Abstract

Purpose

Blood glucose is routinely measured prior to 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) administration in positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to identify hyperglycemia that may affect image quality. In this study we explore the effects of blood glucose levels upon semi-quantitative standardized uptake value (SUV) measurements of target organs and tissues of interest and in particular address the relationship of blood glucose to FDG accumulation in the brain and liver.

Methods

436 FDG PET/CT consecutive studies performed for oncology staging in 229 patients (226 male) at the Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Healthcare System were reviewed. All patients had blood glucose measured (112.4 ± 34.1 mg/dL) prior to injection of 466.2 ± 51.8 MBq (12.6 ± 1.4 mCi) of FDG. SUV measurements of brain, aortic arch blood-pool, liver, and spleen were obtained at 64.5 ±10.2 min’ post-injection.

Results

We found a negative inverse relationship of brain SUV with increasing plasma glucose, levels for both absolute and normalized (either to blood-pool or liver) values. Higher blood glucose levels had a mild effect upon liver and blood-pool SUV. By contrast, spleen SUV was independent of blood glucose, but demonstrated the greatest variability (deviation on linear regression). In contrast to other tissues, liver and spleen SUV normalized to blood-pool SUV were not dependent upon blood glucose levels.

Conclusion

The effects of hyperglycemia upon FDG uptake in brain and liver, over a range of blood glucose values generally considered acceptable for clinical PET imaging, may have measurable effects on semi-quantitative image analysis.

Keywords: PERCIST, Alzheimer’s, 18F-FDG biodistribution, Hyperglycemia, PET, Quantitative imaging

1. Introduction

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) brain PET has demonstrable value in distinguishing Alzheimer disease from other forms of dementia [1,2]. Quantitative parametric imaging techniques have further improved brain PET diagnostic accuracy, interobserver agreement and reader training [2,3]. Hyperglycemia is known to influence brain FDG uptake [4,5], and consensus imaging protocols advise brain FDG PET/CT after a 4 h fast to achieve desirable blood glucose levels in the range of <160 mg/dL, as a threshold for hyperglycemia [6–8]. However, two recent studies report concern that milder degrees of hyperglycemia could potentially confound brain FDG PET/CT imaging by producing patterns of decreased cortical brain FDG uptake that could potentially mimic patterns seen in Alzheimer disease, using quantitative voxel-based parametric techniques [9,10].

For oncological staging, there is concern that acute hyperglycemia leading to competitive saturation of glucose transporters (Glut-1 and 3) may decrease the sensitivity of PET for tumor detection. Insulin stimulates upregulation of Glut-4 in muscle (heart and striated) and adipose tissues causing a shift of FDG distribution into peripheral muscle, soft tissues and fat, with lower tumor target-to-background uptake ratios. Consequently, in a fasting patient with satisfactory blood glucose at the time of FDG administration, it is assumed that FDG accumulation by organs and tissues of interest reflects underlying cellular glucose metabolism.

Several years ago (2009) Wahl et al. suggested criteria to evaluate treatment response based on metabolic information derived from PET images, as a complementary tool to the RECIST criteria used for diagnostic imaging with anatomical modalities [11]. PERCIST criteria were formulated, requiring a change in lean body mass-derived SUV of 30% within a target lesion when the liver is unchanged between two successive PET CT scans (change liver SUV is <20% or an absolute <0.3 change). If disease was present within the liver, the blood pool was recommended as a “reference” tissue for comparison with similar constraints.

In this study we examine the relationship between FDG uptake in selected organs and tissues of interest as a function of blood glucose levels at the time of FDG administration. Additionally, we evaluated other patient specific factors to better delineate variables affecting semi-quantitative FDG imaging techniques.

2. Methods

All study related activity was approved by the Ann Arbor Veterans Administration internal review board (IRB), research committee, and Radioactive Drug Research Committees (RDRC).

2.1. Patients selection

From July 1, 2015 retrospective consecutive whole body PET/CT scans (n = 229 patients) performed for oncology staging were reviewed along with any available comparisons (436 total scans). Patient medical records were reviewed for the following information: age, gender, primary tumor type, medications (in particular those known to affect glucose metabolism or neural activity), metabolic disease (thyroid disorders, diabetes, etc.), hemoglobin, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), injected FDG dose and time intervals between glucose measurements/FDG administration and initiation of subsequent imaging. Patients were excluded if they had recently taken diabetes medications or if blood glucose was above 250 mg/dL per clinical protocol. Patients were also excluded if the reason for the PET/CT was neurodegenerative disease evaluation, history of dementia, or cerebral vascular accident (CVA) either noted in the medical record or depicted on the images.

