Abstract

Advanced capabilities in electrical recording are essential for the treatment of heart-rhythm diseases. The most advanced technologies use flexible integrated electronics; however, the penetration of biological fluids into the underlying electronics and any ensuing electrochemical reactions pose significant safety risks. Here, we show that an ultrathin, leakage-free, biocompatible dielectric layer can completely seal an underlying layer of flexible electronics while allowing for electrophysiological measurements through capacitive coupling between tissue and the electronics, and thus without the need for direct metal contact. The resulting current-leakage levels and operational lifetimes are, respectively, four orders of magnitude smaller and between two and three orders of magnitude longer than those of any other flexible-electronics technology. Systematic electrophysiological studies with normal, paced and arrhythmic conditions in Langendorff hearts highlight the capabilities of the capacitive-coupling approach. Our technology provides a realistic pathway towards the broad applicability of biocompatible, flexible electronic implants.

Tools for spatially mapping electrical activity on the surfaces of the heart are critically important to experimental cardiac electrophysiology and clinical therapy. The earliest systems involved micro-electrode arrays on flat, rigid substrates, with a focus on recording cardiac excitation in cultured cardiomyocytes and mapping signal propagation across planar cardiac slices1–5. More recent technologies exploit flexible arrays, in formats ranging from sheets, to baskets, balloons, ‘socks’ and integumentary membranes, with the ability to integrate directly across large areas of the epicardium and endocardium in beating hearts6–10. The most sophisticated platforms of this type include an underlying backplane of thin, flexible active electronics that performs local signal amplification and allows for multiplexed addressing11,12. This latter feature is critically important because it enables scaling to high density, high speed measurements, in regimes that lie far beyond those accessible with simple, passively addressed systems without integrated electronics. The measurement interface associated with all such cases relies on thin electrode pads in direct physical contact with the tissue, where electrical signals transport through via-openings to the electronics. Although this approach has some utility, bio-fluids can readily penetrate through the types of polycrystalline metal films used for the electrodes. Resultant leakage currents from the underlying electronics can cause potentially lethal events such as ventricular fibrillation (VF), and cardiovascular collapse13,14; they also lead to degradation of the Si electronics and catastrophic failure of the measurement hardware. The electrochemical reaction with the electrolyte at the metal/tissue interface will also yield bio-corrosion of metal films15. By consequence, devices of with such designs are inherently unsuitable for human use, even in surgical contexts or other acute applications. Similar considerations prevent their application in any class of implant16–18.

The results presented here provide a robust and scalable solution to these challenges by eliminating all direct metal interfaces and replacing them with capacitive sensing nodes integrated on high performance, flexible silicon electronic platforms for multiplexed addressing. Specifically, an ultrathin, thermally-grown layer of silicon dioxide covers the entire surface of the system, to serve both as a dielectric to enable direct capacitive coupling to the semiconducting channels in arrays of silicon nanomembrane (Si NM) transistors and as a robust, biocompatible barrier layer to prevent penetration of bio-fluids. The co-integration of active electronic circuits affords built in signal conditioning and processing, as well as scalability via multiplexed addressing19–25. Although capacitive methods for sensing26–28 and rigid platforms of large-scale active microelectrodes29–32 are known, our work combines two features that, viewed either individually or collectively, are important advances in technology for electrophysiological mapping at the organ level in living biological systems: (1) use of an ultrathin thermally grown layer of silicon dioxide for capacitive sensing that simultaneously provides high-yield, defect-free encapsulation layers with long-term stability in bio-fluids; (2) combination of high fidelity capacitive sensing, long-term stability and mechanical flexibility in a fabrication process that yields thin active electronics with robust operation on dynamically evolving curved surfaces of biological tissue, as demonstrated in cardiac mapping on beating hearts. The technology introduced here is the first to incorporate all of the key features needed for use in high speed, high resolution cardiac electrophysiology: (1) large area formats with integrated active electronics for multiplexing and signal amplification on a per channel level, (2) thin, flexible device mechanics for integration and high fidelity measurement on the curved, moving surfaces of the heart, (3) cumulative levels of leakage current to the surrounding tissue that remain well below 1 μA (per ISO 14708 1:2014 standards for implantable devices), for safe operation, (4) long-lived, thin, bendable bio-fluid barriers as perfect, hermetic sealing of the underlying electronics for stable, reliable function and (5) biocompatible interfaces for long-term use, without direct or indirect contact to traditional electronic materials. Detailed studies of the materials and the combined electrical and mechanical aspects of the designs reveal the key features, and advantages, of this type of system. Application to epicardial mapping of ex vivo Langendorff heart models further quantitatively validates the capabilities in various contexts of clinical relevance. The resulting high levels of safety in operation and long-term, long-term stable measurement capabilities create unique, compelling opportunities in both cardiac science and translational engineering.

