ABSTRACT

In most human and animal prion diseases the abnormal disease-associated prion protein (PrPSc) is deposited as non-amyloid aggregates in CNS, spleen and lymphoid organs. In contrast, in humans and transgenic mice with PrP mutations which cause expression of PrP lacking a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor, most PrPSc is in the amyloid form. In transgenic mice expressing only anchorless PrP (tg anchorless), PrPSc is deposited not only in CNS and lymphoid tissues, but also in extraneural tissues including heart, brown fat, white fat, and colon. In the present paper, we report ultrastructural studies of amyloid PrPSc deposition in extraneural tissues of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice. Amyloid PrPSc fibrils identified by immunogold-labeling were visible at high magnification in interstitial regions and around blood vessels of heart, brown fat, white fat, colon, and lymphoid tissues. PrPSc amyloid was located on and outside the plasma membranes of adipocytes in brown fat and cardiomyocytes, and appeared to invaginate and disrupt the plasma membranes of these cell types, suggesting cellular damage. In contrast, no cellular damage was apparent near PrPSc associated with macrophages in lymphoid tissues and colon, with enteric neuronal ganglion cells in colon or with adipocytes in white fat. PrPSc localized in macrophage phagolysosomes lacked discernable fibrils and might be undergoing degradation. Furthermore, in contrast to wild-type mice expressing GPI-anchored PrP, in lymphoid tissues of tg anchorless mice, PrPSc was not associated with follicular dendritic cells (FDC), and FDC did not display typical prion-associated pathogenic changes.

KEYWORDS: Alzheimer disease, amyloid, brown fat, basement membrane, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, CAA, colon, follicular dendritic cells, glycosylphosphatidylinositol, glycosaminoglycan, heart, lymphoid tissues, macrophages, prion protein, spleen, transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, white fat

Introduction

Amyloid is a protein aggregate composed of insoluble fibrils 8–10 nm in diameter which accumulates mainly in extracellular spaces in tissues in various diseases. Amyloid is usually formed into large plaque-like deposits which are resistant to catabolism and can lead to cellular damage and organ failure. In humans, 36 unrelated proteins or peptides have been found to generate fibrillar amyloid deposits in vivo.1 Amyloid deposits occur in many visceral organs, blood vessels and connective tissues,2 and also within the central nervous system (CNS). The association of Aβ amyloid with Alzheimer disease (AD) is well-known.3 Similarly prion protein amyloid in brain has been noted in certain animal prion diseases4-6 and in humans with Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS), variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), iatrogenic CJD, kuru, and less commonly in sporadic CJD.7-9 In AD and prion diseases, as well as in several rare familial diseases, amyloid deposition occurs within and around blood vessel walls, a condition known as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA).10 Significant evidence suggests that CAA can contribute to brain damage by mechanisms involving ischemia, microhemorrhages and disruption of normal protein elimination homeostasis.11

In human prion diseases CAA has been seen in several cases where patients expressed a mutant prion protein (PrP) with a stop codon replacing the usual amino acid codon, i.e. Y145X,12 Y163X13 or Y226X.14 These mutations result in the synthesis of PrP lacking the usual C-terminal glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor moiety. Because of the lack of the usual GPI anchor, these anchorless PrP molecules are minimally glycosylated and are not retained at the plasma membrane, but are instead secreted by the cell. This altered glycosylation and lack of membrane attachment may contribute to the tendency of these mutant PrPC proteins to form amyloid PrPSc after scrapie infection.

PrP lacking a GPI anchor is also produced in normal individuals by shedding of PrPC from cell surfaces after cleavage with the enzyme ADAM10. Interestingly, scrapie infection of conditional mutant mice lacking ADAM10 in neurons resulted in a faster disease tempo, apparently due to higher cellular amounts of PrPC and increase of PrPSc.15 It is unclear whether the shed forms of PrPC or PrPSc have additional biological effects; however, one group suggested that shed PrPSc might promote spread of pathology throughout the brain.16 To study the effect of PrP anchoring on prion disease, we previously generated transgenic mice expressing only the anchorless version of PrP (tg anchorless).17 After infection with mouse-adapted scrapie, tg anchorless mice developed a fatal disease with a slower tempo than mice expressing anchored PrP. In these studies, abundant amyloid PrPSc was found in the CNS of these mice, and amyloid PrPSc was mostly deposited in the walls and surrounding neuropil of small blood vessels including capillaries, arteries and veins. In addition, ultrastructural studies of brain of infected tg anchorless mice revealed degenerated and dystrophic myelinated axons, dystrophic neurites and neuritic and glial swelling, but not the membrane abnormalities characteristic of scrapie infection in mice with anchored PrP.18,19 Thus the CNS pathology and pathogenesis of scrapie-induced disease was markedly influenced by the presence or absence of PrP plasma membrane anchoring in the host.

In peripheral tissues, scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice showed PrPSc amyloid deposits in heart, colon, brown fat, white fat, skeletal muscle and tongue.20 Clinical evidence for restrictive cardiomyopathy was found by physiological studies.21 In the present study, we performed light microscopic and ultrastructural studies of scrapie infection in heart, brown fat, white fat, colon, spleen and lymph node in an attempt to find other evidence for possible tissue damage related to deposition of PrPSc amyloid. In all 6 tissues, extensive amyloid accumulated in the interstitial spaces between cells and occasionally also around blood vessels and within macrophages. In extraneural tissues, PrPSc amyloid was not predominantly associated with endothelial cell basement membranes, as was seen previously in the CNS. However, PrPSc amyloid did appear to invaginate and damage the plasma membrane in myocytes in heart and adipocytes in brown fat. This effect was not noted in lymphoid tissues, white fat or lamina propria of colon.

