Abstract

Background and Objectives

Social exclusion is ubiquitous and painful. Evolutionary models indicate sex differences in coping with social stress. Recent empirical data suggest different sex patterns in hypothalamic– pituitary–adrenal (HPA) and sympathetic–adrenal–medullary (SAM) reactivity. The present study sought to test this hypothesis.

Design

We examined differences in endocrine and emotional response to exclusion by using a virtual ball tossing paradigm (Cyberball). Saliva samples and mood ratings were collected to reflect levels before, and repeatedly following, exclusion.

Methods

The sample included 21 women and 23 men. Cortisol and salivary alpha amylase (sAA), biomarkers of the HPA and SAM systems, respectively, were used as indices of two arms of stress response.

Results

Following exclusion, all participants experienced mood worsening followed by mood improvement, with men reporting less distress than women. Women evinced decline in cortisol following the Cyberball task, whereas men’s cortisol levels showed a non-significant rise, and then decline, following exclusion.

Conclusions

Our results concur with previous findings showing SAM reactivity to be gender-neutral and HPA reactivity to be gender-divergent. Additional studies are needed to examine sex-specific response to social exclusion. Implications for individual differences in recovery from stress are discussed.

Keywords: Sex-selection, hormones, stress, sex, gender

The needs to belong to a social group and to advance in its hierarchy are central social motives across species, with psychological and physiological systems suggested to constantly monitor our place in the social structure. These needs lead to a mobilization of a host of cognitive, neurological, motivational, and behavioral subsystems when our place in this structure is threatened (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Sapolsky, 2005). Exclusion has evinced being a powerful stressor, undermining one’s place within a social structure. Indeed, social exclusion and ostracism may be used as a competitive tactic by females, but not males, who use more individualistic tactics to establish group hierarchy (Benenson, Antonellis, Cotton, Noddin, & Campbell, 2008; Benenson, Hodgson, Heath, & Welch, 2008). Still, it is a ubiquitously stressful experience: the ensuing insecurity about one’s social position engenders significant self-reported distress (Zadro, Williams, & Richardson, 2004), changes in behavior (Oaten, Williams, Jones, & Zadro, 2008), neural activity (Crowley, Wu, Molfese, & Mayes, 2010), and endocrine activity (e.g., Zöller, Maroof, Weik, & Deinzer, 2010).

The two main components of the physiological stress response are the hypothalamic–pituitary– adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic–adrenal–medullary (SAM) branch of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) (Stratakis & Chrousos, 1995). The HPA axis is a major component of the neuro-endocrine system, and is of special interest in reactivity to stress. HPA activation begins when a stressor triggers a cascade of hormones, ultimately resulting in the release of cortisol from the adrenal cortex. Cortisol interacts with the ANS to prepare the body to respond efficiently to a stressor with a fight-or-flight response (e.g., Sapolsky, 2004).

Basal salivary cortisol level has been shown to reflect chronic stress (Goenjian et al., 2003; Lindley, Carlson, & Benoit, 2004; Pfeffer, Altemus, Heo, & Jiang, 2007). Social-evaluative stressors (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Stroud et al., 2009; Stroud, Tanofsky-Kraff, Wilfley, & Salovey, 2000; Wirth, Welsh, & Schultheiss, 2006) have evinced significant cortisol reactivity. However, this reactivity appears to be sex-dependent, as sex differences have emerged in studies of reactivity to exclusion (Stroud et al., 2000; Stroud, Salovey, & Epel, 2002; Zöller et al., 2010) and other social-evaluative stressors (Maestripieri, Baran, Sapienza, & Zingales, 2010; Stroud et al., 2002; Uhart, Chong, Oswald, Lin, & Wand, 2006).

Specifically, men and women’s HPA reactivity to social threat appears to follow different patterns (for a review, see Kudielka & Kirschbaum, 2005). In some studies, only women exhibited no salivary cortisol response (area under the curve and repeated measures at regular intervals) from pre- to post-exclusion in Cyberball, a virtual ball toss game (Zöller et al., 2010), while others found that excluded women, but not men, showed blunted salivary cortisol response to a later public speaking task (Weik, Maroof, Zöller, & Deinzer, 2010). In a recent study, a change in salivary cortisol following exclusion in a virtual ball toss game was not found for women or men (from pre- to 33-minute-post-exclusion; Seidel et al., 2013). Importantly, this negative finding by Seidel and colleagues contrasts with their identification of significant sex differences in testosterone and progesterone reactivity. Finally, higher levels of salivary cortisol tended to be observed following social exclusion (when comparing 20 minutes post-exclusion levels only) among women with a specific hormonal profile (in the luteal phase or on oral contraceptives), when compared to conterparts included in a similar encounter (Zwolinski, 2012). In summary, sex differences in HPA response to social threat present a diverse pattern of findings. These differences may be explained by factors such as timing (immediately following the stressor, versus after a delay) and type of task (face to face vs. virtual ball toss).