Results

Capacitively coupled silicon nanomembrane transistors as active sensing nodes

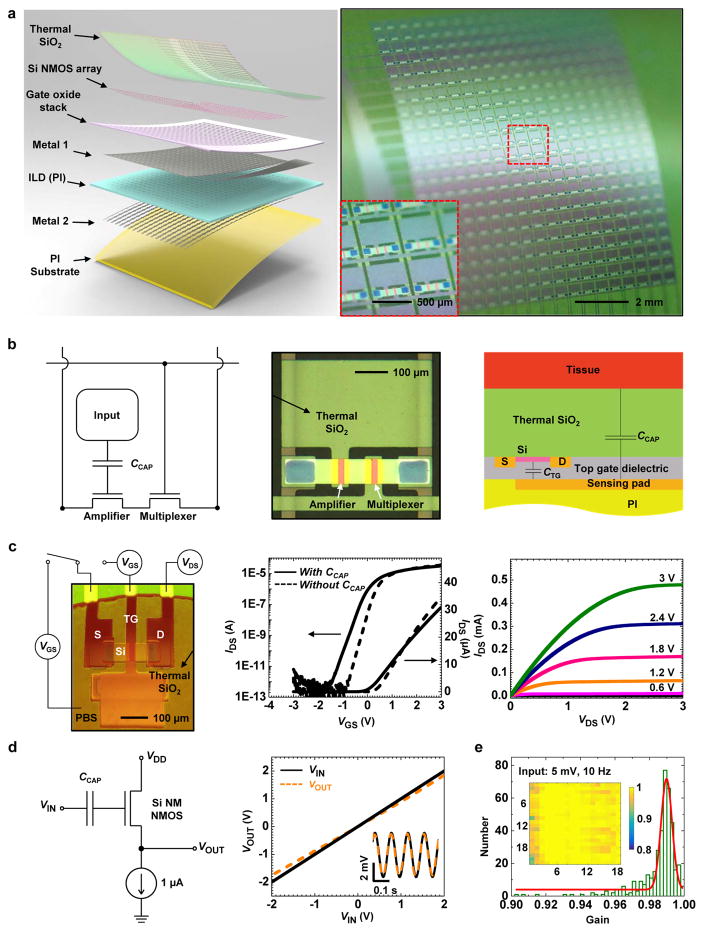

The overall system consists of 396 multiplexed capacitive sensors (18 columns, 22 rows), each with dimensions of 500 μm × 500 μm, as shown in Fig. 1a, distributed uniformly over a total area of 9.5 mm × 11.5 mm. Each sensor consists of two underlying Si NM transistors, one of which connects to a metal pad from its gate electrode (Fig. 1a and b). A layer of thermally grown silicon dioxide (900 nm, SiO2) covers the entire top surface of the system (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1–4). This ultrathin (comparing to the thickness of the layers used previously for encapsulation33–35) thermal SiO2 layer serves not only as the dielectric for capacitive coupling of adjacent tissue to the semiconducting channels of the associated Si NM transistors, but also as a barrier layer that prevents penetration of bio-fluids to the underlying metal electrode and associated active electronics. The fabrication begins with definition of 792 Si n-channel metal-oxide semiconductor (NMOS) transistors on a silicon on insulator (SOI) wafer. A sequence of deposition, etching and photolithographic patterning steps forms the necessary dielectric and metal layers for the interconnects and sensing electrodes. Bonding a layer of polyimide on top of this electronics yields a thin, flexible system upon removal of the silicon wafer. Here, the buried oxide (Box) layer of the SOI wafer serves as the capacitive interface and encapsulation layer. Detailed information on the device fabrication can be found in Methods, Supplementary note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1. Supplementary Fig. 2 and 3 show optical images at various stages of the fabrication and a corresponding cross sectional schematic illustration of the final device, respectively. This fabrication process is capable of scaling up to the largest silicon wafers available (currently 450-mm diameter), allowing for systems that provides full area coverage across most of the internal organs of the human body.

Figure 1.

Capacitively coupled silicon nanomembrane transistors (covered by a thermal SiO2 layer) as active sensing nodes in actively multiplexed flexible electronic system for high resolution electrophysiological mapping. (a) Exploded-view schematic illustration (left) and a photograph (right) of a completed capacitively-coupled flexible sensing system with 396 nodes in a slightly bend state. The arrows in the left illustration highlight the key functional layers. Inset on the right shows a magnified view of a few nodes. (b) Circuit diagram for a node in this capacitively coupled array, with annotations for each component (left), and an optical microscope image of the cell (middle). A schematic of the circuit cross-section (right) illustrates the mechanism for capacitively coupled sensing through a thermal SiO2 layer to an underlying transistor. (c) Demonstration of capacitively coupled sensing using a test transistor (left), and its transfer (middle) and output (right) characteristics. The supply voltage (VDD) was set to 3 V for in vitro bench testing, while it was a feedback from output signal during ex vivo measurements (Supplementary Fig. 16). The transfer characteristics correspond to cases with and without capacitive coupling (channel width W=80 μm, effective channel length Leff=13.8 μm, VDS=0.1 V), in both semi-log and linear scale). Dashed curves depict characteristics measured by directly biasing the gate metal; the solid curves follow result from biasing a droplet of saline solution (red, on the left frame) in contact with the thermal SiO2 layer above the transistor and the gate metal pad. (d) Validation of capacitively coupled sensing from a single-transistor source-following amplifier, with a schematic of the circuit (left), and its output characteristics (right). Inset in the right figure shows the output characteristics with an AC input of 5 mV at 10 Hz. (e) Histogram (with fitting to a Gaussian lineshape) of gain values from all 396 nodes of a typical systems. The results indicate 100% yield and near-unity average gain. The inset shows a spatial map of the gain values.

As presented in the equivalent circuit, top and cross sectional views of Fig. 1b, each sensor includes an amplifier and a multiplexer, with capacitive input. The amplifier consists of a Si NM transistor (channel length Leff = 13.8 μm, width W = 80 μm, thickness t = 50 nm), with a gate that extends to a large metal pad (270 μm × 460 μm). The thermal SiO2 layer above the transistor and the metal pad physically contacts adjacent tissue during operation. The tissue/SiO2/gate metal pad forms a large capacitor (CCAP, tissue/SiO2/gate metal pad) that couples with the gate that drives the transistor channel. This directly couples to the semiconductor channel of the amplifier, bypassing the effects of capacitance in the wiring to remote electronics, as an important distinction between the architecture presented here and traditional, passive capacitive sensors28,36. This direct coupling provides immediate signal amplification and eliminates signal cross-talk along the pathway. Previously reported nanowire bio-sensors21,37 rely on similar coupling schemes, although difficulties in scaling prevent their use in the types of large-scale, multiplexed arrays introduced here. The capacitance, CCAP, is configured to be over one order of magnitude larger than the top gate capacitance (CTG) of the transistor, thereby prevent forming a voltage divider and attenuating the signal. This design is important for high performance signal amplification and low noise levels28. Detailed electrical models of the operation are in the Methods section. The sensing system also utilizes an active multiplexing circuitry design similar that described elsewhere12, where the electrical signal from the tissue at each given node in the array is selected in a rapid time sequence by the multiplexing transistors (with the same dimensions as the amplifier transistor) for external data acquisition. Additional details are in Methods.

Figure. 1c illustrates the principle of the capacitive coupling to a Si NM transistor. Electrically biasing a droplet of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution placed in contact with the SiO2 layer causes coupling to the gate pad of the transistor (while the gate pad was not directly biased), thereby allowing measurement of the transfer characteristic in a manner that simulates the effects of electrical potential generated from the contacting tissue (Fig. 1c, left and middle). The resulting transconductances, threshold voltages, and subthreshold swings are similar to those measured by directly biasing the gate pad, thereby validating the capacitively coupled sensing design. (The minor discrepancies in the subthreshold swing and transconductance arise from slight differences in the overall capacitance to the channel.) The capacitively coupled transistor exhibits an on/off ratio of ~107 and a peak effective electron mobility of ~800 cm2/V.s (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 5), as calculated from standard field effect transistor models (see Methods). Figure 1c (right) shows the output characteristics, consistent with Ohmic source/drain contacts and well-behaved current saturation. This high performance operation is critically important for high fidelity amplification and fast, multiplexed addressing.

The operation and output characteristics of the amplifier appear in Fig. 1d. Here, a current sink and a single-stage Si NM transistor with capacitively coupled input forms a common drain amplifier (source follower). As a result of the large capacitive coupling, this circuit offers high voltage gain (0.97, where 1 is the ideal value) for both DC (-2 to 2 V) and AC (5 mV, 10 Hz) inputs (Fig. 1d, right), where the gain corresponds to the ratio between the output and input voltages (VOUT/VIN). The presence of the thermal SiO2 layer yields an ultra-high input impedance measurement interface (~2.6 GΩ per sensing node at 10 Hz, Supplementary Fig. 6), and nearly perfect encapsulation of the electronics from the surroundings. This high input impedance at the SiO2/tissue interface transfers into a low output impedance (~855 Ω per sensing node, detailed calculation in Methods) via the source follower circuit’s current gain. Additional circuit level improvement such as input capacitance neutralization and circuit reference grounding, with reduced thermal SiO2 thickness can further enhance the recording quality of bio-potentials38.

