Abstract

Two high-spin Fe(II) and Co(II) complexes of 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (CYCLEN) appended with four 2-amino-6-picolyl groups, denoted as [Fe(TAPC)]2+ and [Co(TAPC)]2+, are reported. These complexes demonstrate C2-symmetrical geometry from coordination of two pendents, and they are present in a single diastereomeric form in aqueous solution as shown by 1H NMR spectroscopy, and by a single-crystal X-ray structure for the Co(II) complex. A highly-shifted, but low intensity CEST (Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer) signal from NH groups is observed at −118 ppm for [Co(TAPC)]2+ at pH 6.0 and 37 °C. A higher intensity CEST peak is observed for [Fe(TAPC)]2+ which demonstrates a pH-dependent frequency shift from −72 to −79 ppm at pH 7.7 to pH 4.8, respectively, at 37 °C. This shift in the CEST peak correlates with the protonation of the unbound 2-amino-6-picolyl pendents, as suggested by UV-vis and 1H NMR spectroscopy studies at different pH values. Phantom imaging demonstrates the challenges and feasibility of using the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ agent on a low field MRI scanner. The [Fe(TAPC)]2+ complex is the first transition metal-based paraCEST agent that produces a pH-induced CEST frequency change towards the development of probes for concentration independent imaging of pH.

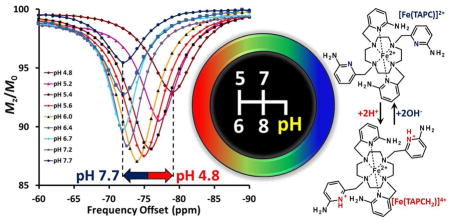

Graphical Abstract

The first Fe(II) paraCEST agent that demonstrates a pH-dependent CEST frequency shift undergoes protonation of ancillary 2-amino-6-picolyl pendent groups.

Introduction

Transition metal ion based MRI contrast agents are under development as alternatives to contrast agents that contain Ln(III) ions.1–2 Transition metal ions have a rich coordination chemistry that facilitates the design of new types of responsive contrast agents. The research presented here describes an unusual Fe(II) coordination complex that undergoes pH-dependent structural changes to produce a pH-induced shift of an exchangeable NH proton. This shift gives rise to a change in the frequency of the Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) peak. This is the first example, to the best of our knowledge, of a transition metal complex that produces a shift of CEST signal as a response to changes in pH. Such an approach is promising, given that frequency responsive MRI probes have certain advantages over intensity responsive contrast agents. In particular, a frequency responsive contrast agent does not require a correction for tissue concentration of the probe, unlike a contrast agent that responds by an increase or decrease in signal.

MRI contrast agents which are responsive to pH in the biological environment may fill a need in clinical diagnosis. MRI-based pH measurements are important for elucidation of acidosis conditions in solid tumors, as well as for renal tubular acidosis that is indicative of kidney malfunction.3–4 As a result, mapping of tissue pH by MRI may provide valuable information for disease diagnoses and the appropriate choice of therapy.5–7 The spatial resolution provided by MRI is essential to map the alterations of pH that occur at the extracellular microenvironment (pHe). Several Gd(III)-based MRI agents utilizing T1- and T2-weighted contrast have been reported,8–10 including ones based on various nanoparticle scaffolds.11–13 MRI has certain advantages over other imaging modalities used in pH measurements, such as electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR),14–15 positron emission tomography (PET)16 and in vivo optical imaging in terms of tissue depth penetration, spatial resolution and availability of instrumentation in the clinic.17–18

Our laboratory is involved in the development of paramagnetic transition metal ion complexes as responsive probes for MRI and MRS (Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy).19–20 In particular, CEST MRI is of special interest due to the intrinsic responsiveness of the exchangeable protons of the contrast agent to the environment.21 These exchangeable protons are key to producing contrast through decreasing the water proton resonance intensity.22–23 Transition metal complexes that have applications as paramagnetic CEST (paraCEST) agents may utilize many types of exchangeable protons including those on nitrogen-containing heterocyclic donors, such as pyridines,24 benzimidazoles19 and pyrazoles.25 Notably, the ionization properties of imidazole-based compounds have also been utilized in diamagnetic CEST pH-responsive imaging.26

The aminopicolyl functionalities reported here are members of a broad class of largely unexplored ligand donors with the potential for preparing new paraCEST contrast agents for imaging. A few previous reports demonstrated that amino groups produce CEST peaks for Ln(III) complexes despite their weak coordination affinity.27–28 Recent work, however, showed that there was no CEST effect when an appendant carbamate was reduced to an aminopicolyl pendent in a Ln(III) complex.29

The sensitivity of chemical exchange to physiological conditions such as pH makes paraCEST agents amenable for the development of responsive or “smart” agents.30–31 In this regard, the rate constants (kex) for the exchange of protons of the paraCEST agent and bulk water typically vary with pH. The corresponding change in the intensity of the CEST signal with pH can be used to measure pH. For example, amide-appended Ln(III) and paramagnetic transition metal(II) complexes show higher CEST intensities with pH increase, consistent with a base-catalyzed exchange mechanism.32–33 Alcohol-appended Ln(III) and Fe(II) complexes demonstrate an increase in CEST peak intensity also from base-catalyzed exchange.33–34 Utilization of Ln(III) complexes containing two types of exchangeable protons allows for ratiometric pH sensing.32 In these probes, the intensity of the amide CEST effect increases at more basic pH, while the water-based CEST effect is pH-independent.35 A second example of a ratiometric pH probe based on two sets of different amide and amine NH protons produces CEST peaks at only |Δω| ≤ 10 ppm from bulk water.36 The small shift is a significant drawback, since the CEST signals are obscured by a magnetization transfer (MT) effect in tissue when close to the bulk water frequency. All of these examples feature CEST agents that undergo a change in the intensity of the CEST effect with pH.

The first example of a paraCEST agent (Δω ≥ 50 ppm) that demonstrates a pH-responsive change in the CEST frequency (~5 ppm) is based on a Eu(III) complex appended with ionizable phenol-containing arm.37 The responsiveness of this agent is due to the deprotonation of phenol at pH values higher than 6.5, accompanied by isomerization to a quinone-like conformation. The CEST frequency shift attributed to the water ligand is most significant at pH 6.0 to 7.6, making this agent optimal for biological imaging.38 A Tb(III) analog with ionizable phenol gives a CEST peak at −550 ppm, a frequency which is well beyond the tissue MT effect.39

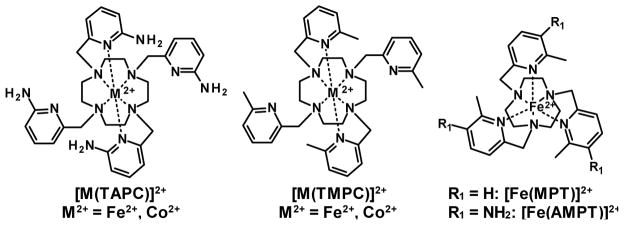

To produce the first example of a pH responsive transition metal paraCEST agent that changes CEST frequency with pH, we designed the TAPC ligand that contains exchangeable amino groups in close proximity to the metal ion center (Scheme 1). As we previously reported, NH2 groups of 3-amino-2-methyl-6-picolyl pendents produce a strong CEST effect in a paramagnetic [Fe(AMPT)]2+ complex based on 1,4,7-triazacyclononane (TACN) (Scheme 1).24 However, the paraCEST signal of this complex is only shifted 6.5 ppm from the bulk water. This small paramagnetically induced proton shift is consistent with the large distance separation between the amino group and the metal ion center, which is estimated to be > 5.2 Å as obtained for the Fe2+–H distance of the [Fe(MPT)]2+ crystal structure.40 Here, we present a Fe(II) CYCLEN-based complex, denoted as [Fe(TAPC)]2+, containing an amino functionality incorporated into the 2-amino-6-picolyl pendents. The amino groups of bound picolyl donors flank the metal binding site, placing exchangeable protons in close proximity to paramagnetic center at 3.5 Å as discussed here. Notably, this paraCEST agent is based on Fe(II), a biologically relevant transition metal ion, which holds promise as a contrast agent for imaging. A second analog based on Co(II) was also prepared.

