Abstract

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies in chronic schizophrenia have found widespread but often inconsistent patterns of white matter abnormalities. These studies have typically used the conventional measure of fractional anisotropy, which can be contaminated by extracellular free-water. A recent free-water imaging study reported reduced free-water corrected fractional anisotropy (FAT) in chronic schizophrenia across several brain regions, but limited changes in the extracellular volume. The present study set out to validate these findings in a substantially larger sample. Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) was performed in 188 healthy controls and 281 chronic schizophrenia patients. Forty-two regions of interest (ROIs), as well as average whole-brain FAT and FW were extracted from free-water corrected diffusion tensor maps. Compared to healthy controls, reduced FAT was found in the chronic schizophrenia group in the anterior limb of the internal capsule bilaterally, the posterior thalamic radiation bilaterally, as well as the genu and body of the corpus callosum. While a significant main effect of group was observed for FW, none of the follow-up contrasts survived correction for multiple comparisons. The observed FAT reductions in the absence of extracellular FW changes, in a large, multi-site sample of chronic schizophrenia patients, validate the pattern of findings reported by a previous, smaller free-water imaging study of a similar sample. The limited number of regions in which FAT was reduced in the schizophrenia group suggests that actual white matter tissue degeneration in chronic schizophrenia, independent of extracellular FW, might be more localized than suggested previously.

Keywords: tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS), neurodegeneration, free-water, Diffusion MRI, ENIGMA

1. Introduction

Diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI) studies in patients with chronic schizophrenia have typically focused on a diffusion index termed fractional anisotropy (FA), which quantifies the directionality of water diffusion (Mori and Zhang, 2006). FA reductions in schizophrenia patients, compared to healthy controls, are typically interpreted as reflecting white matter degeneration. Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) has been the most commonly used approach to study white matter changes across the whole brain. The results of previous studies have been somewhat inconsistent. Whereby some TBSS studies report reduced FA in chronic schizophrenia in several regions across the brain (Asami et al., 2014), specifically the frontal and temporal regions (Scheel et al., 2013), others have failed to find any FA changes associated with schizophrenia (Clark et al., 2012).

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and tractography studies add even further variability to the findings in chronic schizophrenia: VBM studies report reduced FA in the left uncinate fasciculus (Kitis et al., 2011), the bilateral inferior fronto-occiptal fasciculus, the superior longitudinal fasciculus and the genu of the right internal capsule (Nakamura et al., 2012), as well as the left posterior radiata (Cui et al., 2011). Tractography studies report reduced FA in chronic schizophrenia in the arcuate fasciculus (Catani et al., 2011; McCarthy-Jones et al., 2015), the anterior limb of the internal capsule (Rosenberger et al., 2012), the anterior commissure (Choi et al., 2011), the inferior occipito-frontal fasciculus (Oestreich et al., 2015), and the cingulum bundle, uncinate fasciculus and fornix (Kunimatsu et al., 2012). Yet a tractography study by Boos et al. (2013) that investigated a subset of individual white matter tracts did not find any significant FA reductions in chronic schizophrenia patients compared to their healthy siblings or healthy controls. A possible explanation for these inconsistent results across DTI studies is the large variability in data acquisition, processing and analysis protocols (Kubicki et al., 2007).

One of the major limitations of previous DTI studies is the assumption that altered FA equates to structural changes of white matter itself, which can be biased by several factors. Noise in the diffusion-weighted signals refers to the fact that even in a perfectly isotropic medium, the three eigenvalues will never be exactly identical, which introduces a bias into the FA measures (Jones and Cercignani, 2010). The robustness of FA also depends on the number of sampling orientations used and their distribution (Jones and Cercignani, 2010). FA in a given region may further be influenced by factors such as axon diameter, packing density (Takahashi et al., 2002), or membrane permeability (i.e., reduced boundary effectiveness; Jones et al., 2013).

FA measurements are also biased by partial volume with extracellular free-water (Alexander, 2001). Free-water is defined as water molecules that are not restricted or hindered by surrounding tissue and therefore diffuse freely and isotropically in the extracellular space (Pasternak et al., 2009). When different tissue types are captured in one voxel, such as diffusion along white matter tracts and free-water in the extracellular space surrounding those white matter tracts, the DTI indices are no longer tissue-specific but instead represent the weighted average of both compartments. Free-water is predominantly present in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is why CSF contamination is a major problem for fibers in close proximity to the ventricles, such as the cingulum, fornix, and parts of the corpus callosum (Papadakis et al., 2002; Chou et al., 2005; Concha et al., 2005). However, recent studies suggest that varying levels of free-water in the tissue itself, may also account for variability between subjects. In order to remove this confound, Pasternak et al. (2009) developed a technique termed free-water imaging. This enables the differentiation between alterations in the tissue itself as measured by free-water corrected fractional anisotropy (FAT) and extracellular changes as measure by the fractional volume of free-water (FW; Pasternak et al., 2009).

A recent study by Pasternak et al. (2015) used free-water imaging to examine white matter degeneration (measured by FAT) and extracellular volume (measured by FW) in 29 chronic schizophrenia patients compared to healthy controls, and compared these changes to previously documented abnormalities in FAT and FW in first-episode schizophrenia patients (Pasternak et al., 2012). The study revealed that chronic schizophrenia patients exhibited more widespread reductions in FAT relative to the first-episode patients, but more circumscribed increases in FW. Specifically, decreased FAT was observed in the corona radiata bilaterally, splenium and genu of the corpus callosum, bilateral thalamic radiation, bilateral superior longitudinal fasciculus, and the left external capsule. The more widespread reductions in FAT in chronic schizophrenia patients compared with first-episode patients suggested a progressive deterioration of white matter structures in the later stages of schizophrenia, which could indicate a neurodegenerative illness progression of schizophrenia (Pasternak et al., 2015). On the other hand, since the extracellular volume is expected to increase in neuroinflammatory states, the less extensive FW abnormalities found in the chronic patients relative to the first-episode schizophrenia patients suggests that neuroinflammation may play a larger role in the early stages of schizophrenia relative to later, chronic stages of schizophrenia (Pasternak et al., 2012, 2015). The present study aimed to validate the pattern of findings reported by Pasternak et al. (2015) in an independent, substantially larger, and multi-site sample. That is, we predicted to find relatively circumscribed regions of FW abnormalities but more widespread regions of FAT abnormalities in patients with chronic schizophrenia, relative to healthy controls.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

The data for this study was provided by the Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank. The original data collection process is outlined in detail elsewhere (Loughland et al., 2010). In short, patients with schizophrenia were recruited from treatment settings such as hospitals, mental health services, community services and a media campaign. Healthy individuals were also recruited through the media campaign. Clinical assessment officers (CAO), who were either registered or intern psychologists, used a telephone checklist to determine whether individuals were eligible to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria for participants of both groups were an inability to converse fluently in English, intellectual disability as defined as full-scale IQ below 70, movement disorders, electroconvulsive therapy within the past six months and brain injury with more than 24-hours post-traumatic amnesia. CAOs conducted clinical interviews and neuropsychological testing with all eligible participants. The upper limit of antipsychotic drug use duration recorded by the ASRB was 8 years, hence underestimating usage.