Such sensing systems can be constructed with excellent uniformity in electrical responses across all sensing nodes. Figure 1e shows a histogram plot of the gain measured on all nodes of a 396-channel sensing matrix; the yield is 100% and the average gain is 0.99 (minimum: 0.9, maximum: 1, with a standard deviation of 1.12 × 10–4). The yield here defines the number of working (with gain above 0.6) sensing nodes divided by the total sensing nodes on the array. In testing and ex vivo experiments, the 22 row select signals cycle at 25 kHz, yielding a sampling rate of 1136 Hz per node. This rate can be further increased by improving the multiplexing rate in the back-end data acquisition (DAQ) system.

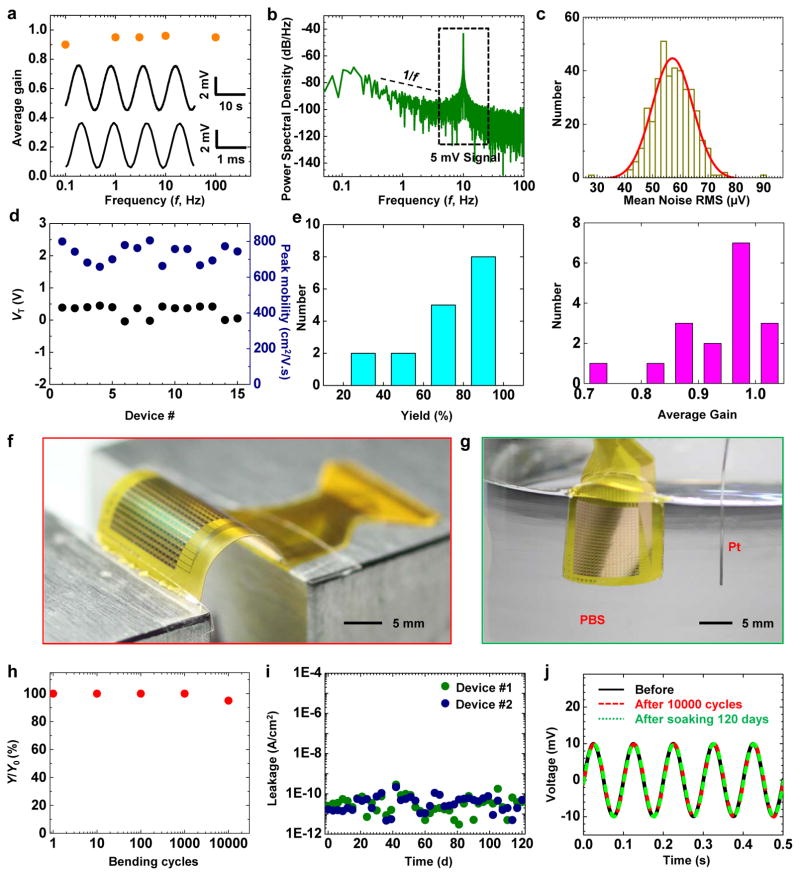

In vitro assessment of electrical performance

The performance of the capacitively coupled active sensing nodes is stable across a broad time dynamic range. Figure 2a shows high gain, low noise measurements for input signal frequencies between 0.1 and 100 Hz, with similar or better performance than simple, directly coupled metal sensing interfaces (Supplementary Fig. 7). The power spectral density (PSD) of the output signal, computed from the Fourier transform of the auto-correlation function, describes its frequency behavior. As an example, the PSD of the noise (Fig. 2b, when measuring with a 5 mV, 10 Hz sine-wave input) indicates expected ~1/f behavior at low frequencies, consistent with circuit models (see Methods). Figure. 2c displays a 396-channel sensing system with mean noise as low as ~ 55 μV and SNR over 42 dB (also see Supplementary Fig. 8), and excellent uniformity across the entire device. The transistor mobility, the sensing node gain, and the array yield are also superior, likely due to the better interface from Si and thermal SiO2. Statistics on the test transistor threshold voltage, mobility, array yield and average gain from different devices show very small sample to sample and batch to batch variations (Fig. 2d and e). Mechanical bending tests and in vitro soak tests highlight the flexibility and robustness of the system (Fig. 2f and g). For ~5 mm bending radii, the finite element analysis (FEA, Supplementary Fig. 9) indicates that the strain induced in the Si and top SiO2 layers are less than 0.025%, far below their fracture limits (~1%). The device performance remains unchanged in the bent state and does not vary after bending to a radius of 5 mm for 1, 10, 100, 1000, and 10000 cycles (Fig. 2h). Infrared imaging also reveals that there is no apparent increase in temperature associated with operation of the device (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Figure 2.

In vitro assessment of electrical performance. (a) Average gain of a representative capacitively coupled transistor as a function of the input frequency (f) from 0.1 to 100 Hz. Inset shows the responses from this sensor node at 0.1 Hz (top) and 100 Hz (bottom), after band-pass filtering (0.05–568 Hz). (b) Power spectral density of a 5 mV AC signal at 10 Hz measured at a representative node, showing a typical 1/f relationship at low frequency. The input was a sine-wave of 5 mV at 10 Hz. (c) Histograms of noise (with Gaussian fitting) measured from all 396 nodes of the device in Fig. 1c. (d) Statistics of the threshold voltage (VT) and peak effective mobility (μeff) of test transistors from 15 different arrays. (e) Statistics of yield (left) and gain (right) of 17 capacitively coupled, active sensing 18×22 electrode array. (f) Image of a device during a mechanical bending test. (g) Image of a device completely immersed in a saline solution, during a soak test. (h) Yield (Y, defined as the number of working nodes divided by the total number of nodes) as a function of cycles of bending to 5 mm bend radius, showing minimal changes up to 10000 cycles. (i) Electrical leakage current of 2 devices during soak testing. Minimal leakage appears over a period of 120 days at 37 °C. (j) Response of a representative node to a sine wave input (at 10 Hz) before, after 10000 cycles bending, and after saline immersion for 120 days.

The system also demonstrates outstanding stability of continuous operation when completely immersed in saline solution and bio-fluids, due to the thermal SiO2 encapsulation. Figure 2g depicts the set-up for the soak test, where phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution simulates the cardiac bio-fluid. Evaluations involve application of a 3 V DC bias between the sensing system and a Pt reference electrode throughout the test, at a temperature of 37 °C. The leakage current remains lower than 10−9 A/cm2 for at least 120 days (measured up to date) for 2 devices (Fig. 2i). Figure 2j shows the device response to a 10-Hz sine wave input, before and after the bending and soaking experiments. All indications are consistent with reliable, invariant operation associated with conditions that mimic those for in vivo cardiac applications. The most compelling demonstrations are in leakage levels that are factors of 10,000 smaller than those of previous related cardiac mapping technologies (factors of 1000 smaller than the standard of safety limit for active implantable medical device in ISO 14708 1:2014, 1 μA). Compared to previously reported devices with lifetimes of only a few hours in soak tests11, the operational lifetimes here are between two and three orders of magnitude longer, with interfaces that consist of a uniform layer of a well-established material (thermal silicon dioxide) in traditional implants. This unprecedented device longevity highlights the pin hole free nature and robustness of the thermal SiO2 layer, which is unachievable with films deposited using conventional methods.

