Abstract

Objective

Our objective was to analyze factors predicting outcomes after a total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation (TP-IAT).

Background

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is increasingly treated by a TP-IAT. Postoperative outcomes are generally favorable, but a minority of patients fare poorly.

Methods

In our single-centered study, we analyzed the records of 581 patients with CP who underwent a TP-IAT. Endpoints included persistent postoperative “pancreatic pain” similar to preoperative levels, narcotic use for any reason, and islet graft failure at 1 year.

Results

In our patients, the duration (mean ± SD) of CP before their TP-IAT was 7.1 ±0.3 years and narcotic usage of 3.3 ± 0.2 years. Pediatric patients had better postoperative outcomes. Among adult patients, the odds of narcotic use at 1 year were increased by previous endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and stent placement, and a high number of previous stents (>3). Independent risk factors for pancreatic pain at 1 year were pancreas divisum, previous body mass index >30, and a high number of previous stents (>3). The strongest independent risk factor for islet graft failure was a low islet yield—in islet equivalents (IEQ)—per kilogram of body weight. We noted a strong dose-response relationship between the lowest-yield category (<2000 IEQ) and the highest (≥5000 IEQ or more). Islet graft failure was 25-fold more likely in the lowest-yield category.

Conclusions

This article represents the largest study of factors predicting outcomes after a TP-IAT. Preoperatively, the patient subgroups we identified warrant further attention.

Keywords: chronic pancreatitis, total pancreatectomy, islet autotransplantation

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a disorder that is challenging to patients and physicians alike. Its incidence is estimated at 0.2% to 0.6% in the United States.1,2 The economic impact of the disease is notable with total estimated annual health care expenditures of $2.6 billion.3

The initial treatment of CP is directed towards relieving pain and restoring quality of life. Interventions are aimed at correcting the inciting mechanical, metabolic, immunologic, or pharmacologic events, with the use of options such as narcotic analgesics, pancreatic enzymes (to reduce pancreatic stimulation and treat pancreatic exocrine insufficiency), and, occasionally, nerve block procedures.4,5 If these medical and endoscopic interventions fail, patients may be candidates for surgery.

Surgical techniques include partial pancreatic resection and drainage procedures such as lateral pancreaticojejunostomy or variants. Patients often have transient pain relief, but given the diffuse nature of CP and the involvement of the entire pancreas, pain eventually recurs in up to 50% patients,6,7 in addition, exocrine and endocrine insufficiency often develops, over time.8

A total pancreatectomy (TP) completely removes the root cause of pain. However, a TP alone, in the absence of preservation of any beta-cell function, results in diabetes that is often difficult to manage, similar to type 1 diabetes mellitus but with the added problem of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Thus, a combination procedure—that is, a TP along with an intraportal islet autotransplant (TP-IAT)—was designed to preserve beta-cell mass and insulin secretory capacity as much as possible and to mitigate diabetic complications. Most CP patients are not diabetic when they first seek treatment for their intractable pain, and thus have some degree of beta-cell mass worth preserving (even though, eventually, CP typically results in diabetes by progressively destroying islets).

The world’s first TP-IAT was performed at the University of Minnesota in 1977 to treat a patient with painful CP.9 Since then, nearly 600 TP-IATs have been performed in adults and children. We previously reported the Minnesota series with an emphasis on the efficacy of TP-IATs in terms of islet function, pain relief, narcotic use, and quality of life.10–12 Postoperative outcomes are generally favorable but a substantial minority of patients fare poorly. Over time, we have attempted to standardize our approach, yet we still have very limited data on factors predicting outcomes after a TP-IAT. In this study, our objective was to analyze factors predicting outcomes, particularly poor outcomes, after a TP-IAT with an ultimate goal of improving the patient selection process.

METHODS

From February 14, 1977, through November 3, 2014, we performed a total of 581 TP-IATs at our center. Of these procedures, 490 were in adults and 91 in children. Over the years, our patient selection criteria have evolved; as of 2008, we standardized them (Table 1).10 For each patient who consented to surgery, the decision to proceed with a TP-IAT was made by a multidisciplinary team consisting of adult and pediatric gastroenterologists, surgeons, endocrinologists, a pain specialist, a health psychologist, dieticians, and nurse coordinators who met weekly. If any member of that team objected or had any reservations, the TP-IAT was delayed or canceled until relevant issues were addressed. The current study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. Informed consent and assent were obtained from parents and patients for all patients participating in quality of life assessments.

TABLE 1.

