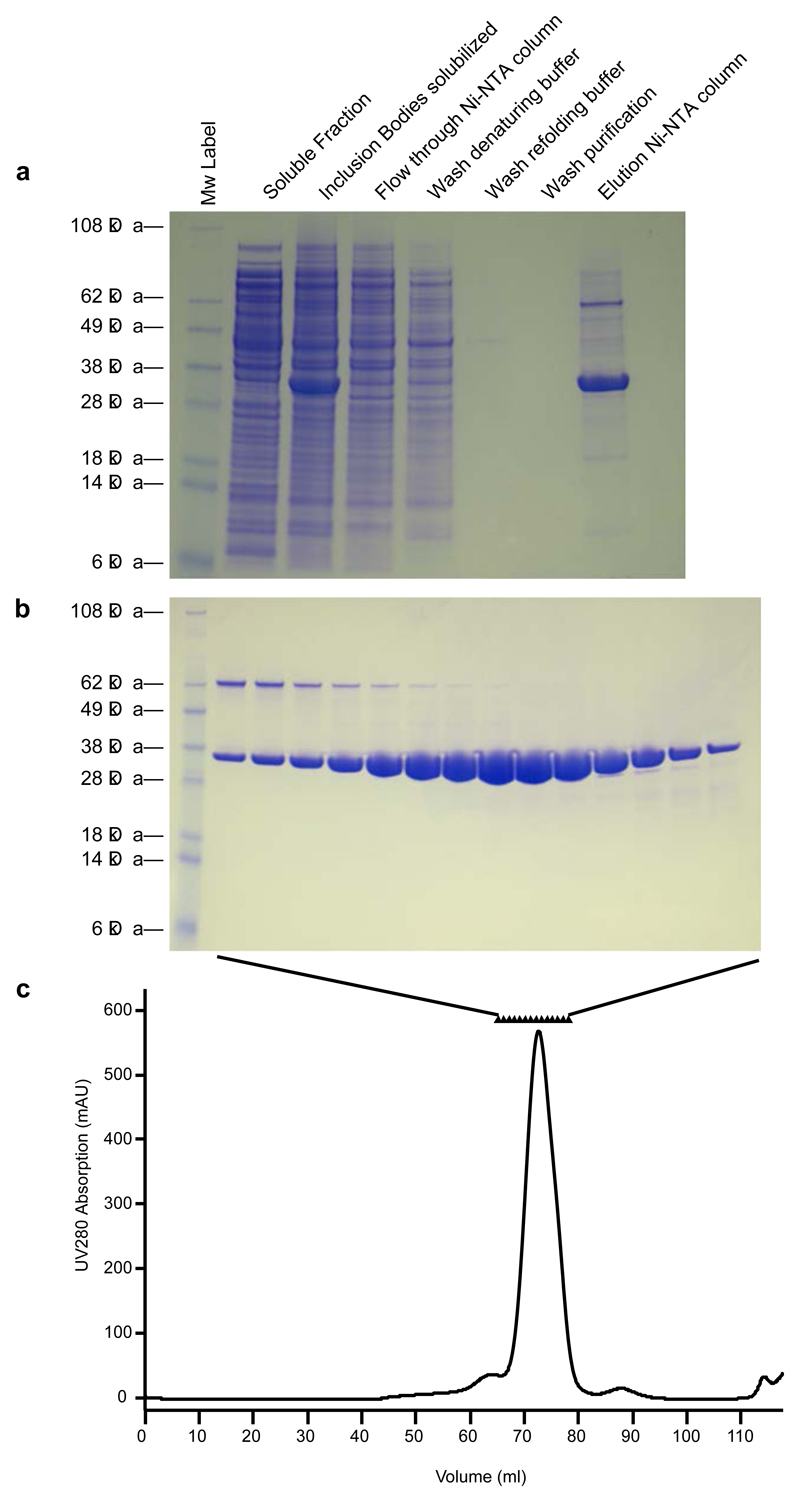

Load onto the gel filtration column at 1.0 mL/min, collecting 0.5 mL fractions for 1.5 CVs. Assess the purity of relevant fractions by SDS-PAGE (5 μL of each fraction). (Fig. 1)

Pool the pure protein fractions and dialyse for 2 h against NMR buffer using dialysis cassette (10 kDa MWCO), twice. Measure protein concentration by UV absorbance.

