Abstract

Transplantations of various stem cells or their progeny have repeatedly improved cardiac performance in animal models of myocardial injury, however, the benefits observed in clinical trials have been generally less consistent. Some of the recognized challenges are poor engraftment of implanted cells and, in the case of human cardiomyocytes, functional immaturity and lack of electrical integration, leading to limited contribution to the heart’s contractile activity and increased arrhythmogenic risks. Advances in tissue and genetic engineering techniques are expected to improve the survival and integration of transplanted cells, and to support structural, functional, and bioenergetic recovery of the recipient hearts. Specifically, application of a prefabricated cardiac tissue patch to prevent dilation and to improve pumping efficiency of the infarcted heart offers a promising strategy for making stem cell therapy a clinical reality.

Keywords: biocompatible materials, heart failure, myocardial infarction, myocardium, stem cells

Introduction

Although transplanted cells and engineered tissues result in improved cardiac performance when tested in animal models of myocardial injury, the benefits observed in clinical trials have generally been modest at best. Opinions regarding the optimal cell type or combination of cell types have yet to reach consensus, and only a very small proportion of the administered cells are engrafted by the native myocardium. Cellular attrition is often attributed to a lack of perfusion in the infarcted region, but the recipient’s immune system may also play a role, particularly in preclinical studies with human-derived tissues or other xenogeneic transplantation experiments. Furthermore, the surviving cells rarely produce grafts of substantial size and may remain electrically isolated from the native myocardium, which would prevent the graft from contributing to the contractile activity of the heart and, more importantly, could lead to arrhythmogenic complications, which may be the primary safety concern associated with transplanted myocardial cells and tissues. Tissue engineering strategies are expected to improve engraftment of transplanted cells, as well as structural, functional, and bioenergetic recovery of the infarcted heart. These and many other topics were discussed by attendees of the National Institutes of Health 2016 Progenitor Cell Biology Consortium and Cardiovascular Tissue Engineering Symposium at the University of Alabama, Birmingham on March 28, 2016. Here, we present some of the more provocative ideas and advances that were discussed at the meeting and that may facilitate the translation of cardiac cell- and tissue-engineering therapies from the laboratory to the clinic.

Cell Types for Use in Cardiac Therapy

A wide variety of cell sources have been evaluated for repair of the ischemic myocardium in animal models, and a subset of these have undergone testing in clinical trials. A recent review by Nguyen et al. (1) summarized the clinical trials on stem cell therapy for ischemic heart diseases and heart failure from January 1, 2000 to July 2016. Table 1 adds the new clinical trials for ischemic heart diseases and heart failure published between July 27, 2016 and May 18, 2017, based on our PubMed search results, as well as clinical trials for stem cell therapy for congenital heart diseases.

Table 1.

Published Stem/Progenitor Cell Clinical Trials for Heart Diseases

| Diseases | Trial Design | Sample Size | Cell Type | Cell Source | Delivery Route | Follow-Up | Summary/Observation | Trial Name/Identifier | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Function | Others | ||||||||

| HLHS | Nonrandomized (phase 1) | 7 | Autologous CDC | Cardiosphere | IC | 18–36 months | ↑ RVEF | Improved somatic growth | TICAP/NCT01273857 (76,77) |

|

| |||||||||

| HLHS | Randomized (phase 2) | 34 | Autologous CDC | Cardiosphere | IC | 12 months | ↑ RVEF | Reduced fibrosis, improved somatic growth | PERSEUS/NCT01829750 (78) |

|

| |||||||||

| Ischemic heart disease | Randomized control (phase 2) | 90 | Autologous BMCs | Bone marrow | IC vs. IM | 6–12 months | ↑ LVEF in IM group but not in IC group | ↓ NT-proBNP in IM group but not IC group | REGENERATE-IHD/NCT00747708 (79) |

|

| |||||||||

| Ischemic heart disease | Randomized control (phase 3) | 271 | Autologous MSCs | Bone marrow | IM | 39 weeks | No change LVEF | ↓ incidence of sudden or aborted sudden deaths | CHART-1/NCT01768702 (80) |

|

| |||||||||

| Nonischemic cardiomyopathy | Randomized control (phase 2) | 22 | Allogeneic MSCs | Bone marrow | IV | 90 days | No change LVEF | ↑ health status and ↓ circulating inflammatory cells | NCT02467387 (81) |

|

| |||||||||

| Refractory Angina | Randomized control (phase 2) | 31 | Autologous CD133+ cells | Bone marrow | TEP | 1, 4, 6, and 12 months | No change LVEF | ↓ angina | REGENT-VSEL/NCT01660581 (82) |

|

| |||||||||

| Ischemic vs. nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy | Nonrandomized (phase 1) | 27 | Autologous skeletal stem-cell sheets | Skeletal muscle (vastus medialis) | Sutured to heart surface | 12 months | ↑ LVEF in patients with ischemic heart diseases, but not in patients with nonischemic heart diseases | ↓ BNP in patients with ischemic heart diseases, but not in patients with nonischemic heart diseases | UMIN000003273 (83) |

|

| |||||||||

| Nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy | Randomized (phase 2) | 37 | Allogeneic MSC (19 patients) vs. autologous MSC (18 patients) | Bone marrow | TEP | 12 months | ↑ LVEF in allo-MSC group, but not in the auto-MSC group | ↓ TNF-α, to a greater extent with allo-hMSCs versus auto-hMSCs at 6 months | POSEIDON-DCM/NCT01392625 (24) |

|

| |||||||||

| STEMI | Randomized control (phase 2) | 188 | Autologous BMCs | Bone marrow | IC | 6 months | ↑ LVEF in BMC group | No treatment effect in irradiated BMC group | BOOST-2/ISRCTN17457407 (84) |

