Abstract

For over a decade since the release of the Institute of Medicine report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, there has been a focus on providing coordinated, comprehensive care for cancer survivors that emphasized the role of primary care. Several models of care have been described which primarily focused on primary care providers (PCPs) as receivers of cancer survivors and specific types of information (e.g. survivorship care plans) from oncology based care, and not as active members of the cancer survivorship team. In this paper, we reviewed survivorship models that have been described in the literature, and specifically focused on strategies aiming to integrate primary care providers in caring for cancer survivors across different settings. We offer insights differentiating primary care providers’ level of expertise in cancer survivorship and how such expertise may be utilized. We provide recommendations for education, clinical practice, research and policy initiatives that may advance the integration of primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors in diverse clinical settings.

INTRODUCTION

A decade ago the Institute of Medicine report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition was released recommending coordinated, comprehensive care for cancer survivors and emphasizing the involvement of primary care.(1) Historically, primary care providers’ role across the cancer care continuum has predominately focused on prevention and early detection. (2) There are an estimated 15.5 million cancer survivors in the U.S., most of whom are five years or more beyond active treatment and are largely represented by older adults.(3–5) (Box 1) As this population continues to grow, strategies to integrate primary care into long-term care must also evolve.

Box 1. Cancer Survivorship by the Numbers.

Survivorship in the United States

-

15.5 million living with history of cancer as of Jan 1, 2016

The top 3 cancers in men (prostate, colorectal, melanoma) and women (breast, uterine, colorectal) account for over 60% of all survivors

Nearly half of the survivor population are 70+ years old

Pediatric cancer survivors <1% of the total survivor population

Close to 70% of survivors are 5 years out from treatment; 44% have survived 10 years or more; 20% have survived 20 years or more

Survivorship Around the Globe

14.1 million new cancer cases diagnosed in 2012

32.6 million survivors five-years post treatment (as of 2012)

Source: Miller et al. 2016

Ongoing and emerging trends in health care further drive the need for more extensive primary care integration in cancer survivorship care. These include: (1) growing demands for acute cancer care by oncology providers as more new primary diagnoses emerge in an aging population; (6) (2) greater numbers of long-term, older cancer survivors, many in need of follow-up care and management of late- and long-term effects due to cancer and/or cancer treatment; (4) (3) multi-morbidities among both the newly diagnosed and surviving population requiring shared management; (7, 8) (4) an emphasis on behaviors necessary to engage in self-management and lifestyle modifications to optimize health; (9) and (5) changing reimbursement for medical care, specifically in the United States. (10)

Much of the literature published to date has focused on the assessment of primary care providers’ capacity to care for the growing population of cancer survivors. (11–16) Research suggests that PCPs’ knowledge of cancer survivorship care is suboptimal. (17–19) While many PCPs prefer caring for survivors (20), primary care providers consistently report the need for more training in cancer survivorship. (21, 22) McCabe and Oeffinger proposed a shared care model which described the need for risk stratification strategies to differentiate which cancer survivors would be optimally transitioned into oncology-based, primary care based or shared care long-term care models.(23) Such risk-stratification approaches have been endorsed as an essential element to high quality follow-up care;(24) however, there remains a lack of evidence to support the effectiveness of the models that may best suit specific (e.g., high, moderate, low risk) subsets of cancer survivors.(25) A recent systematic review concluded that there is currently no standard of care among models of cancer survivorship care and that they vary widely by context based on the type of provider (physician or nurse) leading the care, whether a survivorship care plan is a key intervention feature of the model, and whether the model includes group or individual counseling. (26, 27) This review also found limited evidence regarding the potential benefits of the models and their effects on outcomes. (26, 27)

We reviewed cancer survivorship models that have been described in literature, specifically focusing on those aiming to integrate primary care providers in caring for cancer survivors in different settings. Based on our findings, we offer insights for future opportunities in education, clinical practice, research and policy initiatives that may enhance the role of primary care providers in cancer survivorship care.

