Abstract

Imprecise terminology obscures the reasons why a cancer patient might be willing to endure the potential toxicities and side‐effects of treatment. Renaming of the categories of chemotherapy is proposed here to clarify intended definitions.

Although chemotherapy is commonly categorized as being either curative or palliative, these terms no longer fully reflect chemotherapy's intended uses. This imprecise terminology obscures the reasons why a cancer patient might be willing to endure the potential toxicities and side effects of treatment as a means to a desired end. To clarify the intended use, we propose renaming the categories of chemotherapy so that each descriptor more accurately reflects its expected outcomes and contemporary goals of care.

Curative Chemotherapy

Curative chemotherapy is chemotherapy administered with the goal of achieving a complete remission and preventing the recurrence of cancer. In the case of newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma, testicular cancer, and acute lymphocytic leukemia, the term curative chemotherapy accurately reflects the expected outcome, that is, cure, and the reason for its utilization. This characterization also encompasses chemotherapy's use as adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery for localized breast cancer, colorectal cancer, or lung cancer. Use of the term curative chemotherapy thus appears unproblematic.

Palliative Chemotherapy

By contrast, oncologists typically use the term palliative chemotherapy to refer to any chemotherapy administration that is not curative [1]. Consequently, the term is defined by what it is not, that is, curative, rather than specifying the intended palliation. Wikipedia explains plainly that: “Salvage chemotherapy or palliative chemotherapy is given without curative intent, but simply to decrease tumor load and increase life expectancy.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/chemotherapy#cite‐note‐isbn0‐470‐09254‐8‐2) Others have defined palliative chemotherapy as “…treatment in circumstances where the impact of intervention is insufficient to result in major survival advantage, but does affect improvement in terms of tumor‐related symptoms…” [2]. Use of both palliative chemotherapy and salvage chemotherapy thus appears problematic.

Salvage Chemotherapy

Salvage chemotherapy was, long ago, first understood to be a form of curative chemotherapy, particularly for hematologic malignancies, as when patients have not responded to, or progressed on, first‐line curative therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma [3], [4]. However, its current usage is ambiguous since it has also been used as a synonym for palliative chemotherapy, as in the definition in the prior paragraph above in Wikipedia. Further, its current usage, even for curative salvage, has generally been supplanted by other terminology, specifically by reference to the lines of therapy, that is, second‐line or third‐line therapy for patients who have progressed on first‐line curative chemotherapy. We, therefore, recommend that oncologists avoid using this term.

Palliative chemotherapy was first mentioned in the 1950s accompanying the first use of cytotoxic chemotherapy [5]. By the early to mid‐1960s, the practical application of palliative chemotherapy for solid tumors became routine [6], [7], [8], [9]. In those days, the term “palliative” was indeed focused on the reduction of pain and symptoms. There may have been a concomitant increase in survival, but in most cases this was relatively rare. Five decades later, the oncologist's armamentarium is broader and, in many settings, patient outcomes have improved dramatically. Oncologists, nevertheless, still dichotomize chemotherapy into “curative” and “palliative” even though these terms frequently do not fit with the present goals of care.

We object to the current usage of the term palliative chemotherapy because we do not believe that the intended outcome is palliation. The recognition of palliative medicine as a medical specialty has altered the meaning of the term “palliative” for patients and providers. The word has come to have a negative connotation, implying that the patient is near the end‐of‐life, thus equating “palliative chemotherapy” with “end‐of‐life chemotherapy.” We see two problems with use of the term palliative chemotherapy: (a) it may unnecessarily alarm patients who are not near death and (b) its use for patients who truly are at the end‐of‐life is misapplied because it is not necessarily prescribed for the purposes of palliation.

Life‐Extending Chemotherapy

The term palliative chemotherapy might have been appropriate in the era when life expectancy for most cancers numbered a few months, even with chemotherapy. But fortunately, outcomes have improved, in some cases dramatically. For many metastatic tumors, even if incurable, survival with chemotherapy and best treatment is now well over a year and frequently much more. Colorectal cancer survival often exceeds 24 months with 10% of patients surviving more than five years [10], [11]. Breast and prostate cancer patients with metastatic disease also survive years, frequently past 10 years. If chemotherapy is offered with the goal of prolonging life, but not preventing recurrence, that is, not curative, we would suggest, instead, the use of the term life‐extending chemotherapy.

