STRUCTURED ABSTRACT

Study Design

Retrospective database study

Objective

The goal of this study was to 1). Evaluate the trends in the use of electromyography (EMG) for instrumented posterolateral lumbar fusions (PLFs) in the United States and 2). Assess the risk of neurological injury following PLFs with and without EMG.

Summary of Background Data

Neurologic injuries from iatrogenic pedicle wall breaches during screw placement are known complications of PLFs. The routine use of intraoperative neuromonitoring (ION) such as EMG during PLF to improve the accuracy and safety of pedicle screw implantation remains controversial.

Methods

A retrospective review was performed using the PearlDiver Database to identify patients that had PLF surgery with and without EMG for lumbar disorders from years 2007 to 2015. Patients undergoing concomitant interbody fusions or spinal deformity surgery were excluded. Demographic trends and risk of neurological injuries were assessed.

Results

During the study period, 2007–2015, 9957 patients underwent PLFs. Overall, EMG was used in 2495 (25.1%) of these patients. There was a steady increase in the use of EMG from 14.9% in 2007 to 28.7% in 2009, followed by a steady decrease to 21.9% in 2015 (p < 0.0001). The risk of postoperative neurological injuries following PLFs was 1.35% (134/9957) with a risk of 1.36% (34/2495) with EMG and 1.34% (100/7462) without EMG (p = 0.932). EMG is used most commonly for PLFs in the Southern part of the United States.

Conclusions

In this retrospective national database review, we found that there was a steady increase in the routine use of EMG for PLFs followed by a steady decline. Regional differences were observed in the utility of EMG for PLFs. The risk of neurological complications following PLF in the absence of spinal deformity is low and the routine use of EMG for PLF may not decrease the risk.

Keywords: intraoperative neuromonitoring, intraoperative monitoring, electrophysiological monitoring, electromyography, EMG, lumbar fusion, posterolateral lumbar fusion, pedicle screw placement, lumbar spine, neurological injury

INTRODUCTION

Instrumentation with pedicle screw constructs is used to achieve stabilization during posterolateral lumbar fusion (PLF) in patients with various lumbosacral spinal disorders. Neurologic injuries from iatrogenic pedicle wall breaches during screw placement are known complications of PLFs with an estimated risk of 0.8% to 6.1%.1–3 To minimize the risk of these complications, intraoperative neuromonitoring (ION) is often used. ION has been used clinically since the 1970s to detect injury to the neural elements.4 Electromyography (EMG), triggered or spontaneous, is a form of ION that monitors peripheral muscle activity from nerve root stimulation from pedicle screw malposition. Spontaneous EMG continuously monitors peripheral nerve roots responsible for muscle innervation using electrodes placed in the muscles corresponding to the level(s) of interest. Spikes, bursts, or trains of activity during surgery may indicate pulling, compression, or stretching of nerves. Triggered EMG helps identify a pedicle wall breach by measuring the amplitude of current intensity required to trigger a nerve root through pedicle screw stimulation, which has been shown to be <10 milliamps (mA) for screw stimulation and 7 mA for probe stimulation.5

While ION has been shown to decrease the risk of neurological injury in spinal deformity surgery, its routine use in PLF remains controversial.6–14 Proponents of the routine use of EMG for PLF claim that it improves both the accuracy and safety of pedicle screw implantation while opponents refute this claim by citing increased cost and no improvement in patient outcomes with EMG use. To date, there is a dearth of literature on how practice patterns vary across the United States with regards to the routine use of EMG for PLFs. The goal of this study was to 1). Evaluate the trends in the use of EMG for instrumented PLFs in the United States and 2). Assess the risk of neurological injury following PLF with and without EMG.

METHODS

A retrospective review was performed using the PearlDiver Patient Record Database (www.pearldiver.com; PearlDiver, Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA) to search through the patient records within the Humana private insurance databases. The PearlDiver database is commercially available and contains de-identified patient data that is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant and allows researchers to construct queries with billing codes to identify patient groupings that meet specified criteria of interest. The raw datasets are filtered by characteristics such as demographic and clinical information. The dataset used in this study spans 2007 through 2015.