Data was analysed for 480 participants, consisting of 193 healthy controls (HC) and 287 individuals who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia according to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Diagnostic and clinical information were collected by trained research staff using the Diagnostic Interview for Psychosis (DIP; Castle et al. 2006; see Table 1 and 2). Five participants were excluded from further analyses due to motion artefacts in the DTI scans and 6 participants were excluded because of a history of a brain disorder. The final sample consisted of 188 healthy control participants and 281 patients with schizophrenia. A subset of the participant sample has been reported on previously in the context of exploring the association between psychotic symptoms and the white matter structural of several tractography-defined white matter fasciculi (McCarthy-Jones et al., 2015; Oestreich et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Demographic data for the participant sample

| Sydney | Perth | Newcastle | Melbourne | Brisbane | Overall difference SZ vs HC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| SZ (n=47) | HC (n=38) | SZ (n=24) | HC (n=27) | SZ (n=14) | HC (n=16) | SZ (n=73) | HC (n=75) | SZ (n=123) | HC (n=32) | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Age: years [M(SD)] | 39.36 (11.14) | 39.29 (14.5 2) | 37.19 (14.15) | 39.38 (10.34) | 45.38 (12.92) | 39.64 (8.25 ) | 38.22 (10.1 2) | 39.41 (13.80) | 38.89 (10.64 ) | 39.03 (13.89) | t(467)=. 57, p=.57 |

| Difference SZ vs HC | t(83)=−.03, p=.98 | t(49)= −.63, p=.53 | t(28)=1.42, p=.17 | t(146)=.60, p=.55 | t(153)=.06, p=.95 | ||||||

| Gender (% male) | 66% | 47 % | 71% | 48 % | 93% | 44 % | 67% | 51 % | 77% | 47% | χ2(2)=29.16, p<.01 |

| Difference SZ vs HC | χ2(1)=2.97, p=.09 | χ2(1)=2.70, p=.10 | χ2(1)=8.10, p<.01 | χ2(1)=4.14, p=.04 | χ2(1)=11.36, p<.01 | ||||||

| Handednessa (%right) | 81% | 71 % | 83% | 52 % | 86% | 69 % | 71% | 80 % | 82% | 56% | χ2(2)=9.65, p=.01 |

| Difference SZ vs HC | χ2(2)=1.79, p=.41 | χ2(2)=6.17, p=.04 | χ2(2)=2.12, p=.35 | χ2(2)=1.80, p=.41 | χ2(2)=28.15, p<.01 | ||||||

Note. SZ = schizophrenia; HC = healthy controls; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

based on three categories: left, right, neither left nor right.

Table 2.

Clinical data for the schizophrenia sample

| Sydney (n=47) | Perth (n=27) | Newcastle (n=16) | Melbourne (n=75) | Brisbane (n=32) | Overall group difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Illness duration [years M(SD)]a | 16.52(9. 75) | 17.24(9. 02) | 17.63(8.48) | 13.83(9. 04) | 15.13(11.00) | F(4,168)=.62, p=.65 |

| Antipsychotics [duration: years M(SD)]b | 5.05(2.78) | 3.86(2.90) | 4.29(3.44 ) | 4.57(2.96) | 3.93(2.97) | F(4,265)=1.54, p=.22 |

| Antipsychotics (type: % atypical)c | 93% | 83% | 85% | 94% | 95% | χ2(4)=5.31, p=.26 |

| Alcohol abused | 29% | 35% | 75% | 33% | 30% | χ2(4)=4.28, p=.37 |

| Drug abusee | 14% | 18% | 13% | 19% | 16% | χ2(4)=1.21, p=.27 |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Hallucinations: M(SD)f | 3.17(4.11) | 4.17(4.80) | 2.29(3.56 ) | 2.79(4.61) | 3.34(4.86) | F(4,280)=.57, p=.69 |

| Depression: M(SD)f | 2.11(3.31) | 2.67(3.42) | 1.93(3.00 ) | 2.26(3.34) | 2.45(3.43) | F(4,280)=.21, p=.94 |

| Thought disorder: M(SD)f | .49(1.38) | .54(1.18 ) | .21(.58) | .33(1.00) | .50(1.21 ) | F(4,280)=.46, p=.77 |

| Delusions: M(SD)f | 1.87(2.93) | 3.00(3.54) | 3.07(3.32 ) | 2.34(3.72) | 2.39(3.29) | F(4,280)=.62, p=.65 |

| Negative symptoms: M(SD)g | 1.68(1.64) | 1.12(1.27) | 2.00(2.45 ) | 1.32(1.05) | .93(1.42 ) | F(4,162)=1.94, p=.10 |

Note.

n=169;

n=266,

n=263,

n=160,

n=158,

n=28,

n=163; symptom scores are based on lifetime ratings form the Diagnostic Interview for Psychoses (DIP).

2.2 Data Acquisition

Diffusion MRI scans were acquired from 1.5T Siemens Avanto scanners from five locations in Australia (McCarthy-Jones et al., 2015). Identical imaging parameters were used across all scanners. Sixty-five axial slices enabling whole-brain coverage in 64 non-collinear gradient directions with a b-value of 1000s/mm2 and one non-diffusion-weighted (b0) image were acquired. Diffusion acquisition had a repetition time (TR) of 8.4s, an echo time (TE) of 88ms, a field of view (FOV) of 25×25cm, a matrix size of 104×104 and 2.5mm slice thickness without gap, producing 2.4mm voxels.

2.3 Processing of diffusion MRI

Intra-scan misalignments due to head movements and eddy currents were removed through affine registration of the diffusion weighted images to the baseline image for each individual participant (FSL, Functional MRI of the Brain [FMRIB] Software Library [FSL]). All images were masked in order to remove non-brain areas and background noise by manually editing a label map, which was initialized using the OTSU module in the software 3D Slicer (www.slicer.org). The FW and FAT maps were generated from the eddy current corrected volumes by fitting the free-water model, following the methods described by Pasternak et al., (2009).

2.4 Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) and Regions of Interest (ROI)

White matter was investigated using whole-brain tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS), according to the protocol provided by the ENIGMA-DTI Working Group (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/ongoing/dti-working-group/). A detailed description of the TBSS procedure is provided by Smith et al. (2006). In brief, FA images from all participants were co-registered into the ENIGMA-DTI template. Each participant’s aligned FA image was then projected onto the ENIGMA-DTI skeleton, which represents a structural core of the white-matter (Jahanshad et al., 2013). This way, a skeletonized FA map was created, such that the central core of each participants’ white matter fiber tracts are represented on the skeleton.