Results

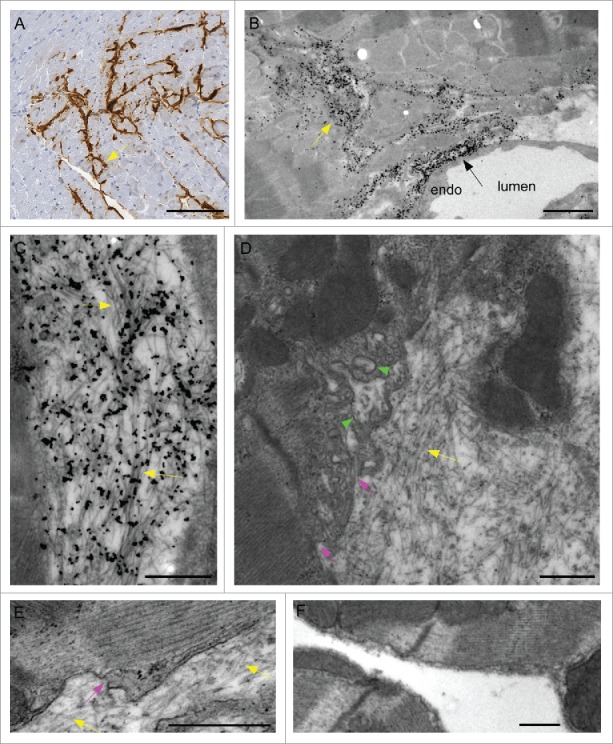

Ultrastructural studies of heart in scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice

In previous light microscopy studies of heart tissue of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice, we observed PrPSc amyloid near cardiomyocytes in most cardiac regions.21 Deposition of PrPSc was also found by other groups in cardiac tissue of chronic wasting disease-infected cervids,22 as well as in a single bovine spongiform encephalopathy-infected macaque23 and a single human CJD patient.24 In the present study, in tg anchorless mice, PrPSc was detected by light microscopy in the extracellular space between myocytes and along capillaries (Fig. 1A). Using electron microscopy with immunogold labeling, PrPSc was not detected within myocytes (Fig. 1B), but PrPSc was found within the interstitium and near vascular endothelial cells on the ablumenal side of blood vessels (Fig. 1B). Prominent foci of immunogold labeling for PrPSc were generally found to coincide with large tangles of amyloid fibrils (Fig. 1C). In non-immunolabeled sections, where membranes were more distinct, dense accumulations of fibrils were found along the myocyte plasmalemma, and individual and small bundles of fibrils were associated with invaginations in the plasma membrane and inclusions (Fig. 1D and 1E). Similar invaginations and inclusions were not seen in uninfected mice (Fig. 1F). These results were consistent with possible damage to cardiomyocytes. In addition, they may in part account for our previous evidence for signs of restrictive cardiomyopathy using physiologic tests in this scrapie amyloid mouse model.21

Figure 1.

Detection of amyloid PrPSc in heart tissue of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice. (A) IHC staining with Mab D13 shows PrPSc (brown) deposited around capillaries and in interstitial areas of myocardium (arrow). Most PrPSc appeared to be outside cardiomyocytes. (B) Low power electron micrograph shows PrPSc outside capillary endothelium (black arrow) and within interstitial areas between cardiomyocytes (yellow arrow) immunogold-labeled with anti-PrP antibody 1A8. (C) At high magnification aggregates of immunogold-labeled PrPSc amyloid fibrils (yellow arrows) were seen outside cardiomyocytes. (D) Using uranyl acetate-lead citrate (UALC) staining without etching for immunogold staining to better visualize membranes, PrPSc amyloid fibrils (yellow arrow) were observed outside myocytes adjacent to plasma membrane which had an irregular indented appearance (pink arrows) near fibrils. Occasional apparent inclusions were seen within cytoplasm near these areas (green arrowheads), however, these are likely to be extracellular invaginations sectioned across the direction of penetration. (E) Higher magnification of an area of disturbed plasma membrane (pink arrow) near extracellular amyloid fibrils (yellow arrows). Note undisturbed plasma membrane on the right half of photo. Myofibrils within cell are visible. (F) Uninfected heart stained with UALC has no amyloid fibrils in the extracellular space, and does not show plasma membrane invaginations or inclusions. Scale bars are as follows: A, 100 µm; B, 2 µm; C, D & E&F, 0.5 µm.

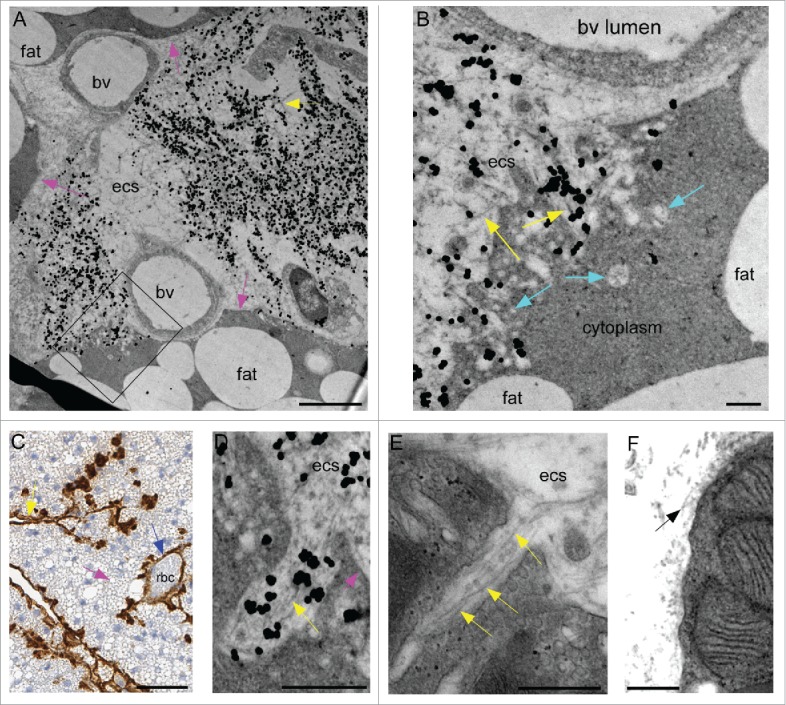

Ultrastructural studies of brown fat and white fat in scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice

In a previous study using scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice, abundant scrapie infectivity and PrPSc was noted in brown fat tissue.20 In the current study, by light microscopy in brown fat, PrPSc was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) along the connective tissue separating the lobules of fat cells and also penetrated between individual adipocytes in numerous places. PrPSc sometimes surrounded blood vessels present in the interstitial regions between the lobules (Fig. 2C, blue arrow). At the ultrastructural level, more details of this process were visible. Immunogold-labeled PrPSc could be found in large amounts in interstitial areas adjacent to blood vessels and collagen bundles and at the plasmalemma of adipocytes forming the boundary of lobules (Fig. 2A). In addition, fibrils near the adipocytes appeared to invaginate the plasma membrane from the extracellular space (Fig. 2B, D, E), however similar invaginations were not seen in uninfected mice (Fig. 2F). Although there appeared to be significant damage to the adipocytes in infected mice, the fat globules within the affected cells often had a normal appearance, and the brown fat was abundant suggesting no evidence for any metabolic damage to the tissue.

