ABSTRACT

Reassortment of gene segments between coinfecting influenza A viruses (IAVs) facilitates viral diversification and has a significant epidemiological impact on seasonal and pandemic influenza. Since 1977, human IAVs of H1N1 and H3N2 subtypes have cocirculated with relatively few documented cases of reassortment. We evaluated the potential for viruses of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1) and seasonal H3N2 lineages to reassort under experimental conditions. Results of heterologous coinfections with pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses were compared to those obtained following coinfection with homologous, genetically tagged, pH1N1 viruses as a control. High genotype diversity was observed among progeny of both coinfections; however, diversity was more limited following heterologous coinfection. Pairwise analysis of genotype patterns revealed that homologous reassortment was random while heterologous reassortment was characterized by specific biases. pH1N1/H3N2 reassortant genotypes produced under single-cycle coinfection conditions showed a strong preference for homologous PB2-PA combinations and general preferences for the H3N2 NA, pH1N1 M, and H3N2 PB2 except when paired with the pH1N1 PA or NP. Multicycle coinfection results corroborated these findings and revealed an additional preference for the H3N2 HA. Segment compatibility was further investigated by measuring chimeric polymerase activity and growth of selected reassortants in human tracheobronchial epithelial cells. In guinea pigs inoculated with a mixture of viruses, parental H3N2 viruses dominated but reassortants also infected and transmitted to cage mates. Taken together, our results indicate that strong intrinsic barriers to reassortment between seasonal H3N2 and pH1N1 viruses are few but that the reassortants formed are attenuated relative to parental strains.

IMPORTANCE The genome of IAV is relatively simple, comprising eight RNA segments, each of which typically encodes one or two proteins. Each viral protein carries out multiple functions in coordination with other viral components and the machinery of the cell. When two IAVs coinfect a cell, they can exchange genes through reassortment. The resultant progeny viruses often suffer fitness defects due to suboptimal interactions among divergent viral components. The genetic diversity generated through reassortment can facilitate the emergence of novel outbreak strains. Thus, it is important to understand the efficiency of reassortment and the factors that limit its potential. The research described here offers new tools for studying reassortment between two strains of interest and applies those tools to viruses of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 and seasonal H3N2 lineages, which currently cocirculate in humans and therefore have the potential to give rise to novel epidemic strains.

KEYWORDS: H1N1, H3N2, influenza virus, reassortment, segment mismatch

INTRODUCTION

The multipartite genome of influenza A virus (IAV) allows the exchange of gene segments in cells coinfected with multiple variant viruses (1). This process of horizontal gene transfer is termed reassortment and, together with polymerase error, is an important source of viral genetic diversity (2). Reassortment of IAVs adapted to distinct host species has played a prominent role in the emergence of pandemic strains (3, 4). This type of reassortment, involving highly divergent viruses, brings about large shifts in genotype and phenotype, which can facilitate host species transfers (5). In addition, reassortment between cocirculating human IAVs is an important source of genetic diversity in the evolution of seasonal influenza viruses (6–11). In this case, reassortment among related strains can act as a catalyst of viral evolution by allowing point mutations on differing segments to be brought together in a combinatorial manner. Multiple beneficial mutations can thereby be merged within a single genotype, alleviating clonal interference and facilitating the emergence of novel variants (6, 12). This mechanism is thought to have led to widespread resistance to adamantanes within the human H3N2 lineage when a resistance mutation on the M segment was coupled with an HA gene encoding an antigenically novel hemagglutinin (7).

IAVs of H1N1 and H3N2 subtypes have cocirculated in humans since 1977 (13, 14). Prior to 2009, seasonal H3N2 viruses cocirculated with H1N1 viruses of the 1918 lineage. Since 2009, this same H3N2 lineage has cocirculated with viruses derived from the 2009 pandemic. The endemicity of two distinct IAV lineages within the global human population has created the opportunity for coinfection and therefore reassortment between them. Such reassortment has not, however, been detected frequently. Occasional case reports have documented heterosubtypic coinfection in humans, and reassortment was confirmed in a subset of these reports (15–24). Over the past 40 years, few H1N1/H3N2 reassortant viruses have achieved sustained transmission in humans and none have remained prevalent over multiple seasons (25, 26). In contrast, the two major lineages of influenza B virus, Victoria and Yamagata, have exhibited frequent reassortment in humans since their divergence in the 1980s (27, 28). Moreover, intrasubtype reassortment within both H1N1 and H3N2 lineages has given rise to multiple epidemiologically significant strains (6–11, 29). These examples indicate that circulation within human hosts does not preclude coinfection and reassortment of influenza viruses and, therefore, that the rarity with which H1N1/H3N2 reassortant viruses are detected is likely due to evolutionary constraints acting on their heterologous reassortment.

Reassortment between two IAVs that differ in all eight segments can give rise to 256 distinct genotypes. When two divergent strains reassort, however, the diversity generated is often limited by epistasis among gene segments (30). Negative epistatic interactions arising during IAV reassortment are termed “segment mismatch” and may occur at the RNA or protein levels. RNA level mismatches are thought to arise due to sequence divergence in packaging or other cis-acting signals. Incompatibilities among noncognate RNA packaging signals results in preferential incorporation of homologous segment groupings during assembly and can strongly bias the formation of reassortant genotypes (31–33). Protein level mismatches result from suboptimal physical or functional interactions among viral proteins. In contrast to mismatch during genome packaging, incompatibilities among viral proteins are not manifested until after a reassortant virus is formed and goes on to infect another cell. An example of protein mismatch commonly observed is an imbalance between hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) functions (34–36). HA binds cellular sialic acids for viral entry, while NA cleaves sialic acids to allow release at the end of the viral life cycle (37). HA/NA imbalance can therefore lead to poor viral attachment or aggregation at the cell surface (35, 38). The trimeric viral polymerase, comprised of proteins encoded on the PB2, PB1, and PA gene segments, presents another opportunity for protein incompatibilities. Polymerase complexes that derive components from divergent IAV strains are often associated with reduced polymerase activity and/or attenuated viral growth (39–42). Due to the myriad of ways that IAV proteins and functions are interconnected throughout the viral life cycle, the phenomenon of segment mismatch is complex and has been difficult to address in a quantitative or systematic way (43).

Here, we aimed to identify the sources of constraint acting on reassortment between viruses of the seasonal H3N2 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1) lineages. To accomplish this aim, we used a novel strategy in which the genotypes emerging from heterologous coinfection with influenza A/Panama/2007/99 (H3N2) virus and an A/NL/602/2009 (H1N1)-like virus were compared to those observed following homologous coinfection with two closely related pH1N1 viruses. We furthermore employed a comprehensive pairwise analysis of gene segments to systematically identify biases in reassortment. Our results reveal that heterologous coinfections yielded high levels of reassortment but that genotype diversity was lower than seen with the homologous control coinfection. Pairwise analysis of genotype patterns corroborated this observation: homologous reassortment was found to occur randomly, whereas heterologous coinfection was characterized by both subtle and pronounced biases. The functional and fitness implications of several of the segment preferences detected were evaluated by measuring chimeric polymerase activity and by assessing the growth of selected reassortant viruses in human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells. Finally, given that many reassortant gene combinations were detected with high frequency and associated with relatively minor fitness defects in monoculture, we tested the potential for H3N2/pH1N1 reassortants to compete with parental strains in vivo. Inoculation of guinea pigs with a diverse mixture of H3N2/pH1N1 reassortant viruses demonstrated that while the parental H3N2 virus dominated infection, reassortant genotypes were also successfully propagated within the primary host and transmitted to contact animals.

RESULTS

Reassortment between H3N2 and pH1N1 viruses yielded a high diversity of viral genotypes.

We reported previously that reassortment between a tagged version of A/Panama/2007/99 virus (Pan/99wt-His) and a highly homologous variant of the same strain (Pan/99var-HAtag) is efficient, with up to 95% of viruses generated through MDCK cell coinfection carrying reassortant genotypes (44, 45). We also saw that reassortment levels declined with decreasing infectious dose (44, 45). Here, we have built on these earlier findings to design a novel and quantitative means of evaluating reassortment efficiency for two heterologous IAVs. Namely, we evaluated reassortment over a wide range of doses to ensure that reassortment and coinfection readouts were not saturated, we measured infection levels to control for variation in effective multiplicity of infection (MOI), and we compared reassortment levels observed with heterologous viruses to the levels observed following coinfection with homologous wild-type (wt) and variant (var) viruses of the pH1N1 background. Reassortment between these two variants of the same strain served as a control, indicative of baseline reassortment. Taken together, this approach enables quantitative analysis of reassortment efficiency for a relevant pairing of heterologous IAVs and allows meaningful interpretation of these data by comparison to the control data set.

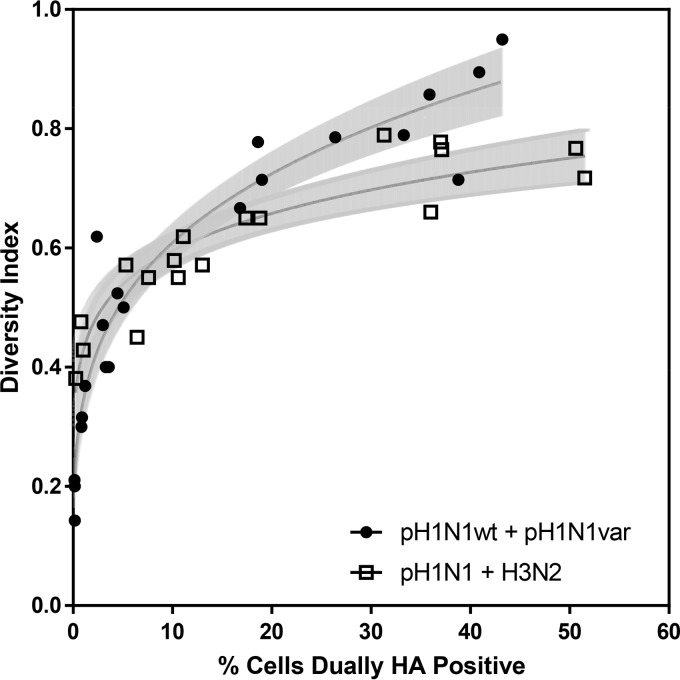

To evaluate reassortment efficiency, coinfections with homologous and heterologous viruses were performed in MDCK cells and limited to a single round of infection. The homologous coinfection included pH1N1wt-HAtag and pH1N1var-His viruses as coinfection partners. The heterologous coinfection included pH1N1wt-HAtag and Pan/99wt-His viruses. As described in Materials and Methods, the pH1N1 viruses used here are based on, but are not identical to, the A/NL/602/2009 (H1N1) strain. These viruses were chosen in part for practical reasons based on the reagents available and, although these particular isolates did not cocirculate, because they are representative of their respective, cocirculating, human lineages. For simplicity, pH1N1wt-HAtag and Pan/99wt-His viruses are here referred to as pH1N1 and H3N2, respectively. Following coinfection, clonal isolates from cell culture supernatants were obtained by plaque assay and genotyped. Based on this experimental design, reassortant gene constellations that do not form, or do not support plaque formation, are not detected. The levels of reassortment observed are represented in Fig. 1 as a diversity index, which is equivalent to the number of unique genotypes identified in a sample divided by the number of isolates screened (46). This diversity index is plotted against the percentage of cells that expressed both viral HA proteins on the cell surface, as detected by flow cytometry. Enumeration of HA-expressing cells was used to monitor the effective MOI. Inclusion of this parameter in the analysis ensures that any differences in reassortment between two coinfections are not due to differing MOIs.

