Abstract

Objective

We examined the cultural relevance of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) in the design of a physical activity intervention for African-American women.

Methods

A qualitative study design was used. Twenty-five African-American women (Mean age = 38.5 years, Mean BMI = 39.4 kg·m2) were enrolled in a series of focus groups (N = 9) to elucidate how 5 SCT constructs (ie, Behavioral Capability, Outcome Expectations, Self-efficacy, Self-regulation, Social Support) can be culturally tailored in the design of a physical activity program for African-American women.

Results

For the construct of Behavioral Capability, participants were generally unaware of the amount, intensity, and types of physical activity needed for health benefits. Outcome Expectations associated with physical activity included increased energy, improved health, weight loss, and positive role modeling behaviors. Constructs of Self-efficacy and Self-regulation were elicited through the women perceiving themselves as a primary barrier to physical activity. Participants endorsed the need of a strong social support component and identified a variety of acceptable sources to include in a physical activity program (ie, family, friends, other program participants).

Conclusions

Findings explicate the utility of SCT as a behavioral change theoretical basis for tailoring physical activity programs to African-American women.

Keywords: behavioral theory, black women, exercise, cultural tailoring, social cognitive theory

African-American (AA) women are one of the least physically active demographic groups in the United Sates (US). Self-report data from the 2000–2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) show that only 36% of AA women achieve the national guidelines for aerobic physical activity (PA) (ie, 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity PA, 75 minutes of vigorous PA, or combination equivalent of the 2 intensities).1 In comparison, 50% of the US population as whole, 49% of AA men, and 49% of white women achieve this recommendation. The low PA levels of AA women are concerning because of their disproportional burden of PA-related cardiometabolic disease conditions. For example, national data reveal that 57% are obese (BMI≥30 kg·m2; compared to 32.8% of white women and 44.4% of Hispanic women),2 with nearly half (48.3%) of all AA women in the US having cardiovascular disease (compared to 31.9% of white women and 32.5% of Hispanic women)3 and 9.9% having a diagnosis of type II diabetes (compared to 5.3 % of white women and 8.1% to 9.6% of Hispanic women depending on country of origin).4 There is an urgent need to implement effective strategies to increase PA and attenuate PA-related health disparities among AA women.

Behavioral interventions are essential to increase PA and reduce PA-related health disparities in this high-risk population. When designing PA interventions, important attention should be given to the use of behavioral theory, as a breadth of literature shows that theoretically-based behavior change interventions are more effective than those that are non-theoretical.5–8 Moreover, use of the appropriate behavioral theory is an important part of understanding a health problem that requires intervention.9 Utilizing a theoretical approach to define the problem of insufficient PA among AA women allows for the identification of causative factors, mechanisms that connect the causal factors, and the context under which the mechanisms operate.9 Conceptualization of these factors provides a framework for researchers to leverage when developing behavioral intervention strategies to address this public health concern.

A useful theory in PA promotion research is Social Cognitive Theory (SCT).10–12 The SCT explains behavior in a dynamic and reciprocal model in which personal factors (beliefs, attitudes), the environment (social and physical) and the behavior itself all interact to produce a behavior.13 The applicability of SCT to promote PA among AA women is of particular relevance, as it includes several evidence-based PA promotion constructs (ie, Self-regulation, Self-efficacy, and Social Support).14–16 These constructs can be culturally tailored to address deeply-rooted aspects of AA culture (ie, of collectivism/ethic of care, experiential knowledge, and kinship) for the promotion of PA among AA women.17 However, few researchers have explicated the utility of the SCT in the design of culturally relevant PA programs for AA women. A 2014 review of PA interventions for AAs18 revealed that 7 of 16 studies used SCT as a theoretical basis for activities. Among the 6 SCT-based studies targeting AA women, 419–22 provided in-depth data on the how the intervention was culturally tailored, and only one19 thoroughly described the congruence between the SCT constructs underpinning intervention activities and the culturally tailored PA promotion strategies. This underscores the need for researchers to be clear in delineating how behavioral theory can be paired with culturally relevant intervention strategies to promote PA.

In this paper, we describe a series of focus groups with AA women designed to refine a PA intervention prior to large-scale implementation. These qualitative assessments focused on: (1) collecting empirically-driven data regarding AA women’s perceptions, manifestations, and determinants of PA to improve clarity and cultural relevance of our PA program; and (2) enhancing the theoretical fidelity of the 5 SCT constructs among AA women targeted by the PA intervention – Self-efficacy, Self-regulation, Behavioral Capability, Outcome Expectations, and Social Support. Table 1 describes our operational definitions for these SCT constructs and the topics we explored to elucidate the utility of SCT in the design of a PA program for AA women. Results illustrate how researchers can translate SCT constructs into practice when developing a PA promotion program for AA women.

Table 1.

Operational Definitions and Key Topics Examined for the 5 Social Cognitive Theory Constructs Explored during Focus Group Sessions with African-American (AA) Women

| SCT Construct | Operational Definition | Key Topics Explored during Focus Group Discussions |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Capability | Knowledge and skill to perform physical activity (PA) | Knowledge regarding the duration and intensity of PA needed for health benefits What is meant by the terms “exercise” and “PA” Knowledge on what activities constitute as PA or exercise |

| Outcome Expectations | Beliefs, values, and anticipated outcomes of performing regular PA | Benefits of PA Values placed on the benefits of PA Why participants would want to perform PA |

| Self-efficacy | Confidence in the ability to take action and overcome barriers to perform PA | Previous experiences with PA Barriers to PA Strategies on how to overcome barriers PA that AA enjoy performing |

| Self-regulation | Ability to manage PA and exercise behaviors through self-monitoring, goal setting, and self-reward. | General feelings and connotations associated with the terms “exercise” and “PA Strategies on how AA women can incorporate PA into their daily schedule Self-monitoring and goal setting Rewards/reinforcements for PA |

| Social Support | Extent to which significant referents (family, friends, peers) approve, encourage, and/or influence performance of PA | Sources of social support for PA How to identify and find social support for PA How to incorporate social support into a PA program |

