ABSTRACT

The global tobacco industry, from the 1960s to mid 1990s, saw consolidation and eventual domination by a small number of transnational tobacco companies (TTC). This paper draws together comparative analysis of five case studies in the special issue on ‘The Emergence of Asian Tobacco Companies: Implications for Global Health Governance.’ The cases suggest that tobacco industry globalisation is undergoing a new phase, beginning in the late 1990s, with the adoption of global business strategies by five Asian companies. The strategies were prompted foremost by external factors, notably market liberalisation, competition from TTCs and declining domestic markets. State protection and promotion enabled the industries in Japan, South Korea and China to rationalise their operations ahead of foreign market expansion. The TTM and TTL will likely remain domestic or perhaps regional companies, JTI and KT&G have achieved TTC status, and the CNTC is poised to dwarf all existing companies. This global expansion of Asian tobacco companies will increase competition which, in turn, will intensify marketing, exert downward price pressures along the global value chain, and encourage product innovation. Global tobacco control requires fuller understanding of these emerging changes and the regulatory challenges posed by ongoing globalisation.

KEYWORDS: Tobacco industry, transnational tobacco companies, Asia, globalisation, global business strategy

Introduction

The global transformation of tobacco production and consumption since the 1960s, resulting in the industry’s structural consolidation, expansion into emerging markets, has led to a marked rise in tobacco-related disease and death worldwide (Glynn, Seffrin, Brawley, Grey, & Ross, 2010). There is widespread recognition, in turn, that collective action is needed to stem this ‘tobacco pandemic.’ In large part, effective global tobacco governance is premised on fuller understanding of the nature and dynamics of tobacco industry globalisation (Madhu, 2013). However, a recent systematic review of the public health literature on tobacco industry globalisation to date finds a lack of explicit definition and measurement, a focus on existing transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) and limited attention to developments since the 2000s (Lee, Eckhardt, & Holden, 2016).

The case studies in this special issue, using a common analytical framework (Lee & Eckhardt, 2016), contribute to an expanded understanding of tobacco industry globalisation by analysing the business strategies of five Asian tobacco companies: Japan Tobacco International (JTI) (MacKenzie, Eckhardt, & Prastyani, 2017),1 China National Tobacco Corporation (CNTC) (Fang, Sejpal, & Lee, 2016), Korean Tobacco & Ginseng (now known only as KT&G) (Lee, Gong, Eckhardt, Holden, & Lee, 2017), Taiwan Tobacco and Liquor Corporation (TTL) (Eckhardt, Fang and Lee, 2017) and Thailand Tobacco Monopoly (TTM) (MacKenzie, Ross, & Lee, 2017). Of these companies, JTI is already a leading TTC, while the others are potentially emerging TTCs. This paper brings together the main findings of the case studies by undertaking a comparative analysis along three key questions set out in the framework: (a) what are the primary factors behind the push for globalisation?; (b) what are the specific globalisation strategies pursued?; and (c) to what extent has the specific company in question, globalised to date? As well as drawing together the detailed analysis of each company provided in the case studies, this comparative analysis offer insights regarding implications for the global tobacco industry, tobacco control and future research directions.

Findings

What are the key factors behind the global business strategies of the five Asian tobacco companies?

Prior to the 1980s, the domestic tobacco markets of the five Asian countries were supplied by state-owned firms, operating as protected monopolies, and there was little commercial incentive to change. The case studies suggest that market opening, and increased competition from TTCs, were the primary drivers prompting, and then shaping, their global business strategies. This liberalisation process started in the 1980s, when Philip Morris International (PMI), RJ Reynolds (RJR) and Brown & Williamson (B&W) established the US Cigarette Export Association. Seeking to compensate for declining markets elsewhere, they lobbied the US Trade Representative (USTR) to pressure the Asian governments to increase access to their tobacco markets. The US companies successfully convinced the USTR to convey the message to its trading partners of the ‘importance of cigarette exports to U.S. trade interests’ (as quoted in MacKay, 1992). USTR pressure was then exerted (Table 1) through so-called Section 301 of the US Trade Act (1974). Section 301 is ‘the principal statutory authority under which the US may impose trade sanctions on foreign countries that either violate trade agreements or engage in other unfair trade practices’ (US Department of Commerce, n.d.). It formed part of a more aggressive unilateral approach to trade policy, to enhance bargaining power during multilateral trade negotiations at the time (Elsig & Eckhardt, 2015). Importantly, under Section 310 (known as ‘Super 301’)2 later affirmed by a subsequent World Trade Organization (WTO) decision, the US government could even act unilaterally without referring a case to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) or WTO. Table 1 provides an overview of USTR actions in the countries covered in this special issue, and the responses in terms of trade liberalisation by the Asian countries in question.

