Abstract

Sulfurization of anionic N-heterocyclic dicarbene, [:C{[N(2,6-Pri2C6H3)]2CHCLi}]n (2), with elemental sulfur (in a 1:2 ratio) in Et2O at low temperature gives 3 by inserting two sulfur atoms into the Li–C (i.e., C2 and C4) bonds in polymeric 2. Further reaction of 3 with 2 equiv of elemental sulfur in THF affords 4• via unexpected C–H bond activation, which represents the first anionic dithiolene radical to be structurally characterized in the solid state. Alternatively, 4• may also be synthesized directly by reaction of 1 with sulfur (in a 1:4 ratio) in THF. Reaction of 4• with GeCl2·dioxane gives an anionic germanium(IV)–bis(dithiolene) complex (5). The nature of the bonding in 4• and 5 was probed by experimental and theoretical methods.

Metal–dithiolene complexes, extensively studied since the early 1960s,1–10 are intriguing not only due to their unique structural and bonding motifs but also for their remarkable capabilities in such disparate fields as materials science4,10 and biological systems.2,11 While both molybdenum and tungsten enzymes contain the dithiolene unit,2,5 transition metal–bis-dithiolenes, possessing unique optical, conductive, and magnetic properties, have shown promise in the development of optoelectronic devices.4,7,10

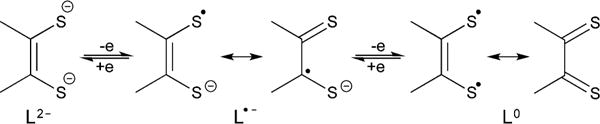

The fascinating redox chemistry demonstrated by metal–dithiolenes may largely be attributed to the non-innocent behavior of dithiolene ligands (Figure 1).3 Gray boldly proposed the likely presence of dithiolate radical anion moieties (L•−) in transition metal–dithiolene complexes more than five decades ago.13,14 The electronic structures of transition metal–dithiolene complexes were recently probed by sulfur K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), providing the strong support for the non-innocence of dithiolene ligands.8 While the radical character of the ligands in transition metal–dithiolene complexes has been extensively explored,8,15–24 free anionic dithiolene radicals are highly reactive and have only been studied computationally and by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR).25–28 Indeed, the electronic absorption spectrum of the prototype dithiolene radical anion (C2H2S2•−) was recently observed in a low-temperature matrix.29 Consequently, the captivating chemistry of anionic dithiolene radicals remains highly relevant. Herein, we report the synthesis, structure, spectra, computations,30 and reactivity of the lithium salt of anionic dithiolene radical (4•), an R2timdt-type ligand (R2timdt = disubstituted imidazolidine-2,4,5-trithione).31–36 Notably, 4• is uniquely synthesized via a carbene-based strategy and represents the first stable anionic dithiolene radical to be structurally characterized.

Figure 1.

Three oxidation levels of a dithiolene ligand.12

Reaction of N-heterocyclic carbene [NHC = :C{N(2,6-Pri2C6H3)CH}2] with an excess of elemental sulfur gives thione (1) (Scheme 1).37 However, di- and tri- sulfurization of the imidazole ring may be achieved by sulfurization of C4-metalated N-heterocyclic carbenes. The first anionic N-heterocyclic dicarbene (NHDC, 2) was synthesized by this laboratory in 2010 via C4-lithiation of a NHC ligand [L: = :C{N(2,6-Pri2C6H3)CH}2].38 Reaction of 2 with two equivalents of elemental sulfur in Et2O at low-temperature and subsequent workup in THF gives colorless disulfurized product 3 (in 73.5% yield) (Scheme 1, R = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl). Compound 3 may be purified by recrystallization in THF/hexane mixed solvent at −40 °C. Further reaction of crystalline 3 with elemental sulfur (in a 1:2 ratio) in THF at room temperature gives 4• as a crystalline purple powder in quantitative yield, which can be employed for synthesis without further purification. Notably, 4• may also be synthesized by directly reacting 2 with elemental sulfur in a 1:4 ratio (Scheme 1). However, the purity of the product 4• from the 1:4 route is relative low. Radical 4• solid is stable indefinitely under an inert atmosphere of argon. Interestingly, the transformation of 3 to 4• involves unexpected C–H bond activation. The metal-catalyzed C–S bond formation via C–H bond functionalization has received substantial attention.39 In addition, the disulfide bridge in dinuclear Ru(III) complexes has been reported to be involved in C–S bond formation.40 Notably, elemental sulfur has been utilized in copper-mediated C–S bond forming reactions via C–H activation.41 While the mechanism of the transformation of 3 to 4• remains unclear, our study reveals that this reaction requires two equivalents of elemental sulfur (Scheme 1). The corresponding 1:1 reaction only affords a mixture containing 4• and unreacted 3.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 1, 3, and 4•