METHODS

Study Design

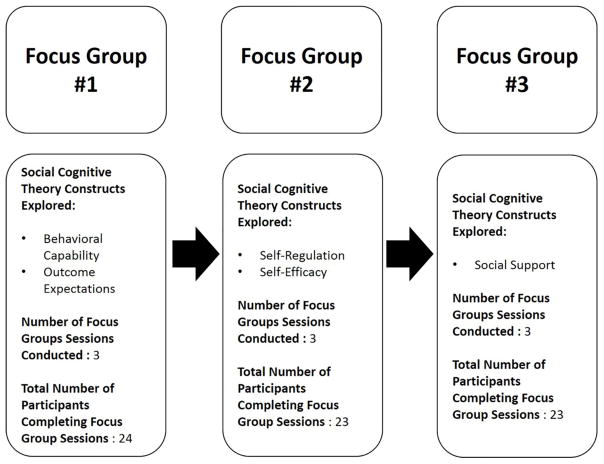

A qualitative study design was used. Twenty-five sedentary and obese AA women were enrolled and attend a series of 3 focus groups conducted over a 6-week period during March–May 2016. Each focus group was designed to target specific SCT constructs (see section below on the development of the focus group guides). To achieve the goal of having 6–10 women per focus group session, each focus group (ie, focus group #1, focus group #2, and focus group #3) was offered on 3 separate dates, for a total of 9 focus groups. Participants attended focus groups #1 through #3 in sequential order, as the questions for each focus group were designed to build on the prior session. Focus group #1 was offered during weeks 1–2 of the study, focus group #2 during weeks 2–4, and focus group #3 during weeks 5–6. Figure 1 provides a diagram illustrating the study design. Focus groups were designed to be approximately 1 to 1–1/2 hours in duration. This study design allowed us to collect in-depth data on the 5 SCT constructs, while also being considerate of participant time and burden. Collecting the data in less than 3 focus groups would have resulted in discussion sessions that were of long duration (ie, approximately 3 to 4–1/2 hours) and may have negatively influenced the quality of our data due to participant fatigue and/or loss of interest.23

Figure 1.

Diagram Illustrating the Study Design

Development of Focus Group Guides

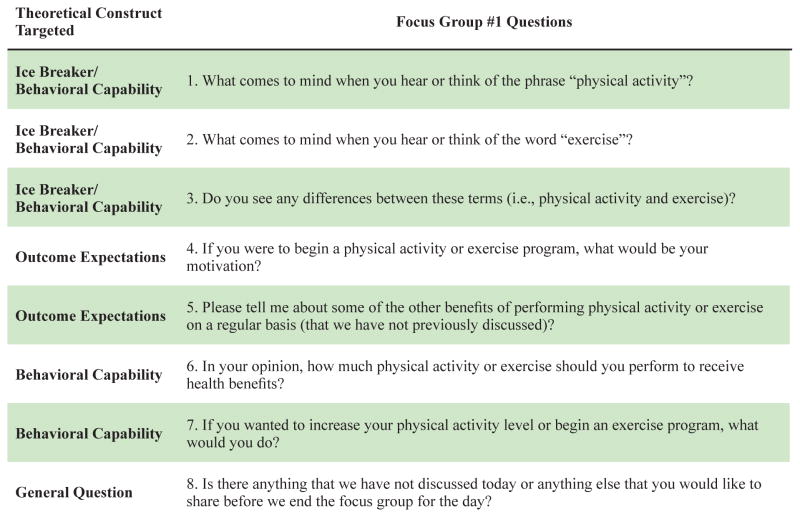

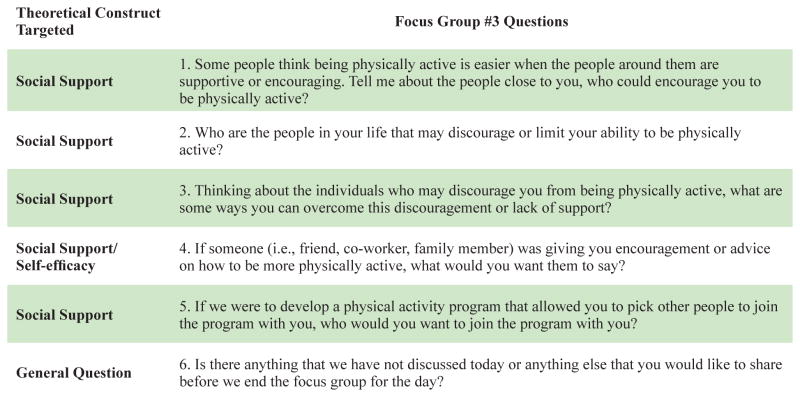

Focus group guides were derived from our previous PA promotion work with AA women17,24–28 and a critical review of the extant literature. In particular, the guides were designed to: (1) examine specific SCT constructs (Table 1) underpinning a PA program previously developed by the research team; and (2) elucidate how these constructs can be optimized in the design of a culturally relevant PA program for AA women. Initial drafts of the focus group guides were developed by the PI and circulated to 3 of the co-authors (BEA, SPH, and CK) for critical scientific review. This review focused on evaluating theoretical fidelity and cultural relevance of the questions, as well as examining the structure and wording of the guides. Based on feedback, the PI revised the focus group guides and re-circulated the guides to the 3 co-investigators for a second review. Further feedback was used to refine the focus group guides. The final stage of focus group guide development consisted of the AA community member (LMM) on the research team reviewing the focus group guides for clarity and cultural relevance. The final guides used in the study, presented in Figures 2–4, represent the collective expertise of all 5 members of the research team. No additional pilot-testing of the focus group guides was conducted. No modifications were made to the guides during study implementation.

Figure 2.

Focus Group Guide Used in the Focus Group #1 Sessions

Figure 4.

