Abstract

Background

The purpose of this investigation was to compare a new psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa, Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy (ICAT), with an established treatment, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced (CBT-E).

Method

Eighty adults with symptoms of bulimia nervosa were randomized to ICAT or CBT-E for 21 sessions over 19 weeks. Bulimic symptoms, measured by the Eating Disorder Examination, were assessed at baseline, end of treatment, and 4-month follow-up. Treatment outcome, as measured by binge eating frequency, purging frequency, global eating disorder severity, emotion regulation, self-oriented cognition, depression, anxiety, and self-esteem, was determined using generalized estimating equations, logistic regression, and a general linear model (intent-to-treat).

Results

Both treatments were associated with significant improvement in bulimic symptoms as well as all measures of outcome, and no statistically significant differences were observed between the two conditions at end of treatment or follow-up. Intent-to-treat abstinence rates for ICAT (37.5% at end of treatment, 32.5% at follow-up) and CBT-E (22.5% at both end of treatment and follow-up) were not significantly different.

Conclusions

ICAT was associated with significant improvements in bulimic and associated symptoms that did not differ from those obtained with CBT-E. This initial randomized controlled trial of a new individual psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa suggests that targeting emotion and self-oriented cognition in the context of nutritional rehabilitation may be efficacious and worthy of further study.

Bulimia nervosa, an eating disorder characterized by binge eating episodes, compensatory behaviors including self-induced vomiting, and overvaluation of body shape and weight, is associated with high rates of medical complications (Mehler, 2011) psychiatric comorbidity (Wonderlich et al. 1997; Fichter et al. 2008), and psychosocial impairment (Crow & Peterson, 2003) as well as significant mortality rates (Crow et al. 2009). Although psychological and pharmacological treatments have been found to reduce bulimic symptoms (Mitchell et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2007), the fact that treatment outcome studies have been characterized by partial response, significant attrition, and considerable relapse indicates that additional interventions are needed (Mitchell et al., 1996). In addition, the lack of implementation of evidence-based eating disorder treatments by clinicians in the community (Wallace & von Ranson, 2011; Mussell et al., 2000) and the notable drop-out rates across bulimia nervosa treatment outcome studies (Shapiro et al., 2007) suggest that a wider range of effective interventions are necessary to improve long-term efficacy, increase levels of treatment acceptability among clinicians as well as patients, and provide a broader range of evidence-based treatment options for dissemination.

One potential strategy to enhance treatment efficacy is to target mechanisms that are thought to cause and maintain psychopathology symptoms (Rieger et al., 2010). A number of studies, particularly recent investigations using ecological momentary assessment, demonstrate that negative emotional states often precipitate bulimic symptoms (Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2011; Smyth et al., 2007) and that negative emotions may temporarily subside after bulimic behaviors occur (Smyth et al., 2007). These data suggest that binge eating and purging may serve as a self-regulation strategy for negative emotions and that addressing maladaptive coping in response to these emotions, and behavioral and cognitive patterns that elicit negative emotions, may reduce bulimic symptoms. Additional research indicates that a type of self-oriented cognition described as self-discrepancy, involving the magnitude of the difference between a person’s self-perception and their self-evaluative standards, may be an important aspect of eating disorder symptoms (Higgins et al., 1986; Strauman et al., 1991). Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy (ICAT), a new psychotherapeutic treatment for bulimia nervosa, emphasizes emotion regulation, adaptive coping, self-directed behaviors including nutritional consumption, interpersonal relationships, and self-oriented cognitive patterns including self-discrepancy (Wonderlich et al., 2010). This treatment is based on a multidimensional model of bulimic symptoms that emphasizes momentary relationships between maintaining variables and bulimic behaviors (Wonderlich et al., 2008) and specifically focuses on these maintenance mechanisms during four phases of treatment (Wonderlich et al., 2010). The first phase of treatment emphasizes strategies that address treatment ambivalence (Miller & Rollnick, 1991) as well as the importance of emotions in maintaining bulimic symptoms. The second phase of treatment focuses on adaptive coping strategies, particularly for urge management, and targets nutritional deprivation through structured meal planning. The third phase of treatment is individualized to address one or more of three potential problems areas hypothesized to maintain bulimic symptoms by eliciting negative affect: 1) self-directed behavior styles including excessive self-control and self-neglect (Benjamin, 1974, 1993); 2) interpersonal problems, including submissiveness, withdrawal, and blaming (Benjamin, 1974, 1993); and 3) self-discrepancy and evaluative standards (Higgins et al., 1986; Strauman et al., 1991). The final phase of treatment emphasizes healthy lifestyle plans and relapse prevention. ICAT includes a psychoeducational patient workbook and eight “core skills” that are emphasized in treatment and provided to the patient in the form of laminated skill cards and portable technology.

