Abstract

It is well known that parental and community-based support are each related to healthy development in LGBTQ youth, but little research has explored the ways these contexts interact and overlap. Through go-along interviews (a method in which participants guide the interviewer around the community) with 66 youth in British Columbia, Massachusetts, and Minnesota, adolescents (aged 14–19 years) reported varying extent of overlap between their LGBTQ experiences and their parent-youth experiences; parents and youth each contributed to the extent of overlap. Youth who reported high overlap reported little need for resources outside their families but found resources easy to access if wanted. Youth who reported little overlap found it difficult to access resources. Findings suggest that in both research and practice, considering the extent to which youth feel they can express their authentic identity in multiple contexts may be more useful than simply evaluating parental acceptance or access to resources.

Keywords: LGBTQ, youth, adolescents, parenting, parent-child relations, family

Societal acceptance for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning (LGBTQ) individuals has been steadily increasing in North America, yet unique challenges between parents and LGBTQ youth still occur because of stigma (Rosario et al., 2014a; Rosario et al., 2014b; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Parental and family relationships do not exist in isolation from other developmental contexts such as schools (Carrasquillo & London, 2013) and peers (Shilo & Savaya, 2011). Some research has attempted to quantify the relative importance of parents, teachers, classmates, and friends as sources of social support for LGBTQ youth (Watson, Grossman, & Russell, 2016a). Comparing these four sources of support, having supportive parents was most strongly related to lower depression and higher self-esteem in LGBTQ youth compared to having parents that were less supportive (for friends and family, see Shilo & Savaya, 2011; for all four sources, see Watson et al., 2016a). To date, however, most research with families of LGBTQ youth has focused on studying the dynamics of parent-child relationships without considering the larger community contexts in which youth live. In this paper, we sought to understand how youth describe and experience the intersection of their relationships with their parents and their experiences being LGBTQ in the community. To achieve our aims, we analyzed all quotes related to family from a broader qualitative, multi-site study of LGBTQ adolescents and their environments.

Family and Parent Support for LGBTQ Youth

An emerging body of literature has documented the importance of family – particularly parents – for the emotional well-being of LGBTQ youth (Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010; Shilo & Savaya, 2011). Family support has been found to be important in various sub-groups of youth (e.g., gay, bisexual, lesbian, males and females) but is related to distress, depression, and self-esteem in different ways for different sub-groups of youth (Shilo & Savaya, 2012; Watson et al., 2016a). Research has shown that positive parent relationships are protective for LGBTQ youth in ways that are unique when compared to heterosexual youth. For example, one study found an interaction between sexual orientation, general parent support, and school belonging. Specifically, same-sex attracted youth with low parental support reported less school belonging compared with heterosexual youth with low parent support. On the other hand, high parental support was associated with greater school belonging for same-sex attracted youth compared with hetrerosexuals (Watson, Barnett, & Russell, 2016b). This finding suggests that parental and school contexts may be especially interrelated for LGBTQ youth.

In addition to the importance of general parent support for the health of LGBTQ youth, LGBTQ-specific parental support and reactions are also important. LGBTQ-specific support has been shown to be related to mental health, self-esteem, social support, substance use, and general health status of LGBTQ youth (Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, & Malik, 2010; Rosario, Scrimshaw, & Hunter, 2009; Ryan et al., 2010). Family acceptance is related to these outcomes above and beyond the protections offered by community (e.g., LGBT events and bars) and friend support (Snapp, Watson, Russell, Diaz, & Ryan, 2015). Similarly, Rosario and colleagues’ (2009) found that it was the reaction to various disclosures from important individuals – no matter how many individuals the participants disclosed their sexual identity to – that most substantially predicted youth’s current and subsequent substance use.

Community Support for LGBTQ Youth

Beyond families, community support (such as neighborhoods, local LGBTQ organizations, and LGBTQ-related policies) is relevant for LGBTQ youths’ experiences and health (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, & Hasin, 2009). The research that explores community contexts finds that unsafe environments, and those less inclusive of LGBTQ individuals, are related to compromised mental health for LGBTQ individuals.

Scholars have focused on both self-reported and objective measures of the community context, such as self-reported neighborhood safety (Duncan & Hatzenbuehler, 2014), the proportion of registered Democrats and same-sex couples in a community (Hatzenbuehler, 2011), and LGB-specific college campus resources (Eisenberg & Wechsler, 2003). This research has found that youth living in unsafe (Duncan & Hatzenbuehler, 2014) or unsupportive (Hatzenbuehler, 2011) neighborhoods were more likely to report suicidal ideation than those in safer or supportive neighborhoods. Supportive environments in the form of LGB campus resources and policies are likewise related to positive outcomes such as less smoking for women (Eisenberg & Wechsler, 2003). In high-schools, having a Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) is related to an increased sense of safety (Fleming, 2012) and adolescents’ well-being (Poteat et al., 2012).

While there is clear evidence that families and communities are integral to the well-being of LGBTQ youth, less research has focused on how families of LGBTQ youth operate in broader contexts, such as the community. Perhaps due to the complexities of measuring the interrelated and reciprocal influences of multiple contexts, most extant research has considered the community context related to LGBTQ youth health separate from intersections with family.

Theoretical Framework

While the analysis conducted in this paper was inductive, the questions and chosen topic were guided by family systems theory (Whitchurch & Constantine, 1993) and a bioecological perspective of development (Bronfenbrenner, 2005; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). The larger study from which these data originated focused on understanding the relationships between environmental contexts and individual youth health outcomes. Family systems and bioecological perspectives suggest that youth and their interactions with their environments are not independent of their relationships within their family. In particular, the research questions addressed by this paper were guided by theoretical concepts at two levels. First, the importance of proximal processes (Bronfenbrenner, 2005), interdependence, and feedback (Whitchurch & Constantine, 1993) highlight the importance of looking at interactions within the family. At a broader level, the concepts of nested systems of context (Bronfenbrenner, 2005), and the hierarchy and boundaries of systems (Whitchurch & Constantine, 1993), highlight the importance of exploring the interactions between youth, family, and environment. By studying the ways LGBTQ youth, their parents, and their environments interact and influence one another, we gain insights into the complex relationships that impact the lives of LGBTQ youth.

