Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of duloxetine monotherapy, in comparison with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) monotherapy, in the treatment of painful physical symptoms (PPS) in Japanese patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) in real-world clinical settings.

Methods

This was a multicenter, 12-week prospective, observational study. This study enrolled MDD patients with at least moderate PPS, defined as a Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) average pain score (item 5) ≥3. Patients were treated with duloxetine or SSRIs (escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, or fluvoxamine) for 12 weeks, and PPS were assessed by BPI-SF average pain score. The primary outcome was early improvement in the BPI-SF average pain score at 4 weeks post-baseline.

Results

A total of 523 patients were evaluated for treatment effectiveness (duloxetine N=273, SSRIs N=250). The difference in BPI-SF average pain score between the two groups was not statistically significant at 4 weeks post-baseline, the primary endpoint (least-squares mean change from baseline [95% confidence interval]: duloxetine, −2.8 [−3.1, −2.6]; SSRIs, −2.5 [−2.8, −2.3]; P=0.166). There was a numerical advantage for duloxetine in improvement from 4 to 12 weeks post-baseline, and the difference was statistically significant at 8 weeks post-baseline (least-squares mean change from baseline [95% confidence interval]: duloxetine, −3.6 [−3.9, −3.3]; SSRIs, −3.1 [−3.4, −2.8]; P=0.023). The 30% and 50% responder rates were significantly higher in patients treated with duloxetine at 4 and 8 weeks post-baseline. There were no serious adverse events experienced by duloxetine-treated patients. The rate of discontinuations due to adverse events was similar for duloxetine and the SSRIs (1.0% and 0.8% of patients, respectively).

Conclusion

In this observational study, BPI-SF improvement was not significantly different at 4 weeks, the primary endpoint; however, patients treated with duloxetine tended to show better improvement in PPS compared to those treated with SSRIs.

Keywords: depression, duloxetine, observational study, pain, SSRI

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a psychiatric disorder that encompasses a broad range of psychological and physical symptoms. Besides typical physical symptoms, such as insomnia or fatigue, painful physical symptoms (PPS) are commonly experienced by patients with MDD. Prevalence of PPS and its clinical importance have been increasingly recognized across Western countries and East Asia, including Japan.1–3

Previous studies have demonstrated that comorbidity of PPS seriously affect the disease state and treatment outcome of MDD. The severity of PPS is closely associated with depression severity at baseline.4 In a study of East Asian patients (excluding Japanese patients) with MDD, the presence of PPS at baseline was associated with greater depression severity, as measured by the Clinical Global Impression-Severity and the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D17) total score.2 In that study, greater improvement in depressive symptoms was observed in patients without PPS at baseline in comparison with those with PPS. The analysis of clinical data from patients with recurrent depression demonstrated that pain severity is a potential marker for treatment-resistant depression.5 Furthermore, based on double-blind clinical trial data of duloxetine versus placebo, there is an association between a decrease in pain and favorable treatment outcomes.6 These results suggest that optimal treatment of PPS may improve the clinical outcome of MDD patients suffering from PPS.

Duloxetine, a potent and selective inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake in vitro and in vivo,7 has been approved for the treatment of MDD and various types of pain (diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and chronic musculoskeletal pain) in the United States as well as in other countries. It has been shown by multiple clinical trials that duloxetine is effective in the treatment of PPS associated with MDD.8–10 Recently, Hong et al11 reported that patients treated with duloxetine had better treatment outcomes compared to those treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In real clinical settings in Japan, however, there are no reports assessing the effectiveness of duloxetine on PPS in comparison with SSRIs. Therefore, the objective of the present 12-week prospective observational study was to assess the effectiveness of duloxetine, in comparison with SSRIs, in the treatment of PPS in Japanese patients with MDD in real clinical settings.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective, observational study, and therefore the health care provider’s decisions regarding the proper treatment and care of the patients were made during the course of normal clinical practice. In addition to duloxetine, the following SSRI therapies were used in the current study: escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine. However, treatment patterns and treatment initiation or changes were solely at the discretion of the physician, but always in accordance with the package insert. There was no attempt to influence the prescribing patterns of any individual investigator. Treatment for MDD was prescribed according to the usual standard of care and was not provided by the study sponsor.