Table 1. USTR action and responses by Asian case study countries.

| Country | Year | USTR Action | Response to USTR |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 1991 | Letter from Assistant USTR to China’s National Health Education Institute on ‘discriminatory Chinese government import controls’ causing cigarette exports to be lowest in years | |

| 1994 | Threat of US$3.9 billion retaliatory tariffs against Chinese exports, under Section 301, unless US tobacco companies permitted access to domestic market | ||

| Lobbying of USTR and CNTC ahead of WTO accession | |||

| Japan | 1982 | Import tariffs reduced (90–20%) and TTCs permitted to advertise on TV, billboards and print media; shops licensed to sell imported brands increased (15k–260k) | |

| 1985 | USTR announces investigation of Japanese restrictions on cigarette imports | ||

| 1987 | Ad valorum tax on imported cigarettes removed | ||

| South Korea | 1987 | USCEA files petition with USTR to request assistance; five meetings between Korea and US to resolve dispute | |

| 1988 | USTR initiates investigation and consultation with Korean government under Section 301 officials | US and Korea sign Record of Understanding providing open and nondiscrimatory access to US tobacco companies | |

| Taiwan | 1986 | Threat of unilateral trade sanctions under Section 301 | Agreement signed with USTR to open markets |

| 1992 | USTR claim that National Tobacco Control law has ‘potential inconsistencies’ with US Trade Act (1974) and advised ‘active consideration’ of Taiwan’s GATT application | Adoption of National Tobacco Control Law | |

| Thailand | 1989 | USTR refers dispute to GATT which finds in favour of the US government | Ministry of Finance announces lifting of restrictions on foreign-made cigarettes but rescinded under pressure from civil society organisations and tobacco control advocates |

| 1990 | Thai government lifts tobacco import restrictions and adopts stronger tobacco control measures to apply to the products of both domestic and foreign companies |

A second wave of industry liberalisation began in the 1990s with the creation of the WTO in 1995. Japan, South Korea and Thailand became founding members, while China and Taiwan entered into accession negotiations. A further lowering of trade barriers on tobacco products, as well as reduced state involvement in the national companies, were key issues during these negotiations. For instance, tobacco liberalisation is mentioned 119 times in the WTO accession agreement for Taiwan, far more than any other product. Tobacco liberalisation also played an important role during China’s accessions negotiations. Holden et al. (2010) document how British American Tobacco (BAT) attempted to influence Chinese negotiations through, for example, personal access to policymakers, and use of business groups such as the European Round Table. This led to many concessions and a significant reorganisation of CNTC, such as retail distribution, but a failure to break the CNTC monopoly. Together, trade pressure and negotiations enabled TTCs to expand access to these Asian markets. In four of the countries, in turn, this motivated tobacco companies to develop their own global business strategies.

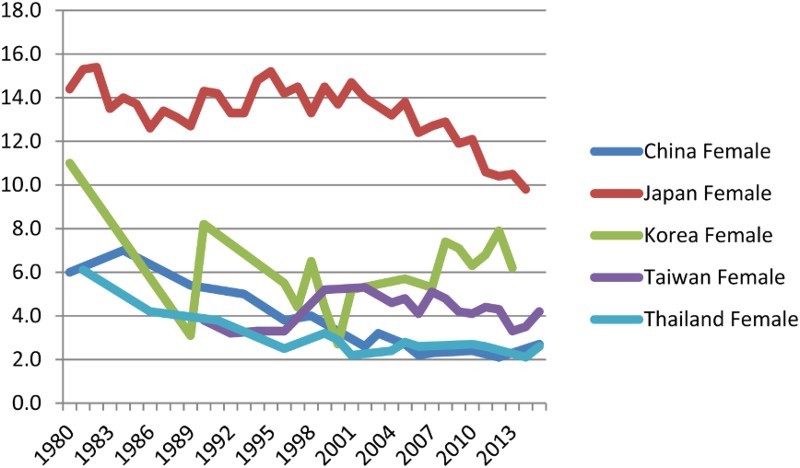

Alongside shifting market conditions, changing cultural values and norms contributed to a decline in domestic demand for tobacco products over time (Figures 1 and 2). For four companies, foreign competition eroded market share at home (Table 2), prompting feelings of nationalism and stronger tobacco control measures in Thailand and South Korea. In China, although the CNTC continued to heavily dominate, curtailed growth since 2010 has prompted fears of market saturation. This has prompted the CNTC to look increasingly outwards.