Regions of interest (ROI) were parcellated from the ENIGMA-DTI target, which are defined according to the Johns Hopkins University white matter atlas (Mori et al., 2008; Oishi et al., 2008). In the ENIGMA-DTI protocol, regions which could lead to unreliable estimates because they are often cropped from the field of view (FOV) during image acquisition were removed (Jahanshad et al., 2013). Forty-two ROI, of which 38 were bilateral ROIs (anterior corona radiate; anterior limb of internal capsule; cingulum (cingulate gyrus); cingulum (hippocampus); corona radiata; corticospinal tract; external capsule; fornix/stria terminalis; internal capsule; inferior occipito-frontal fasciculus; posterior corona radiata; posterior limb of the internal capsule; posterior thalamic radiation; retrolenticular part of internal capsule; superior corona radiata; superior fronto-occipital fasciculus; superior longitudinal fasciculus; sagittal stratum; uncinate fasciculus), 4 were interhemispheric ROIs (body of corpus callosum; genu of corpus callosum; splenium of corpus callosum, fornix (column and body)) as well as average FAT and FW were parcellated from the ENGIMA-DTI target. Mean FAT and FW values were extracted for all ROIs.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 22, www.spss.com). A univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) with group (2 levels: HC, SZ) as the between-subjects factor was conducted for the demographic variable age. Chi square tests were performed to test for group differences in gender and handedness.

To investigate FAT and FW of the bilateral tracts, a mixed ANCOVA with group (2 levels: HC, SZ) as the between-subjects factor and tract (19 levels) and hemisphere (left, right) as within-subjects factors were performed for the free-water corrected diffusion metrics FAT and FW. To investigate FAT and FW for interhemispheric tracts (the corpus callosum, which has three pre-established subdivisions, and the fornix), a mixed ANCOVA with group (2 levels: HC, SZ) as the between-subjects factor and tract (4 levels) as within-subjects factor were performed. Scanner location was controlled for in all analyses by adding four dummy variables (for the five scanner locations) as nuisance covariates into all analyses. Gender was also added as nuisance covariate into all analyses due to the significant between-group difference in terms of gender ratio (see Results). In case of a significant main effect of group or a significant group*tract interaction, follow-up contrasts were conducted. The Bonferroni correction was used to control for α-inflation due to multiple comparisons (42 comparisons) such that the critical p-value was set to 0.05/42 = 0.0011.

Pearson correlations were used to investigate correlations between all significant ROIs and age across the entire sample as well as the symptoms hallucinations, delusions, thought disorder and negative symptoms in the patient sample. In order to account for potential effects of antipsychotic medication on white matter structure, DTI measures of ROIs that differed significantly in schizophrenia patients compared to healthy controls were correlated with antipsychotic drug duration.

3. Results

Schizophrenia patients and healthy controls did not differ on age [F(1,467) = .323, p < .570] but differed significantly on gender [χ2(1) = 29.16, p < .001] and handedness [χ2(2) = 9.654, p = .008]. Data on illness duration was available for 160 schizophrenia patients (years: M = 15.10, SD = 9.80). Data on duration of antipsychotic drug use was available for 266 patients (years: M = 4.30, SD = 2.96) and information on typical (n = 19) or atypical (n = 244) antipsychotic drug use was available for 263 schizophrenia patients.

3.1 Free-water corrected Fractional Anisotropy (FAT)

A mixed ANCOVA of the bilateral tracts identified a significant main effect for tract [F(18,8316) = 911.260, p < .001, ηp2 = .664] a significant main effect for hemisphere [F(1,462) = 9.531, p = .002, ηp2 = .020], a significant main effect for group [F(1,462) = 6.516, p = .011, ηp2 = .014] and a significant tract*group interaction [F(18,8316) = 3.858, p < .001, ηp2 = .008]. There was no hemisphere*group interaction [F(1,462) = 1.918, p = .167, ηp2 = .004]. A mixed ANCOVA of the average FAT and the interhemispheric tracts identified a significant main effect for tract [F(4,1848) = 1245.546, p < .001, ηp2 = .729] a significant main effect for group [F(1,462) = 5.325, p = .021, ηp2 = .011], but no tract*group interaction [F(4,1848) = 2.149, p = .139, ηp2 = .005].