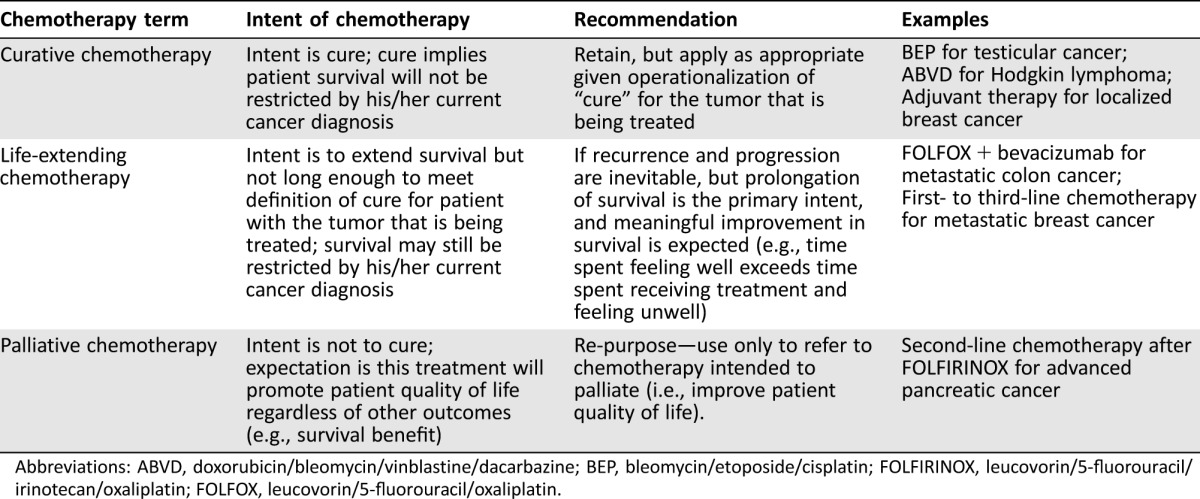

Given the growing disconnect between names and expected outcomes with chemotherapy, we recommend a renaming such that the terms curative, life‐extending, and palliative chemotherapy correspond to the current outcomes expected to result from the administration of chemotherapy (Table 1). In our redefined nomenclature, curative chemotherapy retains its meaning as chemotherapy given with a high likelihood of improving a patient's probability of non‐recurrence. Life‐extending chemotherapy then refers to chemotherapy whose primary intent is to extend a patient's life for a meaningful length of time. The real challenge will then be to determine in each case what constitutes “meaningfully” enhanced survival. We recognize that every administration of chemotherapy may have this as its goal, but this would require evidence that the chemotherapy prescribed would provide the expected outcome in terms of “extra” life worth living. For example, if a patient were given chemotherapy to live long enough to witness the birth of a grandchild, rather than to palliate symptoms, we recommend it be called life‐extending chemotherapy. As we increasingly evaluate the value of chemotherapy, this will become easier.

Table 1. Chemotherapy terms, intent, and recommendations.

Abbreviations: ABVD, doxorubicin/bleomycin/vinblastine/dacarbazine; BEP, bleomycin/etoposide/cisplatin; FOLFIRINOX, leucovorin/5‐fluorouracil/irinotecan/oxaliplatin; FOLFOX, leucovorin/5‐fluorouracil/oxaliplatin.

Finally, palliative chemotherapy could resume its meaning as it had when it began—the use of chemotherapy for the primary purpose of palliating symptoms. Whether there are many circumstances where this can be justified anymore is a matter of debate and further discussion. The American Society of Clinical Oncology has issued guidelines discouraging such usage [12]. Our own study demonstrated that the use of chemotherapy in settings where there is no evidence to establish its benefit in prolonging survival often leads to a worse quality of life rather than to palliation [13].

Our nomenclature would clarify the intent of the chemotherapy to the patient (and family members and health care providers), provide an accurate and less demoralizing language for patients and, by reducing confusion as to the intent of treatment, promote informed decision‐making. In many instances, outcomes produced by chemotherapy have improved dramatically. The time has come for the terms used to describe chemotherapy to reflect the current goals of this type of care more accurately.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Prigerson is supported by National Cancer Institute grant CA197730.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Virginia G. Kaklamani. Clinical Implications of the Progression‐Free Survival Endpoint for Treatment of Hormone Receptor‐Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. The Oncologist 2016;21:922–930.

Implications for Practice: Advances in drug development during the past two decades have provided numerous options for treatment of advanced breast cancer that include monotherapy with endocrine modulating agents and dual therapy that combines endocrine therapy with an inhibitor targeting the mammalian target of rapamycin serine‐threonine kinase or cyclin‐dependent kinase pathways known to be involved with resistance. Clinical trial endpoints for breast cancer have evolved as well. Communication of progression‐free survival, overall survival, and other outcomes with patients should incorporate the context of the individual's treatment plan and include discussion of response rate, side effects, and quality of life.

Disclosures

Alfred I. Neugut: Pfizer, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, United BioSource Corporation (C/A), Executive Health Exams International (SAB). The other author indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1. Browner I, Carducci MA. Palliative chemotherapy: Historical perspective, applications, and controversies. Semin Oncol 2005;32:145.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Archer VR, Billingham LJ, Cullen MH. Palliative chemotherapy: No longer a contradiction in terms. The Oncologist. 1999;4:470.–. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clamon GH, Corder MP. ABVD treatment of MOPP failures in Hodgkin's disease: A re‐examination of goals of salvage therapy. Cancer Treat Rep 1978;62:363.–. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Portlock CS, Rosenberg SA, Glatstein E et al. Impact of salvage treatment on initial relapses in patients with Hodgkin disease, stages I‐III. Blood 1978;51:825.–. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morel A, Josserand A, Detry R. [Perfection of a method of palliative chemotherapy of certain epithelial cancers]. Lyon Med 1950;183:3.–. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hart GD. Palliative Management of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Can Med Assoc J 1964;90:1265.–. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Palm ET. Palliation in Metastatic Carcinoma of the Breast. Minn Med 1964;47:179.–. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mrazek RG, Economou SG. Palliative chemotherapy of solid tumors with nitromin. AMA Arch Surg 1959;78:51.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilson ND. Palliation of advanced cancer by chemotherapy. West J Surg Obstet Gynecol 1963;71:45.–. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Renouf DJ, Lim HJ, Speers C et al. Survival for metastatic colorectal cancer in the bevacizumab era: a population‐based analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2011;10(2):97.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jawed I, Wilkerson J, Prasad V et al. Colorectal Cancer Survival Gains and Novel Treatment Regimens: A Systematic Review and Analysis. JAMA Oncol 2015;1(6):787.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schnipper LE, Smith TJ, Raghavan D et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology identifies five key opportunities to improve care and reduce costs: The top five list for oncology. J Clin Oncol 10 2012;30:1715.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA et al. Chemotherapy Use, Performance Status, and Quality of Life at the End of Life. JAMA Oncol 2015;1:778.–. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]