Summary

In genetic case-control association studies, a standard practice is to perform the Cochran-Armitage (CA) trend test with 1 degree-of-freedom (df) under the assumption of an additive model. However, when the true genetic model is recessive or near recessive, it is outperformed by Pearson’s χ2 test with 2 df. In this paper we analytically reveal the statistical basis that leads to the phenomenon. First, we show that the CA trend test examines the location shift between the case and control groups, whereas Pearson’s χ2 test examines both the location and dispersion shifts between the two groups. Second, we show that under the additive model the effect of location deviation outweighs that of the dispersion deviation, and vice versa under a near recessive model. Therefore Pearson’s χ2 test is a more robust test than the CA trend test and it outperforms the latter when the mode of inheritance evolves to the recessive end.

Keywords: trend test, Pearson’s chi-squared test, location, dispersion

In genetic association studies, in particular for genome-wide screens, the Cochran-Armitage (CA) trend test (Cochran, 1954; Armitage, 1955) under the assumption of an additive genetic model became the standard practice following Sasieni’s seminal paper (Sasieni, 1997). However, this approach suffers power loss when the true genetic model is non-additive. In contrast, Pearson’s χ2 test (Pearson, 1900) with 2 degree-of-freedom (df), which is an omnibus test without regard to genetic models, is robust to any underlying models. It outperforms the CA trend test when the mode of inheritance is recessive or near recessive, which was shown by numeric simulation studies (e.g., Gonzalez et al., 2008; Kuo & Feingold, 2010; Li et al., 2009; Loley et al., 2013). A convenient explanation of the phenomenon is that the incorrect model assumption results in significant power loss, which is true yet futile. Here we aim to elucidate the underlying statistical cause that leads to the different performance of the two tests.

Consider a diallelic locus with the major and minor alleles denoted as α and A, respectively, in a case-control study (Table 1). Denote by ri and si the numbers of cases and controls, respectively, in genotype category Gi, where i ∈ {0,1,2} reflects the number of A alleles a subject has. Thus G0, G1, and G2 correspond to genotypes aa, Aa, and AA, respectively. Denote by R, S, and ni the marginal sums such that , and ni = ri + si, and denote by N the total sample size such that . Assume (r0, r1, r2) follow a trinomial distribution with parameters R and (p0, p1, p2), and (s0, s1, s2) follow a trinomial distribution with parameters S and (q0, q1, q2). The null hypothesis of no association between the disease and genotype is H0: pi = qi.

Table 1.

Genotype distribution at a diallelic marker in a case-control study

| Phenotype | Genotype | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aa | Aa | AA | ||

| Cases | r0 | r1 | r2 | R |

| Controls | s0 | s1 | s2 | S |

| Total | n0 | n1 | n2 | N |

Assign a set of scores (x0, x1, x2) to the three genotypes aa, aA and AA, respectively, with the constraints x0 ≤ x1 ≤ x2 and x0 < x2. The CA trend test statistic is . Under the null hypothesis, TCA follows a χ2 distribution with 1 df.

The CA trend test statistic is identical to that of a test for the difference of the average scores between the cases and controls. The derivation details are described in Appendix I, and here we summarize the results. Denote by Xj the score of the j-th subject (j = 1, …, R) in the case group and by Yk the score of the k-th subject (k = 1, …, S) in the control group. Then and are the mean scores of the two groups. To test for the difference between the score means, a statistic can be defined as , where is the estimated variance of (X̄ – Ȳ) under the null hypothesis. Tmean also follows a χ2 distribution with 1 df. The numerator . The denominator . By some algebraic manipulations, it can be shown that Tmean = TCA. Therefore the CA trend test is equivalent to a two-sample mean test for the difference of the average scores. In other words, the CA trend test examines the location shift of cell counts between cases and controls.

Pearson’s χ2 test is an omnibus test for independence in a contingency table. Unlike the CA trend test, it does not require assignment of a score xi to each genotype category to reflect assumptions about the genetic model. The test statistic is . Under the null hypothesis, TP follows a χ2 distribution with 2 df.

Here we show how TP can be partitioned into components that measure the location effect and components that measure the dispersion effect by orthogonal polynomials (Rayner & Best, 2000; Beh, 2001). Define a set of orthogonal polynomials g0(xi) = 1, , and , where , where j ∈ {2,3,4} and . Define and , where u ∈ {1,2}. Note that μ is the mean score of the overall table; V11 and V12 are functions of the location shift of scores in cases and controls, respectively; V21 and V22 are functions of the dispersion of scores in cases and controls, respectively. It can be shown that (see Appendix II for details). Therefore, Pearson’s χ2 test statistic can be decomposed into two parts, with measuring the location deviation and measuring dispersion deviation between cases and controls. In other words, Pearson’s χ2 test simultaneously examines the location and dispersion shifts of cell counts between cases and controls.