The primary objective of the study, was to assess early improvement in PPS following duloxetine monotherapy in comparison to monotherapy with any SSRI in patients who had at least moderate MDD and at least moderate PPS. The primary endpoint was defined as mean change from baseline in the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) average pain score at 4 weeks post-baseline. Secondary objectives were to assess the effectiveness of duloxetine monotherapy in comparison with SSRI monotherapy on improvement in depression symptoms, quality of life (QoL) measures, social functioning, and treatment outcomes, and to assess the safety profile of duloxetine in a normal clinical setting.

This study was conducted at 39 sites, including psychiatry and psychosomatic outpatient/inpatient clinics/hospitals. The first patient visit occurred on February 13, 2014, and the last patient visit occurred on February 26, 2016. Patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The study was conducted in accordance with good post-marketing study practices (Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare Ordinance No 171 issued on December 20, 2004)12 and applicable laws and regulations, as appropriate. The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare reviewed and approved the protocol.

Patients

Patients were of either gender, with a minimum age of 20 years, who were residents of Japan presenting with an episode of MDD without psychotic traits, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision.13 Patients included in the study were those with at least moderate depression (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report ≥16) and at least moderate PPS (BPI-SF average pain ≥3), as diagnosed by the investigator.

All included patients had not been treated with any antidepressant within 4 weeks prior to study participation, but began antidepressant monotherapy with duloxetine or any SSRI, in accordance with the decision made by the investigator independent from study participation.

Patients were excluded if they had a previous diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder, or had a current diagnosis of dysthymic disorder or adjustment disorder. Patients were also excluded if their PPS originated from organic disease other than MDD or if they were being treated with opioids for their PPS.

Assessments

Patients were observed for 12 weeks after enrollment for a total of five visits: baseline (the start of the study), and 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-baseline. To measure PPS, the BPI-SF (item 5, average pain) was used. Response to treatment was defined as: 1) a ≥30% decrease and 2) a ≥50% decrease on the BPI-SF average pain score from baseline. The following measures were also used: the HAM-D17, rated according to the Structured Interview Guide for the HAM-D17 for depressive symptoms, the EuroQol – 5-Dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D) for QoL, the Social Adaptation Self-Evaluation Scale (SASS), the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) for social functioning, and ability to work (defined as the patient being able to work according to the investigator’s judgment, with the denominator being the entire patient population, excluding patients who retired early, according to data collected at baseline, weeks 4, 8, and 12).

Dose volume (doses at baseline and the average dose during the treatment period) and observed duration were summarized for each drug. For the duloxetine group, the proportion of patients with adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were summarized. AEs were not collected for the SSRI group.

Sample size and statistical methods

Based on the study by Martinez et al,14 a treatment difference of 0.6 for mean change in the BPI-SF average score at 4 weeks was assumed. To ensure 80% statistical power at a 2-sided significance level of 5%, and considering a discontinuation rate of 12%, the sample size was set at 300 patients per arm.

For the safety analysis, all enrolled patients except the following were included: patients with a non-retrievable case report form, patients for whom administration of study drug could not be confirmed, and patients who had no post-baseline visit. For the evaluation of effectiveness, patients in the safety population who did not meet entry criteria and/or had no post-baseline effectiveness data were also excluded. For treatment group comparisons, propensity scoring, the probability of treatment assignment conditioned on observed baseline data, was applied to adjust the potential imbalance of baseline data (eg, preexisting conditions, gender, BPI-SF baseline scores, and ability to work) between treatment groups. Logistic regression was used to compute the propensity score, and generally all available baseline data were included in the model. For the evaluation of continuous and binary data, a mixed effects model with repeated measures analysis was used. The model for fixed effects included treatment (duloxetine/SSRI), propensity score, baseline score (if available), visit, the visit-by-treatment interaction, the visit-by-propensity score interaction, and the visit-by-baseline score interaction (if available).

All statistical tests were based on a 2-sided significance level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.13 or above (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Disposition, discontinuation rate