Criteria for a TP-IAT, University of Minnesota

| Definitions |

| Chronic pancreatitis (CP) |

Chronic abdominal pain, lasting more than 6 months; features consistent with CP; and evidence of CP by at least 1 of the following:

|

| OR |

Relapsing acute pancreatitis (relapsing AP)

|

| OR |

| Documented hereditary pancreatitis with compatible clinical history |

Indications for a TP-IAT (Must have all of below)

|

Contraindications for a TP-IAT

|

Surgical Technique

Our surgical technique that has evolved continuously over our study interval has been described elsewhere.10,11 TP is performed in such a way that the blood supply to the pancreas is preserved until just before its removal, thus minimizing warm ischemia time and maximizing islet preservation. In the early part of our TP-IAT series, we restored gastrointestinal continuity by anastomosing the first portion of the duodenum to the fourth portion of the duodenum and then performing a choledochoduodenostomy to the first part of duodenum. Because of a significant number of patients with bile reflux gastritis and ascending cholangitis, we modified the typical resection to preserve the pylorus, to resect most of the duodenum with the pancreas, and to create a Roux-en-Y biliary drainage entering the enteric stream 40 cm distal to a duodenojejunostomy. We routinely placed a gastrojejunostomy feeding tube in the stomach, using the Stamm technique, with the tip of the jejunal limb placed in the jejunum. In addition, in all patients, we performed a cholecystectomy and, if not previously done, an appendectomy.

Islet Isolation

The basic method of islet isolation remained the same throughout our study period.13

Several enzyme preparations have been used throughout the years.14,15 Most recently, the enzyme mixture has consisted of intact C1 collagenase (VitaCyte, Indianapolis, IN) and neutral protease (SERVA, Heidelberg, Germany), both produced by Clostridium histolyticum. The final islet tissue preparation was suspended in 200 mL CMRL culture medium (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) per infusion bag, with human serum albumin added to a final concentration of 2.5%, HEPES at 25 mM, and ciprofloxacin at 20 μg/mL. Since 2011, we added heparin at 35 U/kg to the final islet preparation to protect against aggregation before infusion. We permitted a maximum of 10 cc of settled tissue per infusion bag. The total islet isolation and preparation time ranged from 3.5 to 6.5 hours (median, 4.5 hours).

Postoperative Care

In most of our patients, immediate extubation was possible. Our routine use of dexmedetomidine infusion and paravertebral nerve blocks augmented early postoperative pain control and minimized narcotic analgesia. During the first 3 postoperative months, use of exogenous insulin was nearly universal in our TP-IAT patients to maintain euglycemia and reduce beta-cell functional stress during the engraftment (neovascularization) stage.16 Patients were seen postoperatively in outpatient clinics at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and then annually. To assess metabolic control and islet graft function, we obtained routine laboratory studies at these intervals—fasting glucose and C-peptide, stimulated glucose and C-peptide, and hemoglobin A1c level. Beginning in 2006, we administered quality of life surveys to patients undergoing TP-IAT (n = 112).17

Data Analysis

For the 581 TP-IATs performed at our center from February 14, 1977, through November 3, 2014, we reviewed the patients’ medical records and clinical data prospectively stored in a long-term database. Summary measures were expressed as a percent of counts or as the mean and accompanying standard error of the mean (SEM). To test for differences in measures, we used a Pearson χ2 test or an independent sample t test.

The number of pediatric patients in our entire retrospective cohort was insufficient for multivariate analysis, so we limited our multivariate models to adults with at least 1 year of follow-up. Endpoints at 1 year included (1) narcotic use for any reason; (2) persistent postoperative pancreatic pain’ similar to preoperative levels; (3) insulin dependence (ie, daily use of multiple doses of insulin or C-peptide <0.5 ng/mL); and (4) any deficit in physical or mental health of the patient and their response on the SF-36 regarding health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Specifically, for HRQoL, we calculated each patient’s physical component summary (PCS) score and mental component summary (MCS) score according to their responses before surgery and at 1 year.18,19 Such aggregate scores have been normalized to the US population to a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. For our study, we treated any value less than 50 for either the PCS or the MCS score as a deficit in physical and mental health. We looked at risk factors for impaired HRQoL at only 2 intervals—before surgery and then at 1 year.

Each outcome was expressed as the cumulative incidence at 1 year.20 For each outcome, we created multivariable logistic regression models.20 First, we examined the bivariate association between each risk factor and the outcome. Then, we included unadjusted risk factors that were significantly associated with the outcome (P <0.100) in forward and backward stepwise regression methods to arrive at the final model.