Current Study

As noted, there is a need to understand how family and community contexts intersect to influence the health of LGBTQ youth. This paper was guided by three key questions. How do youth describe the interaction between their parents and the broader environment, if any? In what ways do youth see parents influencing their interaction with their broader environment and vice versa? How do youth indicate that parental acceptance (or rejection) impacts them when there are opportunities for other supports within the community? We explore these questions through go-along interviews with 66 LGBTQ youth in British Columbia, Massachusetts, and Minnesota.

Methods

Participants

This paper is part of a larger project focused on LGBTQ youth’s environments, resources, and healthy development (Porta et al., in press). We interviewed 66 adolescents aged 14–19 years who lived in twenty-four different cities [urban (n = 19), suburban (n = 22), and rural (n = 25)] across British Columbia (n = 23), Massachusetts (n = 19), and Minnesota (n = 24) between November 2014 and July 2015. Youth were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling through schools and LGBTQ youth-serving organizations and were diverse with regards to sexual orientation and gender (see Table 1). Half of the youth identified only White or European ancestry (n = 33), a quarter identified a mixed racial background (n = 14), and remaining participants identified Latino (n = 8), Asian (n = 4), Black or African (n = 3), Aboriginal or Native (n = 2), or other (n = 2) backgrounds.

Table 1.

Self-descriptors of sexual orientation and gender identity (n’s)

| Female | Male | Trans and additional labels^ | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gay or Lesbian` | 8 | 13 | 3 | 24 |

| Bisexual` | 8 | 10 | 3 | 21 |

| Queer and additional labels~ | 5 | 1 | 13 | 19 |

| Straight and other* | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 21 | 24 | 21 | 66 |

”gay or lesbian” includes n=2 “same-sex attraction;” “bisexual” includes n=1 “bicurious”

”trans” included n=11 whose self-descriptor included “trans” (e.g. “trans-female,” “non-binary trans person”; additional descriptors included n=10 who provided various labels, e.g. “genderqueer,” “fluid,” “non-binary” or “neutral”

n=9 “queer;” additional descriptors included n=7 “pansexual,” n=1 “asexual,” n=1 “panromantic asexual” and n=1 “rainbow sexual”

n=1 “straight” and n=1 “other”

In two locations, all participants consented for themselves. In Minnesota, minor-aged participants were asked if they were comfortable with interviewers gaining parental consent, as required by that University’s IRB; parental consent was waived for the one participant who was not comfortable with parental consent. Additional recruitment information is provided elsewhere (Porta et al., in press). Protocols were approved in each location by IRBs at the University of British Columbia, San Diego State University, and the University of Minnesota.

Interviews

Interviews were conducted using a go-along interview approach (Carpiano, 2009; Garcia, Eisenberg, Frerich, Letner & Lust, 2012; Porta et al., in press) in which participants guided interviewers to places they identified as safe and supportive. This method is particularly useful for this study of environments because moving through a participant’s community often elicits memories or comments that might not have been recalled sitting in a static location. The interview guide consisted of six open-ended questions about the youth’s environment (e.g., “If an LGBT friend came to visit you here in your town, where would you recommend they go to have fun or to hang out?” and “How does your community make you feel about being LGBT?”). In answering these open-ended questions, most youths (n = 59) discussed family members. Most (n = 36) participants guided the interviewer by foot or public transportation, others directed while the interviewer drove (n = 22), and the remaining (n = 8) participants remained in one location. Interviews lasted between 35 and 110 minutes (M = 78) and were recorded and professionally transcribed.

Analysis

Interview transcripts were uploaded to Atlas.ti to facilitate coding by a multi-site team. In the first round of coding, coders from each study location collaborated to create a codebook that consisted of mostly deductive codes based on the interview guide. Broad codes included locations (e.g., school, coffee shop, park), attributes (e.g., safe, unaccepting), people (e.g., family, teachers) and frequently mentioned experiences (e.g., coming out, bullying). All transcripts were independently coded by two coders and inconsistencies were reconciled through team discussion and clarification of code terms, definitions, and scope.

The present paper utilized the 397 quotes coded as relating to family. These quotes came from responses to primary or follow-up questions during interviews and were not particular to any single interview question. No specific question about family existed in the interview guide, however, of the 66 youths interviewed, 59 made at least one mention of family. Of all family members mentioned, parents were the subject of the vast majority of substantive quotes. All quotes related to parents were then analyzed using steps common to most thematic analysis. The quotes were open coded by the first author as a second level of coding (i.e., each sentence or segment was distilled or summarized with a word or brief phrase). Through axial coding - a process of organization based on similarity of concepts - the resulting open codes were then grouped into themes as the primary analytic step in the thematic analysis (Saldaña, 2009). The resulting themes were then checked against the original quotes about parents and family by re-reading transcripts and looking for quotes that were not captured by the themes. To ensure trustworthiness, each step of the coding process was shared and discussed in detail within regular meetings of the qualitative coding team, all of whom had extensive exposure to the full transcripts as well as access to family-specific codes.

Results

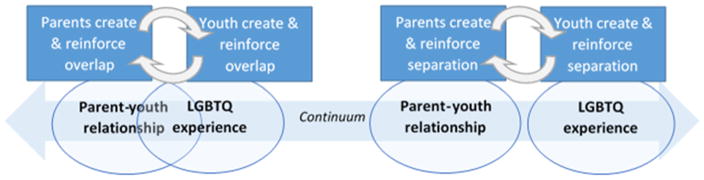

The overarching theme that arose was the varying extent to which adolescent’s experiences in their parent-youth relationships overlapped with (or remained separate from) their experience as an LGBTQ youth. (The latter refers to all activities, experiences, or expressions of self that are related to the youth’s LGBTQ identity.) To illustrate our findings, we conceptualized a continuum of overlap between parent-youth relationship experience and LGBTQ youth experience (Figure 1). On one end of the continuum are youths who experienced significant overlap between parent-youth relationships and their LGBTQ experiences; on the other end are youths for whom these two areas are distinct and separate.

Figure 1.

Reinforcement of overlap/separation between two experiences

We organized results by each end of the continuum; for each end, we illustrate the extent of overlap and then present the three sub-themes that emerged. In other words, each sub-theme is discussed twice, once to show the ways the sub-themes manifest when there is high overlap, and once to show the ways the sub-themes manifests when there is low overlap. The first sub-theme identified is that parents actively and passively contributed to the extent of overlap. Second, youths created and contributed to the extent of overlap. The contributions of parents and youths to the extent of overlap can be conceptualized as a feedback loop in which the actions of one build off of or are responsive to the actions of the other.