The aim of the current investigation was to compare the efficacy of ICAT for the treatment of bulimic symptoms to a cognitive-behavioral intervention, Cognitive-Behavior Therapy-Enhanced (CBT-E; Fairburn, 2008). Cognitive-behavioral treatment was selected as the most conservative and suitable comparison condition because this approach has been described as the treatment of choice for bulimia nervosa (Wilson, 2005) and has been given the highest rating in the National Institute for Clinical Excellence review of evidence based treatments (NICE, 2004). Outcome measurement was based on bulimic symptoms, overall eating disorder severity, and co-occurring psychiatric symptoms (i.e., depression, anxiety) as well as measures of hypothesized maintenance mechanisms of bulimia nervosa including emotion regulation and cognitive self-discrepancy

METHOD

Participants

The sample included 80 adults (n = 72 females, 90%; see Table 1) from two USA clinical sites (Minnesota and North Dakota). Potential participants were recruited from the community using advertisements as well as referrals from local eating disorder treatment clinics and other health professionals. Criteria were broadened to include participants with both DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and proposed DSM-5 criteria for bulimia nervosa as well as individuals who reported compensatory behaviors, like self-induced vomiting, accompanied by subjective bulimic episodes (Fairburn, 2008) at least weekly for three months prior to enrollment. Broader inclusion criteria were utilized based on previous findings that individuals with subthreshold bulimic symptoms resemble those who meet full diagnostic criteria on eating disorder, psychiatric, and impairment measures (Crow et al., 2012) and to increase the heterogeneity of the sample and potential generalizability. Diagnostic status was determined by trained interviewers using the Eating Disorder Examination (Fairburn, 2008). Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or lactation, body mass index less than 18, lifetime diagnosis of bipolar or psychotic disorder, current diagnosis of substance use disorder, medical or psychiatric instability including acute suicide risk, or current psychotherapy. Participants on a stable dose of antidepressant medication for a minimum of six weeks were allowed to participate.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics by Treatment Group

| Characteristic | ICAT (n = 40) | CBT-E (n = 40) | Total (N = 80) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 25.8 (8.2) | 28.8 (10.8) | 27.3 (9.6) | t78 = 1.39, p = .168 |

| Female (n, %) | 36 (90.0%) | 36 (90.0%) | 72 (90.0%) | Fisher’s Exact p = 1.00 |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | χ25 = 4.80, p = .441 | |||

| White | 35 (87.5%) | 35 (87.5%) | 70 (87.5%) | |

| Asian | 1 (2.5%) | 4 (10.0%) | 5 (6.3%) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (2.5%) | |

| African American | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| Native American | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| Other | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| Never married (n, %) | 27 (67.5%) | 28 (70.0%) | 55 (68.8%) | Fisher’s Exact p = 1.00 |

| College degree (n, %) | 15 (37.5%) | 21 (52.5%) | 36 (45.0%) | Fisher’s Exact p = .261 |

| Sub-threshold BN (n, %) | 11 (27.5%) | 11 (27.5%) | 22 (27.5%) | Fisher’s Exact p = 1.00 |

| Current SCID Diagnoses (n, %) | ||||

| Mood disorder | 9 (22.5%) | 6 (15.0%) | 15 (18.8%) | Fisher’s Exact p = .568 |

| Anxiety disorder | 12 (30.0%) | 7 (17.5%) | 19 (23.8%) | Fisher’s Exact p = .293 |

| Lifetime SCID Diagnoses (n, %) | ||||

| Mood disorder | 27 (67.5%) | 26 (65.0%) | 53 (66.3%) | Fisher’s Exact p = 1.00 |

| Anxiety disorder | 23 (57.5%) | 14 (35.0%) | 37 (46.3%) | Fisher’s Exact p = .072 |

| Substance abuse/dependence | 22 (55.0%) | 18 (45.0%) | 40 (50.0%) | Fisher’s Exact p = .503 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean, SD) | 23.5 (5.5) | 24.4 (5.6) | 23.9 (5.5) | t78 = 0.75, p = .457 |

Abbreviations: ICAT = Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy; CBT-E = Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced; SD = standard deviation; BN = bulimia nervosa; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; BMI = body mass index

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at each of the recruitment sites, as well as by the University of Wisconsin where the Treatment Adherence and Acceptability Assessment Center was based. Written informed consent was obtained during the orientation meeting after the study had been described in detail to potential participants prior to data collection.

Measures

Treatment outcome assessment for bulimic symptoms included frequency of binge eating episodes and compensatory behaviors as measured by the Eating Disorder Examination (Fairburn, 2008), which was also used as a measure of associated eating disorder symptoms, including shape and weight concerns, abstinence from bulimic symptoms, and global eating disorder severity. Previous studies have supported the reliability and the validity of the Eating Disorder Examination (Fairburn, 2009; Berg et al., 2012). Experienced, trained, master’s and doctoral-level assessors who conducted the interviews were blind to participant randomization. Assessors were trained initially using didactics and role playing and communicated throughout the study by teleconference and e-mail in order to prevent drift. Inter-rater reliability ratings based on audiotape ratings were conducted on a 20% random sample (n = 16) of the baseline Eating Disorder Examination interviews. Overall inter-rater reliability (based on intraclass correlation coefficients) for the Eating Disorder Examination subscales and global score ranged from 0.909 (Weight Concerns) to 0.999 (Restraint). Frequency of bulimic behaviors (e.g., binge eating, purging) was also assessed through weekly written recalls of these symptoms which were provided by the participant at their regular treatment sessions throughout the trial. Additional outcome measures included the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1961) to assess depressive symptoms, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire (Rosenberg, 1979) to examine self-esteem, and the Spielberger State/Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1970) to measure anxiety. Several measures were also included to assess specific variables targeted by ICAT including the Selves Interview (Higgins et al., 1986) to examine self-discrepancy, and the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) to assess emotion regulation. Participants completed these measures at baseline, end of treatment, and 4-month follow-up. In addition, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First et al., 2002) was administered at baseline to assess co-occurring psychopathology diagnoses.