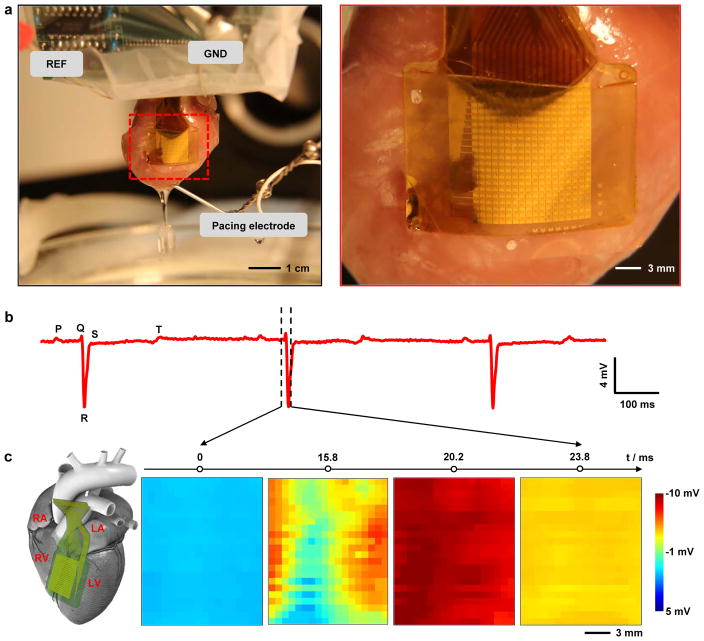

Cardiac mapping in animal heart models

Experiments that validate the function involve recording of unipolar voltage signals from all 396 nodes on multiple ex-vivo Langendorff perfused rabbit hearts39. Figure 3a shows a system placed on the anterior aspect of the heart with equal overlap on the right and left ventricles. The device conformally covers the curvilinear surface of the heart. Although capillary forces associated with the moist cardiac surface can fixate the device in place, the use of a thin Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) film wrapped around the heart further enhanced the robustness of the mechanical coupling. Samples of representative single node voltage tracings during sinus rhythm are in Fig. 3b. Clear components, similar to the P wave, QRS complex, and T wave in clinical electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings, are apparent. The low noise levels of are consistent with the in vitro results (Supplementary Fig. 11). The average heart beats at ~125 beats per minute. Attaching the device on heart does not interfere with the heart’s rhythm, based on experimental observations (Supplementary Fig. 12). The slowing of the sinus rhythm rate can be attributed to normal heart deterioration that results from the use of a blood substitute in the ex vivo Langendorff perfused model. High definition spatial temporal electrophysiology mapping results from plotting the signals from all 396 nodes as a function of time. Spatial voltage maps of all nodes at four sequential time points appear in Fig. 3c, corresponding to phase 4 to phase 1 in the cardiac action potential (dashed lines in Fig. 3b illustrate the time window where Fig. 3c is taken). The wave of cardiac activation approaches the center of the anterior aspect of the heart from both the left and right sides, which matches well the physical location of the device. The extracted conduction velocities (0.9506 ± 0.3340 mm ms−1) are close to values inferred from optical data (0.8124 ± 0.3438 mm ms−1) as described in the following, for the 300 ms cycle length (Supplementary Fig. 13). This same technology platform is important not only for cardiac applications (both ex vivo and in vivo, as demonstrated in Supplementary note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 14), but also for high speed mapping of electrophysiology of other organ systems, including those that exhibit much smaller changes in voltage, and for use as implants in live animal models. Successful in vivo recording from rat auditory cortex (Supplementary note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 15) demonstrates these capabilities.

Figure 3.

High density cardiac electrophysiological mapping on ex vivo rabbit heart models. (a) A photograph of a flexible capacitively coupled sensing electronic system on a Langendorff-perfused rabbit heart (left). Magnified view, showing conformal contact of the device to the cardiac tissue, via the action of surface tension (right). (b) Representative single voltage trace from the electrode array without external pacing. Signatures related to the P, Q, R, S, and T waves in ECG traces, can be identified from the recordings. (c) Representative voltage data for all electrodes at four time points (indicated in B), showing normal cardiac wave-front propagation. The progress of the cardiac wave is consistent with the physical location of the array on heart, as illustrated in the diagram on the left (RA, LA, RV and LV stands for right atrium, left atrium, right ventricle, and left ventricle respectively).

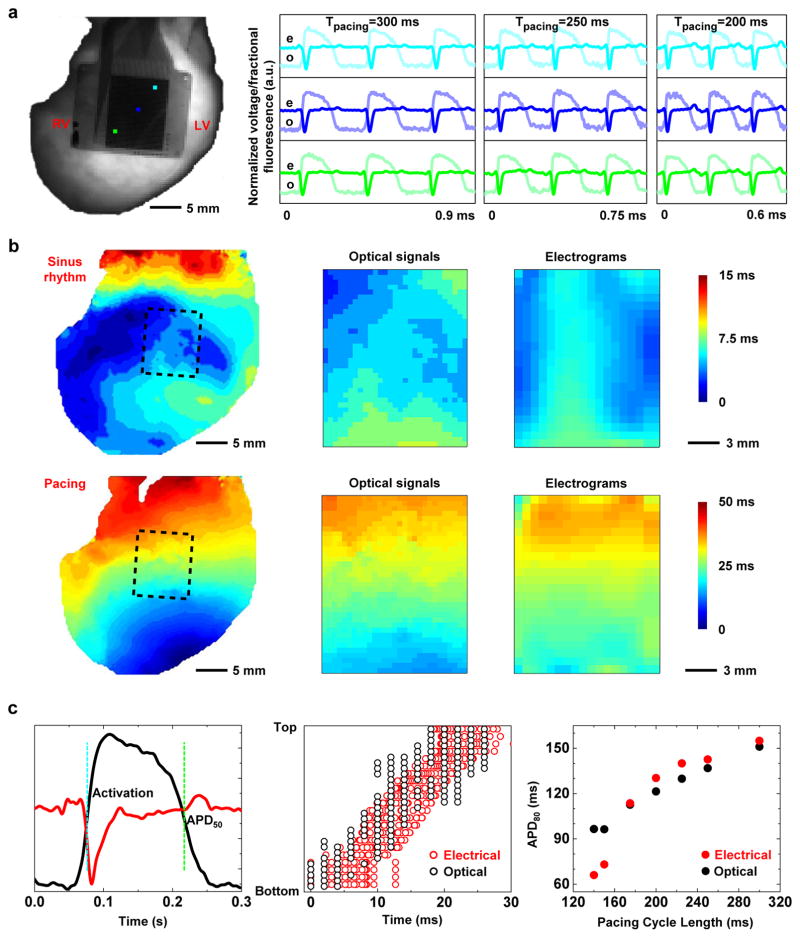

Comparison with fluorescence imaging

The optical transparency of the system in the spaces between the metal electrodes and transistors allows validation of electrical measurements by means of simultaneous optical mapping40. In particular, comparison of electrical and optical recordings provides a robust method for establishing morphological criteria for phenomenon like activation and repolarization. Figure 4a shows a three-beat comparison of optical and electrical signals at three distinct pacing cycle lengths. Representative optical action potentials show an adequate signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for this comparison despite the dense nature of the sensing circuits. Interpolated activation maps of both data types reveal a strong association during both sinus rhythm (Fig. 4b, top) and pacing (Fig. 4b, bottom). Close observation (Fig. 4c, left) of the two signals types indicates a close correspondence of key morphologies associated with activation (QRS complex in electrogram vs. (dV/dt)max in optical signal, where V is the optical signal, and t is the time) and repolarization (T wave in electrogram vs. APD90 in optical signal, where APD90 stands for the action potential duration at 90% of repolarization). Strong correlations in activation (Fig. 4c, middle) and repolarization (Fig. 4c, right) are also apparent. The electrical and optical recordings also demonstrate good accuracy from the equivalence test (Supplementary Fig. 16).