SEARCH STRATEGY AND SELECTION CRITERIA

We used a scoping review methodology (28, 29) that includes both narrative review and evidence mapping approach that is appropriate for use when a field is nascent, not yet well defined and has limited evidence to support a systematic review. We identified previously described models of cancer survivorship care that specifically addressed the role of primary care providers. Based on this literature, we outlined specific strategies that would actively engage primary care providers in cancer survivorship care. To identify supporting evidence, we searched the PubMed database which is comprised of more than 24 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed). Terms used to generate articles for analysis in the searches were “primary care and cancer survivorship,” “general practitioner and cancer survivorship,” “family practice and cancer survivorship,” and “care model and cancer survivorship.” The search was conducted in July 2016. We used Endnote X7 reference software to conduct searches and manage references and the article database. Timeframe for the search was not limited. A total of 119 articles were identified in the initial searches. All references and abstracts were downloaded into the Endnote X7 reference software library by two undergraduate research interns. All potentially eligible study abstracts were reviewed by SVH and DO. All abstracts were reviewed by the two coders for relevance and fit. Primary inclusion criteria were that manuscripts report original research or use empirical examples to describe models with an integrative role for primary care. Disagreements in classification of the articles were discussed and resolved by the authors (LN, SH and DO). Using the groups feature in EndnoteX7, references were classified and coded as irrelevant if they: (1) were commentaries, (2) were solely model development or medical education focused or (3) did not provide description of primary care settings or practices related to survivorship care.

OVERVIEW OF MODELS OF CARE

A total of 14 articles (18, 19, 23, 27, 30–40) fit the inclusion criteria. To supplement the models described in literature, we accessed related survivorship models of care proposed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) (https://www.asco.org/practice-guidelines/cancer-care-initiatives/prevention-survivorship/survivorship/survivorship-compendium).

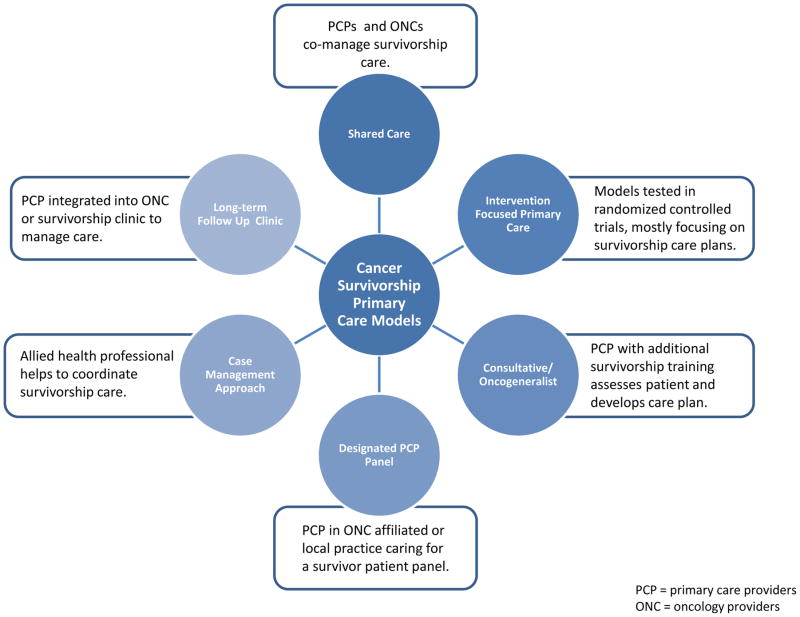

Four articles and the ASCO website describe conceptual models that include primary care integration. (19, 23, 35, 42) Oeffinger and McCabe (23) discussed the shared care model describing a risk based stratification process, an adapted strategy from models that had been applied in pediatric cancer survivor population with the additions of a communication strategies between oncologists and primary care clinicians throughout the cancer care experience. McCabe et al. (35) further described a lack of research to inform the implementation and testing of risk-stratified care approaches. Grunfeld and Earle (41) outlined challenges of coordinating care and communicating during the post-treatment phase describing the potential for survivorship care plans as a facilitative tool. Nekhlyudov (19) proposed that a trained oncogeneralist - a primary care provider who can “define and integrate the complex needs of adult cancer survivors” (44) - be involved in survivorship care. Specifically, the four models for integrating primary care providers included: (1) an oncogeneralist offering comprehensive and continuous care in a cancer center; (2) an oncogeneralist offering consultative care in a cancer center; (3) designated primary care at affiliated and/or local practices; and, (4) designated primary care provided by academic or community-based primary care providers. The ASCO website describes several additional models of cancer survivorship care, some of which include primary care involvement. These include: oncology specialist models, multi-disciplinary clinics, treatment/disease site specific clinics, general survivorship clinics, consultative survivorship clinics, integrated survivorship clinics, community generalist models and shared care models (with and without transitions). Further, we found published literature describing cancer survivorship care within primary care settings and among primary care providers including examples of the following: shared care (40, 42), interventions comparing primary care survivorship delivery to a specialist arm (18, 33, 34), consultative or oncogeneralist model, (37, 39), designated primary care panel within primary care settings (37) and case management approach (31, 37). Finally, one example of a primary care physician-led survivorship clinic specializing in long-term follow-up was described (37). Some of the models offered care to survivors of adult cancers, while others were restricted to adult survivors of childhood cancers.