Randomization

Participants were randomized to treatment condition by the independent bio-statistician (RDC). Randomization was performed in blocks of four participants stratified by site, diagnosis (full vs. partial BN) and therapist.

Treatment

Both treatments consisted of twenty-one 50-minute individual psychotherapy sessions over 19 weeks, with twice weekly sessions for the first four weeks. As described above, ICAT (Wonderlich et al., 2010) includes four phases. The first phase emphasizes motivational enhancement techniques to encourage treatment engagement and reduce ambivalence (Miller & Rollnick, 1991). In addition, the identification of emotional states, as well as self-monitoring of eating patterns, behaviors, and emotions are introduced. The second phase focuses on nutritional rehabilitation through meal planning as well as adaptive coping strategies, particularly for managing urges to engage in bulimic behaviors. The third phase emphasizes modifying behaviors in response to stimulus situations and emotions, which are identified as antecedents of bulimic behavior. Interpersonal patterns, self-directed styles (e.g., self-protection, extreme self-control), and self-discrepancy are discussed in the context of situations that elicit bulimic symptoms. The final phase of treatment emphasizes relapse prevention and healthy lifestyle strategies. CBT-E (Fairburn, 2008, Fairburn et al., 2009) is a recently revised version of cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating (Fairburn et al., 1993) that has been adapted for transdiagnostic treatment of eating disorder symptoms. CBT-E was selected because initial data suggest that it may be associated with higher abstinence and remission rates compared to earlier versions of the treatment (Fairburn et al., 2009), making it a potentially more rigorous comparison condition. The focused version of CBT-E (Fairburn, 2008) was utilized and includes four stages: an introductory stage that emphasizes psychoeducation, normalization of eating patterns, and symptom self-monitoring; a second, brief stage to review progress and formulate plans for the subsequent treatment phase; a middle stage that emphasizes the elimination of dieting, reduces shape checking and avoidance behaviors, educates about mood tolerance, and targets the overevaluation of shape and weight; and a final stage that focuses on maintaining progress and minimizing relapse risk.

Four Ph.D. psychologists (two at each site) who served as study therapists were initially trained in didactic sessions and conducted supervised training cases before administering the treatments for this study. All four clinicians administered both types of therapy, had been trained in cognitive-behavioral techniques for previous randomized controlled trials for bulimia nervosa (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2011), and were re-trained for both treatments used in this investigation. Study therapists met for weekly teleconference supervision with the study supervisors (SAW and CBP) throughout the trial.

Therapist adherence was evaluated for both treatment arms. A random sampling of audiotapes were reviewed by independent graduate student raters at the University of Wisconsin and supervised by one of the study investigators (TLS). A modified version of a previous CBT measure (Loeb et al., 2011) was used to evaluate CBT-E adherence. ICAT therapist adherence was evaluated with a measure designed for this study. Raters were 3 advanced doctoral students in psychology and one psychology undergraduate with research experience. Teams of two raters evaluated each treatment. Interrater reliability was established before raters began coding for study purposes. Interrater reliability for each team was acceptable (CBT-E = .90; ICAT = .81). Raters evaluated approximately 20% of randomly selected patient/therapist dyads, reviewing 15-minute segments from three randomly selected audio-taped sessions for each selected dyad to capture data from early, middle, and later phases of treatment. If a recording from a selected session was missing or inaudible, an adjacent session was rated. When ratings for a taped segment failed to meet an intraclass correlation coefficient of at least .80, raters created consensus ratings. Intraclass correlations were calculated in a two-way mixed model with absolute agreement. Overall, therapists demonstrated good adherence. CBT-E therapists’ mean rating across all items was 6.2 (on a 7 point Likert-type scale) and ICAT therapists’ mean rating was 3.0 (on a 4 -point Likert-type scale) where higher numbers indicate greater adherence.

Statistical Analyses

Sample size calculations for this study were based upon the procedures described by Hedeker, Gibbons and Waternaux (Hedeker et al., 1999) for determining power in two-group longitudinal studies with attrition. Power estimates assumed a 20% attrition rate and a two-tailed alpha of .05. The enrolled sample size of 40 subjects per group (80 total) provided a power of .80 to detect an attrition-adjusted standardized effect size of .49.