Figure 1.

Smoking prevalence among adult males in five Asian countries, 1980–2014. Source: Compiled from Health Promotion Administration, Republic of Taiwan (2016), Japan Health Promotion and Fitness Foundation (n.d.), MacKenzie, Ross, et al. (2017), Ministry of Health and Welfare (n.d.), WHO (2011), WHO (2015).

Figure 2.

Smoking prevalence among adult females in five Asian countries, 1980–2014. Source: Compiled from Health Promotion Administration, Republic of Taiwan (2016), Japan Health Promotion and Fitness Foundation (n.d.), MacKenzie, Ross, et al. (2017), Ministry of Health and Welfare (n.d.), WHO (2011), WHO (2015).

Table 2. Market share of foreign companies over time.

| Year market opened | Japan (1987) | South Korea (1989) | Taiwan (1987) | Thailand (1990) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year before market entry | 5% | 0.1% | 2% | 1% |

| 1990 | 13% | 5% | 16% | 1% |

| 1993 | 19% | 6% | 33% | 3% |

| 1995 | 18% | 14% | 27% | 5% |

| 1998 | 30% | 8% | 38% | 13% |

| 2000 | 24% | 9% | 48% | 18% |

| 2010 | 37% | 41.8% | 68.7% | 34.3% |

| 2014 | 40.3% | 37.8% | 71.8% | 30.7% |

Applying the four reasons why a firm may pursue a global business strategy (for a summary see Table 3), identified by Dunning and Lundan (2008), the five companies can be described as ‘market seekers’ when faced with steadily declining domestic markets. Additionally, JTI, and more recently CNTC and KT&G, were ‘strategic asset seekers’, using M&As, joint ventures and other forms of foreign direct investment (FDI) to extend manufacturing capacity to target markets. CNTC is also increasingly investing in contracting farmers in Asia and Africa to secure leaf supplies for domestic and export manufacturing. The restructuring of domestic operations by KT&G, CNTC and, to a far lesser extent TTM, were as ‘efficiency seekers’ given the prospect of foreign competition following market liberalisation.

Table 3. Reasons for pursuing global business strategy by five Asian tobacco companies.

| Company | Natural resource seeker | Market seeker | Efficiency seeker | Strategic asset seeker |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNTC | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| JTI | √ | √ | ||

| KT&G | √ | √ | √ | |

| TTL | √ | |||

| TTM | √ | √ |

Which global business strategies have Asian companies pursued?

As set out in the introductory paper of this special issue (Lee & Eckhardt, 2016), tobacco firms can pursue a range of business strategies when seeking to globalise. A key strategy for all five firms was exporting directly to foreign markets for which they received considerable support from their respective governments. This strategy fits with the East Asian development model which is characterised by, for instance, high investment ratios, export-oriented growth and strong government intervention in economic policy (Kuznets, 1988). For the tobacco industry, this entailed a delicate balance between assuaging foreign pressures to liberalise the domestic markets, protecting valuable state-owned enterprises, and investing to stimulate globally competitive exports.

The case studies describe how this was achieved in each country. Following market liberalisation, the five Asian companies remained state-owned enterprises, and M&As or joint ventures with TTCs were limited. Market liberalisation was more gradual than, for instance, Latin America and Eastern Europe where an import substitution model of development was pursued. The East Asian development model supported government investment in domestic consolidation, restructuring and investment in order to become more competitive domestically and abroad. The case studies find that all five companies restructured and rationalised their domestic operations ahead of foreign competition. This included closing facilities deemed inefficient, merging smaller concerns into larger ones, and upgrading production capacity. Japan, South Korea and China were successful, in this respect, at strengthening rather than weakening their domestic industries, in order to strengthen export capacity. Privatisation, in part for JTI, and in whole for KT&G, came only after the Japanese and Korean governments deemed the companies sufficiently competitive as exporters. The changes adopted by TTL and TTM have been the least extensive to date. Thailand’s political instability has led to indecision and delay, thus thwarting privatisation plans. In Taiwan, privatisation has been debated for two decades, but the government has remained fearful of job losses and a foreign takeover and, thus, hesitant until the TTL is deemed sufficiently competitive. Internal documents of BAT, for example, describe the TTC’s intention to buy TTL.