Scheme 1.

Six-coordinate Fe(II) and Co(II) complexes.

Experimental Section

Syntheses of 6-methyl-2-phthalimidopyridine (II) and 6-bromomethyl-2-phthalimidopyridine (III) were reported before,41–42 and the optimized procedures are described in the Supporting Information.

Phthalimide-protected TAPC (IV)

The bromo-derivative III (3.9 g, 12 mmol, 4.2 equiv.) was added to an argon-purged solution of CYCLEN (0.5 g, 2.9 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and DIPEA (3.0 mL, 17 mmol, 6 equiv.) in acetonitrile (120 mL), and the reaction mixture was refluxed for 3 h (Scheme 1). The precipitate formed upon cooling to r.t. was filtered and washed with 40 mL of acetonitrile. The solids were suspended in 30 mL of water, the mixture was sonicated for 10 min, and a beige precipitate of IV was collected by centrifugation and dried under vacuum. Yield: 2.5 g, 2.2 mmol (77%). 1H NMR, 500 MHz (DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 8.01–7.94 m (8H, Ar), 7.94–7.88 m (8H, Ar), 7.80 t (4H, J = 8 Hz, Ar), 7.76 d (4H, J = 8 Hz, Ar), 7.35 d (4H, J = 8 Hz, Ar), 3.63 s (8H, 4CH2), 2.76 s (16H, 8CH2). 13C NMR, 75 MHz (DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 166.47, 160.38, 144.91, 138.60, 134.89, 131.35, 123.58, 122.81, 120.87, 60.29, 52.86. ESI-MS (m/z), calculated: 1117.4 [M + H+]. Found: 559.5 (15%) [(M + 2H+)/2], 1117.5 (100%) [M + H+] and 1139.5 (20%) [M + Na+].

TAPC ligand

The phthalimide-protected macrocycle IV (0.91 g, 0.81 mmol) was suspended in 120 mL of ethanol, and 1.2 mL of hydrazine monohydrate (1.2 g, 24 mmol) were added (Scheme 1). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 5 hours. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was dissolved in a minimal volume of acetonitrile–water (50:50, v/v) mixture and recrystallized in the fridge. The crystals were collected and redissolved in the minimal volume of methanol–water (30:70, v/v) mixture and the acidity of solution was adjusted to pH 3.5–4.0. Slow rotary evaporation gave brown precipitate, which was discarded. Further evaporation afforded white solids of TAPC ligand (×8HCl salt). Yield: 0.32 g, 0.36 mmol (44%). 1H NMR, 500 MHz (D2O, ppm): δ 7.84 t (4H, J = 8 Hz, Ar), 7.05–6.95 two d’s (8H, Ar), 4.25 s (8H, 4CH2), 3.37 s (16H, 8CH2). 13C NMR, 75 MHz (D2O, ppm): δ 156.23, 143.32, 142.83, 114.50, 112.61, 55.10, 49.02. ESI-MS (m/z), calculated: 597.4 [M + H+]. Found: 299.4 (100%) [(M + 2H+)/2], 597.4 (95%) [M + H+] and 619.5 (70%) [M + Na+].

Syntheses of complexes

The [Fe(TAPC)]Cl2 and [Co(TAPC)]Cl2 have been prepared in a similar procedure to one previously reported for the TMPC complexes.40 In a typical procedure, TAPC (0.1 mmol) was dissolved in a mixture of acetonitrile (0.4 mL) and water (0.8 mL) at pH below 4.0 followed by addition of 1 equiv. of Fe(II) or Co(II) salt. Small aliquots (1.0–2.0 μL) of 1.0 M NaOH aqueous solution were gradually added under constant stirring to adjust to pH 7.0 over one hour. The solid impurities were removed by centrifugation, and solutions were dried using a SpeedVac centrifugal evaporator. [Fe(TAPC)]Cl2 was obtained as a light beige powder (85% yield). ESI-MS: m/z 326.4 (100%) [m/2], 651.3 (50%) [m − H+], 687.2 (35%) [m + Cl−]. [Co(TAPC)]Cl2 was obtained as a light blue powder (75% yield). ESI-MS: m/z 327.9 (60%) [m/2], 654.3 (100%) [m − H+], 690.2 (20%) [m + Cl−].

Results and discussion

Ligand design and synthesis

The TAPC ligand was designed to stabilize high spin divalent Fe(II) and Co(II) complexes, to contain exchangeable NH protons, to produce symmetrical complexes with low structural fluxionality, and to provide kinetically inert complexes. The TAPC ligand was inspired by TMPC, a derivative of 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (CYCLEN) containing four 6-methyl-2-picolyl pendents. TMPC produces six-coordinate, rigid and redox-stable Fe(II) and Co(II) complexes, which are shown in Scheme 1.40 These paramagnetic complexes demonstrate hyperfine shifted proton resonances of the ligand and an effective magnetic moment (μeff) of 5.7 ± 0.1 and 6.0 ± 0.3 BM in aqueous solution, which is indicative of high spin Fe(II) and Co(II) ions, respectively. The methyl substituents flanking the pyridine N-donor groups in these Fe(II) and Co(II) ions give highly shifted 1H NMR resonances at −49.3 and −113.7 ppm, respectively, at 37 °C.40 Exchangeable amine groups were placed at the same substitution site of pyridine to gain significant dipolar shift contributions. The TAPC ligand thus contains four 2-amino-6-picolyl groups (Scheme 1). In addition, the pH dependence of the parent [Fe(TMPC)]2+ 1H NMR resonances suggested that an analogous frequency shift in the exchangeable proton resonance would be observed in the new TAPC complexes.

The synthetic route for TAPC is presented in Scheme 2. The phthalimide protection of the amino group was utilized prior to the bromination of methyl with NBS, followed by alkylation of CYCLEN and subsequent deprotection with hydrazine, which resulted in the TAPC ligand in good yield. This phthalimide protection strategy, which utilizes gentle reaction conditions, is beneficial in comparison to the pivaloyl-protecting approach, which requires harsh deprotection conditions.43 The TAPC complexes were readily formed in methanol-water (1:1) solutions according to a previously reported procedure.40 The detailed synthetic protocols are described in the Experimental Section.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of TAPC ligand and [M(TAPC)]Cl2 complexes, M2+ = Fe2+, Co2+.

