ABSTRACT

We report an autopsy-verified case of steroid-responsive encephalopathy with convulsion and a false-positive result from the real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QUIC) assay. A 61-year-old Japanese man presented with acute onset of consciousness disturbance, and convulsions, but without a past medical or family history of progressive dementia, epilepsy, or prion disease. Brain diffusion and fluid-attenuated inverted recovery MR images revealed edematous cortical hyper-intensity, which diminished after the acute phase. Steroid pulse therapy was partially effective, although he continued to have dementia with myoclonus and psychiatric symptoms, despite resolution of the consciousness disturbance. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a normal cell count, with significantly elevated levels of 14–3–3 protein and total tau protein. In addition, prion protein in the CSF was slowly amplified by the RT-QUIC assay. PRNP gene analysis revealed methionine homozygosity at codon 129 without mutation. The patient died of sudden cardiac arrest at 3 months after the onset of symptoms.

The positive result from the RT-QUIC assay led us to suspect involvement of prion disease, although a postmortem assessment revealed that he had pathological changes after convulsion, and no prion disease. This case indicates that convulsion may cause false-positive RT-QUIC results, and that a postmortem evaluation remains the gold standard for diagnosing similar cases.

KEYWORDS: 14–3–3 protein, anticonvulsant, convulsion, corticosteroid, encephalopathy, MRI, postmortem study, real-time quaking-induced conversion assay, total tau-protein, prion disease

Introduction

Early clinical symptoms of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) may overlap with those of other non-prion encephalitis/encephalopathy (e.g., autoimmune-mediated or steroid-responsive encephalopathy). However, acute-onset consciousness disturbance or convulsions are not typical initial symptoms of sCJD. In most cases, it is relative straightforward to distinguish between sCJD and non-prion encephalopathy on the basis of the patient's clinical history, steroid-responsiveness, radiological findings, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis results. However, CSF levels of 14–3–3 protein and/or tau protein are reportedly elevated in both sCJD and status epilepticus with non-prion disease.1,2 In addition, cortical hyper-intensity in diffusion-weighted MR images (DW-MRI) is observed during the acute phases of status eplepticus3 and CJD. Furthermore, V180I genetic CJD (gCJD) exhibits cortical-edematous hyper-intensities on DW-MRI,4,5 which is similar to the acute phase of status epilepticus. Thus, non-prion encephalitis/encephalopathy with convulsion is an important differential diagnosis of prion disease. However, prospective MRI studies have revealed that cortical hyper-intensity can last for 24h to 6 weeks, even in case of well-controlled status epilepticus.3 Moreover, this duration is shorter than the duration in V180I gCJD in serial MRI studies.5 Therefore, CSF samples and/or MRI from the acute phase of status epilepticus or convulsion state may confound the diagnosis of prion disease.

Recent studies have confirmed that real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QUIC) testing of CSF provides high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing prion disease.6,7 A few cases with potentially false-positive results have also been reported, although the reports did not contain complete pathological infromcation.7 Thus, it is unclear whether these cases involved subclinical prion disease in their brain, and pathological analysis remains critical for confirming RT-QUIC results. We report a case of autopsy-verified steroid-responsive encephalopathy with convulsion and a false- positive result from the RT-QUIC assay.