Figure 2.

Detection of amyloid PrPSc in brown fat tissue of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice. (A) Interstitial extracellular area of brown fat tissue with 2 blood vessels (bv) and 2 adjacent adipocytes. Abundant immunogold-labeled amyloid PrPSc is visible as small fibrils (yellow arrow), and is located in the extracellular space (ecs) outside blood vessels and between adipocytes. Rounded fat globules are located within adipocytes (fat). Some areas with intact adipocyte plasma membrane are indicated by pink arrows, whereas in other areas the plasma membrane appears disrupted (see box). Immunogold staining used R30 antibody. (B) Enlarged region shown by box in panel A shows gold-labeled fibrils apparently disrupting and invaginating outer membrane of the adipocyte (yellow arrows). Vacuolar structures of various sizes are also seen in this area of the cell (turquoise arrows). (C) IHC staining with Mab D13 shows PrPSc amyloid along edges of brown fat lobules (yellow arrows) and surrounding a blood vessel (blue arrow). Red blood cells in lumen are labeled (rbc). Various-sized fat globules can be seen inside brown fat cells (pink arrow), but plasma membranes of fat cells are not well visualized in this section. (D) High magnification of ultrastructure of immunogold-labeled PrPSc amyloid fibrils (yellow arrow) invaginating a brown fat cell. Fat cell plasma membrane is shown by pink arrow. Immunogold staining used R30 antibody. (E) UALC- stained brown fat shows fibrils penetrating a fat cell in a narrow pocket (yellow arrow). (F) Uninfected brown fat stained with UALC shows collagen fibrils (black arrow) in extracellular space but no perturbations of the plasma membrane. Scale bars are as follows: A, 2 µm; B, 0.25 µm; C, 50 µm; D, E & F, 0.5 µm.

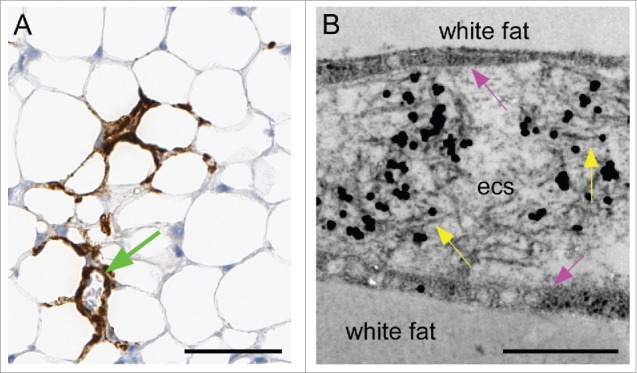

Scrapie infectivity and PrPSc was also previously detected in white fat tissue of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice.20 In the present study PrPSc was observed in white fat in a multifocal distribution. By IHC, PrPSc labeling was mostly in the interstitial space between the adipocytes (Fig. 3A). By electron microscopy, PrPSc amyloid fibrils associated with immunogold labeling were detected in the spaces between the fat cells and appeared to be outside the plasma membrane (Fig. 3B). However, the plasma membranes of fat cells were not easily discernible by this method, and thus it was unclear whether the presence of amyloid fibrils had any disruptive effect on the membrane. However, no membrane invaginations were seen similar to those noted in heart and brown fat.

Figure 3.

Detection of amyloid PrPSc in white fat tissue of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice. (A) Detection of PrPSc in interstitial areas of white fat by IHC using Mab D13. Blood vessel surrounded by PrPSc can also be seen (green arrow). (B) Ultrastructural view of interstitial region between 2 fat cells contains immunogold-labeled PrPSc fibrils (yellow arrows) in the extracellular space (ecs). The plasma membrane of the adipocytes is indicated by pink arrows, but is not seen as a sharp border in this section. Immunogold staining used R30 antibody. Scale bars are as follows: A, 50 µm; B, 0.5 µm.

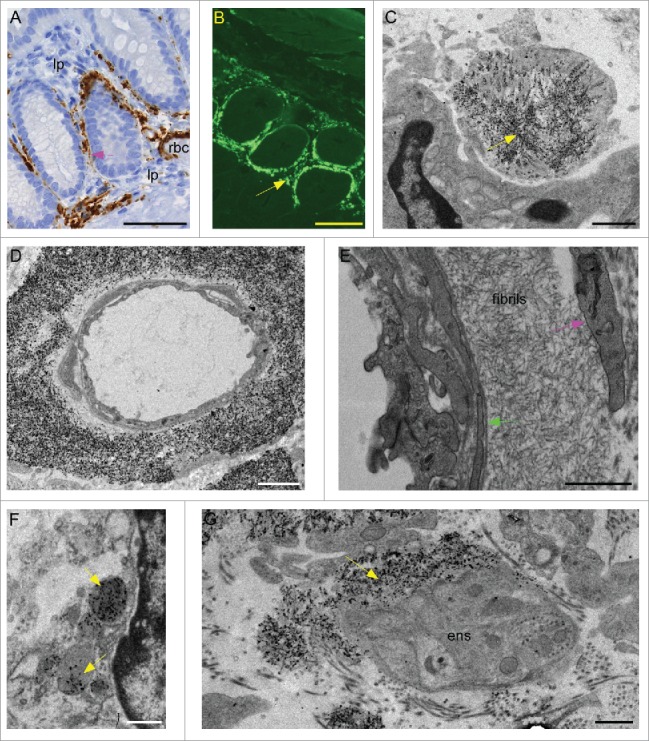

Ultrastructural studies of colon in scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice

We previously reported the presence of PrPSc detectable by IHC in the lamina propria of colon from scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice (Fig. 4A).20 This material stained strongly positive with Thioflavin S (Fig. 4B), indicating that it had an amyloid structure similar to the PrPSc found in other organs of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice. In the present study using ultrastructural analysis, abundant areas with immunogold-labeled PrPSc amyloid fibrils were detected in lamina propria sometimes associated with macrophage-like cells (Fig. 4C) and also around small blood vessels (Fig. 4D and E). However, PrPSc was usually not associated with the intestinal epithelial cell basement membrane. Within macrophages PrPSc was found both as cytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 4C) and within phagolysosomes (Fig. 4F), and was also found surrounding small groups of enteric neuronal ganglion cells (Fig. 4G). In none of these locations was there invagination or damage to the cell membranes associated with the amyloid as had previously been observed in heart and brown fat. However, there was evidence for clinical gastrointestinal signs such as abnormal stools in 20% of the mice.