Above we analytically show that the difference between the CA trend test and Pearson’s χ2 test is that the former only examines the location shift, whereas the latter examines both the location and dispersion shifts between the case and control groups. Below we show by simulation how this difference leads to distinct performance of the two tests under varying genetic models.

To connect the genetic and statistical models, here we parameterize the model using some genetic jargon. Set the genotype group G0, i.e., aa, as the reference group. Define penetrance as fi = P(Affected|Gi), and genotype relative risk as λi = fi/f0. Therefore λ0 = 1. The null hypothesis of no association can be expressed as H0: λ1 = λ2 = 1. Under the alternative hypothesis, λ2 ≥ λ1 ≥ 1 and λ2 > 1. A genetic model can be described in terms of λ1 and λ2. Specifically, λ1 = λ2, λ1 = (1 + λ2)/2 and λ1 = 1 correspond to the dominant, additive, and recessive models, respectively. In a two-dimensional space we can re-parameterize the model by defining λ1 = 1 + λcosθ and λ2 = = 1 + λsinθ, where λ ≥ 0 is the distance between point P = (λ1,λ2) and point O = (1,1), and θ ∈[π/4,π/2] be the angle between OP and the horizontal line (Zheng et al., 2009). Thus, θ determines the genetic model and λ determines how far the genetic model is from the null. The null hypothesis can be rewritten as H0: λ = 0. In terms of genetic models, θ = π/4, arctan 2, and π/2 correspond to dominant, additive, and recessive models, respectively. Note that when θ ∈ (π/2,π), λ1 < 1 and λ2 < 1, it is a heterozygote advantage model, wherein heterozygous individuals have higher fitness than homozygous individuals. A classic example is that the sickle-cell haemoglobin heterozygote provides a protective advantage against malaria (Allison, 1964). In the simulation study below we arbitrarily set θ = 3π/5 as an example of heterozygote advantage model.