FIG 1.

Diversity of genotypes generated through pH1N1 plus H3N2 reassortment is comparable to that produced by homologous reassortment. Coinfections were performed in MDCK cells over a wide range of MOIs with pH1N1wt-HAtag and pH1N1var-His viruses (closed circles) or pH1N1wt-HAtag and H3N2wt-His viruses (open squares). Infections were limited to a single cycle. Infected cells were enumerated at 24 h postinfection by flow cytometry targeting the His and HA epitope tags. The percentage of cells expressing both epitope tags on the cell surface is plotted on the x axis. The parental origin of each gene segment was determined for plaque isolates from each coinfection culture. The diversity index, plotted on the y axis, is equal to the number of different genotypes identified divided by the number of isolates screened. Each data point resulted from the screening of 17 to 21 plaque isolates, with the exception of the three rightmost data points of each data set, which had 54 to 71 plaque isolates. The curve fits displayed for each data set were determined by nonlinear regression analysis in Prism. Shaded regions define the 95% confidence bands. To evaluate whether the two data sets differ significantly, log-log transformation was used to linearize the data and slopes were determined. The slopes were 0.25 for homologous coinfection and 0.14 for heterologous coinfection (P = 0.0003).

The diversities of genotypes detected following homologous (pH1N1wt-HAtag plus pH1N1var-His) and heterologous (pH1N1 plus H3N2) coinfections were comparable over the lower dosage ranges tested, indicating that reassortment occurs readily between pH1N1 and H3N2. As the percentage of cells that were dually HA positive increased beyond 20%, however, diversity levels attained following heterologous coinfection appeared restricted (Fig. 1). Curve fitting and nonlinear regression confirmed that the homologous and heterologous data sets differed significantly. Specifically, following log-log transformation to linearize the data, the slope of the homologous diversity index was found to increase at a greater rate (P = 0.003). The difference between curves at high levels of infection suggests that fewer reassortant genotypes are viable following heterologous coinfection than after homologous coinfection.

Pairwise analysis of gene segments for the identification of bias in reassortment outcomes.

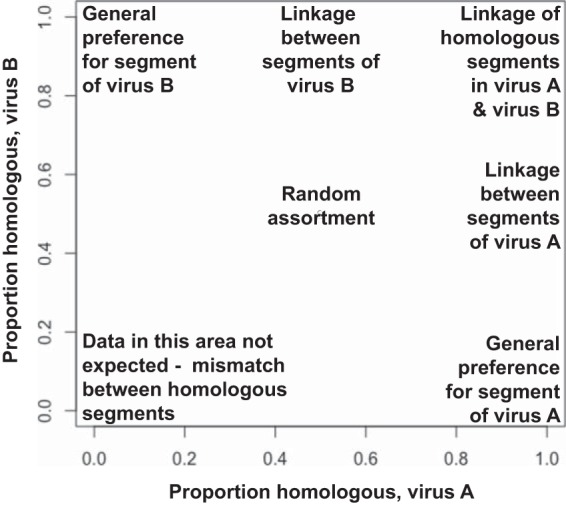

While diversity indices observed following pH1N1 plus H3N2 virus coinfection indicated that appreciable reassortment occurred, the diversity index calculation employed does not allow evaluation of genotype patterns. To identify and quantify biases in reassortment, a more detailed analysis is necessary. One approach would be to test whether all 256 possible genotypes are equally represented among progeny viruses. A more technically feasible approach is to evaluate whether, for a given pair of gene segments, all four possible genotypes are equally represented. For example, when considering PB2 and PB1 segments following infection with parental viruses A and B, progeny viruses could carry AA, AB, BA, or BB genotypes. If reassortment is random, PB2A-carrying viruses would be expected to be 50% AA and 50% AB, while PB2B-carrying viruses would be 50% BA and 50% BB. Performing such an analysis for all pairwise combinations of segments allows detection of favored and disfavored combinations, as well as preferences for particular segments regardless of the gene constellation. To display the results in an easily interpretable fashion, we generated scatterplots for each of the eight segments. Each plot contains seven data points corresponding to the remaining seven segments. To illustrate how this works, we will continue the example given above. On the x axis of the PB2 plot, viruses with PB2A are analyzed and the proportion with an AA combination of PB2 and PB1 is plotted. Thus, if the PB1 data point is at 0.7 on the horizontal axis, the homologous AA combination occurred in 70% of reassortant viruses and the heterologous AB combination was present in 30%. On the y axis of the same plot, viruses with PB2B are examined and the proportion with a BB combination of PB2 and PB1 is plotted. Thus, if the PB1 data point is at 0.7 on the vertical axis, the homologous BB combination was preferred. When data are plotted in this way, one obtains a graphical representation in which segment linkages, or the lack thereof, can be easily identified. Interpretations assigned to different regions of the two-dimensional plot are shown in Fig. 2. Importantly, if reassortment is random, all data points are expected to fall in the middle of the plot, at 0.5 on each axis.

FIG 2.

Pairwise analysis can reveal whether a given segment exchanges freely between viruses, is subject to specific pairwise linkages, or is generally favored or disfavored irrespective of gene constellation. Segments incorporated into reassortant progeny viruses were subjected to a pairwise analysis, and a scatterplot was generated for each of the eight segments. Data points corresponding to each of the other seven segments (segmenti) were plotted. The coinfecting viruses are here termed virus A and virus B. On the PB2 scatterplot, for example, the viruses carrying the PB2 of virus A are analyzed on the x axis and the viruses carrying the PB2 of virus B are analyzed on the y axis. On both axes, the proportion of viruses that carry the homologous combination of PB2 and segmenti (AA or BB) is plotted. The interpretation of data points present in each area of the graph is indicated.

To apply this pairwise analysis to pH1N1wt-HAtag plus pH1N1var-His and pH1N1 plus H3N2 virus pairings, we used genotype data obtained from triplicate coinfections performed at the highest MOI tested in Fig. 1 (i.e., corresponding to the three rightmost data points for each combination of parental viruses). Even at these high MOIs, an appreciable proportion of infected cells were infected with only one parental virus. We therefore excluded parental genotypes from our analyses to avoid biasing results toward homologous combinations. To support a robust analysis, at least 100 clonal isolates per replicate were screened. Following exclusion of parental viruses and any viruses for which one or more segments could not be typed, 54 to 71 viral genotypes per replicate remained. Pairwise analysis was performed separately for each replicate, and then average results were calculated. As detailed in the following sections, results revealed that reassortment between pH1N1wt-HAtag and pH1N1var-His viruses occurred randomly, while reassortment between pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses was characterized by strong pairwise linkages involving PB2 and PA segments and several less pronounced preferences for particular segments or segment combinations.

Homologous reassortment between pH1N1wt-HAtag and pH1N1var-His viruses occurred randomly.

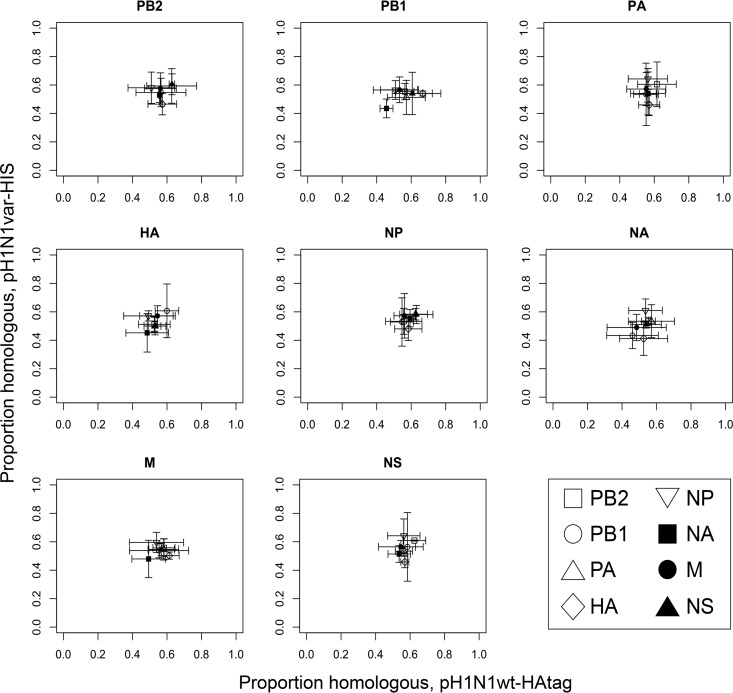

Results of pairwise genotype analysis for pH1N1wt-HAtag plus pH1N1var-His virus reassortment are displayed in Fig. 3. In all eight graphs, the seven data points fall near the midpoint (0.5, 0.5), revealing that genetic exchange between these homologous parental viruses occurred randomly. This observation indicates that coinfecting viral genomes mix freely within the cell at a stage of the viral life cycle that precedes segment bundling (47–49). These results also give a valuable reference for comparison when analyzing data obtained from heterologous coinfection.

FIG 3.