Methods and Results

The Patient Characteristics and Clinical Course

A 61-year-old Japanese man presented with acute-onset consciousness disturbance (a Japanese coma scale score of 200), fever, and elevated serum creatinine kinase levels in mid-September 2010. He had no medical or familial history of central nervous system disease, and brain MRI revealed no obvious finding, even on the DW and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. The patient was subsequently admitted to an emergency hospital, and routine CSF testing revealed a normal cell count with a mildly elevated protein concentration (59 mg/dl). Convulsion was noted in late-September, and DW and FLAIR images revealed cortical edematous hyper-intense areas in the bilateral frontal, insula, central posterior, and cingulate gyri (Fig. 1). Herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalopathy was suspected, and the patient began treatment using intravenous acyclovir (1500 mg/day until his CSF tested negative for HSV genomic PCR), and methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1000 mg/day for 3days). The patient also received anticonvulsant, which controlled his convulsions. His disturbed consciousness gradually improved, and myoclonus was observed in his right upper limb. He was transferred to our hospital, and our neurological examination showed dementia, psychiatric symptoms, a startle reaction, myoclonus, truncal and limb rigidity, and spasticity in all four limbs. Muscle weakness, atrophy, and fasciculation were not observed. A clinical diagnosis of steroid-responsive encephalopathy was made on the basis of steroid responsiveness, although we did not detect well-characterized onconeuronal antibodies or newly autoimmune encephalitis associated autoantibodies (anti-NMDA receptor, anti-LGI1, anti-Caspr2, mGluR5, and anti-GABAB receptor antibodies)8 in his serum and CSF.

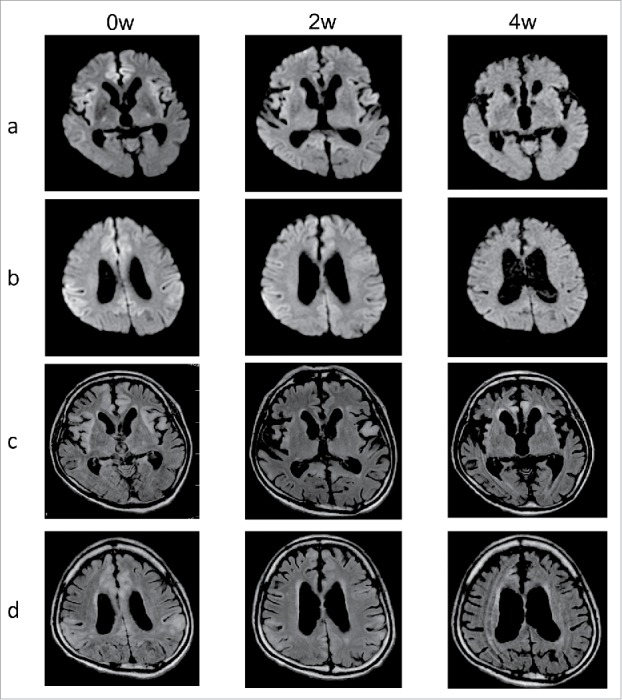

Figure 1.

Serial MR images of diffusion weighted and fluid-attenuated inverted recovery. Lines a and b show serial diffusion-weighted MR images. Lines c and d show serial fluid-attenuated inverted recovery (FLAIR) MR images. The images were obtained at 0 weeks (0w), 2 weeks (2w) and 4 weeks (4w) after the convulsions. The serial images revealed edematous cortical hyper-intense areas in the brain cortices during the acute phase, and the hyper-intensity had diminished within 4 weeks.

Serial DW and FLAIR images during the acute phase revealed edematous cortical hyper-intense areas in the brain cortices, although the hyper-intense signals diminished within 1 month (Fig. 1). We observed progressive atrophy of the brain cortices mainly the temporal lobes during the disease's course. Periodic sharp-wave complexes were not observed on the serial electroencephalograms. The CSF analysis revealed positive results for 14–3–3 protein and an elevated total tau protein level (7120 pg/ml). The neuron-specific enolase levels in the CSF were 40 ng/ml during the acute phase and 11 ng/ml after his convulsions were controlled. Prion protein (PrP) in the CSF was slightly and slowly amplified by RT-QUIC assay. PRNP gene analysis of peripheral blood DNA revealed methionine homozygosity at codon 129, with no mutations. Despite treatment, the patient continued to have dementia, psychiatric symptoms, a startle reaction, motion-triggered myoclonus, truncal and limb rigidity and spasticity in all four limbs. The patient was transferred back to the original hospital, and we visited him for weekly follow-ups,9 although he died because of sudden cardiac arrest approximately 3 months after the onset of his symptoms.