Structural properties of complexes in solution

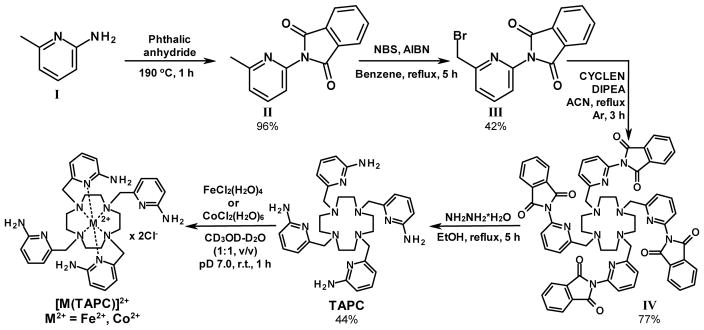

The hyperfine-shifted proton resonances of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ span the range from −75 to +290 ppm and demonstrate narrow line widths of 50–700 Hz (25 °C) in deuterium oxide as shown in Fig. 1. Together with the effective magnetic moment of μeff = 5.0 ± 0.1 BM, this 1H NMR spectrum indicates that the TAPC ligand stabilizes the high-spin Fe(II) state. Similarly, the 1H NMR resonances of [Co(TAPC)]2+, μeff = 5.2 ± 0.2 BM, are dispersed from −110 to 330 ppm (Fig. S1). Moreover, the comparison of the 1H NMR spectra of the [Co(TAPC)]2+ and [Co(TMPC)]2+, as well as [Fe(TAPC)]2+ and [Fe(TMPC)]2+ complexes clearly indicates their structural resemblance in solution due to their similar spectroscopic properties (Fig. S1, S2). The [Fe(TAPC)]2+ complex has eighteen non-exchangeable proton resonances of equivalent integrated intensities. Fourteen of these non-exchangeable proton resonances exhibit significant hyperfine shifts, while four proton resonances are found within the diamagnetic region of the spectrum (Fig. 1). This is similar to the [Fe(TMPC)]2+ complex, which produces twenty non-exchangeable proton resonances, of which eighteen have the same integrated intensities and two demonstrate three-fold higher intensities corresponding to the methyl groups (Fig. S2). The presence of one major set of proton resonances indicates that [Fe(TAPC)]2+ is stabilized in a single diastereomeric form in aqueous solution. As we have recently shown, the parent [Fe(TMPC)]2+ complex has six-coordinate C2-symmetrical geometry present in a single diastereomeric form.40 Based on comparison of the solution properties of the two complexes together with the solid state structure of [Fe(TMPC)]2+, we propose that [Fe(TAPC)]2+ also adopts six-coordinate C2-symmetrical geometry. In this geometry, the Fe(II) ion is coordinated to all four nitrogen donors of CYCLEN macrocycle and two picolyl nitrogen donors. Two 2-amino-6-picolyl groups bound to the metal ion are attached at the 1,7-amino groups of CYCLEN, and these groups are expected to bind in the cis-configuration relative to the macrocycle plane. Two other 2-amino-6-picolyl groups are not bound to the Fe(II) center, and they experience smaller paramagnetic induced shifts. These pendants produce four of the proton resonances that are in the diamagnetic region as shown in the inset of Fig. 1. However, the diastereotopic nature of the methylene group of the pendent suggests that there should be five resonances for the unbound pendents, three on the pyridine ring and two for the methylene. The fifth proton resonance is assigned as one of the fourteen highly paramagnetically shifted proton resonances. The 1H NMR spectrum of [Co(TAPC)]2+ is also consistent with a single diastereomeric C2-symmetrical structure in aqueous solution (Fig. S1A).

Figure 1.

1H NMR of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ in D2O, pD 6.8, at 25 °C. Inset shows expanded diamagnetic region. Solvent peak is labeled “S”.

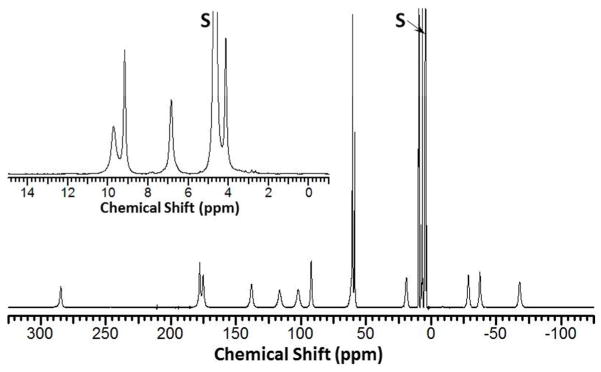

Crystal Structure

The Co(II) complex cation crystallized in the centrosymmetric P21/n space group, and the complete crystal data and structure refinement parameters are present in Table 1 and in the Supporting Information. In keeping with the symmetry of the unit cell, the enantiomeric form of the complex is present in the lattice as well. The complex cation has a total charge of +3 formed by Co2+ and H+ from one protonated pyridine atom ([Co(TAPCH)]3+). Counterions include the [CoCl4]2− anion and one chloride ion. Notably, the pyridinium ion is formed on a single unbound 2-amino-6-picolyl group.

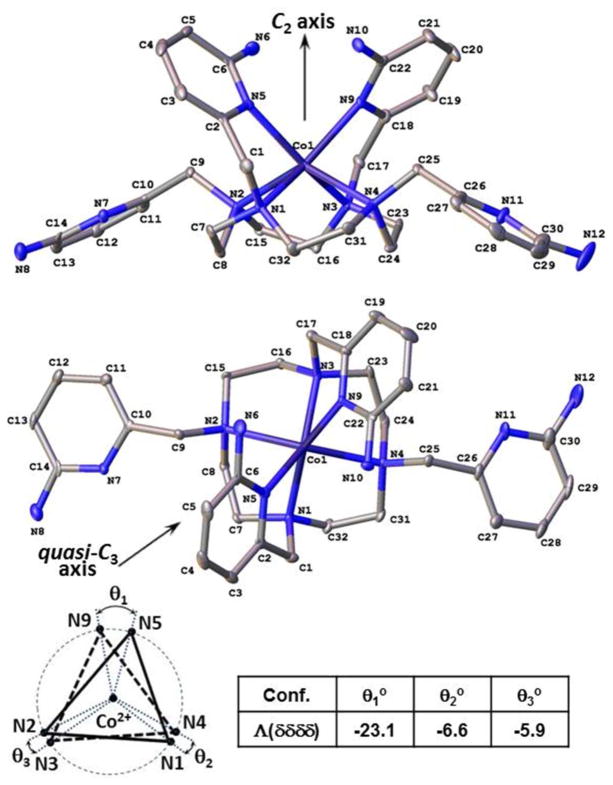

Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement for [Co(TAPCH)](CoCl4)Cl(H2O)2.

| Empirical formula | C32H49Cl5Co2N12O2 |

| Formula weight | 928.94 |

| Temperature/K | 90 |

| Crystal system | monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/n |

| a/Å | 11.7544(5) |

| b/Å | 14.9885(6) |

| c/Å | 23.5529(8) |

| α/° | 90 |

| β/° | 93.7293(12) |

| γ/° | 90 |

| Volume/Å3 | 4140.8(3) |

| Z | 4 |

| ρcalcg/cm3 | 1.490 |

| μ/mm−1 | 1.170 |

| F(000) | 1920.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3 | 0.04 × 0.02 × 0.02 |

| Radiation | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) |

| 2Θ range for data collection/° | 3.222 to 52.77 |

| Index ranges | −14 ≤ h ≤ 10, −18 ≤ k ≤ 18, −28 ≤ l ≤ 28 |

| Reflections collected | 31091 |

| Independent reflections | 8400 [Rint = 0.0469, Rsigma = 0.0472] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 8400/0/487 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.055 |

| Final R indexes [I≥2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0524, wR2 = 0.1368 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.0694, wR2 = 0.1440 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole/e Å−3 | 0.72/−1.20 |

The complex cation of [Co(TAPCH)]3+ is six-coordinate with four CYCLEN amine donors and two pyridine nitrogen atoms (Fig. 2). Two Co(II)-bound 2-amino-6-picolyl pendents at the 1,7-nitrogen atoms of CYCLEN are in the cis-configuration relative to the macrocycle plane. The complex cation demonstrates approximately C2-symmetrical structure, if the pyridinium proton is omitted from consideration. This geometry is best described as slightly distorted trigonal prismatic by using the quasi-C3 axis of the trigonal prism, which is perpendicular to the C2-symmetry axis (Fig. 2). The twist angles for each pair of apical points are calculated and shown at the bottom of Fig. 2. An overlap of [Co(TAPCH)]3+ and [Co(TMPC)]2+ crystal structures demonstrates their similarity (Fig. S3). The nitrogen atoms of the amines on the bound pendents are 3.46(6) Å away from the Co(II) center, while for the unbound pendents this distance is 7.62(5) Å. The selected bond lengths and angles are presented in Table 2. The Co2+–N1, Co2+–N2 and Co2+–N5 bond lengths are 2.176(3), 2.380(3) and 2.196(3) Å, which are consistent with the high-spin state of the Co(II) center, supporting the paramagnetic properties of this complex.40

Figure 2.