BMC = bone marrow–derived cell; BNP = B-type natriuretic peptide; CDC = cardiosphere-derived cells; HLHS = hypoplastic left heart syndrome; hMSC = human mesenchymal stem cell; IC = intracoronary infusion; IM: = intramyocardial injection; IV = intravenous; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MSC = mesenchymal stem cell; NT-proBNP = N=-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; RVEF = right ventricular ejection fraction; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TEP = transendocardial injection; TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) and newer cell types, such as induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) (2,3), are especially promising for cardiac cell and tissue engineering therapy (4–6) because they can be efficiently differentiated into functional cardiomyocytes (CMs), endothelial cells (ECs), and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) (7–11). However, the optimal proportions of each cell type have yet to be identified, and a variety of other cell lineages (e.g., resident cardiac progenitor cells [CPCs]) (12) may be needed to maximize therapeutic effectiveness. Furthermore, mitochondria have important functions in cardiac metabolism (13) and programmed cardiomyocyte death (14), and emerging roles in cardiac differentiation were recently suggested (15,16). Specifically, CM differentiation requires the membranes of adjacent mitochondria to fuse, and fusion of the outer membranes is regulated by mitofusins 1 and 2, which direct ESC differentiation into cardiomyocytes via regulation of calcineurin and Notch signaling (16).

The importance of restoring functional cardiomyocytes for post-infarction repair is self-evident because they provide the mechanical force needed for contraction. In a rat model of myocardial infarction (MI), measurements of cardiac function and remodeling were significantly better when implanted fibrin gel-based tissue-engineered patches were created from the complete population of neonatal rat cardiac cells than when the cardiomyocytes were omitted (17). Furthermore, extracellular matrix production in tissue-engineered patches appears to increase in response to production of transforming growth factor β1 by cardiomyocytes (18,19), and cardiomyocytes are an important source of vascular endothelial growth factor in cell sheet–based engineered tissues (20). Thus, cardiomyocytes and cytokines that mediate CM–non-CM communication are crucial components of the beneficial activity induced by transplanted engineered cardiac tissues.

Other cell sources of potential utility for cardiac repair include mesenchymal stem cells (prototypically derived from bone barrow), cardiac stem cells, cardiospheres isolated from endocardial biopsies (in mice and humans), which are composed of a heterogeneous cell population, but are exceptionally proliferative, and Abcg2-expressing progenitor cells (21). When suspended in saline and transplanted into the hearts of mice after an acute infarction, Sca-1+/CD31− cells appear to attenuate decline in cardiac function, increase myocardial neovascularization, and modestly promote cardiomyocyte differentiation from graft cells, as well as host cell proliferation (22).

Variation of interspecies responses to cell therapy is another critical issue. Commonly used preclinical models include nonhuman primates, large mammals (swine, dog, and others), and rodents. Although it might be necessary, there is neither guidance on selection of preclinical animal models nor consensus criteria on experimental design for preclinical studies thus far. Genetic background may affect the interpretation of experimental results. Therefore, comparison and validation of data collected from different species is important when translating preclinical research to clinical trials.

Although transplantation of various cell types has been reported to improve left ventricular (LV) function and structure after MI, overwhelming evidence has demonstrated that there is no significant long-term engraftment of adoptively transferred cells into the host myocardium. The persistence of beneficial effects, despite the disappearance of transplanted cells, indicates that cell therapy may act via paracrine mechanisms. In addition, the rapid clearance of cells from the host myocardium suggests that the benefits of cell therapy are limited by the poor engraftment of the cells, implying that 1 dose does not adequately test the efficacy of that cell product (23). However, almost all preclinical and clinical studies of cell therapy performed heretofore have based their assessment of efficacy on the outcome of 1 administration of a cell product. The problem of modest or no beneficial effects might be overcome by repeated cell doses. The rationale is that just as most pharmacological agents are ineffective when given once, but can be highly effective when given repeatedly, a cell product might be ineffective or modestly effective as a single treatment, but might be quite efficacious if given repeatedly.

On the basis of preclinical data performed in large animal models, human testing of various adult cell sources has progressed from phase I to phase III trials (24,25). From a mechanistic standpoint, cell therapy in the iterations described earlier reduces tissue fibrosis, restores tissue perfusion, has a powerful anti-inflammatory effect, and stimulates myogenesis, largely by promoting endogenous myogenesis (24). Moreover, clinical trial activity is extending into numerous cardiomyopathic disease states, including hypoplastic left heart syndrome, adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy, and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Future efforts to apply tissue-engineering strategies in the clinical setting will emerge following appropriate preclinical testing.