Data collection

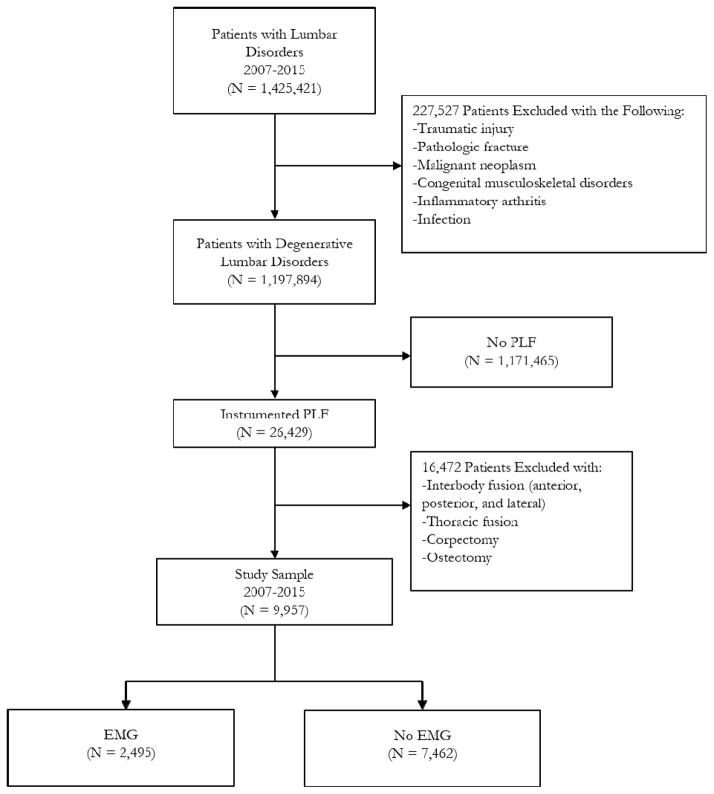

The database was used to identify cases of lumbar disorders undergoing PLFs with and without EMG from years 2007 to 2015 using both current procedural terminology (CPT) and international classification of diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) codes (see Appendix). Patients with potentially confounding diagnoses such as traumatic injuries, pathologic fractures, malignant neoplasms, congenital musculoskeletal disorders, inflammatory arthridities, and infections were excluded (see Appendix).Patients undergoing concomitant interbody fusion (anterior, posterior and lateral), thoracic fusion, corpectomy and osteotomy were also excluded (see Appendix) (Figure 1). The latter three exclusion criteria eliminated spinal deformity surgeries and the interbody exclusion kept the analysis specific to standalone PLFs.

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Statistical analysis

Chi-square hypothesis testing was used. The STATA statistical software version 11.0 (STATACorp, College Station, TX) was used to perform the analyses. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

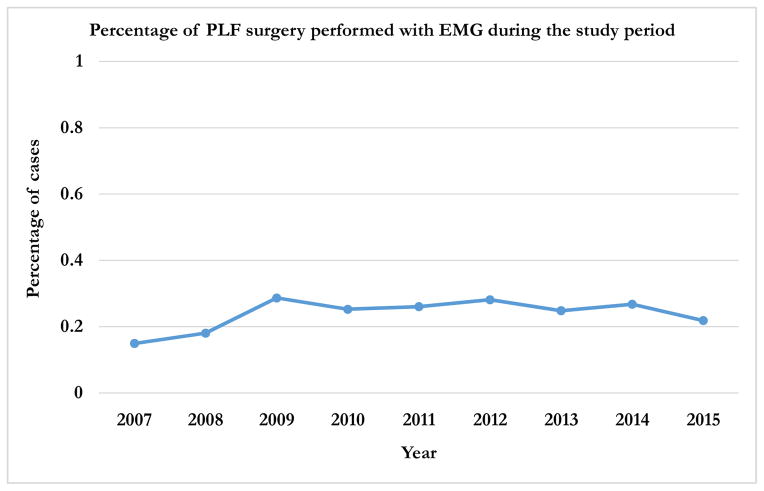

During the study period, 2007–2015, 9957 patients underwent PLF surgery for lumbar disorders. Overall, EMG was used in 2495 (25.1%) of these patients. There was a steady increase in the use of EMG from 14.9% in 2007 to a peak of 28.7% in 2009. This was followed by a steady decrease to 21.9% in 2015 (p < 0.0001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trend in the use of EMG for PLFs during the study period (2007 – 2015)