Pairwise analysis of segments incorporated into reassortant progeny indicates that reassortment between pH1N1wt-HAtag and pH1N1var-His viruses is random. The segment analyzed in each scatterplot is indicated above the plot area. On each graph, viruses with the indicated segment from pH1N1wt-HAtag are analyzed on the horizontal axis and viruses with the indicated segment from pH1N1var-His virus are analyzed on the vertical axis. The seven data points indicate the frequency with which homologous pairwise combinations were observed between the segment indicated at the top of the plot and segmenti (as outlined in the legend to Fig. 2). Averages of results from three replicate coinfections are plotted, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

Heterologous reassortment between pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses was nonrandom.

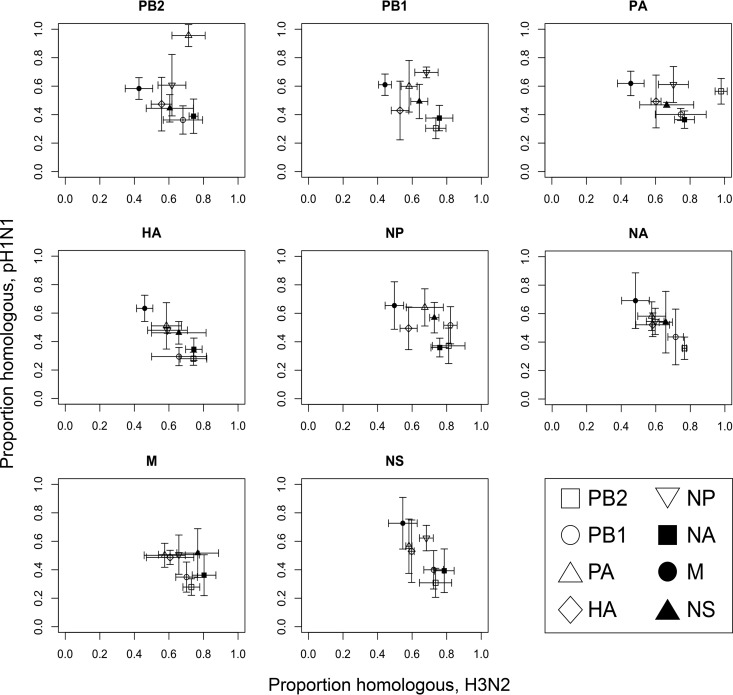

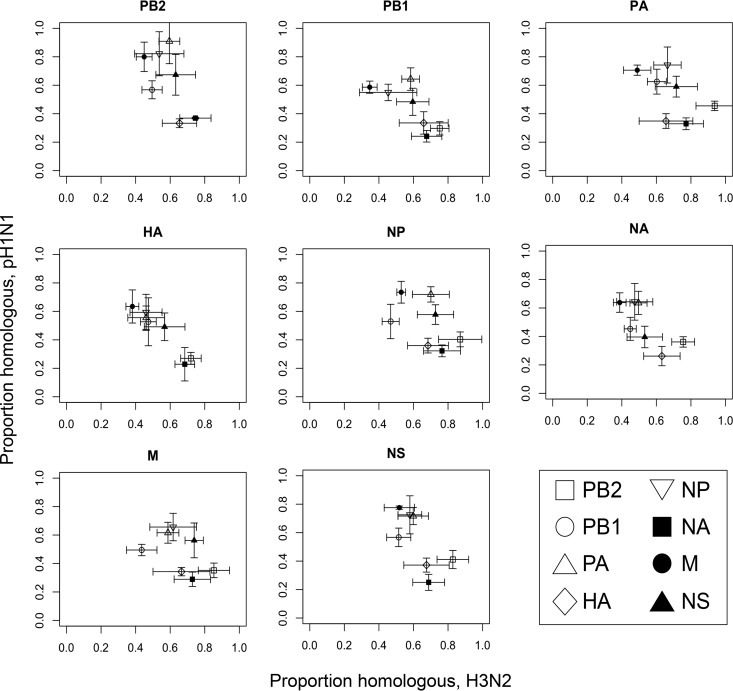

In contrast to results obtained with pH1N1wt-HAtag plus pH1N1var-His viruses, results of pairwise genotype analyses for pH1N1 plus H3N2 virus reassortment revealed evidence of systematic bias in segment assortment. Figure 4 shows the results obtained when coinfections were performed under single-cycle conditions, as used for pH1N1wt-HAtag plus pH1N1var-His coinfection. In addition, we evaluated the genotypes detected following heterologous coinfection performed under conditions that allowed for a second cycle of infection; results of these analyses are shown in Fig. 5. The scatterplots show visually that a number of data points deviate from the center of the graph for pH1N1 plus H3N2 reassortment. To test whether these apparent biases in reassortment were statistically significant, we used the data obtained from pH1N1wt-HAtag plus pH1N1var-His reassortment as a reference for comparison. Specifically, the proportions of reassortant viruses that carried a homologous segment pairing (“proportions homologous”) were compared using Student's t test. Triplicate results for a given pairwise combination from pH1N1 plus H3N2 coinfection were compared to the full data set (triplicate results of all 112 pairings combined) from the pH1N1wt-HAtag plus pH1N1var-His coinfection. Results of these analyses that were common under single-cycle and multicycle conditions are described in the following sections. In general, the outcomes observed under the two coinfection conditions were similar, as indicated by a strong correlation between the data sets (Fig. 6). Two exceptions were noted, however. Under multicycle conditions, the H3N2 HA segment was favored in pairings with both H3N2 and pH1N1 segments, although the pairings with H3N2 were not found to be significant (Table 1). Conversely, both HA segments were detected at approximately equal frequencies under single-cycle conditions. In addition, under single-cycle conditions, the H3N2 PB1 was slightly favored in several pairwise combinations, but multicycle conditions showed that the pH1N1 and H3N2 PB1 segments assorted randomly.

FIG 4.

Pairwise analysis of segments incorporated into reassortant progeny following a single cycle of replication reveals biases in reassortment between pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses. Here, coinfections were performed in the absence of trypsin and with the addition of ammonium chloride at 3 h postinfection. Released virus was sampled at 24 h postinfection. The segment analyzed in each scatterplot is indicated above the plot area. On each graph, viruses with the indicated segment from H3N2 virus are analyzed on the horizontal axis and viruses with the indicated segment from pH1N1 virus are analyzed on the vertical axis. The seven data points indicate the frequency with which homologous pairwise combinations were observed between the segment indicated at the top of the plot and segmenti (as outlined in the legend to Fig. 2). Averages of results from three replicate coinfections are plotted, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

FIG 5.

Pairwise analysis of segments incorporated into reassortant progeny following multiple rounds of replication reveals biases in reassortment between pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses. Here, coinfections were performed in the presence of trypsin and without the addition of ammonium chloride. Released virus was sampled at 24 h postinfection. The segment analyzed in each scatterplot is indicated above the plot area. On each graph, viruses with the indicated segment from H3N2 virus are analyzed on the horizontal axis and viruses with the indicated segment from pH1N1 virus are analyzed on the vertical axis. The seven data points indicate the frequency with which homologous pairwise combinations were observed between the segment indicated at the top of the plot and segmenti (as outlined in the legend to Fig. 2). Averages of results from three replicate coinfections are plotted, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

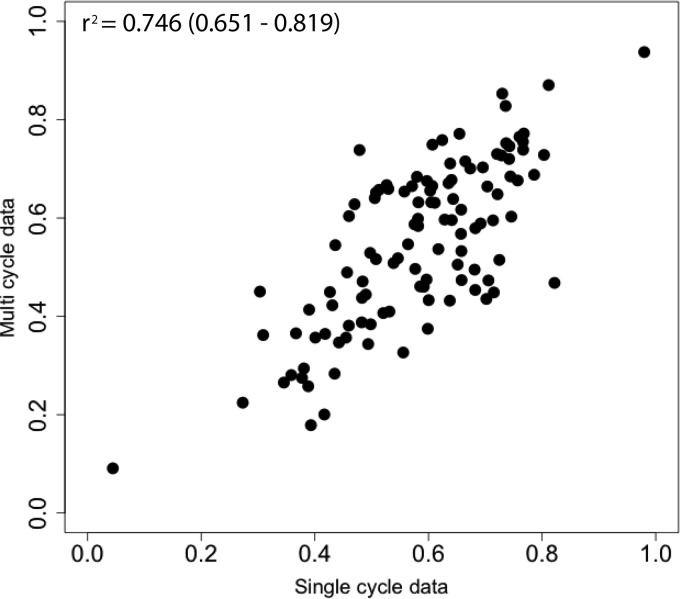

FIG 6.

Results of single-cycle and multicycle coinfections with pH1N1 plus H3N2 viruses are well correlated. Correlation between full data sets was obtained from pairwise analysis of gene segments present in reassortant progeny viruses produced under single-cycle and multicycle conditions. The Pearson correlation coefficient, with 95% confidence interval, is indicated.

TABLE 1.

P values associated with proportion homologous dataa

| Coinfection | Virus and segment |

P value |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | PB1 | PA | HA | NP | NA | M | NS | ||

| Single cycle | pH1N1 PB2 | 0.081 | 0.011 | 0.558 | 0.689 | 0.147 | 0.522 | 0.199 | |

| pH1N1 PB1 | 0.027 | 0.680 | 0.418 | 0.017 | 0.076 | 0.295 | 0.499 | ||

| pH1N1 PA | 0.804 | 0.022 | 0.648 | 0.483 | 0.032 | 0.292 | 0.005 | ||

| pH1N1 HA | 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.719 | 0.017 | 0.045 | 0.255 | 0.194 | ||

| pH1N1 NP | 0.131 | 0.702 | 0.346 | 0.592 | 0.036 | 0.389 | 0.779 | ||

| pH1N1 NA | 0.049 | 0.421 | 0.631 | 0.620 | 0.945 | 0.336 | 0.947 | ||

| pH1N1 M | 0.013 | 0.080 | 0.431 | 0.158 | 0.642 | 0.151 | 0.775 | ||

| pH1N1 NS | 0.054 | 0.194 | 0.898 | 0.894 | 0.291 | 0.219 | 0.232 | ||

| H3N2 PB2 | 0.183 | 0.096 | 0.835 | 0.281 | 0.003 | 0.114 | 0.554 | ||

| H3N2 PB1 | 0.029 | 0.348 | 0.570 | 0.074 | 0.043 | 0.032 | 0.080 | ||

| H3N2 PA | 0.001 | 0.147 | 0.073 | 0.089 | 0.020 | 0.172 | 0.329 | ||

| H3N2 HA | 0.048 | 0.356 | 0.546 | 0.589 | 0.017 | 0.077 | 0.358 | ||

| H3N2 NP | 0.040 | 0.005 | 0.182 | 0.399 | 0.017 | 0.233 | 0.004 | ||

| H3N2 NA | 1.01E-6 | 0.020 | 0.618 | 0.619 | 0.249 | 0.284 | 0.034 | ||

| H3N2 M | 0.021 | 0.049 | 0.741 | 0.544 | 0.252 | 0.022 | 0.088 | ||

| H3N2 NS | 0.073 | 0.031 | 0.065 | 0.010 | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.954 | ||