2.2. Image analysis

Sequential PET and CT imaging were performed on an integrated PET/CT scanner (Siemens Biograph T6; Siemens Medical Solutions, Hoffman Estates, IL, USA). Helical CT with 5 mm collimation from skull vertex to mid-thigh followed immediately by whole body PET at multiple overlapping bed positions. FDG-PET/CT images were co-registered and reviewed on workstations using software with fusion capability (MedImage; MedView Pty, Canton, MI, USA). SUV measurements based on body weight (SUVkg) were calculated from attenuation corrected images with regions of interest (ROI) drawn over the right hepatic lobe (if uninvolved of disease per Wahl et al.), spleen (if uninvolved of disease), mediastinal blood pool in the ascending aorta/aortic arch, bilateral basal ganglia at the level of the internal capsule, and the entire brain at the same slice as that selected for basal ganglia analysis. ROI’s were either circular/ellipsoid to best fit the anatomy with the exception of the liver, which was circular and fixed at 3 cm diameter at the approximate segment VI/VIII level per Wahl and colleagues recommendations for metabolic tumor response criteria. ROI’s in the aorta were sized to maximize measurement volume excluding vessel wall and/or atherosclerotic disease. For each ROI, maximum, mean and minimum SUVkg measurements were obtained.

2.3. Data/statistical analysis

Power analysis for an independent sample t-test was conducted for mean liver SUV of 2.2 ± 0.1 versus mean blood SUV of 1.9 ± 0.1 using an alpha of 0.05, a sample size of 225 in each group, and two tails. Based on these assumptions, the power of the estimate is 99.9%. Simple descriptive statistics were used for patient demographics. Multivariate linear regression with blood pool, liver and spleen SUVkg uptake as dependent variables and glucose and patient demographics (BMI, tumor type, diabetes status with and without medications, and injection time to imaging intervals) as the independent variable were performed. Wilks’ lambda test was used to determine the difference between the means of glucose on a combination of dependent variables (blood pool, liver and spleen SUVkg uptake). Multivariate linear regression using SUVBMI was also performed. Nonlinear regression was used to fit SUV data in the brain assuming a mono-exponential relationship. Subsequent multiple linear regression with log transformed brain SUVkg as the response variable, with the above variable as covariates was also performed.

3. Results

436 PET/CT studies performed for oncology indications in 229 in patients (3women, 226 men) were included, with an average of 3.6 studies per patient in those that had follow-up imaging (Table 1). Of these, 371 (85.1%) studies included the brain in the field of view. 150 PET/CT scans were performed in patients with diabetes, while 286 scans were in non-diabetic patients. Although there was no statistical difference, as expected the diabetic patients had higher average blood glucose of 137.8 ± 40.7 mg/dL compared to 98.9 ± 19.5 mg/dL.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Patients | 229 | |