Pre-rinse centrifugal concentrators (10 kDa MWCO) with NMR buffer at 3,200 × g for 5 min. Concentrate the protein to 0.5-1.0 mM using series of 5-min spins at 3,200 × g and 4°C. Load the final sample to a Shigemi NMR tube.

Figure 1. Purification of GGC.

(a) Different biochemical steps were analysed by SDS-PAGE. (b) SDS-PAGE of fractions from size-exclusion chromatography. (c) Typical Size exclusion chromatography of GGC in DPC.

3.3. Solution-State NMR Spectroscopy Experiments for Resonance Assignment and Chemical Shift Perturbation Studies

3.3.1. Sequence-Specific Assignment of Backbone

To achieve nearly complete sequence-specific backbone chemical shift assignment of 1HN, 15N, 13Cα, 13Cβ and 13C’ use the TROSY versions of HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCACB, HN(CO)CACB, HN(CA)CO, HNCO (ref). In combination, a 3D (HN,HN)-HMQC-NOESY-TROSY with 15N, 15N and 1HN evolution in the t1, t2 and t3 dimensions, respectively was recorded on 0.9 mM U-[2H, 13C,15N]-GGC.

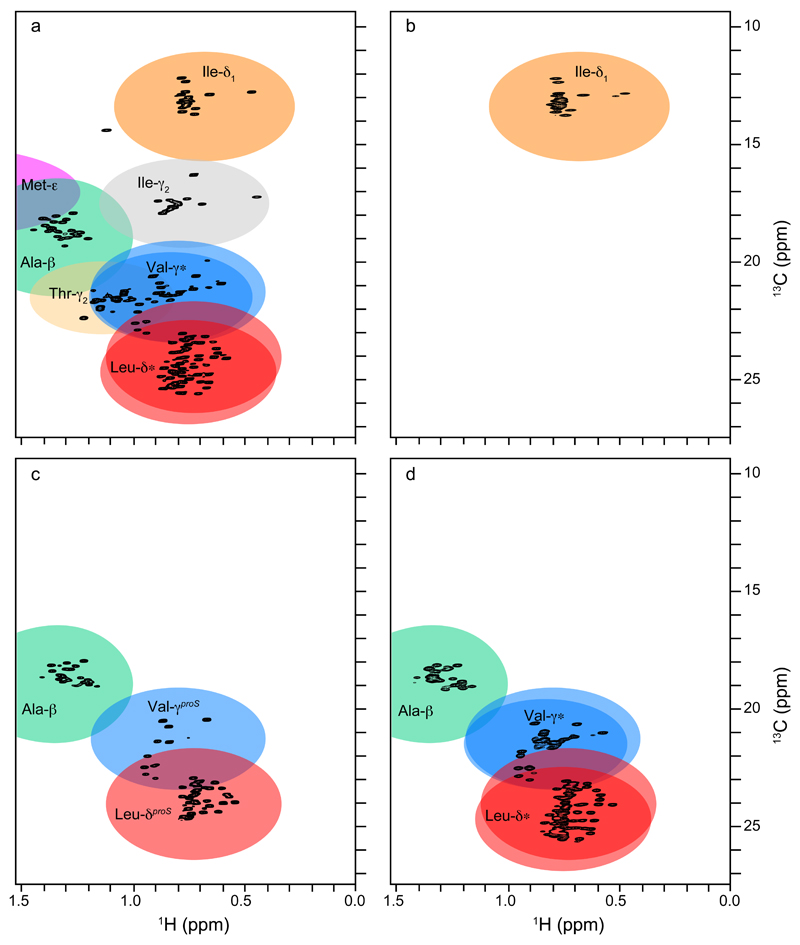

Process spectra, for example using the software NMRPipe (15) and assign resonances, e.g. in the software CCPNMR (16). (Fig. 2)

Figure 2. Examples of specific methyl-labelling of GGC.

(a) 2D (1H,13C)-CT-HSQC of U-[13C, 15N]-GGC. Location of different methyl groups is highlighted by coloured ellipses, two ellipses are shown for racemic methyl groups of Leu and Val. 2D (1H,13C)-HMQC of (b) U-[D, 15N],(Ile-δ1)-[13CH3], (c) U-[D,15N],(Ala-β, Leu/ValproS)-[13CH3] or (d) U-[D, 15N],(Ala-β)-[13CH3]-(Leu/Val)-[13CH3,12CD3]-labelled GGC.

