Abstract

Background

Achieving a satisfying quality of life for a patient by applying individually matched therapy is, simultaneously, a great challenge and a priority for contemporary medicine. Patients with visible dermatological ailments are particularly susceptible to reduction in the general quality of life. Among the dermatological diseases, acne causes considerable reduction in the quality of life and changes in self-perception that lead to the worsening of a patient’s mental condition, including depression and suicidal thoughts. As a result, difficulties in contact with loved ones, as well as social and professional problems are observed, which show that acne is not a somatic problem alone. To a large extent, it becomes a part of psychodermatology, becoming an important topic of public health in social medicine practice. Pharmacological treatment of acne is a challenge for a dermatologist and often requires the necessity of cooperating with a cosmetologist. Cosmetological treatments are aimed at improving the condition of the skin and reduction or subsiding of acne skin changes.

Aim

The aim of this study was to assess the influence of selected cosmetological treatments on the general quality of life of patients with acne.

Materials and methods

The study group consisted of 101 women aged 19–29 years ( years, SD =2.3 years). All subjects were diagnosed with acne vulgaris of the face. In the study group, the acne changes occurred over the course of 3–15 years ( years, SD =2.7 years). Selected cosmetological treatments (intensive pulsing light, alpha-hydroxy acids, cavitation peeling, needle-free mesotherapy, diamond microdermabrasion and sonophoresis) were performed in series in the number depending on the particular patient’s chosen treatment, after excluding contraindications. General quality of life of the patients was estimated using the Skindex-29 and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaires, before and after the cosmetological treatment.

Results

Statistical analysis of the data obtained from the Skindex-29 questionnaire in areas (emotions, symptoms and physical functioning) and DLQI questionnaire in areas (daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relations and treatment) showed great improvement in the general quality of life after applying a series of cosmetological treatments. The results are statistically relevant at P<0.0001.

Conclusion

The cosmetological treatment significantly improved the general quality of life of patients with acne vulgaris and their skin condition, which was evaluated by the Hellgren–Vincent scale. It was proven that therapy performed in cosmetological clinics may become an integral part of or complete dermatological treatment.

Keywords: acne vulgaris, quality of life, cosmetological treatments

Introduction

The term “quality of life” (QoL) is used in numerous academic disciplines, such as philosophy and sociology and recently medicine as well. For each person, the term may mean something different; however, crucially, QoL affects the daily activity of each of us.1

Earlier, the definition of QoL was associated with the standard of living defined mainly by material goods, but the modern definition of the QoL, established after World War II in the United States, and generally accepted in the world, explains that money does not ensure the fulfillment of human needs in all aspects; thus, the definition was expanded to include intangible values concerning family, work and social life.2,3

QoL is a vital term in medicine, which is very important from a psychological point of view. It defines all aspects of patients’ well-being with reference to a disease with which they struggle.4

In the 21st century, there are many changes in terms of the main criteria of people’s perception, where appearance, thereby the condition of their skin, has become an important indicator of QoL. Since skin is the largest organ, serving many functions, it is exposed directly to environmental factors leading to dermatological diseases, with various morphological changes in the skin resulting in considerable reduction in the general QoL.5 Among dermatological diseases, acne vulgaris is an ailment that may lead to trauma, as well as depression, suicidal thoughts or even suicide attempts. The prevalence of mental disorders in patients with skin diseases is estimated to be 30%–60%.6 Acne vulgaris causes considerable reduction in QoL and distorted self-perception connected with skin changes, post-acne scars or hyperpigmentation.7 Factors that contribute to the occurrence of the disease are as follows: colonization of Propionibacterium acnes in sebaceous glands, overproduction of sebum, development of inflammation, excessive keratinization of the epidermis in follicle opening and genetic factors.8 Factors that exacerbate the course of the disease include hormonal disorders, inappropriate diet, too long exposure of the skin to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, smoking and drugs (anabolic steroids, glucocorticoids, antidepressants and vitamin B12).9–11