Focus Group Guide Used in the Focus Group #3 Sessions

Focus group #1 focused on the theoretical constructs of Behavioral Capability and Outcomes Expectations, focus group #2 explored the constructs of Self-regulation and Self-efficacy, and focus group #3 targeted Social Support (Figure 1). Topics examined in each focus group session were designed to expanded-on and build-off topics discussed in previous sessions. For example, focus group #1 examined participants’ perceptions about PA and exercise, as well as their knowledge and skills associated with engaging in PA, which were important precursors for the topics explored in focus groups #2 (ie, self-regulatory behaviors and barriers for PA) and #3 (sources of social support for PA). This sequential progression of focus groups helped ensure that questions posed to participants were not leading and would not results in a biased answers based on previous discussion questions.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were a purposeful sample of AA women recruited from the metropolitan area of Phoenix, Arizona during spring 2016. Multiple strategies were used to recruit participants, including advertisements on social media postings, email listservs, newsletters, and local websites targeting the AA community. Women were eligible to participate if they: (1) self-reported as AA; (2) were between the ages of 24 and 49 years; (3) had a BMI ≥ 30 kg·m2; and (4) performed <60 minutes/week of moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA according to the 2-item Exercise Vital Sign questionnaire, which has been validated against accelerometers for assessment of PA among AA women (ie, sensitivity, specificity, and negative and positive predictive values for the Exercise Vital sign to correctly identify AA women who achieve national PA recommendations based on accelerometer-measured PA range from 27%–33%, 74%–89%, 39%–59%, and 68%–70%, respectfully).29 No further inclusion/exclusion criteria were specified.

Women interested in participating in the study contacted study staff either by email or telephone after becoming aware of the study (ie, after viewing the recruitment materials or from word-of-mouth), and were screened for eligibility using a brief telephone screener. After screening, eligible women were scheduled for 3 focus group sessions. Participants were able to select any of the available focus group dates to attend, but were allowed to attend only one group focused on each topic (ie, participants could only attend one focus group #1, one focus group #2, and one focus group #3). Accordingly, participants did not attend each focus group session with the exact same group of women that attended their focus group #1 session; however, there was some overlap among participants across the focus group sessions.

Focus Group Procedures

Trained facilitators led the focus groups. The African-American community member of the study (LMM) led 8 of the 9 groups. One focus group #2 session was led by the PI (RPJ), due to an unexpected event that occurred the day of a schedule focus group session requiring the AA facilitator to be absent. At the first focus group session, written informed consent was obtained. Participants also completed a short demographic questionnaire to provide information on age, marital status, annual household income, number of children residing in household, and education attainment. Height and weight data also were obtained to calculate body mass index (BMI). Height was measured to the nearest quarter inch using a Seca 231 portable stadiometer. Weight was measured to the nearest tenth of a pound using a Tanita HD-351 digital scale. BMI was computed as weight in pounds divided by height in inches squared. To ensure consistency of measurements, the same staff member performed height and weight measurements of all participants. Given that time was dedicated to obtaining informed consent, demographic, and anthropometric data at the first focus group session, qualitative data collection procedures for the focus group #1 sessions were intentionally designed to be shorter in duration than for the 2 other focus group sessions; this ensured participant burden did not exceed 1–1/2 hours for the focus group session. Participants were compensated $20 for each focus group they attended (ie, participants received $60 for attending all 3 focus groups).

Data Analysis

Focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. All participants were assigned an identification number for data reporting purposes and transcripts were imported into NVivo software (version 11) for analysis. Directed content analysis30,31 was used to analyze the focus group data. This method was selected because it provides a useful method to validate and extend knowledge on the theoretical framework.31 Moreover, it allows for the constructs of SCT to guide the reporting and discussion of the qualitative data,31 which was the research team’s desired format to present focus group findings.

Prior to analyzing data, an initial codebook of primary deductive codes based on the 5 SCT constructs explored in focus groups sessions was developed by the PI. Secondary codes consisted of key concepts examined under each SCT construct (Table 1). Coding was completed using a 3-phase approach. First, the PI independently reviewed all transcripts and applied the deductive codes. Second, 2 other members of the research team (BEA and CK) independently reviewed the coded data to ensure congruence between the deductive codes and the qualitative narratives of participants. Third, the 3 researchers discussed the coded data as a group to reach consensus about the most appropriate coding of the data. After the coding meeting was complete, the PI again reviewed all transcripts and ensured deductive codes were applied appropriately to the qualitative data. After all data were coded, the PI reviewed the coded data for repetitive themes within and across the specific SCT constructs explored. These repetitive themes were the basis for which findings were derived from the qualitative assessments. The final phase of data analysis occurred when the local community member of the research team (LMM) reviewed the results and verified the team’s interpretation of the data. Due to the collaborative nature of data analysis, a formal statistic of inter-rater reliability was not calculated. However, findings reported reflect a consensus interpretation of the study data by all 5 members of the research team. Quantitative analysis of demographic data was completed using SPSS version 23.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Participants had a mean age of 38.5 (SD=7.8) years and mean BMI of 39.4 (SD=7.3) kg·m2. The majority of women were never married (N = 18, 72%) and had obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher (N = 19, 76%). Forty-six percent (N = 11) of women had at least one child living in their household and all (N = 25, 100%) reported being employed outside of the home. Household income level varied, with the majority (N = 15, 60%) reporting an annual household income of $50,000 or less. Eight participants had a household income between $50,001 and $100,000 and 2 reported income of >$100,000. The mean number of minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous PA self-reported by participants (based on the Exercise Vital Sign Questionnaire) during screening procedures was 17 minutes (SD=17.1; Median= 0, Range 0 – 50).

Focus Group Protocol Adherence

Adherence to study protocol was high, with 80% (N = 20) of participants attending all 3 focus group sessions. The remaining participants (N = 5, 20%) attended 2 out of the 3 focus group sessions. A total of 24 women completed the Focus Group #1 session, 23 completed Focus Group #2, and 23 completed Focus Group #3. The size of the individual focus group sessions ranged 5 to 11 women, with 8 being the median number of participants attending each focus group. The average duration of focus group sessions was 62 minutes (SD=16.6 minutes), with individual group sessions ranging 30 (ie, focus group #1 session) to 75 minutes (focus group #2 session).

Findings

Qualitative findings are presented according to each specific construct salient to the SCT. Table 2 provides a brief description of the key qualitative findings and implications for how these findings can be translated into practice.

Table 2.

Key Themes from Focus Group Sessions and Strategies to Translate Findings into a Physical Activity (PA) Program for African-American (AA) Women

| SCT Construct | Key Themes | Translations into Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Capability |

|

|

| Outcome Expectations |

|

|

| Self-efficacy |

|

|

| Social Support |

|

|

| Self-regulation |

|

|

Behavioral capability

Data collected for the construct of Behavioral Capability focused on the knowledge and skills necessary to engage in a physically active lifestyle. Exploration of these topics was essential to ensure the PA program is tailored to participants’ knowledge and skill level for PA. The first topic examined was participant perceptions on how much PA is needed to receive health benefits. Responses varied substantially in regard to intensity, duration, and frequency. Example responses included:

“I think about 4 days a week, about an hour of high impact of some sort. About 4 days”

(participant 25, focus group #1)

and

“I would think at least 90 minutes a week would be beneficial.”