Cell Engraftment

As many as 1 billion cardiomyocytes are lost during MI, and although the typical dose of transplanted cells may approach or exceed this number, just 0.1% to 10% of the cells are engrafted into the myocardium and continue to survive for more than a few weeks after transplantation (26,27). Much of this attrition can be attributed to the harsh environment in and near the region of the infarct; thus, one strategy for improving engraftment and survival of transplanted cells is to use natural or artificial biomaterials that provide a protective environment for the transplanted cells (28–30). Overall, published reports indicate that the functional benefits of the cardiac cell patch therapy critically depend upon the longer-term structural integrity of the cell patches. Maintenance of longer-term graft size remains a major challenge in preclinical trials of cell therapy.

Immunogenicity

One of the chief benefits of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) is that they can be generated from a patient’s own somatic cells, and consequently are not expected to provoke an immune response after transplantation. Although this approach holds appeal for avoiding pharmacological immunosuppression and associated complications, it requires a substantial time window (months) for hiPSC generation, followed by differentiation and graft formation. Thus, this autologous approach is better suited to treatment of more chronic heart failure with existing technology. However, some studies suggest that the immune tolerance of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)–derived cells may vary depending on the cells’ lineage (31–34). Questions regarding immunogenicity are often addressed by performing experiments in mice with humanized immune systems, but the currently available models have a limited lifespan and inconsistent immune response, perhaps because the animals’ endogenous immune system is eliminated with sublethal doses of radiation. Collectively, these observations suggest that translation of hiPSC-derived cell technology to clinical applications will likely require testing of the immunogenicity of each hiPSC-derived cell lineage in a new generation of models that can provide more consistent and reliable results.

Allograft rejection is primarily mediated by host-derived reactive T lymphocytes that recognize nonself human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) on the surface of transplanted donor cells. Humans have 2 main categories of HLAs: major histocompatibility complex (MHC) classes I and II. The Townes laboratory recently showed that surface expression of HLA class I molecules can be largely eliminated in a line of human embryonic stem cells (H9) using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) gene-editing system to knock out both alleles of the gene for β2 microglobulin, which is essential for cell-surface expression of HLA class I and stability of the peptide-binding groove. CRISPR/Cas gene editing has also been used to knock out the Class II MHC transactivator (CIITA) in human ECs, and the CIITA-knockout ECs could be transplanted into mice without producing an immune response (35). The degree of differentiation of the hiPSCs derivatives engrafted may also influence the immunogenicity of the tissue grafts. This is particularly relevant for tissue-engineering applications, because even when professional antigen-presenting cells are depleted, cell-mediated allograft rejection can still occur (36). This is perhaps because human ECs activate alloantigen-reactive memory CD4+ T cells via a mechanism requiring expression of class II MHCs. Thus, gene-editing technologies may enable researchers to create “universal donor” hiPSC lines, as well as hiPSC-derived cells and engineered tissues with substantially higher rates of engraftment that can be used to treat a wider variety of patients and diseases.

Immunomodulation

As described earlier, stem cell engraftment rates and survival following transplantation are disappointingly low. Moreover, among surviving transplanted progenitor cells, the demonstrable magnitude of differentiation into functional cardiomyocytes has been variable, ranging from no evidence of cardiomyocyte differentiation to generation of small, apparently integrated cardiomyocytes (22,26,37–39). Most studies of cell therapy seek to intervene therapeutically either after MI or during chronic heart failure. The proinflammatory environment of the failing heart may also be responsible for the reported functional benefits of cardiac cell therapies. As both of these pathological scenarios exhibit heightened inflammatory activation and innate and adaptive immune cell infiltration in the myocardium (40–43), these microenvironmental factors may be important contributors to the suboptimal responses to cell therapy. For example, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a proinflammatory cytokine elaborated by both immune cells and failing cardiomyocytes, restrains cardiomyocyte differentiation of resident cardiac stem cells, and can channel an alternate neuroadrenergic-like fate in vitro (44); these effects would be expected to diminish the reparative effects of stem cell therapy. Such findings suggest that immunomodulation of the proinflammatory microenvironment in recipients of progenitor cell therapy may be a high-yield strategy to enhance cell engraftment and cardiomyocyte differentiation. To date, such approaches have been relatively unexplored, but could include targeting specific innate immune cell populations (e.g., infiltrating and proinflammatory macrophages), specific cytokines (e.g., TNF), and/or antigen-independent T-cell responses. These methodologies would be complementary to the suppression of antigen-dependent MHC responses described earlier, and would ideally comprise circumscribed interventions designed to improve cell engraftment at the time of delivery and subsequent cardiomyocyte differentiation during initial repair. Interestingly, mesenchymal stem cells suppress TNF levels substantially, and this effect may therefore contribute to some of the positive effects of these cells in clinical trials (24).