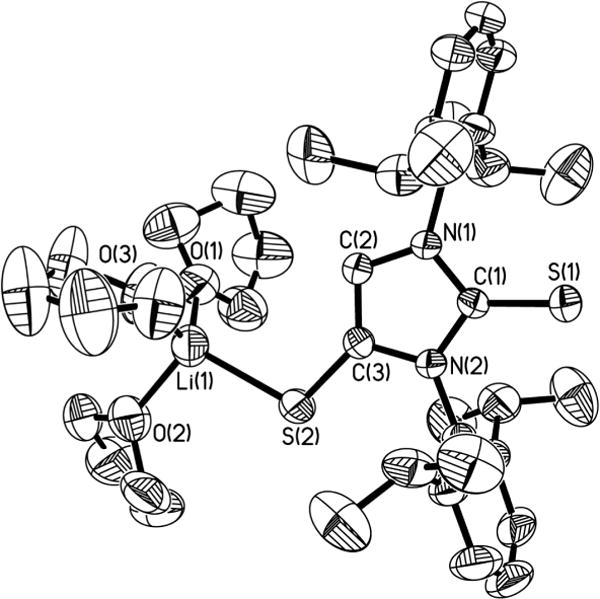

Although the 1H NMR imidazole resonance of 3 (6.14 ppm) is similar to that of 2 (6.16 ppm),38 single crystal X-ray structural analysis reveals that the two carbene carbons of 3 are sulfurized (Figure 2). The C(1)=S(1) bond distance in 3 [1.678(4) Å], comparing well to that of 1 [1.670(3) Å],42 is ca. 0.04 Å shorter than that of the C(3)–S(2) single bond in 3 [1.716(4) Å]. While the S(1) atom is terminal, the S(2) atom is bridged between the C4 carbon [i.e., C(3)] and a THF-solvated lithium cation. In addition, the Li–S bond is nearly coplanar with the imidazole ring [Li(1)–S(2)–C(3)–C(2) torsion angle = 2.1°].

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of 3. Thermal ellipsoids represent 30% probability. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (deg): C(1)–S(1), 1.678(4); C(2)– C(3), 1.355(5); C(3)–S(2), 1.716(4); Li(1)–S(2), 2.369(8); S(1)–C(1)–N(1), 128.8(3); C(2)–C(3)–S(2), 134.7(3); Li(1)–S(2)–C(3), 108.4(2).