Moreover, it is difficult to predict the duration of acne vulgaris. Therapy is often an arduous process requiring long treatment periods lasting from several months to several years.12 Post-acne changes may result in growing frustration of patients as well as in the sense of the lack of attractiveness, especially in the impression of being rejected by society, particularly in teenagers who strongly associate attractiveness with appearance. Patients often feel unaccepted which leads to social and professional withdrawal. Therefore, the immediate help of dermatologist, psychologist and cosmetologist is important.13

Contemporary medicine has a possibility of monitoring the general QoL of patients by means of special questionnaires that can be divided into general (ie, allergical and dermatological) and specific to a particular disease (ie, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis and acne vulgaris), and filling validated questionnaires before and after treatment allows comparing how it influenced a patient’s general QoL.14,15 Questionnaires such as Skindex-29 and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) are used in estimating the QoL of patients with acne vulgaris.16,17

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to assess the influence of selected cosmetological treatments on the general QoL of patients with acne vulgaris using the Skindex-29 and DLQI questionnaires.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Wroclaw Medical University (No. KB – 462/2013), and all patients involved in the study have provided written informed consent.

The study group consisted of 101 women aged 19–29 years ( years, SD =2.3 years). All subjects were diagnosed with acne vulgaris in the face. In the study group, acne changes occurred in the course of 3–15 years ( years, SD =2.7 years). Based on dermatological examination, patients’ skin condition and severity of skin lesions were determined according to the 5-step Hellgren–Vincent scale, in which the pretreatment results ranged from 1.0 to 3.0 points ( points, SD =0.6 points).

The most common type of the acne was acne punctata (42%), then acne papulous (36%), acne pustular (14%) and acne papulopustular (9%). The study participants were divided into three groups depending on the type of cosmetological treatment applied: 1) sonophoresis; 2) non-needle mesotherapy and 3) intensive pulsing light (IPL), cavitation peeling, alpha-hydroxy acids (AHAs) and diamond microdermabrasion. Before and after treatment, each patient filled out the validated questionnaires, Skindex-29 and DLQI. For statistical analysis, programs such as Statistica 10 and Microsoft Excel 2007 were used. For quantitative variables, the arithmetic mean, as well as SD and range of variation (extreme values), was calculated. For qualitative variables, the frequency of occurrence was calculated (percent). All studied variables of quantitative type were verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test for determining the kind of layout. To compare the results, Student’s t-test was applied. More than two groups were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc tests. For all comparisons, the level α =0.05 was accepted and the obtained P-values were rounded off to four decimal points. In addition, dependency between the chosen variables was determined using Pearson’s correlation test (α =0.05).

Results

Severity of skin lesions measured by Hellgren–Vincent scale revealed that the pretreatment results ranged from 1.0 to 3.0 points ( points, SD =0.6 points) and posttreatment ranged from 1.0 to 2.0 points ( points, SD =0.4 points). Comparison of pre and posttreatment results showed statistically significant differences (P<0.0001) in improving the skin condition.

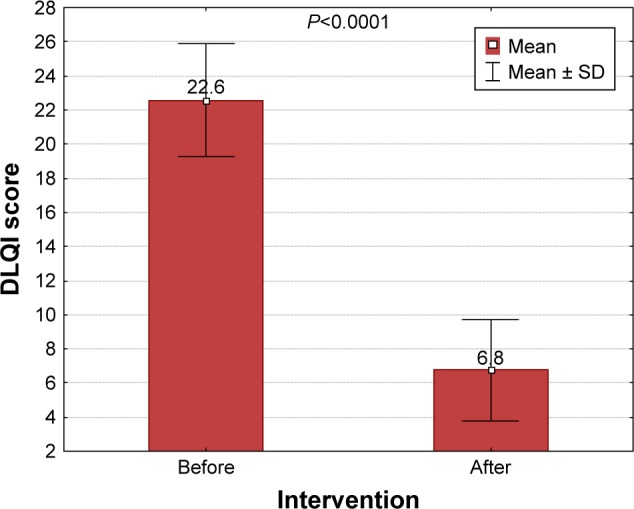

General analysis of the results of DLQI questionnaire showed that before therapy, the assessment of the QoL ranged from 11 to 30 points ( points, SD =3.3 points), and after cosmetological treatment, it was 0–16 points ( points, SD =3.0 points), which indicated statistically significant improvement in the QoL of tested patients (P<0.0001; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of scoring results of DLQI questionnaire before and after cosmetological treatment.