With respect to SAM, an additional system which activates during times of stress as part of the ANS, findings are more consistent. This system entails physiological arousal and results in the secretion of norepinephrine from the adrenal medulla (Tsigos & Chrousos, 2002). Recently, salivary alpha amylase (sAA), an enzyme secreted by the parotid salivary gland (Zakowski & Bruns, 1985), has been incorporated as a biomarker for human SAM activation (Chatterton, Vogelsong, & Lu, 1996; although see Bosch, Veerman, de Geus, & Proctor, 2011) which is more readily accessed than norepinephrine. Basal levels of sAA have been associated with chronic psychological stress in humans (Rohleder, Chen, Wolf, & Miller, 2008; van Veen et al., 2008; Vigil, Geary, Granger, & Flinn, 2010). sAA has been also shown to index responses to several acute psychosocial stressors (Kivlighan & Granger, 2006; Stroud et al., 2009), among them social exclusion: sAA reactivity was reported in adolescents vis-à-vis gradual exclusion from a conversation with age- and sex-matched confederates (Stroud et al., 2009); however, sex differences were not examined. Thus, changes in sAA appear to index both acute and chronic social stress (for a review, see Nater & Rohleder, 2009). Importantly, these findings were consistent across sex groups (e.g., Kivlighan & Granger, 2006; van Stegeren, Wolf, & Kindt, 2008), although specifically for exclusion, little information is available.

One possible explanation for the divergence of HPA and SAM, and subjective response to social stress lies with Taylor’s theory (Taylor et al., 2000) of “tend-and-befriend” vs. “fight-or-flight” responses among women and men, respectively. This theory postulates that men and women have, over the course of evolution, adapted different coping mechanisms when facing social stressors. Specifically, while men are able to fight or flee in the face of adversity, women, who may not be able to do so when nursing, pregnant, or accompanied by offspring, turn to their peers for support and assistance. Thus, HPA suppression in women may prove adaptive in allowing these approach-oriented behaviors (van Peer et al., 2007).

Clearly, social stress induces not only endocrine, but also emotional, reactions for both men and women (Glynn, Christenfeld, & Gerin, 1999; Kirschbaum, Klauer, Filipp, & Hellhammer, 1995; Stroud et al., 2000). Women report more feelings of rejection than men across control, mild, and severe rejection conditions (Romero-Canyas et al., 2010), and subsequently more quickly return to baseline levels of distress (e.g., Matthews, Ponitz, & Morrison, 2009; Weinberg & Tronick, 1999). This divergence in emotional reactivity may emerge in adolescence and appears to be consistent across several types of stressors and measures of distress (Ordaz & Luna, 2012; Romero-Canyas et al., 2010).

The present study

The present study sought to examine sex differences in reactivity and recovery from social exclusion using both endocrine and subjective measures. While immediate reactivity to social exclusion was studied extensively (DeWall & Richman, 2011; Williams & Jarvis, 2006), data on recovery patterns have been slower to accumulate (however, see Laurent et al., 2013; Oaten et al., 2008). Empirical data on recovery patterns are crucial, as it is during this phase that individual differences in reactions to social exclusion are expected to occur (Ford & Collins, 2010; Sebastian, Viding, Williams, & Blakemore, 2010). Indeed, individual differences were found to affect regulation following social stress (Matthews et al., 2009; Weinberg & Tronick, 1999). Importantly, different endocrine indices have different temporal signatures (e.g., cortisol reactivity and ensuing recovery span longer than for sAA; Granger, Kivlighan, el-Sheikh, Gordis, & Stroud, 2007), thus measurement over relevant time periods for different markers is essential to obtain an accurate portrayal of reaction to stress. The present study assesses initial reactivity as well as temporal unfolding of subjective as well as endocrine measures.