3.3.2. Methyl Group Assignment

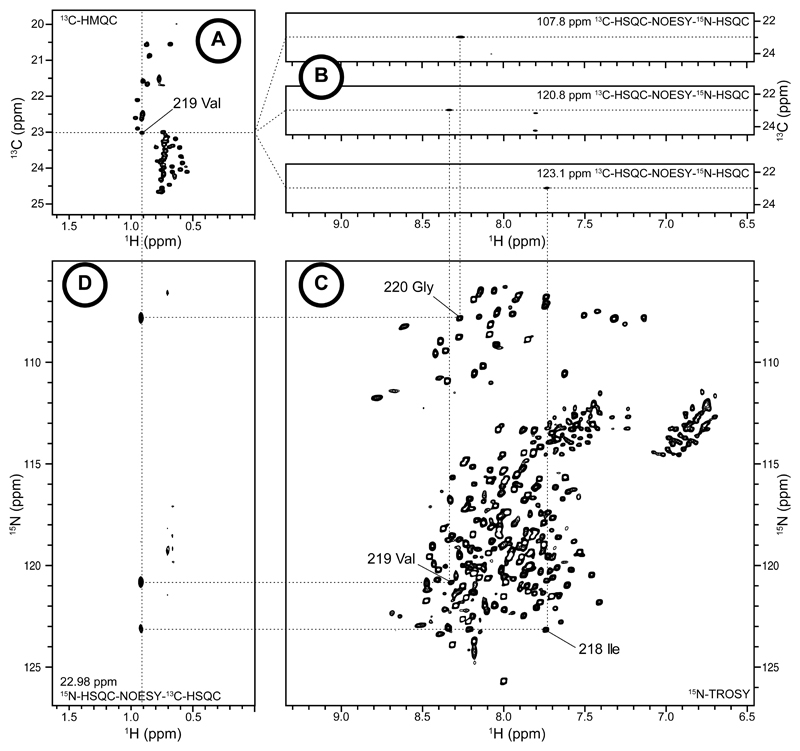

To assign methyl groups, one 15N-TROSY-HSQC, one 13C-HMQC and two 3D NOESY experiments 13C-HSQC-NOESY-15N-HSQC (CN-NOESY, 350 ms) and 15N-HSQC-NOESY-13C-HSQC (NC-NOESY, 420 ms) are recorded for each labelled samples (Fig. 3).

Start from a methyl group resonance (Fig. 3 A) and navigate in the CN-NOESY spectrum to find all cross-peaks corresponding to magnetization transfer from the methyl group to assign (Fig. 3 B). Then for each possible amide resonances (Fig. 3 C), navigate in the NC-NOESY spectrum to find cross-peaks corresponding to the methyl group resonance (Fig. 3 D).

Get the proton and nitrogen frequencies from CN-NOESY and NC-spectrum, respectively.

Assign the methyl group from neighbouring amide resonances found.

Repeat the process for each methyl group resonance (see Note 12).

Figure 3. Approach for methyl assignment.

(a) (c) 2D (1H,13C)-HMQC and (1H,15N)-TROSY of U-[D, 15N],(Ala-β, Leu/ValproS)-[13CH3]-labelled GGC. (b) Strips extract from 3D CNH-NOESY spectrum of cross-peaks corresponding to magnetization transfer from the methyl group 219 ValproS. (d) Section of 2D slice from 3D NCH-NOESY spectrum at carbon methyl resonance of 219 ValproS.

4. Notes

D-(2H, 13C)-glucose (2H ≥ 98% ; 13C ≥ 99%) should be used when uniform 13C labelling is desired for backbone assignment or in the context of methyl assignment with magnetization transfer from methyl to backbone. Also, uniformly 13C-labelled precursors must be used.

D-(2H, 12C)-glucose (2H ≥ 98%) should be used when best sensitivity and resolution is desired. Such sample can be used for chemical shift perturbation studies with 1H-13C-HMQC experiments without the use of constant time, NOESY experiments and can also be used for relaxation experiments.

Precursors can be purchased in protonated form and dissolved in D2O for exchange to take place. 2H-13CH3-2-ketobutyric acid (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 98%) and 2H-13CH3-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-3-oxo-4-butanoic acid (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 95%) can be prepared as described (18), (19), respectively. 2H-13CH3-Alanine (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 98%) can be prepared by using the tryptophan synthase enzyme, as described (20).

Critical step: If cultures did not reach final OD600 ≥ 1.2, abort at this step. Bacterial adaptation was not optimal.