Age

Among patients that had PLFs, EMG was used in 20.9%, 24.2%, 25.9%, 24.7% and 24.7% of patients in age groups <45, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74 and ≥75 years, respectively (p = 0.418) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information of patients from 2007 to 2015

| Total number of PLFs with EMG | Total number of PLFs | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | p = 0.418 | ||

| < 45 | 66 | 316 | |

| 45 – 54 | 184 | 759 | |

| 55 – 64 | 449 | 1733 | |

| 65 – 74 | 1146 | 4645 | |

| ≥ 75 | 642 | 2604 | |

| Gender | p = 0.21 | ||

| Female | 1409 | 5730 | |

| Male | 1086 | 4227 | |

| Region | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Midwest | 551 | 3210 | |

| Northeast | 72 | 293 | |

| South | 1682 | 5603 | |

| West | 190 | 851 | |

| Total * | 2495 | 9957 |

The discrepancy between total value and summation of values in the age category is attributed to the transfer of patients between subgroups.

Gender

EMG was used in 25.7% of males compared to 24.6% of females that had PLFs (p = 0.21) (Table 1).

Region

The use of EMG for PLFs was most prevalent in the Southern region of the United States (South; 30%, Northeast; 24.6%, West; 22.3% and Midwest; 17.2%, p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

Clinical variables

The most common diagnosis among patients that had PLFs with and without EMGs were lumbar stenosis and spondylolisthesis (Table 2). There was no difference in the mean Charlson co-morbidity index score between the groups (PLFs with EMG: 4.6, PLFs without EMG: 4.1, p = 0.2968) (Table 3). Multi-level fusion surgeries were more common among patients that had PLFs with EMG (80.3% vs. 65.3%, p < 0.0001) (Table 3). The number of revision surgeries in PLFs with and without EMGs was less than 11 in both groups (Table 3).Due to patient privacy limitations of the PearlDiver database, reporting of precise values less than 11 are prohibited.

Table 2.

Diagnosis of patients that had PLFs with and without EMG

| Diagnosis | PLFs with EMG* (n = 2495) | PLFs without EMG* (n = 7462) |

|---|---|---|

| Lumbosacral spondylosis without myelopathy | 824 | 2142 |

| Degeneration of lumbar or lumbosacral intervertebral disc | 978 | 2672 |

| Postlaminectomy syndrome lumbar region | 221 | 453 |

| Other and unspecified disc disorder lumbar region | 102 | 238 |

| Spinal stenosis lumbar region without neurogenic claudication | 2192 | 6261 |

| Spinal stenosis lumbar region with neurogenic claudication | 420 | 1048 |

| Acquired spondylolisthesis | 1253 | 3600 |

| Spondylolysis lumbosacral region | 80 | 148 |

| Spondylolisthesis | 694 | 1694 |

The discrepancy between total value and summation of values in the diagnosis category is attributed to the presence of multiple diagnosis per patient.

Table 3.

Clinical variables of patients that had PLFs with and without EMG

| PLFs with EMG (n = 2495) | PLFs without EMG (n = 7462) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Charlson co- morbidity index (median) | 4.6 (3) | 4.1 (2) | 0.2968 |

| Number of multi-level fusion surgeries (%) | 2004 (80.3%) | 4871 (65.3%) | 0.0001 |

| Number of revision surgeries* (%) | <11 (0 – 0.4%) | <11 (0 – 0.13%) | Not applicable |

Due to patient privacy limitations of the PearlDiver database, reporting of precise values less than 11 are prohibited.

Neurological injury

The overall risk of postoperative neurological injuries within 30 days of the PLF surgery was 1.35% (134/9957). The risk of neurological injury following PLFs with EMG was 1.36% (34/2495) compared to 1.34% (100/7462) in patients without EMG (p = 0.932).

DISCUSSION

Spine surgeons have employed intraoperative neuromonitoring (ION)since the 1970s.4,15 Today, ION is used widely, including in deformity correction, trauma, tumor resection, and scoliosis surgery.6,16 In PLFs, pedicle wall breaches from instrumentation may cause iatrogenic nerve root injury.1–3,17 However, controversy exists on whether or not EMGs should be used routinely in PLFs to decrease the risk of iatrogenic neurological injury from pedicle wall breaches.14 Proponents of EMG claim that it provides useful clinical information regarding the status of the pedicle wall.12,18,19 However, opponents cite evidence of false-negative rates (i.e. post-operative neurologic injury despite normal EMG readings), suggesting that intraoperative EMG does not help surgeons avoid neurologic injury.20,21 Because of this ongoing controversy, the current study aimed to 1).Evaluate the trends in the use of EMG for instrumented PLFs in the United States and 2). Assess the risk of neurological injury following PLFs with and without EMG.