(participant 17, focus group #1)

A number of participants reported not knowing how much PA was needed to receive health benefits. There also appeared to be a lack awareness about the National Physical Activity Guidelines for aerobic PA (ie, 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity PA, 75 minutes of vigorous PA, or combination equivalent of the 2 intensities), as only one participant (ie, participant 23, focus group #1) across the 3 focus groups examining this topic was able to identify PA levels similar to the National PA Guidelines. She stated:

“They say 30 minutes, 5 days a week. Isn’t that the going count? That’s what I hear.”

Among some women, there was a belief that the level of PA necessary to receive health benefits varied according to a woman’s ethnic background, weight status, and previous experience with PA. For example, participant 15 (focus group #1) stated the following when expressing how she believed the amount of PA needed for health benefits is based on a woman’s ethnic background:

“…it’s [referring the PA for health benefits] really tailored to the individual because there’s, ‘What’s your racial history?’ And not just what you might think you see, but what’s your history because that can contribute to your health benefits.”

Similarly, participant 19 (focus group #1) expressed the following when describing how she believed previous PA experience influenced the amount of PA needed for health benefits:

“I honestly feel like it kind of depends on where you’re at and where you start. At least that’s how I think about it for myself.”

Perceptions regarding the differences between PA and exercise were also explored, as our previous research indicates these terms are a point of confusion for many women. During the early stages of discussion, participants described PA and exercise as interchangeable. This was demonstrated by participants automatically using one term when specifically asked about the other. For example, when asked about the term “physical activity,” participant 23 (focus group #1) stated:

“I’m trying to consider that sometimes exercise is gardening or yard work; we don’t think of that. Exercising is something you have to do at the gym, or running several miles, or not thinking about things that we do enjoy doing as being physically active.”

As the discussions progressed and the facilitator probed participants further, women began to differentiate between the 2 terms. As participant 4 (focus group #1) explained:

“As soon as you said physical activity, we interpreted it as exercise, but they really are very different. Physical activity could just be adding a couple extra steps to your – parking farther, or getting up on a break at work and actually walking around the building, or just adding extra stuff; rather than exercising being more intentional, and planned, and scheduled.”

By the end of the conversation, participants in all 3 focus groups reached a consensus that exercise was a more structured form of PA, and that PA could consist of a variety of activities, not just exercise.

A final topic examined for the construct of Behavioral Capability was the information and support needed to initiate a PA or exercise program (a topic also closely aligned with the construct of self-regulation). Participants expressed the desire to receive specific, detailed information regarding the behavioral target of a PA program, and a specific plan on how to achieve the PA goal. They emphasized that receiving a structured exercise or PA plan would help provide the knowledge and skills necessary to be more physically active. Participant 24 (focus group #1) illustrated this using the following analogy:

“I think the biggest thing would be a plan. You think of meal plans, and it tells you what to eat for breakfast on Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday and Thursday. And for me, I would need something to show me what exercises to do on Monday, which ones to do on Tuesday…”

A final topic that emerged as a key factor needed to initiate a PA program was social support, as women reported the need for encouragement and accountability to be successful with beginning a PA routine (discussed in-depth in a subsequent section of the paper).

Outcome expectations

Women described various anticipated outcomes associated with adopting a more physically active lifestyle. Improved health emerged across all focus group sessions, particularly in reference to reduced risk for chronic disease conditions, including type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure. Other health outcomes participants associated with PA included reduced stress and improved sleep. As discussions on the topic of PA and health continued, individual participants began to summarize the desired health benefits from PA using the following statements:

“Ultimately it’s just increased health. Be healthier, you’ll feel better, have more energy. Better response to stress, all those kinds of things”

(participant 8, focus group #1)

and

“For me, the motivating factor is I want to live. You know. Straight up, I want to live…you see people who are passing away at your age, I guess. And, you know, because of heart attacks or, you know, things, diabetes or whatever these things, all these health obstacles and just different challenges because of, I’ll say laziness, just being real about it, you know.”

(participant 2, focus group #1)

Another outcome expectation of PA was vanity related to weight loss. Participant 4 stated (focus group #1):

“My motivation would be clothes, actually. Yeah, and not having to buy plus size clothes, and not having to spend ridiculously large amounts of money for clothing.”

There was some discussion among participants as to whether health or weight loss was a more valued outcome for increasing PA. Some women discussed health as a more important motivator, whereas others stated that improving their physical appearance was more important (with health benefits being secondary). Participant 21 (focus group #1) expressed the following when asked her motivation for being physically active:

“I would say meeting that weight-loss goal. To me, that’s paramount, and then it seems like even the health is an extra benefit.”

Another participant (participant 23, focus group #1) further elucidated this sentiment saying:

“We go by what we see first [referring to body size], and then what we feel second [referring to improved health]… I think most people function that way. We’re all visual humans.”

A third anticipated outcome for adopting a physically active lifestyle revolved around increased energy and ability to engage in more activities with their family and/or community. Participant 9 (focus group #1) expressed the following when describing the benefits of increased energy:

“Trying to keep up with family members who are younger. Running with the kids, and playing, and jumping, and having a good time.”

Another women (participant 21, focus group #1) stated that being more physically active would allow her to do more activities with her family:

“For me, I think it comes to normalcy, I guess. So normalcy [referring to the benefits of being active] to be in a category with the rest of my peers, my family, and being able to maybe keep up with family – with my son and my husband – and being able to do those things and not be exhausted or not sit out the ride or sit out the trip for whatever reason.”

Similarly related, several women reported that their desire to be physically active was associated with being a good role model to others, particularly their family. Quotes illustrating this sentiment include:

“I have children. They’re teenagers, and I’m trying to break out of the statistics category regarding African-American women [referring to cardiometabolic health disparities]”

(participant 10, focus group #1)

and

“I would say setting a good example for my children is another motivating factor.”