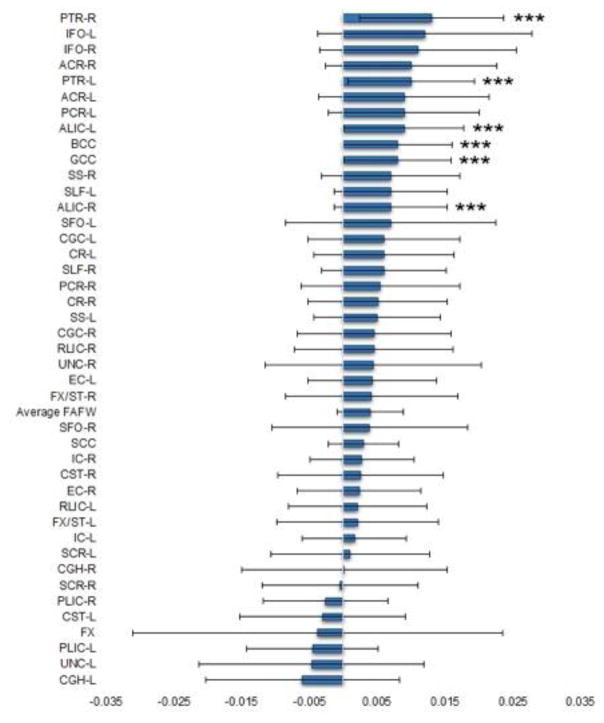

Follow-up contrasts of the bilateral tracts revealed significantly decreased FAT in the SZ group compared to the HC group in the left posterior thalamic radiation [t(467) = 4.203, p < .001, d = .330], the right posterior thalamic radiation [t(467) = 4.807, p < .001, d = .440], the left anterior limb of the internal capsule [t(467) = 4.004, p < .001, d = .212] and the right anterior limb of the internal capsule [t(467) = 3.286, p < .001, d = .294]. Follow-up contrasts of the average FAT and the interhemispheric tracts revealed significantly decreased FAT in the SZ group compared to the HC group in the genu of the corpus callosum [t(467) = 4.097, p < .001, d = .315], and the body of the corpus callosum [t(467) = 4.071, p < .001, d = .338] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean FAT differences between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. ***p < 0.001. PTR-R = Posterior thalamic radiation – right; IFO-L = Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus – left; IFO-R = Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus – right; PTR-L = Posterior thalamic radiation – right; ACR-R = Anterior corona radiata – right; ALIC-L = Anterior limb of internal capsule – left; PCR-L = Posterior corona radiata – left; ACR-L = Anterior corona radiata – left; GCC = Genu of corpus callosum; BCC = Body of corpus callosum; ALIC-R = Anterior limb of internal capsule – right; SLF-L = Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus – left; SS-R = Sagittal stratum (includes ILF and IFO) – right; SFO-L = Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus – left; SLF-R = Superior longitudinal fasciculus – right; CR-L = Corona radiata – left; CGC-L = Cingulum (cingulate gyrus) – left; PCR-R = Posterior corona radiata – right; CR-R = Corona radiata – right; SS-L = Sagittal stratum (includes ILF and IFO) – left; CGC-R = Cingulum (cingulate gyrus) – right; RLIC-R = Retrolenticular part of internal capsule – right; UNC-R = Uncinate fasciculus – right; EC-L = External capsule – left; FX/ST-R = Fornix/Stria terminalis – right; SFO-R = Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus – right; SCC = Splenium of corpus callosum; IC-R = Internal capsule – right; CST-R = Corticospinal tract – right; EC-R = External capsule – right; RLIC-L = Retrolenticular part of internal capsule – left; FX/ST-L = Fornix/Stria terminalis – left; IC-L = Internal capsule – left; SCR-L = Superior corona radiata – left; CGH-R = Cingulum (hippocampus) – right; SCR-R = Superior corona radiata – right; PLIC-R = Posterior limb of internal capsule – left; CST-L = Corticospinal tract –left; FX = Fornix (column and body); PLIC-L = Posterior limb of internal capsule – left; UNC-L = Uncinate fasciculus – left; CGH-L = Cingulum (hippocampus) – left.

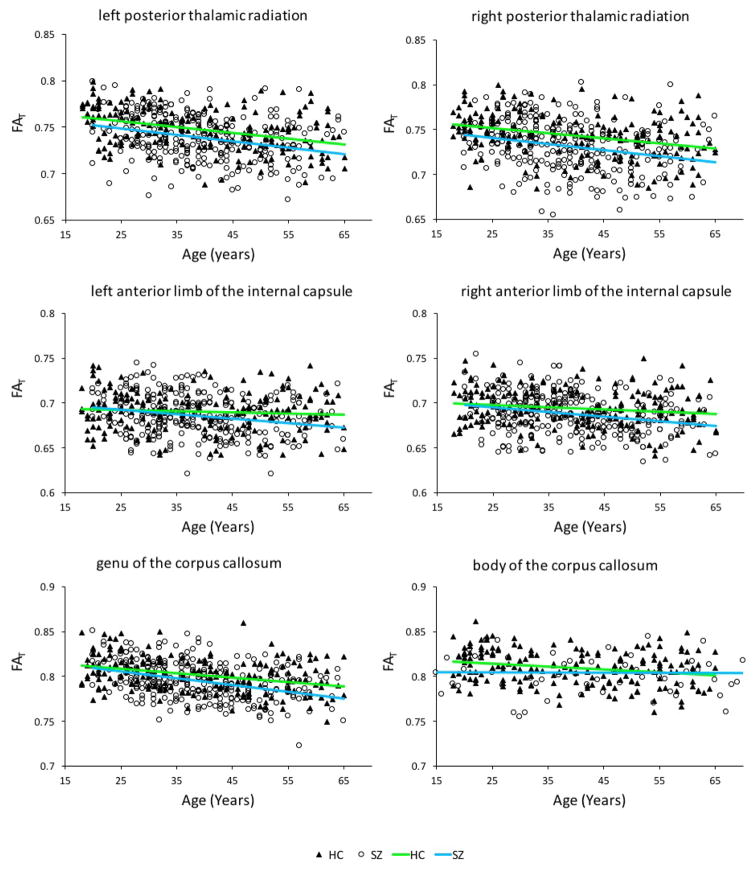

As can be seen in Table 3, FAT correlated significantly with duration of antipsychotic drug use in the right posterior thalamic radiation [r(266) = −.140, p = .022]. There was a significant negative correlation between FAT and age for the healthy controls in the left posterior thalamic radiation [r(188) = −.384, p < .001], the right posterior thalamic radiation [r(188) = −.322, p < .001], the body of the corpus callosum [r(188) = −.234, p = .007], the genu of the corpus callosum [r(188) = −.350, p < .001], but not the left anterior limb of the internal capsule [r(188) = −.074, p = .311] and the right anterior limb of the internal capsule [r(188) = −.157, p = .191]. In the schizophrenia group there was a significant negative correlation between FAT and age for the left posterior thalamic radiation [r(281) = −.290, p < .001], the right posterior thalamic radiation [r(281) = −.248, p < .001], left anterior limb of the internal capsule [r(281) = −.214, p < .001], the right anterior limb of the internal capsule [r(281) = −.248, p < .001], the body of the corpus callosum [r(281) = −.268, p < .001] and the genu of the corpus callosum [r(281) = −.373, p < .001] (see Figure 2). No significant correlations were observed in any of the ROIs between FAT and hallucinations, delusions, thought disorder and negative symptoms (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations of significant FAT tracts with antipsychotic duration and symptoms

| Antipsychotic durationa | Hallucinations | Delusions | Thought Disorder | Negative symptomsb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTR-L | r(266) = −.09, p = .15 | r(281) = −.10, p = .11 | r(281) = −.06, p = .30 | r(281) = −.02, p = .71 | r(163) = .06, p = .47 |

| PTR-R | r(266) = −.14, p = .02* | r(281) = −.10, p = .09 | r(281) < .01, p = .96 | r(281) = .03, p = .65 | r(163) = −.05, p = .52 |

| ALIC-L | r(266) = −.05, p = .46 | r(281) = −.05, p = .41 | r(281) = −.07, p = .28 | r(281) = .07, p = .28 | r(163) = .06, p = .48 |

| ALIC-R | r(266) = −.05, p = .43 | r(281) = −.03, p = .61 | r(281) = −.03, p = .58 | r(281) = .05, p = .41 | r(163) = .09, p = .24 |

| GCC | r(266) = −08, p = .18 | r(281) = −.03, p = .62 | r(281) = −.02, p = .72 | r(281) = −.02, p = .79 | r(163) = −.04, p = .63 |

| BCC | r(266) = −.06, p = .33 | r(281) = −.09, p = .13 | r(281) = −.02, p = .71 | r(281) = −.01, p = .90 | r(163) = −.07, p = .35 |

Note. FAT = free-water corrected fractional anisotropy; PTR-L = left posterior thalamic radiation; PTR-R = right posterior thalamic radiation; ALIC-L = left anterior limb of the internal capsule; ALIC-R = right anterior limb of the internal capsule; GCC = genu of the corpus callosum; BCC = body of the corpus callosum;

p ≤ 0.05;

n=266;

n=163.