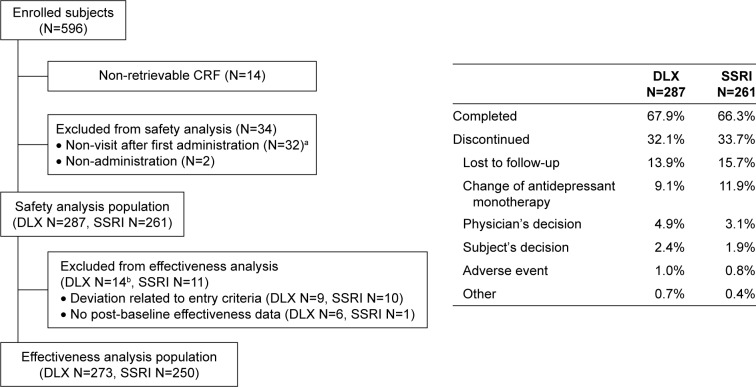

Patient disposition is presented in Figure 1. The safety analysis population consisted of 548 patients (duloxetine N=287, SSRIs N=261). The number of patients evaluated for treatment effectiveness was 523 (duloxetine N=273, SSRIs N=250). Of the 19 subjects who were excluded from the effectiveness analysis for not meeting inclusion criteria, 17 patients did not start the therapy (duloxetine or SSRI) as monotherapy, and two patients were not confirmed as having moderate depression (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (Self-Report) ≥16) and moderate PPS (BPI-SF average pain ≥3). Discontinuation rates were similar for the two treatment groups, and reasons for discontinuation were also similar for the two groups.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

Notes: aNon-visit after first administration, N=32 (DLX =17, SSRI =15). bThe number of DLX patients excluded from the population was 14 instead of 15 because, for one patient, entry criteria were not met and no post-baseline effectiveness data were obtained.

Abbreviations: CRF, case report form; DLX, duloxetine; N, number of patients; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most demographic characteristics were similar for the two treatment groups. However, the proportions of males and females treated with duloxetine and SSRIs were significantly different. Females were more likely than males to be treated with SSRIs in our sample.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics

| DLX N=287 | SSRIs N=261 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 147 (51.2) | 164 (62.8) | 0.007a |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 42.9 (14.6) | 42.6 (15.4) | 0.816b |

| Age (years) at first MDD episode, mean (SD) | 39.2 (13.1) | 39.2 (14.4) | 0.987b |

| Race | 1.000a | ||

| Asian | 286 (99.7) | 261 (100.0) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (0.3) | 0 | |

| Preexisting condition (yes), n (%) | 28 (9.8) | 50 (19.2) | 0.002a |

| Preexisting physical condition which may cause PPS (yes): n (%) | 8 (2.8) | 6 (2.3) | 0.791a |

| Concomitant medications (benzodiazepines): yes, n (%) | 136 (48.2) | 131 (50.2) | 0.668a |

| Concomitant medications (analgesics): yes, n (%)c | 18 (6.3) | 11 (4.2) | 0.341a |

| Concomitant medications (others): yes, n (%) | 141 (49.5) | 128 (49.0) | 0.932a |

| BPI-SF average pain score, mean (SD) | 5.8 (1.7) | 5.4 (1.7) | 0.014b |

| HAM-D17, mean (SD) | 23.8 (6.2) | 23.7 (5.4) | 0.871b |

| EQ-5D, mean (SD) | 0.5055 (0.1504) | 0.5016 (0.1602) | 0.772b |

| GAF, mean (SD) | 49.2 (10.0) | 49.0 (8.1) | 0.791b |

| SASS, mean (SD) | 24.2 (7.2) | 23.2 (6.4) | 0.068b |

| Ability to work or return to work: yes, n (%) | 132 (46.0) | 99 (37.9) | 0.057a |

Notes:

Fisher’s test (exact);

2-sample t-test;

Does not include one patient who used an opioid analgesic.

Abbreviations: BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; DLX, duloxetine; EQ-5D, EuroQol – 5-Dimension questionnaire for quality of life; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HAM-D17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MDD, major depressive disorder; N, number of patients; n, number of affected patients; PPS, painful physical symptoms; SASS, Social Adaptation Self-Evaluation Scale; SD, standard deviation; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Baseline BPI-SF scores were significantly higher in the duloxetine group, compared to the SSRI group (5.8 and 5.4, for duloxetine and SSRIs, respectively; P=0.014). In addition, patients in the SSRI group were more likely to have a preexisting condition, compared to patients in the duloxetine group (9.8% and 19.2% for duloxetine and SSRIs, respectively; P=0.002). The most frequently encountered preexisting conditions (>1%) were hypertension (duloxetine: eight cases; SSRIs: eleven cases) and diabetes mellitus (duloxetine: four cases; SSRIs: five cases).

A summary of dosing is presented in Table 2. The approved doses in Japanese package inserts are shown for each antidepressant, along with the doses prescribed to the patients in this study.

Table 2.