Besides exports, JTI, KT&G and CNTC have established their own overseas operations through M&As, joint ventures and FDI. Acquisitions suggest an initial strategy by JTI of horizontal (e.g. purchase of Rothmans and Gallahers) integration, to assume the status of a TTC. Consolidation of the global industry has meant M&A has been less possible, as a strategy for growth, given fewer smaller companies available for purchase. Instead, KT&G and CNTC have relied on joint ventures and FDI, as well as vertical integration, the purchase of operations across the production chain, from leaf growing to manufacturing. The smaller concerns of TTL and TTM have not established overseas operations to date given more limited capital.

Product development has also been central to the global business strategies of Asian tobacco companies. JTI and KT&G have been most successful at creating flagship brands which have achieved global appeal beyond domestic markets. JTI relies on eight brands for 60% of sales, as well as, one hundred tobacco products concentrating on three key portfolio categories: manufactured cigarettes; fine or loose cut tobacco; and what are described as ‘emerging products’ such as snus and shisha. KT&G has successfully focused on creating and promoting higher quality, western style brands, such as the flagship Esse brand family, to reposition itself as a global company, along with premium brands which earn higher profit margins. They have also been the source of product innovation including the design of filters, use of flavourings, superslim cigarettes and electronic cigarettes, in part, to respond to stronger tobacco control regulation such as standardised packaging and public smoking restrictions. While CNTC has dramatically reduced the number of Chinese brands, to achieve economies of scale, there is not yet substantial foreign demand beyond diaspora.

Lack of access to detailed and comparable data on operations and business strategy over time means it is not possible to apply the ownership, location and internalisation (OLI) framework to the five Asian companies. It is not possible, therefore, to analyse the internal characteristics of the five firms in any comparative way. From available data, however, it appears that the capacity of each to respond to external factors corresponds with the OLI approach. JTI, KT&G and CNTC illustrate ownership advantages, in particular, by using their substantial assets to strengthen their operations before establishing outward-looking strategies. KT&G and CNTC focused on improving productivity, through domestic consolidation, allowing firms with higher productivity to continue.

How globalised are Asian tobacco companies to date?

Based on the findings of the five case studies, the five companies can be located along a continuum from the mostto the least globalised. JTI, as the first Asian tobacco company to join the ranks of TTCs, demonstrates the most ‘geographical spread and … functional integration’ (Dicken, 2011, p. 7). Following its creation in 1999, JTI modelled itself after existing TTCs, such as PMI and BAT, initially pursuing diversification into non-tobacco sectors. Its success in tobacco, however, was re-established by major takeovers, including Rothmans and Gallahers, which soon provided JTI with brands, production capacity and market access on a scale to rival other TTCs. KT&G appears to be well-positioned to follow in JTI’s footsteps. Its privatisation and incorporation as a publicly traded company in 2002, product range and adoption of business practices already proven effective by existing TTCs, suggests an increasingly globalised company. This is also reflected in the nature of KT&G’s marketing campaigns, CSR initiatives and quality control systems. In both cases, mimicking TTCs was undertaken within the East Asian development model. While tobacco companies in Latin America and Eastern Europe were taken over by TTCs (Gilmore & McKee, 2004; Shepherd, 1985), state protection and promotion in Asia explains why JTI and KT&G emerged as new TTCs. Figure 3 provides comparative data on total exports.

Figure 3.

Exports by Asian company, 2000–2014. Source: Compiled from China Tobacco Yearbook, various years; KT&G annual reports, 2002–2013; Taiwan Tobacco and Liquor Corporation annual reports, 2009–2014; and Thailand Tobacco Monopoly annual reports, 2004–2013.

The Chinese company CNTC, however, is perhaps the most important to watch. The restructured Chinese industry since WTO accession is more consolidated and leaner, with clearly expressed ambitions to rival (and perhaps dwarf) existing TTCs. In 2014, former Vice Premier of China Zeng Peiyan signalled a shift in Chinese economic development strategy: ‘We have shifted from an external demand-driven economy to a domestic demand-driven economy. Domestic consumption is now the most important driver of our development’ (as quoted in Canton, 2015). However, structural imbalances in the Chinese economy are predicted to bring instability and downward domestic consumption. Both will have implications for the Chinese tobacco industry. The continued efforts, by existing TTCs and other Asian tobacco companies, on penetrating this vast market suggests some potential for them to shift market share while Chinese smoking prevalence rates remain buoyant. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) implementation in China remains politically vulnerable, and weakened by inconsistent, at times half-hearted enforcement at the municipal and provincial levels (Jin, 2012; Martin, 2014). Nevertheless, should there be a downward trend in smoking rates in China, domestic companies are well-positioned to follow JTI and KT&G, with more efficient production for export, flagship brands and a growing vertical portfolio of operations abroad (from leaf to distribution). Industry sources speculate that CNTC may be grooming promising firms (such as Hongyun Honghe) for public listing (Anon, 2003).