Another goal of the present study was to examine both sAA and cortisol reactivity and recovery following one of the most commonly used paradigms for social exclusion – the Cyberball task. In this task, participants engage in the online ball tossing game with two additional virtual players (see Williams & Jarvis, 2006). In fact, ball tosses for other players are pre-determined by the experimenter, such that in the exclusion condition, participants are excluded from the game after a few initial throws. Two markers of stress – sAA and cortisol – have been examined in tandem with regards to sex differences in manipulation of physical stress (van Stegeren et al., 2008), social-evaluative stress such as public speaking (Balodis, Wynne-Edwards, & Olmstead, 2010), and competition (Kivlighan & Granger, 2006). However, no study to date has examined both those markers in response to social exclusion. Such an examination is important to understand the variations in response to this common stressor.

We expected subjective as well as endocrine measures to exhibit an initial increase followed by a decrease, with sAA showing a return to baseline within 15 minutes and cortisol recovery beginning 40 minutes following peak (Granger et al., 2007). We also expected men to exhibit a stronger cortisol reactivity than women (Kudielka et al., 1998), with no such differences in sAA and mood. Finally, we expected self-reported mood to be less negative for men (e.g., Grossman, Wilhelm, Kawachi, & Sparrow, 2001; Kirschbaum et al., 1995), and to return to baseline more swiftly for women than for men (e.g., Matthews et al., 2009; Weinberg & Tronick, 1999).

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 44 student volunteers (21 females), recruited via advertisements on campus, in exchange for either course credit or monetary compensation equivalent to $25. The participants ranged in age from 19 to 30 (M = 23.13, SD = 2.52 years). Participants using any steroid or psychiatric medication were excluded.

Participants were first screened by phone for use of medication, and then instructed to arrive at the laboratory after having consumed only water for 90 minutes prior to the beginning of the study, limiting contamination of saliva sampling. Meetings were scheduled between noon and 5 pm, in order to control for diurnal variations in hormones. Three participants did not provide enough saliva to yield reliable results, thus 20 women and 21 men were included in the final analysis.

Procedure

The study was approved by an Institutional Ethics (Helsinki) Committee. Participants were told they would participate in a study examining visualization in social interaction. Following a brief introduction to the study by the experimenter, participants signed informed consent forms, and the first mood rating was taken (T1). Next, participants were introduced to the Cyberball game, with two additional “virtual players” symbolized onscreen by standard icons (see Williams & Jarvis, 2006). As already mentioned, ball tosses for other players were pre-determined by the experimenter, such that in the exclusion condition, participants are never passed the ball following the two initial throws. Immediately following the game, which takes about five minutes, a saliva sample was taken (T2), along with mood ratings. Additional samples and mood ratings were taken every 15 minutes thereafter. This process provided a total of five time points over 75 minutes (T3–T5). At the end of the study, participants were thanked and debriefed.

Saliva sampling

Cortisol is released into the bloodstream, metabolizing and reaching saliva within 10–20 minutes, and sAA is released by the salivary gland, peaking 5–10 minutes following stress (Granger et al., 2007). Thus, for both, T2 was used as a reflection of baseline (arrival) endocrine levels. As cortisol requires a recovery phase (return to baseline) of approximately 90 minutes (Granger et al., 2007), four saliva samples were analyzed (T2-T5). sAA is found to return to baseline levels within 10–15 minutes (Granger et al., 2007), thus only three samples were analyzed (T2–T4).

Saliva samples used to measure cortisol and sAA levels were collected using Salivette sampling devices (Sarstedt, Rommelsdorf, Germany). Samples were stored at −20°C until biochemical analysis. On day of assay, all samples thawed completely, vortexed, and centrifuged at 4°C at 1500 × g for 15 minutes. All samples were visually untainted. Saliva samples were assayed in duplicate and measured according to the instructions of the kits. All samples from a particular participant were assayed on the same assay plate. Free cortisol levels were measured using a commercially available well-established High Sensitivity Salivary Cortisol Enzyme Immunoassay Kit purchased from Salimetrics (State College, Pennsylvania). All samples were within an acceptable pH range, as demonstrated by an absence of color change when indicator (as part of the assay diluents) was added. Kit sensitivity for salivary cortisol is 0.003 μg/dL. The mean intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) for this study were 2.24% and 15.61%, respectively. The sAA was measured by a quantitative enzyme kinetic method, using a commercially available kits purchased from Immuno-Biological Laboratories (Hamburg, Germany). According to the kit instructions, all samples were pre-diluted up to 1:301. The sAA metabolized specifically the 2-Chloro-4-Nitrophenyl-α-Maltotrioside (CNPG3) substrate. The intensity of the color developed was proportional to the activity of alpha amylase in the sample. The results of samples were determined directly by using the standard curve. Intra-and inter-assay CVs were 10.99% and 16.60%, respectively.