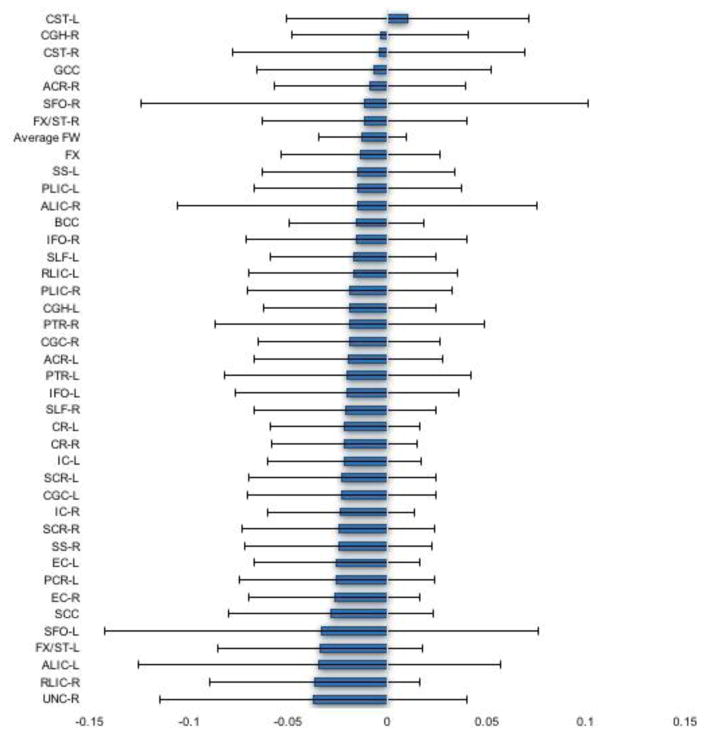

Figure 2.

Mean FW differences between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. UNC-L = Uncinate fasciculus – left; PCR-R = Posterior corona radiata – right; UNC-R = Uncinate fasciculus – right; RLIC-R = Retrolenticular part of internal capsule – right; ALIC-L = Anterior limb of internal capsule – left; FX/ST-L = Fornix/Stria terminalis – left; SFO-L = Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus – left; SCC = Splenium of corpus callosum; EC-R = External capsule – right; PCR-L = Posterior corona radiata – left; EC-L = External capsule – left; SS-R = Sagittal stratum (includes ILF and IFO) – right; SCR-R = Superior corona radiata – right; IC-R = Internal capsule – right; CGC-L = Cingulum (cingulate gyrus) – left; SCR-L = Superior corona radiata – left; IC-L = Internal capsule – left; CR-R = Corona radiata – right; CR-L = Corona radiata – left; SLF-R = Superior longitudinal fasciculus – right; IFO-L = Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus – left; PTR-L = Posterior thalamic radiation – right; ACR-L = Anterior corona radiata – left; CGC-R = Cingulum (cingulate gyrus) – right; PTR-R = Posterior thalamic radiation – right; CGH-L = Cingulum (hippocampus) – left; PLIC-R = Posterior limb of internal capsule – left; RLIC-L = Retrolenticular part of internal capsule – left; SLF-L = Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus – left IFO-R = Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus – right; BCC = Body of corpus callosum; ALIC-R = Anterior limb of internal capsule – right; PLIC-L = Posterior limb of internal capsule – left; SS-L = Sagittal stratum (includes ILF and IFO) – left; FX = Fornix (column and body); FX/ST-R = Fornix/Stria terminalis – right; SFO-R = Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus – right; ACR-R = Anterior corona radiata – right; GCC = Genu of corpus callosum; CST-R = Corticospinal tract – right; CGH-R = Cingulum (hippocampus) – right; CST-L = Corticospinal tract – left.

3.2 Free water (FW)

A mixed ANCOVA of the interhemispheric tracts identified a significant main effect for tract [F(18,8316) = 248.211, p < .001, ηp2 = .349] a significant main effect for hemisphere [F(1,462) = 4.130, p = .043, ηp2 = .009], a significant main effect for group [F(1,462) = 12.113, p = .001, ηp2 = .026], but no significant tract*group [F(18,8316) = .671, p = .630, ηp2 = .001], or hemisphere*group [F(1,462) = .097, p = .756, ηp2 < .001] interaction. A mixed ANCOVA of the average FAT and the interhemispheric tracts identified a significant main effect for tract [F(4,1848) = 195.674, p < .001, ηp2 = .298] a significant main effect for group [F(1,462) = 6.329, p = .012, ηp2 = .014], but no tract*group interaction [F(4,1848) = .656, p = .523, ηp2 = .001].

None of the follow-up contrasts were significant at the Bonferroni corrected alpha level of 0.0011 (see Figure 2).

4. Discussion

This study investigated free-water corrected fractional anisotropy (FAT) and extracellular free-water (FW) in ROIs across the whole brain in a large sample of chronic schizophrenia patients compared to healthy controls. Reduced FAT was observed in the schizophrenia group compared to healthy controls in the posterior thalamic radiation bilaterally, the anterior limb of the internal capsule bilaterally, and both the genu and body of the corpus callosum. While a main effect for group was observed for FW, none of the follow up contrasts survived correction for multiple comparisons with the Bonferroni adjusted alpha level. These findings are in line with the study by Pasternak et al. (2015) which observed reduced FAT in several regions in chronic schizophrenia patients, but found a lesser extent of changes in extracellular volume. The limited number of regions in which reduced FAT findings were observed in the schizophrenia group suggests that actual white matter tissue degeneration in chronic schizophrenia, independent of extracellular volume, might be more localized than suggested by previous studies.

Reduced FA in the anterior limb of the internal capsule is a common finding in schizophrenia and has been linked to lower scores on tests of declarative and episodic memory (Rosenberger et al., 2012; Levitt et al., 2012). FA reductions in the posterior thalamic radiation in schizophrenia patients have also been identified across different image processing analyses (White et al., 2013) and have reportedly been linked to distorted self-perception (Lee et al., 2016). Reduced FA in the corpus callosum of schizophrenia patients are also well documented and have been found to be associated with psychotic symptom severity (Whitford et al., 2010; Knoechel et al., 2012). Moreover, the reduced fiber structure in the corpus callosum of schizophrenia patients highlights the altered interhemispheric connectivity (Whitford et al., 2011), which is broadly consistent with the connectivity hypothesis of schizophrenia (Friston and Frith, 1995).