(participant 11, focus group #1)

Self-efficacy

When exploring the construct of Self-efficacy, we focused on participants’ previous experiences with PA, barriers to PA and self-identified strategies to overcome them, and their preferences for PA. From a theoretical perspective, past experiences with a specific behavior, including PA, are some of the most important factors determining self-efficacy for that behavior. Gaining an understanding of women’s previous experiences with PA allows for the design of intervention activities to leverage the positive experiences (to enhance self-efficacy) and negate the negative experiences (that may decrease self-efficacy for PA). Similarly, incorporating physical activities that AA women enjoy performing into a PA program can further increase self-efficacy for PA engagement. Barriers to PA and ways to overcome barriers were explored so we could identify strategies to increase confidence in participants’ ability to overcome common barriers and successfully increase PA.

When queried about their past experiences with PA, most participants recalled being physically active in the past, both as a child and an adult. As children, women stated PA was encouraged by their family members, primarily through play activities including playing tag, sports, and other types of physically active games outside. Women generally associated that time of life with happiness and enjoyment. Participant 10 (focus group #2) described her experiences with PA as a child with the following:

“For our childhood, coming up, we were more active because everything was done outside. You had your playtime. Parents, grandparents made you go outside to get off them. But that was something we enjoyed…and it wasn’t just you and your brother and sister, but it was more like a community thing. Everybody knew, ‘Hey, at this certain time we’re all coming together.’”

Interestingly, few women reported negative previous experiences with PA or exercise. Among those who did, the negative experiences were related to structured exercise and/or sporting activities that occurred during adolescence or adulthood. Reasons for these negative experiences included being forced to perform activities they did not want to perform and being uncomfortable with PA due to early onset of physical development, which resulted in embarrassment and teasing from other children. Participant 11 (focus group #2) illustrated this by stating:

“As a young kid I was developed early, so the idea of running and jogging and doing jumping jacks in front of a whole bunch of boys, I would never. So I would literally fake ailments.”

As an adult, adverse experiences with PA predominately revolved around hiring a personal trainer and/or engaging in structured exercise classes that were too intense or beyond their skill level. Participant 20 (focus group #2) highlighted this point when stating:

“My negative experience was I had got a personal trainer because I thought everyone said, ‘Get a personal trainer.’ So I went that route. And at the time, I was over 250 pounds at the time. He was a guy. And he was so negative in his approach. Like, ‘Why can’t you do this? Are you too fat?’ He would say those type of comments.”

Participant 23 added (focus group #2):

“I signed up for a free class. It was a Cross-Fit class. And that I walked out of feeling like, damn, that was good…but the next day I felt like I was hit by a truck, and I didn’t go back.”

In reference to the types of PA women enjoyed performing, walking emerged as a preferred activity, as it could be done conveniently, with other friends or family members, and was not as intimidating as other forms of PA. Participant 20 (focus group #2) illustrated this by saying:

“I love to walk. When I walk, it gives me a feeling of excitement. And it just makes me feel good inside.”

Zumba© and other forms of dance were also frequently identified as preferred activities. Less frequently cited activities included swimming, martial arts, strength training, and cycling.

When discussing barriers to PA, commonly reported barriers during the initial phases of discussion included lack of time due to family/caretaking responsibilities and busy work schedules, fatigue or tiredness, hair care, and the extreme heat during the summer months. However, as the focus group dialogue progressed, women began to discuss many of the aforementioned barriers (ie, lack of time, family/caretaking responsibilities, tiredness, extreme heat) as not actual barriers to PA, rather excuses they made for not being active. Individual quotes expressed by participants that highlighted this sentiment include:

“I know for me, I have the time, and I know where I can fit time in to add up to getting things like 10 minutes here and 15 minutes there throughout the day, or even at night. But once I get home, I’m done. I don’t want to do nothing.”

(participant 3, focus group #2)

and

“I do think I have the time. I’m just telling myself I don’t.”

(participant 4, focus group #2)

This evolution among participants was significant, as it emphasizes that many commonly reported barriers to PA among AA women may not be actual barriers, rather excuses or statements of self-preservation.

To overcome many of the barriers to PA noted by participants, women emphasized the need to focus on importance of self-care. Participant 1 (focus group #2) expressed:

“It’s just I think we just all need to be honest with ourselves and realize [unintelligible] priorities in place and bring recreation back as a point of focus for ourselves, as a part of self-care. If we love ourselves, then we’ll do this for ourselves.”

Other strategies proposed by participants included establishing a social support system, identifying PA they can do with their family, and setting achievable goals.

Self-regulation

For this construct, we explored how women could incorporate PA into their daily activities and manage their PA through self-monitoring, goal setting, and self-reward. Women were first asked how they could incorporate more PA into their daily activities. Common responses included walking with their families, parking their vehicles at the farthest parking space away from the entrance of the grocery store or worksite, taking the stairs instead of the elevator, walking to complete daily tasks (ie, checking the mail, grocery shopping), and walking on their lunch break. When prompted to discuss how they could segment their activity into 10-minute bouts throughout the day (coinciding with the national PA guidelines), women described various ways to incorporate walking into their daily schedules. For example, participant 11 (focus group #2) stated:

“I could walk. I have a parking garage. I would walk from the top of the parking garage all the way down to the bottom, and that would take me 10 minutes….and that would be easy, actually.”

Other participants reported they could take a 10-minute break to walk while watching television in the evening and/or walking for 10 minutes at home immediately before and after work. Overall, participants expressed that dividing PA into 3 10-minute bouts was much easier than if the 30 minutes was performed in a single bout.

Throughout the focus groups women expressed that setting aside specific times to be physically active would be an ideal strategy to help establish regular PA habits. Participant 15 (focus group #2) noted:

“I would have to schedule in, because then it becomes a habit. And I’m a person that if I can create that habit, I will be consistent with it.”

Another stated (participant 9; focus group #3):

“It’s not something I do now, but in the past, one of the biggest things was just planning and preparation… if I had a plan in advance, it’s a lot easier to follow through and to stay on top of it.”

Women were also prompted to discuss their previous experiences with tracking or self-monitoring their PA. Most participants reported previous self-monitoring attempts that included journaling, using a pedometer, and using various types of Smart-phone enabled devices (Fitbit©) or applications (ie, My Walk Mac©, My Fitness Pal©). Despite reporting that tracking their PA was a helpful motivational tool, participants reported they ultimately stopped their tracking due to burden or loss of interest. Women generally agreed that the ideal type of self-monitoring device would require minimal effort on their part to record or log their activity.