On the basis of the positive RT-QUIC result, we suspected that the patient had prion disease. However, he did not exhibit akinetic mutism or periodic sharp-wave complexes on the serial electroencephalogram. Nevertheless, the patient exhibit dementia, myoclonus, rigidity, and spasticity and died within 2 y after having a positive result for 14–3–3 protein in his CSF. These clinical findings appeared to fulfill the World Health Organization's diagnostic criteria for prion disease, although he also had acute-onset consciousness disturbance, convulsions, and a partially steroid-responsive course. We obtained informed consent from his family for a postmortem evaluation.

Neuropathological Analysis

A postmortem study was performed 13 h after death with informed consent from his family. The brain was fixed in 20% neutral-buffered formalin for 2 weeks, and tissue blocks were immersed in 95% formic acid for 1 h to inactivate prion infectivity. For the routine neuropathological examinations, sections were subjected to hematoxylin-eosin, Klüver-Barrera and Gallyas-Braak staining. Immunostaining for hyperphosphorylated tau (AT-8; 1:1000: Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) was performed. Immunohistochemical analyses were performed using a monoclonal antibody against PrP (3F4, 1:100; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) after hydrolytic autoclaving for antigen retrieval,10 and immunostaining for PrP was performed using an EnVision Plus Kit (Dako) based on previous reports.11,12