Critical step: Starting OD600 in D2O should be always ≥ 0.1.

Analyse protein expression levels by using SDS-PAGE. Spin down cell quantities equivalent to 200 μL of OD600 = 1.0 at 12,000 × g for 2 min at room temperature and discard supernatant. Resuspend the pellet in 15 μL of 4x NuPage® LDS Sample buffer and 45 μL of H2O, sonicate and place the sample on a 90°C heat block for 5 min. Load 20 μL sample per lane and run the gel using NuPAGE® MES SDS running buffer.

Optimal temperature and IPTG conditions should be explored for each construct. In some cases, lower IPTG concentration results in higher expression levels. Lower temperature and increasing induction time results in higher expression (24 h at 18°C, or 12H at 24°C). In the case of GGC, lower the temperature lead to decrease the amount of expression.

To minimize isotope scrambling and maximize isotope incorporation add the labelled precursors to the culture one hour prior to induction. To do so, dilute the cultures with a large volume of media containing the precursors (200 mL). The cultures should reach back OD600 of 0.6 after 1h.

Critical step: Avoid excessively prolonged growth after induction to prevent isotope scrambling by precursor recycling.

In this step, we used a fast exchange by removing the guanidine HCl and decreasing the amount of detergent in one step. However, in some case a more gentle protocol can be use by successive washing of the column with solutions of decreasing concentration.

In this step, different solutions of detergent and mixture can be used to optimize the sample condition.

For the assignment of Alanine, 2H-13CH3-15N-Alanine (13C ≥ 99%; 2H ≥ 98%; 15N ≥ 98%;) must be used for labelling. In case 2H-13CH3-14N-Alanine is used, no H-N correlation peak can be observed, and consequently no methyl-backbone NOESY cross peak. In such case, the assignment of the methyl group has to rely on NOE contacts to other backbone sites.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the European Research Council (ERC-Stg-2012-311318-ProtDyn2Function). We would like to thank Pr. J. J. Chou and Dr. K. Oxenoid for stimulating discussions, and also Dr. J. Boisbouvier and Dr. R. Kerfah for helpful insights on labelling protocols.