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.0.0. Significance tests were based on a two-tailed alpha of .05. Treatment groups were compared on baseline characteristics using independent samples t-tests for continuous measures, chi-square for categorical measures, and Fisher’s Exact tests for dichotomous measures. Treatments groups were compared on outcome measures at baseline using a generalized estimating equations (GEE; Zeger & Liang, 1986) model with a negative binomial log link response function for behavioral count measures (objective and subjective bulimic episodes as well as purging frequency), logistic regression for abstinence and global Eating Disorder Examination categorization, and a general linear model for continuous measures. All models controlled for site and DSM-IV eating disorder diagnosis (i.e., bulimia nervosa vs. subthreshold bulimia nervosa). Abstinence was defined as no objective binge eating, vomiting or laxative use in the past four weeks based upon the Eating Disorder Examination interview. Additional analyses were conducted on the global Eating Disorder Examination scores which were categorized as to whether participants were within one standard deviation of the community mean (i.e., below 1.74; Fairburn et al., 2009).

Missing data for continuous outcome measures at end-of-treatment and follow-up were imputed using multiple imputation (MI) based upon fully conditional Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC; Schafer, 1987) modeling. The final analysis model was based upon the averaged values of 100 separate imputations (Rubin, 1987). Those participants with missing binge eating and purging (i.e., vomiting or laxative use) data at end-of-treatment or follow-up were considered not abstinent. Treatment groups were then compared separately at end-of-treatment and follow-up on measures of outcome and mechanism using GEE, logistic regression or a general linear model comparable to those described above. Covariates included site, DSM-IV eating disorder diagnosis (i.e., bulimia nervosa versus subclinical variant), and baseline measurement (with the exception of abstinence). Analyses based upon these same models were conducted separately for each treatment condition to evaluate change in outcome measures from baseline to end-of-treatment or 4-month follow-up. A GEE model with a negative binomial response function was used to compare treatment groups on weekly binge eating and purging frequency using all available data (i.e., no imputation of missing values). The model included effects for treatment group, session number (linear and quadratic components), baseline measurement, site, and DSM-IV eating disorder diagnosis.

RESULTS

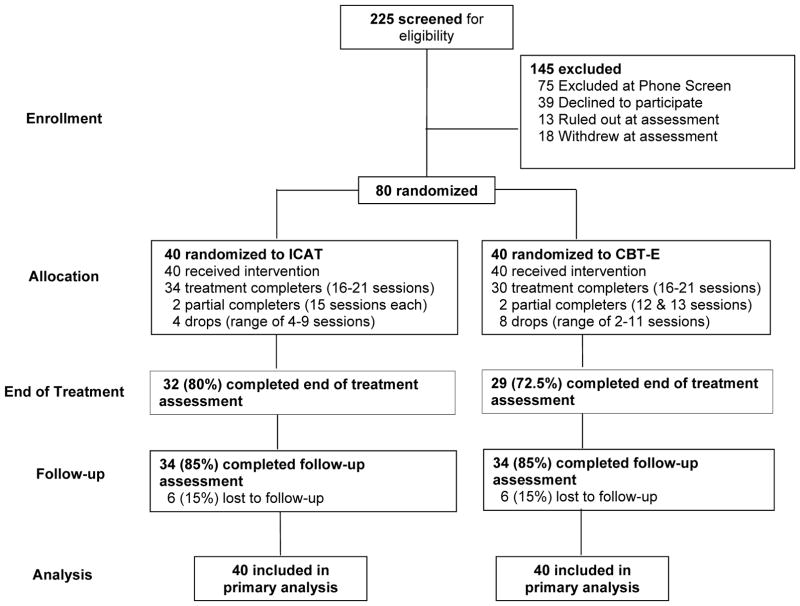

Patient Flow

Figure 1 presents patient flow through the study. A total of 80 participants were randomized, 40 each to ICAT and CBT-E. A total of 64 participants (80%) completed treatment, defined as attending at least 16 sessions; 4 participants (5%) were classified as partial completers, defined as attending at least 12–15 sessions; and 12 participants (15%) were considered treatment non-completers, defined as attending 11 sessions or fewer. End of treatment assessments were completed for 61 participants (76.3%) and follow-up assessments were obtained for 68 participants (85%; treatment non-completers were invited to return for follow-up assessments).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of study participants

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics at baseline are presented in Table 1. Participants were predominantly female (90%), white (87.5%), and the majority (72.5%) met full threshold DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa. There were no significant differences between treatments or sites on any baseline characteristic.

Treatment Retention

A total of 34 ICAT participants (85%) and 30 CBT-E participants (75%) completed treatment. Treatment conditions did not differ significantly in terms of completion rates, average number of sessions completed, or the completion of end of treatment or follow-up assessments (Table 2).

Table 2.