The imminent globalisation of TTL and TTM, in contrast, is less likely. The companies can be more accurately described as regional tobacco companies at best. They have expressed the ambition to globalise, producing their products for overseas markets, but have so far falling far short of functional integration. Indeed, despite regularly expressed aspirations to globalise, the operations of the TTM remains largely domestically focused. It engages in a small volume of exports, to regional markets, produced in Thailand. There has been some consolidation and restructuring, to improve efficiency and productivity, but this has not gone beyond domestic operations. The TTM is not involved with operations abroad at the time of writing. Amid ongoing political instability, the longstanding privatisation of the TTM has remained stalled. TTL has been a bit more successful than TTM to date, although the case study shows that TTL’s ‘global’ strategy has so far focused almost exclusively on China. That is TTL’s exports, foreign licensing, product development, advertisement were all aimed at getting a foothold in the Chinese market. ‘This has created a high degree of dependency on the success of these initiatives, which have, so far, been hindered by poor management decisions and ongoing political tensions between Taiwan and China.’ However, TTL relative success with exporting alcohol products, suggests that that the company has growing experience and capacity to expand into foreign markets.

Discussion

While analysis to date has focused on tobacco industry globalisation by existing TTCs, limited attention to date has been given to adaptation by the tobacco industries in targeted markets. Comparative analysis of the case studies in this special issue suggests that these adaptations have prompted a new phase of tobacco industry globalisation that is currently being played out.

Three developments described in this special issue are of particular importance in this regard. First, JTI is likely to be joined by KT&G and CNTC over the next decade as TTCs from Asia. While the two companies have engaged in exporting their products for decades, their restructuring and functional integration, demonstrates a different mode of operation from the past. Second, the findings suggest that the global tobacco industry, which has been steadily consolidating into a global oligopoly dominated by a handful of TTCs since the 1960s, will see increased competition with the emergence of new TTCs. By 2008, it was reported that 50% of the world’s cigarette market, estimated at 5.6 trillion cigarettes sold annually, was under the control of the four leading TTCs. These companies (and their share of global market as reported by BAT) are PMI (16%), BAT and its associates (16%), JTI (11%) and Imperial Tobacco (6%). The remaining market share for cigarettes is held by state-monopolies operating in China, principally the CNTC (39%), the US operations of Philip Morris through Altria (3%), with all other tobacco companies accounting for the remaining 11%. If the trends described in this special issue continue, this would increase competition for remaining markets, especially in emerging economies in Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe and Africa. Third, China has been set aside in most accounts of the global tobacco industry given its hitherto domestic focus. However, rapid changes in the Chinese industry over the past decade suggest movement towards an increasingly global business strategy. If achieved, given the sheer size of the CNTC already, this would substantially alter the nature of the global tobacco industry. An outward-looking Chinese tobacco company would add several TTC-sized entities to the global tobacco industry, rather than just one, which would further intensify the competitive environment described above.

Why does tobacco industry globalisation matter to global public health? Tobacco products, regardless of where they are produced and whether they are targeted at domestic or foreign markets, invariably create adverse public health impacts. However, the emergence of new TTCs, as this special issue suggests, will mean fiercer competition, with tobacco companies jockeying for market share in an increasingly globalised industry. Economic theory suggests that increased competition pushes firms to seek greater efficiencies, improve productivity and gain advantage through product innovation. This creates downward pressures on price and intensified marketing (Taylor, Chaloupka, Gundon, & Corbett, 2000). Evidence shows that, during the expansion of existing TTCs, all of these developments encourage sustained, and even increased, rates of tobacco use.