In this retrospective national database review, we found that there was an increase in the use of EMG for PLFs from 2007 to 2009, followed by a steady decrease through 2015. There was no effect of gender or age on national trends of EMG use, however regional differences were noted. The southern region of the United States demonstrated a significantly higher rate of EMG use for PLFs from 2007 – 2015 compared to other regions of the country. Finally, the use of EMG did not decrease the risk of neurological injuries following PLFs.

James et al. published a recent national database study on neuromonitoring in the United States. Contrary to our results, they reported a steady increase in neuromonitoring rates for lumbar procedures from 0.6% to 12.6% from 2007 to 2011, and showed regional differences in neuromonitoring usage.22 However, their inclusion criteria was not selective and included all lumbar procedures (including fusion and non-fusion surgeries), and also included all forms of ION (not just limited to EMG). Additionally, their data included 15% non-elective cases, a subset of patients that were excluded from our dataset.22

Several clinical studies have reported on their experience with EMG for lumbar procedures. Alemoet al. reviewed 86 patients who underwent lumbar or lumbosacral fusion with intraoperative EMG. Five percent of pedicle screws evoked an EMG response resulting in subsequent screw repositioning and no postoperative deficits; however, 3 patients (3.48%) developed a postoperative neurological deficit with a negative intraoperative EMG.20 Parker et al. reviewed 418 patients and 2450 pedicle screws, correlating postoperative CT scan of screw position to intraoperative EMG evoked response. In their series with an incidence of positive intraoperative EMG findings of 4.7%, they found that a threshold of <5mA only had a sensitivity of 43.4% for detecting pedicle wall breaches which calls into question the utility of EMGs to determine pedicle wall breaches.21

Additional clinical studies have reported on the risks of neurologic injury following PLFs which is estimated to range from 0.8% to 6.1%, in line with the rate of 1.35% observed in the current study.1,3,17 In a large national database study that examined neurologic injury rates following lumbar fusion with and without ION, Cole et al. reported rates of 0.32% and 0.58%, respectively, which is lower that the rates of 1.36% and 1.34% observed in the current study.23 However, the study by Cole et al. was not selective and included interbody fusions and all forms of ION (not just limited to EMG). Despite these differences, the authors also concluded that the use of ION did not correlate with reduced intraoperative neurological complications, similar to the findings in the current study.

The lack of a difference in neurologic injuries in this study begs the question: why was there no difference with or without intraoperative EMG? As already discussed, studies have demonstrated a significant false-negative rate from EMG use alone, which would prevent the surgeon from identifying a neurologic injury despite the use of EMG.20,21 Reasons for false-negative rates include anesthesia factors (muscle relaxants or paralytics impair contraction), technical factors (current shunt through pooled blood or soft tissue in screw head, placement of probe on the screw tulip will impair conduction), patient factors (pre-existing nerve damage will have higher triggering thresholds) and implant factors (hydroxyapatite coatings reduce screw conduction capacity).24,25 These factors may each contribute to a surgeon’s inability to identify a nerve injury, and may contribute to the similar risk of neurologic injury with and without EMG found in this study.

Despite risks of false negatives, EMG may be useful to decrease the risk of neurologic injury in subsets of lumbar fusion surgeries. In high-risk deformity surgeries involving vertebral column resections and osteotomies, there is substantial evidence that in the process of deformity correction, ION can assist in early detection of neurologic injuries during traction, compression or ischemia maneuvers.26–29 Additionally, there may be a role for EMG in minimally invasive spine surgeries (MIS), where the neural elements are not visible and in lumbar procedures that involve lateral transpsoas approaches where the lumbosacral nerve plexus is at risk for injury.30–33