| Multicycle | pH1N1 PB2 | 0.661 | 0.058 | 0.004 | 0.093 | 1.15E-19 | 0.051 | 0.272 | |

| pH1N1 PB1 | 0.009 | 0.174 | 0.041 | 0.993 | 0.004 | 0.269 | 0.356 | ||

| pH1N1 PA | 0.031 | 0.271 | 0.019 | 0.118 | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.434 | ||

| pH1N1 HA | 0.006 | 0.840 | 0.905 | 0.608 | 0.041 | 0.332 | 0.412 | ||

| pH1N1 NP | 0.037 | 0.799 | 0.029 | 0.021 | 0.009 | 0.050 | 0.554 | ||

| pH1N1 NA | 0.009 | 0.175 | 0.207 | 0.017 | 0.334 | 0.151 | 0.070 | ||

| pH1N1 M | 0.019 | 0.136 | 0.254 | 0.004 | 0.194 | 0.010 | 0.870 | ||

| pH1N1 NS | 0.062 | 0.684 | 0.038 | 0.022 | 0.150 | 0.010 | 9.62E-07 | ||

| H3N2 PB2 | 0.248 | 0.318 | 0.210 | 0.893 | 0.062 | 0.059 | 0.338 | ||

| H3N2 PB1 | 0.020 | 0.364 | 0.311 | 0.423 | 0.128 | 0.012 | 0.481 | ||

| H3N2 PA | 0.024 | 0.230 | 0.357 | 0.127 | 0.061 | 0.319 | 0.142 | ||

| H3N2 HA | 0.035 | 0.098 | 0.286 | 0.237 | 0.051 | 0.012 | 0.812 | ||

| H3N2 NP | 0.047 | 0.100 | 0.132 | 0.186 | 0.072 | 0.296 | 0.098 | ||

| H3N2 NA | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.202 | 0.308 | 0.342 | 0.013 | 0.806 | ||

| H3N2 M | 0.027 | 0.153 | 0.409 | 0.347 | 0.477 | 0.098 | 0.022 | ||

| H3N2 NS | 0.033 | 0.482 | 0.436 | 0.238 | 0.530 | 0.120 | 0.601 | ||

Proportion homologous, proportion of reassortant viruses that carried a homologous segment pairing. Values of <0.05 are in boldface and indicate that proportion homologous values obtained from pH1N1 plus H3N2 coinfection were significantly different from those observed following pH1N1wt plus pH1N1var coinfection (Student's t test).

Viruses combining the pH1N1 PB2 and H3N2 PA segments were detected rarely.

The PB2 scatterplots in Fig. 4 and 5 show that among viruses with the pH1N1 PB2 segment, ∼95% also carried the pH1N1 PA segment (P = 0.011). Similarly, as visible on the PA scatterplots, nearly all reassortant viruses carrying the H3N2 PA also possessed the H3N2 PB2 (P = 0.031). These strong biases suggest that the combination of the pH1N1 PB2 with the H3N2 PA was essentially nonfunctional. The relationship was not reciprocal, however: the PA scatterplots reveal that the pH1N1 PA was paired with PB2 from either parental strain with approximately the same frequency (P = 0.804). Among viruses with the H3N2 PB2, the homologous PA was preferred but not required, with 71% or 60% of viruses carrying the H3N2 PA under single-cycle and multicycle conditions, respectively. This trend did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.058).

PB2 and NA segments from H3N2 virus were favored among reassortant viruses.

Data points in the lower right portion of each scatterplot within Fig. 4 and 5 indicate a preference for the H3N2-derived segment, regardless of whether the partner segment in the pairwise analysis was of H3N2 or pH1N1 virus origin. Under both single-cycle and multicycle conditions, the NA data point was found in this region of all graphs. Statistical analysis indicated significance for most, but not all, pairings compared to the control data set (Table 1). Thus, the proportion of pH1N1 segments that coassorted with the homologous NA was lower than expected while the proportion of H3N2 segments that coassorted with the homologous NA was higher than expected, based on the results of homologous reassortment between pH1N1wt-HAtag and pH1N1var-His viruses.

The PB2 data point also typically fell in the lower right quadrant, with two exceptions: on the PA and NP plots, the PB2 point is at the center right. Thus, the H3N2 PB2 was preferred over the pH1N1 PB2 in all pairwise combinations under both single-cycle and multicycle conditions, except with pH1N1 PA and NP. Viruses with pH1N1 PA or NP carried either PB2 with approximately the same frequency. With few exceptions, preferences for the H3N2 PB2 were statistically significant (P < 0.05; Table 1).

The M segment of the pH1N1 background was compatible with all H3N2 segments and preferred in several pairwise combinations with segments of pH1N1 and H3N2 origin.

Under both single-cycle and multicycle conditions, most of the data points generated through pairwise analysis tended to fall on the right half or in the lower right region of the scatterplots. These patterns reflect biases favoring H3N2 segments together with another H3N2 segment (right side) or together with segments of either strain origin (lower right). The M segment was an exception to this generalization. On a number of plots, the M segment data point fell into the upper half of the graph or into the upper left quadrant, indicating preferences for the pH1N1 M segment over the H3N2 M segment (Fig. 4 and 5). Compared to the control data set, the pH1N1 M segment was significantly preferred in several pairings under multicycle conditions. Under single-cycle conditions, preference for the pH1N1 M segment reached significance only in the pairwise analysis with the H3N2 PB1 segment (Table 1).

Activities of chimeric polymerase complexes suggest that interactions at the protein level underlie reassortment patterns observed among PB2, PB1, PA, and NP segments.

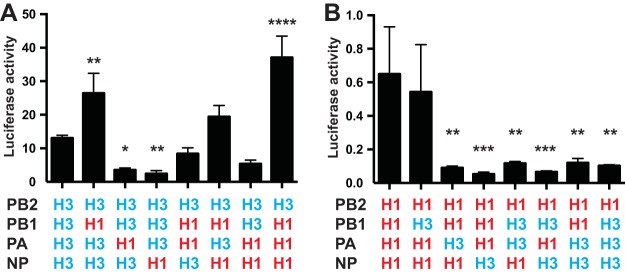

To investigate whether observed reassortment patterns involving pH1N1 and H3N2 PB2, PB1, PA, and NP segments could be attributed to functions of the encoded proteins in replication and transcription of viral RNAs, we evaluated the activities of wild-type and chimeric polymerase complexes in a minireplicon assay. The PB2, PB1, PA, and NP proteins of pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses were coexpressed in all possible combinations with a virus-like segment encoding firefly luciferase. Renilla expression was used as an internal control for transfection efficiency. The average results of three independent experiments, each with 3 technical replicates, are presented in Fig. 7. The wild-type H3N2 polymerase complex supported higher luciferase activity than the wild-type pH1N1 complex by ∼20-fold (P < 0.0001, unpaired t test), and this difference mapped to the PB2 segment. To allow differences not attributable to PB2 to be visualized more easily, data are therefore presented in two separate graphs: polymerase complexes that include the H3N2 PB2 are shown in Fig. 7A, and those that include the pH1N1 PB2 are shown in Fig. 7B. These data sets offered the following insights into the compatibility of pH1N1 and H3N2 polymerase components.

FIG 7.

Activities of chimeric viral polymerase complexes in a minireplicon assay reflect reassortment patterns observed among PB2, PB1, PA, and NP segments. Viral polymerase complexes, comprising PB2, PB1, PA, and NP proteins plus a firefly luciferase reporter template flanked by the NP untranslated regions of WSN virus, were reconstituted by transient transfection of 293T cells. An expression vector encoding Renilla luciferase was included as a control for transfection efficiency, and firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity to yield the values plotted. Each bar represents the average result of nine replicates derived from three transfections. Error bars represent standard deviations. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons was used to evaluate significance relative to the wild-type parental genotype plotted on the same graph. Samples displayed in panels A and B were run in parallel. The strain origin of each viral protein is indicated below the x axis, with H3 representing H3N2 and H1 representing pH1N1. (A) Activity of polymerase complexes with the H3N2 PB2; (B) activity of polymerase complexes with the pH1N1 PB2. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Introduction of the heterologous PB1 segment into either strain background did not reduce polymerase activity, consistent with the observation that this segment assorted randomly between pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses under multicycle coinfection conditions. In contrast, introduction of any other H3N2 segment(s) together with the pH1N1 PB2 markedly reduced activity. Notably, combination of the H3N2 PA segment with PB2, PB1, and NP from pH1N1 virus was unfavorable. This finding offers a mechanistic explanation for the observation that reassortant viruses with pH1N1 PB2 and H3N2 PA segments were detected rarely: low viral fitness likely resulted from poor polymerase function given this combination of PB2 and PA proteins. Finally, the H3N2 PB2 protein supported higher luciferase activity than the pH1N1 PB2 protein even when paired with polymerase components derived from the pH1N1 virus, a result which likely maps to the difference in the PB2 627 domain between these viruses (50) and is consistent with the general preference for the H3N2 PB2 segment observed in our reassortment data set.

Growth in HTBE cell cultures revealed attenuation of reassortant genotypes.

With the aim of testing whether patterns of reassortment observed in MDCK cell coinfection were likely to extend to a coinfected human host, we generated selected reassortant viruses by reverse genetics and evaluated their growth phenotypes in primary, differentiated, HTBE cells (Fig. 8). We attempted to rescue 14 genotypes, including the parental control viruses. Twelve were recovered successfully, while H3N2 virus carrying the pH1N1 PB2 and pH1N1 virus with the H3N2 PA were not. The H3N2:pH1N1 PB2 virus was not rescued in three independent attempts. The pH1N1:H3N2 PA virus rescue yielded a small number of plaques, but we were unsuccessful in amplifying these plaque isolates despite multiple attempts under various conditions. We concluded that these two reassortant genotypes are effectively nonviable, consistent with the results of our pairwise analyses (Fig. 4 and 5).