A final topic discussed among women during focus group sessions was goal setting and rewards/reinforcements for achieving PA goals. Participants emphasized the importance of setting realistic short-term goals to achieve long-term goals. Some women discussed that when long-term goals are too distal, they lose motivation for PA because the results are not immediately ascertained or observable. Similarly, women described the importance of acknowledging small changes in behavior. Participant 8 (focus group #1) illustrated this with the following:

“I feel like, yes, long-term that should be the goal. But I feel like even if you’re starting from zero, just doing something is good. And I think we should feel good about that. I think sometimes all the goals make you feel like the little bit you do isn’t worth it; and you should not do that, because this should be the goal.”

A variety of rewards and reinforcements for achieving PA goals were reported. Monetary (ie, gift cards or cash) and/or tangible products (ie, clothing) were commonly mentioned as favorable rewards among women. However, non-tangible rewards were also discussed, including words of encouragement, praise, and acknowledgment.

Social Support

Social support was as a key factor participants associated with the successful adoption of a physically active lifestyle. Family members emerged as a key source of support, as participants reported that their parents, spouses, siblings, children, and grandchildren as sources of encouragement. Among women who did not have children or family members in close proximity, co-workers and friends were mentioned as potential sources of support. Participant 20 (focus group #3) stated:

“I would have to say my coworkers [are sources of support] because I don’t have any children. I don’t have any family here… Just having other workers to encourage each other; that has helped me.”

Another explained (participant 7, focus group #3):

“I think having a friend who is at your level or maybe somewhere around your level as far as physical activity, that’s definitely an encouragement and you can both hold each other accountable and things like that.”

Interestingly, the majority of participants had a difficult time identifying people who may discourage them from being physically active. Instead, participants reported their own self as a primary source of discouragement (similar to how they described themselves as their own greatest barrier to PA). As participant 19 (focus group #3) noted:

“I don’t necessarily have anyone who’s not supportive, but I know I can be my own worst critic.”

Other participants expressed:

“You know how they say you’re your worst enemy…It’s like you find every excuse in the book not to do it when it’s just go to bridge and get over it and do it.”

(participant 5, focus group #3)

and

“Myself, everybody is supportive for the most part.”

(participant 16, focus group #3)

A final topic explored for this construct was how participants would like to receive social support in the context of a PA program. Participants emphasized that when framing PA promotion messages, a favorable approach would be to recognize participants’ PA efforts and encourage them to continue working hard to achieve their goals. Use of criticism or negatively framed messages was not recommended. Women also identified strategies for how social support could be incorporated into a program. One strategy was to integrate a “partner” or “buddy system” into the program. Participant 21 (focus group #3) stated:

“I think one of the things that I like to hear is I like for somebody maybe to do it with me. If I say maybe I’m going to go walking 2 miles in the morning, it’s nice to hear, “Okay, I’ll get up with you and I’ll go.”

Another strategy discussed by participants to enhance social support was to provide participants with success stories from other AA women. One participated stated (participant 9, focus group #3):

“I think one of the things that is the most helpful for me is when someone shares their struggles, because you look at people and you make the assumption, ‘Okay, they succeeded at it, so it must’ve been fairly easy for them to do,’ rather than being like, ‘I hit hurdles and this is how I overcame them.’”

DISCUSSION

These results highlight the relevance of using the SCT as the theoretical foundation for PA promotion programs for AA women and provide practical guidance on how researchers can leverage the constructs to design a culturally relevant PA program for AA women (Table 2). For the construct of Behavioral Capability, results emphasize the need for women to have a clearly defined behavioral target (ie, the desired dose and intensity of PA). An example would be setting a behavioral target of 150 minutes/week of moderate-intensity PA. Whereas this may seem intuitive, previous reviews have shown that few researchers actually report doing this.18,32 Delineating the behavioral target in a concise manner eliminates ambiguity regarding the desired PA levels of a program. Providing participants with a detailed plan or schedule outlining how they can achieve the recommended PA levels for a program also was advised, a finding that has not been fully elucidated in previous behavioral PA interventions. Another outcome was the need for participants to differentiate between the terms “PA” and “exercise” at the beginning of a PA program. This will provide a solid foundation of knowledge and help reduce any confusion regarding the meaning of these terms throughout a program, while also helping them to consider the PA dose and explore alternative strategies to continue “movement.”

Participants reported a diverse set of outcome expectations associated with being physically active (Table 2), many of which have been reported previously.33–35 Researchers should emphasize as many of these factors as possible throughout implementation of a program, as not all women will be uniformly motivated for PA. For example, a 25-year-old single woman may be more motivated for vanity reasons, whereas a 40-year-old mother of 2 may be more motivated for reduced chronic disease risk and being a positive role model for her children. For the construct of Social Support, women reported a variety of individuals as potential sources of support for PA (ie, spouses, parents, children, and friends). Given that sources of social support will vary among women and likely evolve across the lifespan, PA programs should encourage women to explore potential sources of social support on an ongoing basis. Women also endorsed the need for creating a strong social support infrastructure among the women enrolled in a PA program. This would be particularly advantageous among women who do not have strong social support networks in their personal lives.

An overarching theme that emerged while examining the constructs of Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and Self-Regulation was the difficulty women face balancing work and family responsibilities, while also making time for their own self-care needs. Women reported family and work obligations limited their PA engagement and expressed lacking time altogether for PA or being too tired to perform PA after completing their daily tasks. Our findings align with previous research on this topic36–42 and emphasize the need for programs to design theory-based strategies to address these barriers. Strategies discussed by participants to overcome these issues included setting achievable PA goals, scheduling PA in their daily routines (aligning with the construct of Self-Regulation), and identifying and enacting sources of social support.