Figure 4.

Comparison of electrical mapping with optical fluorescence recording. (a) Representative electrical and optical signals captured simultaneously on a Langendorff-perfused rabbit heart at multiple cycle lengths (300, 250, and 200 ms). (b) Interpolated spatial activation maps derived from these data. Top row shows activation as measured during sinus rhythm. The bottom row corresponds to 300 ms ventricular pacing. The activation maps from left to right are optical signals from the whole heart, optical signals from the device area, and electrical signals respectively. The dashed boxes in the whole heart illustrations depict the device area. (c) Comparison of activation and repolarization measurements in a single simultaneously measured electrical and optical signals. Left figure highlights a quantitative comparison of electrical and optical signals during one depolarization/repolarization cycle. Center figure shows the comparison of activation times measured across all electronic nodes and corresponding optical field of view. Right figure shows the comparison of optical and electrical restitution curves measured at various cycle lengths (300, 250, 225, 200, 175 ms).

Study of ventricular fibrillation (VF)

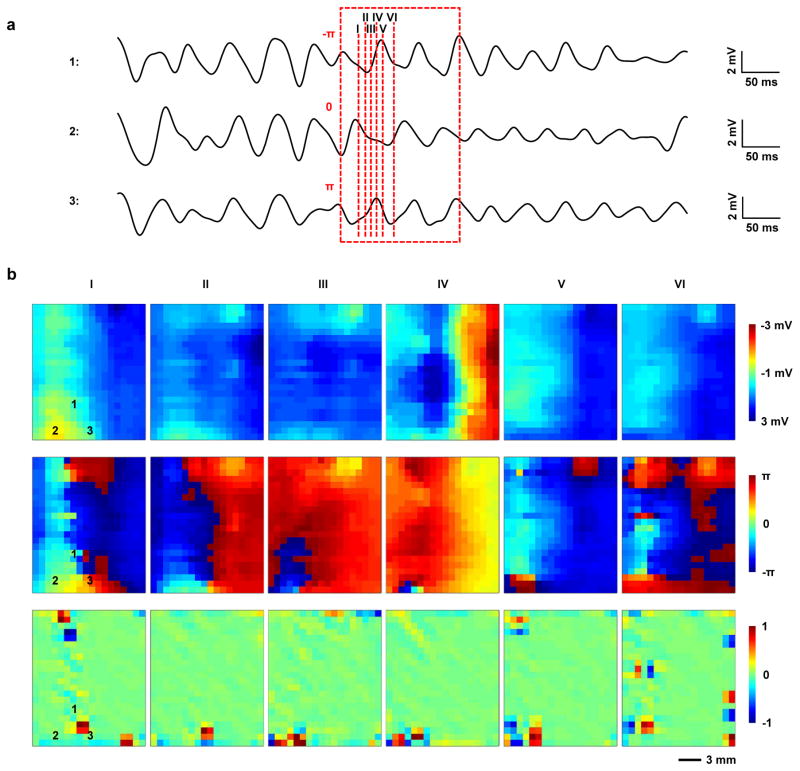

Previously reported flexible passive electrode arrays lacked sufficient spatial density to map and reconstruct patterns of activity associated with VF (ref. 10). The capacitive high-density sensing electronics presented here overcome this limitation, to allow reliable tracking of reentrant patterns of activation (Fig. 5a and 5b, top). Calculation of the signal phase values (Fig. 5b, bottom), a common clinical method for assessing arrhythmias, corroborates these observations. Detecting a singularity in the phase map can identify a reentrant pattern of activation. This singularity is a location around which all values of phase from ππ to π are represented41–43 and can be seen in the first frame of the top two rows of Fig. 5b. In clinical practice, the identification of phase singularities is commonly used to guide ablation therapy of arrhythmias44,45. The location of the phase singularity in each frame (Fig. 5b bottom) can be calculated using the methodology set forth by Bray et al46. The phase singularity is the most positive point on the map that wanders within the bottom right quadrant as the wave of activation passes through a single reentrant pattern. In a single second of recorded data six such reentrant patterns occur, with an average duration of 8.089 ± 2.734 ms. This demonstration has significant implications for use of the electrode in diagnostic catheters and implantable devices aimed at treating patients with life threatening atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.

Figure 5.

Study of ventricular fibrillation (VF). (a) Three representative electronic node signals taken from a heart during VF. The dashed box specifies the window of time corresponding to two reentrant cycles of VF. The labels–π, 0, and +π indicate the initial phase values of the respective signals at the beginning of the reentrant cycle. (b) Voltage, phase and phase singularity maps at six time points corresponding to the dash lines specified in (a). Number 1, 2, and 3 on the maps mark the locations where the signals in (a) were taken. Voltage and phase data indicate a reentrant cycle of VF. A phase singularity commonly refers to a point on a phase map around which all values of phase (i.e. −π to +π) are represented. The phase singularities are identified as the ±1 values associated with regions of the phase map where this occurs. Optical signals from the sensing electronics area also match well with electrical recordings (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Discussion

The results presented here demonstrate a promising route toward safe, robust and high performance flexible electronics for high-density cardiac mapping in both clinical and research settings. Devices with larger area coverages and/or higher density can be readily achieved through scaling the same basic materials and architectures, in a way that leverages advanced processing techniques from the integrated circuit and information display industries. We see no fundamental hurdles, for example, in achieving systems with thousands or even hundreds of thousands of nodes. Autocorrelation methods can be used to identify the node spacing that will maximize acquisition of electrophysiological data while reducing unnecessary redundancy. Future efforts have the potential to yield advanced, stretchable variants of these kinds of systems, to allow coverage across the entire epicardium in a pericardium-like membrane or the entire endocardium by integrating the electronics on balloon catheters. Parallel efforts should also focus on mitigating the foreign body response from these flexible electronic systems. Though minimally invasive, in certain scenarios the devices could potentially induce inflammatory responses that could result in fibrotic tissue and associated impairment of the capacitive measurement interface47–50. The addition of triazole modified hydrogels50 and/or anti-inflammatory agents49 could help to minimize such effects.

While the current work focuses on electrical sensing, energy delivery capabilities could stem from developing high definition capacitively coupled pace-making stimulators. In distinct contrast with optical mapping, the combination of actuators and sensing electrodes both using a capacitively coupled approach has the potential to enable clinically safe systems capable of diagnosing and treating patients with life threatening arrhythmias in real time. In addition, many sudden cardiac deaths occur due to abnormal repolarization caused by mutations in various genes, encoding ion channels governing repolarization. Lack of adequate technology to map repolarization has been a major obstacle in studies of so called long QT syndrome and short QT syndrome, which refer to duration of QT interval of electrocardiogram. The device platforms introduced in our manuscript provide a solution that is key to advancing research, diagnostics and treatment of these lethal cardiac syndromes. Future and on-going work focuses on the engineering development of power supply, data processing units and data transmission interfaces for long-term recording in vivo, achieving systems beyond the realm of what can be envisioned from optical mapping and conventional multielectrode arrays.