Figure 4.

Detection of amyloid PrPSc in colon of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice. (A) PrPSc detected by IHC using Mab D13 in lamina propria (lp) of colon. Blood vessel with red blood cells (rbc) in lumen has abundant PrPSc in a perivascular distribution. A small amount of PrPSc staining can also be seen at inner edge of epithelial cells (pink arrow). (B) Thioflavin S staining of amyloid PrPSc in colon of tg anchorless mouse similar to mouse shown in panel A. Most amyloid was located in the lamina propria (arrow) surrounding the villi. (C) Large macrophage-like cell appears to surround a clump of immunogold-labeled PrPSc amyloid with visible fibrils (yellow arrow). Immunogold staining in panels C, D, F, and G used 1A8 antibody. (D) Capillary in lamina propria is surrounded by a thick ring of immunogold-labeled PrPSc amyloid starting near the outer surface of the endothelial cells (green arrow). (E) At higher power UALC-stained arteriole shows thick ring of PrPSc amyloid fibrils between smooth muscle basement membrane and outer smooth muscle cells (pink arrow). Note that the endothelial cell body borders the lumen and separates the lumen from the smooth muscle. (F) Immunogold-labeled PrPSc accumulated in phagolysosomes (yellow arrows) of a macrophage-like cell in the lamina propria. (G) Immunogold-labeled PrPSc amyloid (yellow arrow) partially surrounds neuronal processes in a ganglion of the enteric nervous system (ens). Scale bars are as follows: A,&B 50 µm; C, 2 µm; D, 0.5 μm; E & G, 1 µm; F, 0.5 µm.

Light microscopy and ultrastructural studies of lymphoid tissues in scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice

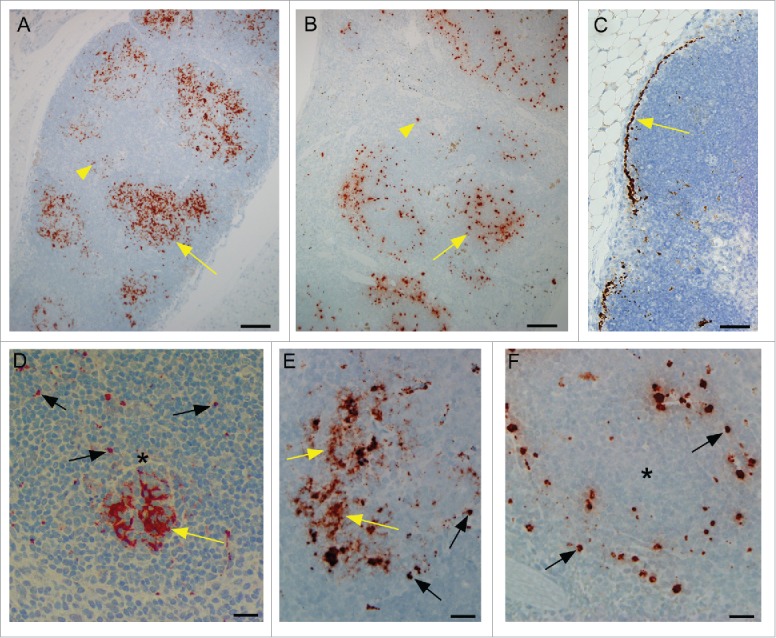

Previous papers have reported the presence of PrPres detectable by western blot in spleen of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice,21 however, no pathology or IHC studies of spleen or other lymphoid tissues have been published. In the current work using IHC with monoclonal anti-PrP antibody D13, PrPSc in C57BL mice was detected in secondary lymphoid follicles of spleen and lymph nodes (Fig. 5A). At higher magnification, in C57BL mice, PrPSc accumulated in secondary follicles, not only as small rounded deposits which were consistent with macrophages, but also in the light zones of secondary follicles as generalized finely punctuate accumulations typically associated with follicular dendritic cells (FDC) (Fig. 5A, D &E).25

Figure 5.

Detection of PrPSc by immunohistochemistry using monoclonal anti-PrP antibody D13 in lymphoid tissues of scrapie-infected C57BL and tg anchorless mice. (A) In a C57BL mouse, PrPSc is mostly located in multiple secondary follicles (arrow) in spleen. There is a small amount of staining outside of the follicles (arrowhead) and almost no detectable sub-capsular staining. (B) In a tg anchorless mouse, in spleen PrPSc staining is mostly in secondary follicles (arrow) with a small amount in red pulp (arrowhead). (C) Mesenteric lymph node in a tg anchorless mouse shows pronounced sub-capsular PrPSc (arrow). (D) At a higher magnification, a single follicle from a C57BL mouse shows dense PrPSc staining (yellow arrow) concentrated in a rounded region consistent with FDC networks found in light zones of follicles. Single dense punctate PrPSc consistent with accumulation in macrophages was also noted (black arrows). (E) In spleen follicle from another scrapie-infected C57BL mouse, PrPSc staining occurred both in small punctate accumulations (black arrows), probably macrophages, and in patchy less dense accumulations suggestive of FDCs (yellow arrows). (F) In a follicle from the scrapie-infected tg anchorless mouse shown in panel B, punctate PrPSc staining (black arrows) characteristic of macrophages was seen mostly near the edge of the follicle. However, the clustered patchy PrPSc staining characteristic of FDC was not noted. Asterisks in panels D and F indicate the approximate location of the light zone of the follicles. Scale bars: Panels A and B, 100 μm; C, 50 μm; D, E and F, 20 μm.

In tg anchorless mice lymphoid tissues, PrPSc was also detected mainly in secondary follicles (Fig. 5B), but PrPSc sometimes accumulated in sub-capsular regions of spleen and lymph node (Fig. 5C). However, in these mice, PrPSc was not found in a pattern consistent with FDC, but instead all the PrPSc was in a pattern consistent with follicular macrophages (Fig. 5F).