It is important to place the context of our findings within the substantial body of research that has examined how the lived experiences and sociocultural norms of AA women influence PA behaviors. Historically, AA women have been viewed as the primary caretakers of their familial units (ie, family and other kinship-type relationships).17 This caretaking role is something many AA women take great pride in, and as a result, can limit their available time to engage in PA.17,24 Previous research indeed shows that some AA women view PA as a self-indulgent or self-serving behavior that takes valuable time away from their family and caretaking responsibilities.43,44 Together, these phenomena have been termed collectively as an AA woman’s “ethic of care” (referring to the self-sacrificing behaviors of AA women to ensure the needs of their familial and community units are met before their own needs).45,46 It is important to note that this phenomenon is prevalent among women of other racial/ethnic backgrounds; however, findings demonstrate it to be more revered and emphasized in the AA community.47,48

Results of our study provide a new perspective on the “ethic of care” of AA women. For example, participants overwhelmingly endorsed the notion that “lack of time” for PA was an excuse, rather than an actual constraint. Moreover, many women: (1) recognized PA as an important part of their self-care; and (2) emphasized that modeling healthy PA behaviors to others was integral to their role as an AA women. Together, these findings suggest that traditional cultural norms associated with PA among AA women may be evolving, and that PA is becoming increasingly recognized as an important health behavior in the AA community (as opposed to just a recreational or leisure activity). Potential strategies to leverage these findings in the design of culturally relevant PA program for AA women include incorporating success stories or testimonials from other AA women to instill a sense of self-worth and self-entitlement for PA (ie, aligning with the emotional arousal and verbal persuasion concepts of Self-Efficacy) and emphasizing how PA is relevant to the various caretaking and community roles of AA women (ie, illustrate the importance of PA as a role modeling behavior to others and highlight how being active on a regular basis can result in increased energy that can help women perform their caretaking tasks and their ability to engage with their children,).17,49

Another interesting finding of our study was that participants reported engaging in various types of PA during childhood and most women viewed these childhood experiences as positive and enjoyable. This outcome is in contrast to some previous qualitative research33,43 that has reported that AA women have had limited exposure to PA during childhood and that PA was discouraged by their parents and/or other family members. Participants’ familiarity with PA and their positive previous experiences may help explain why most women in our study endorsed PA as an important health behavior, providing further support that social norms for PA in the AA community are becoming more favorable. However, future research on this topic is warranted to elucidate our findings further.

Lastly, we would be remiss not to acknowledge that some of our results transcend racial/ethnic backgrounds and are likely relevant to all women (and some men), regardless of race/ethnicity. For example, clearly defining PA and exercise at the onset of an intervention and delineating the behavioral target of an intervention is a best practice for all PA programs. Likewise, many of the barriers (ie, issues with work-life balance, lack of energy for PA), sources of social support (ie, family, friends, other participants in a PA intervention), and self-regulation strategies for PA (ie, scheduling PA into daily activities, ways to incorporate 10-minutes bout of activity into the day) reported by participants will resonate among women of all racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Limitations of the study include the sample being comprised of predominately highly educated women residing in a single southwestern US metropolitan city. Findings may have limited transferability to AA women in other regions of the US, those in more urban or rural areas, or women with lower education levels. We also acknowledge that having the PI, a white male, facilitate one of the focus groups may have influenced the level of disclosure among study participants. However, given that the PI had established a relationship with participants during the recruiting, screening, and scheduling process and is a known health advocate in the AA community, we believe this bias to be minimal. Moreover, qualitative data collected during this focus group were comparable to data provided in the other groups examining the same topics, which further attenuated this concern. Another potential limitation was that composition of participants attending individual focus group sessions differed as participants progressed through the series of 3 focus groups (ie, participants were not required to attend all focus groups with the same group of women they attended for focus group #1). This change in group composition may have influenced group dynamics, and could have influenced study findings. However, we contend this issue is no different than studies that have participants attend a single focus group session to examine a phenomenon of interest (which is a common study design in the social sciences), and that the use of a trained facilitator helped mitigate any influences this may have had on the results.

Despite these limitations, the primary strength of the current study is that it is one of few studies to explore how the constructs of the SCT define the problem of insufficient PA levels, and how SCT can be leveraged in the design of culturally relevant PA programs for AA women. The empirically derived data specified the problem of insufficient PA and helped refine the problem in terms of “meaning, manifestations, determinants, and consequences”9 to elucidate intervention design and strategies.

Effective behavioral interventions to increase PA among AA women require an in-depth understanding of the factors associated with PA engagement, prevalent barriers to PA, and how behavioral theory can be leveraged to acknowledge and overcome these norms and barriers. This study addressed all 3 of these factors by exploring how constructs of the SCT can be optimized in the design of culturally relevant PA program. Findings emphasize the relevance of the SCT in the design of PA programs for AA women and illustrate how researchers can translate behavioral constructs into practice when designing PA programs for AA women.

Figure 3.

Focus Group Guide Used in the Focus Group #2 Sessions

Acknowledgments

We thank all study participants for the contributions to the study. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH/NHLBI), award K99 HL129012 (R. Joseph, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NHLBI.

Contributor Information

Rodney P. Joseph, College of Nursing and Health Innovation, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ.

Barbara E. Ainsworth, Exercise Science and Health Promotion Program, School of Nutrition and Health Promotion, College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ.

LaTanya Mathis, Community member of the metropolitan Phoenix area, Phoenix, AZ.

Steven P. Hooker, Exercise Science and Health Promotion Program, School of Nutrition and Health Promotion, College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ.Colleen Keller.

Colleen Keller, College of Nursing and Health Innovation, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ.

References

- 1.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed August 1, 2015];Health Data Interactive. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hdi/index.htm.

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States. JAMA. 2014;312:189–190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed May 19, 2016];Age-adjusted rates of diagnosed diabets per 100 civilian, non-institutionalized population, by Hispanic origin and sex, United States, 1997–2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/prev/national/fighispanicthsex.htm.