Results are expressed as unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with accompanying 95% confidence intervals and P values. The discrimination of the multivariable model is expressed as the area under the curve (AUC); to test calibration, we used the Hosmer–Lemeshow chisquare statistic.21 For all analysis, we used SAS/STAT version 9.3 of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Our study group of 581 patients included 490 adults and 91 children (Table 2). Nearly three-fourths (74.9%) of the adults, versus slightly over half (54.9%) of the pediatric patients were female (P < 0.001). Since 2006, the overall volume of transplants increased markedly; over 80% of the pediatric transplants were done in the past 4 years (P = 0.028). Adults and pediatric patients differed in terms of the primary cause of CP: idiopathic in nearly half (48.8%) of the adults versus genetic or hereditary in most (68.1%) of the pediatric patients (P < 0.001).

TABLE 2.

Patient Characteristics of Adult and Pediatric Patients Receiving TP-IAT

| Mean % or Mean ± SEM | Adult (n = 490) | Pediatric (n = 91) | Total (n = 581) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, years | NA | |||

| 3 to 12 | – | 42 (46.2%) | 42 (8.6%) | |

| 13 to 17 | – | 49 (53.8%) | 49 (10.0%) | |

| 18 to 29 | 112 (22.9%) | – | 112 (22.9%) | |

| 30 to 39 | 140 (28.6%) | – | 140 (28.6%) | |

| 40 to 49 | 148 (30.2%) | – | 148 (30.2%) | |

| 50 to 72 | 90 (18.4%) | – | 90 (18.4%) | |

| Female sex | 367 (74.9%) | 50 (54.9%) | 417 (71.8%) | <0.001 |

| Transplant era | 0.028 | |||

| Before 1996 | 48 (9.8%) | 1 (1.1%) | 49 (8.4%) | |

| 1996 to 2005 | 93 (19.0%) | 17 (18.7%) | 110 (18.9%) | |

| 2006 to 2013 | 349 (71.2%) | 73 (80.2%) | 422 (72.6%) | |

| Pretransplant diabetes | 38 (7.8%) | 3 (3.3%) | 41 | 0.127 |

| Cause of chronic pancreatitis | ||||

| Alcohol | 31 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 31 (5.3%) | <0.001 |

| Idiopathic | 239 (48.8%) | 18 (19.8%) | 257 (44.2%) | |

| Pancreas divisum | 90 (18.4%) | 3 (3.3%) | 93 (16.0%) | |

| Genetic or hereditary | 66 (13.5%) | 62 (68.1%) | 128 (22.0%) | |

| Other | 64 (13.1%) | 8 (8.8%) | 72 (12.4%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | NA | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 48 (10.3%) | – | – | |

| Normal (18.5 to 24.9) | 223 (47.8%) | – | – | |

| Overweight (25.0 to 29.9) | 111 (23.8%) | – | – | |

| Obese (≥30) | 85 (18.2%) | – | – | |

| IEQ per kg body weight | 0.033 | |||

| <2,000 | 89 (23.0%) | 23 (25.3%) | 112 (23.4%) | |

| 2000 to 2999 | 68 (17.6%) | 12 (13.2%) | 80 (16.7%) | |

| 3000 to 3999 | 75 (19.4%) | 8 (8.8%) | 83 (17.4%) | |

| 4000 to 4999 | 47 (12.1%) | 10 (11.0%) | 57 (11.9%) | |

| ≥5000 | 108 (27.9%) | 38 (41.8%) | 146 (30.5%) | |

| Previous surgery | ||||

| Puestow | 36 (7.4%) | 11 (12.1%) | 47 (8.1%) | 0.129 |

| Beger or frey | 6 (1.2%) | 3 (3.3%) | 9 (1.5%) | 0.142 |

| Whipple | 28 (5.7%) | 1 (1.1%) | 29 (5.0%) | 0.063 |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 23 (4.7%) | 6 (6.6%) | 29 (5.0%) | 0.445 |

| Number of previous stents | 0.036 | |||

| None | 208 (42.9%) | 51 (56.7%) | 259 (45.0%) | |

| 1 | 156 (32.2%) | 16 (17.8%) | 172 (29.9%) | |

| 2 | 41 (8.5%) | 7 (7.8%) | 48 (8.3%) | |

| ≥3 | 80 (16.5%) | 16 (17.8%) | 96 (16.7%) | |

| Years with pancreatitis | 7.1 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Years of narcotic use | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 0.005 |

IEQ indicates islet equivalents; NA, not applicable or not available; SEM, standard error of the mean.