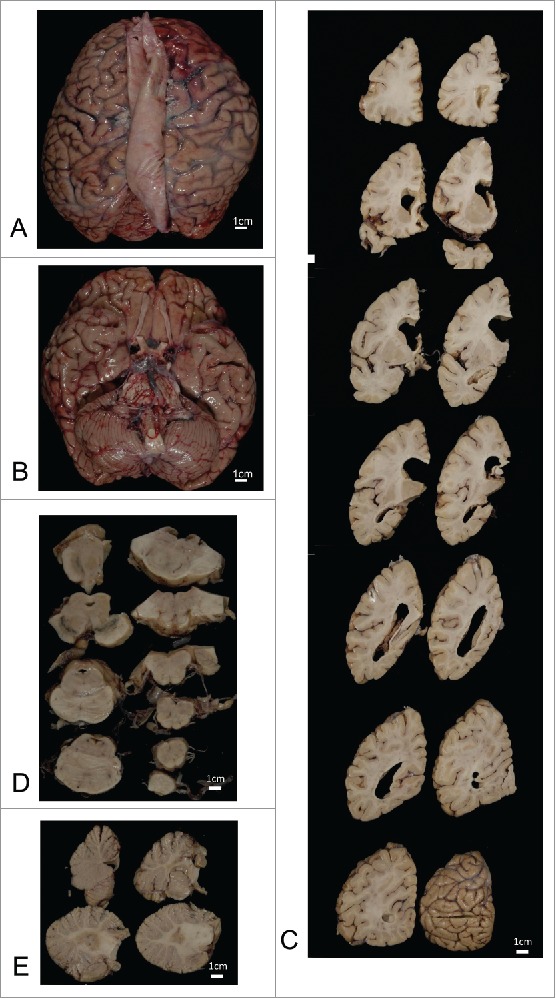

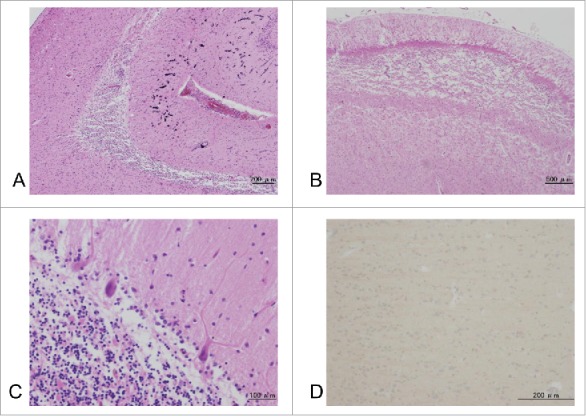

Macroscopic examination revealed no obvious atrophy of the cerebrum, brainstem, or cerebellum (Fig. 2A, B), and the vertebral and basilar arteries were preserved. Coronal sections revealed hippocampal atrophy and thinning of the frontal and parietal cortices (Fig. 2C). Microscopic examination revealed focal brain softening and severe atrophy with loss of neuronal cells, gliosis, and macrophages from hippocampal CA1 to the subiculum (Fig. 3A). Laminar necrosis in the second and the third cortical layers was observed in the cingulate gyrus and frontal cortex (Fig. 3B). Mild neuronal loss and gliosis, with rod-like microglia and inflated neurons, were observed in the deep cortical layers. Mild loss of Purkinje cells and deep-stained remaining Purkinje cells were also observed (Fig. 3C). No obvious abnormalities were observed in the cerebellar dentate nuclei. Geriatric changes were mild as the NFT Braak stage I using Gallyas-Braak staining and AT-8 immunostaining. Argyrophilic grain, senile plaque or Lewy bodies were not found in the brain. PrP immunostaining reveal no obvious PrP deposits in the brain (Fig. 3D). These pathological changes appear to have been caused by the convulsions, and prion disease was excluded from the pathological diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Macroscopic findings. The whole brain before fixation (A, B). Serial coronal sections of the left cerebral hemisphere (C), axial sections of the brainstem (D), and sagittal sections of the cerebellum (E). The brain did not exhibit any macroscopic sings of cerebrum, brainstem, or cerebellum atrophy. Coronal sections of the cerebral hemisphere revealed hippocampal atrophy and thinning of the frontal and parietal cortices.

Figure 3.

Microscopic findings. Tissue sections were stained using hematoxylin-eosin (A-C), and with prion protein (PrP) immunostaining (D). Microscopic analyses revealed focal brain softening and severe atrophy, with loss of neuronal cells, gliosis, and macrophages, from hippocampal CA1 to the subiculum (A). Laminar necrosis in the second and the third cortical layers is observed in the cingulate gyrus and frontal lobe (B). Mild neuronal loss and gliosis, with rod-like microglia and inflated neurons, are visible in the deep cortical layers. Mild loss of Purkinje cells and deep staining of the remaining Purkinje cells are also observed. PrP immunostaining revealed negative results in the cerebral cortex (D).

Western Blot Analysis of the Protease Resistant PrP

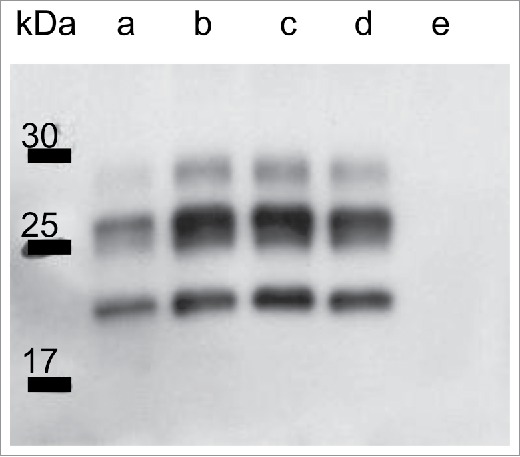

The cryopreserved right frontal lobe and thalamic sections were homogenized and subjected to Western blot subjected analysis of protease-resistant PrP using 3F4, as previous described.11 The Western blot analysis revealed no PrP-positive bands (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of the protease-resistant prion protein from frozen brain extracts using 3F4 antibodies. Lanes a, c, and d: control samples from cases of MM1 sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), Lane b: a control sample from a case of MM1 dura CJD, Lane e: a sample from the present case. Each sample was obtained from the patients’ frontal lobe.

Discussion

In the present case, the clinical course was extremely atypical for prion disease, although we suspected involvement of prion disease based on the positive RT-QUIC result. The postmortem evaluation supported the diagnosis of encephalopathy with convulsion, although clinical or subclinical prion disease was excluded on the basis of PrP immunostaining and Western blot results. Therefore, the present case involved a false-positive result from the RT-QUIC assay.