References

- 1.Ruschak AM, Kay LE. Methyl groups as probes of supramolecular structure, dynamics and function. J Biomol NMR. 2010;46:75–87. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9376-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tugarinov V, Hwang PM, Ollerenshaw JE, Kay LE. Cross-correlated relaxation enhanced 1H-13C NMR spectroscopy of methyl groups in very high molecular weight proteins and protein complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10420–10428. doi: 10.1021/ja030153x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sprangers R, Kay LE. Quantitative dynamics and binding studies of the 20S proteasome by NMR. Nature. 2007;445:618–622. doi: 10.1038/nature05512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tugarinov V, Kanelis V, Kay LE. Isotope labeling strategies for the study of high-molecular-weight proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:749–754. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerfah R, Plevin MJ, Sounier R, Gans P, Boisbouvier J. Methyl-specific isotopic labeling: a molecular tool box for solution NMR studies of large proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;32:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiller S, Garces RG, Malia TJ, Orekhov VY, Colombini M, Wagner G. Solution structure of the integral human membrane protein VDAC-1 in detergent micelles. Science. 2008;321:1206–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.1161302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imai S, Osawa M, Takeuchi K, Shimada I. Structural basis underlying the dual gate properties of KcsA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:6216–6221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911270107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.OuYang B, Xie S, Berardi MJ, Zhao X, Dev J, Yu W, Sun B, Chou JJ. Unusual architecture of the p7 channel from hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2013;498:521–525. doi: 10.1038/nature12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gautier A, Mott HR, Bostock MJ, Kirkpatrick JP, Nietlispach D. Structure determination of the seven-helix transmembrane receptor sensory rhodopsin II by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:768–774. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schanda P, Huber M, Boisbouvier J, Meier BH, Ernst M. Solid-State NMR Measurements of Asymmetric Dipolar Couplings Provide Insight into Protein Side-Chain Motion. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2011;50:11005–11009. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal V, Xue Y, Reif B, Skrynnikov NR. Protein Side-Chain Dynamics As Observed by Solution- and Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy: A Similarity Revealed. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16611–16621. doi: 10.1021/ja804275p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreas LB, Le Marchand T, Jaudzems K, Pintacuda G. High-resolution proton-detected NMR of proteins at very fast MAS. J Magn Reson. 2015;253:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sounier R, Bellot G, Chou JJ. Mapping conformational heterogeneity of mitochondrial nucleotide transporter in uninhibited States. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:2436–2441. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vozza A, Blanco E, Palmieri L, Palmieri F. Identification of the mitochondrial GTP/GDP transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20850–20857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidman CE, Struhl K, Sheen J, Jessen T. Introduction of plasmid DNA into cells. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0108s37. Chapter 1: Unit1 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner KH, Kay LE. Production and Incorporation of 15N, 13C, 2H (1H-d1 Methyl) Isoleucine into Proteins for Multidimensional NMR Studies. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7599–7600. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gans P, Hamelin O, Sounier R, Ayala I, Dura MA, Amero CD, Noirclerc-Savoye M, Franzetti B, Plevin MJ, Boisbouvier J. Stereospecific Isotopic Labeling of Methyl Groups for NMR Spectroscopic Studies of High-Molecular-Weight Proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:1958–1962. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayala I, Sounier R, Use N, Gans P, Boisbouvier J. An efficient protocol for the complete incorporation of methyl-protonated alanine in perdeuterated protein. J Biomol NMR. 2009;43:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velyvis A, Ruschak AM, Kay LE. An economical method for production of (2)H, (13)CH3-threonine for solution NMR studies of large protein complexes: application to the 670 kDa proteasome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelis I, Bonvin A, Keramisanou D, Koukaki M, Gouridis G, Karamanou S, Economou A, Kalodimos CG. Structural basis for signal-sequence recognition by the translocase motor SecA as determined by NMR. Cell. 2007;131:756–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer M, Kloiber K, Hausler J, Ledolter K, Konrat R, Schmid W. Synthesis of a 13C-methyl-group-labeled methionine precursor as a useful tool for simplifying protein structural analysis by NMR spectroscopy. Chembiochem. 2007;8:610–612. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerfah R, Plevin MJ, Pessey O, Hamelin O, Gans P, Boisbouvier J. Scrambling free combinatorial labeling of alanine-beta, isoleucine-delta1, leucine-proS and valine-proS methyl groups for the detection of long range NOEs. J Biomol NMR. 2015;61:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s10858-014-9887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruschak AM, Velyvis A, Kay LE. A simple strategy for (1)(3)C, (1)H labeling at the Ile-gamma2 methyl position in highly deuterated proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2010;48:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayala I, Hamelin O, Amero C, Pessey O, Plevin MJ, Gans P, Boisbouvier J. An optimized isotopic labelling strategy of isoleucine-gamma(2) methyl groups for solution NMR studies of high molecular weight proteins. Chem Commun. 2012;48:1434–1436. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12932e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lichtenecker RJ, Coudevylle N, Konrat R, Schmid W. Selective isotope labelling of leucine residues by using alpha-ketoacid precursor compounds. Chembiochem. 2013;14:818–821. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyanoiri Y, Takeda M, Okuma K, Ono AM, Terauchi T, Kainosho M. Differential isotope-labeling for Leu and Val residues in a protein by E. coli cellular expression using stereo-specifically methyl labeled amino acids. J Biomol NMR. 2013;57:237–249. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9784-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mas G, Crublet E, Hamelin O, Gans P, Boisbouvier J. Specific labeling and assignment strategies of valine methyl groups for NMR studies of high molecular weight proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2013;57:251–262. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9785-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tugarinov V, Kay LE. An isotope labeling strategy for methyl TROSY spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:165–172. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000013824.93994.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lichtenecker R, Ludwiczek ML, Schmid W, Konrat R. Simplification of protein NOESY spectra using bioorganic precursor synthesis and NMR spectral editing. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5348–5349. doi: 10.1021/ja049679n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lichtenecker RJ. Synthesis of aromatic (13)C/(2)H-alpha-ketoacid precursors to be used in selective phenylalanine and tyrosine protein labelling. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:7551–7560. doi: 10.1039/c4ob01129e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lichtenecker RJ, Weinhaupl K, Schmid W, Konrat R. alpha-Ketoacids as precursors for phenylalanine and tyrosine labelling in cell-based protein overexpression. J Biomol NMR. 2013;57:327–331. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9796-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schorghuber J, Sara T, Bisaccia M, Schmid W, Konrat R, Lichtenecker RJ. Novel approaches in selective tryptophan isotope labeling by using Escherichia coli overexpression media. Chembiochem. 2015;16:746–751. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]