Methods

Capacitively coupled active sensing node design

The basic node of the capacitively coupled, active sensing electronics consists of an NMOS source-follower amplifier with a capacitance input and an on-site NMOS multiplexer (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 18). The area of the sensing pad is sufficiently large such that the capacitance between the sensing pad and the tissue is over one order of magnitude higher than the gate capacitance of the sensing transistor. For the 396-ch flexible Si active sensing electronic system in this study, the area of the sensing pad is 270 μm × 460 μm, while the transistor gate area is 13.8 μm × 80 μm. From a thin film capacitor, C = εrε0A/t where εr is the relative permittivity, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, A is the area of the capacitor and t is the thickness of the dielectric, CCAP=12.5CTG. The total capacitance (CT) driving the Si NM channel in the amplifier transistor yields ~ 0.93CTG, from combining CCAP and CTG in series. During sensing, the amplifier transistor operates in saturation (active mode). The transconductance (gm) can be extracted from the standard Square-Law model with the following equation,

| (1) |

where μeff is the effective mobility of electrons in the Si nanomembrane transistor and COX is the specific capacitance of the gate per unit gating area (CT/WLeff). This high capacitance design can ensure high transconductance, which yields high gain and low output impedance from the amplifier.

The source input referred noise (υn,rms, root-mean-squared) of the amplifier circuit can be characterized from the following analytical model28:

| (2) |

where υi(jω) is the input referred amplifier voltage noise (ω = 2πf),ii(jω) is the net current noise at the amplifier input, gCAP + jωCCAP is the tissue-electrode coupling admittance, and gi + jωCi is the amplifier input admittance, and the CS is the active shield to electrode capacitance (Supplementary Fig. 19 depicts the schematic of the active shield circuit). This model clearly shows that high coupling capacitance is beneficial in achieving low-noise circuits. In the low frequency limit, the noise power density can be simplified to ~1/fα, where 0 < α 2. An active shielding circuit further improves the recording gain and the SNR of the sensing. Here, each column input includes an adjustable active shield drive voltage, adjustable column bias current and an adjustable compliance voltage to limit the peak voltage on the column lines. The row select positive and negative voltages are also fully adjustable.

Device fabrication

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 and detailed in Supplementary note 1, the fabrication began with grinding a p-type silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer (200-nm-thick Si layer, 1000-nm-thick Box layer, and 500-μm-thick Si handle wafer, Soitec) to 200 μm (Syagrus Systems). A 200-nm-thick layer of silicon dioxide grown at 1150 °C in a tube furnace served as a diffusion mask. Cleaning the wafer by RCA preceded high-temperature processing, including oxidation and doping. Conventional photolithography defined doping regions, followed by reactive ion etching (RIE) with CF4/O2. The diffusion of phosphorous occurred at 1000 °C in a tube furnace. Photolithography and RIE with SF6 isolated the source, drain, and channel regions of the Si. Tube furnace growth (1150 °C for 37 min) and Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) yielded a gate oxide stack of silicon dioxide (100 nm) and Al2O3 (15 nm). Buffered oxide etchant opened the contact regions for source and drain through photolithographically defined patterns of resist. Electron-beam evaporation yielded a layer of Cr/Au (5 nm/100 nm for the first metal layer; 10 nm/500 nm for the second), patterned by photolithography and wet etching to define the gate electrodes and metal interconnects. An interlayer of polyimide (PI; thickness of 1.6 μm) separated the metal layers. Connections between layers involved through holes defined by lithographically patterned exposure to RIE with O2. Another coating of PI (thickness of 2 μm) isolated the second layer of metal. A layer of Al2O3 (20 nm) coated this top PI surface. Separately, a PI film (Kapton; thickness of 13 μm) laminated on a glass substrate with a thin layer of cured poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) as a soft adhesive served as a handling substrate. Electron-beam evaporation formed a layer of Ti/SiO2 (5 nm/100 nm) on the Kapton film to facilitating bonding with an adhesive (Kwik-Sil, World Precision Instruments) to the devices. Bonding involved placing the device, with PI side facing down, onto the Kapton side, and applying ~50 kPa of pressure. Curing of the adhesive occurred at room temperature within 30 min.

Removal of the Si substrate began with exposure to RIE with SF6, followed by Inductively Coupled Plasma Reactive Ion Etching (STS ICP-RIE). The high selectivity of etching of Si over SiO2 in the ICP-RIE prevented any significant removal of the Box layer during this process. Photolithography then defined areas for forming openings for contact leads via RIE with CF4/O2 and buffered oxide etching. Finally, a laser-cutting procedure defined outer perimeter of the device, thereby allowing it to be peeled from the handling substrate. A Kapton stiffener (~150-μm-thick) reinforced the backside of the contact region, to allow mounting of ZIF (zero-insertion-force) connectors as interfaces to the external data acquisition (DAQ) system.

Analysis of transistor characteristics

The effective mobility (μeff) can be extracted using the following equation,

| (3) |

where VT is the threshold voltage. Subtracting the total phosphorous diffusion length (2xd) from the lithography length (L, 20 μm) yields the effective channel length Leff. The diffusion length can be determined by the thermal history of phosphorus after doping, dominantly the thermal oxidation step for the gate oxide (1150 °C for 37 min). Specifically, xd is calculated from the following analytical model for constant source diffusion,

| (4) |

where D is the diffusivity of phosphorus in Si at 1150 °C (9.1×10−13 cm−2/s), t is time (37 min), NB is the background boron doping in Si (1.3×1015 cm−3), and NS is the solid-solubility limit of phosphorous in Si at 1150 °C (1.5×1021 cm−3). Therefore Leff=L−2xd yields 13.8 μm. Note that depending on whether there is capacitive coupling or not, the values of IDS, COX, and VT will be different. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the extracted effective mobility values as a function of gate overdrive. The peak mobility is ~800 cm2/V.s. During sensing, IDS was set to 1 μA by the current sink. The peak gm is 1.17 mS. The approximate output impedance of the source follower circuit is ~855 Ω, i.e. 1/gm.

Device soak test

Tests involved soaking the active cardiac sensing electrode arrays in a High-density polyethylene (HDPE) plastic tube, filled with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich) solution (pH=7.4). An oven maintained the temperature at 37 °C. Lithium ion batteries biased the device at 3 V relative to a Pt reference electrode inserted into the PBS solution. Detailed experimental settings are in Supplementary Fig. 20. An adhesive (Underwater Magic) sealed the openings in the tube for the device and the electrode to prevent evaporation.

