Abstract

Parastomal gallbladder herniation is a rare complication of enterostomies with only 6 previously reported cases. Most cases have occurred in elderly women. Patients typically presented with acute abdominal pain and the majority was managed operatively. Here, we report the clinical course of an 88-year-old female who presented with signs of sepsis and minimal abdominal symptoms. She was subsequently found to have a parastomal gallbladder herniation and Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Given the patient's multiple comorbidities, she was managed nonoperatively with manual reduction of the parastomal hernia and antibiotics.

Keywords: Hernia, Gallbladder, Parastomal hernia, Colostomy, Visceroptosis

Introduction

Parastomal hernias are frequent complications of enterostomies [1], [2]. Risk factors for developing parastomal hernia development include advanced age, high body mass index, smoking, and presence of colostomy rather than ileostomy [3], [4]. Gallbladder herniation at any site is rare, and only a few cases have been reported in the literature [5]. Among the 6 previously reported cases of parastomal gallbladder herniation, the majority presented with progressive abdominal pain and preserved bowel function [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. The only reported case managed without urgent cholecystectomy was treated conservatively because of patient's advanced age, cardiovascular disease, and patient preference [4]. Here, we report the case of a patient with a parastomal gallbladder hernia that was discovered during a sepsis work-up and was treated conservatively.

Case report

An 88-year-old female presented from an assisted living facility with fevers and worsening abdominal pain. Eleven months before her presentation, she had undergone a sigmoid colectomy for rectal prolapse with a transverse loop colostomy because of repeated rectal manipulation. Other comorbidities included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and a 35 pack-year smoking history. She denied obstructive symptoms including feeling nauseous or vomiting, decreased oral intake, and decreased colostomy output. On presentation, she was febrile to 102.4 F, tachycardic to 111 beats per minute, and hypertensive to 162/88 mm Hg. Physical examination in the emergency department only revealed mild tenderness to abdominal palpation bilaterally. Her laboratory values were notable for a white blood cell count of 18.3 × 103/μL, and a normal urine analysis and chest x-ray. Liver function tests showed normal total bilirubin levels (0.9 mg/dL) and mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase (135 U/L), aspartate transaminase (49 U/L), and alanine transaminase (63 U/L) levels. Blood cultures were drawn from two separate sites, and the patient was started on empiric piperacillin and/or tazobactam. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was ordered, given her clinical presentation of abdominal pain associated with sepsis.

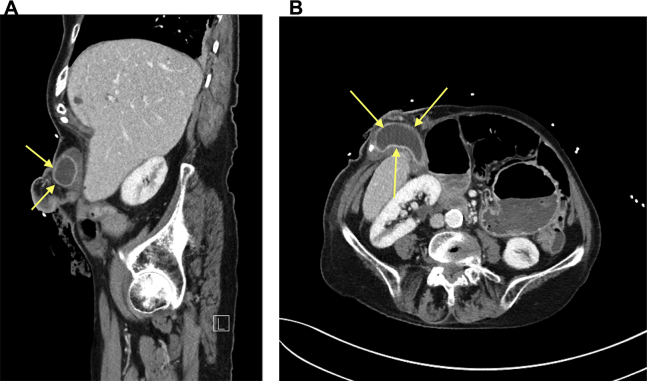

CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a parastomal gallbladder hernia (Fig. 1A and B). The gallbladder wall was 6 mm thick and appeared chronically inflamed with avid mural enhancement. It was distended with maximum anteroposterior length of 5.59 cm and maximum transverse width of 5.94 cm. There was only mild biliary duct dilation, decreased from previous imaging. The surgical team was consulted, and they identified and reduced the parastomal hernia. The patient was placed on bowel rest with a nasogastric tube for decompression. Cholecystectomy was not recommended because of the patient's age, poor functional status, and clinical improvement on antibiotics [10]. Blood cultures were both positive for Klebsiella pneumoniae, presumably secondary to cholecystitis, that was sensitive to ceftriaxone, and the antibiotic regimen was narrowed accordingly. Repeat blood cultures drawn one day after the patient's admission showed no growth after 5 days. The patient's white blood count normalized the following day, her nasogastric tube was removed, and she was discharged to a nursing facility on a 14-day course of amoxicillin and/or clavulanate.