| Total Studies | 436 | |

| Studies with Brian | 371 | 85.1% |

| Average # studies/pt (w/follow up). | 3.4 | |

| Male | 226 | 98.7% |

| Diabetes (DM) | 150/436 | 34.4% |

| Results based on # of studies | +/− SD | |

| Average Glucose (mg/dL) | 112.4 | 34.1 |

| Average Glucose −DM (mg/dL) | 98.9 | 19.5 |

| Average Glucose +DM (mg/dL) | 137.8 | 41.0 |

| Age (years) | 64 | 9.7 |

| BMI | 27.2 | 5.3 |

| BMI −DM | 26.0 | 5.0 |

| BMI +DM | 29.5 | 5.4 |

| Time Glucose to imaging (min) | 78.4 | 20.1 |

| Time FDG inj. to imaging (min) | 64.5 | 10.2 |

| Time Glucose to FDG inj. (min) | 13.7 | 17.6 |

| Dose MBq (mCi) | 466.2 (12.6) | 51.8 (1.4) |

| Tumor Type (studies) | N (studies) | % |

| Lymphoma | 111/436 | 25.5 |

| Lung cancer/Nodule evaluation | 156/436 | 35.8 |

| Oral SCCA | 60/436 | 13.8 |

| Other (Colon/Rectal/Pancreas/Melanoma) | 109/436 | 25.0 |

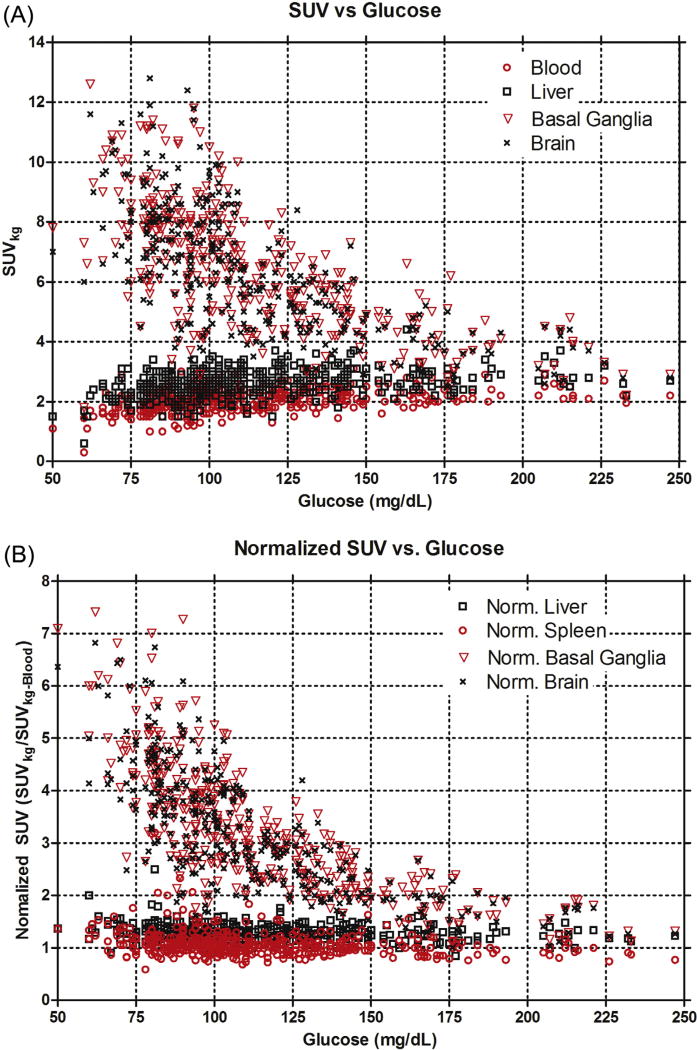

Average SUVkg measurements for selected target tissues: whole brain, basal ganglia, liver and blood-pool (spleen is omitted), are shown in Fig. 1. There is an inverse relationship between whole brain and basal ganglia SUVkg with glucose levels <130 mg/dL and progressively less dependence of SUVkg with increasing blood glucose levels > 130 mg/dL (Figs. 1–3). By contrast, mean SUVkg measurements of liver, spleen and blood-pool (spleen not shown) progressively increased with increasing blood glucose levels.

Fig. 1.

A) Standardized uptake value (SUVkg) as a function of plasma blood glucose at the time of FDG injection. There is decreased overall brain and basal ganglia FDG uptake with increased liver, blood-pool, and spleen (not shown) FDG uptake as a function of blood glucose levels. B) Standardized uptake value (SUVkg) normalized to the blood-pool SUVkg as a function of plasma blood glucose at the time of FDG injection. The data indicate a decreased overall normalized brain uptake and normalized basal ganglia uptake with increasing plasma blood glucose. However, unlike A, the normalized SUVkg values in the liver and spleen are not blood glucose dependent.

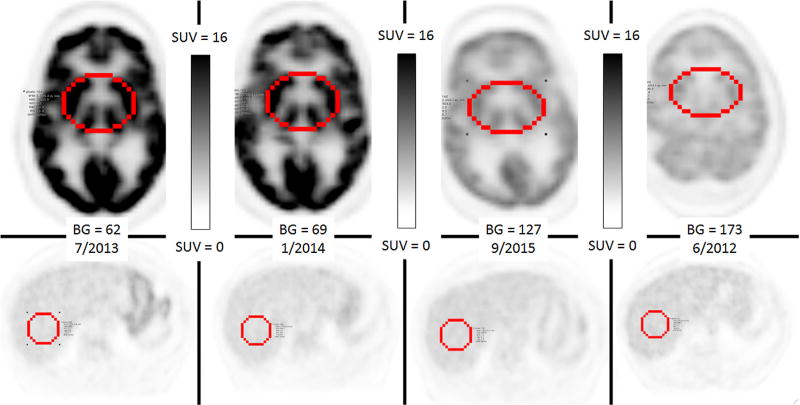

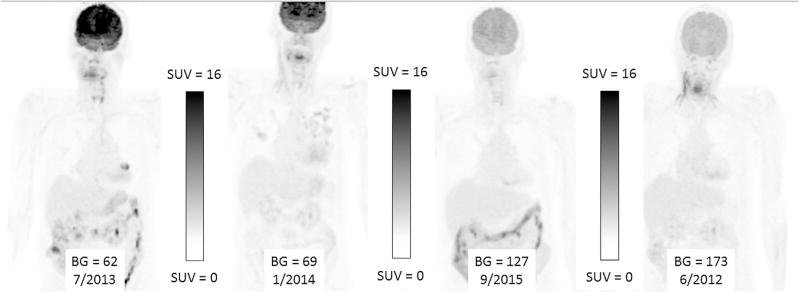

Fig. 3.