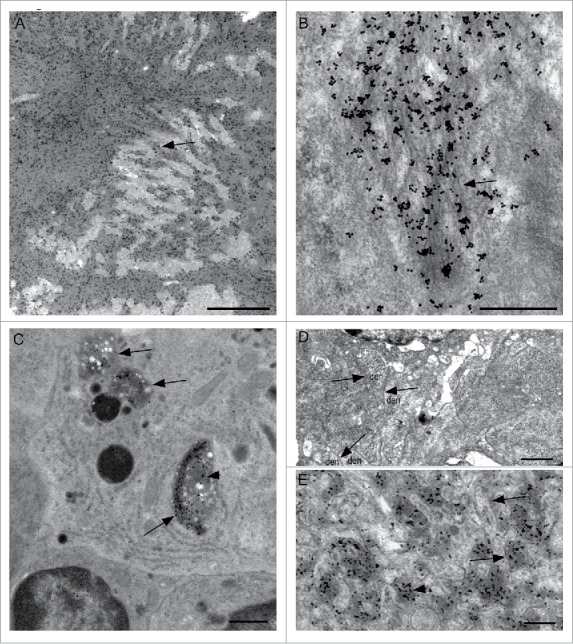

Ultrastructural studies were done to examine the details of the PrPSc accumulation in spleen and lymphoid organs. In tg anchorless mice abundant amyloid fibrils and amyloid plaques were associated with the sub-capsular and trabecular areas of spleen and lymph nodes (Fig. 6A and B). In addition, immunogold-labeled PrPSc was seen in the phagolysosomes of tingible body macrophages (TBM) within lymphoid follicles (Fig. 6C), but no amyloid fibrils were visible in this location by electron microscopy. Furthermore, PrPSc was not seen in association with dendrites of FDC (Fig. 6D), which was a prominent feature during scrapie infection in C57BL mice expressing normal GPI-anchored PrP (Fig. 6E).25,26 In summary, in lymphoid tissues, absence of GPI-anchored PrP in tg anchorless mice correlated with lack of association of PrPSc with FDC, but PrPSc was nevertheless found in macrophages and was also associated with sub-capsular lymphoid connective tissue.

Figure 6.

Ultrastructural detection of PrPSc by immunogold labeling in lymphoid tissues of scrapie-infected C57BL and tg anchorless mice. (A) Large immunogold-labeled PrPSc plaque in red pulp area of spleen from a tg anchorless mouse. (B) Higher magnification view of PrPSc plaque in a tg anchorless spleen shows immuno-gold labeling associated with amyloid fibrils (arrow). (C) Tingible body macrophage in Peyer's patch of tg anchorless mouse shows several cytoplasmic phagolysosomes (arrows) containing immunogold-labeled PrPSc (arrowhead). Two adjacent lymphocytes with round nuclei are partially visible on lower border. (D) Ultrastructural view of a follicular dendritic cell within a lymph node secondary follicle of a scrapie-infected tg anchorless mouse seen with UALC staining. FDC dendrites (den) surround the nucleus (N), however, these dendrites are not extended, and the extracellular space between dendrites is not expanded nor do they accumulate excess electron dense deposits as is typical in scrapie affected lymphoreticular tissues. Arrows point to the apposed membranes of adjacent dendrites. At the magnification shown, the extracellular space lying between apposed membranes of adjacent dendrites is not visible. No PrPSc was detected in associated with these FDC in infected tg anchorless mice by immunogold labeling (not shown), and this result was consistent with light microscopy results (Fig. 5E). (E) In a C57BL mouse, immunogold-labeled PrPSc is located within the extracellular space surrounding hypertrophic FDC dendrites. In some places dendrite membranes are visible (arrows). Immunogold labeling for PrPSc is associated with amorphous electron dense material which lies in an expanded extracellular space between dendrites (arrowhead). Additional uninfected mice were also examined as controls. These mice did not show any of the features described here for the scrapie-infected mice. Scale bars: A, 2 μm; B, 0.5 μm; C, 1 μm; D, 1 μm, E, 0.3 μm.

Discussion

In our previous experiments using light microscopy to study scrapie infection in transgenic mice expressing anchorless PrP, PrPSc amyloid deposition was detected in several sites outside the CNS, including heart, colon, brown fat, white fat, tongue, skeletal muscle and lymphoid tissues.20 In these earlier experiments, there was no evidence of cellular loss, however, in the present ultrastructural studies, evidence for possible cellular damage by amyloid fibrils was observed. PrPSc amyloid fibrils were clustered on the outside of myocytes in heart and adipocytes in brown fat, and appeared to perturb the usual smooth plasma membrane surface. Fibrils were seen in deep pockets in the plasma membrane which appeared to invaginate the cells (Figs. 1D, E, 2B, D, E). The areas with such unusual changes are likely to result in cellular dysfunction. These cells might be attempting to internalize or phagocytose the fibrils or alternatively might be growing around the fibrils. In the case of heart tissue, previous studies found impaired cardiac function in these mice,21 and the ultrastructural observations reported here might have contributed to this dysfunction. In brown fat, no definitive clinical effect was associated with the damage of adipocytes which we observed.

In lymphoid tissues, white fat, and colon, PrPSc amyloid fibrils detected in interstitial regions did not appear to invaginate the cells of scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice. In lymphoid organs, PrPSc was detected in phagolysosomes of macrophages, but there was no evidence for infection of FDC (Fig. 5D and E). Furthermore, specific FDC membrane hyperplasia associated with excess trapping of PrPSc and immune complexes in animals expressing GPI-anchored PrP was absent.25,26 In white fat, the PrPSc fibrils were located outside the adipocytes, but did not damage the adjacent plasma membrane. In colon, PrPSc amyloid accumulated near enteric neuronal ganglion cells in lamina propria, but no damage to plasma membrane was detected. In addition, PrPSc was associated with macrophages located in the lamina propria of colon, but macrophages did not show invagination of plasma membrane by fibrils. However, macrophages did appear to surround and engulf large clusters of fibrils, and PrPSc was also occasionally detected in phagolysosomes of these cells. In both lymphoid tissues and colon, PrPSc detected within phagolysosomes of macrophages lacked fibrillar structures detectable by electron microscopy, suggesting that PrPSc fibrils might be catabolized within macrophage phagolysosomes.