The RT-QUIC assay is relatively new, but reportedly provides a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 99% for diagnosing CJD.7 False-positive results from this assay are rare, and we reviewed the 5 reported cases (including the current case) with potentially false-positive RT-QUIC results (Table 1).7,13,14 One sample was from a patient with clinically possible Alzheimer disease and the other sample was form a patient with from a patient with convulsion, elevated CSF levels of total tau and 14–3–3 proteins, and cortical hyper-intense areas in MRI.7 However, the reports did not provide complete pathological information, and it is impossible to exclude the possibility of subclinical or clinical prion diseases. We recently reported a case of pathologically-confirmed frontotemporal lobar degeneration-TAR DNA-binding protein 43 kDa with motor neuron disease and false-positive result of RT-QUIC results, in which prion disease was excluded based on the PrP immunostaining and Western blot results.13 However, a case of pathologically-confirmed diffuse Lewy body disease with PrP-positive bands during Western blot analysis has been reported,14 and the authors suspected the case involved subclinical prion disease. In contrast, the present case did not involve subclinical or clinical prion diseases, and it remains unclear how the false-positive RT-QUIC results are obtained, although it is possible that they are related to neuronal damage caused by convulsion.

TABLE 1.

Cases with false-positive result from the RT-QUIC assay.

| Case number | Author (year) | Age of onset/ sex | Underlying non-prion disease | Result from the RT-QUIC using CSF | Pathological analysis for prion disease (PrP immunostaining/WB) | 14–3–3 protein/ t-tau protein (pg/dl) in CSF | DW MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cramm et al. (2016)7) | N.A. | Possible AD | Possible false positive | Not performed | N.A./ N.A. | N.A. |

| 2 | Cramm et al. (2016)7) | N.A. | Encephalopathy presenting with convulsion | Possible false positive | Not performed | +/ N.A. | Cortical hyperintensity |

| 3 | Hayashi et al. (2016)13) | 69/F | FTLD-TDP43 with MND | False positive (slowly amplified) | −/ − | −/ 226 | No abnormal findings |

| 4 | Foutz et al. (2017)14) | N.A. | DLB | Possible false positive | N.A./ + | N.A./ N.A. | N.A. |

| 5 | Present case | 61/M | Steroid-responsive encephalopathy presenting with convulsion | False positive (slowly amplified) | −/ − | +/ 7200 | Edematous coritical hyperintensity during acute phase |

AD: Alzheimer disease; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; DLB: diffuse Lewy body disease; DW MRI: diffusion weighted MRI; F: female; FTLD-TDP43: frontotemporal lobar degeneration-TAR DNA-binding protein 43 kDa; M: male; MND: motor neuron disease; N.A. not available or no discription; NSE: neuron-specific enolase; PrP: prion protein; RT-QUIC: real-time quaking-inversion; WB: Western blot; +: positive; −: negative.

A CSF work-up is useful for diagnosing prion disease and/or distinguishing between prion and non-prion diseases. However, in cases of encephalopathy with convulsion or status epilepticus, the CSF obtained during the acute phase may not be suitable for the RT-QUIC assay or testing for 14–3–3 protein and total tau proteins. Therefore, a postmortem diagnosis should be performed for cases with atypical CJD or concurrent suspected prion disease.13,15

ABBREVIATIONS

- CJD

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease;

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid;

- DW

diffusion-weighted;

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery;

- JCS

Japan coma scale;

- gCJD

genetic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease;

- HSV

herpes simplex virus;

- NSE

neuron-specific enolase;

- PrP

prion protein;

- RT-QUIC

real-time quaking-induced conversion;

- sCJD

sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Joseph Dalmau (Pennsylvania University) for studying the anti-NMDAR, anti-LGI1, and other autoantibodies that are associated with autoimmune-mediated encephalitis/encephalopathy.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Research Committee of Prion Disease and Slow Virus infection (for YI, TK, and KS), and from the Research Committee of Prion Disease Surveillance (for TK, KS, and TI), the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