Axial images from the MIP images in Fig. 2 at that the level the ROI of the brain and liver were obtained. Similar to Fig. 2, each image is scaled identically between 0 and 16.0, with respect to Standardized uptake value (SUVkg). Again there is There is a significant decrease in brain FDG uptake associated with progressively increasing plasma glucose levels and subtle increased liver and blood-pool SUVkg.

Multivariate analysis for liver and blood-pool SUVkg FDG uptake were also related on blood glucose levels, but dependent on the BMI, presence or absence of diabetes and the tumor histology. Time from FDG injection to imaging (mean 64.5 ± 10.2 min) had no effect upon whole brain or other organ SUVkg measurements. Although demographic factors were related to changes in FDG uptake, interaction coefficient analysis did indicate that the effect of blood glucose on SUVkg was independent of other patient-specific variables. Overall variability of SUVkg dependence on blood glucose levels for different tissue types was least for blood-pool, followed by liver and spleen. Although the effect of blood glucose on FDG uptake was significant (p < 0.01) for both the blood and liver, their respective slopes (SUVkg/glucose) were not statistically different (p = 0.62). Conversely, spleen SUVkg, was influenced by the presence of diabetes. BMI, tumor type and blood glucose were not statically significant on SUVkg for spleen. Similar results for all tissues sampled were noted when SUV based on BMI was used (data not shown). The results of multivariate linear regression of SUVkg analysis for blood, liver, and spleen are shown in Table 2. Similar results were seen when SUVBMI was used with the exception that presence of diabetes was not a significant factor (data not shown). Univariate analysis of blood glucose effects on SUVkg and SUVBMI are shown in Table 3, demonstrating similar glucose effects as covariate adjusted analyses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of multivariable linear regression SUVkg average for blood-pool, liver, and spleen along with Ln(SUVkg) multivariable linear regression. Blood-pool measurements had the least degree of variability, as indicated by the lowest root mean square (MSE), while spleen had the highest degree of variability. Additionally, blood glucose effect (slope) was not different (p < 0.0001) between blood-pool and liver. The slope for blood glucose effect on the brain (ln transformed data) was larger and negative compared to that for the blood or liver. Note time from FDG injection to imaging time had no effect on the results.

| Estimate | Std Error | P value | Root MSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ln(Brain Ave. SUVkg) | ||||