Fig. 1.

(A) Sagittal computed tomography (CT): contrast enhanced CT showing a thick-walled and chronically inflamed-appearing gallbladder in the parastomal defect (arrows). (B) Axial CT: gallbladder extending into the parastomal defect (arrows).

Discussion

An 88-year-old female presented to the emergency department 11 months after sigmoid colectomy with transverse loop colostomy with signs of sepsis. Subsequent workup revealed K. pneumoniae bacteremia presumably secondary to a parastomal hernia containing a thick-walled and chronically inflamed-appearing gallbladder. K. pneumoniae is among the most common isolates from bacteremia secondary to cholecystitis [11]. In our case, all other sources of bacteremia had been excluded besides the parastomal gallbladder hernia. As the hernia was manually reducible and the patient responded well to antibiotic treatment, conservative management was chosen over cholecystectomy. In addition, surgery was not recommended given the patient's poor functional status and multiple comorbidities.

Most previously reported cases of parastomal gallbladder herniation had abdominal pain as the predominant presenting symptom [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Our patient may have had fewer localizing symptoms because of advanced age and chronic debilitation. Significant nausea and vomiting is uncommon among cases of gallbladder herniation and is more suggestive of bowel herniation, which can co-occur with gallbladder herniation [7]. Our patient had no change in appetite or gastrointestinal symptoms before admission. Minimal derangement in liver function tests were detected in this case consistent with previous reports [4], [5], [9].

Although many abdominal wall hernias can be diagnosed clinically, CT can be an important aid in diagnosis [12]. Imaging can also help delineate the herniated structures when nonintestinal hernia contents are suspected. In our case, the initial physical examination in the emergency department did not detect a parastomal hernia, and the CT scan was critical to establish the diagnosis and determine appropriate management. Gurmu et al [13] reported how the detection of parastomal hernias on physical examination could be particularly difficult. Baucom et al [14] found that CT was superior to physical examination even for detecting simple incisional hernias, particularly in obese patients. CT has been suggested as a possible gold standard for diagnosis of incisional hernias [15]. Furthermore, CT can assist in identifying complications of abdominal wall hernias including bowel obstruction, strangulation, and traumatic injury [12]. Most previously reported cases of parastomal gallbladder herniation included CT imaging as part of the diagnostic work-up [4], [5], [6], [8], although the gallbladder's presence in the hernia sac was identified intraoperatively in one case [9] and by abdominal radiograph in another [7]. The gallbladder may be absent from its normal anatomic location or extend from the gallbladder fossa into the parastomal hernia. In this setting, CT can also aid in evaluating the gallbladder wall thickness, presence of mural or luminal gas, and presence of stones [8].

Gallbladder herniation is a rare occurrence because of the gallbladder's relatively fixed position in the upper right quadrant. Multiple factors in elderly patients predispose to gallbladder herniation, such as loss of visceral fat and elastic tissue, shrinkage of the liver, and ultimately lengthening of the gallbladder's mesentery [16]. The average age at presentation among previous reports of gallbladder herniation is 70.2 years [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], similar to our case report. Increased visceroptosis among females is also believed to contribute to loosening of the gallbladder's mesentery [17]. Indeed, 5 of the previous 6 reported cases of parastomal gallbladder herniation occurred in women.