Completion Status by Treatment Group

| Characteristic | ICAT (n = 40) | CBT-E (n = 40) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Completion (n, %) | χ22 = 1.58, p = .453 | ||

| Completer | 34 (85.0%) | 30 (75.0%) | |

| Partial Completer | 2 (5.0%) | 2 (5.0%) | |

| Drop out | 4 (10.0%) | 8 (20.0%) | |

| Sessions completed (mean, SD) | 18.6 (4.3) | 17.2 (5.4) | t78 = −1.27, p = .209 |

| EOT Assessment (n, %) | 32 (80.0%) | 29 (72.5%) | Fisher’s Exact p = .600 |

| Follow-up Assessment (n, %) | 34 (85.0%) | 34 (85.0%) | Fisher’s Exact p = 1.00 |

Abbreviations: ICAT = Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy; CBT-E = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced; SD = standard deviation; EOT = end-of-treatment

Primary Treatment Outcome

Table 3 presents descriptive information on primary measures of outcome, binge eating and purging frequency from the EDE, at baseline, end of treatment and 4-month follow-up by treatment group. Treatment groups did not differ significantly at baseline on primary measures of outcome. No significant differences were found between treatment groups at end of treatment or 4-month follow-up on binge eating or purging frequency (all p’s > .17). In addition, no significant differences were found between treatment groups in the trajectory of binge eating or purging episodes reported via weekly symptom recall (all p’s > .24).

Table 3.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes by Treatment Group

| Primary Outcomes | Pretreatment | End of Treatment | 4-Month Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| ICAT (n = 40) | CBT-E (n = 40) | ICAT (n = 40) | CBT-E (n = 40) | ICAT (n = 40) | CBT-E (n = 40) | |

| OBE episodes (mean, SD) | 23.2 (19.6) | 22.4 (21.0) | 6.1 (14.8) | 5.3 (9.1) | 5.6 (9.2) | 8.5 (13.7) |

|

|

||||||

| % reduction in OBE (%) | 73.7% | 76.3% | 75.9% | 62.1% | ||

|

|

||||||

| Purging episodes (mean, SD) | 30.6 (27.0) | 30.5 (32.6) | 8.3 (20.8) | 7.4 (11.5) | 8.6 (15.9) | 10.1 (16.3) |

|

|

||||||

| % reduction in purging (%) | 72.9% | 75.7% | 71.9% | 66.9% | ||

|

|

||||||

| EDE Global (mean, SD) | 3.3 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.1) | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.0) |

| Binge-Purge Abstinence (n, %) | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (37.5%) | 9 (22.5%) | 13 (32.5%) | 9 (22.5%) |

| Global EDE within 1 SD of community mean (n, %) | 3 (7.5%) | 6 (15.0%) | 19 (47.5%) | 15 (37.5%) | 22 (55.0%) | 20 (50.0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Hypothesized Mechanisms | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Ideal Self-discrepancy (mean, SD) | −0.5 (2.7) | −0.3 (2.4) | −1.7 (2.2) | −1.6 (2.4) | −1.8 (2.2) | −2.1 (1.7) |

| Ought Self-discrepancy (mean, SD) | −0.5 (2.2) | −0.8 (1.7) | −2.1 (1.7) | −1.7 (1.5) | −2.3 (2.0) | −1.7 (1.5) |

| DERS Total (mean, SD) | 100.6 (18.4) | 98.4 (17.6) | 88.9 (13.2) | 90.5 (13.7) | 90.0 (13.8) | 93.0 (13.3) |

|

| ||||||

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| SBE episodes (mean, SD) | 14.0 (18.7) | 11.5 (13.6) | 3.3 (4.4) | 5.1 (7.8) | 3.0 (6.5) | 4.6 (7.1) |

| EDE Restraint (mean, SD) | 3.0 (1.7) | 2.7 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.2) |

| EDE Eating Concerns (mean, SD) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.4) | 0.9 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.9 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.1) |

| EDE Shape Concerns (mean, SD) | 3.9 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.2) |

| EDE Weight Concerns (mean, SD) | 3.8 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.3) |

| BDI Total (mean, SD) | 19.5 (11.5) | 17.9 (11.7) | 8.6 (8.0) | 9.3 (9.8) | 10.4 (11.5) | 8.9 (9.3) |

| RSE Total (mean, SD) | 2.8 (1.8) | 3.3 (1.6) | 4.4 (1.8) | 4.3 (1.5) | 3.9 (2.0) | 4.4 (1.4) |

| SSAI Total (mean, SD) | 46.9 (13.3) | 45.1 (12.5) | 35.3 (12.5) | 35.2 (10.1) | 35.9 (13.7) | 37.5 (10.8) |

| STAI Total (mean, SD) | 52.4 (13.6) | 50.9 (11.3) | 38.2 (13.2) | 39.5 (10.0) | 39.5 (14.2) | 41.5 (11.4) |

Abbreviations: ICAT = Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy; CBT-E = Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced; OBE = objective binge eating; EDE = Eating Disorder Examination; Ideal and Ought Self-discrepancy = Ideal Self-Discrepancy and Ought Self-Discrepancy from the Selves Interview; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; SBE = subjective binge eating; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; RSE = Rosenberg Self-Esteem; SSAI = Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory; STAI = Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale.