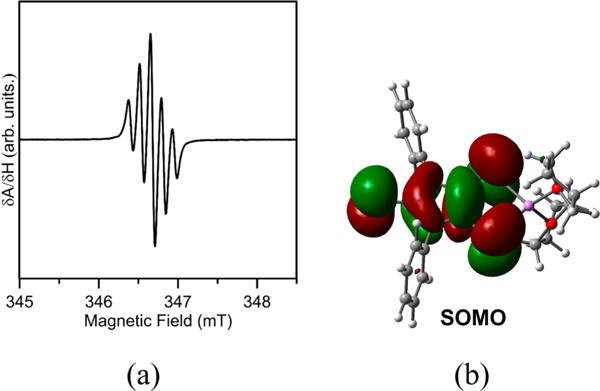

While the UV–vis absorption spectrum (Figure S1)30 of radical 4• (purple) in toluene shows two broad absorptions at 554 and 579 nm, the paramagnetic properties of radical 4• are characterized by EPR spectroscopy in THF at 298 K (Figure 3a). The EPR spectrum displays a S = 1/2 quintet (gav = 2.016) due to weak hyperfine coupling with two equivalent I = 1 14N nuclei, Aav(14N) = 3.9 MHz. Molecular orbital calculations of the simplified [4-Ph]• model suggest that the SOMO (Figure 3b) is primarily ligand-based, involving C–S π-antibonding and C–C π-bonding character. The total spin density (0.88) of the C2S2 unit in [4-Ph]• [ρ(S2) = ρ(S3) = 0.31, ρ = 0.26 for the olefinic carbons] indicates that the unpaired electron is largely localized on the C2S2 moieties.

Figure 3.

(a) Room-temperature X-band EPR spectrum of 4• in THF recorded at 9.78 GHz with a modulation amplitude of 0.02 mT and a microwave power of 0.1 mW. (b) SOMO of the simplified model [4-Ph]•.

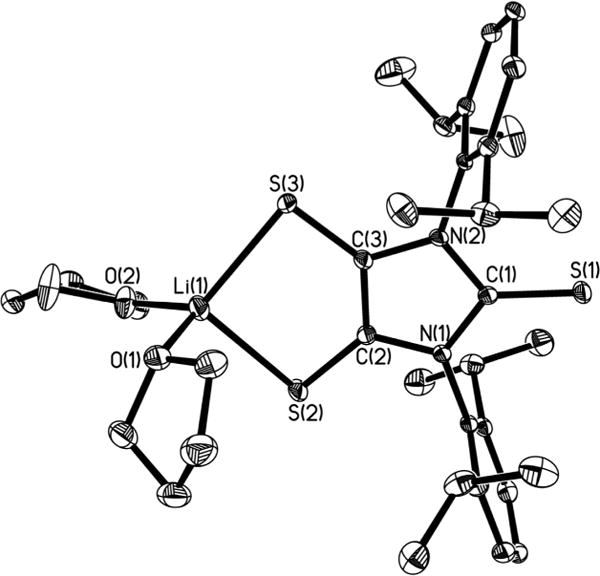

X-ray structural analysis (Figure 4) shows that a THF-solvated four-coordinate lithium cation is bound to two sulfur atoms of the dithiolene moiety in 4•, giving a five-membered LiS2C2 ring. The LiS2C2 ring of [4-Ph]• model is almost planar,30 rather than having the lithium atom obviously puckered out of plane, as observed in 4• [bend angle (η) between the MS2 (M = Li) plane and the S2C2 plane = 14.2°]. This may be due to the steric bulk of the ligand and the packing effects.43,44 The Li–S bond distances in 4• [2.442(5) Å, av], similar to that of [4-Ph]• (2.455 Å, av), is approximately 0.07 Å longer than that in monothiolate 3 [2.369(8)Å]. The Wiberg bond indices (WBIs) of the Li–S bonds in [4-Ph]• (0.28, av), coupled with the +0.66 natural charges of [(THF)2Li]+, indicate both the ionic bonding essence of the Li–S bonds and the anionic character of the [S=C{N(2,6-Pri2C6H3)-CS}2•− fragment in 4•. While comparing well with the theoretical values for [4-Ph]• (dC–C = 1.426 Å, dC–S = 1.697 Å) and for cis-C2H2S2•− (dC–C = 1.411 Å, dC–S = 1.693 Å),29 the C(2)–C(3) bond distance [1.417(3)Å] and C–S bond distances [1.677(3) Å, av] in the C2S2 moieties of 4• are in contrast to those in 3 [dC–C = 1.355(5)Å, dC–S = 1.716(4) Å] and in various dithiolates2 such as uncomplexed dithiolate ligand [i.e., (NMe4)2(C3S5), dC–C = 1.371(8) Å, dC–S = 1.724(6) Å, av]45 and silver dithiolate complex [NBu4]4[Ag-(mnt)]4 (mnt = 1,2-maleonitrile-1,2-dithiolate) [dC–C = 1.373(8) Å, dC–S = 1.736(6) Å, av].46 By comparison with those in dithiolates (L2−, Figure 1),2 the elongation of the carbon–carbon bond and concomitant shortening of the carbon–sulfur bonds observed in 4• may be attributed to the SOMO (Figure 3b) of 4•, which has C–C π-bonding and C–S π-antibonding character. The WBI values of the C(2)–C(3) bond (1.22) and C–S bonds (1.34, av) in the C2S2 moieties of 4• indicate that these bonds have a modest double bond character, which is consistent with the resonance structures of L•− in Figure 1.