While there were a number of proposed models of care (Figure 1), we found limited evidence for the models described. Overall, cancer survivorship models have focused on the provision of survivorship care plans and the integration of PCPs into cancer care teams to manage the late- and long-term effects; however, other models of cancer survivorship care that further integrate primary care providers into cancer survivorship within primary care settings do exist and are in need of further development and evaluation. Despite growing interest in cancer survivorship care and the evolving role of the primary care provider, description and evaluation of different models of care are limited.

Figure 1. Models of Care.

PCP = primary care providers

ONC = oncology providers

FUTURE OPPORTUNITIES

The gaps in the literature and in the types of primary care models evident present a number of opportunities for exploring ways to enhance primary care of cancer survivors. In the following section, we offer insights into opportunities for future changes in education, clinical practice, research and policy that may enhance the role of primary care providers in cancer survivorship care.

Education and Training

As the number of cancer survivors continues to grow and most will receive their care in community based settings, it is critical that all primary care providers have the basic core competencies including understanding about the epidemiology of cancer survivorship, surveillance for cancer recurrences, screening and management of long-term and late effects of cancer, psychosocial concerns of cancer survivors and health promotion (43) (Table 1). Such competencies are akin to others primary care providers must possess to care for patients with other chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes, congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive lung disease. Medical education and training of residents and practicing clinicians about the issues in cancer survivorship care is needed. The advantage to early training is that the student obtains a foundational framework for cancer survivorship as a field, which allows for ease of learning subsequent information and absorbing of updates in clinical recommendations. To date, few education resources are available through online programs, emerging medical school and residency currricula as well as continuing medical education programs (Box 2).

Table 1.

Core Comptencies for Cancer Survivorship – American Society of Clinical Oncology

| Topic | Core Competencies |

|---|---|

| Survivorship |

|

| Surveillance |

|

| Long term and Late effects |

|

| Health Promotion and Disease Prevention |

|

| Psychosocial Care |

|

| Childhood and Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors |

|

| Older Adult Cancer Survivors |

|

| Caregivers of Cancer Survivors |

|

| Communication and Coordination of Care |

|

Reprinted with permission from Shapiro, C.L., et al., ReCAP: ASCO Core Curriculum for Cancer Survivorship Education. Journal of Oncology Practice, 2016: p. JOPR009449.

Box 2. Examples of Cancer Survivorship Education and Training Resources for Primary Care Providers.

American Society of Clinical Oncology

Online educational programs on a variety of topics related to cancer. Several programs in cancer survivorship are available.

Focus Under Forty, a program specifically targeting primary care providers’ awareness of cancers affecting adolescents and young adults. Available free of charge to primary care providers.

http://www.university.asco.org/focusunder40#PrimaryCareRole

Survivorship Care Compendium – a resource developed to serve as a repository of tools and resources to enable oncology providers to implement or improve survivorship care within their practices. Also with useful information for the primary care providers.

http://www.asco.org/practice-research/asco-cancer-survivorship-compendium

Cancer Survivorship Symposium: Advancing Care and Research: A Primary Care and Oncology Collaboration

A collaboration among the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology provides information about survivorship issues for primary care physicians and oncologists.

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

Videos intended for patients that may be helpful and informative for the primary care provider.

http://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/survivorship/videos-survivors

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center/City of Hope: R25 Preparing Professional Nurses for Survivorship Care (Training Grant)

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Links to videos on a variety of topics in cancer survivorship, some geared toward patients, but very relevant to the primary care provider.

http://www.dana-farber.org/newsroom/videos.aspx?tag=Survivorship

http://www.dana-farber.org/For-Adult-Cancer-Survivors/Experts-Speak-on-Survivorship-Topics.aspx

Dana Farber/Harvard Medical School Continuing Medical Education Program, “Optimizing Care and Outcomes”

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Links to educational programs taught by faculty on topics including overview, psychosocial issues, physical symptoms, among others.

The National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center

A George Washington University Cancer Institute program developed in collaboration with the American Cancer Society and the CDC.

Addressing Cancer Survivors’ Needs After Treatment: An Introduction

This 45-minute, pre-recorded training webinar (initally targeting navigators) offers information on the top issues cancer survivors face after completing treatment and a discussion of resources that may be used to assist survivors transitioning from active treatment.

The Cancer Survivorship E-Learning Series is a free continuing education program that provides a forum to educate primary care providers to better understand and care for survivors in the primary care setting. Several modules have been released, others are in development.