Secondary Outcome Analysis

No significant differences were found on any secondary measures of outcome (i.e., eating disorder severity, co-occurring psychiatric symptoms, maintenance mechanisms) between treatment groups at end of treatment or 4-month follow-up (Table 3). Table 4 presents estimates of differences and 95% confidence intervals between treatments at end of treatment and 4-month follow-up on primary and secondary measures of outcome.

Table 4.

Differences on Primary and Secondary Outcomes and 95% Confidence Intervals Between Treatments

| Primary Outcomes | End of Treatment1 | 4-Month Follow-up1 |

|---|---|---|

| OBE episodes | 0.30 (−2.15, 2.75) | −1.88 (−4.53, 0.78) |

| Purging episodes | −0.30 (−3.74, 3.15) | 0.30 (−3.86, 4.44) |

| EDE Global | −0.15 (−0.53, 0.24) | −0.25 (−0.69, 0.19) |

|

| ||

| Hypothesized Mechanisms | ||

|

| ||

| Ideal Self-discrepancy | −0.08 (−1.08, 0.93) | 0.30 (−0.57, 1.18) |

| Ought Self-discrepancy | −0.47 (−1.41, 0.47) | −0.55 (−1.34, 0.23) |

| DERS Total | −2.44 (−7.68, 2.79) | −3.83 (−9.04, 1.37) |

|

| ||

| Secondary Outcomes | ||

|

| ||

| SBE episodes | −1.22 (−3.18, 0.75) | −1.00 (−2.73, 0.73) |

| EDE Restraint | 0.07 (−0.41, 0.56) | −0.15 (−0.64, 0.35) |

| EDE Eating Concerns | −0.11 (−0.42, 0.20) | −0.27 (−0.71, 0.18) |

| EDE Shape Concerns | −0.29 (−0.77, 0.20) | −0.37 (−0.89, 0.16) |

| EDE Weight Concerns | −0.16 (−0.69, 0.37) | −0.17 (−0.74, 0.40) |

| BDI Total | −1.17 (−4.75, 2.41) | 0.91 (−3.19, 5.01) |

| RSE Total | 0.31 (−0.37, 1.00) | −0.20 (−0.88, 0.49) |

| SSAI Total | −0.40 (−5.22, 4.44) | −2.37 (−7.23, 2.50) |

| STAI Total | −2.12 (−6.73, 2.50) | −2.77 (−7.68, 2.14) |

Covariate-adjusted estimate (95% confidence intervals) of difference between ICAT and CBT-E: Positive values indicate estimate for ICAT is higher than the estimate for CBT-E; negative values indicate estimate for CBT-E is higher than the estimate for ICAT.

Abbreviations: ICAT = Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy; CBT-E = Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced; OBE = objective binge eating; EDE = Eating Disorder Examination; Ideal and Ought Self-discrepancy = Ideal Self-Discrepancy and Ought Self-Discrepancy from the Selves Interview; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; SBE = subjective binge eating; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; RSE = Rosenberg Self-Esteem; SSAI = Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory; STAI = Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale

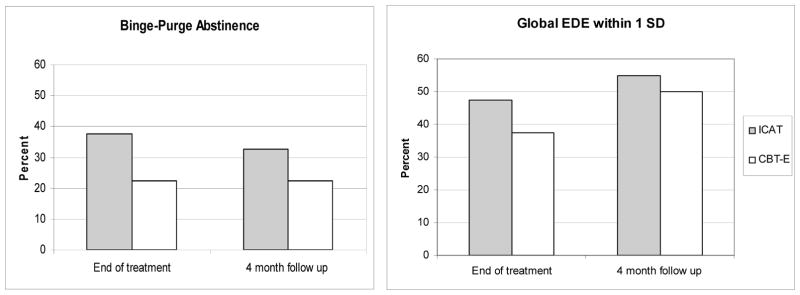

Bulimic abstinence rates for ICAT were 37.5% at end of treatment and 32.5% at follow-up, compared to 22.5% at both end of treatment and follow-up for CBT-E. The percentage of ICAT participants within one standard deviation of the community mean on the EDE global score was 47.5% at end of treatment and 55.0% at follow-up, compared to 37.5% at end of treatment and 50% at follow-up for CBT-E.

Both treatment groups showed significant within-group improvement at end of treatment and follow-up on all outcome measures (p < .05). Within-group effect sizes on eating disorder outcomes (i.e., objective bulimic episodes, purging episodes, EDE global scores) at end-of-treatment ranged from 0.83–1.50 for ICAT and 0.71–1.30 for CBT-E and at follow-up ranged from 0.82–1.61 for ICAT and 0.63–1.32 for CBT-E.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study indicate that both ICAT and CBT-E were associated with considerable improvements in bulimia nervosa symptoms, cognitive self-discrepancy, emotional regulation, and comorbid psychiatric symptoms, and that these treatment conditions did not significantly differ in their effects on these outcome variables. Baseline to end of treatment effect sizes for both treatments on measures of eating disorder symptoms were moderate to large. This study is innovative in that it compares a new psychotherapeutic treatment for bulimic symptoms to a version of the treatment that is currently considered the most empirically supported treatment for bulimia nervosa (Wilson, 2005; NICE, 2004) in a randomized controlled trial.