Arrhythmogenesis

Injected hPSC–derived cardiomyocytes have not been associated with arrhythmias in rodents, but when the dose was scaled up for delivery to nonhuman primates (macaques), all 4 of the cell-treated animals experienced periods of premature ventricular contractions and/or ventricular tachycardia (30). These results were recently confirmed in a larger set of macaques upon allogeneic transplantation of macaque pluripotent stem cell (PSC)–derived cardiomyocytes suspended in prosurvival cocktail (45). The discrepancy between observations in rodents and macaques may have occurred because the large dose of cells administered to macaques was accompanied by a dramatic (≥10-fold) increase in tissue graft size. As the action potential passes through the myocardium, the anatomic and/or functional heterogeneity introduced by these large regions of immature, electrically-active tissue may slow down or partially block conduction, thus setting the conditions for life-threatening re-entrant arrhythmias (46). As they are electrically immature and contain sinoatrial nodal cells, hPSC-cardiomyocytes possess autonomous pacemaking activity and, consequently, are capable of ectopic beats that could further precipitate arrhythmia induction. If exogenous cells indeed engraft at much higher rate, this may result in even more severe ventricular arrhythmias. Of note, compared with human hearts, macaque hearts are much smaller and their resting rate is much higher, which raises doubts as to their suitability for predicting arrhythmogenic risks in humans. Although larger animals, such as pigs, are a better model of human heart physiology, objective assessment of human cell therapies in large animals will require adequate immunosuppression, which may be easiest to achieve in nonhuman primates.

In adult mammalian hearts, electrical propagation and myocardial contractions are coordinated primarily through the gap-junction proteins connexin 40, connexin 43 (Cx43), and connexin 45 (47), of which Cx43 is by far the most abundant. Cx43 is expressed in both atrial and ventricular myocytes (48), and deficiencies in Cx43 expression or organization have been linked to development of arrhythmias in patients with heart failure and other cardiomyopathies (47,49,50). Furthermore, previous studies (51) suggested that the risk of arrhythmogenic complications from transplanted cells may decline substantially if the cells were genetically modified to overexpress Cx43. Thus, graft-associated arrhythmogenicity may be substantially reduced by using gene-editing technologies to increase expression of gap-junction proteins in transplanted cardiomyocytes or surrounding nonmyocytes. Still, the small cell size and immature expression and distribution of ion channels and gap junctions in transplanted cardiomyocytes, as well as the isotropic architecture of the grafts, likely contributed to the occurrence of arrhythmias in macaques, despite proven host-graft Cx43 coupling (30,45). Additional experimental and computational studies are warranted to establish critical structural and functional properties of transplanted grafts leading to increased arrhythmia susceptibility.

Furthermore, the results from a recent study (52) suggest that intramyocardially-injected cardiac microtissue particles (consisting of ~1,000 cells/particle) suspended in prosurvival cocktail produce grafts that are electrically coupled to the native myocardium, but an epicardially-implanted engineered cardiac tissue patch does not. The combined use of genetically-encoded fluorescent calcium reporters (e.g., GCaMP) (45,53) targeted to transplanted cells and voltage-sensitive dyes with nonoverlapping emission spectra labeling host myocardial tissue will be valuable for exploring the mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis and evaluating the effectiveness of strategies for improving electromechanical integration of engineered myocardial grafts.

Myocardial Bioenergetics

The contractile activity of engineered myocardial tissue is expected to contribute directly to myocardial performance, but improvements can also evolve through the release of cytokines that promote angiogenesis, activate endogenous progenitor cells (20,54), or stimulate other beneficial paracrine pathways. Furthermore, the damage induced by an acute infarct event is exacerbated by chronic myocardial overload, dilation, and overstretching, which increases wall stress and can lead to metabolic abnormalities, such as declines in the rate of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) use or in the ratio of phosphocreatine to ATP in surrounding cardiomyocytes (55–58). These bioenergetic abnormalities were largely corrected when hiPSCs were differentiated into hiPSC-ECs and hiPSC-SMCs, and then suspended in a fibrin scaffold positioned over the site of infarction in swine hearts (55). Thus, a considerable amount of the benefit associated with engineered tissue transplantation may stem from the structural support of the graft or its cytokine production, in addition to direct remuscularization of the injured region.

Engineered Organs

Current limitations of human organ transplants have prompted researchers to consider use of xenogeneic organs as an alternative strategy. For example, functional pancreatata composed of rat cells have been generated in mice by injecting murine blastocysts with rat pluripotent stem cells (59), and then transplanting the blastocysts into surrogate mouse dams. Importantly, the blastocysts could not generate the target organ because they expressed a mutated form of Pdx1, the master regulatory gene for pancreatic development, and consequently provided a niche for the development of the wild-type rat organ. This “blastocyst complementation” strategy has also been used to produce livers and kidneys in rodents and pancreatata in pigs (60–62), whereas members of the Garry laboratory used an analogous approach that combined gene editing with somatic cell nuclear transfer to engineer pig embryos that lacked cardiovascular cells, and then rescued this deficiency with wild-type, green fluorescent protein–labeled pig blastomeres. Although these studies support the feasibility of generating patient-specific organs that can be used as models for preclinical work or, perhaps, as organs for transplantation therapy, the utility of this technology will remain limited until methods for generating organs from human stem cells become more efficient.