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations to this administrative database study. Significant clinical information including disease severity and surgery complexity are not retained in the database and therefore cannot be examined. Specific characteristics of neurologic injury (i.e. transient versus permanent, radiculopathy versus cauda equine injury) are also not maintained in the database and cannot be assessed. In addition, there may be selection bias, as the database draws from private insured patients, and public (Medicare and/or Medicaid) patients may have different characteristics. In addition, it is also possible that surgeons elected to use EMGs for cases perceived to be of higher complexity such as in multi-level and revision surgeries. While revision PLF surgeries have been reported to pose a higher risk for neurological complications due to altered anatomy, we are not aware of any studies that associate multi-level PLF surgery as a risk factor for nerve injury.34 Finally, the interpretation of the information in the PearlDiver database relies on the accuracy of the codes, which is affected by surgeonsand quality of medical coders. Despite these recognized limitations, we believe that this study provides valuable and timely information on clinical practices in the use EMG for PLFs in the United States, where justifying healthcare costs for improved patient outcomes has become a central issue.

CONCLUSION

In this retrospective national database review, we found that there was a steady increase in the routine use of EMG for PLFs in the United States from 2007 – 2009 followed by a steady decrease from 2009 – 2015. Regional differences were observed in the utility of EMG for PLFs in the United States with the South having the highest use. The risk of neurological complications following PLFs is low and the routine use of EMG for PLFs may not decrease the risk. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, we cannot definitively conclude that there is no utility for routine EMG for lumbar pedicle screw placement. However, we believe that future prospective studies will undoubtedly provide valuable information in making an informed choice on the utility of ION for PLFs.

APPENDIX

| Inclusion criteria diagnosis codes for lumbar spine disorders | |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Code |

| Displacement of lumbar intervertebral disc without myelopathy | 722.10 |

| Lumbosacral spondylosis without myelopathy | 721.3 |

| Degeneration of lumbar or lumbosacral intervertebral disc | 722.52 |

| Postlaminectomy syndrome, lumbar region | 722.83 |

| Other and unspecified disc disorder, lumbar region | 722.93 |

| Spinal stenosis, lumbar region, without neurogenic claudication | 724.02 |

| Spinal stenosis, lumbar region, with neurogenic claudication | 724.03 |

| Acquired spondylolisthesis | 738.4 |

| Spondylolysis, lumbosacral | 756.11 |

| Spondylolisthesis | 756.12 |

| Inclusion criteria procedure codes for posterolateral lumbar fusion | |

|---|---|

| Procedure | Code |

| Posterolateral Fusion, Lumbar | 22612 |

| Posterior instrumentation | 22840 |

| Exclusion criteria diagnosis codes |

|---|

| Code Description |

| Congenital Disorders |

| 741.00, 741.01, 741.9, 741.91 |

| 754.2 |

| 756.10, 756.13, 756.14, 756.15, 756.16, 756.17, 756.18, 756.19 |

| Fractures of spinal column |

| 805.00, 805.01, 805.02, 805.03, a805.04, 805.05, 805.06, 805.07, 805.08 |

| 805.10, 805.11, 805.12, 805.13, 805.14, 805.15, 805.16, 805.17, 805.18 |

| Spinal Cord Injuries |

| 806.00, 806.01, 806.02, 806.03, 806.04, 806.05, 806.06, 806.07, 806.08, 806.09 |

| 806.10, 806.11, 806.12, 806.13, 806.14, 806.15, 806.16, 806.17, 806.18, 806.19 |

| 952.00, 952.01, 952.02, 952.03, 952.04, 952.05, 952.06, 952.07, 952.08, 952.09 |

| Pathological fracture |

| 733.1, 733.10, 733.13, 733.95 |

| Vertebral dislocations |

| 839.00, 839.01, 839.02, 839.03, 839.04, 839.05, 839.06, 839.07, 839.08 |

| 839.10, 839.11, 839.12, 839.13, 839.14, 839.15, 839.16, 839.17, 839.18 |

| Abscess or Osteomyelitis |

| 324.1, 324.9 |

| 730.00, 730.01, 730.02, 730.03, 730.04, 730.05, 730.06, 730.07, 730.08, 730.09 |

| 730.10, 730.11, 730.12, 730.13, 730.14, 730.15, 730.16, 730.17, 730.18, 730.19 |

| 730.20, 730.21, 730.22, 730.23, 730.24, 730.25, 730.26, 730.27, 730.28, 730.29 |

| 730.30, 730.31, 730.32, 730.33, 730.34, 730.35, 730.36, 730.37, 730.38, 730.39 |

| 730.70, 730.71, 730.72, 730.73, 730.74, 730.75, 730.76, 730.77, 730.78, 730.79 |