ORTEP plots of [Co(TAPCH)]3+ of Λ(δδδδ) configuration. The hydrogen atoms, counter ions and solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity, while one pyridine nitrogen atom (N7) is protonated in the model. Ellipsoids are set at 50%. Twist angles are shown for the projections of two triangles formed by three donor atoms each when viewed down the quasi-C3 axis of symmetry perpendicular to the C2-axis of symmetry.

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (deg) for [Co(TAPCH)]3+.

| [Co(TAPCH)]3+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | Bond angles (deg) | ||

| Co1–N1 | 2.176(3) | N1–Co1–N2 | 78.34(11) |

| Co1–N2 | 2.380(3) | N1–Co1–N4 | 78.07(11) |

| Co1–N3 | 2.176(3) | N1–Co1–N5 | 77.38(11) |

| Co1–N4 | 2.347(3) | N1–Co1–N9 | 152.84(11) |

| Co1–N5 | 2.196(3) | N3–Co1–N1 | 123.73(11) |

| Co1–N9 | 2.245(3) | N3–Co1–N2 | 76.59(11) |

| N3–Co1–N4 | 79.92(11) | ||

| N3–Co1–N5 | 151.07(12) | ||

| N3–Co1–N9 | 76.82(11) | ||

| N4–Co1–N2 | 128.73(10) | ||

| N5–Co1–N2 | 90.58(11) | ||

| N5–Co1–N4 | 126.94(11) | ||

| N5–Co1–N9 | 91.27(11) | ||

| N9–Co1–N2 | 126.96(11) | ||

| N9–Co1–N4 | 89.86(11) | ||

CEST Spectra

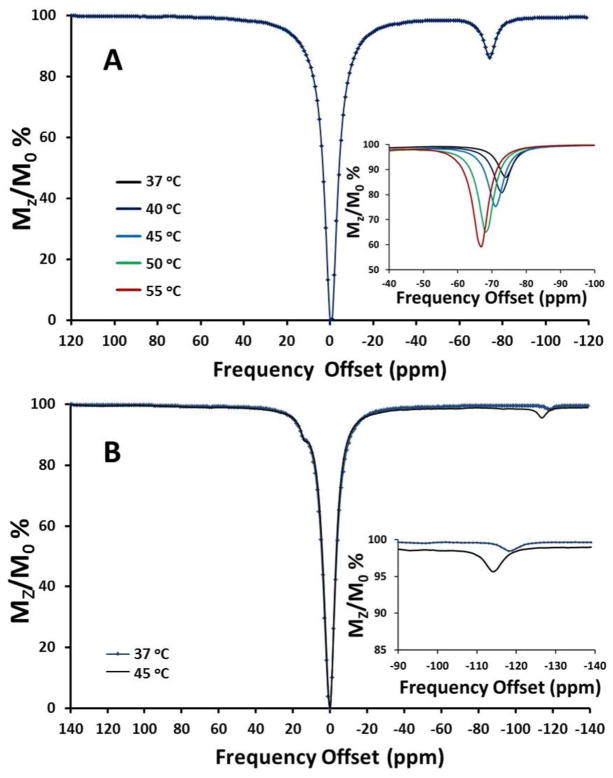

CEST contrast is produced by transfer of selectively saturated spins from the CEST agent, such as exchangeable NH protons of TAPC, to protons of bulk water. The bulk water signal decreases upon exchange with the saturated spins, and this provides a mechanism for producing an on/off contrast switch controlled by the presaturation pulse frequency.21 A CEST spectrum is plotted as a percent decrease in water proton intensity as a function of presaturation pulse frequency. Both Fe(II) and Co(II) complexes of TAPC demonstrate highly-shifted CEST peaks under slightly acidic conditions (Fig. 3). A 10 mM [Fe(TAPC)]Cl2 solution produced a 14% CEST effect at −74 ppm from bulk water at pH 6.0 and 37 °C (B1 = 24 μT, 4 s pre-saturation pulse), as shown in Fig. 3A. A comparison of the 1H NMR spectra of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ in D2O and H2O at 25 °C demonstrates exchangeable protons at −78 ppm from bulk water at 25 °C (Fig. S4). Given the temperature dependence of hyperfine shifts, this data suggests that the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ CEST peak at 37 °C arises from the NH protons. The [Fe(TAPC)]2+ CEST peak increases to 41% when temperature is increased to 55 °C as shown in the inset of Fig. 3A. The [Co(TAPC)]2+ CEST effect is significantly weaker, and it is observed only at high complex concentrations at elevated temperature as shown in Fig. 3B. Notably, one highly-shifted [Co(TAPC)]2+ CEST effect (4.4%) is observed at −114 ppm (45 °C), and another CEST signal is found at 14 ppm from bulk water. This indicates that two different exchangeable pools are present in this complex. The highly-shifted CEST peak is assigned to the NH protons of the Co(II)-coordinated 2-amino-6-picolyl pendents, while the less shifted CEST peak is assigned to the unbound 2-amino-6-picolyl groups. No enhancement of the [Co(TAPC)]2+ CEST signal was found at pH 5.5 or pH 7.2 (Fig. S5), in comparison to pH 6.0 (Fig. 3B). Given the low intensity of the [Co(TAPC)]2+ CEST peak, further studies were carried out only on the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ complex.

Figure 3.

The CEST effect of A) 10 mM [Fe(TAPC)]2+ at 37 °C and B) 26 mM [Co(TAPC)]2+ at 37 °C and 45 °C in 20 mM MES, pH 6.0, 100 mM NaCl, B1 = 24 μT, 4 s presaturation pulse. Insets show expanded temperature dependent CEST effects of 10 mM [Fe(TAPC)]2+ and 26 mM [Co(TAPC)]2+.

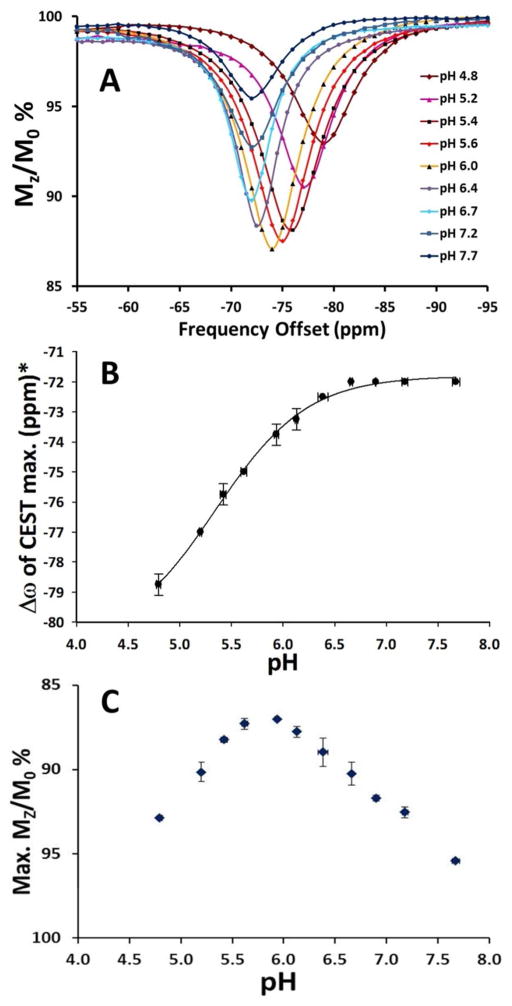

Both the intensity and position of the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ CEST signal are sensitive to pH as shown in Fig. 4A. No detectable change in the CEST peak frequency (Δω) is observed at pH 7.7 to pH 6.7. However, at conditions more acidic than pH 6.7, the CEST peak shifts away from bulk water (Fig. 4B) and the values of Δω change monotonically from −72 ppm at pH 6.7 to −79 ppm at pH 4.8 and 37 °C. Notably, such a sigmoidal type dependence of CEST on pH (Eq. S3) indicates an ionization process in [Fe(TAPC)]2+ (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, two nearly linear regions of the Δω dependence on pH allow for the linear correlation between them (Fig. S6). In addition, the CEST peak increases in intensity from pH 7.7 to 6.0 then decreases in intensity as the pH is further lowered (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

A) The pH-dependence of the 10 mM [Fe(TAPC)]2+ CEST. B) The dependence of exchange frequency Δω (ppm) of CEST maxima on pH of solution. The solid line represents fit to sigmoidal function (Eq. S3). C) The pH-dependence of CEST maxima. *-The maximum values of CEST are taken at various Δω (ppm) for pH 4.8 to pH 7.7. Conditions: 10 mM [Fe(TAPC)]2+, 20 mM HEPES/MES, 100 mM NaCl, B1 = 24 μT, 4 s presaturation pulse, 37 °C.