| Intercept (Ln SUVkg) | 2.2363 | 0.1095 | < 0.0001 | |

| Glucose (Ln SUVkg/glucose) | −0.0067 | 0.0004 | < 0.0001 | |

| BMI | 0.0149 | 0.0025 | < 0.0001 | |

| Injections to Imaging Time | −0.0003 | 0.0013 | 0.8262 | |

| Diabetes (Ref = No) | −0.0739 | 0.0324 | 0.0232 | |

| Tumor Type (Ref = LUNG) | ||||

| LYMPH | −0.0727 | 0.0344 | 0.0356 | |

| OTHER | 0.0127 | 0.0334 | 0.703 | |

| SCCA | −0.0549 | 0.0386 | 0.1559 | |

| Blood Ave. SUVkg | 0.2991 | |||

| Intercept (SUVkg) | 1.1933 | 0.1299 | < 0.0001 | |

| Glucose (SUVkg/glucose) | 0.0044 | 0.0005 | < 0.0001 | |

| BMI | 0.0196 | 0.0031 | < 0.0001 | |

| Injections to Imaging Time | −0.0024 | 0.0015 | 0.1054 | |

| Diabetes (Ref = No) | −0.1655 | 0.0399 | < 0.0001 | |

| Tumor Type (Ref = LUNG) | ||||

| LYMPH | 0.0047 | 0.0406 | 0.9069 | |

| OTHER | 0.0942 | 0.0405 | 0.0206 | |

| SCCA | 0.0972 | 0.0476 | 0.0419 | |

| Liver Ave. SUVkg | 0.3688 | |||

| Intercept (SUVkg) | 1.2783 | 0.1602 | < 0.0001 | |

| Glucose (SUVkg/glucose) | 0.0047 | 0.0007 | < 0.0001 | |

| BMI | 0.0328 | 0.0039 | < 0.0001 | |

| Injections to Imaging Time | −0.0011 | 0.0018 | 0.5417 | |

| Diabetes (Ref = No) | −0.2345 | 0.0493 | < 0.0001 | |

| Tumor Type (Ref = LUNG) | ||||

| LYMPH | 0.0488 | 0.05 | 0.3304 | |

| OTHER | 0.1212 | 0.0499 | 0.0157 | |

| SCCA | 0.1501 | 0.0587 | 0.011 | |

| Spleen Ave. SUVkg | 0.3887 | |||

| Intercept (SUVkg) | 1.1509 | 0.1689 | < 0.0001 | |

| Glucose (SUVkg/glucose) | 0.001 | 0.0007 | 0.1553 | |

| BMI | 0.023 | 0.0041 | < 0.0001 | |

| Injections to Imaging Time | 0.0048 | 0.0019 | 0.0129 | |

| Diabetes (Ref = No) | −0.1268 | 0.0519 | 0.0151 | |

| Tumor Type (Ref = LUNG) | ||||

| LYMPH | 0.0779 | 0.0527 | 0.1405 | |

| OTHER | 0.0274 | 0.0526 | 0.6027 | |

| SCCA | −0.067 | 0.0619 | 0.2797 |

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of blood glucose versus SUV calculated by body weight in kg (SUVkg) Blood SUV demonstrates the least variability overall and spleen uptake is not affected by plasma blood glucose. Additionally, regardless of the method of SUV calculation, glucose has an effect on SUV. Additionally, the slope was not statistically different between the blood and liver either using SUVkg or SUVBMI (data not shown).

| Estimate | Std Error | P value | Root MSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Ave. SUVkg | 0.3284 | |||

| Intercept (SUVkg) | 1.5853 | 0.0551 | < 0.0001 | |

| Slope (SUVkg/glucose) | 0.0041 | 0.0005 | < 0.0001 | |

| Blood Ave. SUVBMI | 0.1166 | |||

| Intercept (SUVBMI) | 0.5105 | 0.0200 | < 0.0001 | |

| Slope (SUVBMI/glucose) | 0.0013 | 0.0002 | < 0.0001 | |

| Liver Ave. SUVkg | 0.4185 | |||

| Intercept (SUVkg) | 2.1191 | 0.0702 | < 0.0001 | |

| Slope (SUVkg/glucose) | 0.0043 | 0.0006 | < 0.0001 | |

| Liver Ave. SUVBMI | 0.1458 | |||

| Intercept (SUVBMI) | 0.6773 | 0.0250 | < 0.0001 | |

| Slope (SUVBMI/glucose) | 0.0014 | 0.0002 | < 0.0001 | |

| Spleen Ave. SUVkg | 0.4148 | |||

| Intercept (SUVkg) | 2.0322 | 0.0696 | < 0.0001 | |

| Slope (SUVkg/glucose) | 0.0011 | 0.0006 | 0.0515 | |

| Spleen Ave. SUVBMI | 0.1433 | |||

| Intercept (SUVBMI) | 0.6558 | 0.0246 | < 0.0001 | |

| Slope (SUV BMI/glucose) | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.1205 |

Analysis of uptake data normalized by blood SUVkg average demonstrated a trend of decreased normalized whole brain and basal ganglia FDG uptake as a function of blood glucose levels (Fig. 1b). However, there was no apparent effect of blood glucose levels on normalized SUVkg or SUVBMI measurements in liver and spleen (data not shown).