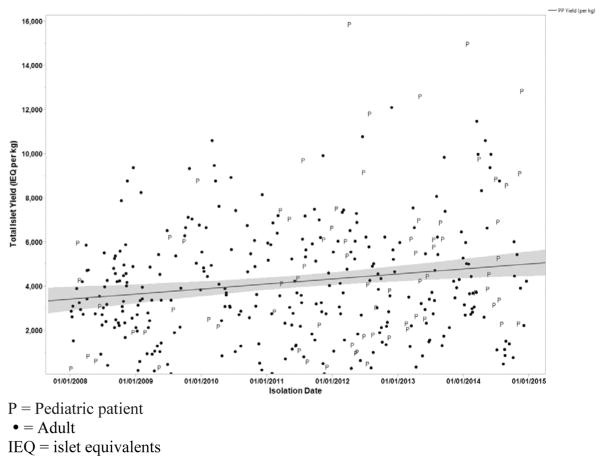

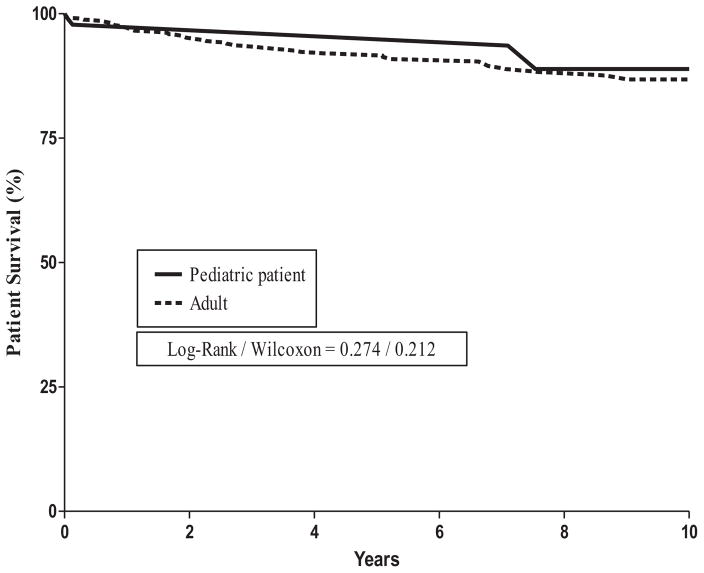

Islet yields were higher in pediatric patients than in adults (P = 0.033). Adults were more likely to have undergone previous procedures, including endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and surgery. Of the total of 581 patients, 151 (26%) had undergone previous surgical procedures that failed. The duration of narcotic use was longer in adults than in pediatric patients (P = 0.005); so was the duration of either acute pancreatitis or CP (P < 0.001). During the entire study period of 37 years, 48 patients died (44 adults and 4 pediatric patients). There were 4 inhospital deaths within 30 days (pulmonary embolism = 1, colon perforation = 1, multisystem organ failure = 1, disseminated intravascular coagulation = 1).

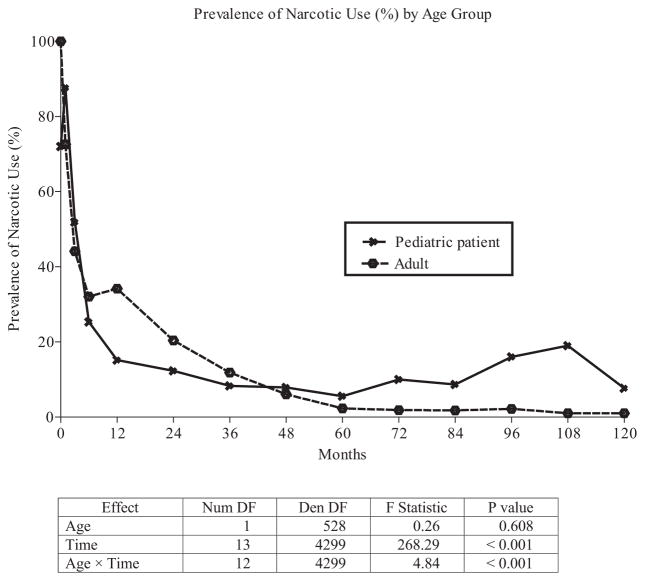

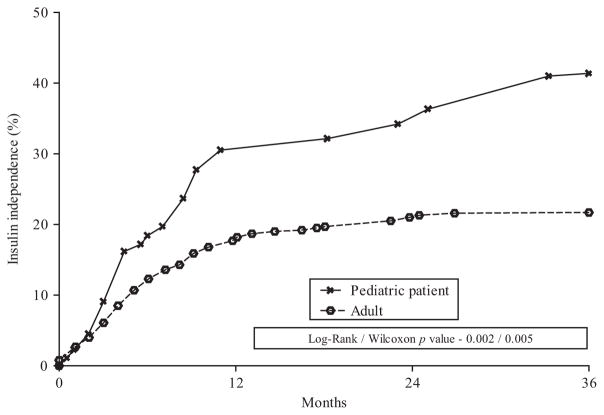

Pediatric patients had higher insulin independence (P = 0.002), lower islet graft failure at 1 year (P = 0.001), and lower cumulative incidence of persistent pancreatic pain at 1 year (2% vs 7.5%) compared to adults. We found no significant differences in narcotic use between adults and pediatric patients at 1 year (P = 0.608), although the prevalence of narcotic use dropped more rapidly in pediatric patients than in adults.