Abbreviation: DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index.

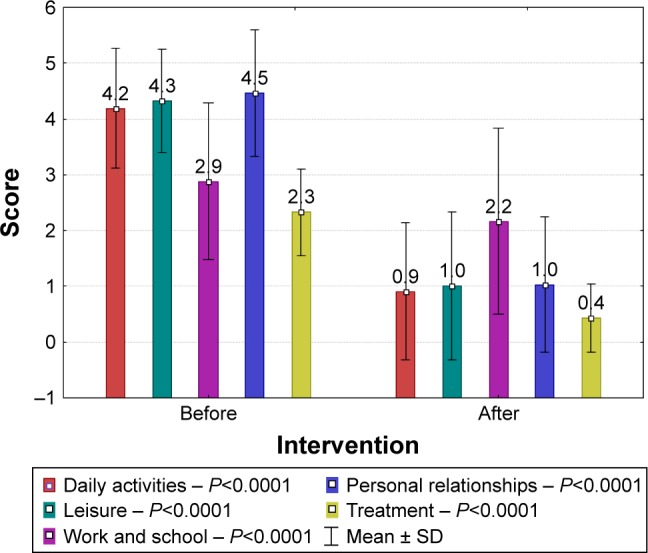

Juxtaposition of particular parts of the DLQI questionnaire (daily activities, leisure, school and work, personal relations and treatment) before and after cosmetological treatment revealed statistically significant decrease in the number of points in each of the abovementioned parts of the questionnaire. The number of points assessing daily activities decreased from the average level of 4.2 points (minimum–maximum: 1–6 points, SD =1.1 points) to 0.9 points (minimum–maximum: 0–5 points, SD =1.2 points; P<0.0001), leisure from 4.3 points (minimum–maximum: 1–6 points, SD =0.9 points) to 1.0 (minimum–maximum: 0–6 points, SD =1.3 points; P<0.0001), work and school from 2.9 points (minimum–maximum: 0–6 points, SD =1.4 points) to 2.2 points (minimum–maximum: 1–5 points, SD =1.7 points; P<0.0001), personal relations from 4.5 points (minimum–maximum: 1–6 points, SD =1.1 points) to 1.0 point (minimum–maximum: 0–6 points, SD =1.2 points; P<0.0001) and treatment from 2.3 points (minimum–maximum: 0–3 points, SD =0.8 points) to 0.4 points (minimum–maximum: 0–3 points, SD =0.6 points; P<0.0001). These data attest the improvement in the QoL in all aspects included in the abovementioned parts of the DLQI questionnaire (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of scoring results of the particular parts of DLQI questionnaire before and after cosmetological treatment.

Abbreviation: DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index.

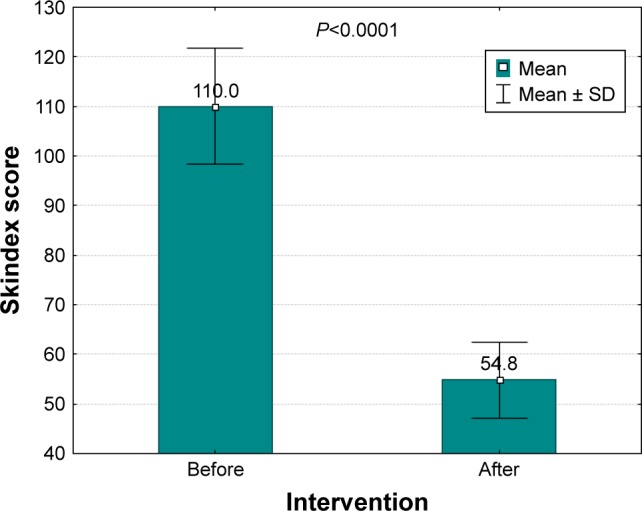

The comparison of the general results of the Skindex-29 questionnaire revealed that there appeared a remarkable reduction in the number of points after cosmetological treatment. The scoring assessment before treatment ranged from 62.0 to 142.0 points ( points, SD =7.7 points). The discrepancies of the results were statistically significant (P<0.0001) which proved a remarkable improvement in the QoL of the study participants (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of scoring results of Skindex-29 questionnaire before and after cosmetological treatment.