Stimulating Endogenous Regeneration and Repair

In addition to transplantation of exogenous stem cells and engineered tissues or organs, the ability to stimulate endogenous cardiac repair could eventually lead to development of effective cell-free therapies for MI. Lower organisms, such as the newt and zebrafish, as well as neonatal mice, have a tremendous ability to regenerate from severe myocardial injury (22), but the regenerative capacity of adult mouse and human hearts is much more limited. Nevertheless, studies that map cell fate or use radiocarbon dating indicate that both murine and human cardiomyocytes are continually replaced, albeit at a very low rate: an average of ~1% of human cardiomyocytes are newly formed each year, with roughly one-half of the cells replaced over a lifetime (59). A number of studies indicate that adult hearts can be remuscularized through the proliferation and differentiation of c-kit+ CPCs, and endogenous CPCs may also release exosomes or paracrine factors that modulate the repair process and promote neovascularization. Nevertheless, genetic fate-mapping assessments by van Berlo et al. (63,64) indicated that although c-kit+ CPCs can give rise to cardiomyocytes, they do so in an extremely limited fashion. Newly emerging studies are showing that endogenous repair mechanisms can be dramatically up-regulated (65).

Furthermore, although the fibroproliferative response (i.e., scar formation) is beneficial for short-term stability at the injury site, it interferes with subsequent repair processes, such as vascular growth and potentially remuscularization. Thus, researchers have also begun to investigate methods for controlling or reverting fibrosis by reprogramming fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes or ECs (66–68), and by identifying the cellular source(s) contributing to scar formation (69,70). The use of tissue-engineered systems may increase in vitro efficacy and improve understanding of the direct cardiac reprogramming processes (71,72), as well as permit well-controlled mechanistic studies of cardiomyocyte/nonmyocyte interactions (73).

Disparity between Preclinical and Clinical Study Results

The positive results from studies of cell therapy for the treatment of MI in small-animal models have generally not been observed in clinical trials. For example, results from a phase I clinical trial indicated that although intracoronary administration of autologous cardiac sphere-derived stem cells associated with a significantly decreased infarction size in patients with acute MI, LV chamber function did not improve (74). Many of the factors that determine the effectiveness of cell- or engineered-tissue–based therapies likely depend both on the unique characteristics of each specific disease state and on complex interactions among numerous mechanisms of action, but these variables cannot be adequately or safely explored in clinical investigations. Future tissue-engineering therapies for MI are expected to face the same logistic issues. Thus, relevant large-animal models of myocardial dysfunction are critical for identifying, characterizing, and quantifying the physiological response to cell and tissue transplantation therapies, as well as the optimal cell or biomaterial type, dose, timing, and route of administration, to ensure that each patient receives the maximum possible benefit while avoiding the complications associated with overtreatment.

Conclusions

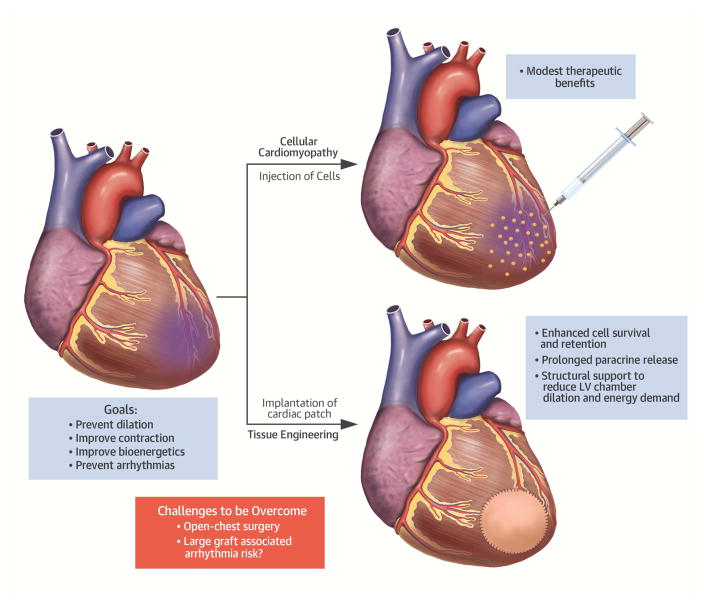

Although adult bone marrow- or myocardium-derived progenitors can offer multiple paracrine benefits to surviving cardiomyocytes in the infarcted heart, they are unlikely to contribute to the formation of de novo working myocardium (75). Cardiomyocytes derived from pluripotent stem cells can address this challenge, but are more complicated to use in autologous therapies and potentially less robust to surviving transplantation. Although the jury for the optimal cell source is still out, it is possible that different disease applications will require different cell types, and that a mixture of immune-matched or immune-engineered PSC-derived cardiomyocytes and host-derived stromal progenitors will prove optimal in inducing heart remuscularization, while supporting cell survival and engraftment. Notably, applications of pre-formed engineered cardiac tissue patches with specifically tailored cell compositions could significantly increase both the survival and the beneficial effects of transplanted cells. Furthermore, because paracrine factors, including extracellular vesicles, are responsible for much of the observed beneficial effects of cardiac cell therapy, a maintained tissue patch could serve as a continued source of such beneficial paracrine signaling to the native heart tissue (Central Illustration). As our understanding of exosomal biology advances, patches can be engineered to optimize this signaling for cardiac regeneration. Use of genome-editing technologies may further enhance the potency and functional integration of delivered cells. Major challenges will be to address the potential arrhythmogenicity risks associated with a large graft. With exciting translational prospects ahead, future studies to optimize engineered cardiac tissue therapies in large animals and decipher the mechanisms of action are fully warranted.

Central Illustration. Overview of Strategies to Overcome the Roadblocks in Cardiac Cell Therapy.