UpToDate®

An evidence-based resource aimed at helping clinicians make decisions in clinical practice. Now includes a section on cancer survivorship, with an expanding topic reviews.

Requires a subscription, often available at local hospitals and libraries.

http://www.uptodate.com/contents/search?search=cancer+survivorship&;x=0&y=0

Education and training of a subset of primary care physicians can be expanded beyond the cancer survivorship core competencies; for example, primary care physicians may receive additional expertise in cancer related care (oncogeneralist model) (44). Such training may occur via participation in specialized programs, (45) continuing medical education conferences and workshops, or internship-like “shadowing” in institutions caring for cancer survivors. Such providers would be leading the field and help address the knowledge gaps that have been identified among PCPs, help bolster patient and oncology provider receptivity to transitioning to primary care, and also increase the capacity of primary care systems infrastructure to develop collaborative care. Models for such specialization (without certification) currently exist in other chronic conditions, such as HIV where patients may benefit from more specialized primary care (46). Experts in cancer survivorship may be engaged in teaching medical students, residents, fellows and practicing providers. They can also help to synthesize the information in oncology literature and make it “digestible” for practicing primary care providers. Certification in a sub-specialty of cancer survivorship may also be considered.(44)

Our review and prior studies found examples of oncogeneralists who serve as members of a cancer survivorship program at a cancer facility, a general medicine clinic or community practice in oncology or primary care, caring for survivors in programs focusing on adult cancers, others in long-term pediatric cancer survivorship programs. (37, 39, 47). (Figure 1 and Box 3) Depending on the setting, the oncogeneralist may be involved in collecting information about the patient’s prior cancer type and treatment, and develop a strategy for assessing risk of recurrence as well as management and surveillance for late and long-term effects in the context of their other comorbid medical conditions. Further, depending on the setting, the oncogeneralist may develop a survivorship care plan that is individualized to the patient needs, particularly weighing in on the interplay between cancer-related and comorbid medical conditions and their treatments.(39) In our recent study describing early innovators of primary care-centric models, each of the four primary care physicians who were key informants worked in an oncogeneralist model. (37) In one case, the providers delivered continuity of care for long-term survivors (37). However, as previously noted, there have been limited (if any) evaluations of such programs.

Box 3. Examples of existing programs with generalist involvement in cancer survivorship in the United States.

Cancer Centers

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute

Dana Farber Cancer Institute

MD Anderson Cancer Institute

Massachusetts General Hospital

Breast Cancer Survivorship Program at Johns Hopkins

Academic Centers General Internal Medicine

University of Colorado

University of Pennsylvania

Community Based Oncology Settings

Redwood Regional Medical Group

Community Based Primary Care Settings

Springfield Medical Associates

Development of Clinical Practice Guidelines

The Children’s Oncology Group has been at the forefront of developing guidelines targeting the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer.(48) However, these guidelines, along with others developed by organizations such as the American Cancer Society and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network have traditionally focused on oncology settings (49–52). While these guidelines are now incorporating a growing evidence base (much of which is still lacking for survivors of adult cancers), the guidelines may be too complicated and not readily accessible by primary care providers. Recent progress is being made to develop survivorship guidelines targeting primary care providers. To date, the American Cancer Society has released guidelines for primary care providing recommendations for the follow up of survivors of colorectal (53), breast (54), prostate (55), and head and neck (56) cancers. These primary care-focused cancer survivorship guidelines offer helpful and thorough information for primary care providers where it was previously lacking; however, many recommendations lack strong evidence base and it remains unclear which care needs should be prioritized. Controversial recommendations, often due to incomplete evidence, are not unusual in guideline development. Some have adopted strategies to enhance cross-discipline discourse to enhance guideline development and the likelihood for adoption. For example, the current process employed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force includes release of draft guidelines for public review and comment. Since translation of survivorship guidelines will occur in primary care, it would be optimal for primary care providers to vet recommendations that are made by experts to assess for the feasibility and applicability in their settings.

Further, guidelines are only one tool that could support primary care providers in the delivery of survivorship care. Clinical assessment guidance and prioritization are essential for translation potential. Specifically, in addition to cancer-related care, it is important to incorporate comorbid medical conditions, functional status and age into recommended follow up survivorship care (http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/decision/mcc/index.html). Recommendations must be practical and disseminated in the channels that are visible to primary care providers. Lastly, as has been successfully implemented by the childhood oncology groups, harmonization of guidelines across different organizations and countries is needed.