Figure 4.

Molecular structure of 4•. Thermal ellipsoids represent 30% probability. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (deg): S(1)–C(1), 1.654(2); C(2)–C(3), 1.417(3); C(2)–S(2), 1.674(3); C(3)–S(3), 1.680(3); Li(1)–S(2), 2.437(5); Li(1)–S(3), 2.446(5); C(2)–C(3)–S(3), 129.54(19); Li(1)–S(2)–C(2), 93.08(14); S(2)–Li(1)–S(3), 93.31(16).

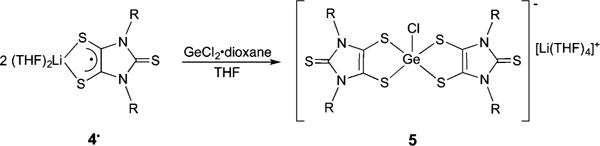

Although synthetic routes for dithiolene complexes have been reported,2 4•, as a bidentate ligand with both anionic and radical character, provides a unique platform to access a variety of dithiolene compounds. To this end, we allowed 4• to react with GeCl2·dioxane in THF (in a ratio of 2:1). The anionic chlorogermanium-bis(dithiolene) complex (5) was isolated as a dark-blue diamagnetic crystalline solid (83.3% yield) (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 5

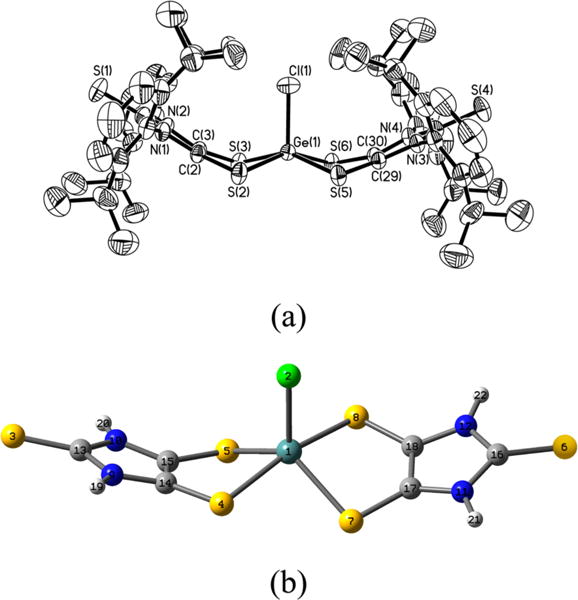

X-ray structural analysis (Figure 5a) shows that the central five-coordinate germanium atom in 5 adopts an approximate square pyramidal geometry, having four coplanar basal sulfur atoms (dS⋯S = 3.134–3.309 Å) and an apical chlorine atom. In contrast, the optimized structure (Figure 5b) of the simplified [5-H]− model (in C2 symmetry) features a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry around the germanium atom (S4–Ge1–S8 angle = 167.2°; S5–Ge1–S7 angle = 127.7°), which is comparable to that for anionic fluorogermanate [(C7H6S2)2GeF]− (Sax–Ge–Sax = 171.1°, Seq–Ge–Seq = 136.2°).47 The square pyramidal geometry about the germanium atom in 5 may well be a consequence of steric repulsion of the bulky ligands (see space-filling model of 5, Figure S2). The Ge–S bonds in 5 [2.3290(8)–2.3561(8) Å] are similar to the Ge–Seq bonds (2.361 Å), but obviously shorter than the Ge–Sax bonds (2.465 Å) in [5-H]−. It is noteworthy that, while comparing well to those of dithiolates (L2−, Figure 1),2,45,46 the olefinic C–C bonds [1.347(4) Å, av] in 5 are shorter than that in 4• [1.417(3) Å]. Meanwhile, the C–S bonds [1.719(3)–1.729(3) Å] in the C2S2 moieties of 5 are concomitantly elongated compared to those in 4• [1.677(3) Å, av]. Thus, the germanium atom in 5 may be assigned an oxidation state of +4. In addition, the C2S2Ge rings in 5 (η = 37.3°, av) are more bent than those in [5-H]− (η = 29.6°) and the C2S2Li ring in 4• (η = 14.2°). The axial Ge(1)–Cl(1) bond in 5 [2.1902(9) Å] is only slightly shorter than that in [5-H]− (2.265 Å).