The findings for the present study may be considered reliable for the following reasons. First, the study had sufficient statistical power to adequately test the outcome measures including the reduction of core bulimic symptoms and eating disorder psychopathology. Second, both treatments were manualized and adherence was substantial, providing reasonable standardization of the interventions. Third, both treatments were regularly and rigorously supervised to promote adherence to the conceptual models and treatment techniques outlined for each treatment. Fourth, all four Ph.D. psychologists delivering the treatment had high levels of expertise in administering evidence-based treatments for eating disorders and had provided these types of psychotherapies in previous randomized, controlled trials for bulimia nervosa. Finally, the study was conducted at two sites in a multisite design, enhancing the potential generalizability of those findings.

The results suggest that there were no differences between the treatments on any outcome measure. In addition, the low levels of attrition indicate that the clinicians effectively delivered both treatments and that the participants found the treatment at least reasonably acceptable. Regarding bulimic symptomatology, there were no treatment-related differences in abstinence rates, frequency of binge eating and compensatory symptoms, or percent of participants within one standard deviation of the community mean on the global measure of eating disorder severity. Furthermore, the percent of participants meeting a global severity criterion at follow-up (i.e., within one standard deviation of the community mean on the Eating Disorder Examination Global score) was roughly comparable to a recent study using CBT-E to treat a transdiagnostic sample of participants with eating disorders (Fairburn et al., 2009). Both treatments were also associated with significant improvements in measures of psychiatric symptoms (i.e., depression, anxiety) as well as hypothesized mechanisms of action for ICAT (i.e., cognitive self-discrepancy, emotion regulation). It is notable that the treatments did not differ in these particular outcomes in spite of targeting different putative mechanisms of bulimia nervosa. Thus, there was no evidence that either treatment was superior to the other on any variable.

The findings should not be interpreted without considering limitations of the study. First, there was no wait-list control group or nonspecific treatment condition in the design, thus making it impossible to rule out the possibility that the changes identified were due to the simple occurrence of treatment or to nonspecific therapeutic factors. Although there is accumulating evidence to suggest that bulimia nervosa does not improve in wait-list conditions (Shapiro, 2007), we cannot rule out the possibility that our effects are nonspecific responses to treatment. Second, the sample size did not provide adequate statistical power to test dichotomous outcome measures (e.g., abstinence rates) and it is possible that with a larger sample size, some of the statistical effects in the study may have reached a level of significance that would alter the conclusions. Third, we did not conduct an a priori non-inferiority statistical design and therefore cannot make statements about the relative comparability or equivalence of the results. Fourth, because the enhanced version of CBT was utilized as a comparison condition, these results would not necessarily generalize to CBT using an older version of the manual (Fairburn et al., 1993). Finally, because ICAT was intentionally designed to include some aspects of cognitive-behavioral therapy (e.g., self-monitoring), the two treatments had some degree of overlap. However, the psychotherapies are distinct in a number of respects including ICAT’s emphasis on motivational enhancement, emotion, self-discrepancy, and interpersonal patterns as well as the underlying psychopathology model.

CONCLUSION

ICAT is a new treatment for symptoms of bulimia nervosa that is based on the premise that momentary functional relationships between emotional states and bulimic behaviors can be effectively targeted in treatment along with other hypothesized mechanisms of bulimia nervosa. Specifically, the model underlying ICAT based on ecological momentary assessment data posits that negative affect increases in the moments preceding bulimic behaviors and that, in turn, bulimic behaviors temporarily reduce negative affect (Smyth et al., 2007). Although retaining some features of traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy (e.g., self-monitoring, promotion of regular eating behavior; Fairburn, 2008, 1993), ICAT uniquely targets factors hypothesized to precipitate negative emotion and risk for bulimic behaviors, including relationship problems, excessive personal self-standards associated with self-discrepancy, and harsh or rigid self-directed behaviors. The present findings suggest that ICAT is a promising new treatment for bulimia nervosa that warrants further study with larger samples in an effort to replicate the present findings and more rigorously examine the underlying conceptual model and possible mechanisms of action of this psychotherapy.

Figure 2.

Binge Eating and Purging Abstinence and Percent of Participants within 1 SD of Community Mean on Global EDE by Treatment Group (N = 80; ICAT n = 40; CBT-E n = 40)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Tricia Cook Myers, Kathryn Miller, and Lorraine Swan- Kremeier for serving as therapists on the study, Drs. Zafra Cooper and Christopher Fairburn for their consultation regarding psychotherapy administration, Li Cao, M.S. and Ann Erickson for their contributions to data analysis, and Kelly Berg, Ph.D., Nora Durkin, M.A., Scott Engel, Ph.D., Leah Jappe, B.A., Jason Lavender, Ph.D., and Heather Simonich, M.A., for their assistance with data collection, assessment interviewing, and manuscript preparation.