Summary of medication exposure

| DLX (N=287) |

SSRIs

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escitalopram (N=127) |

Sertraline (N=69) |

Paroxetine (N=47) |

Fluvoxamine (N=18) |

All SSRIs (N=261) |

||

| Doses in Japanese package insert, mg/day | ||||||

| Starting dose | 20 | 10 | 25 | 10–20 | 50 | – |

| Approved treatment dose | 40–60 | 10–20 | 25–100 | 20–40 | 50–150 | – |

| Maximum dose | 60 | 20 | 100 | 40 | 150 | – |

| Treatment period (days), mean (SD) | 74.8 (26.1) | 71.4 (25.9) | 76.0 (40.5) | 75.0 (23.6) | 72.2 (25.1) | 73.3 (30.0) |

| Dose (mg/day) at baseline | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 20.6 (2.9) | 8.5 (2.4) | 30.4 (13.5) | 11.7 (4.2) | 47.2 (16.9) | – |

| Median | 20.0 | 10.0 | 25.0 | 10.0 | 50.0 | |

| Average dose (mg/day) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 29.7 (11.7) | 10.0 (3.6) | 47.3 (19.8) | 18.3 (7.0) | 68.1 (30.1) | – |

| Median | 25.2 | 10.0 | 46.3 | 19.1 | 64.8 | – |

Abbreviations: DLX, duloxetine; N, number of patients; SD, standard deviation; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Improvement in PPS

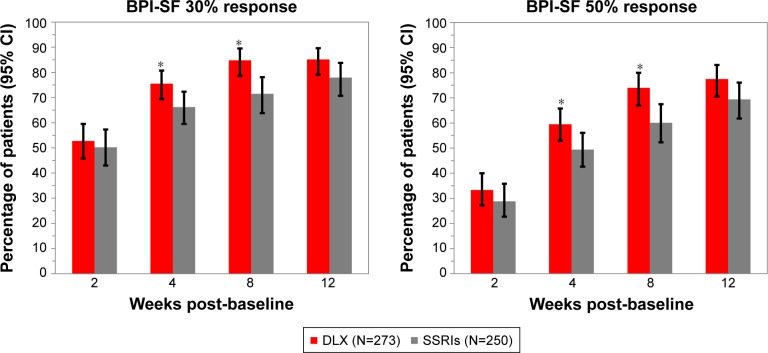

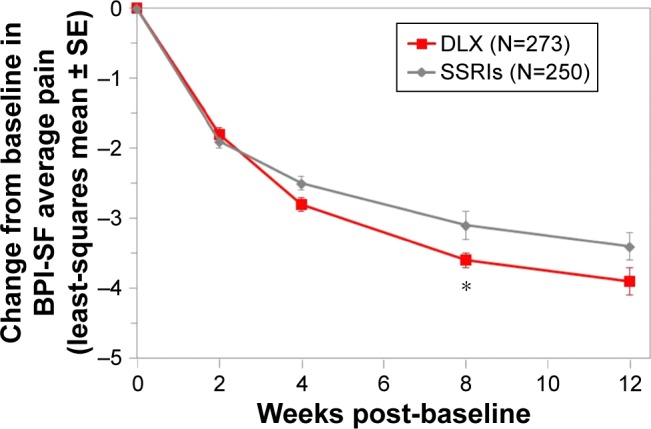

The time course of change from baseline BPI-SF for duloxetine versus the SSRIs is shown in Figure 2. The difference between the two groups on the BPI-SF was not statistically significant at 4 weeks post-baseline, the primary endpoint of this study (duloxetine: least-squares mean [95% confidence interval {CI}] =−2.8 [−3.1, −2.6], SSRI: −2.5 [−2.8, −2.3]; P=0.166). However, there was a numerical advantage for duloxetine in improvement in PPS from 4 weeks to 12 weeks post-baseline. In addition, at 8 weeks post-baseline, this difference was statistically significant (duloxetine: least-squares mean [95% CI], −3.6 [−3.9, −3.3], SSRIs: −3.1 [−3.4, −2.8]; P=0.023), but not at 12 weeks post-baseline (duloxetine: least-squares mean [95% CI] =−3.9 [−4.2, −3.5], SSRIs: −3.4 [−3.7, −3.1]; P=0.062). Regarding response rate, as shown in Figure 3, significantly more duloxetine-treated patients experienced 30% improvement on the BPI-SF than SSRI-treated patients at 4 weeks post-baseline (response rate [95% CI]: duloxetine =75.5% [69.4%, 80.7%]; SSRIs =66.2% [59.5%, 72.3%]; P=0.042) and 8 weeks post-baseline (response rate [95% CI]: duloxetine =84.8% [78.6%, 89.5%]; SSRIs =71.5% [63.8%, 78.1%]; P=0.007). In addition, significantly more duloxetine-treated patients experienced 50% improvement on the BPI-SF than SSRI-treated patients at 4 weeks post-baseline (response rate [95% CI]: duloxetine =59.5% [52.9%, 65.8%]; SSRIs =49.4% [42.6%, 56.1%]; P=0.041) and 8 weeks post-baseline (response rate [95% CI]: duloxetine =74.0% [67.0%, 80.0%]; SSRIs =60.1% [52.3%, 67.5%]; P=0.011).