| 730.80, 730.81, 730.82, 730.83, 730.84, 730.85, 730.86, 730.87, 730.88, 730.89 |

| 730.90, 730.91, 730.92, 730.93, 730.94, 730.95, 730.96, 730.97, 730.98, 730.99 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis and other inflammatory spondylopathies |

| 720.0, 720.1, 720.80, 720.81, 720.89, 720.9 |

| Malignant neoplasms |

| 170.2 |

| Exclusion criteria procedure codes | |

|---|---|

| Procedure | Code |

| Anterior Interbody Fusion, Lumbar | 22558 |

| Application of Biomechanical Device (cages, etc). | 22851 |

| Anterior Instrumentation | 22845, 22846, 22847 |

| Posterior Interbody Fusion, Lumbar | 22630 |

| Combined fusion, posterolateral fusion, with posterior interbody fusion | 22633 |

| Thoracic Posterolateral Fusion | 22610 |

| Osteotomy Procedures on the Spine (thoracic and lumbar) | 22212, 22214 |

| Corpectomy (thoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbar) | 63085, 63086, 63087, 63088, 63090, 63091 |

| Inclusion criteria procedure codes for neuromonitoring | |

|---|---|

| Code Description | Code |

| Electromyography | 95860, 95861, 95862, 95863, 95864, 95869, 95870, 95872 |

| Inclusion criteria diagnosis codes for neurologic complications | |

|---|---|

| Code Description | Code |

| Nervous system complications | 997.0 |

| Nervous system complication, unspecified | 997.00 |

| Central nervous system complication | 997.01 |

| Other nervous system complications | 997.09 |

| Injury to lumbar nerve root | 953.2 |

| Injury to sacral nerve root | 953.3 |

Footnotes

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: board membership, consultancy, royalties, stocks.

Level of Evidence: 4

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s). No funds were received in support of this work.