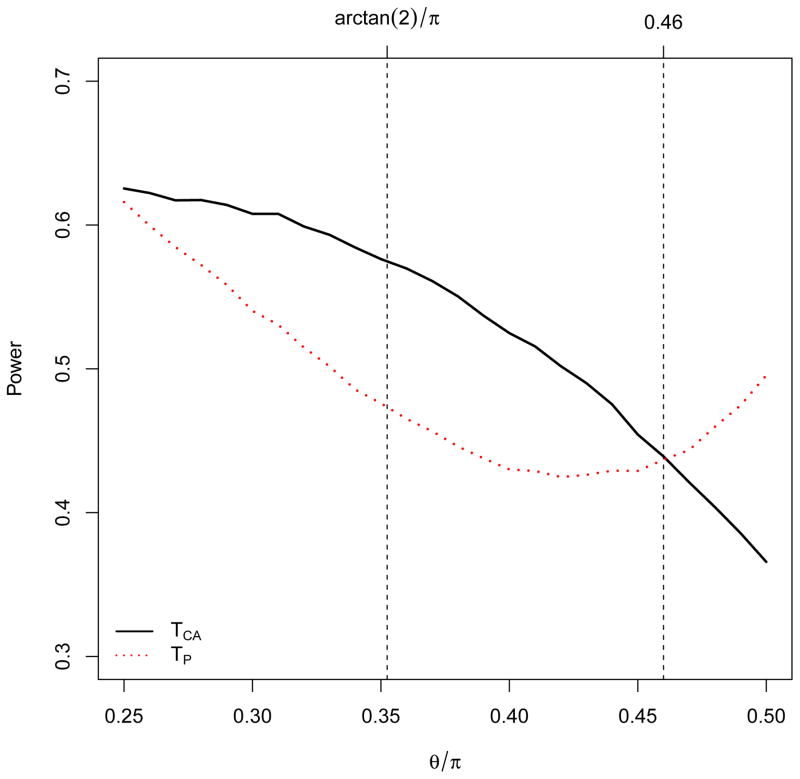

We performed simulations under the following alternative settings. Assume a disease prevalence (K) of 0.1 and the minor allele A frequency (p) of 0.3. Fix the alternative hypothesis as λ = 1 and vary the genetic models by setting θ′ = θ/π from 1/4 to 1/2, i.e., from a dominant model to a recessive model, with an increment of 0.01. Under each genetic model, penetrances are determined by f0 = K/[(1 − p)2 + 2λ1p(1 − p) + λ2p2] and fi = λif0. The probabilities of the two trinomial distributions for cases and controls are then pi = P (Gi)fi/K and qi = P(Gi) (1 − fi)/(1 − K), respectively. The sample size is set to be R = S = 150 such that the power of tests ranges from 0.3 to 0.7 at the test significance level of 0.05. For each model, 10,000 replicates are simulated and each dataset is examined by both tests. When performing the CA trend test, the score set (x0 = 0, x1 = 1/2, x2 = 1) is applied to the three genotypes, i.e., an additive model is assumed by convention. The empirical power at the 0.05 level is calculated as the proportion of the 10,000 replicates for which the P-value is less than or equal to 0.05. The average power over 10 simulations was plotted in Figure 1. Simulations were also performed under the heterozygote advantage model (θ = 3π/5).

Figure 1. Power comparison of the Cochran-Armitage trend test (TCA) and Pearson’s χ2 test (TP).

The solid line denotes TCA and the red dotted line denotes TP. Along the x-axis θ = π/4, arctan 2, and π/2 correspond to dominant, additive, and recessive models, respectively. The y-axis is the average empirical power over 10 simulations at the 0.05 level based on 10,000 replicates each. The disease prevalence equals 0.1; the minor allele frequency equals 0.3; and the sample size is 150 cases and 150 controls.

The results are consistent with previous results (e.g., (Gonzalez et al., 2008; Kuo & Feingold, 2010; Li et al., 2009; Loley et al., 2013) —the CA trend test outperforms Pearson’s χ2 test under a dominant model; the power advantage increases as the genetic model evolves into an additive mode; and then the advantage diminishes as the model keeps evolving toward a recessive mode; around a near recessive model (θ ≅ 0.46π, λ1 ≅ 1.13, λ2 ≅ 1.99), the two tests have similar power; and Pearson’s χ2 test outperforms the CA trend test as the model further evolves toward the recessive mode. Under the heterozygote advantage model (θ = 3π/5) Pearson’s χ2 test is far more powerful than the CA trend test—0.81 versus 0.17.