A recent meta-analysis by the ENIGMA-DTI Working Group of 1,633 chronic schizophrenia patients and 1,398 health controls (Kelly et al., 2016) found significant FA reductions in the schizophrenia group compared to healthy controls in all ROIs that showed significantly reduced FAT in schizophrenia patients in the present study. However, the ENIGMA-DTI meta-analysis reported additional FA reductions in the schizophrenia group across the entire average FA skeleton, fornix, fornix/stria terminalis, sagittal stratum, cingulum, external capsule and uncinate fasciculus. A possible explanation as to why the present study found fewer ROIs with significantly reduced FA in the schizophrenia group than the meta-analysis is the use of free-water corrected DTI measures in the present study. White matter tracts that run in close adjacency to the ventricles like the fornix and cingulum bundle are highly susceptible to CSF contamination (Papadakis et al., 2002; Chou et al., 2005; Concha, et al., 2005). It is therefore possible that the results of previous studies (Kelly et al., 2016; Kunimatsu et al., 2012) which reported reduced FA in the fornix and cingulum bundle, actually reflected changes in extracellular volume as opposed to changes to the white matter microstructure per se.

Our study replicated the findings by Pasternak et al. (2015) which showed that compared to healthy controls, patients with chronic schizophrenia exhibit reduced FAT in the posterior thalamic radiation bilaterally, and in both the genu and body of the corpus callosum. However, as duration of antipsychotic medication use negatively correlated with FAT in the right posterior thalamic radiation, this difference could have been an artefact of antipsychotic use, at least in part. In line with the findings by Pasternak et al. (2015), we observed a negative correlation between age and FAT in both groups in the bilateral posterior thalamic radiation as well as the genu and body of the corpus callosum. Additionally, we also observed that age was negatively correlated with FAT in the left and right anterior limb of the internal capsule in the schizophrenia group only, which might indicate that in these areas, the rate of FAT decrease with age is different in schizophrenia patients than in healthy controls.

We failed to replicate Pasternak et al.’s (2015) finding that FAT was reduced in corona radiata bilaterally, the superior longitudinal fasciculus bilaterally, and the left external capsule, and we found reduced FAT in the anterior limb of the internal capsule bilaterally not detected by this previous study. Additionally, we failed to replicate Pasternak et al.’s (2015) finding of increased FW in schizophrenia patients in the corona radiata and parts of the corpus callosum, as we found no changes in FW in patients compared to controls. Lastly, contrary to Pasternak et al., (2015) we did not find any correlations between FAT and negative symptoms. The fact that the present study did not find any areas with increased FW and fewer areas with reduced FAT than the study by Pasternak et al. (2015) might be explained by our use of the conservative Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Further discrepancies between the study by Pasternak et al., (2015) and the present study might be explained by the fact that whereas we used data collected on five different 1.5T scanners, the study by Pasternak at al. (2015) used data collected on a single 3T scanner. Additionally, the study by Pasternak et al. (2015) used traditional TBSS which involves a voxel-wise comparison. The present study on the other hand used ENIGMA-TBSS, whereby voxels on the white matter skeleton are averaged across regions of interests (ROIs) and estimates are then averaged across the ROIs before group comparisons are conducted. Despite these differences in data acquisition and analysis, the findings by Pasternak et al. (2015) and the findings from the present study both suggest that the primary pathology in the chronic stages of schizophrenia is white matter degeneration as opposed to extracellular pathologies.

Accumulation of free-water is not limited to the ventricles, but can also be found in edema due to ruptures in the blood-brain barrier through processes such as haemorrhage, tumours or brain trauma (Betz et al., 1989; Papadopoulos et al., 2004). Additionally, increased extracellular free-water can also be caused by pathologies such as neuroinflammation, atrophy, low dendritic quantity, low cell density, or a breakdown in the cellular membrane (Selemon et al., 2002; Pasternak et al., 2012; Unterberg et al., 2004). These pathologies, or a combination of them, might account for the mixed and often inconsistent findings of white matter pathologies in schizophrenia (Kubicki et al., 2007; Fitzsimmons et al., 2013). By partialling out free-water before estimating FAT, the present study was able to derive more precise estimations of localized white matter degeneration as opposed to the more general FA measure used in previous studies, which is not able to differentiate between extracellular volume and white matter degeneration.

This study had a number of limitations. First, the data presented in this study were acquired from five scanners. While all scanners were the same model and built according to the same specifications, disparities between the scanners could have potentially impacted the DTI measures. However, it should be noted that scanner location was added as a nuisance covariate to all analysis. Second, while data on duration of antipsychotic drug use were reported, data on antipsychotic dosage was not available, raising the possibility that the observed changes in FAT could, at least in part, be due to antipsychotic medication exposure as opposed to the underlying disease process. Third, by using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons the present study used a relatively strict criterion-for-significance, in order to control for false positive findings. However, the downside of using such a stringent approach is a loss of statistical power. Future studies may wish to use a more hypothesis-driven approach to identify and extract specific tracts-of-interest in order to improve their statistical power. The diffusion MRI data from this study was acquired with a single b-value shell. Multiple b-value shells could increase the accuracy of the bi-tensor model fit (Pasternak et al. 2012). However, the single shell and multiple shells approaches are comparable, particularly when the algorithm to fit the free-water model involves spatial regularization as in the present study (Pasternak et al., 2012). Nevertheless, future studies should consider the acquisition of multiple b-value shells. Finally, we were not able to rule out a number of potential confounds. For example, fewer participants in the schizophrenia group were left-handed and more participants were male compared to the healthy control group. Additionally, there are greater rates of substance use (e.g., smoking, alcohol, illegal drugs) and childhood adversity in patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls (de Leon & Diaz, 2005; Varese et al., 2012), both of which have been linked to white matter changes (Savjani et al., 2014; Hart and Rubia, 2012). Since a large proportion of the schizophrenia patients in this study reported comorbid substance abuse, which is consistent with the documented rates of substance abuse in the general schizophrenia population (Volkow, 2009), we did not exclude these individuals from the analyses. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that, for example, negative health behaviours of people diagnosed with schizophrenia, whether these be coping strategies or attempts at self-medication, may be the cause of the observed changes, rather than an underlying disease process. Further work is needed to address this question.

In conclusion, the present study offered support for the pattern of findings of Pasternak et al. (2015) by finding reduced FAT in multiple regions across the brain, without a simultaneous increase of extracellular volume, in an independent, larger sample of chronic schizophrenia patients. The fact that we observed only a limited number of regions in which FAT was reduced in the schizophrenia group suggests that actual white matter degeneration in chronic schizophrenia, independent of extracellular free-water, might be more localized than reported in previous studies. Future studies might benefit from using free-water corrected measures in order to derive more precise estimations of tissue degeneration independent of extracellular volume.