Figure 2.

Time course of change from baseline in the BPI-SF average pain score for patients treated with DLX and SSRIs (mixed effects model with repeated measures analysis).

Note: *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; DLX, duloxetine; N, number of patients with a baseline measurement; SE, standard error; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Figure 3.

BPI-SF responder (30% and 50%) rates for DLX- and SSRI-treated patients (mixed effects model with repeated measures analysis).

Note: *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; CI, confidence interval; DLX, duloxetine; N, number of patients with a baseline measurement; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

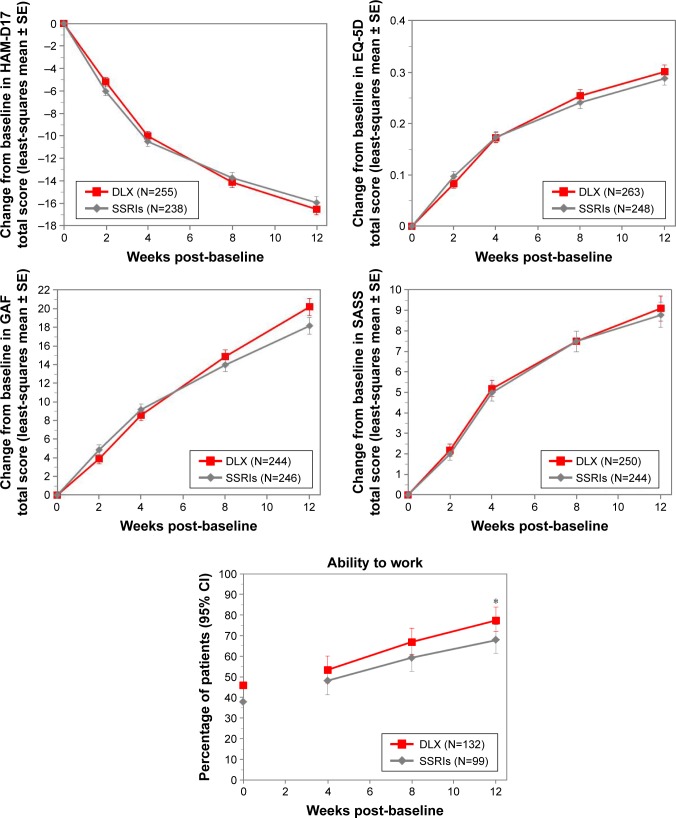

Improvement in depression symptoms, QoL, and functions

No statistically significant differences were noted for the HAM-D17 total score, the EQ-5D, the GAF, or the SASS (Figure 4). However, significantly more duloxetine-treated patients (compared to SSRI-treated patients) were described as having the ability to work at 12 weeks post-baseline (percentage [95% CI]; duloxetine =77.4% [71.0%, 82.8%]; SSRIs =67.9% [60.5%, 74.5%]; P=0.047).

Figure 4.

Change from baseline scores on the HAM-D17, EQ-5D, GAF, SASS, and ability to work for DLX- and SSRI-treated patients (mixed effects model with repeated measures analysis).

Notes: For the ability to work analysis, persons who retired early were excluded. For the ability to work analysis, the baseline scores are the actual values, and not the estimated values calculated via mixed effects model with repeated measures analysis. *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DLX, duloxetine; EQ-5D, EuroQol – 5-Dimension questionnaire for quality of life; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HAM-D17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; N, number of patients with a baseline measurement; SE, standard error; SASS, Social Adaptation Self-Evaluation Scale; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Safety

Discontinuations due to AEs were similar for duloxetine and the SSRIs (1.0% and 0.8% of patients, respectively; Table S1). For patients treated with duloxetine, 8.7% experienced at least one AE (Table S1). AEs occurring in ≥0.5% of patients were somnolence, nausea, decreased appetite, constipation, abdominal discomfort, and malaise. (AEs were not collected for the SSRI treatment group.) There were no SAEs experienced by duloxetine-treated patients.