Mood rating

At each time point, participants rated their positive and negative mood on 0 (neutral) to 9 (very positive/ negative) Likert scales. The negative score was subtracted from the positive to create a composite mood score for each time point.

Results

Repeated measure ANOVAs were conducted separately for mood, cortisol, and sAA. Sex, dummy coded (0 for male, 1 for female), served as a between-subjects variable, and time as a within-subject variable. As cortisol and sAA were positively skewed, log-transformed scores were used. Sphericity was not rejected, and therefore assumed in all analyses. Quadratic effects for time were expected to represent reactivity and recovery, time by sex effects were expected to represent sex differences in reactivity and recovery, and main effects for sex were expected to represent differences between men and women in overall levels of mood, cortisol, and sAA.

Mood

For composite mood, a 2 (Sex: male, female) × 5 (Time: T1–T5) ANOVA was conducted. A significant Time effect was found (F[4,36] = 4.39, p = .002, partial η2 = 0.36), with a significant quadratic component (F[1,39] = 12.54, p = .001, partial η2 = 0.24), indicating a rise and then drop in negative mood intensity (see Figure 1). A main effect for sex (F[1,39] = 7.08, p = .01, partial η2 = 0.15) was found, with women reporting overall worse mood (M = 0.33, SD = 0.71 and M = 2.96, SD = 0.69 for women and men, respectively). The Time × Sex interaction was not significant (F[4,36] = 1.80, p = .15, partial η2 = 0.16); therefore, no sex differences were evident in mood reactivity or recovery.

Figure 1.

Changes in mood over time by sex.

Note: T1 = time 1, T2 = time 2, T3 = time 3, T4 = time 4, T5 = time 5.

Cortisol

For cortisol, a 2 (Sex) × 4 (Time: T2–T5) ANOVA was conducted. A significant effect for Time was found (F[3,37] = 6.57, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.35). While the quadratic component was not significant (F[1,39] = 0.11, p = .75, partial η2 = 0.00), both linear (F[1,39] = 14.59, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.27) and cubic (F[1,39] = 4.80, p = .04, partial η2 = 0.11) components were identified. These effects were moderated by Sex (F[3,37] = 3.20, p = .03, partial η2 = 0.21). In addition, a main effect for Sex was also found (F[1,39] = 6.53, p = .02, partial η2 = 0.14) such that women had higher cortisol levels than did men (M=1342.66, SD = 123.84 and M = 900.56, SD = 120.86, accordingly). When results are examined separately for men and women, both linear and cubic effects remained significant for men (F[1,20] = 8.98, p = .01, partial η2 = 0.31 and F[1,20] = 6.86, p = .02, partial η2 = 0.26, respectively), while only a linear effect remained for women (F[1,19] = 6.09, p = .02, partial η2 = 0.24). Males showed a non-significant rise, then significant drop, then slight rise, in cortisol over time, while women showed a gradual decline in cortisol levels throughout the experiment (see Figure 2). Post hoc pairwise comparisons, among men showed T2 to significantly differ from T4 and T5 (Mi−j = 0.25, p = .01, Mi−j = 0.23, p = .04, respectively), but not T3 (Mi−j = −2.00, p = .97), suggesting non-significant rise followed by significant decline in cortisol.

Figure 2.

Changes in cortisol over time by sex.

Note: T2 = time 2, T3 = time 3, T4 = time 4, T5 = time 5.