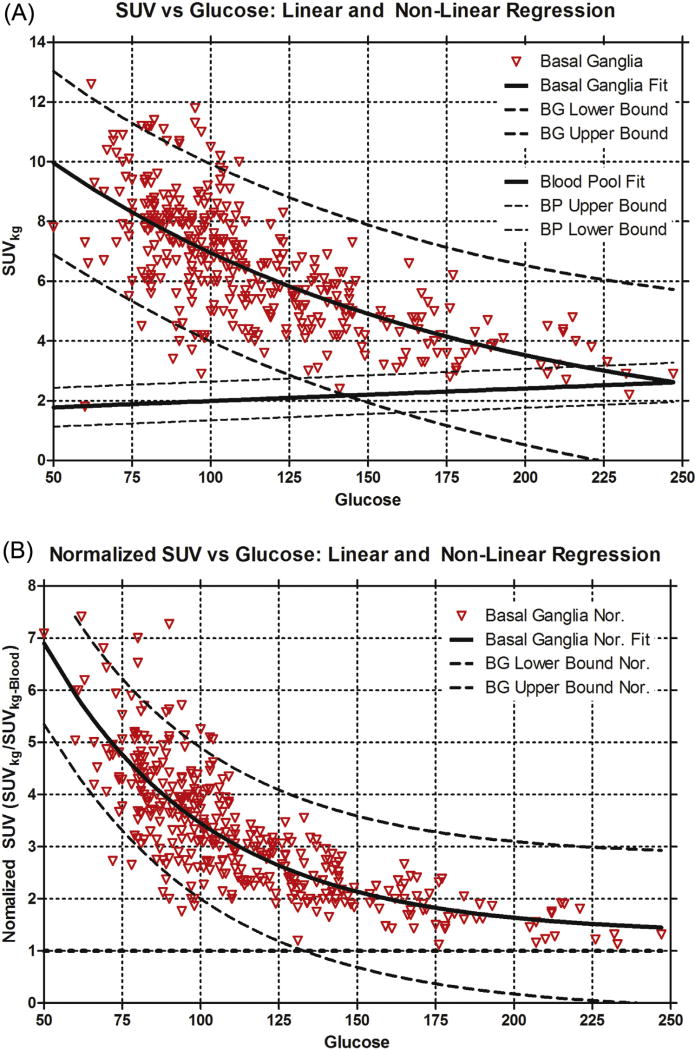

Non-linear regression using exponential decay was performed on the basal ganglia SUVkg and normalized basal ganglia SUVkg (Fig. 4a and b) with associated prediction bands. Multiple linear regression of logarithmic transform uptake data Ln(SUVkg) covariates are shown in Table 2. These results are similar in patient demographics that showed significant effects for liver and blood. However, the magnitude of blood glucose effect was increased and there was an inverse relationship with increasing blood glucose levels as shown in the raw data (Fig. 1).

Fig. 4.

A) Standardized uptake value (SUVkg) of the basal ganglia with associated nonlinear regression of the basal ganglia SUVkg and respective prediction bounds is shown. Linear regression and prediction bounds for the blood pool SUVkg is also provided. At a blood glucose of 125 mg/dL the prediction bounds overlap suggesting brain imaging should be performed when plasma glucose less than this. B) Normalized basal ganglia SUVkg with associated nonlinear regression of the normalized basal ganglia SUVkg and respective prediction bounds is shown. Again at glucose above 125 mg/dL the lower prediction band is at or below unity suggesting imaging of the brain should occur below this glucose level.

4. Discussion

Historically, interpretation of PET/CT for the evaluation of response of tumors to therapy and in distinguishing dementias has been based on qualitative assessment. More recently this interpretation has been enhanced with semi-quantitative imaging analysis. In tumor imaging the evaluation in response to therapy have used semi-quantitative assessment with incorporation of PERCIST criteria, proposed by Wahl et al. [11]. In brain, PET/CT diagnosis of dementia has been augmented by semi-quantitative assessment of the images using parametric voxel-based techniques as an adjunct to clinical diagnosis [1–3,12].

Similar to prior reports, we found that cerebral cortical FDG uptake has a negative inverse relationship to plasma blood glucose levels; with decreasing brain SUV as blood glucose levels increase [4,5]. Our inclusion of oncology patients rather than normal subjects allowed us to consider plasma blood glucose levels as a continual variable resulting in linear regression modeling rather than categorical comparisons. Both absolute and normalized whole brain FDG uptake declined by almost 50% from a blood glucose of ~60 mg/dL to level around 150 mg/dL and then more gradually greater than 150 mg/dL. Overall, this decrease of uptake is expected based on competitive inhibition of glucose to FDG. However, the nonlinear response suggests a more complicated mechanisms then simple single site competitive inhibition of FDG uptake.

Much of the research to understand cerebral metabolism occurred with C-11/C-14-labelled glucose and FDG and was pursued in the 80’s and 90’s. The established assumption for that research occurred in the 1960ies, were the cerebral glucose metabolic rate had been shown to be fixed and unaffected by mental activity, diet, fasting state etc. (no presence of specific mental disorders, drugs, etc.) [13]. In a review by Louis Sokoloff [14] the mechanism of labeled glucose uptake is based on transport through the Glut family of cellular receptors and glucose phosphorylation by hexokinase. Based, on C-14 labeled glucose it was shown that glucose and FDG do not have identical rate constants for GLUT receptor transport or hexokinase phosphorylation. The correction factor of rate constants for FDG compared to glucose termed the “isotope effect” by Sokoloff [14] is now referred to as the “lumped constant”. The so-called lumped constant was assumed to be independent of blood glucose levels (in the range where most clinical imaging is done), lending a constraining of glucose transport.

However, our data suggest that the lumped constant is not uniform over the physiological range under which imaging generally occurs given given the nonlinear (and/or dual linear) relationship of plasma glucose to whole brain SUV. This observation is also supported by recent animal studies demonstrating that in rats plasma blood glucose levels affect the calculated lumped constant [15–18] such that brain SUV represents a Glut transporter limited process for FDG in the hypoglycemic-to-euglycemia range, then switched to an intracellular hexokinase phosphorylation-limited process in the hyperglycemic state [15].