Discussion

Effectiveness of duloxetine compared to the SSRIs

The present observational study compared the effectiveness of duloxetine and selected SSRIs in the treatment of PPS in patients with MDD in a real-world setting. To our knowledge this is the first study to use this comparison as the primary objective. The primary endpoint of this study, the comparison of mean BPI-SF change from baseline at 4 weeks post-baseline, was not statistically significant. According to Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) recommendations,15 a 2-point or 30% decrease in the numerical rating scale, such as BPI-SF, is associated with patient rating of “much improved”. From 4 weeks to 12 weeks post-baseline, the mean BPI-SF change from baseline at each visit was numerically greater in the duloxetine group, compared to the SSRI group, and this difference was statistically significant at 8 weeks post-baseline. Rates of response to treatment from 4 weeks to 12 weeks post-baseline showed similar trends, with statistically significant differences at 4 weeks and 8 weeks post-baseline. Collectively, these results suggest a beneficial effect of duloxetine on pain associated with MDD in current psychiatric practice in Japan.

Among previous head-to-head studies of duloxetine versus SSRIs, only four studies examined the analgesic effect for PPS in patients with MDD.14,16–18 The primary objectives of each of these studies focused on the antidepressive effects, showing similar effectiveness of duloxetine and SSRIs. As one of the secondary objectives, PPS improvement was examined in these studies using the BPI-SF14 or a visual analog scale (VAS).16–18 Martinez et al,14 reporting the results of an observational study of 750 outpatients in the United States, demonstrated that the mean change of BPI 24-hour average pain from baseline was significantly greater in the duloxetine-treated group compared to the SSRI-treated group at 12 weeks post-baseline. Two studies17,18 compared duloxetine with paroxetine in mostly Asian samples. Lee et al17 showed that, although the numerical advantage for duloxetine in the treatment of overall pain was not statistically significant compared to paroxetine, improvement of back pain was significantly greater in the duloxetine-treated group. The study in Japanese patients18 showed that duloxetine (40 mg/day) had beneficial effects on pain compared to placebo and paroxetine. A randomized study by Goldstein et al16 assessed the effect of duloxetine (40 mg/day and 80 mg/day) and paroxetine for 8 weeks in comparison with placebo using a VAS. Both duloxetine groups (40 mg/day and 80 mg/day) showed numerically greater improvement of overall pain than the paroxetine group, and the higher dose of duloxetine showed significantly greater improvement in shoulder pain than paroxetine (20 mg/day) at 8 weeks post-baseline.

These studies14,16–18 suggest an advantage for duloxetine on PPS compared to SSRIs. But the strength of those findings is limited because they were secondary objectives. In contrast, for the present study, pain reduction was included as a primary endpoint in the MDD population for the first time, and showed a similar advantage of duloxetine compared to the SSRIs for PPS in real-world clinical settings.

The lack of statistical significance at 4 weeks post-baseline in the present study could be due to several reasons. Previously, significant efficacy of duloxetine on PPS in comparison with placebo was demonstrated at 4 weeks post-baseline in three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group studies.8–10 The current study, however, was observational, included an active comparator, and there were substantial differences in multiple aspects of study conditions from those three placebo-controlled clinical trials. For example, naturalistic conditions in treatment choice, drug titration, and patient backgrounds could have affected the effect of duloxetine over treatment course.

In the present study, we recognized that the doses of antidepressants were generally low in real practice in Japan, which was consistent with the previous research.19 This is in agreement with the low AE frequency observed in our study. Particularly, the duloxetine average dose (mean [standard deviation]: 29.7 [11.7] mg/day, median: 25.2 mg/day) was much lower than the lower limit of the approved treatment dose specified in the Japanese package insert, while the SSRI average doses were near or exceeded the lower limit of the approved treatment doses.

In our study, as one of the secondary objectives, we observed that a greater number of patients in the duloxetine-treated group were judged as being able to work, which suggests an advantageous effect of duloxetine on the recovery of social function compared to SSRIs. Even patients with remitted MDD may have difficulties in returning to work.20 Several clinical studies have investigated the impact of antidepressants on the ability to work.21–23 While the restoration of the ability to work by adequate administration of antidepressants has been demonstrated,20,21 cognitive therapy has been shown to be effective in this regard as well.23 Head-to-head studies between antidepressants in different classes have yielded inconsistent results.24,25 Duloxetine has been shown to be effective in improving social function in a placebo-controlled trial.26 As ability to work is important in the recovery from MDD, further investigation into the possible difference among antidepressants may be of interest. Other secondary objectives including HAM-D17 total scores were not significantly different between treatment groups (Figure 4).