Salivary alpha amylase

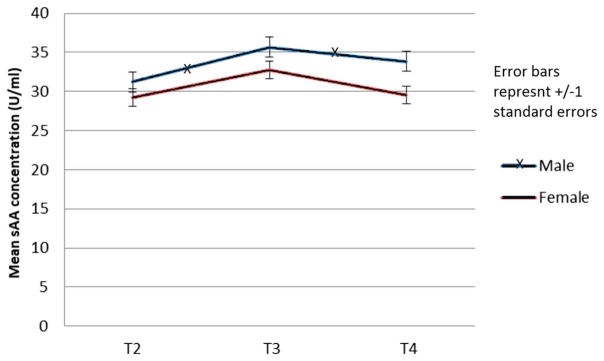

For sAA, a 2 (Sex) × 3 Time (Time: T2-T4) ANOVA was conducted. An almost-significant effect of Time was found (F[2,38] = 2.97, p = .06, partial η2 = 0.14), with a significant quadratic component (F[1,39] = 4.13, p = .049, partial η2 = 0.10) (see Figure 3). The effects of Sex and Sex by Time interactions were non-significant (F[1,39] = 0.13, p = .72 partial η2 = 0.00), and (F[2,38] = 0.05, p = .95, partial η2 = 0.00), respectively). Thus, the only significant finding was the quadratic component of the time response, indicating an overall (reactivity and recovery) response to the exclusion experience, with no effects for sex. Post hoc comparisons of T2 to T3 for sAA show significant rise (p < .001), and a significant subsequent decline from T3 to T4 (p = .04).

Figure 3.

Changes in sAA over time by sex.

Note: T2 = time 2, T3 = time 3, T4 = time 4, sAA = salivary alpha amylase.

Additional analyses examined overall reactivity in each of our dependent measures. Following our task, mood showed an average 33% decrease, and sAA showed an average 20% increase. In contrast, participants showed only a 3% mean increase in cortisol, with only three individuals (all men) meeting the 1.5 nmol/L increase criterion for response (Miller, Plessow, Kirschbaum, & Stalder, 2013).

Discussion

The literature on stress reactivity has shown great diversity in individual response of different systems, and particularly sex differences. We have found that a brief computer game with veritable strangers can affect both our subjective experience and our biology. Consistent with our hypotheses, reactivity and recovery patterns were found for SAM activity (as indicated by the rise and for of sAA), as well as for mood for the entire sample. Consistent with our sex differences hypothesis, sex differences in HPA patterns (as measured by cortisol) were found. However, our hypotheses regarding cortisol reactivity and recovery patterns in men, but not women, were not fully supported: while women showed gradual decline in cortisol over time, men showed no significant changes following Cyberball, followed by a rapid decline, and subsequent stabilization. This may indicate a delayed decay in cortisol among men, or possibly that measurement timing failed to capture a proper baseline, thus missing a response, if there was one.

The findings of no cortisol response among women are not surprising, as the process of cortisol modulation among women may be tied to estrogen, which has an attenuating effect on stress responsivity (Kajantie & Phillips, 2006). Ties between estrogen and stress responses have been supported by findings regarding the blunted stress response in oral contraceptive users (Rohleder, Wolf, Piel, & Kirschbaum, 2003), and differences in stress reactivity through the menstrual cycle: women in the luteal phase (low estrogen) have shown more reactivity than during other phases (Sita & Miller, 1996) and a profile more similar to men (Kajantie & Phillips, 2006). Studies of pre-pubertal men and women have failed to find sex differences in cortisol reactivity (Spinrad et al., 2009), and higher cortisol reactivity was found in post-menopausal women when compared to pre-menopausal women (Lindheim et al., 1992). Lack of cortisol response among men stood contrary to our hypotheses, but is in line with some previous findings with the Cyberball task (Zwolinski, 2012), and may speak to the reliability of this task in eliciting cortisol response, or to the measurement issues already discussed. Despite the absence of clear HPA involvement in reaction to social exclusion, both men and women demonstrated distress in SAM and mood measures. Lack of congruence between cortisol and mood among women has been found before, as raising cortisol was found to have a protective effect on mood responses to stress (Het & Wolf, 2007). Lack of congruence between cortisol and other measures of stress is more surprising among men, but may, again, be influenced by measurement-and task-related issues raised in the previous sections.

Regarding sex differences in mood ratings, it may be that, although both men and women experience an increase in distress following a social challenge, men are likely to report lower overall levels of distress and are less likely to describe the experience as stressful (see Kirschbaum et al., 1995).