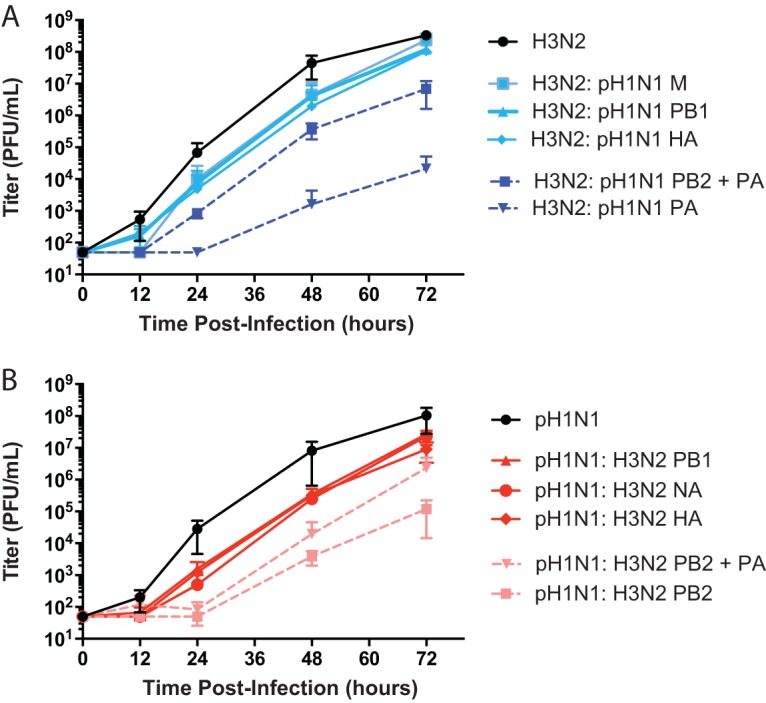

FIG 8.

Growth in HTBE cells revealed attenuation of certain reassortant genotypes. Triplicate wells of fully differentiated HTBE cells were inoculated with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 0.001 PFU/cell and incubated at 33°C. Viral titers present in apical samples collected at the indicated time points were determined by a plaque assay on MDCK cells. The mean result of three replicates is plotted, with the standard deviation indicated by an error bar. (A) Growth of viruses with H3N2-derived PB2 in HTBE cells; (B) growth of viruses with pH1N1-derived PB2 in HTBE cells.

For those reassortant genotypes that were recovered by reverse genetics, growth analyses in HTBE cells revealed that introduction of pH1N1 PB1, HA, or M segments into the H3N2 virus background reduced viral fitness in this system approximately 10-fold (Fig. 8A). By comparison, pairwise analyses of reassortant genotypes showed that the pH1N1 M segment was compatible with all H3N2 segments under both single-cycle and multicycle conditions and that HA and PB1 segments of the two strain backgrounds exchanged freely under single-cycle and multicycle conditions, respectively. This apparent difference between growth and reassortment analyses may reflect the fact that plaque isolates genotyped in our reassortment assay were selected at random, regardless of plaque size. In addition, parental isolates were excluded from the pairwise analysis of genotypes but are included for comparison in the growth analyses. A more extreme fitness defect was seen with introduction of the pH1N1 PA into the H3N2 background. This gene constellation lowered viral yields by >104-fold at the 48- and 72-h time points relative to the H3N2wt control. Parallel introduction of pH1N1 PA and PB2 proteins into the H3N2 background yielded an intermediate phenotype, with 50- to 100-fold lower titers than that of the H3N2wt virus observed in HTBE cells (Fig. 8A). Although reassortant viruses with the H3N2 PB2 tended to carry the homologous PA (Fig. 4), this association was neither strong nor significant, making the severity of the growth defects observed for the H3N2:pH1N1 PA and H3N2:pH1N1 PB2 plus PA viruses unexpected. Importantly, however, pairwise reassortment analyses cannot capture epistatic interactions involving more than two genes. Minireplicon and reassortment data suggest that inclusion of the pH1N1 NP together with pH1N1 PB2 and PA segments may improve viral growth to levels comparable to that of the H3N2wt strain.

Again in the pH1N1 background, the recombinant wild-type strain exhibited the most robust growth (Fig. 8B). Single-gene reassortants in which the H3N2 PB1, HA, or NA segment was introduced showed about 10-fold lower growth in HTBE cells. As noted above, detection of reassortant viruses following coinfection required only that such viruses form visible plaques. The growth data are therefore consistent with reassortment results, which suggested that these three H3N2 segments would be compatible with the pH1N1 background. Introduction of the H3N2 PB2 alone, or together with the H3N2 PA, into the pH1N1 background reduced viral titers by ∼100- to 1,000-fold at the 24-, 48-, and 72-h time points relative to the titer of the pH1N1wt control (Fig. 8B). In contrast, the reassortment and minireplicon data sets suggested that inclusion of the H3N2 PB2 would be favorable in the pH1N1 background. This apparent discrepancy might be attributable to higher-order interactions among segments: the compatibility of H3N2 genes with the pH1N1 background may be dependent on a genetic context that involves more than two genes and therefore cannot be detected through pairwise genotype analyses. In addition, higher polymerase activity, as seen with the H3N2 PB2 in the pH1N1 background, may not be optimal for viral growth.

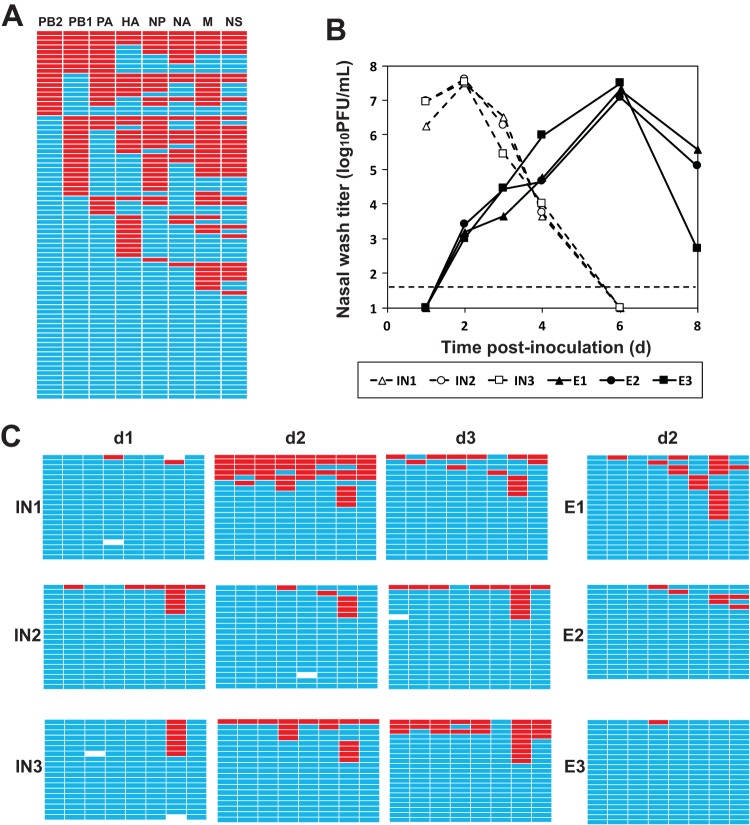

pH1N1/H3N2 reassortant viruses were detected in inoculated and contact guinea pigs following the introduction of a diverse coinfection supernatant into guinea pigs.

As a second means of gauging the relevance of reassortment patterns observed in MDCK cell culture, we evaluated the potential for pH1N1/H3N2 reassortant viruses to propagate within and transmit between guinea pigs. To this end, three guinea pigs were inoculated intranasally with a highly diverse mixture of viruses obtained following single-cycle coinfection of MDCK cells. Namely, the supernatant from the first replicate of our coinfection experiments described above was used as the inoculum. This sample had a diversity index of 0.83; the genotypes detected are shown in Fig. 9A. A relatively high dose of 1 × 105 PFU per guinea pig was used to avoid stochastic reduction of viral diversity upon inoculation. The viral genotypes detected in nasal wash samples obtained from the inoculated animals on days 1, 2, and 3 postinoculation revealed that the H3N2wt genotype dominated the infection but did not render reassortant variants undetectable (limit of detection = 5% frequency in the population). In particular, reassortant viruses carrying the pH1N1 M segment formed an appreciable proportion of the viral population in all three inoculated animals, with up to 43% of M segments sampled of pH1N1 origin (Fig. 9). Transmission to each of the three contact guinea pigs was first detected on day 2 postinoculation (day 1 postexposure). Analysis of viruses isolated from these early positive samples again indicated a fitness advantage for the H3N2wt strain but also revealed reassortant viruses in contact guinea pigs (Fig. 9). Although reassortment in contact animals, rather than transmission of reassortant viruses, could formally account for the detection of nonparental genotypes in the contacts, our prior data on the kinetics of reassortment in guinea pigs strongly suggest that transmission of reassortant viruses occurred (46, 51). Overall, the results of this experiment suggest that the pH1N1 virus and pH1N1:H3N2 reassortants are marginally less fit than the H3N2 parental virus when placed in direct competition.

FIG 9.

Reassortant viruses were detected in inoculated and contact guinea pigs following inoculation with a diverse population of viruses derived from pH1N1:H3N2 coinfection. Three guinea pigs were inoculated intranasally with 1 × 105 PFU of virus derived from a single-cycle coinfection in MDCK cells. At 24 h postinoculation, one naive guinea pig was placed in the same cage with each inoculated animal. (A) Viral genotypes detected in the inoculum included both parental gene constellations and a diverse set of reassortant viruses. Gene segments are identified above each column. Each row represents an individual plaque isolate derived from the coinfection supernatant. Turquoise, H3N2 origin; red, pH1N1 origin. (B) Viral titers detected in nasal washes of inoculated (IN) and exposed (E) animals. Dashed lines represent inoculated animals, and solid lines represent contacts. A horizontal dashed line indicates the limit of detection (50 PFU/ml). (C) Viral genotypes detected in inoculated and exposed guinea pigs. Viral gene segments are represented schematically by eight colored bars arranged horizontally: PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, NA, M, and NS segments are shown from left to right. Turquoise indicates H3N2, red represents pH1N1, and white bars signify segments that could not be typed. The 18 to 21 viral isolates genotyped from each nasal lavage sample are grouped together. The guinea pig from which viruses were collected is indicated on the left. Time after inoculation is indicated in days above each column.