Limitations

This was an observational study. Since patients were not randomized to treatments, we cannot draw firm conclusions about cause and effect of outcomes. Even though comparisons between duloxetine and SSRIs were conducted after adjusting the measured confounding factors, potential biases due to unmeasured confounding factors cannot be denied. Treatment options depended solely on physicians’ decisions during the course of normal clinical practice. It is possible that the investigators may have been influenced by their awareness that duloxetine may have an effect on PPS. Our patient sample was mostly Japanese. Potential differences due to gender, ethnicity, or cultural considerations may be underrepresented in this sample. This study was funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and Shionogi Co., Ltd., manufacturers of duloxetine and sponsorship bias may not be completely excluded.

Conclusion

Based on the planned analyses of this observational study conducted in real-world clinical conditions in Japan, early (4 weeks post-baseline) improvement in PPS was not significantly better for duloxetine-treated patients, compared to patients treated with SSRIs. However, patients treated with duloxetine tended to show numerically greater improvement in PPS compared to patients treated with SSRIs. Additionally, the 30% and 50% responder rates were significantly higher in patients treated with duloxetine at 4 and 8 weeks post-baseline compared to patients treated with SSRIs. Collectively, these results suggest a beneficial effect of duloxetine on pain associated with MDD as encountered in current psychiatric practice in Japan.

Supplementary material

Table S1.

Safety profile

| DLX (N=287) n (%) | SSRIs (N=261) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Discontinuations due to AEs | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.8) |

| SAEs | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Subjects with ≥1 AEa | 25 (8.7) | N/A |

| Somnolence | 8 (2.8) | N/A |

| Nausea | 6 (2.1) | N/A |

| Decreased appetite | 3 (1.0) | N/A |

| Constipation | 3 (1.0) | N/A |

| Abdominal discomfort | 2 (0.7) | N/A |

| Malaise | 2 (0.7) | N/A |

Notes:

AEs occurred in ≥0.5% of patients. Detailed information about AEs occurring in SSRI-treated patients was not collected.

Abbreviations: AEs, adverse events; DLX, duloxetine; N, number of patients; n, number of affected patients; N/A, not available; SAEs, serious adverse events; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K., manufacturer/licensee of Cymbalta®, who was involved in the preparation of the manuscript. The study was also funded by Shionogi Co., Ltd. Mr Yasuhiko Hatae and Mr Akira Noguchi (Shionogi Co., Ltd.) managed, and were responsible for this study, including the budget. The study and the analysis were conducted by CMIC Co., Ltd. Medical writing assistance was provided by Rodney Moore, PhD, inVentiv Health Clinical, LLC, funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and Shionogi Co., Ltd.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All of the authors (AK, TT, SH, MM, SF, HT, AY, RE, KT, and TA) contributed to the conception of the study, interpretation of the data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Disclosure

AK, SF, HT, AY, and RE are employees of Eli Lilly Japan K.K. TT, SH, and MM are full-time employees and stockholders of Shionogi & Co., Ltd. KT has no disclosures. TA received speakers’ honoraria from Eli Lilly Japan, K.K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K.