The contributions in this special issue also raise questions about the role that governments could play in responding to the challenges outlined above, both at the domestic and the international level. It is of significance, in this regard, that the companies studied here all have a history of state-ownership and, in most cases, still are (partly) state-owned tobacco companies. It has recently been suggested by Hogg, Hill, and Collin (2016, p. 368), in their analyses of China and Thailand, that state-ownership may provide ‘a potential route via which to radically advance tobacco control’. Although we see the potential for state ownership to accelerate tobacco control (for a critical discussion see Barraclough & Morrow, 2010), much depends on the configuration of competing public policy priorities in these countries. The case studies in this special issue suggest a move towards privatisation and, hence, reduced state involvement in the tobacco industry in Asia, prompted by a desire to pursue foreign markets more effectively. The case studies also show that market opening through the signing of trade and investment agreements, and WTO membership (China and Taiwan), has forced these governments to review their tobacco monopolies. Where the state remains significantly involved (i.e. China, Taiwan and Thailand), this has been motivated by the desire to protect existing and substantial economic gains and/or fears of foreign takeover, rather than a commitment to protecting and promoting population health. As Pratt (2016) argues, what is needed foremost is recognition by Asian policy makers that the full economic costs generated by the tobacco industry far exceed its benefits. The case studies suggest that this recognition is more important to tobacco control in Asia than whether the industry is state or privately owned.

At the international level, the findings show how fuller understanding of emerging TTCs is central to effective FCTC implementation. The coming into force of the FCTC in 2005, and its adoption by 179 member states accounting for over 87% of the world’s population over the past decade, has led to the adoption of stronger national tobacco control policies worldwide (WHO, 2014). However, this special issue finds that the tobacco industry continues to evolve, as a result of globalisation, which poses particular regulatory challenges. The FCTC is an international treaty, with 180 member states of WHO becoming parties by 2016. As described by the Framework Convention Alliance, the treaty provides ‘an internationally co-ordinated response to combating the tobacco epidemic, and sets out specific steps for governments addressing tobacco use’. The FCTC remains an essential legal instrument for strengthening national tobacco control, and has some capacity to address issues that cross multiple jurisdictions. Under Article 13, for example, the treaty requires parties to ban tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (including crossborder advertising, promotion and sponsorship originating from its territory) no later than five years after entry into force. The adoption of the FCTC Protocol to Eliminate the Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products in 2012 is also a key instrument for tackling a major aspect of an increasingly globalised tobacco industry. As of January 2016, the Protocol has been ratified by 13 FCTC states parties, with forty required for it to come into effect. There remain other crossborder issues, such as the use of social media, evasion of taxation and liberalisation of tobacco markets through international trade and investment agreements, which require attention. Commitments to negotiate other FCTC protocols, on such issues as agriculture, duty free sales and the internet trade, have noticeably waned given the time and effort required to achieve the first. Meanwhile, existing and emerging TTCs are restructuring their operations to operate globally in order to minimise tax liabilities, achieve increased economies of scale, mobilise capital investment, source low-cost inputs and reach markets more readily through global production chains. It is important to recognise that TTCs have the capacity to exploit weak or non-enforcement of FCTC provisions, ambiguities or gaps in existing measures (Lee, Ling, & Glantz, 2012). Full implementation of the FCTC by all parties at the national level is thus an essential starting point to protecting and promoting population health from an increasingly globalised industry. Moreover, renewed efforts to negotiate further protocols, to address a range of crossborder challenges, remain critical. The case studies suggest that effective global tobacco governance requires collective action that goes beyond the strength and reach of national level tobacco control policies.

The case studies in this special issue draw attention to the highly variable, and lack of detailed, information available on specific tobacco companies. While US litigation has put into the public domain millions of pages of internal documents of existing TTCs, in itself falling short of a comprehensive archive, no such collections exist for emerging TTCs. Moreover, as state-owned monopolies in part or whole, in the case of CNTC, JTI, TTM and TTL, there is no obligation to publish such basic information on sales revenues, operations and market share. The public health community and regulators should continue to push for increased data disclosure. Indeed, there is a need to track the foreign activities of Asian tobacco companies, notably FDI, M&As and joint ventures, as indicators of increasing globalisation.

To develop effective global tobacco governance that can regulate TTCs at local, national and global levels, it is recommended that more detailed and comparative analysis of firm-level globalisation strategies of individual tobacco companies is needed. Historically, TTCs have achieved their expansion through both competition and cooperation. The latter has come in the form of cartels, both regional and global, which have become the subject of anti-trust measures by governments (Brandt, 2009). It remains unclear, however, how to best regulate the industry across national jurisdictions. From a public health perspective, which form of market structure is least likely to increase tobacco use?