Data acquisition

The electrical data acquisition (DAQ) system consists of a set of five PXI-6289 data acquisition cards (National Instruments) and a custom acquisition system interface board (Supplementary Fig. 21 and 22). The DAQ connects to the multiplexed arrays using flexible High-Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI) cables and an adapter printed circuit board (PCB, Supplementary Fig. 23). The adapter PCB joins to the electrode interface PCB using two 150 μm pitch connectors. The electrode interface PCB adapts from the ZIF connector used on the electrode array to a more durable connector that can be plugged and unplugged without damage (Supplementary Fig. 24). Custom LabVIEW software (National Instruments) controls the DAQ system. All recordings in this study used an over-sampling ratio of 4 to further reduce the noise. The optical mapping involved a sampling frequency of 1 kHz. A triggered TTL pulse aligned the optical signal to electrical data through a direct input of this pulse into the DAQ.

Signal processing

MATLAB software (MathWorks) enabled offline filtering and analysis. Unless otherwise specified, electrical data from all channels passed through a notch filter at 60-Hz and a (1 Hz, 150Hz) band-pass filter. Calculation of the latency of the peak of each channel yielded the minimum latency, for the isochronal maps. Interpolated signals with a 16× enhancement of the sampling mesh allowed accurate location of peaks on a cubic-spline. A final channel mask, also applied based on the amplitude of the peak, eliminating spurious delays.

Mechanical analysis

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) simulations yielded the strain distributions in the device under pure bending by imposing rotations at the two ends of the Kapton layer. The multilayer structure modeling deployed the plane-strain element (CPE4R in the ABAQUS finite element software51. Supplementary Fig. 9 lists the material parameters used for different layers. This simulation neglected the extremely thin Al2O3 layers. The distribution of axial strain along the thickness direction appears in Supplementary Fig. 9, which also shows the distribution of axial strain in the thickness direction. The extremely soft adhesive layer leads to the split of the neutral axes52–54, where the axial strain is zero. This split of neutral axes, above and below the soft adhesive layer, reduces the maximum strain in the device, simply because the maximum strain is proportional to the distance to the neutral axis in each stiff layer. For 5 mm bending radius, the maximum strain is: 0.0243% (tensile) in the top SiO2 layer; 0.0111% (tensile) in top Si layer; 0.0092% (tensile) in the 1st Au layer; 0.0185% (compressive) in the 2nd Au layer.

Animal experiments

The experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the George Washington University in Washington DC. Six adult male New Zealand White rabbits were used over the course of device validation. No randomization or binding was used since there was only a single group. Representative data from the final two experiments are presented here. Briefly, we injected 400 USP (United States Pharmacopeia) units kg-1 of sodium heparin via a lateral ear vein into the rabbit. Afterwards, a progression of 1%-3% isoflurane delivered via facemask anesthetized the rabbit. Once the animal was unconscious and unresponsive to pain, a midsternal incision removed the heart and the aorta cannulated to facilitate retrograde perfusion of oxygenated Tyrode’s solution. The perfusate served a blood substitute for the heart to maintain its electrolyte balance and deliver an energy substrate for continued cardiac function. The solution was at a constant physiologic temperature (37 ± 1 °C) and pH (7.4 ± 0.05) throughout the experiment. The heart was continuously under a constant pressure of 60–80 mm Hg with oxygenated Tyrode’s solution. We administered the excitation-contraction uncoupler Blebbistatin (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) to limit motion artifact in the optical mapping signals. A bolus injection of di-4 ANEPPS (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) facilitated fluorescent measurement of membrane potential (Vm). A plastic band wrapped the active cardiac sensing array and extended around the heart, facilitating mechanical conformity by capillary force from the moisturized heart surface. The data acquisition system connected with PCB board to the array and performed data acquisition. For optical mapping, A 520 nm excitation light elicited optical action potentials and a complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) camera (SciMedia Ltd, Costa Mesa, CA, USA) recorded them with a long pass emission filter with a 650 nm cutoff. Finally, to induce VF in a rabbit model, we administered a 20 nM ATP-dependent potassium channel opener pinacidil (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to shorten action potential duration and create a substrate for induction of VF. Detailed experimental settings can be found in Supplementary Fig. 25. Data was analyzed using a custom MATLAB software that can be downloaded from http://www.efimovlab.org/research/resources.

Data Availability

Source data for the figures in this study are available in figshare with the identifier [https://figshare.com/s/961786fcede5a8703ec5] (ref. 55). The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the NIH grants R01 HL115415, R01 HL114395 and R21 HL112278, and through the Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Center for Microanalysis of Materials at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. We would like to thank the Micro and Nanotechnology Laboratory and the School of Chemical Sciences Machine Shop at the University of Illinois for help on the device fabrication. J.Z. acknowledges supports from Louis J. Larson Fellowship, Swiegert Fellowship and H.C. Ting Fellowship from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. M.J.T. and J.V. acknowledge the support from National Science Foundation award CCF 1422914. C-H.C. and J.V. acknowledge the support from Army Research Office award W911NF-14-1-0173.