Figure 5.

(a) Molecular structure of [5]−. Thermal ellipsoids represent 30% probability. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (deg): Ge(1)–Cl(1), 2.1902(9); Ge–S, 2.3290(8)–2.3561(8); C(2)–C(3), 1.349(4); C(2)–S(2), 1.724(3); C(3)–S(3), 1.727(3); S(2)–Ge(1)–Cl(1), 103.13(4); S(2)–Ge(1)–S(6), 153.89(4); S(3)–Ge(1)–S(5), 152.66(3). (b) The optimized structure of [5-H]− model in C2 symmetry.

The anionic NHDC ligand (2) may be di- and trisulfurized to give 3 and 4•, respectively. Compound 3 may be further transformed into 4• via C–H bond activation. The effective transformation of 4• to 5 suggests that 4•, as a stable monoanionic dithiolene radical, may serve as a new platform to access a variety of unexplored dithiolene chemistry. The reactivity of both 3 and 4• is being studied in this laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Science Foundation for support: CHE-1565676 (G.H.R., Y.W.) and CHE-1361178 (H.F.S.). EPR studies were supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health: R37-GM62524 (M.K.J.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b03794.

Syntheses, computations, and X-ray crystal determination, including Figures S1 and S2 and Tables S1–S12 (PDF)

Crystallographic data for compounds 3, 4•, and 5 (CIF) Crystallographic data for compound (CIF) Crystallographic data for compound 5 (CIF) (CIF)

ORCID

Henry F. Schaefer III: 0000-0003-0252-2083

Gregory H. Robinson: 0000-0002-2260-3019

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.McCleverty JA. Prog Inorg Chem. 1968;10:49–221. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiefel EI, editor. Dithiolene Chemistry: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg R, Gray HB. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:9741–9751. doi: 10.1021/ic2011748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato R. Chem Rev. 2004;104:5319–5346. doi: 10.1021/cr030655t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hine FJ, Taylor AJ, Garner CD. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:1570–1579. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabaca S, Almeida M. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:1493–1508. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garreau-de Bonneval B, Ching KIM-C, Alary F, Bui TT, Valade L. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:1457–1467. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sproules S, Wieghardt K. Coord Chem Rev. 2011;255:837–860. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sproules S. Prog Inorg Chem. 2014;58:1–144. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi A, Fujiwara E, Kobayashi H. Chem Rev. 2004;104:5243–5264. doi: 10.1021/cr030656l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holm RH, Kennepohl P, Solomon EI. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2239–2314. doi: 10.1021/cr9500390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim BS, Fomitchev DV, Holm RH. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:4257–4262. doi: 10.1021/ic010138y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray HB, Billig E. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:2019–2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stiefel EI, Waters JH, Billig E, Gray HB. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:3016–3017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokatam S, Ray K, Pap J, Bill E, Geiger WE, LeSuer RJ, Rieger PH, Weyhermüller T, Neese F, Wieghardt K. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:1100–1111. doi: 10.1021/ic061181u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huyett JE, Choudhury SB, Eichhorn DM, Bryngelson PA, Maroney MJ, Hoffman BM. Inorg Chem. 1998;37:1361–1367. doi: 10.1021/ic9703639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milsmann C, Bothe E, Bill E, Weyhermüller T, Wieghardt K. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:6211–6221. doi: 10.1021/ic900515j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milsmann C, Patra GK, Bill E, Weyhermüller T, George SD, Wieghardt K. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:7430–7445. doi: 10.1021/ic900936p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szilagyi RK, Lim BS, Glaser T, Holm RH, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9158–9169. doi: 10.1021/ja029806k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarangi R, George SD, Rudd DJ, Szilagyi RK, Ribas X, Rovira C, Almeida M, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2316–2326. doi: 10.1021/ja0665949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapre RR, Bothe E, Weyhermüller T, George SD, Wieghardt K. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:5642–5650. doi: 10.1021/ic700600r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray K, George SD, Solomon EI, Wieghardt K, Neese F. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:2783–2797. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tenn N, Bellec N, Jeannin O, Piekara-Sady L, Auban-Senzier P, Iniguez J, Canadell E, Lorcy D. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16961–16967. doi: 10.1021/ja907426s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filatre-Furcate A, Bellec N, Jeannin O, Auban-Senzier P, Fourmigue M, Vacher A, Lorcy D. Inorg Chem. 2014;53:8681–8690. doi: 10.1021/ic501293z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell GA, Zaleta M. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:2318. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell GA, Law WC, Zaleta M. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:4175–4182. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buddensiek D, Koepke B, Voss J. Chem Ber. 1987;120:575–581. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth B, Bock H, Gotthardt H. Phosphorus Sulfur Relat Elem. 1985;22:109–119. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaguchi M, Shida T. J Phys Chem A. 2016;120:3570–3577. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b03424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.See the Supporting Information for synthetic, spectral, computational, and crystallographic details.