The third sub-theme identified is that the extent of overlap impacted how youths interact with their environment. After highlighting examples that represent the ends of the continuum, we briefly discuss variation in the continuum to illustrate that the youths’ experiences do not always neatly fall into one of these poles. Quoted participants are identified by their age, self-reported gender, and self-reported sexual orientation.

Overlapping family and LGBTQ experiences: One end of the continuum

A range of comments demonstrated overlap between parent-child relationships and the LGBTQ experience. Feeling free to have open conversations about gender and sexuality provided one example: “[My parents are] both just really focused on loving their kids and loving me. Even last night, I was talking, telling my family about how I identify gender- and sexuality-wise” (18-year-old, gender-fluid, queer). Another youth said, “[My mom] was actually going to come with me yesterday to the pride parade, but she had a benefit” (18-year-old, female, lesbian). Overlap in these experiences did not mean that youth talked openly with their parents about all issues pertaining to their LGBTQ experience, rather it meant that they felt they could be themselves and talk about as much as they would if they were straight. For example, one participant stated, “[I talk about dating] the same way that I would if it was a girl […] I just, I wouldn’t talk about it much at all” (14-year-old, male, bisexual). Overlap in these areas of experience was also seen in shared emotions: “When they had the VOTE NO [on a marriage amendment] signs, there were a lot of NO signs, and I was crying because I was so happy. Me and my mom just started crying and bawling” (16-year-old, trans* female, straight). For some youth, overlap existed or was made easier because another family-member (e.g., a parent or aunt) identifies as LGBTQ.

Parents contribute to and reinforce overlap

Regardless of how fully out youth were to their parents about their LGBTQ status, parents contributed to this overlap by behaving in ways that facilitated a safe and accepting environment. A generally safe and accepting environment was seen in participants’ statements indicating that their family is supportive, and in some coming out experiences: “I have much more privilege, compared to other LGBTQ people. I totally admit that, because my family completely supports me. My coming-out process consisted of, ‘Hey, are you gay?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah,’ and then my mom said, ‘Okay’” (17-year-old, male, gay). Youth described critical opportunities for parents to contribute to increasing overlap when they came out. Even if unexpected, an accepting response created opportunities for youth to share about their identity:

I was like, ‘Mom, I’m bi-curious,’ and she was like, ‘Oh, that’s cool. I never knew how it would feel to have a son like that, but I guess I do now. It feels so awesome.’ I was like, ‘Aw, thank you.’ She took it better than I thought she would. (14-year-old, male, bisexual)

After youth were out to their parents, participants described numerous ways that parents could contribute to the feedback loop promoting overlap. Some parents demonstrated that they were interested and willing to learn: “[My mom] tries to educate herself so she can be supportive for me, and if I have problems, I can go to her” (18-year-old, female, lesbian). Other parents conveyed to their children that they wanted to be a part of every piece of their child’s identity by making an effort to learn and understand: “[My dad] hasn’t really gotten to the correct pronouns yet. My mom has really been working on it” (14-year-old, gender-neutral, pansexual).

Some accepting behaviors by parents were present in day-to-day interactions. One youth said, “[My mom is] very supportive. She’s at the point of comfort with it that she makes jokes about it, actual funny jokes” (16-year-old, non-binary, same-sex attraction). A few youth talked about parents mentioning or emailing LGBTQ-related political or pop culture information:

When I came out to my mom I loved that she just instantly, anything gay she would look up. It got kind of annoying, but anything gay she would look up and one day we were at the dinner table and we were watching her show. She pauses it and she was like, ‘you know what I found out?’ I’m like, ‘what?’ she was like, ‘that guy and that guy are both bisexual in real life,’ and I was like, ‘really!’ She was like, ‘yeah. They have a wife, they have kids, and I never would have known it.’ (18-year-old, male, bisexual)

Other accepting behaviors were even more direct. One participant stated, “My parents have often said ‘what can we do to be more supportive?’” (18-year-old, trans* gender-fluid, gay). Another youth said, “[My mom is] really the only one who really knows ‘cause we have deep conversations and she’s just, like, no matter what, know that I love you and I will support you. Without her I don’t even know” (17-year-old, trans* male, pansexual). Other accepting behaviors included public displays of support, “[At] the pride parade I got marriage equality bumper stickers […], I asked my mom if she wanted to put one on our car. She’s like, ‘Okay,’ and she just went and put it on her car” (17-year-old, male, gay). Youths also identified ways that parents went out of their way to be involved in their LGBTQ identity:

My dad wants me to find a job in a field that I’m interested in, and he knows that I really like make-up, so the other day, he sent me a bunch of links to applications to different make-up booths at Macy’s. I thought that was nice, because, I mean, a guy wearing make-up isn’t necessarily the norm. (18-year-old, trans* gender-fluid, gay)

For transgender youth, parents’ use of proper pronouns created overlap in their experience in their family and their LGBTQ experience. One participant said, “Even when [mom is] talking to her friends, she’s trying to go with he, him, [participant’s chosen name], so it’s just – it’s really helpful” (17-year-old, trans* male, panromantic asexual). This participant also recounted a particular moment of feeling like his identity was acknowledged,

At Christmas [mom] gave me, like, I opened up one present and it was boxers. And she’s, like, I know, honey, it’s okay. And she just gave me a hug and I was, like, crying. ‘Cause it was like the first male gift I got. (17-year-old, trans* male, panromantic asexual)

Youth contribute to and reinforce overlap

Youths in our study also described behaviors that contributed to this overlap such as coming out to parents, sharing information with their parents, and helping their parents learn about LGBTQ issues. Youths’ behaviors to promote overlap were largely responsive to their perception of their parents’ acceptance; youths were more likely to include parents in their LGBTQ identities when parents showed love and acceptance as seen in the previous section. In other words, participants took small steps towards overlap based on the steps parents took to demonstrate support, which then gave parents new opportunities to demonstrate support and acceptance.

Youth who felt comfortable with their parents and believed their parents would be supportive felt free to be open about their LGBTQ identity:

When I first came out, I actually did the exact opposite from what a lot of LGBTQ youth do. I found that almost all of my friends started coming out to friends before they came out to their parents. But I have a very special relationship with my parents. (18-year-old, trans* gender-fluid, gay)

When talking about moving across the country after a divorce, another participant spoke about differing levels of comfort with different parents and said, “I’m glad I grew up here compared to [with my dad]. I feel like my LGBT experience would have been much different... because even though my mom is supportive, my dad would have had a problem” (17-year-old, male, gay).