To better interpret these trends, the exchange rate constant (kex) of the amino protons were determined by using the Omega plot method (Fig. S7, S8).34 A rate constant for proton exchange at pH 7.7 of 1700 s−1 was obtained. Further experiments showed that exchange rate constants have a shallow dependence on pH with an increase in rate constant from pH 7.7 to 6.0 as shown in Fig. S7B. This pH trend is consistent with acid catalysed exchange as reported previously for amino groups.28 Notably, the CEST peak intensity decreases and the peak position shifts as pH is further decreased from pH 6.0 to 4.8. This trend is attributed to the formation of a new more highly protonated species. This protonated species present at acidic pH is further studied by using UV-vis spectroscopy and by NMR spectroscopy as described below. As a function of temperature, the exchange rate constant steadily increases as temperature is increased from 37 °C (1800 s−1) to 55 °C (2800 s−1) as shown in Fig. S8. This data corresponds to an increase of CEST signal at the elevated temperatures (Fig. 3A, S9). Notably, the relatively large chemical shift of the exchangeable NH protons from bulk water (Δω) allows for a large rate constant without producing exchange broadening of the CEST peak.

To further study the effect of pH and different conditions, the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ CEST effect was studied in buffers comprised of different ions at various pH values. Notably, the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ CEST effect was altered only slightly by the different anions. As shown in Figures S10 and S11, the CEST effect has similar intensity in MES, HEPES and phosphate buffers (PO43−) at similar pH values over a period of 24 hours. This is an important result, because the CEST signal of 10 mM [Fe(TAPC)]2+ is not significantly affected by 20 mM phosphate over 12 hours, which is present in biological systems in up to 0.4 mM concentrations. Moreover, as shown by 1H NMR and CEST studies, [Fe(TAPC)]2+ shows little kinetic dissociation under acidic conditions of pH 3.4 ± 0.2 (Fig. S12), as well as in the presence of biologically relevant anions, such as PO43−, CO32− and Cl− with 16% and 8% dissociation over 24 hours, respectively (Figures S12, S13 and Table S1). These data show that the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ complex has some degree of kinetic inertness, although not as inert as an Fe(II) complex of a CYCLEN derivative that contains four bound pendents.44

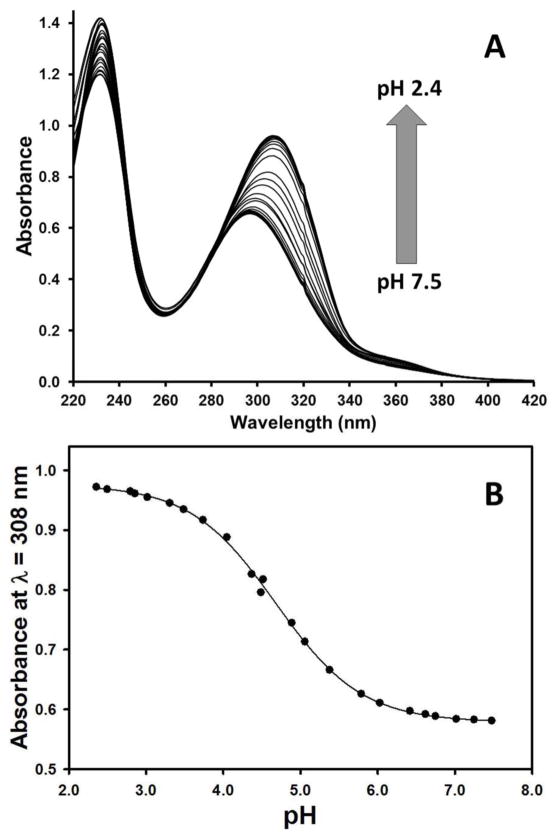

UV-vis spectroscopy studies

In order to better understand the protonation of the complex as a function of pH, the UV-visible spectra of the pyridine groups were monitored. Absorbance spectra of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ solutions at various pH values are presented in Fig. 5A. A broad absorbance band with a maximum at about 300 nm is assigned to the pyridine pendent π–π* ligand-centered transitions. No significant absorbance changes are detected when the solution is acidified from pH 7.5 to pH 6.5. When the pH of the solution is further decreased from pH 6.5 to pH 2.4, a red shift of the π–π* absorbance band from 296 to 308 nm is observed, while the intensity of this absorbance band increases. This pH-dependent absorbance change is reversible, and there is an isosbestic point at 281 nm, suggesting a pH-dependent interconversion between species of different protonation states in solution at 37 °C. Fitting of the pH-dependent absorbance intensity of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ at λ = 308 nm gives a pKa 4.68 ± 0.02 (Fig. 5B). This data is consistent with the protonation of the amino-picolyl groups as the source of the CEST peak shift. This data does not enable us to distinguish which amino-picolyl groups are protonated. However, the fact that the absorbance change from pH 6.5 to 4.0 is twice that of a simple 2-amino-6-methylpyridine model compound for solutions of the same concentration suggests that there are two amino-picolyl groups that become protonated over this pH range. Note that it is unlikely that the unbound picolyl groups would protonate outside of the pH range studied here. Thus the good fit of the titration data to an equation with a single ionization event is most consistent with the pKa values of the two pendents being very close to each other. The reversible nature of the protonation as shown by an absorbance titration also supports the involvement of the pendent amino-picolyl groups as it is difficult to imagine that protonation of the coordinated groups would leave the complex intact.

Figure 5.

A) The pH-dependence of the UV-vis spectra of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ and B) pH-dependence of the absorbance intensity of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ at λ = 308 nm with a curve showing a fit of the data to Eq. S4 that gives pKa 4.68 ± 0.02. Conditions: 38 μM [Fe(TAPC)]2+, 2 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl in H2O at 37 °C.

The pH dependent UV-vis properties of 2-amino-6-methylpyridine as a model compound were studied for comparison. Similar to [Fe(TAPC)]2+, an increase of absorbance, as well as a red shift from 292 to 304 nm is observed when a solution of the model pendent group was acidified from pH 7.7 to pH 3.9 (Fig. S14A). Fitting of the pH-dependent absorbance intensity of 2-amino-6-methylpyridine at λ = 304 nm gives a pKa of 7.12 ± 0.06. (Fig. S14B). Interestingly, the difference in the pKa values of a free 2-amino-6-methylpyridine and the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ unbound pendents is 2.4 pH units. The higher acidity of the protonated pendents of the complex compared to that of the simple amino-pyridine is consistent with the large cationic charge on the complex.