DISCUSSION

The observation that reassortment involving two divergent IAVs proceeds nonrandomly has been documented numerous times (33, 41, 52–62). The biases that characterize heterologous reassortment are indicative of epistatic interactions among gene segments: favored genotypes are typically those that do not break positive interactions by combining segments that have diverged at relevant loci. Put another way, negative epistatic interactions, or instances of “segment mismatch,” constrain viral diversification through reassortment. Despite early recognition of this phenomenon, and its importance in the evolution of pandemic and epidemic IAVs, segment mismatch has rarely been examined in a systematic way. Here we offer two innovations designed to make evaluations of heterologous reassortment more informative.

First, we show that IAV reassortment occurs randomly in the absence of segment mismatch by evaluating the diversity of genotypes generated through reassortment of two highly similar IAVs. (While we previously reported that homologous reassortment was highly efficient [45], analysis of these earlier data to test for randomness was not performed.) This observation reveals that additional constraints on IAV reassortment in coinfected cells are negligible. It furthermore enables rigorous identification of epistatic interactions in heterologous reassortment by providing a baseline for comparison.

Second, we introduced pairwise analysis of gene segments as a means of detecting nonrandom reassortment outcomes. Specifically, for each of the 16 segments present in a coinfection, we determined the proportion of reassortant viruses that carried each of the other segments from the same parental strain. The strengths of this approach include (i) that it is comprehensive, so that any pairwise biases present in the data set are not overlooked, (ii) that the method can be applied to smaller data sets, since any two segments can form a maximum of only four different genotypes, and (iii) that the resultant data can be visualized easily. An important limitation of a pairwise genotype analysis is that epistatic interactions involving three or more segments may not be apparent. While the strategy used here could potentially be expanded to allow the identification of higher-order interactions, a large number of viruses would need to be sampled to give this approach appropriate power (since the number of possible genotypes increases exponentially with the number of segments analyzed).

To demonstrate the utility of these two methodologies, and with the aim of identifying constraints acting on the reassortment of cocirculating human IAVs, we evaluated the outcomes of reassortment between viruses of the pH1N1 and seasonal H3N2 lineages. Our results revealed that this pairing of parental viruses allowed robust diversification through reassortment in MDCK cell culture. When full viral genotypes (rather than pairwise combinations) were considered, the diversity detected following heterologous reassortment was marginally restricted compared to that seen with homologous reassortment. Pairwise analysis allowed the detection of a number of subtle biases, as well as a potent negative interaction involving the pH1N1 PB2 and the H3N2 PA.

Incompatibility among the three polymerase segments and NP from divergent strains has often been noted in the literature (39–41, 55, 60, 63–65). Our own polymerase reconstitution data, and those of others, suggest that these mismatches arise at the protein level and result in reduced polymerase activity (39–41, 64, 65). Indeed, a previous in-depth analysis of the heterologous PB2pH1N1/PAH3N2 pairing revealed impaired replication-initiation relative to that of the full pH1N1 polymerase complex, which mapped largely to PAH3N2 residues 184N and 383N (40). The relatively free exchange of PB1 segments between pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses seen here is likely due to the fact that they are closely related: the PB1 segment of the pH1N1 lineage is derived from the human seasonal H3N2 lineage (66, 67). In contrast to a number of reports in which heterologous HA/NA combinations have been found to yield viruses with fitness defects (34–36, 68, 69), we did not note negative interactions between pH1N1 and H3N2 virus HA and NA genes. While this finding may be attributable in part to the use of MDCK cells, the phenotypes of selected reassortant viruses in HTBE cells indicate that heterologous HA/NA combinations did not exert a major fitness cost in this setting as well.

Despite the observation that pronounced biases in pH1N1:H3N2 reassortment were limited, multicycle growth analyses of selected reassortants in HTBE cells revealed a clear advantage of parental genotypes. In vivo, inoculation of guinea pigs with a diverse mixture of reassortant viruses indicated that the H3N2 parental strain in particular was predominant. These results are consistent with only sporadic detection of pH1N1:H3N2 reassortant viruses within the human population, despite their cocirculation over an 8-year period. The observed phenotypes in HTBE cells and guinea pigs underline the fact that minor fitness defects can be highly significant when amplified over many rounds of viral replication and when multiple variant viruses are in direct competition. The subtle biases in pH1N1:H3N2 reassortment noted here may therefore play a major role in limiting the success of intersubtypic reassortant viruses within the human population.

Despite often complex linkages among gene segments, genetic exchange between diverse IAV lineages has been documented repeatedly in nature (6, 8, 10, 11, 70–73). In these cases, selection pressures imposed by the host environment might favor a reassortant virus, thereby offsetting fitness defects due to segment mismatch. In addition, frequent errors in RNA replication allow incompatibilities among viral proteins or packaging signals to be alleviated through postreassortment adaptive changes (36, 74, 75). With these concepts in mind, it is notable that several reassortant genotypes were detected in guinea pigs with mixed pH1N1-H3N2 infection and transmitted to cage mates. These data imply that similar reassortants could be sufficiently fit to achieve sustained spread in humans if changing selection pressures reduce competition from parental viruses. Indeed, the prevalence of reassortant viruses incorporating the pH1N1 M segment in global swine populations suggests that the strong representation of this segment in our in vivo study may be indicative of its potential to penetrate the human H3N2 lineage (76–78).

In sum, we offer a rigorous means of evaluating the potential for heterologous reassortment to give rise to fit influenza virus variants. We furthermore show that genetic exchange between representative strains of pH1N1 and seasonal H3N2 lineages yields a diverse range of reassortant genotypes but that these reassortants are attenuated relative to the parental strains. We propose that the observed fitness defects are likely to be highly significant on an epidemiological scale but also could be overcome through reduced competition from parental strains and/or mutation of mismatched gene segments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (a kind gift of Peter Palese, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) were maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin. 293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216) were maintained in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells from a single donor were acquired from Lonza and were amplified and differentiated into air-liquid interface cultures as recommended by Lonza and described by Danzy et al. (79).

Viruses.

All viruses used in this work were generated using reverse genetics techniques (80). The rescue system for A/Panama/2007/99 (H3N2) (Pan/99) virus was initially described in reference 81, and that for A/Netherlands/602/2009 (H1N1) (NL/09) virus was a gift of Ron Fouchier (Erasmus Medical Center) (82). The passage history of Pan/99 virus includes egg passage, as it previously served as a vaccine strain, while the NL/09 virus was derived from a primary human specimen prior to the cloning of the viral cDNA to generate the reverse genetics system (82). The Pan/99wt-His virus was described previously (45) and is modified from the wild-type Pan/99 sequence through the inclusion of a His epitope tag plus GGGS linker at the N terminus of the HA protein (inserted after the signal peptide). The pH1N1wt-HAtag and pH1N1var-His viruses carry similarly modified HA genes, with the HA tag or His tag, respectively, plus a GGGS linker inserted at the N terminus of the NL/09 HA protein. These two viruses also carry PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M, and NS gene segments of the NL/09 strain. Due to the unusually low neuraminidase activity associated with the NL/09 NA protein (83), we replaced the NL/09 NA segment with that of influenza A/CA/04/2009 (H1N1) virus. The NL/09 and A/CA/04/2009 NA proteins differ by two amino acids. These two substitutions were found to increase the growth rate of the resultant pH1N1 viruses relative to the unmodified NL/09 strain (data not shown), which was important for allowing detection of pH1N1 genes in the context of coinfection with Pan/99 virus. In addition to the His tag and linker inserted into the HA protein, the pH1N1var-His virus carries a single synonymous mutation per segment relative to the pH1N1wt-HAtag virus, as follows: PB2 C273T, PB1 T288C, PA C360T, HA C305T, NP A351G, NA G336A, M G295A, and NS C341T. These eight silent mutations act as genetic markers for determining the parental origin of gene segments following the isolation of progeny viruses from coinfected cells.

To evaluate the growth of selected H3N2:pH1N1 reassortant viruses in HTBE cells, viruses were generated by reverse genetics using the appropriate pPOL1 Pan/99 and pHW NL/09 plasmids. Where the pH1N1 NA segment was included, the pPOL1 CA/04/09 NA plasmid was used. Support plasmids encoding WSN PB2, PB1, PA, or NP proteins in pCAGGS were included in rescue transfections as needed. This set of viruses did not include variant mutations or epitope tags.

Pan/99wt-His virus was cultured in 9- to 11-day-old embryonated chicken eggs incubated at 33°C. All other viruses were grown in MDCK cells incubated at 33°C. Since the presence of defective interfering RNAs in the context of coinfection could result in misleading preferences for segments of a certain parental origin, care was taken to limit their accumulation. Viruses were cultured at a low MOI and maintained at a low passage number (passaged once or twice following rescue or plaque purification in MDCK cells). The levels of defective interfering segments derived from PB2, PB1, and PA segments of all virus stocks used in coinfection were assessed by droplet digital PCR as described in reference 84 and found to be minimal.

Coinfection with homologous or heterologous virus pairs.

MDCK cells were seeded at 4 × 105 cells/well in 6-well dishes 18 to 24 h prior to infection. Appropriate viruses were combined at a high titer and then serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to achieve a range of MOIs (10, 6, 3, 1, 0,6, 0.3, or 0.1 PFU/cell). The ratio of HA-positive cells detected by flow cytometry was used to optimize the proportion of each virus used in a mixture. Namely, a 1:1 ratio of HA tag-positive cells to His tag-positive cells following a single cycle of replication in the presence of NH4Cl was sought. In terms of PFU titer, the ratios used were 1:1 (pH1N1wt-HAtag and pH1N1var-His) for homologous coinfections and 5:1 (pH1N1wt-HAtag and Pan/99wt-His, respectively) for heterologous coinfections. Triplicate wells were inoculated at each MOI. Inoculation was performed on ice, and dishes were incubated at 4°C for 45 to 50 min to allow attachment. After removal of the inoculum, cells were washed three times with cold PBS and then warm virus medium (MEM supplemented with 3% bovine serum albumin and penicillin-streptomycin) was added. After 3 h of incubation at 33°C, virus medium was changed to either (i) virus medium supplemented with 1 M NH4Cl for single-cycle growth or (ii) virus medium supplemented with 1 μg/ml trypsin for multicycle growth. Cells were harvested and supernatant was collected at 24 h postinfection.