Our data showed that doubling of plasma blood glucose from 60 mg/dL to 120 mg/dL results in a ~50% drop in uptake (absolute or normalized; Figs. 1 and 3) due to Glut limited transport mechanism. Consequently, this suggests a possible correction to an improved image quality in patients within in the upper range of normal-glycaemia to mild hypoglycemia is to increase the image acquisition time proportionally improving the counting statistics for the image. However, above a plasma blood glucose of ~150 mg/dl changes in SUV are less sensitive to changes in blood glucose (given the different mechanism). Therefore, one may want to avoid imaging the brain given the profound decreased uptake comparted to the hypoglycemic-to-euglycemia patient both from a qualitative point of view, and that the semi-quantitative techniques rely on a normal data base of patients that were imaged at a lower blood glucose.

Conversely, our findings in the liver demonstrate a positive correlation between blood glucose levels and liver FDG uptake, an observation that has been confirmed by others. In 228 patients presenting for oncology staging with low (<100 mg/dL), middle (100–160 mg/dL) and high blood glucose levels (>160 mg/dL) a similar, linear relationship, was found between hepatic uptake and blood glucose levels [19]. In 70 non-diabetic patients imaged with FDG PET/CT at 60 min and 68 nondiabetic patients imaged at 90 min, higher glucose levels were associated with higher hepatic FDG uptake, particularly at the delayed (90 min) imaging time-point [20]. These effects were observed at glucose levels with a threshold of <125 mg/dL, a level that considered satisfactory for clinical PET imaging. Therefore glucose uptake in the liver is neither glucose saturable nor dependent on Glut-2 for glucose and FDG transport [21].

Wahl et al. [11] concluded that evaluation for metabolic response in a target lesion should only occur if the liver (as the internal reference tissue is absent of disease) has <20% difference in SUV measurements and or an absolute difference < 0.3 SUV between the two studies. SUV is also based on lean body mass. Additionally, Wahl et al. suggests the studies should be performed at 60 min after FDG injection (no less than 50), on the same imaging device using the same imaging protocol. All of our imaging adhered to these requirements and ROI were obtained for the liver and blood pool (the recommended reference source if liver disease was present). SUV was calculated based on weight (kg, and standard output of the Siemens Biograph) and BMI. The later was used as a correlate to SUV based on lean body mass, as it accounts for height variation [22–24].

In our study we demonstrate that liver and blood pool SUV measurements are dependent on plasma blood glucose and patient specific factors. Further, we show that, the ‘glucose effect’ is decreased when SUV is calculated by BMI rather than body weight, supporting PERCIST recommendations. However, contrary to PERCIST recommendations, our data suggest that blood pool would be a more optimal reference tissue given decreased variability with smaller standard errors on the multi-linear regression with respect to plasma glucose levels regardless of which method of SUV calculation is performed. Irrespective in the method of calculation chosen, the “glucose effect” on the liver or blood is not statistically different. Our data also suggest that the important issue is that the choice of reference tissue remains constant from study to study for a given patient.

There are several limitations of our study, it is retrospective lending to performing global brain uptake analysis (rather than a segmentation analysis), is overwhelmingly a male predominate cohort with a single institution’s oncology referral surrogate for normal brain subjects, with data derived from a single vendor PET SUV analysis algorithm. Additionally, the timing that measurements were made were optimized for tumor imaging rather than brain imaging as has been suggested by several societies [6–8,11]. Despite these obvious limitations our observations will likely apply to a larger and more diverse patient populations. Specifically, to the timing of FDG injection to SUV measurements, ideally this would occur at 30 min rather than the planed 60 min. This later time is chosen to allowing clearance of FDG from non target tissue. Contrary, in neuro imaging 30 min is chosen to increase gray mater activity since there is no significant non target tissue around to wait for clearance. Moreover, while the blood-pool SUV exhibited the least variability as a reference tissue compared to liver or spleen, the effect of glucose levels although significant, was quantitatively small. Our data confirm that normalizing brain uptake to an internal reference tissue, blood, decreases variability of brain FDG uptake for a given plasma blood glucose level.

Future analyses of these findings, specifically looking at segmentation analysis in the brain, would confirm a benefit for blood glucose correction to target organs/tissues in neurologic imaging. While in tumor imaging, the choice of liver as a reference could be improved by using blood pool given the reduced variability that blood glucose and patient specific factors have. These corrections could potentially improve semi quantitative PET/CT image analyses in neurologic and oncologic imaging.