Participants talked about educating their parents about their personal identities but also about more general information:

I had to explain gender to my mom the other day because my brother’s having a baby, and she was like, ‘Something blah blah gender,’ and I was like, ‘Well, the sex,’ and she was like, ‘Cool. What’s the difference?’ (17-year-old, female, lesbian)

One youth described a willingness to start conversations about gender and sexuality with parents, sharing, “I think I found a label for who I am, and like my gender. And [mom] was, like, okay, lay it on me” (14-year-old, gender-neutral, pansexual). Another talked about bringing home a boyfriend and said, “He came to my house, which is fine because my parents are completely accepting” (18-year-old, male, gay).

Overlap in youth’s LGBTQ and family experience influences interactions with their environment

Some participants with supportive families suggested that they did not feel the need for external support. Other participants who accessed external resources or support reported that their parents helped them find the resources or facilitated their attendance. In other words, when these areas of experience overlapped, some youths reported little need for external support but greater ease in accessing resources if they were wanted.

Those who stated they did not feel the need for extra support said their families were their support; for example, “I haven’t really needed the support as much as a lot of other people, I think, because my family’s very accepting, and so I just haven’t needed that extra support” (17-year-old, female, lesbian). Some youths explained that their parent(s) were their primary resource. One participant was asked where to direct a friend who is having trouble: “Honestly, my mom. My mom is… she’s the world’s best mom” (19-year-old, trans* male, queer). Similarly, when an interviewer asked a participant about searching for resources online, he said,

My mom accepted me, so my take on being LGBTQ was different from other people’s. I guess I didn’t really have a need for resources at the time, when I first came out. I just Googled LGBT organizations because I was bored one day. I was like, ‘Okay, maybe there are other people.’ (17-year-old, male, gay)

This casual response shows that this youth did not feel a strong need for other resources but also had little hesitation about searching for organizations one day.

Youths who experienced overlap between these areas of their lives reported ease in searching for and accessing resources when they decided to look. In some cases, parents facilitated connecting their youth to resources. One participant reported that, “My mom found [my therapist] because I was going through some issues” (17-year-old, trans* male, asexual). For those youths with LGBTQ family members, there was additional overlap in family and LGBTQ experiences, which sometimes resulted in connections to resources. When a participant was asked if her mom - who is a lesbian - helps identify resources, she said, “She sometimes does, but I mostly seek out the resources for myself because she’ll point me in the right direction but I might not need it at that time” (14-year-old, male, gay). Others talked about parents referring them to churches they might like, to clinics, or to potential jobs.

In addition to reporting little need and easy access, some youths talked about shared LGBTQ-related experiences with their parents. For example, “I usually go up to [large city] when we have youth pride. I’ve never been to pride, but I definitely want to go. My mom and I wanted to go, but we had a family event, so we couldn’t” (16-year-old, male, gay).

Overlap between a youth’s experience as a parent’s child and an LGBTQ youth created a more unified existence, as “overlap” suggests; youths and parents shared experiences, parents accepted and sought to know their children, and these youths did not feel the need to hide portions of their lives any more than any other teenager.

Separated parent-child and LGBTQ experiences: The other end of the continuum

Separation between these two experiences or identities were described by youths who were not out to their parents and by youths who were out but perceived their parents to be unaccepting or unsupportive. For example, one participant who was out to family said, “I go home, I’m in my room a lot. My parents aren’t accepting […] so I really don’t talk much at home” (17-year-old, male, gay). Because the extent of overlap or separation falls along a continuum, other youths described being only partially out or only being out to one parent. As an example of being partially out – with distinctly separate family and LGBTQ experiences – a transgender youth who was only out as “not straight” to his parents said,

I’m so happy at school ‘cause everyone’s always like “he” and calling me [participant’s chosen name] and it’s, like, this is actually really nice. And then I go home and it’s just constant “she” and everything like that. […] Everyone that knows [I’m transgender] knows to use male pronouns when my parents aren’t around and female ones, or actually they tend to stick more to neutral ones which is really comforting, around parents so they don’t question it. Like one of my friends, he’s actually going to come down soon and meet me, my mom doesn’t know he’s trans and I was, like, staying over at his place. And she doesn’t like me staying at guy’s places so I was, like, ‘I’m sorry, I have to do this, but I have to refer to you as a girl.’ And I felt so bad. (17-year-old, trans* male, pansexual)

Again demonstrating a feedback loop, the ways parents and youths interacted reinforced this separation. For these youths, expressing their LGBTQ identities and experiencing the LGBTQ community took place hidden from or without the overt inclusion of their parents, largely in response to the perceived lack of supportiveness of their parents.

Parents contribute to and reinforce separation

Parents’ conveyed to participants their lack of acceptance through behaviors or the language they used, such as not using preferred pronouns or referring to the youth’s identity as a “phase.” Passive examples of non-acceptance contributed to the separation but were necessarily less overt than some other examples.

Some parents contributed to the feedback loop reinforcing separation by generally conveying a lack of acceptance before or after their youth came out. One youth recalled, “[My sister] was playing with her Barbie [dolls], made them kiss and my stepmom was, like, you can’t do that […] and then she went and bought her a bunch of Ken dolls” (16-year-old, female, bisexual). Another youth said,

My mom even told me that [my boyfriend] might cheat on me with a guy just because he’s bisexual. I’m like, ‘So you’re basically saying I’ll cheat on him with a girl?’ She’s like, ‘No.’ [I’m like,] ‘You’re basically saying that.’ (14-year-old, female, bisexual)

Examples of overt non-acceptance were easy to identify in what the youths shared, such as, “My mom has kicked me out before for bringing girlfriends home” (19-year-old, gender-neutral, “other” sexual orientation) or, “We were driving by [a church with a sign that] said something about man and woman find each other in a certain way and then get married. And [mom] looked back at me and said, ‘Yeah, man and woman’” (14-year-old, female, lesbian). Exemplifying how these interactions created separation, this participant also said “I don’t talk with my mom. I had the best relationship with my mom, and since I’m different in her eyes, she thinks that that relationship isn’t there anymore.” As another example of unsupportiveness and the resulting separation, a participant recounted a family outing at a restaurant:

We were sitting and [dad] started asking me these questions. And I got really uncomfortable because it was about transgender stuff and about it being an abomination because he’s a hardcore Christian, and I got really uncomfortable, I started shaking, and I just really wanted to leave. And my mom was getting mad at him for doing it in a public place and just how he was saying it in general was making her angry, too. My mom’s not supportive of it, either, but she doesn’t attack me on it. […]. Eventually, after a while I just got up and went and sat over in the sunroom area. [...] One of my friends was there. She saw me shaking. We talked for a while. We actually ended up driving around for like four hours. (18-year-old, male, pan-sexual)

Youth contribute to and reinforce separation

Participants described maintaining and/or promoting separation as a response to feeling unsupported or being unsure how parents would react to their LGBTQ identity. In some of the clearest examples of maintaining separation, some youths talked about not coming out to parents. One said, “I haven’t even told my dad’s side of the family that I’m bisexual, because I already know what I’m going to hear from them: ‘You’re not. That’s not what you are’” (14-year-old, male, bisexual). Others talked about the choice not to come out until being able to move away from home if it did not go well. When youths were not out to one or both parents yet, they unsurprisingly tried to maintain this separation: “The only place that I wouldn’t be talking about any of this kind of stuff would be my house. But that’s just ‘cause I haven’t exactly told my stepdad” (17-year-old, male, bisexual).

For youths who were out but perceived their parents as unsupportive or uninterested, maintaining separation consisted of simply not talking about LGBTQ topics, not bringing LGBTQ friends over, or keeping distance by staying away from home or staying in their rooms. When asked “where would you go to find supportive adults,” one youth said, “I would probably not choose my family, because they’re all haters. I’d probably end up going to my friend’s mom’s house, because she’s lesbian and she knows about it” (14-year-old, female, bisexual).

Separation between youth’s LGBTQ and family experience influences interactions with their environment

Navigating the gap between parents and living as an LGBTQ youth was especially complicated. For youths who were not out to parents, navigating this gap often meant hiding where they had gone, who they saw and the resources they accessed. For youths who were out to parents (or were partially out), navigating the gap involved making decisions to avoid conflict, shaping behavior to reflect parents’ values, or hiding portions of their life. Separation between their LGBTQ experience and their parent-youth experience made it difficult for these youths to access resources, even if they would have greatly benefitted from them.

One participant recounted a time before coming out, “When I was originally looking up youth groups for LGBT kids, the only ones I could find were [far away…]. There’s no way my parents would let me go there without telling them why” (16-year-old, female, lesbian but flexible). Some youth talked about avoiding LGBTQ topics on social media if they were connected on social media to family members. Others said they avoided searching for resources online because they might not have been able to hide it from parents. For example, after saying, “[Mom] kind of knows I’m gay’ish. Well, she doesn’t--well, it’s complicated,” a participant explained that he would search for resources online if needed but he added, “it’s really hard to search something up when the door’s open, like, in my room. And my parents could come at any time and say, like, what are you doing? Like, kind of suspicious” (16-year-old, male, gay).

When participants had easy access to external resources, navigating the separation and not involving parents in their LGBTQ identities was less of an issue. A youth who identified as bisexual said that her parents were generally supportive, but they were not the supportive adults in her life because she was not out to them. She said,

I have a youth worker and I used to have counselors that I can still go to and they gave me their number in case I am having a rough patch. I have two counselors at my school that are lovely, and I have awesome friends. (17-year-old, female, bisexual)

Participants who were out but with parents who were unsupportive made decisions or changed behaviors to avoid backlash. After talking about having a difficult parent-child relationship – in part, because of being out – a youth illustrated feeling the need to make compromises, “At one time I was considering doing a transition […] Maybe someday I’ll be able to transition without fear of total backlash from my family and everyone else, but for now, I’m comfortable with what I am” (19-year-old, gender-neutral, “other” sexual orientation). Providing other examples of ways that separation between parent-child experiences and LGBTQ experiences can change a youth’s interaction with the environment, a participant said,

When you’re sitting in the movie, you’re just always thinking don’t make other people feel uncomfortable. […] My mom’s kind of made that the way I should be, I guess. She always just says, like, other people don’t agree with you, you shouldn’t push it in everyone’s faces. But it sucks when you see a straight couple walking to the movies holding hands but you can’t. (14-year-old, female, lesbian)

She went on to explain in an exchange with the interviewer that her mom told her it’s better if she does not go to church:

Youth: [Mom] told me I shouldn’t go because someone in the church found out.

Interviewer: But would it be a space that you would choose go to if that was not the case?

Youth: Yeah, I love church. I used to sing in the choir, like, I kind of miss that. But I wouldn’t choose lying to myself over going. (14-year-old, female, lesbian)

The difficulties that some youths experienced because of separation between these parts of their lives were in stark contrast to youth who can move through the environment without having to consider a difference between their parent-youth experience and their LGBTQ experience.

The extent of overlap falls on a continuum

The results in previous sections illustrate the ends of the continuum, but participants made it clear that these are not discrete categories. For example, some youths reported great overlap in experiences with one parent but little overlap with another. In these cases, there were scenarios in which both parents lived at home and in others, parents were separated or divorced and living apart. For example, one youth said, “[My stepdad] is really cool; my mom’s really cool. They’ve always been really open and honest and that kind of thing. And I told both of them and they’re fully okay with it,” and also said, “My dad, I dropped a couple of hints and I’m pretty sure he knows, and whenever I bring it up he’s like, oh, it’s cute, blah, blah phases. […] It pisses me off, so we just don’t talk about it” (16-year-old, female, bisexual). Other youths described change in parental responses over time, and talked about difference before they came out or said that parents are learning to use proper pronouns or becoming more accepting of their status.

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to examine a youth perspective of the intersection between parent-youth relationships and youth’s broader environment. Findings led to the development of a novel conceptual model describing a continuum of overlap and separation between LGBTQ adolescents’ experience being LGBTQ and their experience being part of a family, and more specifically being a child of their parents. In the findings, we presented examples that represent each end of this continuum. On one end, participants provided examples of their experiences that suggested that their parent-youth experiences and LGBTQ experiences overlap; on the other end, participants reported examples of separation between these experiences.

As illustrated throughout the findings, overlap might also be understood as living in one world as opposed to two, or having one identity as opposed to separate identities at home and with others. Hirsh and Kang (2015) proposed a model suggesting that identity conflicts of any type (i.e., having different identities in different settings) lead to high levels of anxiety and stress. Following this model, it would make sense that youths who feel they have two (or more) separate identities would try to maintain separation between those settings. When these settings intersect, identity conflicts can arise, which was seen in examples of youths using one set of pronouns with friends at school and a different set with friends when they were near parents.