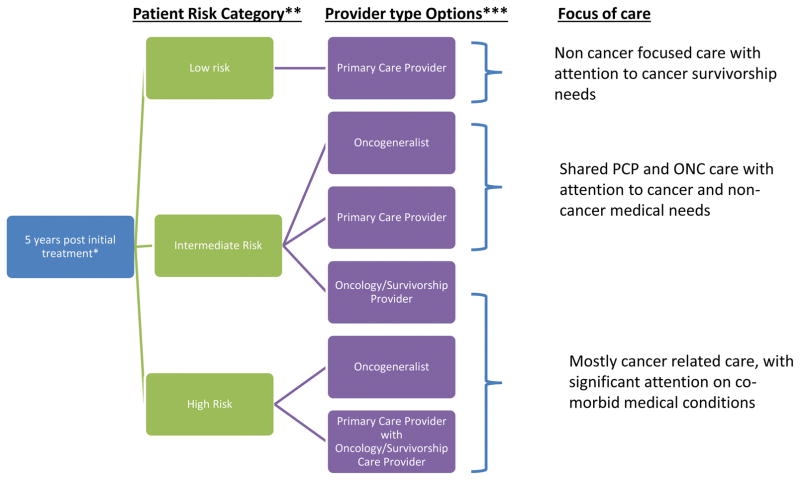

Risk Stratification to Guide Clinical Care

Prior publications have proposed a risk stratification approach to cancer survivorship care (35) as a means of defining the optimal setting for follow up of cancer survivors in mostly oncology, shared care or mostly primary care models. This model is similar to that described by the UK National Cancer Survivorship Initiative (http://www.ncsi.org.uk/what-we-are-doing/risk-stratified-pathways-of-care/risk-stratification/). We propose that risk stratification may further define the level of primary care involvement and consider non-cancer care in the decision making regarding delineation of care. (FIGURE 2) For example, patients with common diagnoses (i.e. breast, colorectal, prostate cancers), early stage disease, standard treatment, elderly and those with non-cancer comorbid medical conditions, may be transitioned to community based primary care providers.

Figure 2. Survivorship Care Strategies.

Notes:

*5 years is based on general recommendations in the cancer community, transition of care may vary

- Low risk common cancers (i.e. breast, colorectal, prostate), early stage, standard treatment, high non-cancer chronic condition burden.

- Intermediate less common cancers, advanced stages, multimodal treatment, moderate non-cancer chronic condition burden.

- High risk rare cancers, advanced stages, complex medical treatment with significant late/long term effects.

***Any of these models may be appropriate for NP/PA involvement.

To help the transition, oncology providers should engage primary care providers in the care of patients during cancer treatment. By communicating with the treatment team during this phase of care, PCPs may be able to offer input regarding non-cancer care and become familiar with issues that may have occurred during treatment and thus avoid the potential “loss in transition” to primary care-led follow up. Further, communication may build interpersonal relationship among the team members that may promote future collaboration and trust. Oncology providers are also encouraged to reach out to PCPs to provide education and guidance about cancer-related surveillance and management. Such outreach may occur individually via consultation letters or survivorship care plans or via informal group teaching in in-person or web-based seminars.

Patients with less common adult or childhood-onset cancers, late stage cancers, and/or cancers treated with multimodal therapies who may have experienced late effects or comorbid medical conditions may be transitioned to oncogeneralists in the community or to designated PCPs who may have expressed an interest in caring for cancer survivors. For example, a cancer facility may identify PCPs in academic or community based practices who have expressed an interest (without specified expertise) in caring for survivors. These providers may be practicing in settings that are formally affiliated with the cancer center, or those in the surrounding communities. Unlike the oncogeneralists, these providers would not have formal expertise in cancer survivorship, but may have had some education in this area. Patients may feel more comfortable in selecting PCPs who are recommended to them by their oncology providers as having an interest in survivorship and may be more willing to transition their care. A survivorship care plan (or any tool that serves as a vehicle for information sharing) should be developed by the oncology team and revisited during follow up to assure that “shared” care is optimally coordinated until it is deemed appropriate to transition to the PCP. Case managers may be able to assist in care coordination in such scenarios (31, 37).

Patients with rare cancers of adulthood or those diagnosed in childhood, or those treated with complicated regimens (i.e. bone marrow transplant), and who have existing or significant risk for late and long-term effects may be optimally followed in survivorship clinics, staffed by oncogeneralists or oncology providers. Oncogeneralists may be able to offer a holistic perspective on the care of these patients, balancing the competing demands of comorbid disease management. A primary care provider for such patients is nevertheless recommended for preventive and non-cancer related care. As these patients will have multi-specialty follow up, coordination of care will be critical.