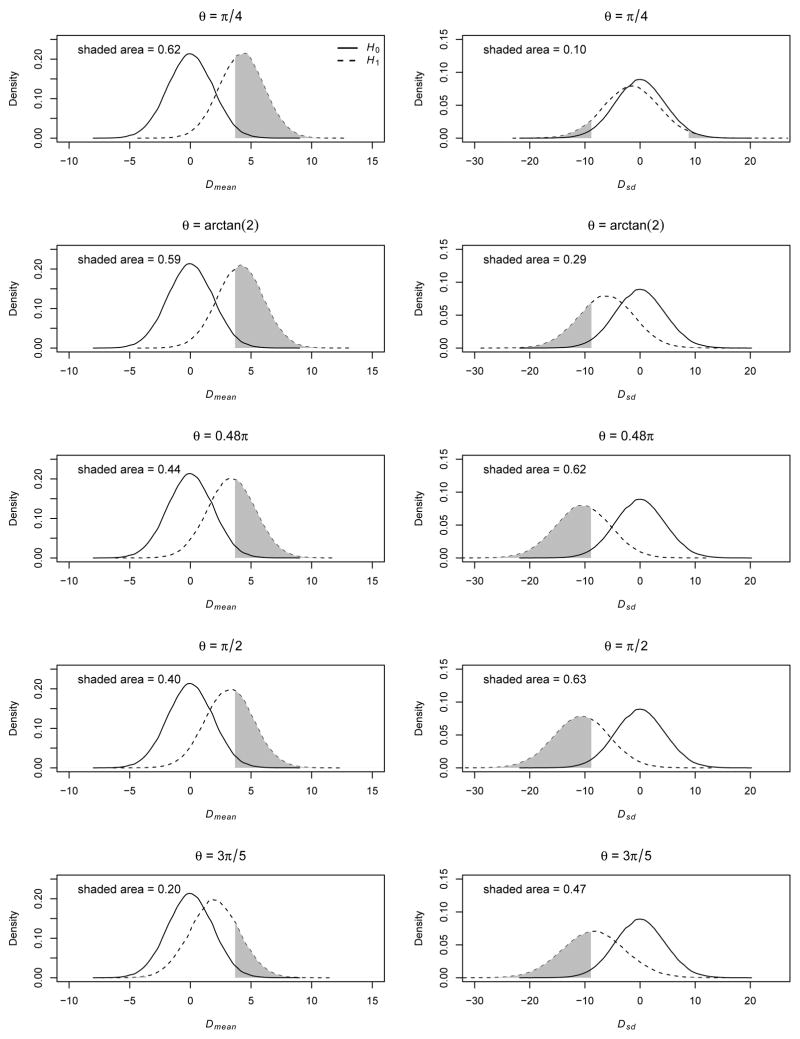

We used two intuitive metrics to measure the location and dispersion shifts of cell counts between cases and controls. The difference of the weighted scores between the two groups, , was used to measure the location shift. The score set (x0 = 0, x1 =1/2, x2 = 1 ) was used. The difference between the standard deviations of the cell counts between the two groups, , where and , was used to measure the dispersion shift. We empirically measured the deviations of these two metrics from the null under five alternative models— a dominant model (θ = π/4, λ1 = λ2 ≅ 1.71) and an additive model (θ = arctan(2), λ1 ≅ 1.45, λ2 ≅ 1.89), under which the CA trend test is more powerful; a near recessive model (θ = 0.48π, λ1 ≅ 1.06, λ2 ≅ 2.00), a recessive model (θ = π/2, λ1 = 1.00, λ2 = 2.00), and a heterozygote advantage model (θ = 3π/5, λ1 ≅ 0.69, λ2 ≅ 1.95), under which Pearson’s χ2 test is more powerful. First, the empirical distribution of each metric under the null hypothesis was obtained based on 100,000 replicates with the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles calculated. Then the empirical distribution under the alternative hypothesis was also calculated based on 100,000 replicates. The area under the alternative distribution curve with values equal to or more extreme than the 97.5% or 2.5% quantiles was calculated, which represented the power of detecting the deviation of the metric from its null distribution at the significance level of 0.05 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Power to detect the location and dispersion shifts of cell counts between cases and controls under additive and near recessive genetic models.

The first row is under a dominant model (θ = π/4, λ1 = λ2 ≅ 1.71); the second row is under an additive model (θ = acrtan (2), λ1 ≅ 1.45, λ2 ≅ 1.89); the third row is under a near recessive model (θ = 0.48π, λ1 ≅ 1.06, λ2 ≅ 2.00); the fourth row is under a recessive model (θ = π/2, λ1 = 1.00, λ2 ≅ 2.00); and the fifth row is under a heterozygote advantage model (θ = 3π/5, λ1 ≅ 0.69, λ2 ≅ 1.95). The first column is on the distribution of Dmean and the second column is on Dsd. The empirical distribution curves are based on 100,000 replicates. The solid line denotes the null distribution and the dashed line denotes the alternative distribution. The critical values for shaded area is are the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles under the null distribution. Note that the area is calculated under both tails but only one tail is visible in most situations.

The power to detect the Dmean and Dsd shifts elucidates the power difference of Pearson’s χ2 test and the CA trend test. Under a dominant model the power to detect the Dsd shift is small—0.10. Accounting for the dispersion information cannot offset the cost of one extra df; thus Pearson’s χ2 test is less powerful. Although the dispersion information increases under an additive model, the CA trend test remains more powerful since it is the most efficient test with correct model assumptions. As the genetic model evolves toward the recessive end, Pearson’s χ2 test becomes more powerful because there is more dispersion information. Under a heterozygote advantage model the CA trend test is less powerful because the location information is small.

Numerous simulation studies showed the 1 df CA trend test is less powerful than the 2 df Pearson’s χ2 test when the mode of inheritance is recessive or near recessive due to the incorrect model assumption, which, as a phenomenon of ‘dog bites man’, is not newsworthy (Elston, 1989). In this paper we analytically reveal the statistical reason of Pearson’s χ2 test outperforming the CA trend test as the genetic model evolves toward the recessive end. We confirm by simulation that under a near recessive model and a recessive model, the effect of dispersion deviation outweighs that of the location deviation. However, it is not a necessary condition for Pearson’s χ2 test to outperform the CA trend test. Rather, the relative power of the two tests depends on whether the gain by taking into account of dispersion information can offset the cost of one extra df. There are tests proposed to simultaneously test location and dispersion (Rayner & Best, 2000; Lang & Iannario, 2013). In a genetic association study involving only 2 × 3 contingency tables as discussed in this paper, these tests are equivalent to Pearson’s χ2 test. When examining contingency tables of 2 × M, where M > 3, for example, when testing association for multi-allelic copy number variations with dosage effects, these tests can potentially be more powerful than Pearson’s χ2 test.