Predictors of Narcotic Use

For our clinical outcome analysis of the association between potential risk factors and narcotic use, we assessed 452 adult TP-IAT patients who completed at least 1 year of follow-up (Table 3). Information on narcotic use at 1 year was missing for 16 patients.

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios Risk Factors Associated With Narcotic Use at 1 Year After TP-IAT

| Unadjusted

|

Multivariate Adjusted

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Cumulative incidence of narcotic use | 34% | |||

| Age group, years | ||||

| 18–29 | 1.00 | |||

| 30–39 | 0.93 (0.59–1.44) | 0.732 | ||

| 40–49 | 0.93 (0.60–1.44) | 0.734 | ||

| 50–72 | 0.97 (0.58–1.63) | 0.905 | ||

| Female sex | 0.82 (0.52–1.31) | 0.413 | ||

| Pretransplant diabetes | 0.95 (0.46–1.95) | 0.887 | ||

| Causes of chronic pancreatitis | ||||

| Alcoholism | 0.85 (0.43–1.68) | 0.634 | ||

| Idiopathic | 1.35 (0.88–2.06) | 0.165 | ||

| Pancreas divisum | 1.92 (1.20–3.08) | 0.007 | ||

| Genetic or hereditary | 0.58 (0.31–1.07) | 0.079 | ||

| Other | 1.00 | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 1.06 (0.54–2.06) | 0.866 | ||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 1.00 | |||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 1.27 (0.80–2.03) | 0.313 | ||

| Obese (≥30) | 1.06 (0.62–1.80) | 0.831 | ||

| Previous surgery | ||||

| Puestow | 0.18 (0.05–0.58) | 0.002 | 0.19 (0.05–0.66) | 0.009 |

| Beger or frey | 1.95 (0.39–9.76) | 0.411 | ||

| Whipple | 1.18 (0.5 to, 2.65) | 0.687 | ||

| Distal pancreatectomy | 0.19 (0.04–0.81) | 0.013 | ||

| Previous stent | 4.68 (2.85–7.67) | <0.001 | 1.93 (0.99–3.77) | 0.055 |

| Number of previous stents | ||||

| None | 1.00 | |||

| 1 | 1.54 (1.02–2.33) | 0.038 | ||

| 2 | 1.63 (0.85–3.13) | 0.138 | ||

| ≥3 | 2.95 (1.79–4.85) | <0.001 | 2.73 (1.10–6.79) | 0.020 |

| Any spincterotomy | 8.44 (3.58–19.89) | <0.001 | 1.76 (1.09–2.83) | 0.020 |

| Years with pancreatitis | ||||

| <5 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥5 | 0.73 (0.49–1.09) | 0.152 | ||

| Years of narcotic use | ||||

| <5 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥5 | 1.27 (0.74–2.18) | 0.037 | ||

|

| ||||

| Areas under the curve Hosmer-Lemeshow | 0.72 (0.67–0.77) | |||

| χ | 2.99 | |||

| DF | 7 | |||

| P | 0.886 | |||

DF indicates degree of freedom; IEQ, islet equivalents.

In our unadjusted univariate analysis, the following factors were associated with an increased likelihood of postoperative narcotic use: pancreas divisum, any previous ERCP involving stent placement, a high number of previous stents (>3), an earlier sphincterotomy, and preoperative narcotic use of 5 years duration or more. In contrast, the following factors were associated with a decreased likelihood of postoperative narcotic use: hereditary causes of CP and a previous pancreaticojejunostomy or distal pancreatectomy.

After multivariate adjustment using a logistic model, a previous pancreaticojejunostomy was independently associated with a decreased likelihood of postoperative narcotic use [odds ratio (OR), 0.19]; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.05 to 0.66; P = 0.009). In contrast, the following factors were associated with an increased likelihood of postoperative narcotic use: previous stent placement (OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 0.99 to 3.77; P = 0.055), an earlier sphincterotomy (OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.09 to 2.83; P = 0.020), and a high number (>3) of previous stents (OR, 2.73; 95% CI, 1.10 to 6.79; P = 0.031). Our final multivariate model provided good discrimination (AUC = 0.72) and acceptable calibration (P = 0.886).