The impact of the continued proliferation of bilateral, regional and multilateral trade and investment agreements, on the business strategies of tobacco companies, requires fuller understanding. In Asia, regional integration will deepen via the Asia-Pacific Trade Agreement (APTA), ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) and Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). Existing TTCs have established beachheads, in the Philippines, Hong Kong and other Asian countries, to enable recourse to the preferential treatment or dispute settlement mechanisms proffered by such agreements. The ‘carve out’ or exclusion of tobacco under TPP protections would mean that companies will be unable to lodge disputes against countries adopting stronger tobacco control measures (Whitman, 2015). There is also a need for regulators within those markets to consider the full costs of the liberalisation of tobacco trade and investment. Tensions between economic and public health policies can be direct amid economic globalisation (Fidler, Drager, & Lee, 2009). A fuller assessment of the social and economic costs of increased tobacco use is needed within such countries including early disability and death, health care costs, lost productivity, fire risks and opportunity costs.

Finally, further research is needed on the role of the illicit tobacco trade in the emergence of Asian TTCs. Although detailed data on patterns and volumes remain elusive, the case studies suggest that the illicit tobacco trade has been intertwined with the globalisation strategies of existing and emerging Asian TTCs. Previous analyses suggest that the illicit trade was a key part of TTC strategy to gain access to closed markets, and increase brand presence in competition with local companies and other TTCs. The illicit trade created and fuelled demand for their products over local brands or created new demand. A worldwide production and supply chain, to support the illicit tobacco trade, was created consisting of manufacturers, transit agents and consumers, and facilitated by criminal groups, government officials, military, local business leaders and local interest groups. By the 2000s, TTC control of the illicit trade began to wane, and competition began to emerge from counterfeiters and other manufacturers. The case studies provide some evidence that brands manufactured by KT&G and CNTC are being illicitly traded. Fuller understanding of the changing patterns of illicit trade, and the factors contributing to this changing landscape, are needed to inform existing customs and law enforcement efforts, as well as implementation of the FCTC Protocol upon coming into effect.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute, US National Institutes of Health [grant number R01-CA091021]. The authors are solely responsible for the contents of this paper.

Notes

JTI was formed in 1999 as the international division of Japan Tobacco (JT) following the purchase of the non-US operations of RJ Reynolds.

Section 301 was strengthened, most notably, with the adoption of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act (1988) which created Section 310 allowing unilateral US trade action against trade practices deemed unfair.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Kelley Lee http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3625-1915

Jappe Eckhardt http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8823-0905

References

- Anon (2003, April 22). Breaking up tobacco monopoly. Tobacco Journal International. Retrieved from http://www.tobaccojournal.com/Breaking_up_tobacco_monopoly.X3113.0.html [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough S., & Morrow M. (2010). The political economy of tobacco and poverty alleviation in Southeast Asia: Contradictions in the role of the state. Global Health Promotion, (S1), 40–50. doi: 10.1177/1757975909358243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt A. (2009). The cigarette century. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Canton N. (2015, November 11). China has shifted to domestic consumption-driven economy, growth to average at 6.5%. Asia House. Retrieved from http://asiahouse.org/chinas-shift-export-led-domestic-consumption-driven-economy-will-see-6-5-growth/

- Dicken P. (2011). Global shift: Mapping the changing contours of the world economy (6th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning J. H., & Lundan S. M. (2008). Multinational enterprises and the global economy (2nd ed.). London: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt J., Fang J., & Lee K. (2017). The Taiwan Tobacco and Liquor Corporation: To ‘join the ranks of global companies’. Global Public Health. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1273366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsig M., & Eckhardt J. (2015). The creation of the multilateral trade court: Design and experiential learning. World Trade Review, (S1), S13–S32. doi: 10.1017/S1474745615000130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International (2015a). Cigarettes in Japan. London: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International (2015b). Cigarettes in South Korea. London: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International (2015c). Cigarettes in Taiwan. London: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International (2015d). Cigarettes in Thailand. London: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Fang J., Sejpal N., & Lee K. (2016). The China National Tobacco Corporation: From domestic to global dragon? Global Public Health. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1241293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler D., Drager N., & Lee K. (2009). Managing the pursuit of health and wealth: The key challenges. Lancet, (9660), 325–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61775-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A., & McKee M. (2004). Moving East. How the transnational tobacco industry gained entry to the emerging markets of the former Soviet Union–part I: Establishing cigarette imports. Tobacco Control, (2), 143–150. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn T., Seffrin J., Brawley O., Grey N., & Ross H. (2010). The globalization of Tobacco use: 21 challenges for the 21st century. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, (1), 50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Promotion Administration, Republic of Taiwan (2016). Adult smoking behaviour surveillance system. Retrieved from http://tobacco.hpa.gov.tw/Show.aspx?MenuId=581