Footnotes

Author contributions H.F., K.Y., C.G., Z.Y., I.R.E. and J.A.R. designed the research; H.F., K.Y., Z.Y., C-H.C., J.Z., S.X., S.W., Y.Z., E.S., S.W.H. and D.X. fabricated the devices and electronics; H.F., C.G., Z.Y. and J.Z. carried out animal experiments; H.F., K.Y., C.G., Z.Y., C-H.C., J.Z., M.T., J.V., G.C. and M.K. performed data analysis; H.F., Z.Y., Y.X. and Y.H. contributed to mechanical simulations; H.F., K.Y. C.G., Z.Y., I.R.E. and J.A.R. co-wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Thomas C, Springer P, Loeb G, Berwald-Netter Y, Okun L. A miniature microelectrode array to monitor the bioelectric activity of cultured cells. Experimental cell research. 1972;74:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pertsov AM, Davidenko JM, Salomonsz R, Baxter WT, Jalife J. Spiral waves of excitation underlie reentrant activity in isolated cardiac muscle. Circulation Research. 1993;72:631–650. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sprössler C, Denyer M, Britland S, Knoll W, Offenhäusser A. Electrical recordings from rat cardiac muscle cells using field-effect transistors. Physical review E. 1999;60:2171. doi: 10.1103/physreve.60.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camelliti P, et al. Adult human heart slices are a multicellular system suitable for electrophysiological and pharmacological studies. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2011;51:390–398. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huys R, et al. Single-cell recording and stimulation with a 16k micro-nail electrode array integrated on a 0.18 μm CMOS chip. Lab on a Chip. 2012;12:1274–1280. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Tai J, Park J, Tai Y-C. 2014 IEEE 27th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS); IEEE; pp. 841–844. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman PA. Novel mapping techniques for cardiac electrophysiology. Heart. 2002;87:575–582. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim DH, et al. Materials for multifunctional balloon catheters with capabilities in cardiac electrophysiological mapping and ablation therapy. Nat Mater. 2011;10:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nmat2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DH, et al. Electronic sensor and actuator webs for large-area complex geometry cardiac mapping and therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:19910–19915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205923109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu L, et al. 3D multifunctional integumentary membranes for spatiotemporal cardiac measurements and stimulation across the entire epicardium. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viventi J, et al. A Conformal, Bio-Interfaced Class of Silicon Electronics for Mapping Cardiac Electrophysiology. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viventi J, et al. Flexible, foldable, actively multiplexed, high-density electrode array for mapping brain activity in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1599–U1138. doi: 10.1038/nn.2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laks MM, Arzbaecher R, Bailey JJ, Geselowitz DB, Berson AS. Recommendations for Safe Current Limits for Electrocardiographs A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Committee on Electrocardiography, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996;93:837–839. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.4.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swerdlow CD, et al. Cardiovascular Collapse Caused by Electrocardiographically Silent 60-Hz Intracardiac Leakage Current Implications for Electrical Safety. Circulation. 1999;99:2559–2564. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.19.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beech IB, Sunner J. Biocorrosion: towards understanding interactions between biofilms and metals. Current opinion in Biotechnology. 2004;15:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowman L, Meindl JD. The packaging of implantable integrated sensors. Ieee T Bio-Med Eng. 1986:248–255. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1986.325807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, et al. Stability of the interface between neural tissue and chronically implanted intracortical microelectrodes. IEEE transactions on rehabilitation engineering. 1999;7:315–326. doi: 10.1109/86.788468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazaka K, Jacob MV. Implantable devices: issues and challenges. Electronics. 2012;2:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Someya T, et al. Conformable, flexible, large-area networks of pressure and thermal sensors with organic transistor active matrixes. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12321–12325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502392102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacour SP, Jones J, Wagner S, Li T, Suo Z. Stretchable interconnects for elastic electronic surfaces. P Ieee. 2005;93:1459–1467. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian B, et al. Three-dimensional, flexible nanoscale field-effect transistors as localized bioprobes. Science. 2010;329:830–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1192033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takei K, et al. Nanowire active-matrix circuitry for low-voltage macroscale artificial skin. Nat Mater. 2010;9:821–826. doi: 10.1038/nmat2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz G, et al. Flexible polymer transistors with high pressure sensitivity for application in electronic skin and health monitoring. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1859. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu W, Wen X, Wang ZL. Taxel-addressable matrix of vertical-nanowire piezotronic transistors for active and adaptive tactile imaging. Science. 2013;340:952–957. doi: 10.1126/science.1234855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khodagholy D, et al. NeuroGrid: recording action potentials from the surface of the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:310–315. doi: 10.1038/nn.3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fromherz P, Offenhäusser A, Vetter T, Weis J. A neuron-silicon junction- A Retzius cell of the leech on an insulated- gate field-effect transistor. Science. 1991;252:1290–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.1925540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeck G, Fromherz P. Noninvasive neuroelectronic interfacing with synaptically connected snail neurons immobilized on a semiconductor chip. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:10457–10462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181348698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chi YM, Jung TP, Cauwenberghs G. Dry-contact and noncontact biopotential electrodes: methodological review. IEEE reviews in biomedical engineering. 2010;3:106–119. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2010.2084078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spira ME, Hai A. Multi-electrode array technologies for neuroscience and cardiology. Nature nanotechnology. 2013;8:83–94. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berdondini L, et al. Active pixel sensor array for high spatio-temporal resolution electrophysiological recordings from single cell to large scale neuronal networks. Lab on a Chip. 2009;9:2644–2651. doi: 10.1039/b907394a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eversmann B, et al. A 128× 128 CMOS biosensor array for extracellular recording of neural activity. IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. 2003;38:2306–2317. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakkum DJ, et al. Tracking axonal action potential propagation on a high-density microelectrode array across hundreds of sites. Nat Commun. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byers CL, Beazell JW, Schulman JH, Rostami A. Google Patents. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng FG, Rebscher S, Harrison W, Sun X, Feng H. Cochlear implants: system design, integration, and evaluation. IEEE reviews in biomedical engineering. 2008;1:115–142. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2008.2008250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sillay KA, Larson PS, Starr PA. Deep brain stimulator hardware-related infections: incidence and management in a large series. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:360–367. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000316002.03765.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeong JW, et al. Capacitive Epidermal Electronics for Electrically Safe, Long-Term Electrophysiological Measurements. Advanced healthcare materials. 2014;3:642–648. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan X, et al. Quantification of the affinities and kinetics of protein interactions using silicon nanowire biosensors. Nature nanotechnology. 2012;7:401–407. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fattahi P, Yang G, Kim G, Abidian MR. A review of organic and inorganic biomaterials for neural interfaces. Adv Mater. 2014;26:1846–1885. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langendorff O. Untersuchungen am überlebenden Säugethierherzen. Pflügers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 1895;61:291–332. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Efimov IR, Nikolski VP, Salama G. Optical imaging of the heart. Circulation research. 2004;95:21–33. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000130529.18016.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bossaert L. Fibrillation and defibrillation of the heart. British journal of anaesthesia. 1997;79:203–213. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Efimov IR, Cheng Y, Van Wagoner DR, Mazgalev T, Tchou PJ. Virtual Electrode–Induced Phase Singularity A Basic Mechanism of Defibrillation Failure. Circulation Research. 1998;82:918–925. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.8.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers JM. Combined phase singularity and wavefront analysis for optical maps of ventricular fibrillation. Ieee T Bio-Med Eng. 2004;51:56–65. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.820341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narayan SM, et al. Treatment of atrial fibrillation by the ablation of localized sources: CONFIRM (Conventional Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation With or Without Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation) trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim HS, et al. Noninvasive mapping to guide atrial fibrillation ablation. Cardiac electrophysiology clinics. 2015;7:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ccep.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.BRAY MA, LIN SF, Aliev RR, Roth BJ, Wikswo JP. Experimental and theoretical analysis of phase singularity dynamics in cardiac tissue. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2001;12:716–722. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Onuki Y, Bhardwaj U, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Burgess DJ. A review of the biocompatibility of implantable devices: current challenges to overcome foreign body response. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2008;2:1003–1015. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward WK. A review of the foreign-body response to subcutaneously-implanted devices: the role of macrophages and cytokines in biofouling and fibrosis. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2008;2:768–777. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morais JM, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Burgess DJ. Biomaterials/tissue interactions: possible solutions to overcome foreign body response. The AAPS journal. 2010;12:188–196. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9175-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vegas AJ, et al. Combinatorial hydrogel library enables identification of materials that mitigate the foreign body response in primates. Nat Biotech. 2016;34:345–352. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hibbitt H, Karlsson B, Sorensen P. Abaqus analysis user’s manual version 6.10. Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp; Providence, RI, USA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi Y, Rogers JA, Gao C, Huang Y. Multiple neutral axes in bending of a multiple-layer beam with extremely different elastic properties. Journal of Applied Mechanics. 2014;81:114501. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li L, et al. Integrated flexible chalcogenide glass photonic devices. Nature Photonics. 2014;8:643–649. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su Y, Li S, Li R, Dagdeviren C. Splitting of neutral mechanical plane of conformal, multilayer piezoelectric mechanical energy harvester. Appl Phys Lett. 2015;107:041905. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fang Hui, et al. Dataset for [Capacitively Coupled Arrays of Multiplexed Flexible Silicon Transistors for Long-Term Cardiac Electrophysiology] figshare; 2017. https://figshare.com/s/961786fcede5a8703ec5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data for the figures in this study are available in figshare with the identifier [https://figshare.com/s/961786fcede5a8703ec5] (ref. 55). The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information.