The mechanism of spread of PrPSc amyloid to extraneural tissue sites in tg anchorless mice is not entirely clear. In previous experiments, infectivity was detectable in blood after intraperitoneal scrapie injection.20 Furthermore, after intraperitoneal or intravenous injection, PrPSc was found by immunoblot or IHC starting at 149 dpi in colon, heart, brown fat and other extraneural tissues, suggesting that hematogenous or lymphatic spread to these tissues was rather efficient.27 In contrast, in these same experiments, spread by intraperitoneal and intravenous routes to the CNS was very inefficient and was detected only at late time-points in a few mice. The explanation for the poor CNS infection appeared to be related to the combination of lack of infection of FDC in spleen and lymph node, very slow neuronal transport of infectivity and inability of infectivity to cross the blood-brain barrier in tg anchorless mice.

In our studies of scrapie infection of extraneural tissues in tg anchorless mice, there appeared to be a strong selectivity against amyloid deposition at certain tissue sites. This was surprising since PrP is expressed in most tissues and cell types.28,29 The lamina propria of colon was a favored site for deposition of amyloid PrPSc, whereas other tissue layers of colon and all layers of other gastrointestinal tract levels were mostly negative. Similarly, the plasma membrane of cardiomyocytes and interstitium of heart was a preferred site for PrPSc amyloid deposition, but interstitium of lung and kidney was negative.

In contrast to the above findings in certain visceral organs, we previously found that PrPSc amyloid in the CNS was primarily located around small blood vessels where amyloid deposition appeared to begin at the endothelial cell basement membranes.18 To explain this process we speculated that brain endothelial basement membranes might provide biochemical structures forming a scaffold capable of binding small oligomers of PrPSc and initiating their assembly into larger polymers.30 These polymers in turn might be able to self-scaffold to mediate further polymerization to account for the spread of the PrPSc amyloid radially away from the blood vessel and into the CNS parenchyma. In contrast, in visceral tissues such as heart, colon and brown fat, PrPSc amyloid was consistently found in interstitial areas, and perivascular amyloid was less prominent than in brain. The specificity of the amyloid scaffolding process might also be an explanation for these differences, and for the lack of amyloid deposition in some other visceral organs as noted above. In visceral tissues, PrPSc amyloid might be deposited in interstitial areas secondary to scaffolding by structures other than endothelial basement membranes. Scaffolding structures might be tissue-specific cell surface components of fibrocytes, macrophages, adipocytes or cardiomyocytes, resulting in amyloid deposition in the interstitial regions of certain organs.

The neuropathology with prominent CAA described in scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice has also been noted in 3 cases of human familial prion disease associated with expression of anchorless PrP. These independent cases were found to express a mutant PrP which gave a stop codon at residue 14512, residue 16313 or residue 226.14 Pathology for tissue outside the CNS was available only for the patient with the Y163X mutation. In several patients from this same family, amyloid PrPSc was seen in heart, colon, peripheral nerves, spleen and lymphoid tissues, similar to our mouse studies. However, PrPSc amyloid was also noted in lung and kidney of these patients, and these organs were negative in our tg mice expressing anchorless PrP. Clinical signs related to some of these PrPSc deposition sites in patients with Y163X included chronic diarrhea, urinary retention, and postural hypotension, but no cardiac signs were noted. In contrast, in scrapie-infected tg anchorless mice cardiac signs and urinary retention were both prominent, but the only gastrointestinal signs were soft stools observed in about 20% of mice and no diarrhea was seen. This discrepancy with the Y163X human patients might be due to either less widespread amyloid in colon of tg anchorless mice or to physiological differences in mouse versus human colon. In summary, there were both similarities and differences in the disease seen in humans with PrP Y163X compared with tg anchorless mice. These differences might be ascribed to many factors including human vs. mouse PrP sequence differences, lack of nearly the entire C-terminal half of the mutant human PrP, and lack of transmissible prions in the human patient.13,20

The widespread and abundant deposition of extraneural PrPSc amyloid in mice and humans expressing anchorless PrP is in marked contrast to the more limited deposition of extraneural deposition of amyloid and non-amyloid PrPSc in other prion diseases of humans and animals. Both anchored and anchorless PrP are widely expressed in many cell types, and thus restricted expression of PrP is not likely to explain the presence and distribution of extraneural amyloid. However, the minimal amount of glycosylation and lack of a GPI anchor moiety in anchorless PrP are both factors which might favor the formation of amyloid due to lack of membrane attachment and reduced hydrophilicity.18 This might explain the strong tendency to form amyloid PrPSc in humans and mice expressing anchorless PrP.

Methods

Mice, scrapie infections and tissue collection

Ethics statement: All mice were housed at the Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML) in an AAALAC-accredited facility, and research protocols and experimentation were approved by the NIH RML Animal Care and Use Committee.

Generation of transgenic mice expressing GPI-anchorless PrP (tg anchorless) on a C57BL/10 genetic background was described previously.17 Tg anchorless mouse lines 44 and 23 were previously found to have similar PrP expression levels in brain and were similar in disease tempo, clinical signs and brain pathology by light and electron microscopy after infection with scrapie strains 22L and RML.18 In the present ultrastructural study tg anchorless mice from both lines were examined, and results were similar in all extraneural tissues studied.

Five to 8 week old mice were inoculated either intracerebrally (IC) with 50 µl of a 1% scrapie brain homogenate. Both strains 22L and RML were used, and results were similar with both strains. Animals were observed daily for onset and progression of scrapie. Scrapie-infected mice were killed when mice developed advanced clinical signs consistent with scrapie infection which required euthanasia. Homozygous tg anchorless mice were used 325–411 dpi, and heterozygous mice were used at 559–688 dpi. Tissues from 6 infected and 4 uninfected, age-matched tg anchorless mice were studied in these experiments. Two scrapie-infected C57BL/10 mice killed at 155–161 dpi were also studied in these experiments for comparisons to infected tg anchorless mice.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Mice were killed and brains were placed in 3.7% phosphate-buffered formalin for 3 to 5 d before dehydration and embedding in paraffin. Serial 5-µm sections were cut using a standard Leica microtome, placed on positively charged glass slides, and air-dried overnight at room temperature. The following day slides were heated in an oven at 60°C for 20–30 min. For PrPSc detection, antigen retrieval was achieved using extended cell conditioning with CC1 buffer (Ventana) containing Tris-Borate-EDTA, pH 8.0 for 100 minutes at 100°C. Immunohistochemical staining for PrP used a standard avidin-biotin complex immunoperoxidase protocol using anti-PrP antibody D13 (In-Pro Biotechnology, South San Francisco, CA) at a dilution of 1:500 for 2 hours. Biotinylated goat anti-human IgG (Cat# 109–065–097 Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA) was used at a 1:250 dilution as the secondary antibody. This was followed by Ventana streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase with Fast Red chromogen or streptavidin-peroxidase with amino ethyl carbazol or 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as chromogens (Ventana, Tucson, AZ) with hematoxylin counterstain. All histopathology slides for light microscopy were read using an Olympus BX51 microscope, and images were obtained using Microsuite FIVE software.