As there is no single best test for all situations (Kuo & Feingold, 2010), researchers have developed the so-called MAX test (Freidlin et al., 2002; Gonzalez et al., 2008; Hothorn & Hothorn, 2009; Li et al., 2008; Loley et al., 2013; So & Sham, 2011; Zang & Fung, 2011), which is more robust than the CA trend test and more powerful than Pearson’s χ2 test. It is worth noting that the MAX test statistic maximized over θ ∈ [π/4, π/2] is identical to Pearson’s χ2 test statistic (Zheng et al., 2009). Its power gain lies in the cost of maximization over one nuisance parameter is smaller than that of one extra df when performing testing.

Acknowledgments

CX was partially supported by the NIH grant UL1TR001105. Author contributions— Study design GX, CX; Theoretical analysis: all authors; Simulation: ZZ, HK, ZH, CX; Manuscript preparation: ZZ, GX, CX.

Appendices

APPENDIX I: Equivalence between the CA trend test statistic TCA and the two-sample mean test statistic Tmean

In Tmean, the numerator . Under the null hypothesis, (r0, r1, r2) and (s0, s1, s2) are independent trinomially distributed vectors with pi = qi = p·i, which are estimated as the homologous sample proportions . The variance of (X̄ − Ȳ) can be derived as . Replacing p·i with , we obtain . Thus .

APPENDIX II: Partitioning TP by orthogonal polynomials

Define vectors Uv = (V1v, V2v)T, where v ∈ {1,2}, N1 = (r0, r1, r2)T, N2 = (s0, s1, s2)T, and . Define matrices H2×3 = [gu(xi)] and , where j = (1, 1, 1). By the definition of Vuv, and . By the properties of the orthonormal polynomials, and H*diag(p)H*T = I3×3. By some matrix manipulation, the latter leads to . Therefore, . Similarly, . Thus .

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Allison AC. Polymorphism and Natural Selection in Human Populations. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1964;29:137–49. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1964.029.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage P. Tests for Linear Trends in Proportions and Frequencies. Biometrics. 1955;11:375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Beh EJ. Partitioning Pearson’s chi-squared statistic for singly ordered two-way contingency tables. Aust Nz J Stat. 2001;43:327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WG. Some methods for strengthening the common chi-square tests. Biometrics. 1954;10:417–451. [Google Scholar]

- Elston RC. Man bites dog? The validity of maximizing lod scores to determine mode of inheritance. Am J Med Genet. 1989;34:487–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320340407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidlin B, Zheng G, Li Z, Gastwirth JL. Trend tests for case-control studies of genetic markers: power, sample size and robustness. Hum Hered. 2002;53:146–52. doi: 10.1159/000064976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JR, Carrasco JL, Dudbridge F, Armengol L, Estivill X, Moreno V. Maximizing association statistics over genetic models. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32:246–54. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn LA, Hothorn T. Order-restricted scores test for the evaluation of population-based case-control studies when the genetic model is unknown. Biom J. 2009;51:659–69. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CL, Feingold E. What’s the best statistic for a simple test of genetic association in a case-control study? Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:246–253. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang JB, Iannario M. Improved tests of independence in singly-ordered two-way contingency tables. Comput Stat Data An. 2013;68:339–351. [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zheng G, Li Z, Yu K. Efficient approximation of P-value of the maximum of correlated tests, with applications to genome-wide association studies. Ann Hum Genet. 2008;72:397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zheng G, Liang X, Yu K. Robust tests for single-marker analysis in case-control genetic association studies. Ann Hum Genet. 2009;73:245–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loley C, Konig IR, Hothorn L, Ziegler A. A unifying framework for robust association testing, estimation, and genetic model selection using the generalized linear model. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:1442–8. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson K. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philosophical Magazine. 1900;50:157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner JCW, Best DJ. Analysis of singly ordered two-way contingency tables. J Appl Math Decision Sci. 2000;4:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sasieni PD. From genotypes to genes: doubling the sample size. Biometrics. 1997;53:1253–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So HC, Sham PC. Robust association tests under different genetic models, allowing for binary or quantitative traits and covariates. Behav Genet. 2011;41:768–75. doi: 10.1007/s10519-011-9450-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang Y, Fung WK. Robust Mantel-Haenszel test under genetic model uncertainty allowing for covariates in case-control association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2011;35:695–705. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Joo J, Yang Y. Pearson’s test, trend test, and MAX are all trend tests with different types of scores. Ann Hum Genet. 2009;73:133–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00500.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]