In closing, we would like to mention several limitations of the present study. First, it has been stipulated that women have more pronounced cortisol response to some psychosocial stressors than do men (Maestripieri et al., 2010). Therefore, high cortisol values among women may reflect anticipatory anxiety regarding the experimental situation. Thus, cortisol changes due to the exclusion experience may have been masked by the lingering decay of this anticipatory anxiety, creating a downward slope profile, rather than the expected rise and fall. A baseline measure, taken at a different time, under neutral and uniform circumstances, may assist in testing this hypothesis. Second, given the relatively small sample used for this study, the effect of hormonal status in women was left unexplored. Future studies with larger sample size would be needed to examine the effects of the menstrual cycle, as well as other differences in hormonal status of women (e.g., pre-pubertal, post-menopausal, oral contraceptive users). Third, our results may have been affected by the specific exclusion task used (Cyberball), which is mild compared to other tasks evincing pronounced cortisol response such as an in-person rejection paradigm (Stroud et al., 2000). This task also was designed to specifically threat belonging (Williams & Nida, 2011), while other psychosocial stress test include also social-evaluative threat component, as in the Trier Stress Test (Brown, Weinstein, & Creswell, 2012) and Yale interpersonal stress test (Stroud et al., 2000; Dickerson, 2008). A different paradigm (e.g., chat room rejection, face-to-face exclusion) may uncover a different pattern of reactivity and recovery in both men and women as it engages additional systems. Fourth, our measurement design embodies two caveats: while a reliable and convenient proxy measure of autonomic activation (Nater et al., 2006; Nater & Rohleder, 2009), the precision of sAA in gauging this type of activation has been critiqued (e.g., Bosch et al., 2011), and our time point selection for each analysis assumed typical patterns of reactivity and recovery for each measure (see methods), and we could not test this assumption, as that would require all measures to be taken at all time points. Finally, future studies would benefit from attending to individual differences other than sex, including motivation (e.g., affiliation, achievement, power, etc.), interpersonal styles (Romero-Canyas et al., 2010), and psychopathology (e.g., social anxiety; McTeague et al., 2009) on reactivity to, and recovery from, social exclusion.