Supported by grants R01DK61912, R01DK 61973, and P30 DK 60456 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, grants R34MH077571, R01MH059674, T32MH082761, K02 MH65919 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Neuropsychiatric Research Institute.

Drs. Crosby and Wonderlich report no competing interests. Drs. Mitchell and Peterson receive royalties from Guilford Press. Dr. Crow reports research support from Alkermes and Shire. Dr. Mitchell reports research support from Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKlein. Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT00773617

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin LS. Interpersonal Treatment of Personality Disorders. Guilford; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin LS. Structural analysis of social behavior. Psychological Review. 1974;81:392–425. [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Peterson CB, Frazier P, Crow SC. Psychometric evaluation of the Eating Disorder Examination and Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45:428–438. doi: 10.1002/eat.20931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow SJ, Agras WS, Halmi K, Mitchell JE, Kraemer HC. Full syndromal versus subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder: A multicenter study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;302:309–318. doi: 10.1002/eat.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow SJ, Peterson CB, Swanson SA, Raymond NC, Specker S, Eckert ED, Mitchell JE. Increased mortality in bulimia nervosa and other eating disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1342–1346. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow SJ, Peterson CB. The economic and social burden of eating disorders. In: Maj M, Halmi KA, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Sartorius N, editors. WPA Series Evidence and Experience in Psychiatry (Volume 6): Eating Disorders. John Wiley; New York: 2003. pp. 383–397. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll H, O’Connor ME, Bohn K, Hawker DM, Wales JA, Palmer RL. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:311–319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. Guilford; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, Wilson GT. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Binge Eating and Bulimia Nervosa: A Comprehensive Treatment Manual. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. Guilford; New York: 1993. pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Hedlund S. Long term course of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa: relevance for nosology and diagnostic criteria. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:577–586. doi: 10.1002/eat.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Patient-Version (SCID-I/P) New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavior Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Haedt-Matt A, Keel PK. Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: a meta analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:660–681. doi: 10.1037/a0023660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD, Waternaux C. Sample size estimation for longitudinal designs with attrition: comparing time-related contrasts between two groups. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1999;24:70–93. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET, Bond RN, Klein R, Strauman TJ. Self-discrepancies and emotional vulnerability: How magnitude, accessibility and type of discrepancy influence affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:5–15. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb KL, Wilson GT, Labouvie E, Pratt EM, Hayaki J, Walsh BT, Agras WS, Fairburn CG. Therapeutic alliance and treatment adherence in two interventions for bulimia nervosa: A study of process and outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1097–1107. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehler P. Medical complications of bulimia nervosa and their treatments. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44:95–104. doi: 10.1002/eat.20825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. Guilford; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Agras WS, Crow S, Halmi K, Fairburn CG, Bryson S, Kraemer H. Stepped care and cognitive-behavioural therapy for bulimia nervosa: Randomised trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;185:391–397. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.082172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, de Zwaan M, Roerig JL. Drug therapy for patients with eating disorders. Current Drug Targets CNS Neurological Disorders. 2003;2:17–29. doi: 10.2174/1568007033338850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Hoberman HN, Peterson CB, Mussell M, Pyle RL. Research on the psychotherapy of bulimia nervosa: Half empty or half full. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1996;20:219–229. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199611)20:3<219::AID-EAT1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussell MP, Crosby RD, Crow SJ, Knopke AJ, Peterson CB, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE. Utilization of empirically supported psychotherapy treatments for individuals with eating disorders: A survey of psychologists. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;27:230–237. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200003)27:2<230::aid-eat11>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) NICE Clinical Guideline No. 9. London: NICE; 2004. Eating Disorders – Core Interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, related eating disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Rieger E, Van Buren DJ, Bishop M, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Welch R, Wilfley DE. An eating disorder-specific model of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-ED): Casual pathways and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the Self. Basic; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. Chapman & Hall; London: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JR, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Sedway JA, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Bulimia nervosa treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:321–336. doi: 10.1002/eat.20372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Strauman TJ, Vookles J, Barenstein V, Chaiken S, Higgins ET. Self-discrepancies and vulnerability to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:946–956. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace LM, von Ranson KM. Treatment manuals: Use in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2011;49:815–820. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatments of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;1:439–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Smith TL, Klein M, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Engel SG. Integrative cognitive-affective therapy for bulimia nervosa. In: Grilo GG, Mitchell JE, editors. The Treatment of Eating Disorders: A Clinical Handbook. Guilford; New York: 2010. pp. 317–338. [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Peterson CB, Robinson MD, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Smith T, Klein M, Lysne C, Crow S, Strauman T, Simonich H. Examining the conceptual model of integrative cognitive-affective therapy for BN: Two assessment studies. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:748–754. doi: 10.1002/eat.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE. Eating disorders and comorbidity: Empirical, conceptual and clinical implications. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1997;33:381–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY. The analysis of discrete and continuous longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]