References

- 1.Carreon LY, Puno RM, Dimar JR, 2nd, Glassman SD, Johnson JR. Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2003;85-A(11):2089–2092. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalanithi PS, Patil CG, Boakye M. National complication rates and disposition after posterior lumbar fusion for acquired spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2009;34(18):1963–1969. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ae2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura I, Shingu H, Murata M, Hashiguchi H. Lumbar posterolateral fusion alone or with transpedicular instrumentation in L4--L5 degenerative spondylolisthesis. Journal of spinal disorders. 2001;14(4):301–310. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nash CL, Lorig RA, Jr, Schatzinger LA, Brown RH. Spinal cord monitoring during operative treatment of the spine. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1977;(126):100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calancie B, Madsen P, Lebwohl N. Stimulus-evoked EMG monitoring during transpedicular lumbosacral spine instrumentation. Initial clinical results. Spine. 1994;19(24):2780–2786. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199412150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson EG, Sherman JE, Kanim LE, Nuwer MR. Spinal cord monitoring. Results of the Scoliosis Research Society and the European Spinal Deformity Society survey. Spine. 1991;16(8 Suppl):S361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diab M, Smith AR, Kuklo TR. Neural complications in the surgical treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2007;32(24):2759–2763. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815a5970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggspuehler A, Sutter MA, Grob D, Jeszenszky D, Dvorak J. Multimodal intraoperative monitoring during surgery of spinal deformities in 217 patients. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2007;16(Suppl 2):S188–196. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0427-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbes HJ, Allen PW, Waller CS, et al. Spinal cord monitoring in scoliosis surgery. Experience with 1168 cases. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1991;73(3):487–491. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamerlink JR, Errico T, Xavier S, et al. Major intraoperative neurologic monitoring deficits in consecutive pediatric and adult spinal deformity patients at one institution. Spine. 2010;35(2):240–245. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c7c8f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuwer MR, Emerson RG, Galloway G, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: intraoperative spinal monitoring with somatosensory and transcranial electrical motor evoked potentials*. Journal of clinical neurophysiology : official publication of the American Electroencephalographic Society. 2012;29(1):101–108. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31824a397e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnick DK, Choudhri TF, Dailey AT, et al. Guidelines for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Part 15: electrophysiological monitoring and lumbar fusion. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2005;2(6):725–732. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.6.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhuang Q, Wang S, Zhang J, et al. How to make the best use of intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring? Experience in 1162 consecutive spinal deformity surgical procedures. Spine. 2014;39(24):E1425–1432. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharan A, Groff MW, Dailey AT, et al. Guideline update for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Part 15: electrophysiological monitoring and lumbar fusion. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2014;21(1):102–105. doi: 10.3171/2014.4.SPINE14324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engler GL, Spielholz NJ, Bernhard WN, Danziger F, Merkin H, Wolff T. Somatosensory evoked potentials during Harrington instrumentation for scoliosis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1978;60(4):528–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magit DP, Hilibrand AS, Kirk J, et al. Questionnaire study of neuromonitoring availability and usage for spine surgery. Journal of spinal disorders & techniques. 2007;20(4):282–289. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000211286.98895.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdu WA, Lurie JD, Spratt KF, et al. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: does fusion method influence outcome? Four-year results of the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine. 2009;34(21):2351–2360. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b8a829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunnarsson T, Krassioukov AV, Sarjeant R, Fehlings MG. Real-time continuous intraoperative electromyographic and somatosensory evoked potential recordings in spinal surgery: correlation of clinical and electrophysiologic findings in a prospective, consecutive series of 213 cases. Spine. 2004;29(6):677–684. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000115144.30607.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owen JH, Kostuik JP, Gornet M, et al. The use of mechanically elicited electromyograms to protect nerve roots during surgery for spinal degeneration. Spine. 1994;19(15):1704–1710. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alemo S, Sayadipour A. Role of intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring in lumbosacral spine fusion and instrumentation: a retrospective study. World neurosurgery. 2010;73(1):72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2009.04.024. discussion e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker SL, Amin AG, Farber SH, et al. Ability of electromyographic monitoring to determine the presence of malpositioned pedicle screws in the lumbosacral spine: analysis of 2450 consecutively placed screws. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2011;15(2):130–135. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.SPINE101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James WS, Rughani AI, Dumont TM. A socioeconomic analysis of intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring during spine surgery: national use, regional variation, and patient outcomes. Neurosurgical focus. 2014;37(5):E10. doi: 10.3171/2014.8.FOCUS14449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole T, Veeravagu A, Zhang M, Li A, Ratliff JK. Intraoperative neuromonitoring in single-level spinal procedures: a retrospective propensity score-matched analysis in a national longitudinal database. Spine. 2014;39(23):1950–1959. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland NR. Intraoperative electromyography during thoracolumbar spinal surgery. Spine. 1998;23(17):1915–1922. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199809010-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez AA, Jeyanandarajan D, Hansen C, Zada G, Hsieh PC. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring during spine surgery: a review. Neurosurgical focus. 2009;27(4):E6. doi: 10.3171/2009.8.FOCUS09150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinner DS, Luders H, Lesser RP, Morris HH, Barnett G, Klem G. Intraoperative spinal somatosensory evoked potential monitoring. Journal of neurosurgery. 1986;65(6):807–814. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.65.6.0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bieber E, Tolo V, Uematsu S. Spinal cord monitoring during posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1988;(229):121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones SJ, Edgar MA, Ransford AO, Thomas NP. A system for the electrophysiological monitoring of the spinal cord during operations for scoliosis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1983;65(2):134–139. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B2.6826615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown RH, Nash CL, Jr, Berilla JA, Amaddio MD. Cortical evoked potential monitoring. A system for intraoperative monitoring of spinal cord function. Spine. 1984;9(3):256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bindal RK, Glaze S, Ognoskie M, Tunner V, Malone R, Ghosh S. Surgeon and patient radiation exposure in minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2008;9(6):570–573. doi: 10.3171/SPI.2008.4.08182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wood MJ, Mannion RJ. Improving accuracy and reducing radiation exposure in minimally invasive lumbar interbody fusion. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2010;12(5):533–539. doi: 10.3171/2009.11.SPINE09270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergey DL, Villavicencio AT, Goldstein T, Regan JJ. Endoscopic lateral transpsoas approach to the lumbar spine. Spine. 2004;29(15):1681–1688. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000133643.75795.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodgers WB, Gerber EJ, Patterson J. Intraoperative and early postoperative complications in extreme lateral interbody fusion: an analysis of 600 cases. Spine. 2011;36(1):26–32. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e1040a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eichholz KM, Ryken TC. Complications of revision spinal surgery. Neurosurgical focus. 2003;15(3):E1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.15.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]