We also highlighted the ways in which parents and youths both contributed to the extent of overlap between these parts of a youth’s life, a process we conceptualize as a feedback loop. The feedback loop could be described as “starting” with the parents (e.g., by creating a safe and accepting environment before their youth even come out) or by the youth (e.g., by coming out). As the parent-youth relationship progresses, each takes small steps toward overlap or separation, which then create new opportunities for the other. For example, after a youth comes out as “not-straight” a parent can choose to demonstrate acceptance (e.g., “I love you no matter what!”) or not (e.g., “It is just a phase”). If parents demonstrate acceptance, youth might disclose more and eventually might facilitate opportunities for parents to attend LGBTQ events, for example. If parents do not demonstrate acceptance after coming out (or even before youth come out), a youth might simply stay in their room at home or not discuss identity-related topics with parents.

As a feedback loop, the extent of overlap is not necessarily static. Overlap may grow as parents become more accepting, or there may be a great deal of overlap in one parent-youth relationship but not in another. Because of this variation, it was not possible to quantify the degree of overlap or even categorize youths into “high” or “low” experiences of overlap. We also found that the extent of overlap related to participants’ perceived need for external resources, their comfort with and ability to access resources, and the ways they interacted with the broader LGBTQ environment. These findings highlight a strength of this paper as they provide a broader view of youth’s lives than can be achieved when studying family relationships, resources, or environments in isolation. We found that participants who described little overlap (who we presume may most benefit from external resources and support) reported difficulty accessing external support; those with much overlap often reported little need for external support but also little trouble accessing it.

These results may help to explain existing evidence that has found disparate LGBTQ-related experiences for youth in their families and communities and helps to contextualize previous quantitative findings. For example, our findings may help to explain previous quantitative research that has found LGBTQ youth earn better grades and are victimized less at school when they are out to everyone or no one (i.e., not managing different levels of disclosure to parents, friends, classmates; Watson et al., 2015). Because we had no youths in our study who were out to no one (by virtue of our sampling methodology), findings may not extrapolate to this experience. Nonetheless, both our research and previous research on managing sexual orientation disclosure supports the idea that youths who are managing their sexual identities (e.g., out to their friends and peers but not to their parents), encounter more opportunities for frustration and isolation (Watson et al., 2015).

Our paper suggests that the extent of overlap may be more important than simply whether or not a youth is out to parents or peers. Previous research on outcomes related to disclosure of sexual identity to parents has been mixed: in some research, disclosure was associated with increased risk, such as verbal and physical abuse (Corliss, Cochran, Mays, Greenland, & Seeman, 2009; D’Augelli, Hershberger, & Pilkington, 1998). Yet in other research not disclosing was related to illicit drug use, lower self-reported health status, and prolonged depression among women, but not men (Rothman, Sullivan, Keyes, & Boehmer, 2012). However, a more complex picture is painted when considering our results in conjunction with recent evidence that being out in all or no contexts is associated with greater school achievement and lower odds of being bullied (Watson et al., 2015) compared to being out in only some contexts. As evidenced from the findings presented in this paper, parents who are generally accepting and supportive foster an environment in which their youth feels safe coming out, and these parents subsequently participate in the youth’s LGBTQ experience. Conversely, LGBTQ youth who are out to parents but do not feel supported (i.e., experience little overlap), may be at greater risk for negative outcomes, similar to what has been found in other studies.

An emerging body of literature has focused on parental acceptance, support, and attachment (Rosario et al., 2014a; Rosario et al., 2014b, Ryan et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2016b) for LGBTQ youth. It is clear from previous evidence that supportive parents are linked to better psychosocial outcomes for LGBTQ youth (Shilo & Savaya, 2011; Snapp et al., 2015), yet LGBTQ youth live in multiple contexts where support of sexual orientation is imperative for positive experiences. These findings provide insight into the potential inner workings of the LGBTQ youth experiences where family and environment overlap is high so that we can better understand what it is about the LGBTQ ‘fully out’ experience that is related to higher achievement and safer school experiences. Research should continue documenting the overlapping and intersecting experiences of LGBTQ youth, including but not limited to family, school, friends, extracurricular activities, and the broader community.

Also noteworthy is that LGBTQ youth have traditionally disclosed their minority sexual orientation to their parents last (Goodrich & Gilbride, 2010; Savin-Williams, 2001), delaying the potential for parents to be integrated into a youth’s LGBTQ experience. However, at least one participant in this study reported coming out to family first, demonstrating that generally accepting environments can facilitate overlap. While norms around disclosure may be changing as social acceptance of non-heterosexuality has increased, when LGBTQ youth are unsure of how supportive parents will be it creates a challenge for integrating experience across the various contexts. Our findings contribute evidence that when accepting and supportive, parents can create a unified experience for their youth across the family and other social contexts.

Strengths and Limitations

The findings reported here are strengthened by the multi-site, large, and diverse sample. Our findings are also strengthened by the fact that participants were aged 14–19 years, and the majority were still living at home and not yet of legal age (i.e., 18 or older). Given the challenges to conducting research with underage LGBTQ adolescents (Fisher & Mustanski, 2014) and the paucity of research with this population, our study was strengthened by the ability to minimize recall bias compared to studies with older LGBTQ youth. The limitation of the sample is that our method of recruitment necessarily yielded participants who were out to the extent that we were able to reach them through schools and LGBTQ-serving organizations; it is plausible that the experiences of youths not yet out and therefore, not identifiable to participate in this study, are different from their ‘out’ peers. The go-along interview method used is also a strength because it yielded rich data and facilitated participants being in some of the environments they were discussing with the interviewer. However, these interviews did not specifically seek to inquire about families or parenting and so participants discussed family members to varying extents. As a result, the data available about families were limited to quotes about parents for the present paper, because they made up the majority of the substantive family-related quotes. This resulted in our inability to consider other family members that may or may not be supportive, as the participants did not frequently mention these individuals. We conducted our analysis by interpreting and analyzing the many quotes related to family; however, participants may have made more or different comments if we had explicitly asked each participant about their families.