For each of the models, in order for transitions of care or shared care to be effective, there must be clear pathways for communication between oncology and PCPs. Early training in communication and collaborative care is needed. As no single method is most effective, preferred or possible (for example, due to geographic, financial, insurance coverage limitations and/or preferences), aiming for perfect communication should not be allowed to impede all communication. We encourage consideration of electronic health records, e-mails, paper documentation, phone calls, in person meetings, virtual meetings, tumor boards, survivorship care plans (that may also be stored in “clouds”), among others. Such communication enhances inter-professional trust, coordination of care and avoidance of omitted or duplicated care.

Clinical Workforce

The shortage of primary care physicians (57) and oncology providers (58) in the U.S. may pose a particular challenge to transitioning cancer survivors to primary care settings. As such, nurse practitioners and physician assistants may be brought in to work closely with primary care physicians in the care of these patients. This model has been embraced by many cancer centers and oncology practices. While primary care practices are now encouraged to work with non-physician providers for management of comorbid medical conditions, such as diabetes or congestive heart failure, these professionals may also be employed to help manage long-term cancer survivors. For example, in our recent study (37), one provider used a collaborative model with a nurse practitioner who conducted routine physical examinations with survivors (providing preventive care such as breast examinations and Pap smears, as well as lifestyle counseling). The patients were then scheduled for a follow up visit with the PCP to address specific survivorship related issues. Educational programs and training, as outlined above for the physicians, may also be offered (and evaluated) to expand the knowledge of the allied health professional workforce.

Payment Incentives and Practice Redesign

Further research and policy initiatives should explore whether offering incentives to primary care providers who take on the care of cancer survivors and offer them comprehensive, coordinated care are impactful in enhancing survivorship care in primary care settings. Such incentives are now utilized for the care of high priority conditions in primary care such as diabetes, hypertension and coronary artery, where metrics are reported and may impact payment. To date, no recommended metrics or measurable outcomes exist for survivorship care that can inform discussions of survivorship quality of care in a primary care context. While the ASCO Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) have begun to develop quality measures of survivorship, these focus primarily of provision of care outside the realm of primary care (59). Future efforts that aim to identify which sub-populations of cancer survivors may be appropriately considered a “target population” in primary care is needed. For example, in the United States, there has been an evolving interest in patient-centered medical care that emphasizes care that is coordinated, comprehensive, timely, high quality and safe. The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model has been tested in a variety of settings and has been found to improve health outcomes, patient and provider satisfaction and costs. (60) There are a number of components of the PCMH that can and should be implemented for cancer survivors such as identifying and managing cancer survivors at the population level within health care settings, providing care management, tracking, and coordinating their care. However, many of these strategies have yet to be implemented in a comprehensive or systematic fashion, leaving cancer survivors largely responsible for coordinating their own care as they transition between primary care and oncology. There are some who advocate for primary care versus oncology PCMHs. However, there are no data on the viability of oncology PCMHs or whether primary care PCMHs attend to cancer survivors as a population in need of care coordination and management. Over the upcoming years, practices across the United States will be selected by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service to test the effect of this model on outcomes of cancer patients and survivors. These demonstration projects have the potential to improve the care of survivors by offering timely, necessary and non-duplicative care, improving management of chronic disease and addressing psychosocial concerns.