- Hogg S. L., Hill S. E., & Collin J. (2016). State-ownership of tobacco industry: A ‘fundamental conflict of interest’ or a ‘tremendous opportunity’ for tobacco control? Tobacco Control, (4), 367–372. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden C., Lee K., Gilmore A., Fooks G., & Wander N. (2010). Trade policy, health, and corporate influence: British American Tobacco and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization. International Journal of Health Services, (3), 421–441. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.3.c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japan Health Promotion and Fitness Foundation (n.d.). Adult smoking prevalence. Retrieved from http://www.health-net.or.jp/tobacco/product/pd090000.html

- Jin J. (2012, May 12). FCTC and China’s Politics of Tobacco Control. Paper presented to the 4th GLF Annual Colloquium, Princeton University. Retrieved from http://www.princeton.edu/~pcglobal/conferences/GLF/jin.pdf

- Kuznets P. W. (1988). An East Asian model of economic development: Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. Economic Development and Cultural Change, (3), S11–S43. doi: 10.1086/edcc.36.s3.1566537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., & Eckhardt J. (2016). The globalisation strategies of five Asian tobacco companies: An analytical framework. Global Public Health. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1251604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Eckhardt J., & Holden C. (2016). Tobacco industry globalization and global health governance: Towards an interdisciplinary research agenda. Palgrave Communications, , Article no. 16037, 1–12. doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2016.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Gong L., Eckhardt J., Holden C., & Lee S. Y. (2017). KT&G: From Korean monopoly to a ‘global name in the tobacco industry’. Global Public Health. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1273367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Y., Ling P., & Glantz S. (2012). The vector of the tobacco epidemic: Tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes and Control, (1), 117–129. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay J. (1992). China’s tobacco wars. Multinational Monitor, , 9–12. Retrieved from http://www.multinationalmonitor.org/hyper/issues/1992/01/mm0192_06.html [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie R., Eckhardt J., & Prastyani A. (2017). Japan Tobacco International: To ‘be the most successful and respected tobacco company in the world’. Global Public Health. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1273368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie R., Ross H., & Lee K. (2017). ‘Preparing ourselves to become an international organization’: Thailand Tobacco Monopoly’s regional and global strategies. Global Public Health. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1273369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhu R. (2013, August 7). Globalization and tobacco: Enabling healthy and sustainable trade governance. Global Policy Journal. Retrieved from http://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/07/08/2013/globalization-and-tobacco-enabling-healthy-and-sustainable-trade-governance [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. (2014, December 12). Getting rich selling cigarettes. Bloomberg. Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-12-12/the-chinese-government-is-getting-rich-selling-cigarettes

- Ministry of Health and Welfare (n.d.). Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Major results. Retrieved from https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/eng/index.do

- Pratt A. (2016). Can state ownership of the tobacco industry really advance tobacco control? Tobacco Control, (4), 365–366. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd P. (1985). Transnational corporations and the international cigarette industry. In Newfarmer R. (Ed.), Profits, progress and poverty: Case studies of international industries in Latin America (pp. 63–112). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A., Chaloupka F., Gundon E., & Corbett M. (2000). The impact of trade liberalization on tobacco Consumption. In Jha P. & Chaloupka F. (Eds.), Tobacco control in developing countries (pp. 343–364). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Commerce (n.d.). Section 301. Washington, DC: International Trade Administration; Retrieved from http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/tradedisputes-enforcement/tg_ian_002100.asp [Google Scholar]

- USTR (n.d.). Trade agreements, monitoring and enforcement. Washington, DC: US Trade Representative; Retrieved from https://ustr.gov/archive/assets/Trade_Agreements/Monitoring_Enforcement/asset_upload_file985_6885.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wen C. P., Cheng T. Y., Eriksen M. P., Tsai S. P., & Hsu C. C. (2014). The impact of the cigarette market opening in Taiwan. Tobacco Control, (S1), i4–i9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman E. (2015, October 2). Trans-pacific partnership: Tobacco ‘carve-out’ under trade deal would bar industries from suing countries for anti-tobacco regulations. International Business Tribune. Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.com/trans-pacific-partnership-tobacco-carve-out-under-trade-deal-would-bar-industries-2124973

- WHO (2011). NCD indicators: Tobacco [dataset]. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/infobase/Indicators.aspx

- WHO (2014). Global progress report on implementation of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: Author. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2015). WHO global report on trends in prevalence on tobacco smoking 2015. Geneva: Author; Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/156262/1/9789241564922_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]