Despite these limitations, our study has confirmed the power of seemingly innocuous exclusion as a stressful experience affecting subjective feelings and biology. In bringing several endocrine and self-report measures together, it has provided a preliminary look into the complexity of sex differences in endocrine and affective response to, and recovery from, exclusion. Specifically, the results of the study lend only partial support to the sex-dependence of cortisol response and the sex neutrality of sAA. The inclusion of multiple stress measures may enable a more fine-tuned examination of adaptive as well as non-adaptive response patterns to socially stressful events. Our findings underscore the importance of understanding both the commonalities and differences of human response to threats to social belongingness.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The study was conducted with the assistance of the Israeli Science Foundation, Grant 455-10, awarded to Prof. Eva Gilboa-Schechtman, and is based on data collected in the Gilboa-Schechtman Lab as part of Liat Helpman’s doctoral work. Dr. Helpman is currently supported by National Institute of Mental Helath (NIMH) grant T32-MH096724.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank Liron Fridman, Jenny Kananov, Pavel Nikitin, and Marina Lekar for their assistance throughout the study.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Balodis IM, Wynne-Edwards KE, Olmstead MC. The other side of the curve: Examining the relationship between pre-stressor physiological responses and stress reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(9):1363–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7777651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benenson JF, Antonellis TJ, Cotton BJ, Noddin KE, Campbell KA. Sex differences in children’s formation of exclusionary alliances under scarce resource conditions. Animal Behaviour. 2008;76(2):497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.01.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benenson JF, Hodgson L, Heath S, Welch PJ. Human sexual differences in the use of social ostracism as a competitive tactic. International Journal of Primatology. 2008;29(4):1019–1035. doi: 10.1007/s10764-008-9283-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch JA, Veerman ECI, de Geus EJ, Proctor GB. α-Amylase as a reliable and convenient measure of sympathetic activity: Don’t start salivating just yet! Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(4):449–453. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Weinstein N, Creswell J. Trait mindfulness modulates neuroendocrine and affective responses to social evaluative threat. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:2037–2041. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterton RT, Vogelsong K, Lu Y. Salivary α-amylase as a measure of endogenous adrenergic activity. Clinical Physiology. 1996;16(4):433–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.1996.tb00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley MJ, Wu J, Molfese PJ, Mayes LC. Social exclusion in middle childhood: Rejection events, slow-wave neural activity, and ostracism distress. Social Neuroscience. 2010;5(5–6):483–495. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2010.500169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Richman SB. Social exclusion and the desire to reconnect. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(11):919–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00383.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson S. Emotional and physiological responses to social-evaluative threat. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2(3):1362–1378. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(3):355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MB, Collins NL. Self-esteem moderates neuroendocrine and psychological responses to interpersonal rejection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(3):405–419. doi: 10.1037/a0017345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn LM, Christenfeld N, Gerin W. Gender, social support, and cardiovascular responses to stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61(2):234–242. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00016. Retrieved from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2805640&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goenjian AK, Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Endres D, Abraham K, Geffner ME, Fairbanks LA. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity among Armenian adolescents with PTSD symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16(4):319–323. doi: 10.1023/A:1024453632458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DA, Kivlighan KT, el-Sheikh M, Gordis EB, Stroud LR. Salivary alpha-amylase in biobehavioral research: Recent developments and applications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1098:122–144. doi: 10.1196/annals.1384.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Wilhelm FH, Kawachi I, Sparrow D. Gender differences in psychophysiological responses to speech stress among older social phobics: Congruence and incongruence between self-evaluative and cardiovascular reactions. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63(5):765–777. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200109000-00010. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11573025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Het S, Wolf OT. Mood changes in response to psychosocial stress in healthy young women: Effects of pre-treatment with cortisol. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2007;121(1):11–20. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajantie E, Phillips DIW. The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(2):151–178. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Klauer T, Filipp SH, Hellhammer DH. Sex-specific effects of social support on cortisol and subjective responses to acute psychological stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1995;57(1):23–31. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199501000-00004. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7732155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlighan K, Granger DA. Salivary-amylase response to competition: Relation to gender, previous experience, and attitudes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH, Wolf OT, Pirke KM, Varadi E, … Pilz J. Differences in endocrine and psychological responses to psychosocial stress in healthy elderly subjects and the impact of a 2-week dehy-droepiandrosterone treatment. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1998;83(5):1756. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4758. Retrieved from http://jcem.endojournals.org/content/83/5/1756.short. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Kirschbaum C. Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: A review. Biological Psychology. 2005;69(1):113–132. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent HK, Powers SI, Laws H, Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Bent E, Balaban S. HPA regulation and dating couples’ behaviors during conflict: Gender-specific associations and cross-partner interactions. Physiology & Behavior. 2013;118:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindheim SR, Legro RS, Bernstein L, Stanczyk FZ, Vijod MA, Presser SC, Lobo RA. Behavioral stress responses in premenopausal and postmenopausal women and the effects of estrogen. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;167(6):1831–1836. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91783-7. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1471706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley SE, Carlson EB, Benoit M. Basal and dexamethasone suppressed salivary cortisol concentrations in a community sample of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55(9):940–945. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D, Baran NM, Sapienza P, Zingales L. Between- and within-sex variation in hormonal responses to psychological stress in a large sample of college students. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2010;13(5):413–424. doi: 10.3109/10253891003681137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews J, Ponitz C, Morrison F. Early gender differences in self-regulation and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2009;101(3):689–704. doi: 10.1037/a0014240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McTeague LM, Lang PJ, Laplante MC, Cuthbert BN, Strauss CC, Bradley MM. Fearful imagery in social phobia: Generalization, comorbidity, and physiological reactivity. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65(5):374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R, Plessow F, Kirschbaum C, Stalder T. Classification criteria for distinguishing cortisol responders from nonresponders to psychosocial stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2013;75(9):832–840. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nater UM, La Marca R, Florin L, Moses A, Langhans W, Koller MM, Ehlert U. Stress-induced changes in human salivary alpha-amylase activity – associations with adrenergic activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(1):49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nater U, Rohleder N. Salivary alpha-amylase as a non-invasive biomarker for the sympathetic nervous system: Current state of research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:486–496. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oaten M, Williams KD, Jones A, Zadro L. The effects of ostracism on self-regulation in the socially anxious. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2008;27(5):471–504. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2008.27.5.471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ordaz S, Luna B. Sex differences in physiological reactivity to acute psychosocial stress in adolescence. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(8):1135–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Peer JM, Roelofs K, Rotteveel M, van Dijk JG, Spinhoven P, Ridderinkhof KR. The effects of cortisol administration on approach-avoidance behavior: An event-related potential study. Biological Psychology. 2007;76(3):135– 146. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CR, Altemus M, Heo M, Jiang H. Salivary cortisol and psychopathology in children bereaved by the September 11, 2001 terror attacks. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):957–965. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohleder N, Chen E, Wolf JM, Miller GE. The psychobiology of trait shame in young women: Extending the social self preservation theory. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2008;27(5):523–532. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohleder N, Wolf JM, Piel M, Kirschbaum C. Impact of oral contraceptive use on glucocorticoid sensitivity of pro-inflammatory cytokine production after psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(3):261–273. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Canyas R, Downey G, Reddy KS, Rodriguez S, Cavanaugh TJ, Pelayo R. Paying to belong: When does rejection trigger ingratiation? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99(5):802–823. doi: 10.1037/a0020013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. Why zebras don’t get ulcers. 3. New York, NY: Holt Paperbacks; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. The influence of social hierarchy on primate health. Science (New York, NY) 2005;308(5722):648–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1106477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian C, Viding E, Williams KD, Blakemore SJ. Social brain development and the affective consequences of ostracism in adolescence. Brain and Cognition. 2010;72(1):134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel EM, Silani G, Metzler H, Thaler H, Lamm C, Gur RC, … Derntl B. The impact of social exclusion vs. inclusion on subjective and hormonal reactions in females and males. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(12):2925–2932. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sita A, Miller SB. Estradiol, progesterone and cardiovascular response to stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21(3):339–346. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Granger DA, Eggum ND, Sallquist J, Haugen RG, … Hofer C. Individual differences in preschoolers’ salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase reactivity: Relations to temperament and maladjustment. Hormones and Behavior. 2009;56(1):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stegeren AH, Wolf OT, Kindt M. Salivary alpha amylase and cortisol responses to different stress tasks: Impact of sex. International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology. 2008;69(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratakis C, Chrousos G. Neuroendocrinology and pathophysiology of the stress system. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1995;771:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44666.x. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44666.x/full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LR, Foster E, Papandonatos GD, Handwerger K, Granger DA, Kivlighan KT, Niaura R. Stress response and the adolescent transition: Performance versus peer rejection stressors. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(1):47–68. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LR, Salovey P, Epel ES. Sex differences in stress responses: Social rejection versus achievement stress. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(4):318–327. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Salovey P. The Yale interpersonal stressor (YIPS): Affective, physiological, and behavioral responses to a novel interpersonal rejection paradigm. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;22(3):204–213. doi: 10.1007/BF02895115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RAR, Updegraff JA. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review. 2000;107(3):411–429. doi: 10.1037//0033-295X.107.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53(4):865–871. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhart M, Chong RY, Oswald L, Lin PI, Wand GS. Gender differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(5):642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veen JF, van Vliet IM, Derijk RH, van Pelt J, Mertens B, Zitman FG. Elevated alpha-amylase but not cortisol in generalized social anxiety disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(10):1313–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil JM, Geary DC, Granger DA, Flinn MV. Sex differences in salivary cortisol, alpha-amylase, and psychological functioning following Hurricane Katrina. Child Development. 2010;81(4):1228–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weik U, Maroof P, Zöller C, Deinzer R. Pre-experience of social exclusion suppresses cortisol response to psychosocial stress in women but not in men. Hormones and Behavior. 2010;58(5):891–897. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg M, Tronick E. Gender differences in emotional expressivity and self-regulation during early infancy. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(1):175–188. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.175. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/dev/35/1/175/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Jarvis B. Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior Research Methods. 2006;38(1):174–180. doi: 10.3758/BF03192765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Nida S. Ostracism: Consequences and coping. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20(2):71–75. doi: 10.1177/0963721411402480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth MM, Welsh KM, Schultheiss OC. Salivary cortisol changes in humans after winning or losing a dominance contest depend on implicit power motivation. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;49(3):346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadro L, Williams KD, Richardson R. How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2004;40(4):560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2003.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zakowski JJ, Bruns DE. Biochemistry of human alpha amylase isoenzymes. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 1985;21(4):283–322. doi: 10.3109/10408368509165786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zöller C, Maroof P, Weik U, Deinzer R. No effect of social exclusion on salivary cortisol secretion in women in a randomized controlled study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(9):1294–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwolinski J. Psychological and neuroendocrine reactivity to ostracism. Aggressive Behavior. 2012;38:108–125. doi: 10.1002/ab.21411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]