In summary, this is the first reported case of parastomal gallbladder herniation complicated by sepsis, which was successfully treated conservatively. Abdominal pain was not a prominent feature of presentation in this case unlike previous cases of parastomal gallbladder herniation. Our patient was an elderly female consistent with initial trends among reported cases of parastomal gallbladder herniation. Conservative management was opted for after successful manual reduction of the hernia and treatment of bacteremia with antibiotics because the patient was a poor surgical candidate. This case report should alert physicians that parastomal gallbladder herniation may occur without significant abdominal symptoms in the elderly, and that conservative management may be pursued in poor surgical candidates.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the clinical staff at the Southern Arizona Veterans Affairs Health Care System for their assistance in patient care.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Temple B., Farley T., Popik K., Ewanyshyn C., Beyer E., Dufault B. Prevalence of parastomal hernia and factors associated with its development. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016;43:489–493. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandsma H.-T., Hansson B.M.E., Aufenacker T.J., van Geldere D., Lammeren F.M.V., Mahabier C. Prophylactic mesh placement during formation of an end-colostomy reduces the rate of parastomal hernia: short-term results of the Dutch PREVENT-trial. Ann Surg. 2017;265:663–669. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funahashi K., Suzuki T., Nagashima Y., Matsuda S., Koike J., Shiokawa H. Risk factors for parastomal hernia in Japanese patients with permanent colostomy. Surg Today. 2014;44:1465–1469. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0721-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia R.M., Brody F., Miller J., Ponsky T.A. Parastomal herniation of the gallbladder. Hernia J Hernias Abdom Wall Surg. 2005;9:397–399. doi: 10.1007/s10029-005-0340-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.To H., Brough S., Pande G. Case report and operative management of gallbladder herniation. BMC Surg. 2015;15:72. doi: 10.1186/s12893-015-0056-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez-Artacho M., Boisset G., Taoum C., Navarro F. Complicated parastomal hernia as a clinical presentation of a gallbladder hydrops. Cirugia Espanola. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2016.05.019. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rashid M., Abayasekara K., Mitchell E. A case report of an incarcerated gallbladder in a parastomal hernia. 2009. https://ispub.com/IJS/23/2/5548 Internet J Surg [Internet]. [cited 2017 Mar 26];23. Available at: Accessed April 20, 2017.

- 8.Rosenblum J.K., Dym R.J., Sas N., Rozenblit A.M. Gallbladder torsion resulting in gangrenous cholecystitis within a parastomal hernia: findings on unenhanced CT. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7:21–25. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v7i12.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St Peter S.D., Heppell J. Surgical images: soft tissue. Incarcerated gallbladder in a parastomal hernia. Can J Surg J Can Chir. 2005;48:46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGillicuddy E.A., Schuster K.M., Barre K., Suarez L., Hall M.R., Kaml G.J. Non-operative management of acute cholecystitis in the elderly. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1254–1261. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo C.H., Changchien C.S., Chen J.J., Tai D.I., Chiou S.S., Lee C.M. Septic acute cholecystitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:272–275. doi: 10.3109/00365529509093276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguirre D.A., Santosa A.C., Casola G., Sirlin C.B. Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at multi-detector row CT. Radiogr Rev Publ Radiol Soc N Am Inc. 2005;25:1501–1520. doi: 10.1148/rg.256055018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurmu A., Matthiessen P., Nilsson S., Påhlman L., Rutegård J., Gunnarsson U. The inter-observer reliability is very low at clinical examination of parastomal hernia. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baucom R.B., Beck W.C., Holzman M.D., Sharp K.W., Nealon W.H., Poulose B.K. Prospective evaluation of surgeon physical examination for detection of incisional hernias. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:363–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keersmaecker G.D., Beckers R., Heindryckx E., Kyle-Leinhase I., Pletinckx P., Claeys D. Retrospective observational study on the incidence of incisional hernias after reversal of a temporary diverting ileostomy following rectal carcinoma resection with follow-up CT scans. Hernia. 2016;20:271–277. doi: 10.1007/s10029-015-1419-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHenry C.R., Byrne M.P. Gallbladder volvulus in the elderly. An emergent surgical disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:137–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb05482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakao A., Matsuda T., Funabiki S., Mori T., Koguchi K., Iwado T. Gallbladder torsion: case report and review of 245 cases reported in the Japanese literature. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:418–421. doi: 10.1007/s005340050143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]