NMR spectroscopy studies of pH-induced structural changes

The proton NMR spectrum of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ changes in response to pH, with selective effects on a few resonances. The linewidths (50–700 Hz) and intensities of the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ proton resonances remain unchanged in D2O solutions in the range of pD 8.3 to pD 6.1 (Fig. S15). However, at more acidic values (pD 5.8 to 5.1), there is a marked effect on a few of the paramagnetically shifted resonances, in particular those in the range of 50–100 ppm and in diamagnetic region (Fig. S16). These resonances shift or broaden into the baseline. As shown more clearly in Fig. S17 for pD 5.1 versus pD 7.3, most of the other resonances demonstrate at least some pH-induced shift (< 5 ppm). The four resonances in the diamagnetic region of the spectrum are also affected by a decrease in pD at the most acidic values of pD 5.1–6.5 (Fig. S16B). However, chemical shift differences are smaller for these resonances that have little paramagnetic contribution (ca 0.5 ppm). These chemical shift differences are analogous to those observed in the protonation of the model compound, 2-amino-6-methylpyridine at values close to its pKa 7.71 ± 0.03 in D2O (Fig. S18, S19).45 The pH-dependence of the resonances is thus most consistent with protonation of the complex to give minor changes in overall conformation. Unfortunately, the paramagnetic nature of the complex makes it difficult to assign proton resonances by using standard NMR spectroscopy methods. Theoretical calculations that predict the paramagnetic proton chemical shifts are challenging to do given the large contributions from both contact and pseudocontact shifts, although recent success on Fe(II) complexes has recently been reported.46 Most notably, the structural changes of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ in solution are completely reversible. No oxidation to Fe(III), or dissociation of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ is observed by 1H NMR spectra consecutively taken at pD 8.3, pD 5.1 and pD 6.4 (Fig. S20). This indicates that the inner-sphere six-coordinate geometry produced by N-donors of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ is not disturbed at acidic conditions. This data and that of the UV-vis spectral changes are most consistent with protonation of unbound 2-amino-6-picolyl pendants.

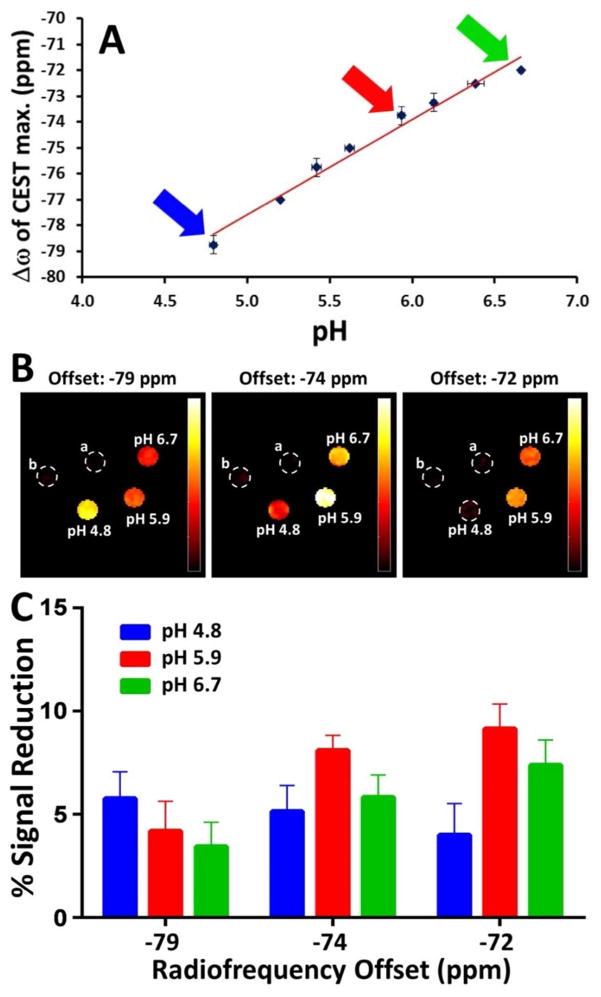

Phantom imaging

Finally, the possibility of using CEST peak position for registration of pH was studied further for [Fe(TAPC)]2+. Notably, over the pH range of 4.8 to 6.7, there is a nearly linear dependence of CEST peak position with pH, although the shift in position is small (Fig. 6A). While these small chemical shift differences are readily distinguished on a high field NMR spectrometer (Fig. 4), analogous studies on a MRI scanner of lower field strength are more challenging. The phantom images of the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ solutions at pH 4.8, 5.9 and 6.7 were obtained after applying a presaturation pulse at −79, −74 or −72 ppm, respectively (Fig. 6B). The intensity of CEST obtained at 4.7 T by MRI (Fig. 6C) correlates with the shift of the optimal radiofrequency for a given pH at 11.7 T by NMR (Fig. 6A). However, the intensity of phantoms at pH 5.9 and 6.7 are nearly indistinguishable within error upon saturation at −72 ppm (Fig. 6B & 6C). Thus no further efforts were made to study CEST peak position as a function of pH on the MRI scanner. The difficulty in resolving the change in the CEST signal with pH is attributed to the poorer precision and spectral resolution on the 4.7 T MRI scanner.

Figure 6.

A) The dependence of exchange frequency Δω (ppm) of CEST maxima on pH at 37 °C obtained on a NMR spectrometer at 11.7 T. Red line represents linear fit, R2 = 0.978. Colored arrows show radiofrequency of interest for imaging pH 4.8, 5.9 and 6.7. B) The CEST images of phantoms at 37 °C on an MRI 4.7 T scanner. Solutions of 12 mM [Fe(TAPC)]2+ in 100 mM NaCl and 20 mM MES buffer of pH 4.8, 5.9 and 6.7 were irradiated at −79, −74 and −72 ppm. The dotted circles represent the tubes containing a) water and b) 20 mM MES buffer, 100 mM NaCl. C) The bar graph represents % CEST at three pH values when samples are irradiated at different frequency offsets as in B).

Interestingly, the pH responsive Eu(III) paraCEST agent reported by Sherry et al had a similar CEST peak shift of 6 ppm with pH.37–38 Rather than scan through a range of radiofrequencies for the presaturation pulse to map out the peak shape, studies with the Eu(III) complex used a ratio of the CEST intensity at two different frequencies. The CEST ratio varied linearly with pH as shown both a NMR spectrometer at 9.4 T and on a high field MRI scanner at 9.4 T. In contrast, our work suggests that other approaches may be more viable, especially on low field MRI scanners. For example, paraCEST agents with two CEST peaks, each with a different pH dependent intensity, were successfully used for ratiometric registration of pH both at 11.7 T and on a 4.7 T MRI scanner.47–49 This highlights some of the challenges of using shift dependent CEST agents for pH mapping. Notably, the deconvolution of the CEST shift with both temperature and pH is another challenge.

Summary and Conclusions

The versatile chemistry of high spin Fe(II) facilitates the design of complexes of different coordination numbers and geometries. Remarkably, even complexes based on the same tetraazamacrocycle may be either eight-coordinate33, 47 or six-coordinate.50 The coordination sphere of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ with two bound pendents and two additional pendents provides an unusual pH response. The position of the CEST peak shifts monotonically under acidic conditions at values less than pH 6.7. This change in Δω is attributed to subtle structural changes of the complex, which in turn, are caused by protonation of the unbound 2-amino-6-picolyl pendents of the TAPC ligand, as supported by UV-vis spectroscopy, 1H NMR spectroscopy and by the observation of the [Co(TAPCH)]3+ complex cation in solid state. The structural changes that occur upon protonation may involve a change in orientation of the pendents. For example, the protonated 2-amino-6-picolyl pendents would likely be oriented to avoid any interaction with the cationic Fe(II) center. Notably, a crystal structure of an tetrakis(pyridyl) appendant CYCLEN complex of Fe(II) has two bound pendents and two additional pendents which are too far from the Fe(II) center to be considered to be within a typical bonding distance, but yet are oriented towards the Fe(II) center.50

The rate constant for exchange of the amino protons of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ with water is 1900 s−1 at 37 °C and pH 6.0. This relatively large rate constant is typical of amine groups including that of an uncoordinated aliphatic NH2 group in a lanthanide complex (2100 s−1 at pH 7.4)28 and a free amino group of acetyl-Lys-NH2 (4000 s−1 at pH 7.0).51 For [Fe(TAPC)]2+, the proton exchange rate constant is nearly independent of pH over the range of 4.8 to 7.7 with slightly higher values at 6.0 that correspond to higher CEST peak intensity, whereas a modest (two-fold) difference in rate constant is observed for that of the aliphatic amino group.28 In contrast, the rate constants for exchange of NH protons of amide pendents are low, ranging from 300 to 800 s−1 at neutral pH.20 ParaCEST agents with amide pendents generally undergo base-catalyzed proton exchange with CEST peak intensity and corresponding exchange rate constants increasing with pH.