Determination of infection levels based on HA surface expression.

To enumerate infected cells, surface expression of His and HA epitope tags was detected by flow cytometry. This method was previously described in detail (45). The percentage of cells that were positive for both epitope tags is expressed as a percentage of cells dually HA positive in Fig. 1.

Determination of reassortment levels.

The following protocol was used to characterize the diversity of viral genotypes present in supernatants from cell culture coinfections and in nasal washes from guinea pigs. Plaque assays were performed in 10-cm cell culture dishes to isolate viral clones. For pH1N1 plus H3N2 coinfection samples, where plaque size was heterogeneous, all plaques on a dish were marked while holding the dish up to the light. The plate was then placed on a surface (where plaque size is not visible), and 5-ml serological pipettes were used to collect the agar plugs overlaying plaques selected at random. Each agar plug was dispensed into 160 μl PBS. RNA was extracted from these 160-μl samples by using a ZR-96 viral RNA kit (Zymo Research) and eluted in 40 μl water. Reverse transcription was performed with Maxima RT (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 1:4 dilution in water, each cDNA was combined with segment-specific primers and Precision Melt Supermix (Bio-Rad) and analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR), followed by high-resolution melt (HRM) analysis in a CFX384 Touch real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Primers used to differentiate the gene segments of pH1N1wt-His and pH1N1var-HAtag viruses amplify an ∼100-bp region of each gene segment, which contains the site at which a single nucleotide change was introduced into the pH1N1var-HAtag virus (Table 2). Primers used to differentiate the gene segments of pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses bind to sequences conserved between these two strains and amplify an ∼100-bp region that differs by at least one nucleotide between the two strains (Table 2). The sequence differences in these amplicons confer differences in melting properties to the cDNA, which is the basis of the HRM genotyping method. Thus, Precision Melt Analysis software (Bio-Rad) was used to determine the parental virus origin of each gene segment based on melting properties of the cDNAs. The HRM genotyping method is also described in references 44, 45, and 51. The HA and NA segments of pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses did not contain conserved regions of sufficient length to allow for the design of common primers. For this reason, HA and NA segments in samples derived from heterologous coinfection were genotyped by conventional qPCR with strain-specific primers. The sequences of all primers used for genotyping are given in Table 1. For each coinfection supernatant or guinea pig nasal wash sample analyzed in this way, at least 17 and typically up to 21 plaque isolates were analyzed. To generate data used in pairwise analysis, this sample number was increased.

TABLE 2.

Primers used to genotype progeny isolated from mixed infections

| Parental virus pairing | Primer namea | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| pH1N1wt plus pH1N1var | NL PB2 247 F | GGACAAACCCTCTGGAGCAA |

| NL PB2 315 R | TACGGCCAGAGGTGATACCA | |

| NL PB1 225 F | CCCGATTGATGGACCACTACC | |

| NL PB1 311 R | TCAAGGAAAGCCATAGCCTCT | |

| NL PA 313 F | ACAACAGGGGTAGAGAAGCC | |

| NL PA 410 R | ATGTGGACTTCCCTCCGTGT | |

| NL HA 282 F | TGTGAATCACTCTCCACAGCA | |

| NL HA 361 R | CCTGGGTAACACGTTCCATTG | |

| NL NP 309 F | CCCTAAGAAAACAGGAGGACCC | |

| NL NP 411 R | TTGGCGCCAAACTCTCCTTA | |

| NL NA 293 F | CTGCCCTGTTAGTGGATGGG | |

| NL NA 368 R | GACAAACACATCCCCCTTGG | |

| NL M 256 F | ACGCTTTGTCCAAAATGCCC | |

| NL M 364 R | CTTGGCCCCATGGAACGTTA | |

| NL NS 320 F | GTCACGAGACTGGTTCATGC | |

| NL NS 389 R | CTGGTCCAATCGCACGCAAA | |

| pH1N1 plus H3N2 | P99 NL PB2 101 F | GTGGACCATATGGCCATAAT |

| P99 NL PB2 187 R | TCATTGCCATCATCCARTTCAT | |

| P99 NL PB1 809 F | TTTGCGAAAAGCTTGAACAG | |

| P99 NL PB1 912 R | TGTGTCTTGTGAATTAGTCATCATC | |

| P99 NL PA 601 F | CAGTCCGAAAGAGGCGAAG | |

| P99 NL PA 755 R | CCCTCAATGCAGCCGTTC | |

| P99 NL NP 161 F | CTACATCCAAATGTGCACTG | |

| P99 NL NP 270 R | CTTCTCTCATCAAAAGCAGA | |

| P99 NL M 145 F | GGCTCTCATGGAATGGCTAA | |

| P99 NL M 258 R | CGTCTACGCTGCAGTCCTC | |

| P99 NL NS 539 F | TGAGGATGTCAAAAATGCA | |

| P99 NL NS 639 R | TTCTCCAAGCGAATCTCTGT | |

| P99 HA 802 F | ATTGCTCCTCGGGGTTACTT | |

| P99 HA 926 R | GGTTTGTCATTGGGAATGCT | |

| P99 NA 408 F | ATCAATTTGCCCTTGGACAG | |

| P99 NA 517 R | TGGAACACCCAACTCATTCA | |

| NL HA 345 F | GGAACGTGTTACCCAGGAGA | |

| NL HA 459 R | GATTGGGCCATGAACTTGTC | |

| NL NA 296 F | CCCTGTTAGTGGATGGGCTA | |

| NL NA 397 R | GGGGAGCATGATATGAATGG |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Pairwise analysis of gene segments.

As a means of detecting bias in reassortment outcomes, a pairwise analysis of segments incorporated into reassortant progeny viruses was performed. The genotype tables included as Data Set S1 in the supplemental material report the raw data used. An R script was written to perform the following functions on each of the replicate data sets and then compute and plot the average and standard deviation of the triplicate values. The coinfecting parental viruses, and the segments they carry, were designated “0” and “1.” The script first identified all reassortant viruses with PB2 of type 0 and then determined what proportion of those viruses also carried segmenti of type 0 (where segmenti represents each of the other segments). This step yielded a set of seven “proportion homologous” values for PB2 from virus 0. Similarly, the proportion of viruses with PB2 of type 1 that also carried segmenti of type 1 was then calculated. This process was repeated for all segments, giving seven “proportion homologous” values for each of the 16 segments examined (eight from virus 0 and eight from virus 1). These results were plotted on a set of eight scatterplots, with the proportion homologous from virus 0 on the x axis and the proportion homologous from virus 1 on the y axis.

Statistical analyses of these data were also performed in R. Unpaired Student's t tests were used to evaluate whether proportion homologous values observed following heterologous coinfection differed significantly from those observed following homologous coinfection. Since all possible pairwise combinations resulting from homologous coinfection were functionally homologous, the full set of 336 proportion homologous values (8 segments × 2 viruses × 7 segmenti × 3 replicates = 336) was included in these t tests as the comparator for each set of three proportion homologous values obtained from heterologous coinfection. The correspondence between results obtained from the heterologous coinfections performed under single-cycle and multicycle conditions was assessed in R using Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient.

Polymerase reconstitution assay.

293T cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells/well in 24-well dishes and incubated for 18 to 24 h at 37°C. Cells were then transfected with 9 μl X-treme Gene 9 transfection reagent (Roche) and 500 ng of each plasmid in Opti-MEM. Each well received six plasmids, as follows: pPOL1 NP luc (encoding, in the negative sense, firefly luciferase flanked by the NP untranslated regions of influenza A/WSN/1933 virus), pRL-TK (encoding Renilla luciferase under the control of a thymidine kinase promoter), pCAGGS PB2, pCAGGS PB1, pCAGGS PA, and pCAGGS NP. Plasmids encoding the viral polymerase components carried genes from either Pan/99 or NL/09, as indicated in Fig. 7. Transfections were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Following incubation, medium was removed from cells and Dual-Glo luciferase assay reagent (Promega) was added and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Lysate aliquots of 100 μl from each reaction were added in triplicate to a 96-well plate (Costar), and firefly luminescence was read using a microplate reader (Biotek Synergy H1 hybrid reader). Stop & Glo substrate (Promega) was then added and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Following incubation, Renilla luciferase luminescence was measured as described above. The ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase readouts was calculated for each sample and expressed as normalized polymerase activity. Three technical replicates were included in each transfection, and the experiment was performed on three different days.

Viral growth in HTBE cells.

Human tracheobronchial epithelial (HTBE) cells (Lonza) at least 4 weeks after differentiation into air-liquid interface cultures were used to assess virus growth. Immediately prior to infection, mucus was aspirated and the cell monolayer was washed three times with PBS. Cells were then inoculated with virus diluted in PBS to an MOI of 0.001 PFU/cell and incubated for 1 h at 33°C. Subsequently, the inoculum was removed and the cell monolayer was washed three times with PBS. To sample virus, 200 μl PBS was added to each well and incubated for 30 min before collection. Samples were taken at 1, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection. Virus growth was quantified by plaque assay.

Viral growth and transmission in guinea pigs.