Perfusion and processing for electron microscopy

Mice were perfused with fixative containing 3% paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Excised tissues were then immersed in this fixative and held overnight at 4°C. Tissue pieces were processed further using a Lynx® automated tissue processor with agitation at 20°C unless otherwise indicated: one wash in PBS for 3 hr, one wash in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.2 for 4 hr, post-fix in 2% osmium tetroxide in phosphate buffer for 6 hr, one wash in phosphate buffer for 3 hr, 3 washes in water for 3 hr each, in-block staining with 1% uranyl acetate in water for 6 hr, 3 washes in water for 3 hr each, dehydration in 70%, 100%, and 100% acetone at 10°C for 3 hr each, and infiltration at 20°C in Araldite resin (Structure Probe, Inc., West Chester, PA) at 50% for 8 hr, 75% for 12 hr, and 2 changes of 100% for 20 hr each. Some tissue blocks were processed using a Leica EM TP processor using the procedure above with the omission of the uranyl acetate. Tissue blocks were then transferred to fresh resin in molds and polymerized at 65°C for 24 to 48 hr.

Immunolabeling for electron microscopy

Immunolabeling was performed by 2 different laboratories, APHA, Lasswade Laboratory in the UK and at Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML) in the United States. There were some minor differences in reagents and counterstaining methods described below. For routine electron microscopy sections were stained with 10% uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate (UALC) or 1% uranyl acetate alone. These stains were used to give better definition of cellular structure and better definition of membranes than can be obtained on sections which are treated with formic acid for enhancement of immunolabeling (see below).

For ultrastructural immunohistochemistry, serial 65 nm sections were taken. The 65 nm sections were placed on 600 mesh gold grids and etched in saturated sodium periodate for 60 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked and sections de-osmicated with 6% hydrogen peroxide in water for 10 minutes followed by enhancement of antigen expression with neat (98%) formic acid for 10 minutes. Residual aldehyde groups were quenched with 0.2 M glycine in PBS, pH 7.4 for 3 minutes. Preimmune serum or anti-PrP primary antibody 1A831 or R3032 at a 1:500 or 1:1500 dilution respectively in incubation buffer, were then applied for 15 hours. After rinsing extensively, sections were incubated with Aurion UltraSmall GAR-gold (0.6 nm) conjugate (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) (RML) or British Biocell International GAR- IgG gold (Agar Scientific Ltd, Essex, United Kingdom) (APHA). Sections were then post-fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS and labeling was enhanced to enlarge the gold with Goldenhance (Universal Biologicals, Cambridge, UK) for 10 minutes or Gold Enhance (Nanoprobes, Inc. Yaphank, NY) according to manufacturer's recommendations. Grids were counterstained with UALC in the UK and with 1% uranyl acetate at RML.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AAALAC

Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- APHA

Animal and Plant Health Agency

- Aβ

amyloid β

- CAA

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- CJD

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- CNS

central nervous system

- DAB

3,3′-diaminobenzidine

- dpi

days post inoculation

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- ens

enteric nervous system

- FDC

follicular dendritic cell

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- GSS

Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker

- IC

intracerebral

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- NIAID

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PrP

prion protein

- PrPSc

prion disease associated prion protein

- rbc

red blood cell

- RML

Rocky Mountain Laboratory

- TBM

tingible body macrophage

- tg anchorless

transgenic mice expressing GPI-anchorless mouse PrP

- UALC

uranyl acetate and lead citrate

- UK

United Kingdom

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jim Striebel, Jay Carroll, Katie Phillips and Robert Faris for critical review of the manuscript, Nancy Kurtz and Lori Lubke for assistance with histology preparation, Kimberly Meade-White for technical assistance, and Jeff Severson and Ed Schreckendgust for animal husbandry.

FUNDING

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID.