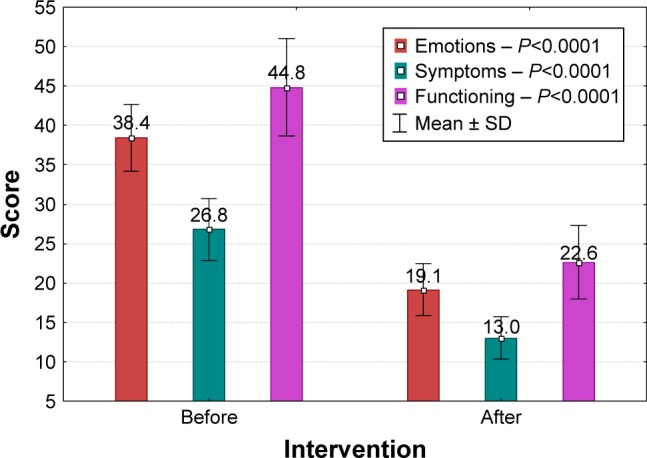

Scoring assessment of the components of the Skindex-29 questionnaire (emotions, symptoms, functioning) indicated statistically significant reduction in the number of points scored after cosmetological treatment. The average result of the component emotions before treatment was 34.8 points (minimum–maximum: 26–49 points, SD =4.3 points) and after treatment was 19.1 points (minimum–maximum: 11–30 points, SD =3.3 points; P<0.0001). The results of the assessment in other components of the Skindex 29 questionnaire were as follows: symptoms before treatment 26.8 points (minimum–maximum: 14–34 points, SD =4.0 points) and after treatment 13 points (minimum–maximum: 8–21 points, SD =2.7 points; P<0.0001); functioning before treatment 44.8 points (minimum–maximum: 15–59 points, SD =6.2 points) and after treatment 22.6 points (minimum–maximum: 12–33 points, SD =4.6 points; P<0.0001). These results attest the improvement in the QoL in all aspects included in the particular parts of the Skindex-29 questionnaire (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of particular components of the Skindex-29 questionnaire before and after cosmetological treatment.

Discussion

Currently, the appearance and skin condition are vitally important elements and even become a priority for a majority of populations, especially in younger age groups, being an important criterion for judging other people.18 Commonly existing cult of perfect appearance makes every defect of the body, especially symptoms of skin disease negatively influence the life of patients and their families. As a result, a destabilization of family or professional life and even significant changes in the human psyche may occur.7,18 Acnevulgaris is a disease greatly influencing the QoL of the patients suffering from ailments. They often emphasize that psychological limitations and destabilization of personal and professional aspects of their lives appear.19 The problem of acne should be considered multidimensionally; therefore, a holistic approach and close cooperation of a dermatologist, psychologist and cosmetologist are crucial.20

The results of the current study clearly show that cosmetological treatment significantly influences the improvement in the QoL of the study participants in parallel to better condition of their skin. Comparable results have been obtained by Kurtalić et al21 who showed that, applying the Skindex-29 scale in their study, the QoL of patients with acne vulgaris was significantly reduced, but during cosmetological treatment those who noticed even a small improvement in the skin condition began to report first signals of the improvement in the QoL and family relations. It has been observed that even the smallest positive changes in patients’ appearance influence their personal life and relations with other people.22 As far as DLQI scale is concerned, the results of the current study resemble those of Akyazi et al23 who indicated a great importance of cosmetological treatment in the QoL improvement: the average number of points was 9 before treatment (with the maximum being 10) and 2 after treatment (P<0.0005). This study, as well as those of other authors, indicates that cosmetological treatment is an important component in improving the QoL of patients with skin problems. Thus, properly matched treatment carried on in series influences the improvement in the appearance of the skin of the study participants to a great extent.