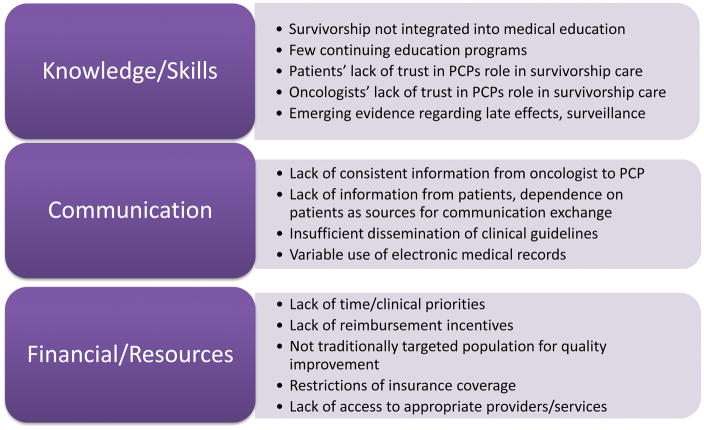

Expand Evidence-Base in Cancer Survivorship Care

There are significant barriers remaining in integrating primary care providers in cancer survivorship care (Figure 3) and gaps in research based evidence to date. As alluded to in prior sections, future research should focus on models of care in different settings addressing the role of primary care providers in such models, how risk stratification to guide care settings and intensity of follow up may assist in guiding care for survivors, as well as methods to incentivize quality of care and how quality may be measured. It is important to evaluate the design and implementation of cancer survivorship care across diverse settings, taking into account the populations being served and the available resources. Intervention and descriptive studies that examine the complexity of health and health systems interventions are needed. Studies of barriers and incentives of the implementation of primary care guidelines for survivorship care are necessary. In addition, studies that consider and characterize the multi-level context and environment where primary care providers practice and that are attentive to the importance of understanding and assessing resources expended, programs costs, cost-effectiveness and the impact of other economic outcomes will be necessary. As previously described by Halpern, (27) how models are evolving in practice are highly influenced by the context in which they are developed. Efforts to develop primary care strategies for cancer survivorship care attending to the importance of context in the process of primary care will be essential. While focusing on survivorship in research initiatives adds important emphasis on this phase of care, from the primary care perspective, it may be optimal to consider this solely a phase along the cancer continuum. Specifically, studies may be designed to understand the roles that primary care providers have (or may undertake) across cancer care from prevention, screening, active treatment, survivorship, palliation and end of life care.

Figure 3.

Examples of Barriers to Primary Care Integration in Cancer Survivorship

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we found that while different models to involve primary care in cancer survivorship care exist, few such models have been fully described or tested. It is quite likely that one model will not fit all. Oncogeneralists may serve as experts in the care of cancer survivors in cancer centers, academic medical centers or community and in addition to providing clinical care, may be vehicles for education among peers and oncology providers. Primary care providers with no advanced training, however, may be readily involved in the care of survivors in a variety of settings, specifically caring for survivors who may be at a lower risk of cancer-related complications. All primary care providers however, should be primed to care for this growing population of patients and have the basic core competencies to do so. Communication with oncology providers must start early in training and continue through years in practice. Research and policy must continue to evolve as there is a critical need for evidence-based guidelines, implementation and evaluation of quality of care.

Acknowledgments

Ms. O’Malley was supported through a Doctoral Training Grant in Oncology Social Work (DSW 13-279-01) from the American Cancer Society. Dr. Hudson was partially supported by grants R01CA176838 and R01CA176545 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS: All authors participated in developing the design and data analysis plan, interpretation and writing of the manuscript. Ms. O’Malley conducted the initial literature search, results of which were reviewed by Drs. Nekhlyudov and Hudson.