REFERENCES

- [1].Sipe JD, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Ikeda SI, Merlini G, Saraiva MJ, Westermark P. Amyloid fibril proteins and amyloidosis: Chemical identification and clinical classification International Society of Amyloidosis 2016 Nomenclature Guidelines. Amyloid 2016; 23:209-13; PMID:27884064; https://doi.org/ 10.1080/13506129.2016.1257986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pepys MB. Amyloidosis. Annu Rev Med 2006; 57:223-41; PMID:16409147; https://doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: Genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev 2001; 81:741-66; PMID:11274343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bruce ME, Dickinson AG. Genetic control of amyloid plaque production and incubation period in scrapie-infected mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1985; 44:285-94; PMID:3921669; https://doi.org/ 10.1097/00005072-198505000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jeffrey M, Goodsir CM, Holliman A, Higgins RJ, Bruce ME, McBride PA, Fraser JR. Determination of the frequency and distribution of vascular and parenchymal amyloid with polyclonal and N-terminal-specific PrP antibodies in scrapie-affected sheep and mice. Vet Rec 1998; 142:534-7; PMID:9637378; https://doi.org/ 10.1136/vr.142.20.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liberski PP, Guiroy DC, Williams ES, Walis A, Budka H. Deposition patterns of disease-associated prion protein in captive mule deer brains with chronic wasting disease. Acta Neuropathol 2001; 102:496-500; PMID:11699564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ghetti B, Piccardo P, Frangione B, Bugiani O, Giaccone G, Young K, Prelli F, Farlow MR, Dlouhy SR, Tagliavini F. Prion protein amyloidosis. Brain Pathol 1996; 6:127-45; PMID:8737929; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Budka H, Aguzzi A, Brown P, Brucher JM, Bugiani O, Gullotta F, Haltia M, Hauw JJ, Ironside JW, Jellinger K, et al.. Neuropathological diagnostic criteria for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and other human spongiform encephalopathies (prion diseases). Brain Pathol 1995; 5:459-66; PMID:8974629; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1995.tb00625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ironside JW. Review: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain Pathol 1996; 6:379-88; PMID:8944311; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00869.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Revesz T, Holton JL, Lashley T, Plant G, Frangione B, Rostagno A, Ghiso J. Genetics and molecular pathogenesis of sporadic and hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathies. Acta Neuropathol 2009; 118:115-30; PMID:19225789; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00401-009-0501-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Carare RO, Hawkes CA, Jeffrey M, Kalaria RN, Weller RO. Review: cerebral amyloid angiopathy, prion angiopathy, CADASIL and the spectrum of protein elimination failure angiopathies (PEFA) in neurodegenerative disease with a focus on therapy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2013; 39:593-611; PMID:23489283; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/nan.12042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ghetti B, Piccardo P, Spillantini MG, Ichimiya Y, Porro M, Perini F, Kitamoto T, Tateishi J, Seiler C, Frangione B, et al.. Vascular variant of prion protein cerebral amyloidosis with tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles: The phenotype of the stop codon 145 mutation in PRNP. Proc Nati Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93:744-8; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.93.2.744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mead S, Gandhi S, Beck J, Caine D, Gallujipali D, Carswell C, Hyare H, Joiner S, Ayling H, Lashley T, et al.. A novel prion disease associated with diarrhea and autonomic neuropathy. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1904-14; PMID:24224623; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1214747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jansen C, Parchi P, Capellari S, Vermeij AJ, Corrado P, Baas F, Strammiello R, van Gool WA, van Swieten JC, Rozemuller AJ. Prion protein amyloidosis with divergent phenotype associated with two novel nonsense mutations in PRNP. Acta Neuropathol 2010; 119:189-97; PMID:19911184; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00401-009-0609-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Altmeppen HC, Prox J, Krasemann S, Puig B, Kruszewski K, Dohler F, Bernreuther C, Hoxha A, Linsenmeier L, Sikorska B, et al.. The sheddase ADAM10 is a potent modulator of prion disease. ELife 2015; 4:e04260; PMID:25654651; https://doi.org/ 10.7554/eLife.04260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Glatzel M, Linsenmeier L, Dohler F, Krasemann S, Puig B, Altmeppen HC. Shedding light on prion disease. Prion 2015; 9:244-56; PMID:26186508; https://doi.org/ 10.1080/19336896.2015.1065371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chesebro B, Trifilo M, Race R, Meade-White K, Teng C, LaCasse R, Raymond L, Favara C, Baron G, Priola S, et al.. Anchorless prion protein results in infectious amyloid disease without clinical scrapie. Science 2005; 308:1435-9; PMID:15933194; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1110837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chesebro B, Race B, Meade-White K, Lacasse R, Race R, Klingeborn M, Striebel J, Dorward D, McGovern G, Jeffrey M. Fatal transmissible amyloid encephalopathy: A new type of prion disease associated with lack of prion protein membrane anchoring. PLoS Pathog 2010; 6:e1000800; PMID:20221436; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jeffrey M, McGovern G, Siso S, Gonzalez L. Cellular and sub-cellular pathology of animal prion diseases: Relationship between morphological changes, accumulation of abnormal prion protein and clinical disease. Acta Neuropathol 2011; 121:113-34; PMID:20532540; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00401-010-0700-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Race B, Meade-White K, Oldstone MB, Race R, Chesebro B. Detection of prion infectivity in fat tissues of scrapie-infected mice. PLoS Pathog 2008; 4:e1000232; PMID:19057664; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Trifilo MJ, Yajima T, Gu YS, Dalton N, Peterson KL, Race RE, Meade-White K, Portis JL, Masliah E, Knowlton KU, et al.. Prion-induced amyloid heart disease with high blood infectivity in transgenic mice. Science 2006; 313:94-7; PMID:16825571; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1128635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jewell JE, Brown J, Kreeger T, Williams ES. Prion protein in cardiac muscle of elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) infected with chronic wasting disease. J Gen Virol 2006; 87:3443-50; PMID:17030881; https://doi.org/ 10.1099/vir.0.81777-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Krasemann S, Mearini G, Kramer E, Wagenfuhr K, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Neumann M, Bodemer W, Kaup FJ, Beekes M, Carrier L, et al.. BSE-associated prion-amyloid cardiomyopathy in primates. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:985-8; PMID:23735198; https://doi.org/ 10.3201/eid1906.120906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ashwath ML, Dearmond SJ, Culclasure T. Prion-associated dilated cardiomyopathy. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:338-40; PMID:15710800; https://doi.org/ 10.1001/archinte.165.3.338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jeffrey M, McGovern G, Goodsir CM, Brown KL, Bruce ME. Sites of prion protein accumulation in scrapie-infected mouse spleen revealed by immuno-electron microscopy. J Pathol 2000; 191:323-32; PMID:10878556; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/1096-9896(200007)191:3%3c323::AID-PATH629%3e3.0.CO;2-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McGovern G, Jeffrey M. Scrapie-specific pathology of sheep lymphoid tissues. PloS One 2007; 2:e1304; PMID:18074028; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0001304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Klingeborn M, Race B, Meade-White KD, Rosenke R, Striebel JF, Chesebro B. Crucial role for prion protein membrane anchoring in the neuroinvasion and neural spread of prion infection. J Virol 2011; 85:1484-94; PMID:21123371; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.02167-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bendheim PE, Brown HR, Rudelli RD, Scala LJ, Goller NL, Wen GY, Kascsak RJ, Cashman NR, Bolton DC. Nearly ubiquitous tissue distribution of the scrapie agent precursor protein. Neurology 1992; 42:149-56; PMID:1346470; https://doi.org/ 10.1212/WNL.42.1.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ford MJ, Burton LJ, Morris RJ, Hall SM. Selective expression of prion protein in peripheral tissues of the adult mouse. Neuroscience 2002; 113:177-92; PMID:12123696; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00155-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rangel A, Race B, Klingeborn M, Striebel J, Chesebro B. Unusual cerebral vascular prion protein amyloid distribution in scrapie-infected transgenic mice expressing anchorless prion protein. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2013; 1:25-36; PMID:24252347; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/2051-5960-1-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jeffrey M, Goodsir CM, Fowler N, Hope J, Bruce ME, McBride PA. Ultrastructural immuno-localization of synthetic prion protein peptide antibodies in 87V murine scrapie. Neurodegeneration 1996; 5:101-9; PMID:8731389; https://doi.org/ 10.1006/neur.1996.0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Caughey B, Raymond GJ, Ernst D, Race RE. N-terminal truncation of the scrapie-associated form of PrP by lysosomal protease(s): Implications regarding the site of conversion of PrP to the protease-resistant state. J Virol 1991; 65:6597-603; PMID:1682507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]