References

- 1.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Eckert GJ, Stang PE, Croghan TW, Kroenke K. Impact of pain on depression treatment response in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(1):17–22. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106883.94059.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ang QQ, Wing YK, He Y, et al. Association between painful physical symptoms and clinical outcomes in East Asian patients with major depressive disorder: a 3-month prospective observational study. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(7):1041–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kishi T, Matsuda Y, Mukai T, et al. A cross-sectional survey to investigate the prevalence of pain in Japanese patients with major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;59:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brnabic A, Lin C, Monkul ES, Dueñas H, Raskin J. Major depressive disorder severity and the frequency of painful physical symptoms: a pooled analysis of observational studies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(12):1891–1897. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.748654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karp JF, Scott J, Houck P, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Pain predicts longer time to remission during treatment of recurrent depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(5):591–597. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fava M, Mallinckrodt CH, Detke MJ, Watkin JG, Wohlreich MM. The effect of duloxetine on painful physical symptoms in depressed patients: do improvements in these symptoms result in higher remission rates? J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):521–530. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bymaster FP, Lee TC, Knadler MP, Detke MJ, Iyengar S. The dual transporter inhibitor duloxetine: a review of its preclinical pharmacology, pharmacokinetic profile, and clinical results in depression. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(12):1475–1493. doi: 10.2174/1381612053764805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaynor PJ, Gopal M, Zheng W, Martinez JM, Robinson MJ, Marangell LB. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in patients with major depressive disorder and associated painful physical symptoms. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(10):1849–1858. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.609539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaynor PJ, Gopal M, Zheng W, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of major depressive disorder and associated painful physical symptoms: a replication study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(10):1859–1867. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.609540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brecht S, Courtecuisse C, Debieuvre C, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine 60 mg once daily in the treatment of pain in patients with major depressive disorder and at least moderate pain of unknown etiology: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1707–1716. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong J, Novick D, Montgomery W, et al. Real-world outcomes in patients with depression treated with duloxetine or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in East Asia. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2016;8(1):51–59. doi: 10.1111/appy.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare . Good Post-marketing Study Practices. 2004. Ordinance No. 171 issued on December 20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez JM, Katon W, Greist JH, et al. A pragmatic 12-week, randomized trial of duloxetine versus generic selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of adult outpatients in a moderate-to-severe depressive episode. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(1):17–26. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32834ce11b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, Wiltse C, Mallinckrodt C, Demitrack MA. Duloxetine in the treatment of depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison with paroxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):389–399. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000132448.65972.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee P, Shu L, Xu X, et al. Once-daily duloxetine 60 mg in the treatment of major depressive disorder: multicenter, double-blind, randomized, paroxetine-controlled, non-inferiority trial in China, Korea, Taiwan and Brazil. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61(3):295–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higuchi T, Murasaki M, Kamijima K. Duloxetine の大うつ病性障害に 対する臨床評価― Placebo 及び paroxetine を対照薬とした二重盲 検比較試験 [Clinical evaluation of duloxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder – placebo-and paroxetine-controlled double-blind comparative study] Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;12:1613–1634. Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furukawa TA, Onishi Y, Hinotsu S, et al. Prescription patterns following first-line new generation antidepressants for depression in Japan: a naturalistic cohort study based on a large claims database. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):916–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romera I, Perez V, Menchón JM, Delgado-Cohen H, Polavieja P, Gilaberte I. Social and occupational functioning impairment in patients in partial versus complete remission of a major depressive disorder episode. A six-month prospective epidemiological study. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(1):58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Erratum. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(4):e1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewa CS, Hoch JS, Lin E, Paterson M, Goering P. Pattern of antidepressant use and duration of depression-related absence from work. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:507–513. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.6.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith EG, Henry AD, Zhang J, Hooven F, Banks SM. Antidepressant adequacy and work status among medicaid enrollees with disabilities: a restriction-based, propensity score-adjusted analysis. Community Ment Health J. 2009;45(5):333–340. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Amsterdam J, Shelton RC, Hollon SD. Gains in employment status following antidepressant medication or cognitive therapy for depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(4):332–338. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.133694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claxton AJ, Chawla AJ, Kennedy S. Absenteeism among employees treated for depression. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(7):605–611. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wade AG, Fernández JL, François C, Hansen K, Danchenko N, Despiegel N. Escitalopram and duloxetine in major depressive disorder: a pharmacoeconomic comparison using UK cost data. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(11):969–981. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826110-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oakes TM, Myers AL, Marangell LB, et al. Assessment of depressive symptoms and functional outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder treated with duloxetine versus placebo: primary outcomes from two trials conducted under the same protocol. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(1):47–56. doi: 10.1002/hup.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Safety profile

| DLX (N=287) n (%) | SSRIs (N=261) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Discontinuations due to AEs | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.8) |

| SAEs | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Subjects with ≥1 AEa | 25 (8.7) | N/A |

| Somnolence | 8 (2.8) | N/A |

| Nausea | 6 (2.1) | N/A |

| Decreased appetite | 3 (1.0) | N/A |

| Constipation | 3 (1.0) | N/A |

| Abdominal discomfort | 2 (0.7) | N/A |

| Malaise | 2 (0.7) | N/A |

Notes:

AEs occurred in ≥0.5% of patients. Detailed information about AEs occurring in SSRI-treated patients was not collected.

Abbreviations: AEs, adverse events; DLX, duloxetine; N, number of patients; n, number of affected patients; N/A, not available; SAEs, serious adverse events; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.