The basis for the relatively low intensity of the CEST effect for both the Fe(II) and Co(II) complexes is not clear at this juncture. Under similar pH 6.9 conditions at 37 °C, a Co(II) complex with three pyrazole pendents gives a CEST effect of 24% for three NH protons25 in comparison to the 8% observed here for [Fe(TAPC)]2+ and 2% for [Co(TAPC)]2+. This is despite the fact that there are four equivalent exchangeable NH protons for the latter two complexes. For [Co(TAPC)]2+, all proton resonances are broadened slightly, consistent with either a fluxional process or a less than optimal electronic relaxation time.40 Previous work in our laboratory has shown that complexes that have broad proton resonances due to either dynamic processes or electronic relaxation times that are unfavorable for paraCEST,19 such as found for certain Ni(II) complexes, produce less intense paraCEST peaks.52 However, the [Fe(TAPC)]2+ non-exchangeable proton resonances are not broadened, leading us to suggest that the inherently lower CEST effect for the amino group, as also observed for a Ln(III) derivative is characteristic of this functionality.27–29, 36 Efforts to better understand the factors that contribute to the shape and intensity of the CEST peak are needed. Notably, the Bloch equations that have been used to model CEST peak intensity for Ln(III) paraCEST agents do not take into account properties such as differences in electronic relaxation times for different metal ion geometries or dynamic solution processes that would affect CEST peak intensity.53

The [Fe(TAPC)]2+ CEST peak dependence changes most over the pH range of pH 4.6 to 6.5. At the higher pH range, these agents might be useful for imaging of acidosis in tumors (pHe 6.6).54 Alternatively, the shift might be tuned by modulating the pKa of the unbound pendent groups, which are responsible for the pH-induced shift of the CEST exchange frequency. Thus, additional methyl, or other electron-donating substituents on the picolyl pendents may be useful to give values of pKa 6.6 – pKa 7.0 which are optimal for imaging acidosis. Overall, the unusual structural properties of TAPC complexes provide a promising platform for the development of responsive CEST agents. Phantom imaging experiments suggest that the pH-induced Δω shift of [Fe(TAPC)]2+ CEST (6 ppm) will make imaging on low field instruments challenging. Further structural optimization using pyridine substitution should be carried out to improve the pH-responsive shift. Our work demonstrates that N-containing donor groups suitable for coordination with transition metals ions provide peculiar intrinsic pH-responsiveness, which is unusual for Ln(III)-based contrast agents. Moreover, we present a new 2-amino-6-picolyl functionality for paraCEST MR imaging with transition metal ions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

JRM and JAS thank the NIH (CA175858) and JRM thanks the NSF (CHE-1310374) for support of this work.

Footnotes

The supporting information is free of charge on the ACS publications website at DOI xx. Experimental details including NMR spectra, CEST spectra, Omega plots to obtain exchange rate constants and synthetic procedures are available.