Figure 3.

Correlations between age and FAT in the ROIs that previously showed significantly reduced FAT in the schizophrenia group. Age was negatively correlated with FAT in the left and right posterior thalamic radiation as well as the genu and the body of the corpus callosum in both groups. Age was negatively correlated with FAT in the left and right anterior limb of the internal capsule in the schizophrenia group but not in the healthy control group.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This study was supported by the Schizophrenia Research Institute using data from the Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank, funded by NHMRC Enabling Grant (No.386500) held by V Carr, U Schall, R Scott, A Jablensky, BMowry, PMichie, S Catts, F Henskens and C Pantelis (Chief Investigators), and the Pratt Foundation, Ramsay Health Care, the Viertel Charitable Foundation, as well the Schizophrenia Research Institute, using an infrastructure grant from the NSW Ministry of Health. Thomas Whitford is supported by a Discovery Project from the Australian Research Council (DP140104394) and a Career Development Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1090507). Part of Simon McCarthy-Jones’ work on this was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE140101077). Ofer Pasternak is supported by the National Institute of Health grants R01MH108574, R01MH085953, R01MH074794, 2P41EB015902, 1R01AG042512, R01MH102377, and a NARSAD young investigator award. Martha Shenton is supported by a VA merit award. Marek Kubicki is supported by a National Institute of Health grant R01 MH102377. Zora Kikinis is supported by a National Institute of Mental Health grant R21MH106793. Peter Savadjiev is supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award, grant number 22591, from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation.

This study was supported by the Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank, which is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Pratt Foundation, Ramsay Health Care, the Viertel Charitable Foundation and the Schizophrenia Research Institute. This work is part of Lena Oestreich’s doctorate thesis (PhD).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributors

Lena Oestreich designed the study, performed the pre-processing of the data and the TBSS analysis, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Dominick Newell, Amanda Lyall, Peter Savadjiev and Sylvain Bouix assisted with the preprocessing of the data and the ENIGMA-TBSS analysis. Zora Kikinis assisted with the design of the study and the interpretation of the results. Thomas Whitford and Simon McCarthy-Jones assisted with the statistical analysis and obtained funding for the study. Ofer Pasternak performed the analysis of the free-water data and assisted with the interpretation of the results. Martha Shenton and Marek Kubicki assisted with the interpretation of the findings. All authors provided assistance with the interpretation of the results and contributed to the writing of the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Field AS. Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4(3):316–329. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: The Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asami T, Hyuk Lee S, Bouix S, Rathi Y, Whitford TJ, Niznikiewicz M, Nestor P, McCarley RW, Shenton ME, Kubicki M. Cerebral white matter abnormalities and their associations with negative but not positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2014;222(1–2):52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz AL, Iannotti F, Hoff JT. Brain edema: a classification based on blood brain barrier integrity. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1989;1(2):133–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos HB, Mandl RC, van Haren NE, Cahn W, van Baal GC, Kahn RS, Hulshoff Pol HE. Tract-based diffusion tensor imaging in patients with schizophrenia and their non-psychotic siblings. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(4):295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle DJ, Jablensky A, McGrath JJ, Carr V, Morgan V, Waterreus A, Valuri G, Stain H, McGuffin P, Farmer A. The diagnostic interview for psychoses (DIP): development, reliability and applications. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):69–80. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani M, Craig MC, Forkel SJ, Kanaan R, Picchioni M, Toulopoulou T, Shergill S, Williams S, Murphy DG, McGuire P. Altered integrity of perisylvian language pathways in schizophrenia: relationship to auditory hallucinations. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(12):1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Kubicki M, Whitford TJ, Alvarado JL, Terry DP, Niznikiewicz M, McCarley RW, Kwon JS, Shenton ME. Diffusion tensor imaging of anterior commissural fibers in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1–3):78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou MC, Lin YR, Huang TY, Wang CY, Chung HW, Juan CJ, Chen CY. FLAIR diffusion-tensor MR tractography: comparison of fiber tracking with conventional imaging. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(3):591–597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K, Narr KL, O’Neill J, Levitt J, Siddarth P, Phillips O, Toga A, Caplan R. White matter integrity, language, and childhood onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(2–3):150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha L, Gross DW, Beaulieu C. Diffusion tensor tractography of the limbic system. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(9):2267–2274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Chen Z, Deng W, Huang X, Li M, Ma X, Huang C, Jiang L, Wang Y, Wang Q, Collier DA, Gong Q, Li T. Assessment of white matter abnormalities in paranoid schizophrenia and bipolar mania patients. Psychiatry Res. 2011;194(3):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon J, Diaz FJ. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(2–3):135–157. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons J, Kubicki M, Shenton ME. Review of functional and anatomical brain connectivity findings in schizophrenia. Curr Opin in Psychiatry. 2013;26(2):172–187. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835d9e6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Frith CD. Schizophrenia: a disconnection syndrome? Clin. Neurosci. 1995;(2):89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart H, Rubia K. Neuroimaging of child abuse: a critical review. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6(52):1–24. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshad N, Kochunov PV, Sprooten E, Mandl RC, Nichols TE, Almasy L, Blangero J, Brouwer RM, Curran JE, de Zubicaray GI, Duggirala R, Fox PT, Hong LE, Landman BA, Martin NG, McMahon KL, Medland SE, Mitchell BD, Olvera RL, Peterson CP, Starr JM, Sussmann JE, Toga AW, Wardlaw JM, Wright MJ, Hulshoff Pol HE, Bastin ME, McIntosh AM, Deary IJ, Thompson PM, Glahn DC. Multi-site genetic analysis of diffusion images and voxelwise heritability analysis: a pilot project of the ENIGMA DTI working group. Neuroimage. 2013;81:455–469. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK, Cercignani M. Twenty-five pitfalls in the analysis of diffusion MRI data. NMR Biomed. 2010;23(7):803–820. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK, Knösche TR, Turner R. White matter integrity, fiber count, and other fallacies: the do’s and don’ts of diffusion MRI. Neuroimage. 2013;73:239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Zhang J. Principles of diffusion tensor imaging and its applications to basic neuroscience research. Neuron. 2006;51(5):527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S, Jahanshad N, Thompson P, Donohoe G ENIGMA Schizophrenia DTI Working Group. ENIGMA-Schizophrenia DTI: Meta-analysis of FA measures in 3,031 cases and controls from 14 countries [abstract]. Organization for Human Brain Mapping Conference; 2016. Poster nr 3528. [Google Scholar]