The delivery of types of cells generally resulted in modest therapeutic benefits. Transplantation of prefabricated engineered heart tissue (e.g., cardiac tissue patch containing pluripotent stem cell–derived tri-cardiac cells) could enhance the therapeutic effects by an increased engraftment rate, which in turn, results in prolonged release of cytokines, reduction in left ventricular (LV) dilation and LV wall stresses. A major challenge that remains to be addressed is the potential arrhythmia risks associated with a large graft.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge NIH support of their research, the NIH Progenitor Cell Biology Consortium (grant HL099997), and the Symposium held at University of Alabama-Birmingham in March 2016. This work was a product of discussions at the NIH Progenitor Cell Biology Consortium Cardiovascular Tissue Engineering Symposium, March 2016.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- BMC

bone marrow–derived cell

- CM

cardiomyocytes

- CDC

cardiosphere-derived cell

- EC

endothelial cell

- IC

intracoronary

- IM

intramyocardial

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- PSC

pluripotent stem cell

Footnotes

Disclosures: Garry: Boston Scientific, NorthStar Genomics; Hare: Vestion, Longeveron LLC; All other authors had nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nguyen PK, Rhee JW, Wu JC. Adult stem cell therapy and heart failure, 2000 to 2016: a systematic review. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:831–41. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lalit PA, Salick MR, Nelson DO, et al. Lineage reprogramming of fibroblasts into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells by defined factors. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:354–67. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Cao N, Huang Y, et al. Expandable cardiovascular progenitor cells reprogrammed from fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:368–81. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackman CP, Carlson AL, Bursac N. Dynamic culture yields engineered myocardium with near-adult functional output. Biomaterials. 2016;111:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackman CP, Shadrin IY, Carlson AL, Bursac N. Human cardiac tissue engineering: from pluripotent stem cells to heart repair. Curr Opin Chem Eng. 2015;7:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang D, Shadrin IY, Lam J, Xian HQ, Snodgrass HR, Bursac N. Tissue-engineered cardiac patch for advanced functional maturation of human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5813–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Klos M, Wilson GF, et al. Extracellular matrix promotes highly efficient cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells: the matrix sandwich method. Circ Res. 2012;111:1125–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.273144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lian X, Hsiao C, Wilson G, et al. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1848–57. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200250109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang L, Geng Z, Nickel T, et al. Differentiation of human induced-pluripotent stem cells into smooth-muscle cells: two novel protocols. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye L, Zhang S, Greder L, et al. Effective cardiac myocyte differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells requires VEGF. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S, Dutton JR, Su L, Zhang J, Ye L. The influence of a spatiotemporal 3D environment on endothelial cell differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35:3786–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campagnolo P, Tsai TN, Hong X, et al. c-Kit+ progenitors generate vascular cells for tissue-engineered grafts through modulation of the Wnt/Klf4 pathway. Biomaterials. 2015;60:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorn GW, II, Vega RB, Kelly DP. Mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics in the developing and diseased heart. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1981–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.269894.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorn GW, II, Kitsis RN. The mitochondrial dynamism-mitophagy-cell death interactome: multiple roles performed by members of a mitochondrial molecular ensemble. Circ Res. 2015;116:167–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung S, Dzeja PP, Faustino RS, Perez-Terzic C, Behfar A, Terzic A. Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is required for the cardiac differentiation of stem cells. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4(Suppl 1):S60–7. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasahara A, Cipolat S, Chen Y, Dorn GW, II, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial fusion directs cardiomyocyte differentiation via calcineurin and Notch signaling. Science. 2013;342:734–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1241359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wendel JS, Ye L, Zhang P, Tranquillo RT, Zhang JJ. Functional consequences of a tissue-engineered myocardial patch for cardiac repair in a rat infarct model. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:1325–35. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruwhof C, van Wamel AE, Egas JM, van der Laarse A. Cyclic stretch induces the release of growth promoting factors from cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;208:89–98. doi: 10.1023/a:1007046105745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Wamel AJ, Ruwhof C, van der Valk-Kokshoorn LJ, Schrier PI, van der Laarse A. Stretch-induced paracrine hypertrophic stimuli increase TGF-beta1 expression in cardiomyocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;236:147–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1016138813353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masumoto H, Matsuo T, Yamamizu K, et al. Pluripotent stem cell-engineered cell sheets reassembled with defined cardiovascular populations ameliorate reduction in infarct heart function through cardiomyocyte-mediated neovascularization. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1196–205. doi: 10.1002/stem.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin CM, Meeson AP, Robertson SM, et al. Persistent expression of the ATP-binding cassette transporter, Abcg2, identifies cardiac SP cells in the developing and adult heart. Dev Biol. 2004;265:262–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Hu Q, Nakamura Y, et al. The role of the sca-1+/CD31− cardiac progenitor cell population in postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1779–88. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tokita Y, Tang XL, Li Q, et al. Repeated administrations of cardiac progenitor cells are markedly more effective than a single administration: a new paradigm in cell therapy. Circ Res. 2016;119:635–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hare JM, DiFede DL, Castellanos AM, et al. Randomized comparison of allogeneic versus autologous mesenchymal stem cells for nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: POSEIDON-DCM Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:526–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karantalis V, Suncion-Loescher VY, Bagno L, et al. Synergistic effects of combined cell therapy for chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1990–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng L, Hu Q, Wang X, et al. Bioenergetic and functional consequences of bone marrow-derived multipotent progenitor cell transplantation in hearts with postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 2007;115:1866–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y, Wysoczynski M, Nong Y, et al. Repeated doses of cardiac mesenchymal cells are therapeutically superior to a single dose in mice with old myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2017;112:18. doi: 10.1007/s00395-017-0606-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ban K, Park HJ, Kim S, et al. Cell therapy with embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes encapsulated in injectable nanomatrix gel enhances cell engraftment and promotes cardiac repair. ACS Nano. 2014;8:10815–25. doi: 10.1021/nn504617g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Segers VF, Lee RT. Biomaterials to enhance stem cell function in the heart. Circ Res. 2011;109:910–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.249052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vunjak-Novakovic G, Lui KO, Tandon N, Chien KR. Bioengineering heart muscle: a paradigm for regenerative medicine. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2011;13:245–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071910-124701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao T, Zhang ZN, Rong Z, Xu Y. Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;474:212–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao T, Zhang ZN, Westenskow PD, et al. Humanized mice reveal differential immunogenicity of cells derived from autologous induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:353–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Araki R, Uda M, Hoki Y, et al. Negligible immunogenicity of terminally differentiated cells derived from induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2013;494:100–4. doi: 10.1038/nature11807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guha P, Morgan JW, Mostoslavsky G, Rodrigues NP, Boyd AS. Lack of immune response to differentiated cells derived from syngeneic induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:407–12. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abrahimi P, Chang WG, Kluger MS, et al. Efficient gene disruption in cultured primary human endothelial cells by CRISPR/Cas9. Circ Res. 2015;117:121–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.306290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiao SL, Kirkiles-Smith NC, Shepherd BR, McNiff JM, Carr EJ, Pober JS. Human effector memory CD4+ T cells directly recognize allogeneic endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:4397–404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong KU, Guo Y, Li QH, et al. c-kit+ Cardiac stem cells alleviate post-myocardial infarction left ventricular dysfunction despite poor engraftment and negligible retention in the recipient heart. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malliaras K, Li TS, Luthringer D, et al. Safety and efficacy of allogeneic cell therapy in infarcted rats transplanted with mismatched cardiosphere-derived cells. Circulation. 2012;125:100–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.042598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanganalmath SK, Bolli R. Cell therapy for heart failure: a comprehensive overview of experimental and clinical studies, current challenges, and future directions. Circ Res. 2013;113:810–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ismahil MA, Hamid T, Bansal SS, Patel B, Kingery JR, Prabhu SD. Remodeling of the mononuclear phagocyte network underlies chronic inflammation and disease progression in heart failure: critical importance of the cardiosplenic axis. Circ Res. 2014;114:266–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nevers T, Salvador AM, Grodecki-Pena A, et al. Left ventricular T-cell recruitment contributes to the pathogenesis of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:776–87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prabhu SD, Frangogiannis NG. The biological basis for cardiac repair after myocardial infarction: from inflammation to fibrosis. Circ Res. 2016;119:91–112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sager HB, Hulsmans M, Lavine KJ, et al. Proliferation and recruitment contribute to myocardial macrophage expansion in chronic heart failure. Circ Res. 2016;119:853–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamid T, Xu Y, Ismahil MA, et al. TNF receptor signaling inhibits cardiomyogenic differentiation of cardiac stem cells and promotes a neuroadrenergic-like fate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311:H1189–H1201. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00904.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiba Y, Gomibuchi T, Seto T, et al. Allogeneic transplantation of iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerates primate hearts. Nature. 2016;538:388–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiss JN, Qu Z, Chen PS, et al. The dynamics of cardiac fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;112:1232–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.529545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fontes MS, van Veen TA, de Bakker JM, van Rijen HV. Functional consequences of abnormal Cx43 expression in the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:2020–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis LM, Rodefeld ME, Green K, Beyer EC, Saffitz JE. Gap junction protein phenotypes of the human heart and conduction system. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1995;6:813–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1995.tb00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dupont E, Matsushita T, Kaba RA, et al. Altered connexin expression in human congestive heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:359–71. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kostin S, Rieger M, Dammer S, et al. Gap junction remodeling and altered connexin43 expression in the failing human heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;242:135–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roell W, Lewalter T, Sasse P, et al. Engraftment of connexin 43-expressing cells prevents post-infarct arrhythmia. Nature. 2007;450:819–24. doi: 10.1038/nature06321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gerbin KA, Yang X, Murry CE, Coulombe KL. Enhanced electrical integration of engineered human myocardium via intramyocardial versus epicardial delivery in infarcted rat hearts. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chong JJ, Yang X, Don CW, et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510:273–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiong Q, Ye L, Zhang P, et al. Bioenergetic and functional consequences of cellular therapy: activation of endogenous cardiovascular progenitor cells. Circ Res. 2012;111:455–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiong Q, Ye L, Zhang P, et al. Functional consequences of human induced pluripotent stem cell therapy: myocardial ATP turnover rate in the in vivo swine heart with postinfarction remodeling. Circulation. 