References

- 1.Drahoš B, Lukeš I, Toth E. Manganese(II) Complexes as Potential Contrast Agents for MRI. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2012;(12):1975–1986. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuźnik N, Wyskocka M. Iron(III) Contrast Agent Candidates for MRI: a Survey of the Structure–Effect Relationship in the Last 15 Years of Studies. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2016;(4):445–458. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashim AI, Zhang X, Wojtkowiak JW, Martinez GV, Gillies RJ. Imaging pH and Metastasis. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(6):582–591. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raghunand N, Howison C, Sherry AD, Zhang S, Gillies RJ. Renal and Systemic pH Imaging by Contrast-Enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(2):249–257. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillies RJ, Raghunand N, Garcia-Martin ML, Gatenby RA. pH Imaging. A Review of pH Measurement Methods and Applications in Cancers. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2004;23(5):57–64. doi: 10.1109/memb.2004.1360409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey KM, Wojtkowiak JW, Cornnell HH, Ribeiro MC, Balagurunathan Y, Hashim AI, Gillies RJ. Mechanisms of Buffer Therapy Resistance. Neoplasia. 2014;16(4):354–364.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pilon-Thomas S, Kodumudi KN, El-Kenawi AE, Russell S, Weber AM, Luddy K, Damaghi M, Wojtkowiak JW, Mule JJ, Ibrahim-Hashim A, Gillies RJ. Neutralization of Tumor Acidity Improves Antitumor Responses to Immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2016;76(6):1381–1390. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang S, Wu K, Sherry AD. A Novel pH-Sensitive MRI Contrast Agent. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1999;38(21):3192–3194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frullano L, Catana C, Benner T, Sherry AD, Caravan P. Bimodal MR–PET Agent for Quantitative pH Imaging. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49(13):2382–2384. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez GV, Zhang X, Garcia-Martin ML, Morse DL, Woods M, Sherry AD, Gillies RJ. Imaging the Extracellular pH of Tumors by MRI after Injection of a Single Cocktail of T1 and T2 Contrast Agents. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(10):1380–1391. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okada S, Mizukami S, Kikuchi K. Switchable MRI Contrast Agents Based on Morphological Changes of pH-Responsive Polymers. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20(2):769–774. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okada S, Mizukami S, Sakata T, Matsumura Y, Yoshioka Y, Kikuchi K. Ratiometric MRI Sensors Based on Core–Shell Nanoparticles for Quantitative pH Imaging. Adv Mater. 2014;26(19):2989–2992. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhuiyan MPI, Aryal MP, Janic B, Karki K, Varma NRS, Ewing JR, Arbab AS, Ali MM. Concentration-Independent MRI of pH with a Dendrimer-Based pH-Responsive Nanoprobe. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2015;10(6):481–486. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khramtsov VV, Grigor’ev IA, Foster MA, Lurie DJ, Nicholson I. Biological Applications of Spin pH Probes. Cell Mol Biol. 2000;46(8):1361–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bobko AA, Eubank TD, Voorhees JL, Efimova OV, Kirilyuk IA, Petryakov S, Trofimiov DG, Marsh CB, Zweier JL, Grigor’ev IA, Samouilov A, Khramtsov VV. In Vivo Monitoring of pH, Redox Status, and Glutathione Using L-band EPR for Assessment of Therapeutic Effectiveness in Solid Tumors. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(6):1827–1836. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vāvere AL, Biddlecombe GB, Spees WM, Garbow JR, Wijesinghe D, Andreev OA, Engelman DM, Reshetnyak YK, Lewis JS. A Novel Technology for the Imaging of Acidic Prostate Tumors by Positron Emission Tomography. Cancer Res. 2009;69(10):4510–4516. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mordon S, Devoisselle JM, Maunoury V. In Vivo pH Measurement and Imaging of Tumor Tissue Using a pH-Sensitive Fluorescent Probe (5,6-Carboxyfluorescein): Instrumental and Experimental Studies. Photochem Photobiol. 1994;60(3):274–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassan M, Riley J, Chernomordik V, Smith P, Pursley R, Lee SB, Capala J, Gandjbakhche AH. Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging System for in vivo Studies. Mol Imaging. 2007;6(4):229–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsitovich PB, Morrow JR. Macrocyclic Ligands for Fe(II) ParaCEST and Chemical Shift MRI Contrast Agents. Inorg Chim Acta. 2012;393:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorazio SJ, Olatunde AO, Tsitovich PB, Morrow JR. Comparison of Divalent Transition Metal Ion ParaCEST MRI Contrast Agents. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2013;19(2):191–205. doi: 10.1007/s00775-013-1059-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A New Class of Contrast Agents for MRI Based on Proton Chemical Exchange Dependent Saturation Transfer (CEST) J Magn Reson. 2000;143(1):79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viswanathan S, Kovacs Z, Green KN, Ratnakar SJ, Sherry AD. Alternatives to Gadolinium-based MRI Metal Chelates. Chem Rev. 2010;110(5):2960–3018. doi: 10.1021/cr900284a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Zijl PCM, Yadav NN. Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST): What is in a Name and What Isn’t? Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(4):927–948. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorazio SJ, Tsitovich PB, Siters KE, Spernyak JA, Morrow JR. Iron(II) PARACEST MRI Contrast Agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(36):14154–14156. doi: 10.1021/ja204297z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsitovich PB, Spernyak JA, Morrow JR. A Redox-Activated MRI Contrast Agent that Switches Between Paramagnetic and Diamagnetic States. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52(52):13997–14000. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang X, Song X, Ray Banerjee S, Li Y, Byun Y, Liu G, Bhujwalla ZM, Pomper MG, McMahon MT. Developing Imidazoles as CEST MRI pH Sensors. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krchova T, Kotek J, Jirak D, Havličkova J, Cisařova I, Hermann P. Lanthanide(III) Complexes of Aminoethyl-DO3A as PARACEST Contrast Agents Based on Decoordination of the Weakly Bound Amino Group. Dalton Trans. 2013;42(44):15735–15747. doi: 10.1039/c3dt52031e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chauvin T, Torres S, Rosseto R, Kotek J, Badet B, Durand P, Toth E. Lanthanide(III) Complexes That Contain a Self-Immolative Arm: Potential Enzyme Responsive Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Chem Eur J. 2012;18(5):1408–1418. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He J, Bonnet CS, Eliseeva SV, Lacerda S, Chauvin T, Retailleau P, Szeremeta F, Badet B, Petoud S, Toth E, Durand P. Prototypes of Lanthanide(III) Agents Responsive to Enzymatic Activities in Three Complementary Imaging Modalities: Visible/Near-Infrared Luminescence, PARACEST-, and T1-MRI. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(9):2913–2916. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Lubag AJM, Malloy CR, Martinez GV, Gillies RJ, Sherry AD. Responsive MRI Agents for Sensing Metabolism in Vivo. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42(7):948–957. doi: 10.1021/ar800237f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hingorani DV, Bernstein AS, Pagel MD. A Review of Responsive MRI Contrast Agents: 2005–2014. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2015;10(4):245–265. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aime S, Barge A, Delli Castelli D, Fedeli F, Mortillaro A, Nielsen FU, Terreno E. Paramagnetic Lanthanide(III) Complexes as pH-Sensitive Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) Contrast Agents for MRI Applications. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(4):639–648. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorazio SJ, Morrow JR. Iron(II) Complexes Containing Octadentate Tetraazamacrocycles as ParaCEST Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents. Inorg Chem. 2012;51(14):7448–7450. doi: 10.1021/ic301001u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dixon WT, Ren J, Lubag AJM, Ratnakar J, Vinogradov E, Hancu I, Lenkinski RE, Sherry AD. A Concentration-Independent Method to Measure Exchange Rates in PARACEST Agents. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(3):625–632. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aime S, Delli Castelli D, Terreno E. Novel pH-Reporter MRI Contrast Agents. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;114(22):4510–4512. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021115)41:22<4334::AID-ANIE4334>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheth VR, Liu G, Li Y, Pagel MD. Improved pH Measurements with a Single PARACEST MRI Contrast Agent. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2012;7(1):26–34. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Y, Soesbe TC, Kiefer GE, Zhao P, Sherry AD. A Responsive Europium(III) Chelate That Provides a Direct Readout of pH by MRI. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(40):14002–14003. doi: 10.1021/ja106018n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Y, Zhang S, Soesbe TC, Yu J, Vinogradov E, Lenkinski RE, Sherry AD. pH Imaging of Mouse Kidneys In Vivo Using a Frequency-dependent ParaCEST Agent. Magn Reson Med. 2015;75(6):2432–2441. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Wu Y, Soesbe TC, Yu J, Zhao P, Kiefer GE, Sherry AD. A pH-Responsive MRI Agent that Can Be Activated Beyond the Tissue Magnetization Transfer Window. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54(30):8662–8664. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsitovich PB, Cox JM, Benedict JB, Morrow JR. Six-coordinate Iron(II) and Cobalt(II) paraSHIFT Agents for Measuring Temperature by Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Inorg Chem. 2016;55(2):700–716. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Congreve M, Aharony D, Albert J, Callaghan O, Campbell J, Carr RAE, Chessari G, Cowan S, Edwards PD, Frederickson M, McMenamin R, Murray CW, Patel S, Wallis N. Application of Fragment Screening by X-ray Crystallography to the Discovery of Aminopyridines as Inhibitors of β-Secretase. J Med Chem. 2007;50(6):1124–1132. doi: 10.1021/jm061197u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malamas MS, Barnes K, Hui Y, Johnson M, Lovering F, Condon J, Fobare W, Solvibile W, Turner J, Hu Y, Manas ES, Fan K, Olland A, Chopra R, Bard J, Pangalos MN, Reinhart P, Robichaud AJ. Novel Pyrrolyl 2-Aminopyridines as Potent and Selective Human β-Secretase (BACE1) Inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20(7):2068–2073. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wada A, Honda Y, Yamaguchi S, Nagatomo S, Kitagawa T, Jitsukawa K, Masuda H. Steric and Hydrogen-Bonding Effects on the Stability of Copper Complexes with Small Molecules. Inorg Chem. 2004;43(18):5725–5735. doi: 10.1021/ic0496572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dorazio SJ, Tsitovich PB, Gardina SA, Morrow JR. The Reactivity of Macrocyclic Fe(II) ParaCEST MRI Contrast Agents Towards Biologically Relevant Anions, Cations, Oxygen or Peroxide. J Inorg Biochem. 2012;117:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salomaa P, Schaleger LL, Long FA. Solvent Deuterium Isotope Effects on Acid-Base Equilibria. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin B, Autschbach J. Kohn-Sham Calculations of NMR Shifts for Paramagnetic 3d Metal Complexes: Protocols, Delocalization Error, and the Curious Amide Proton Shifts of a High-Spin Iron(II) Macrocycle Complex. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2016;18(31):21051–21068. doi: 10.1039/c5cp07667f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olatunde AO, Bond CJ, Dorazio SJ, Cox JM, Benedict JB, Daddario MD, Spernyak JA, Morrow JR. Six, Seven or Eight Coordinate FeII, CoII or NiII Complexes of Amide-Appended Tetraazamacrocycles for ParaCEST Thermometry. Chem Eur J. 2015;21(50):18290–18300. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delli Castelli D, Terreno E, Aime S. YbIII-HPDO3A: A Dual pH- and Temperature-Responsive CEST Agent. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50(8):1798–1800. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delli Castelli D, Ferrauto G, Cutrin JC, Terreno E, Aime S. In Vivo Maps of Extracellular pH in Murine Melanoma by CEST–MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(1):326–332. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bu X-H, Lu S-L, Zhang R-H, Liu H, Zhu H-P, Liu Q-T. Synthesis, Characterization and Crystal Structures of the Cobalt(II) and Iron(II) Complexes with an Octadentate Ligand, 1,4,7,10-Tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (L), [ML]2+ Polyhedron. 2000;19(4):431–435. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liepinsh E, Otting G. Proton Exchange Rates from Amino Acid Side Chains–Implications for Image Contrast. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35(1):30–42. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olatunde AO, Dorazio SJ, Spernyak JA, Morrow JR. The NiCEST Approach: Nickel(II) ParaCEST MRI Contrast Agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(45):18503–18505. doi: 10.1021/ja307909x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woessner DE, Zhang S, Merritt ME, Sherry AD. Numerical Solution of the Bloch Equations Provides Insights into the Optimum Design of PARACEST Agents for MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(4):790–799. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaupel P, Kallinowski F, Okunieff P. Blood Flow, Oxygen and Nutrient Supply, and Metabolic Microenvironment of Human Tumors: A Review. Cancer Res. 1989;49(23):6449–6465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.