5. Conclusion

Effect of hyperglycemia on brain and liver FDG uptake and SUV measurements has implications for quantitative PET analysis that requires robust measurement methods across a broad range of patient specific conditions.

Fig. 2.

Maximal Intensity Pixel (MIP) PET images of a patient imaged on 4 separate occasions for a lung nodule. Each image is scaled identically between 0 and 16.0, with respect to Standardized uptake value (SUVkg). There is a significant decrease in brain FDG uptake associated with progressively increasing plasma glucose levels and subtle increased liver and blood-pool SUVkg.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Ann Arbor VA medical facility and the contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Shivamurthy VK, Tahari AK, Marcus C, Subramaniam RM. Brain FDG PET and the diagnosis of dementia. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015;204(1):W76–W85. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallucci M, Limbucci N, Catalucci A, Caulo M. Neurodegenerative diseases. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 2008;46:799–817. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2008.06.002. (vii.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman RE. Positron emission tomography diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2005;15:837–846. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keramida G, Dizdarevic S, Bush J, Peters AM. Quantification of tumour (18) F-FDG uptake: normalise to blood glucose or scale to liver uptake? Eur. Radiol. 2015;25:2701–2708. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3659-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claeys J, Mertens K, D’Asseler Y, Goethals I. Normoglycemic plasma glucose levels affect F-18 FDG uptake in the brain. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2010;24(6):501–505. doi: 10.1007/s12149-010-0359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varrone A, Asenbaum S, Vander Borght T, et al. EANM procedure guidelines for PET brain imaging using [18F]FDG, version 2. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2009;36:2103–2110. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boellaard R, O’Doherty MJ, Weber WA, et al. FDG PET and PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour PET imaging: version 1.0. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2010;37:181–200. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1297-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boellaard R, Delgado-Bolton R, Oyen WJ, et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: version 2.0. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2015;42:328–354. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2961-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawasaki K, Ishii K, Saito Y, Oda K, Kimura Y, Ishiwata K. Influence of mild hyperglycemia on cerebral FDG distribution patterns calculated by statistical parametric mapping. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2008;22:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s12149-007-0099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishibashi K, Kawasaki K, Ishiwata K, Ishii K. Reduced uptake of 18F-FDG and 15O-H2O in Alzheimer’s disease-related regions after glucose loading. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:1380–1385. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA. From RECIST to PERCIST: evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;50(Suppl. 1):122S–150S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Heertum RL, Tikofsky RS. Positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography brain imaging in the evaluation of dementia. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2003;33:77–s85. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2003.127294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Socoloff L. The metabolism of the central nervous system in vivo. Vol. 3. American Physiological Society; Washington, DC: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sokoloff L. Localization of functional activity in the central nervous system by measurement of glucose utilization with radioactive deoxyglucose. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1981;1:7–36. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1981.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crane PD, Pardridge WM, Braun LD, Oldendorf WH. Kinetics of transport and phosphorylation of 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1983;40:160–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb12666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori K, Cruz N, Dienel G, Nelson T, Sokoloff L. Direct chemical measurement of the lambda of the lumped constant of the [14C]deoxyglucose method in rat brain: effects of arterial plasma glucose level on the distribution spaces of [14C]deoxyglucose and glucose and on lambda. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:304–314. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuier F, Orzi F, Suda S, Lucignani G, Kennedy C, Sokoloff L. Influence of plasma glucose concentration on lumped constant of the deoxyglucose method: effects of hyperglycemia in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:765–773. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suda S, Shinohara M, Miyaoka M, Lucignani G, Kennedy C, Sokoloff L. The lumped constant of the deoxyglucose method in hypoglycemia: effects of moderate hypoglycemia on local cerebral glucose utilization in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:499–509. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webb RL, Landau E, Klein D, et al. Effects of varying serum glucose levels on 18F-FDG biodistribution. sNucl. Med. Commun. 2015;36:717–721. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubota K, Watanabe H, Murata Y, et al. Effects of blood glucose level on FDG uptake by liver: a FDG-PET/CT study. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2011;38:347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy FN, Beaulieu S, Boucher L, Bourdeau I, Cohade C. Impact of intravenous insulin on 18F-FDG PET in diabetic cancer patients. J. Nucl. Med. 50. 2009:178–183. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Absalom AR, Mani V, De Smet T, Struys MM. Pharmacokinetic models for propofol–defining and illuminating the devil in the detail. Br. J. Anaesth. 2009;103:26–37. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boer P. Estimated lean body mass as an index for normalization of body fluid volumes in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1984;247:F632–636. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1984.247.4.F632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters AM, Snelling HL, Glass DM, Bird NJ. Estimation of lean body mass in children. Br. J. Anaesth. 2011;106:719–s723. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]