Conclusion

The study reveals that patients undergoing therapy communicate that even the smallest improvement in the skin condition increases their QoL and provides them with the hope of returning to a normal life and improving the family relations. This is important, as skin diseases impact, to a great extent, not only personal life but also daily functioning at work and school. People are not understood by society, which excludes them from daily life, causes a reduction in QoL and generates anxiety attacks, depression, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts.24 Interestingly enough, Cheng et al5 reported 83% of adolescents never having seen a physician for their acne. Thus, multidisciplinary help and a holistic approach to a patient are important, ensuring faster recovery. Dermatological treatment, the help of a psychologist and cooperation with a cosmetologist guarantee faster recovery than applying one-directional treatment.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Higaki Y, Tanaka M, Futei Y, Kamo T, Basra MK, Finlay AY. Japanese version of the family dermatology life quality index: translation and validation. J Dermatol. 2017 Mar 24; doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13831. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finlay AY. Broader concepts of quality of life measurement, encompassing validation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Apr 1; doi: 10.1111/jdv.14254. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hrehorów E, Salomon J, Matusiak L, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Patients with psoriasis feel stigmatized. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(1):67–72. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng CE, Irwin B, Mauriello D, Liang L, Pappert A, Kimball AB. Self-reported acne severity, treatment, and belief patterns across multiple racial and ethnic groups in adolescent students. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(5):446–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta M, Gupta A. Psychiatric and psychological co-morbidity in patients with dermatologic disorders: epidemiology and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4(12):833–842. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szepietowski J, Kapińska-Mrowiecka M, Kaszuba A, et al. Acne vulgaris: pathogenesis and treatment. Consensus of the polish dermatological society. Dermatol Rev. 2012;6:649–673. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makrantonaki E, Ganceviciene R, Zouboulis C. An update on the role of the sebaceous gland in the pathogenesis of acne. Dermatoendocrinology. 2011;3(1):41–49. doi: 10.4161/derm.3.1.13900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melnik B, John S, Schmitz G. Over-stimulation of insulin/IGF-1 signaling by western diet may promote diseases of civilization: lessons learnt from Laron syndrome. Nutr Metab. 2011;8:41–43. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leyden JJ, Gollnick H, Thiboutot D, et al. The hypothetical role of FoxO1 in acne is interesting, but more study is needed before any conclusions can be drawn. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(6):1365–1366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith E, Grindlay D, Williams C. What’s new in acne? An analysis of systematic reviews published in 2009–2010. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;36(2):119–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geng A, Weinstock M, Hall R, et al. VATTC Trial Group Tolerability of high-dose topical tretinoin: the veterans affairs topical tretinoin chemoprevention trial. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(4):918–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483–489. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S99225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wojtkiewicz M, Panaszek B. Evaluative potentials of impact of urticaria and angio-oedema on patients quality of life. Postep Dermi Alergol. 2010;27:291–296. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker N, Lewis-Jones MS. Quality of life and acne in Scottish adolescent schoolchildren: use of the children’s dermatology life quality index (CDLQI) and the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(1):45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis V, Finlay AY. Ten years experience of the dermatology life quality index (DLQI) J Invest Dermatol. 2004;9(2):169–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.09113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagliarello C, Di Pietro C, Tabolli S. A comprehensive health impact assessment and determinants of quality of life, health and psychological status in acne patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2015;150(3):303–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanisah A, Omar K, Shah SA. Prevalence of acne and its impact on the quality of life in school-aged adolescents in Malaysia. J Prim Health Care. 2009;1(1):20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niemeier V, Kupfer J, Gieler U. Acne vulgaris – psychosomatic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2006;4(12):1027–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2006.06110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper AJ, Harris VR. Modern management of acne. Med J Aust. 2017;206(1):41–45. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtalić N, Hadzigrahić N, Tahirović H, Sijercić N. Quality of life of adolescents with acne vulgaris. Acta Med Croatica. 2010;64(4):247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosthota A, Bondade S, Basavaraja V. Impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and self-esteem. Cutis. 2016;98(2):121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akyazi H, Baltacı D, Alpay K, Hocaoğlu Ç. Quality of life patients with acne vulgaris before and after treatment. Dicle Med J. 2011;38(3):282–288. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purvis D, Robinson E, Merry S, Watson P. Acne, anxiety depression and suicide in teenagers: a cross-sectional survey of New Zealand secondary school students. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42(12):793–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]