2013;127:997–1008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bolognese L, Neskovic AN, Parodi G, et al. Left ventricular remodeling after primary coronary angioplasty: patterns of left ventricular dilation and long-term prognostic implications. Circulation. 2002;106:2351–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000036014.90197.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu Q, Wang X, Lee J, et al. Profound bioenergetic abnormalities in peri-infarct myocardial regions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H648–57. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01387.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feygin J, Mansoor A, Eckman P, Swingen C, Zhang J. Functional and bioenergetic modulations in the infarct border zone following autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1772–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00242.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kobayashi T, Yamaguchi T, Hamanaka S, et al. Generation of rat pancreas in mouse by interspecific blastocyst injection of pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;142:787–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Usui J, Kobayashi T, Yamaguchi T, Knisely AS, Nishinakamura R, Nakauchi H. Generation of kidney from pluripotent stem cells via blastocyst complementation. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:2417–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bort R, Signore M, Tremblay K, Martinez Barbera JP, Zaret KS. Hex homeobox gene controls the transition of the endoderm to a pseudostratified, cell emergent epithelium for liver bud development. Dev Biol. 2006;290:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsunari H, Nagashima H, Watanabe M, et al. Blastocyst complementation generates exogenic pancreas in vivo in apancreatic cloned pigs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4557–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222902110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Berlo JH, Kanisicak O, Maillet M, et al. c-kit+ cells minimally contribute cardiomyocytes to the heart. Nature. 2014;509:337–41. doi: 10.1038/nature13309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Berlo JH, Molkentin JD. Most of the dust has settled: cKit+ progenitor cells are an irrelevant source of cardiac myocytes in vivo. Circ Res. 2016;118:17–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hatzistergos KE, Takeuchi LM, Saur D, et al. cKit+ cardiac progenitors of neural crest origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:13051–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517201112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mohamed TM, Stone NR, Berry EC, et al. Chemical enhancement of in vitro and in vivo direct cardiac reprogramming. Circulation. 2017;135:978–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nam YJ, Song K, Olson EN. Heart repair by cardiac reprogramming. Nat Med. 2013;19:413–5. doi: 10.1038/nm.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Srivastava D, Yu P. Recent advances in direct cardiac reprogramming. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2015;34:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kanisicak O, Khalil H, Ivey MJ, et al. Genetic lineage tracing defines myofibroblast origin and function in the injured heart. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12260. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moore-Morris T, Cattaneo P, Puceat M, Evans SM. Origins of cardiac fibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;91:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Y, Dal-Pra S, Mirotsou M, et al. Tissue-engineered 3-dimensional (3D) microenvironment enhances the direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes by microRNAs. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38815. doi: 10.1038/srep38815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sia J, Yu P, Srivastava D, Li S. Effect of biophysical cues on reprogramming to cardiomyocytes. Biomaterials. 2016;103:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bursac N, Kirkton RD, McSpadden LC, Liau B. Characterizing functional stem cell-cardiomyocyte interactions. Regen Med. 2010;5:87–105. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, et al. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (CADUCEUS): a prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:895–904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.A futile cycle in cell therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:291. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ishigami S, Ohtsuki S, Tarui S, et al. Intracoronary autologous cardiac progenitor cell transfer in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome: the TICAP prospective phase 1 controlled trial. Circ Res. 2015;116:653–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tarui S, Ishigami S, Ousaka D, et al. Transcoronary infusion of cardiac progenitor cells in hypoplastic left heart syndrome: three-year follow-up of the Transcoronary Infusion of Cardiac Progenitor Cells in Patients With Single-Ventricle Physiology (TICAP) trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1198–1207. 1208.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ishigami S, Ohtsuki S, Eitoku T, et al. Intracoronary cardiac progenitor cells in single ventricle physiology: the PERSEUS (Cardiac Progenitor Cell Infusion to Treat Univentricular Heart Disease) Randomized Phase 2 Trial. Circ Res. 2017;120:1162–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Choudhury T, Mozid A, Hamshere S, et al. An exploratory randomized control study of combination cytokine and adult autologous bone marrow progenitor cell administration in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy: the REGENERATE-IHD clinical trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:138–47. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bartunek J, Terzic A, Davison BA, et al. Cardiopoietic cell therapy for advanced ischaemic heart failure: results at 39 weeks of the prospective, randomized, double blind, sham-controlled CHART-1 clinical trial. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:648–60. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Butler J, Epstein SE, Greene SJ, et al. Intravenous allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for nonischemic cardiomyopathy: safety and efficacy results of a phase II-A randomized trial. Circ Res. 2017;120:332–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wojakowski W, Jadczyk T, Michalewska-Wludarczyk A, et al. Effects of transendocardial delivery of bone marrow-derived CD133+ cells on left ventricle perfusion and function in patients with refractory angina: final results of randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled REGENT-VSEL Trial. Circ Res. 2017;120:670–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miyagawa S, Domae K, Yoshikawa Y, et al. Phase I clinical trial of autologous stem cell-sheet transplantation therapy for treating cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e003918. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Müller-Ehmsen J, et al. Intracoronary autologous bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST-2 randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur Heart J. 2017 Apr 19; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx188. E-pub ahead of print https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx188. [DOI] [PubMed]