REFERENCES

- [1].Stoeck K, Sanchez-Juan P, Gawinecka J, Green A, Ldogana A, Pocchiari M, et al.. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker supported diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and rapid dementia: a longitudinal multicenter study over 10 years. Brain 2012; 135:3051-61; PMID:23012332; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/brain/aws238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Monti G, Tondelli M, Giovannini G, Bedin R, Nichelli PF, Trenti T, Meletti S, Chiari A. Cerebrospinal fluid tau proteins in status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav 2015; 49:150-4; PMID:25958230; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jabeen SA, Cherukuri P, Mridula R, Harshavardhana KR, Gaddamanugu P, Sarva S, Meena AK, Borgohain R, Rani YJ. A prospective study of diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in patients with cluster of seizures and status epilepticus. Clin Neurol Neruosurg 2017; 155:70-4; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jin K, Shiga Y, Shibuya S, Chida K, Sato Y, Konno H, Doh-ura K, Kitamoto T, Itoyama Y. Clinical features of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with V180I mutation. Neurology 2004; 62:502-5; PMID:14872044; https://doi.org/ 10.1212/01.WNL.0000106954.54011.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hayashi Y, Yoshikura N, Takekoshi A, Yamada M, Asano T, Kimura A, Satoh K, Kitamoto T, Inuzuka T. Preserved regional cerebral blood flow in the occipital cortices, brainstem, and cerebellum of patients with V180I-129M genetic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in serial SPECT studies. J Neurol Sci 2016; 370:145-51; PMID:27772745; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jns.2016.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Atarashi R, Satoh K, Sano K, Fuse T, Yamaguchi N, Ishibashi D, Matsubara T, Nakagaki T, Yamanaka H, Shirabe S, et al.. Ultrasensitive human prion detection in cerebrospinal fluid by real-time quaking-induced conversion. Nat Med 2011; 17:175-8; PMID:21278748; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cramm M, Schmitz M, Karch A, Mitrova E, Kuhn F, Schroeder B, Raeber A, Varges D, Kim YS, Satoh K, et al.. Stability and reproducibility underscore utility of RT-QuIC for diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Mol Neurobiol 2016; 53:1896-904; PMID:25823511; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s12035-015-9133-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, Benseler S, Bien CG, Cellucci T, Cortese I, Dale RC, Gelfand JM, Geschiwind M, et al.. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15:391-404; PMID:26906964; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00401-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hayashi Y, Inuzuka T. A multidisciplinary medical network approach is crucial for increasing the number of autopsies for prion disease [Reply to: How can we increase the numbers of autopsies for prion disease? A model system in Japan]. J Neurol Sci 2017; 377:95-6; PMID:28477717; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jns.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kitamoto T, Shin RW, Doh-ura K, Tomokane N, Miyazono M, Muramoto T, Tateishi J. Abnormal isoform of prion proteins accumulates in the synaptic structures of the central nervous system in patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Am J Pathol 1992; 140:1285-94; PMID:1351366 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Iwasaki Y, Hashizume Y, Yoshida M, Kitamoto T, Sobue G. Neuropathological characteristics of brainstem lesions in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Acta Neuropathol 2005; 109:557-66; PMID:15933870; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00401-005-0981-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Iwasaki Y, Mimuro M, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y, Kitamoto T, Sobue G. Clinicopathologic characteristics of five autopsied cases of dura mater-associated Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neuropathology 2008; 28:51-61; PMID:18181835; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00847.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hayashi Y, Iwasaki Y, Takekoshi A, Yoshikura N, Asano T, Mimuro M, Kimura A, Satoh K, Kitamoto T, Yoshida M, et al.. An autopsy-verified case of FTLD-TDP type A with upper motor neuron disease mimicking MM2-thalamic-type sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Prion 2016; 10:492-501; PMID:27929803; https://doi.org/ 10.1080/19336896.2016.1243192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Foutz A, Appleby BS, Hamlin C, Liu X, Yang S, Cohen Y, Chen W, Blevins J, Wang H, Gambetti P, et al.. Diagnostic and prognostic value of human prion detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Ann Neurol 2017; 81:79-92; PMID:27893164; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ana.24833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hayashi Y, Inuzuka T. Reply to: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with frontotemporal dementia (ALS-FTD) syndrome as a phenotype of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD)? A case report. J Neurol Sci 2017; 375:489; PMID:28258726; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jns.2017.02.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]