Female Hartley strain guinea pigs weighing 300 to 350 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Prior to inoculation or nasal lavage, animals were sedated with a mixture of ketamine (30 mg/kg) and xylazine (4 mg/kg). Virus used for inoculation was a cell culture supernatant derived from single-cycle coinfection with Pan/99wt-His and pH1N1wt-HAtag viruses. This supernatant was diluted in PBS to allow intranasal inoculation of guinea pigs with 1 × 105 PFU in a 300-μl volume. One contact guinea pig was introduced into the same cage with each of the inoculated animals at 24 h postinoculation. Nasal wash samples were collected as described previously (85), with PBS as the collection fluid. Animals were housed in a Caron 6040 environmental chamber set to 10°C and 20% relative humidity throughout the 7-day exposure period, and lids were left off the cages during this time to ensure environmental control within the cages (86).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Seema Lakdawala for helpful discussion.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under grants R01AI099000 and R01AI125268 to A.C.L. and by the Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS) contract HHSN272201400004C to A.C.L. and J.S. K.L.P. is currently supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32AI106699.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00830-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desselberger U, Nakajima K, Alfino P, Pedersen FS, Haseltine WA, Hannoun C, Palese P. 1978. Biochemical evidence that “new” influenza virus strains in nature may arise by recombination (reassortment). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 75:3341–3345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scholtissek C. 1995. Molecular evolution of influenza viruses. Virus Genes 11:209–215. doi: 10.1007/BF01728660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taubenberger JK, Kash JC. 2010. Influenza virus evolution, host adaptation, and pandemic formation. Cell Host Microbe 7:440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schrauwen EJ, Fouchier RA. 2014. Host adaptation and transmission of influenza A viruses in mammals. Emerg Microbes Infect 3:e9. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma EJ, Hill NJ, Zabilansky J, Yuan K, Runstadler JA. 2016. Reticulate evolution is favored in influenza niche switching. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:5335–5339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522921113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes EC, Ghedin E, Miller N, Taylor J, Bao Y, St George K, Grenfell BT, Salzberg SL, Fraser CM, Lipman DJ, Taubenberger JK. 2005. Whole-genome analysis of human influenza A virus reveals multiple persistent lineages and reassortment among recent H3N2 viruses. PLoS Biol 3:e300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson MI, Simonsen L, Viboud C, Miller MA, Holmes EC. 2009. The origin and global emergence of adamantane resistant A/H3N2 influenza viruses. Virology 388:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson MI, Viboud C, Simonsen L, Bennett RT, Griesemer SB, St George K, Taylor J, Spiro DJ, Sengamalay NA, Ghedin E, Taubenberger JK, Holmes EC. 2008. Multiple reassortment events in the evolutionary history of H1N1 influenza A virus since 1918. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000012. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rambaut A, Pybus OG, Nelson MI, Viboud C, Taubenberger JK, Holmes EC. 2008. The genomic and epidemiological dynamics of human influenza A virus. Nature 453:615–619. doi: 10.1038/nature06945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simonsen L, Viboud C, Grenfell BT, Dushoff J, Jennings L, Smit M, Macken C, Hata M, Gog J, Miller MA, Holmes EC. 2007. The genesis and spread of reassortment human influenza A/H3N2 viruses conferring adamantane resistance. Mol Biol Evol 24:1811–1820. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westgeest KB, Russell CA, Lin X, Spronken MIJ, Bestebroer TM, Bahl J, van Beek R, Skepner E, Halpin RA, de Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus ADME, Smith DJ, Wentworth DE, Fouchier RAM, de Graaf M. 2014. Genome-wide analysis of reassortment and evolution of human influenza A(H3N2) viruses circulating between 1968 and 2011. J Virol 88:2844–2857. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02163-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ince WL, Gueye-Mbaye A, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. 2013. Reassortment complements spontaneous mutation in influenza A virus NP and M1 genes to accelerate adaptation to a new host. J Virol 87:4330–4338. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02749-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young JF, Desselberger U, Palese P. 1979. Evolution of human influenza A viruses in nature: sequential mutations in the genomes of new H1N1. Cell 18:73–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhdanov VM, Lvov DK, Zakstelskaya LY, Yakhno MA, Isachenko VI, Braude NA, Reznik VI, Pysina TV, Andreyev VP, Podchernyaeva RY. 1978. Return of epidemic A1 (H1N1) influenza virus. Lancet i:294–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamane N, Arikawa J, Odagiri T, Sukeno N, Ishida N. 1978. Isolation of three different influenza A viruses from an individual after probable double infection with H3N2 and H1N1 viruses. Jpn J Med Sci Biol 31:431–434. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.31.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falchi A, Arena C, Andreoletti L, Jacques J, Leveque N, Blanchon T, Lina B, Turbelin C, Dorleans Y, Flahault A, Amoros JP, Spadoni G, Agostini F, Varesi L. 2008. Dual infections by influenza A/H3N2 and B viruses and by influenza A/H3N2 and A/H1N1 viruses during winter 2007, Corsica Island, France. J Clin Virol 41:148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendal AP, Lee DT, Parish HS, Raines D, Noble GR, Dowdle WR. 1979. Laboratory-based surveillance of influenza virus in the United States during the winter of 1977-1978. II. Isolation of a mixture of A/Victoria- and A/USSR-like viruses from a single person during an epidemic in Wyoming, U S A, January 1978. Am J Epidemiol 110:462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizuta K, Katsushima N, Ito S, Sanjoh K, Murata T, Abiko C, Murayama S. 2003. A rare appearance of influenza A(H1N2) as a reassortant in a community such as Yamagata where A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) co-circulate. Microbiol Immunol 47:359–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rith S, Chin S, Sar B, Y P, Horm SV, Ly S, Buchy P, Dussart P, Horwood PF. 2015. Natural co-infection of influenza A/H3N2 and A/H1N1pdm09 viruses resulting in a reassortant A/H3N2 virus. J Clin Virol 73:108–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu W, Li ZD, Tang F, Wei MT, Tong YG, Zhang L, Xin ZT, Ma MJ, Zhang XA, Liu LJ, Zhan L, He C, Yang H, Boucher CA, Richardus JH, Cao WC. 2010. Mixed infections of pandemic H1N1 and seasonal H3N2 viruses in 1 outbreak. Clin Infect Dis 50:1359–1365. doi: 10.1086/652143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers CA, Kasper MR, Yasuda CY, Savuth C, Spiro DJ, Halpin R, Faix DJ, Coon R, Putnam SD, Wierzba TF, Blair PJ. 2011. Dual infection of novel influenza viruses A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 in a cluster of Cambodian patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85:961–963. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frank AL, Taber LH, Wells JM. 1983. Individuals infected with two subtypes of influenza A virus in the same season. J Infect Dis 147:120–124. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poon LL, Song T, Rosenfeld R, Lin X, Rogers MB, Zhou B, Sebra R, Halpin RA, Guan Y, Twaddle A, DePasse JV, Stockwell TB, Wentworth DE, Holmes EC, Greenbaum B, Peiris JS, Cowling BJ, Ghedin E. 2016. Quantifying influenza virus diversity and transmission in humans. Nat Genet 48:195–200. doi: 10.1038/ng.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young JF, Palese P. 1979. Evolution of human influenza A viruses in nature: recombination contributes to genetic variation of H1N1 strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76:6547–6551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen MJ, La T, Zhao P, Tam JS, Rappaport R, Cheng SM. 2006. Genetic and phylogenetic analysis of multi-continent human influenza A(H1N2) reassortant viruses isolated in 2001 through 2003. Virus Res 122:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gregory V, Bennett M, Orkhan MH, Al Hajjar S, Varsano N, Mendelson E, Zambon M, Ellis J, Hay A, Lin YP. 2002. Emergence of influenza A H1N2 reassortant viruses in the human population during 2001. Virology 300:1–7. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudas G, Bedford T, Lycett S, Rambaut A. 2015. Reassortment between influenza B lineages and the emergence of a coadapted PB1-PB2-HA gene complex. Mol Biol Evol 32:162–172. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rota PA, Wallis TR, Harmon MW, Rota JS, Kendal AP, Nerome K. 1990. Cocirculation of two distinct evolutionary lineages of influenza type B virus since 1983. Virology 175:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson MI, Edelman L, Spiro DJ, Boyne AR, Bera J, Halpin R, Sengamalay N, Ghedin E, Miller MA, Simonsen L, Viboud C, Holmes EC. 2008. Molecular epidemiology of A/H3N2 and A/H1N1 influenza virus during a single epidemic season in the United States. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000133. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips PC. 2008. Epistasis—the essential role of gene interactions in the structure and evolution of genetic systems. Nat Rev Genet 9:855–867. doi: 10.1038/nrg2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Essere B, Yver M, Gavazzi C, Terrier O, Isel C, Fournier E, Giroux F, Textoris J, Julien T, Socratous C, Rosa-Calatrava M, Lina B, Marquet R, Moules V. 2013. Critical role of segment-specific packaging signals in genetic reassortment of influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E3840–E3848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308649110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White MC, Steel J, Lowen AC. 2017. Heterologous packaging signals on segment 4, but not segment 6 or segment 8, limit influenza A virus reassortment. J Virol 91:e00195-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00195-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cobbin JC, Ong C, Verity E, Gilbertson BP, Rockman SP, Brown LE. 2014. Influenza virus PB1 and neuraminidase gene segments can cosegregate during vaccine reassortment driven by interactions in the PB1 coding region. J Virol 88:8971–8980. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01022-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitnaul LJ, Matrosovich MN, Castrucci MR, Tuzikov AB, Bovin NV, Kobasa D, Kawaoka Y. 2000. Balanced hemagglutinin and neuraminidase activities are critical for efficient replication of influenza A virus. J Virol 74:6015–6020. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.13.6015-6020.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner R, Matrosovich M, Klenk HD. 2002. Functional balance between haemagglutinin and neuraminidase in influenza virus infections. Rev Med Virol 12:159–166. doi: 10.1002/rmv.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaverin NV, Gambaryan AS, Bovin NV, Rudneva IA, Shilov AA, Khodova OM, Varich NL, Sinitsin BV, Makarova NV, Kropotkina EA. 1998. Postreassortment changes in influenza A virus hemagglutinin restoring HA-NA functional match. Virology 244:315–321. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gottschalk A. 1958. The influenza virus neuraminidase. Nature 181:377–378. doi: 10.1038/181377a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gen F, Yamada S, Kato K, Akashi H, Kawaoka Y, Horimoto T. 2013. Attenuation of an influenza A virus due to alteration of its hemagglutinin-neuraminidase functional balance in mice. Arch Virol 158:1003–1011. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1577-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li C, Hatta M, Watanabe S, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. 2008. Compatibility among polymerase subunit proteins is a restricting factor in reassortment between equine H7N7 and human H3N2 influenza viruses. J Virol 82:11880–11888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01445-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hara K, Nakazono Y, Kashiwagi T, Hamada N, Watanabe H. 2013. Co-incorporation of the PB2 and PA polymerase subunits from human H3N2 influenza virus is a critical determinant of the replication of reassortant ribonucleoprotein complexes. J Gen Virol 94:2406–2416. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.053959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Octaviani CP, Goto H, Kawaoka Y. 2011. Reassortment between seasonal H1N1 and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza viruses is restricted by limited compatibility among polymerase subunits. J Virol 85:8449–8452. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05054-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]