- 31.Bigoli F, Deplano P, Devillanova FA, Lippolis V, Lukes PJ, Mercuri ML, Pellinghelli MA, Trogu EF. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1995:371–372. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bigoli F, Deplano P, Devillanova FA, Ferraro JR, Lippolis V, Lukes PJ, Mercuri ML, Pellinghelli MA, Trogu EF, Williams JM. Inorg Chem. 1997;36:1218–1226. doi: 10.1021/ic960930c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bigoli F, Deplano P, Mercuri ML, Pellinghelli MA, Pintus G, Trogu EF, Zonnedda G, Wang HH, Williams JM. Inorg Chim Acta. 1998;273:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aragoni MC, Arca M, Demartin F, Devillanova FA, Garau A, Isaia F, Lelj F, Lippolis V, Verani G. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7098–7107. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aragoni MC, Arca M, Caironi M, Denotti C, Devillanova FA, Grigiotti E, Isaia F, Laschi F, Lippolis V, Natali D, Pala L, Sampietro M, Zanello P. Chem Commun. 2004:1882–1883. doi: 10.1039/b406406b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aragoni MC, Arca M, Denotti C, Devillanova FA, Grigiotti E, Isaia F, Laschi F, Lippolis V, Pala L, Slawin AMZ, Zanello P, Woollins JD. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2003;2003:1291–1295. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei SP, Wei XG, Su XY, You JS, Ren Y. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:5965–5971. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Xie Y, Abraham MY, Wei P, Schaefer HF, III, Schleyer PvR, Robinson GH. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14370–14372. doi: 10.1021/ja106631r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen C, Zhang PF, Sun Q, Bai SQ, Hor TSA, Liu XG. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:291–314. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00239c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsumoto K, Sugiyama H. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:915–926. doi: 10.1021/ar000103m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen FJ, Liao G, Li X, Wu J, Shi BF. Org Lett. 2014;16:5644–5647. doi: 10.1021/ol5027156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srinivas K, Suresh P, Babu CN, Sathyanarayana A, Prabusankar G. RSC Adv. 2015;5:15579–15590. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steed JW, Atwood JL. Supramolecular Chemistry. 2nd. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; West Sussex, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steed JW. In: Frontiers in Crystal Engineering. 1st. Tiekink ERT, Vittal J, editors. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Chichester, UK: 2006. pp. 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breitzer JG, Smirnov AI, Szczepura LF, Wilson SR, Rauchfuss TB. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:1421–1429. doi: 10.1021/ic000999r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLauchlan CC, Ibers JA. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:1809–1815. doi: 10.1021/ic000868q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Day RO, Holmes JM, Sau AC, Holmes RR. Inorg Chem. 1982;21:281–286. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.