Implications

Insights shared by youths in these findings have valuable implications for practitioners and researchers. A critical starting point to effectively supporting LGBTQ youth and their families is recognizing the complexities inherent in their relationships and the intersection of these relationships with their LGBTQ-specific experiences in and outside of their family environment. It is insufficient to operate with an understanding of whether a youth is or is not out to one or both parents. Family-focused and youth practitioners are in unique positions to assess the extent of relationship-identity experience overlap, which can yield meaningful starting points from which to promote and encourage overlap in non-hostile families, and to carefully consider supportive alternatives in the absence of possible overlap/intersection. For some youths, overlap is not possible: this presents unique needs for support in identifying and accessing resources that many youths might need and not be aware of, or might be aware of but are unable to safely access without support (e.g. transportation, financial resources). Parents might need education and tools to effectively support their youth and to foster an environment that encourages their youth to come out to them and to actively encourage overlap in their relationships and experiences. Practitioners will benefit from giving attention to both youth and parents as agents of change who can strengthen and foster, or inhibit healthy relationship and subsequent overlap. Arguably, for most youths in a healthy family environment, overlap will be more protective than the absence of overlap but one should not assume this without careful knowledge of the multi-faceted interpersonal family dynamics and relationships.

In practical terms, family nurses and other health practitioners should familiarize themselves with local and online resources for LGBTQ youth and their families (e.g., http://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/youth-resources.htm). Their familiarity with resources should include knowing where youth can obtain confidential services. To assess the need for additional support, practitioners can ask youth patients if they are out to their parents, how comfortable they are talking about LGBTQ-related issues with their parents, and how much family support they perceive around their sexual orientation. When a youth is out to parents, practitioners can ask parents how comfortable or knowledgeable they feel with LGBTQ issues. Based on answers to these types of questions, practitioners can guide the youth and families to resources that might fit their needs. For example, youths with much separation between their LGBTQ experiences and their family life might be most receptive to learning about confidential services or being encouraged to attend a Gay-Straight Alliance club at school. Parents who are aware of their youth’s LGBTQ identity might be encouraged to attend a local PFLAG group.

Availability of resources is critical, regardless of whether the resource is located in a community-based agency, a school, a faith-based organization, or another formal or informal institution. For youths who do not feel supported by their family, it is critical that these resources be easily accessible and confidential; organizations should strive to address these needs. Regardless of the extent of overlap a youth perceives, supportive resources can promote changes over time in relationships, shared experiences, and independence as the adolescent moves into young adulthood.

Researchers can build on these findings by taking into account the overlap between youth-parent relationships and LGBTQ identities and experiences. Adolescents’ social and relational dynamics are complex and it is not enough to simply focus on or assess broad factors such as parental acceptance or whether or not a youth is out to one or both parents. For example, researchers could utilize measures and previous findings related to identity conflicts. The field may also benefit from a validated measure of overlap or of the degree to which LGBTQ youth feel they must be different people in different environments. With such a measure, quantitative research could explore the effects of the extent of overlap on outcomes. Even in the absence of such a measure, research that explores LGBTQ healthy youth development must recognize the complex intersections and the transient nature of experiences and avoid the temptation to distill youth experiences of acceptance to simple and discrete variables.

Conclusion

The extent to which LGBTQ youth experience overlap between their parent-youth relationships and their LGBTQ experiences is iteratively constructed through acceptance and behaviors by both parents and youth. The message for researchers is that this complex interaction may be more important than simple measures of acceptance. The task for clinicians and youth-workers is to provide accessible and confidential resources, and to cautiously encourage greater overlap where it is safe and appropriate to do so. The lesson for parents is that making unconditional support explicit and discussing gender and sexual identity before a youth comes out is imperative; not discussing these topics will not change a youth’s identity, but it might limit how much of that identity youths share with their parents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD078470. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Mehus is also supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services (HHS) under National Research Service Award in Primary Medical Care grant number T32HP22239 (PI: Borowsky), Bureau of Health Workforce. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Biographies

Christopher J. Mehus is a postdoctoral fellow in the Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health at the University of Minnesota. His research focuses on parenting, parent-child relationships, and parenting interventions.

Porta, C.M., Singer, E., Mehus, C., Gower, A., Saewyc, E.M., Fredcove, W., & Eisenberg, M.E. (in press). LGBTQ Youth’s views on Gay-Straight Alliances: Building community, providing gateways, and representing safety and support. Journal of School Health

Leslie, L., Mehus, C., Hawkins, J. D., Boat, T., McCabe, M. A., Barkin, S., Perrin, E., Metzler, C., Prado, G., Tait, V. F., & Beardslee, W. (2016). Primary health care: Potential home for family-focused preventive interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(4), S106–S118.

Ryan J. Watson is an Assistant Professor at the University of Connecticut in the department of Human Development and Family Studies. His scholarly interests include the study of LGBTQ youth, their mental health, academic success, family experiences, and other protective factors.

Watson, R.J., Adjei, J., Saewyc, E, Homma, Y., & Goodenow, C. (2016). Trends and disparities in disordered eating among heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, Early View, 1–10. doi: 10.1002/eat.22576

Watson, R.J., Grossman, A.H., & Russell, S.T. (2016). Sources of social support and mental health among LGB youth. Youth & Society, Ahead of Print, 1–19. doi: 10.1177/0044118X16660110

Marla E. Eisenberg is an Associate Professor in the Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health at the University of Minnesota. Her research focuses on social influences on high risk health behaviors among adolescents and young adults, with a particular emphasis on health issues of LGBTQ youth.

Porta, C.M., Corliss, H., Wolowic, J., Johnson, A., Fogel, K., Gower, A., Saewyc, E. & Eisenberg, M. (in press). Go-along interviewing with LGBTQ youth in Canada and the U.S. Journal of LGBT Youth

Eisenberg, M.E., McMorris, B.J., Gower, A.L., Chatterjee, D. (2016). Bullying victimization and emotional distress: Is there strength in numbers for vulnerable youth? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 86:13–19.

Eisenberg, M.E., Gower, A., McMorris, B., Bucchianeri, M. (2015). Vulnerable bullies: Perpetration of peer harassment in youth across sexual orientation, weight and disability status. American Journal of Public Health, 105:1784–1791.

Heather L. Corliss is Professor in the Graduate School of Public Health and Core Investigator with the Institute for Behavioral and Community Health at San Diego State University. She studies health disparities of LGBT populations and ways to ameliorate them and improve population health.