Predictors of Persistent Pain

For our clinical outcome analysis of the association between potential risk factors and persistent postoperative pancreatic pain similar to preoperative levels, we assessed 452 adult TP-IAT patients who completed at least 1 year of follow-up (Table 4). Information on persistent pain at 1 year was missing for 16 patients. Of those 452 patients, 34 (7.5%) had persistent pain at 1 year.

TABLE 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios Risk Factors Associated With Pancreatitis Pain at 1 Year After TP-IAT

| Unadjusted

|

Multivariate Adjusted

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Cumulative Incidence of pain | 8% | |||

| Age group, years | ||||

| 18–29 | 1.00 | |||

| 30–39 | 1.59 (0.77–3.28) | 0.204 | ||

| 40–49 | 0.97 (0.45–2.07) | 0.929 | ||

| 50–72 | 0.97 (0.39–2.41) | 0.938 | ||

| Female sex | 1.00 (0.44–2.27) | 0.997 | ||

| Pretransplant diabetes | NA | |||

| Causes of chronic pancreatitis | ||||

| Alcoholism | 0.87 (0.25–2.96) | 0.819 | ||

| Idiopathic | 0.81 (0.40–1.65) | 0.556 | ||

| Pancreas divisum | 2.16 (1.03–4.56) | 0.037 | 2.50 (1.10–5.66) | 0.028 |

| Other | 1.00 | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.59 (0.20–1.73) | 0.332 | 0.81 (0.25–2.61) | 0.728 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 1.13 (0.38–3.38) | 0.823 | 1.35 (0.41–4.47) | 0.628 |

| Obese (≥30) | 2.17 (0.99–4.78) | 0.049 | 2.13 (0.88–5.13) | 0.092 |

| Previous surgery | ||||

| Puestow | 0.71 (0.16–30.7) | 0.641 | ||

| Beger or frey | 2.50 (0.28–22.01) | 0.393 | ||

| Whipple | 2.30 (0.74–705) | 0.138 | 3.36 (1.00–11.34) | 0.051 |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 1.13 (0.25–5.00) | 0.877 | ||

| Previous stent | 1.81 (0.82–3.98) | 0.134 | ||

| Number of previous stents | ||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 0.77 (0.36–1.65) | 0.498 | 0.91 (0.34–2.47) | 0.853 |

| 2 | 0.61 (0.14–2.63) | 0.501 | 0.92 (0.19–4.58) | 0.922 |

| ≥3 | 3.24 (1.54–6.79) | 0.001 | 3.44 (1.33–8.90) | 0.023 |

| Any spincterotomy | 1.25 (0.60–2.60) | 0.551 | ||

| Years with pancreatitis | ||||

| <5 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥5 | 1.60 (0.79–3.25) | 0.193 | ||

| Years of narcotic use | ||||

| <5 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥5 | 2.07 (0.92–4.65) | 0.032 | ||

|

| ||||

| Areas under the curve Hosmer-Lemeshow | 0.75 (0.67–0.83) | |||

| χ | 5.64 | |||

| DF | 8 | |||

| P | 0.687 | |||

DF indicates degree of freedom; IEQ, islet equivalents; NA, not applicable.

Relief from pancreatic pain—the primary indication for a TP-IAT—was reported in 92.6% of our patients. In our unadjusted univariate analysis, the following factors were associated with an increased likelihood of persistent pain: pancreas divisum, body mass index >30, a previous Whipple resection, a high number (>3) of previous stents, and preoperative narcotic use of 5 years or more.

In our adjusted analysis, the following factors were independently associated with an increased likelihood of persistent pain: pancreas divisum, previous Whipple resection, body mass index >30, and a high number (>3) of previous stents.

Predictors of Islet Graft Failure

For our clinical outcome analysis of the association between potential risk factors and islet graft failure, we assessed 378 adult patients who completed at least 1 year of follow-up (Table 5). Information on islet graft failure at 1 year was incomplete or missing for 112 adults. Forty-seven (12.5%) patients had islet graft failure at 1 year. The following factors were independently associated with an increased likelihood of islet graft failure: lower islet yield, alcohol use as a cause of CP, and duration of pancreatitis >5 years. The strongest independent risk factor for islet graft failure was a low islet yield; moreover, we noted a strong dose-response relationship between the lowest-yield category (<2000 IEQ) and the highest (≥5000): islet graft failure was 25-fold more likely in the lowest-yield category.