- Kitiş O, Eker MC, Zengin B, Akyılmaz DA, Yalvaç D, Ozdemir HI, Işman Haznedaroğlu D, Bilgi MM, Gönül AS. The disrupted connection between cerebral hemispheres in schizophrenia patients: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;22(4):213–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knöchel C, Oertel-Knöchel V, Schönmeyer R, Rotarska-Jagiela A, van de Ven V, Prvulovic D, Haenschel C, Uhlhaas P, Pantel J, Hampel H, Linden DE. Interhemispheric hypoconnectivity in schizophrenia: fiber integrity and volume differences of the corpus callosum in patients and unaffected relatives. Neuroimage. 2012;59(2):926–934. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki M, McCarley R, Westin CF, Park HJ, Maier S, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Shenton ME. A review of diffusion tensor imaging studies in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(1–2):15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunimatsu N, Aoki S, Kunimatsu A, Abe O, Yamada H, Masutani Y, Kasai K, Yamasue H, Ohtomo K. Tract-specific analysis of white matter integrity disruption in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;201(2):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Kim B, Oh D, Kim MK, Kim KH, Bang SY, Choi TK, Lee SH. White matter alterations associated with suicide in patients with schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2016;248:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt JJ, Alvarado JL, Nestor PG, Rosow L, Pelavin PE, McCarley RW, Kubicki M, Shenton ME. Fractional anisotropy and radial diffusivity: diffusion measures of white matter abnormalities in the anterior limb of the internal capsule in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;136(1–3):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughland C, Draganic D, McCabe K, Richards J, Nasir A, Allen J, Catts S, Jablensky A, Henskens F, Michie P, Mowry B, Pantelis C, Schall U, Scott R, Tooney P, Carr V. Australian schizophrenia research bank: a database of comprehensive clinical, endophenotypic and genetic data for aetiological studies of schizophrenia. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2010;44(11):1029–1035. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.501758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy-Jones S, Oestreich LKL, Whitford TJ Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank. Reduced integrity of the left arcuate fasciculus is specifically associated with hallucinations in the auditory verbal modality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;162(1–3):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Oishi K, Jiang H, Jiang L, Li X, Akhter K, Hua K, Faria AV, Mahmood A, Woods R, Toga AW, Pike GB, Neto PR, Evans A, Zhang J, Huang H, Miller MI, van Zijl P, Mazziotta J. Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an ICBM template. Neuroimage. 2008;40(2):570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kawasaki Y, Takahashi T, Furuichi A, Noguchi K, Seto H, Suzuki M. Reduced white matter fractional anisotropy and clinical symptoms in schizophrenia: a voxel-based diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 2012;202(3):233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oestreich LKL, McCarthy-Jones S, Whitford TJ Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank. Decreased integrity of the fronto-temporal fibers of the left inferior occipito-frontal fasciculus associated with auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia. Brain Imaging and Behav. 2015;10(2):445–454. doi: 10.1007/s11682-015-9421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K, Zilles K, Amunts K, Faria A, Jiang H, Li X, Akhter K, Hua K, Woods R, Toga AW, Pike GB, Rosa-Neto P, Evans A, Zhang J, Huang H, Miller MI, van Zijl PC, Mazziotta J, Mori S. Human brain white matter atlas: identification and assignment of common anatomical structures in superficial white matter. Neuroimage. 2008;43(3):447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis NG, Martin KM, Mustafa MH, Wilkinson ID, Griffiths PD, Huang CL, Woodruff PW. Study of the effect of CSF suppression on white matter diffusion anisotropy mapping of healthy human brain. Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;48(2):394–398. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S, Binder DK, Manley GT, Krishna S, Verkman AS. Molecular mechanisms of brain tumor edema. Neuroscience. 2004;129(4):1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Sochen N, Gur Y, Intrator N, Assaf Y. Free water elimination and mapping from diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(3):717–730. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Westin CF, Bouix S, Seidman LJ, Goldstein JM, Woo TU, Petryshen TL, Mesholam-Gately RI, McCarley RW, Kikinis R, Shenton ME, Kubicki M. Excessive extracellular volume reveals a neurodegenerative pattern in schizophrenia onset. J Neurosci. 2012;32(48):17365–17372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2904-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Shenton ME, Westin CF. Estimation of extracellular volume from regularized multi-shell diffusion MRI. MICCAI. 2012;15(2):305–312. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-33418-4_38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Westin CF, Dahlben B, Bouix S, Kubicki M. The extent of diffusion MRI markers of neuroinflammation and white matter deterioration in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger G, Nestor PG, Oh JS, Levitt JJ, Kindleman G, Bouix S, Fitzsimmons J, Niznikiewicz M, Westin CF, Kikinis R, McCarley RW, Shenton ME, Kubicki M. Anterior limb of the internal capsule in schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor tractography study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2012;6(3):417–425. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savjani RR, Velasquez KM, Thompson-Lake DG, Baldwin PR, Eagleman DM, De La Garza R, Salas R. Characterizing white matter changes in cigarette smokers via diffusion tensor imaging. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel M, Prokscha T, Bayerl M, Gallinat J, Montag C. Myelination deficits in schizophrenia: evidence from diffusion tensor imaging. Brain Struct Funct. 2013;218(1):151–156. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selemon LD, Kleinman JE, Herman MM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Smaller frontal gray matter volume in postmortem schizophrenic brains. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(12):1983–1991. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, Watkins KE, Ciccarelli O, Cader MZ, Matthews PM, Behrens TE. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31(4):1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Hackney DB, Zhang G, Wehrli SL, Wright AC, O’Brien WT, Uematsu H, Wehrli FW, Selzer ME. Magnetic resonance microimaging of intraaxonal water diffusion in live excised lamprey spinal cord. PNAS. 2002;99(25):16192–16196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252249999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterberg AW, Stover J, Kress B, Kiening KL. Edema and brain trauma. Neuroscience. 2004;129(4):1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, Lieverse R, Lataster T, Viechtbauer W, Read J, van Os J, Bentall RP. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;8(4):661–671. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND. Substance use disorders in schizophrenia--clinical implications of comorbidity. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(3):469–472. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T, Ehrlich S, Ho BC, Manoach DS, Caprihan A, Schulz SC, Andreasen NC, Gollub RL, Calhoun VD, Magnotta VA. Spatial characteristics of white matter abnormalities in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(5):1077–1186. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford TJ, Kubicki M, Schneiderman JS, O’Donnell LJ, King R, Alvarado JL, Khan U, Markant D, Nestor PG, Niznikiewicz M, McCarley RW, Westin CF, Shenton ME. Corpus callosum abnormalities and their association with psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(1):70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford TJ, Kubicki M, Ghorashi S, Schneiderman JS, Hawley KJ, McCarley RW, Shenton ME, Spencer KM. Predicting inter-hemispheric transfer time from the diffusion properties of the corpus callosum in healthy individuals and schizophrenia patients: a combined ERP and DTI study. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2318–2329. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]