Porta, C.M., Corliss, H., Wolowic, J., Johnson, A., Fogel, K., Gower, A., Saewyc, E. & Eisenberg, M. (in press). Go-along interviewing with LGBTQ youth in Canada and the U.S. Journal of LGBT Youth

Calzo J.P., Masyn K.E., Austin S.B., Jun H-J., Corliss H.L. (2016). Developmental latent patterns of identification as mostly heterosexual versus lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Journal of Research on Adolescence. Ahead of print. DOI: 10.1111/jora.12266

Corliss H.L., Birkett, R., Newcomb, M.E., Buchting, F.O., Matthews, A.K. (2014). Sexual-orientation disparities in adolescent cigarette smoking: intersections with race/ethnicity, gender, and age. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6): 1137–47.

Carolyn M. Porta is Associate Professor and Director of Global Programming in the School of Nursing at the University of Minnesota. Her research and clinical interests are focused on promoting the health of vulnerable young people, specifically addressing stigma, emotional health, and sexual violence.

Porta, C.M., Singer, E., Mehus, C., Gower, A., Saewyc, E.M., Fredcove, W., & Eisenberg, M.E. (in press). LGBTQ Youth’s views on Gay-Straight Alliances: Building community, providing gateways, and representing safety and support. Journal of School Health

Porta, C.M., Corliss, H., Wolowic, J., Johnson, A., Fogel, K., Gower, A., Saewyc, E. & Eisenberg, M. (in press). Go-along interviewing with LGBTQ youth in Canada and the U.S. Journal of LGBT Youth

Porta, C.M., Allen, M., Hurtado, A., Padilla, M., Arboleda, M., Svetaz, M., Balch, R., & Sieving, R. (2016). Honoring roots in multiple worlds: Professionals’ perspectives on healthy development of Latino youth. Health Promotion Practice, 17(2), 186–198

Contributor Information

Christopher J. Mehus, Postdoctoral Fellow, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota, 717 Delaware St, SE, 3rd Floor West, Minneapolis, MN 55414, P: 651-785-3660, F: 612-626-2134.

Ryan J. Watson, Assistant Professor, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of Connecticut, 348 Mansfield Road, U-1058, Storrs, CT 06269, P: 860-486-1659, F: 860-486-3452.

Marla E. Eisenberg, Associate Professor, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota, 717 Delaware St, SE, 3rd Floor West, Minneapolis, MN 55414, P: 612-624-9462, F: 612-626-2134.

Heather L. Corliss, Professor, Graduate School of Public Health, 9245 Sky Park Court, Suite 100, San Diego, CA 92123, P: 616-594-3470, F: 619-594-1758.

Carolyn M. Porta, Associate Professor, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, 5-140 Weaver-Densford Hall, 308 Harvard Street SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, P: 612-624-6179, F: 612-624-3174.

References

- Bronfenbrenner U. Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development. 6. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano RM. Come take a walk with me: The “Go-Along” interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & Place. 2009;15(1):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo AL, London CB. Parents and schools: A source book. New York, NY: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Greenland S, Seeman TE. Age of minority sexual orientation development and risk of childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts in women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(4):511–521. doi: 10.1037/a0017163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(3):361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty ND, Willoughby BL, Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:1134–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DT, Hatzenbuehler ML. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender hate crimes and suicidality among a population-based sample of sexual-minority adolescents in Boston. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(2):272–278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Wechsler H. Social influences on substance-use behaviors of gay, lesbian, and bisexual college students: findings from a national study. Social Sciences & Medicine. 2003;57(10):1913–1923. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Mustanski B. Reducing health disparities and enhancing the responsible conduct of research involving LGBT youth. Hastings Center Report. 2014;44:S28–S31. doi: 10.1002/hast.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J. Bullying and bias: Making schools safe for gay students. Leadership. 2012;41(4):12–14. Retrieved from: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ971411. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C, Eisenberg M, Frerich E, Letner K, Lust K. Conducting go-along interviews to understand context and promote health. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22(10):1395–403. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich KM, Gilbride DD. The refinement and validation of a model of family functioning after child’s disclosure as Lesbian, Gay or Bisexual. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2010;4:92–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127:896–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh JB, Kang SK. Mechanisms of identity conflict; Uncertainty, anxiety, and the behavioral inhibition system. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1088868315589475. advanced online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta CM, Corliss H, Wolowic J, Johnson A, Fogel K, Gower A, Saewyc E, Eisenberg M. Go-along interviewing with LGBTQ youth in Canada and the U.S. Journal of LGBT Youth. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2016.1256245. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Sinclair KO, DiGiovanni CD, Koenig BW, Russell ST. Gay-straight alliances are associated with student health: A multischool comparison of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;23(2):319–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00832.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Reisner SL, Corliss HL, Wypij D, Calzo J, Austin SB. Sexual-orientation disparities in substance use in emerging adults: A function of stress and attachment paradigms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014a;28(3):790–804. doi: 10.1037/a0035499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Reisner SL, Corliss HL, Wypij D, Frazier AL, Austin SB. Disparities in depressive distress by sexual orientation in emerging adults: The roles of attachment and stress paradigms. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014b;43(5):901–916. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0129-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: critical role of disclosure reactions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(1):175–184. doi: 10.1037/a0014284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Sullivan M, Keyes S, Boehmer U. Parents’ supportive reactions to sexual orientation disclosure associated with better health: Results from a population-based survey of LGB adults in Massachusetts. Journal of Homosexuality. 2012;59(2):186–200. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.648878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;23(4):205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Mom Dad I’m gay. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shilo G, Savaya R. Effects of family and friend support on LGB youths’ mental health and sexual orientation milestones. Family Relations. 2011;60(3):318–330. [Google Scholar]

- Shilo G, Savaya R. Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and young adults: Differential effects of age, gender, religiosity, and sexual orientation. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22(2):310–325. [Google Scholar]

- Snapp SD, Watson RJ, Russell ST, Diaz RM, Ryan C. Social support networks for LGBT young adults: low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Family Relations. 2015;64(3):420–430. [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Grossman AH, Russell ST. Sources of social support and mental health among LGB youth. Youth & Society. 2016a doi: 10.1177/0044118X16660110. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Barnett MA, Russell ST. Parent support matters for the educational success of sexual minorities. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2016b;12(2):188–202. doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2015.1028694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Wheldon CW, Russell ST. How Does Sexual Identity Disclosure Impact School Experiences? Journal of LGBT Youth. 2015;12(4):385–396. [Google Scholar]

- Whitchurch GG, Constantine LL. Systems theory. In: Boss PG, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK, editors. Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 325–352. [Google Scholar]