References

- 1.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, et al. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2489–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016 doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer Survivors in the United States: Prevalence across the Survivorship Trajectory and Implications for Care. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2013;22(4):561–70. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer survivors: a booming population. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20(10):1996–2005. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, et al. Future supply and demand for oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2007;3(2):79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards BK, Noone AM, Mariotto AB, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(9):1290–314. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leach CR, Weaver KE, Aziz NM, et al. The complex health profile of long-term cancer survivors: prevalence and predictors of comorbid conditions. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2015;9(2):239–51. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61(1):50–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnipper LE, Meropol NJ. Payment for cancer care: time for a new prescription. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4027–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friese CR, Martinez KA, Abrahamse P, et al. Providers of follow-up care in a population-based sample of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(1):179–84. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2851-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101(8):1712–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chubak J, Tuzzio L, Hsu C, et al. Providing care for cancer survivors in integrated health care delivery systems: practices, challenges, and research opportunities. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(3):184–9. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, et al. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2270–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenison TC, Silverman P, Sustin M, et al. Differences between nurse practitioner and physician care providers on rates of secondary cancer screening and discussion of lifestyle changes among breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):223–9. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0405-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luctkar-Flude M, Aiken A, McColl MA, et al. Are primary care providers implementing evidence-based care for breast cancer survivors? Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(11):978–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suh E, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski K, et al. General internists’ preferences and knowledge about the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Annals of internal medicine. 2014;160(1):11–7. doi: 10.7326/M13-1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, et al. Evaluating survivorship care plans: results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(36):4755–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nekhlyudov L. Integrating primary care in cancer survivorship programs: models of care for a growing patient population. Oncologist. 2014;19(6):579–82. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, et al. Primary care physicians’ views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. Journal of clinical oncology. 2009;27(20):3338–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, et al. Caring for cancer survivors: a survey of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4409–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virgo KS, Lerro CC, Klabunde CN, et al. Barriers to breast and colorectal cancer survivorship care: perceptions of primary care physicians and medical oncologists in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(18):2322–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(32):5117–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(5):631–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell D, Hack T, Oliver T, et al. Models of care for post-treatment follow-up of adult cancer survivors: a systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2012;6(4):359–71. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0232-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(6):345–51. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halpern MT, Viswanathan M, Evans TS, et al. Models of Cancer Survivorship Care: Overview and Summary of Current Evidence. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2015;11(1):e19–e27. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pham MT, Rajic A, Greig JD, et al. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson EK, Rose PW, Loftus R, et al. Cancer survivorship: the impact on primary care. British Journal of General Practice. 2011;61(592):e763–e5. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X606771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sussman J, McBride ML, Sisler J, et al., editors. Integrating primary care and cancer care in survivorship: A collaborative approach. ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howell D, Hack TF, Oliver TK, et al. Models of care for post-treatment follow-up of adult cancer survivors: a systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(4):359–71. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0232-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wattchow DA, Weller DP, Esterman A, et al. General practice vs surgical-based follow-up for patients with colon cancer: randomised controlled trial. British journal of cancer. 2006;94(8):1116–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, et al. Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: a comparison of family physician versus specialist care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(6):848–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCabe MS, Partridge AH, Grunfeld E, et al. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;40(6):804–12. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sussman J, Souter E, Grunfeld E, et al. Models of cancer survivorship. Toronto (ON): Cancer Care Ontario; 2012. Program in Evidence-based Care Evidence Base Series No-26. [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Malley D, Hudson SV, Nekhlyudov L, et al. Learning the landscape: implementation challenges of primary care innovators around cancer survivorship care. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2016:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0555-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viswanathan M, Halpern M, Swinson Evans T, et al. Models of Cancer Survivorship Care. Rockville MD: 2014. Mar, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Overholser LS, Moss KM, Kilbourn K, et al. Development of a Primary Care-Based Clinic to Support Adults With a History of Childhood Cancer: The Tactic Clinic. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2015;30(5):724–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hahn EE, Ganz PA. Survivorship Programs and Care Plans in Practice: Variations on a Theme. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2011;7(2):70–5. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grunfeld E, Earle CC. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: treatment through survivorship. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2010;2010(40):25. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jefford M, Kinnane N, Howell P, et al. Implementing novel models of posttreatment care for cancer survivors: Enablers, challenges and recommendations. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2015;11(4):319–27. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shapiro CL, Jacobsen PB, Henderson T, et al. ReCAP: ASCO Core Curriculum for Cancer Survivorship Education. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009449. JOPR009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong S, Nekhlyudov L, Didwania A, et al. Cancer survivorship care: exploring the role of the general internist. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S495–500. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant M, Economou D, Ferrell B, et al. Facilitating survivorship program development for health care providers and administrators. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):180–7. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0397-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chu C, Selwyn PA. An Epidemic in Evolution: The Need for New Models of HIV Care in the Chronic Disease Era. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(3):556–66. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9552-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell MK, Tessaro I, Gellin M, et al. Adult cancer survivorship care: experiences from the LIVESTRONG centers of excellence network. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(3):271–82. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0180-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Children’s Oncology Group. [Last accessed on August 14, 2016];Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers. 2014 Version 4-October 2013:[Available from: http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/

- 49.Khatcheressian JL, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Breast cancer follow-up and management after primary treatment: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(7):961–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyerhardt JA, Mangu PB, Flynn PJ, et al. Follow-up care, surveillance protocol, and secondary prevention measures for survivors of colorectal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(35):4465–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.7442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohler JL. The 2010 NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology on prostate cancer. Journal of the national comprehensive cancer network. 2010;8(2):145. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ligibel JA, Denlinger CS. New NCCN guidelines® for survivorship care. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2013;11(5S):640–4. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Penson DF. Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Guidelines: American Society of Clinical Oncology Practice Guideline Endorsement. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.004606. JOP. 2015.004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66(1):43–73. doi: 10.3322/caac.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skolarus TA, Wolf A, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014;64(4):225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen EE, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66(3):203–39. doi: 10.3322/caac.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, et al. Projecting US Primary Care Physician Workforce Needs: 2010–2025. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10(6):503–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shulman LN, Jacobs LA, Greenfield S, et al. Cancer care and cancer survivorship care in the United States: will we be able to care for these patients in the future? J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(3):119–23. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0932001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mayer DK, Shapiro CL, Jacobson P, et al., editors. Assuring Quality Cancer Survivorship Care: We’ve Only Just Begun. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book/ASCO American Society of Clinical Oncology Meeting; 2014; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nelson M, Buelt L, Patel K, et al. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. The Patient-Centered Medical Home’s Impact on Cost and Quality. Annual Review of Evidence 2014–2015. May be accessed at https://www.pcpcc.org.