- 5.Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy RL, Finch EA, Crowell MD, et al. Behavioral intervention for the treatment of obesity: strategies and effectiveness data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2314–2321. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies CA, Spence JC, Vandelanotte C, et al. Meta-analysis of internet-delivered interventions to increase physical activity levels. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidani SB, Braden CJ. Design, Evaluation, and Translation of Nursing Interventions. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus BH, Williams DM, Dubbert PM, et al. Physical activity intervention studies: what we know and what we need to know: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Subcommittee on Physical Activity); Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; and the Interdisciplinary Working Group on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Circulation. 2006;114:2739–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph RP, Durant NH, Benitez TB, Pekmezi DW. Internet-based physical activity interventions. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2013;8:42–68. doi: 10.1177/1559827613498059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph RP, Daniel CL, Thind H, et al. Applying psychological theories to promote long-term maintenance of health behaviors. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10(6):356–368. doi: 10.1177/1559827614554594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Framework. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, et al. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28:690–701. doi: 10.1037/a0016136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chase JA. Physical activity interventions among older adults: a literature review. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2013;27(1):53–80. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.27.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bélanger-Gravel A, Godin G, Vézina-Im LA, et al. The effect of theory-based interventions on physical activity participation among overweight/obese individuals: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12(6):430–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joseph RP, Keller C, Affuso O, Ainsworth BE. Designing culturally relevant physical activity programs for African-American women: a framework for intervention development. J Racial Ethn Health Dispar. 2017;4(3):397–409. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0240-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitt-Glover MC, Keith NR, Ceaser TG, et al. A systematic review of physical activity interventions among African American adults: evidence from 2009 to 2013. Obes Rev. 2014;15(Suppl 4):125–145. doi: 10.1111/obr.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML, Schiffer L, et al. Obesity reduction black intervention trial (ORBIT): six-month results. Obesity. 2009;17(1):100–106. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bopp M, Wilcox S, Laken M, et al. 8 Steps to Fitness: a faith-based, behavior change physical activity intervention for African Americans. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(5):568–577. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.5.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Migneault JP, Dedier JJ, Wright JA, et al. A culturally adapted telecommunication system to improve physical activity, diet quality, and medication adherence among hypertensive African-Americans: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(1):62–73. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9319-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parra-Medina D, Wilcox S, Salinas J, et al. Results of the Heart Healthy and Ethnically Relevant Lifestyle trial: a cardiovascular risk reduction intervention for African American women attending community health centers. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1914–1921. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liamputtong P. Focus Group Methodology: Principles and Practice. London, UK: SAGE; 2016. pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joseph RP, Ainsworth BE, Keller C, Dodgson JE. Barriers to physical activity among African American women: an integrative review of the literature. Women Health. 2015;55(6):679–699. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2015.1039184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph RP, Pekmezi D, Allison JJ, Durant NH. Lessons learned from the development and implementation two Internet-enhanced culturally relevant physical activity interventions for young overweight African American women. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2014;25(1):42–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joseph RP, Keller C, Adams MA, Ainsworth BE. Print versus a culturally-relevant facebook and text message delivered intervention to promote physical activity in African American Women: a randomized pilot trial. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:30. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joseph RP, Pekmezi D, Dutton GR, et al. Results of a culturally adapted internet-enhanced physical activity pilot intervention for overweight and obese young adult African American women. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(2):136–146. doi: 10.1177/1043659614539176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph RP, Pekmezi DW, Lewis T, et al. Physical activity and social cognitive theory outcomes of an Internet-enhanced physical activity intervention for African American female college students. [Accessed June 6, 2017];J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2013 6(2):1–8. Available at: http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/departments/pediatrics/subs/can/research/pubs/Documents/2013%20Physical%20activity%20and%20social%20cognitive%20theory.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph RP, Keller C, Adams MA, Ainsworth BE. Validity of two brief physical activity questionnaires with accelerometers among African-American women. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2016;17(3):265–276. doi: 10.1017/S1463423615000390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitt-Glover MC, Kumanyika SK. Systematic review of interventions to increase physical activity and physical fitness in African-Americans. Am J Health Promot. 2009;23(6):S33–S56. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.070924101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilcox S, Oberrecht L, Bopp M, et al. A qualitative study of exercise in older African American and white women in rural South Carolina: perceptions, barriers, and motivations. J Women Aging. 2005;17(1–2):37–53. doi: 10.1300/J074v17n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilcox S, Richter DL, Henderson KA, et al. Perceptions of physical activity and personal barriers and enablers in African-American women. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(3):353–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson KA, Ainsworth BE. A synthesis of perceptions about physical activity among older African American and American Indian women. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):313–317. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bopp M, Lattimore D, Wilcox S, et al. Understanding physical activity participation in members of an African American church: a qualitative study. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(6):815–826. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richter DL, Wilcox S, Greaney ML, et al. Environmental, policy, and cultural factors related to physical activity in African American women. Women Health. 2002;36(2):91–109. doi: 10.1300/j013v36n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walcott-McQuigg JA, Zerwic JJ, Dan A, Kelley MA. An ecological approach to physical activity in African American women. Medscape Womens Health. 2001;6(6):3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pekmezi D, Marcus B, Meneses K, et al. Developing an intervention to address physical activity barriers for African-American women in the deep south (USA) Womens Health. 2013;9(3):301–312. doi: 10.2217/whe.13.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eyler AA, Baker E, Cromer L, et al. Physical activity and minority women: a qualitative study. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(5):640–652. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoebeke R. Low-income women’s perceived barriers to physical activity: focus group results. Appl Nurs Res. 2008;21(2):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ingram D, Wilbur J, McDevitt J, Buchholz S. Women’s walking program for African American women: expectations and recommendations from participants as experts. Women Health. 2011;51(6):566–582. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.606357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Im EO, Ko Y, Hwang H, et al. “Physical activity as a luxury”: African American women’s attitudes toward physical activity. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(3):317–339. doi: 10.1177/0193945911400637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harley AE, Odoms-Young A, Beard B, et al. African American social and cultural contexts and physical activity: strategies for navigating challenges to participation. Women Health. 2009;49(1):84–100. doi: 10.1080/03630240802690861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilligan C. In a Different Voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henderson K, Allen K. The ethic of care: leisure possibilities and constraints for women. Soc Leisure. 1991;14:97–113. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eyler AA, Matson-Koffman D, Vest JR, et al. Environmental, policy, and cultural factors related to physical activity in a diverse sample of women: the Women’s Cardiovascular Health Network Project – summary and discussion. Women Health. 2002;36(2):123–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones LV, Hopson LM, Gomes A-M. Intervening with African-Americans: culturally specific practice considerations. J Ethn And Cult Divers in Soc Work. 2012;21(1):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gans KM, Kumanyika SK, Lovell HJ, et al. The development of SisterTalk: a cable TV-delivered weight control program for black women. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 1):654–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]