TABLE 5.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios Risk Factors Associated With Islet Graft Failure at 1 Year After TP-IAT

| Unadjusted

|

Multivariate Adjusted

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Cumulative incidence of islet graft failure | 17% | |||

| Age group, years | ||||

| 18–29 | 1.00 | |||

| 30–39 | 1.43 (0.79–2.62) | 0.238 | ||

| 40–49 | 1.00 (0.54–1.83) | 0.988 | ||

| 50–72 | 0.77 (0.36–1.67) | 0.514 | ||

| Female sex | 0.61 (0.33–1.12) | 0.110 | ||

| Pretransplant diabetes | 4.21 (1.75–10.13) | 0.001 | ||

| Causes of chronic pancreatitis | ||||

| Alcoholism | 3.52 (1.60–7.73) | 0.001 | 3.25 (1.09–9.72) | 0.035 |

| Idiopathic | 0.41 (0.23–0.73) | 0.002 | ||

| Pancreas divisum | 0.50 (0.23–1.11) | 0.083 | ||

| Genetic or hereditary | 3.11 (1.57–6.19) | <0.001 | ||

| Other | 1.00 | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 1.11 (0.52–2.36) | 0.796 | ||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 1.00 | |||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 1.25 (0.49–3.22) | 0.643 | ||

| Obese (≥30) | 1.08 (0.51–2.29) | 0.847 | ||

| IEQ per kg body weight | ||||

| <2000 | 14.88 (6.93–31.95) | <0.001 | 28.41 (6.24–129) | <0.001 |

| 2000–2999 | 0.63 (0.24–1.71) | 0.366 | 4.11 (0.71–21.67) | 0.103 |

| 3000–3999 | 0.53 (0.20–1.42) | 0.201 | 2.92 (0.53–16.01) | 0.218 |

| 4000–4999 | 0.14 (0.02–1.05) | 0.026 | 1.01 (0.09–11.68) | 0.992 |

| ≥5000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Previous surgery | ||||

| Puestow | 5.44 (2.06–14.38) | 0.002 | ||

| Beger or frey | NA | |||

| Whipple | 0.41 (0.09–1.81) | 0.226 | ||

| Distal pancreatectomy | 8.66 (2.72–27.53) | <0.001 | ||

| Previous stent | 0.75 (0.41–1.36) | 0.344 | ||

| Number of previous stents | ||||

| None | 1.00 | |||

| 1 | 1.20 (0.68–2.11) | 0.538 | ||

| 2 | 0.67 (0.25–1.80) | 0.427 | ||

| ≥3 | 0.64 (0.30–1.36) | 0.242 | ||

| Any spincterotomy | 0.66 (0.36–1.24) | 0.195 | ||

| Years with pancreatitis | ||||

| <5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥5 | 2.08 (1.16–3.71) | 0.013 | 2.17 (0.94–4.98) | 0.069 |

| Years of narcotic use | ||||

| <5 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥5 | 2.34 (1.20–4.57) | 0.011 | ||

|

| ||||

| Areas under the curve Hosmer-Lemeshow | 0.86 (0.80, 0.92) | |||

| χ | 2.66 | |||

| DF | 7 | |||

| P | 0.915 | |||

CI indicates confidence interval; DF, degree of freedom; IEQ, islet equivalents; NA, not applicable.

Predictors of Impaired HRQoL

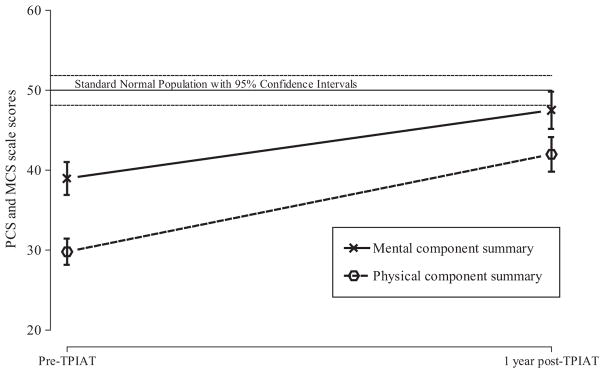

Information on HRQoL data both pre-TP-IAT and post-TP-IAT was available for 83 adult patients. For the 83 adults in this subgroup analysis, HRQoL improved postoperatively, according to their PCS and MCS scores on the SF-36 before surgery versus at 1 year (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 1). The strongest predictor of improvement in HRQoL was health status before surgery.

FIGURE 1.

Mean PCS and MCS scales score and 95% confidence limits for 112 patients—pre-TPIAT and at 1-year post-TPIAT. Reference standard normal population and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

In our multivariate adjusted model for physical health status based on a PCS score before surgery of ≥50, we found that a lower score before surgery (ie, <30) increased the likelihood of impaired physical health at 1 year. The odds of reporting impaired physical health at 1 year were 9 times higher for patients on narcotics than for those not on narcotics. We found a similar but statistically nonsignificant association between impaired physical health before surgery and persistent postoperative pancreatic pain (Tables 6 and 7).

TABLE 6.

Multivariate Adjusted Impaired Physical Health (PCS <50) at 1 Year After TP-IAT

| Cumulative Incidence of Impaired Physical Health | 64%

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Adjusted

| ||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Before surgery | ||

| PCS score >30 | 1.00 | |

| PCS score ≤30 | 6.66 (2.06–21.50) | 0.002 |

| No narcotic use at 1 year | 1.00 | |

| Narcotic use at 1 year | 7.55 (2.19–26.03) | 0.001 |

| No pain at 1 year | 1.00 | |

| Pain at 1 year | 4.47 (0.73–27.54) | 0.107 |

| Islet function | ||

| Graft failure | 1.31 (0.10–17.94) | 0.838 |

| Partial function | 1.00 | |

| Full function | 0.94 (0.25–3.44) | 0.920 |

|

| ||

| Area under the curve Hosmer-Lemeshow | 0.85 (0.77–0.93) | |

| χ | 5.61 | |

| DF | 7 | |

| P | 0.586 | |

DF indicates degree of freedom; PCS, physical component summary.

TABLE 7.

Multivariate Adjusted Impaired Emotional Health (MCS <50) at 1 Year After TP-IAT

| Cumulative Incidence of Impaired Emotional Health | 41%

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Adjusted

| ||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Before surgery | ||

| MCS score >30 | 1.00 | |

| MCS score ≤30 | 2.78 (0.83–9.34) | 0.099 |

| No narcotic use at 1 year | 1.00 | |

| Narcotic use at 1 year | 6.15 (2.06–18.32) | 0.001 |

| No pain at 1 year | 1.00 | |

| Pain at 1 year | 3.84 (0.95–15.47) | 0.058 |

| Islet function | ||

| Graft failure | 1.27 (0.10–16.30) | 0.670 |

| Partial function | 1.00 | |

| Full function | 1.28 (0.42–3.92) | 0.853 |

| Area under the curve Hosmer-Lemeshow | 0.80 (0.71–0.90) | |

| χ | 4.17 | |

| DF | 5 | |

| P | 0.525 | |

DF indicates degree of freedom; MCS, mental component summary.

Impaired physical health before surgery (PCS score <30) was independently associated with islet graft failure. The likelihood of impaired physical health at 1 year was 39% higher in patients with islet graft failure (OR, 1.31) than in those with full islet function (OR, 0.94).

Impaired emotional health before surgery was independently associated with impaired emotional health at 1 year. A lower MCS score before surgery (ie, <30) increased the likelihood of impaired emotional health at 1 year.

In addition, narcotic use and persistent pain at 1 year independently increased the odds of impaired emotional health. But even though islet graft failure was related to impaired physical health, it was unrelated to impaired emotional health (Figs. 2–5).

FIGURE 2.

Patient survival rates.

FIGURE 5.

Physical and mental health.

DISCUSSION

For patients with severe CP that is refractory to medical or endoscopic interventions, a TP-IAT offers the potential for pain relief, cessation of narcotic dependence, and improved HRQoL.10,22–26 However, we have a limited understanding of why this surgery succeeds in many patients, but fails to reduce pain in others.

Our study that covered a multiyear period (February 14, 1977, through November 3, 2014) and included a large number of patients (490 adults and 91 children) confirmed that satisfactory outcomes can be achieved after a TP-IAT, with very minimal surgical and all cause mortality. In most of our patients, the primary aims of pain relief and improved quality of life were fulfilled. At 1 year, only 7.5% of patients had persistent pancreatic pain similar to preoperative levels, and only 30% patients were using any narcotics. Yet that 7.5% incidence of persistent pain remains concerning.

Pain in CP is the result of a complex physiologic interaction between peripheral nociception (from inflammation, tissue damage, and pancreatic neuropathic changes) and the modulation of peripheral nociceptive input (by both peripheral and central nervous system pain signaling).27–30 Moving past earlier conceptualizations of chronic pain as simply acute pain that has lasted for over 3 months, investigators now appreciate that peripheral nociceptive signals have the ability to change the sensitivity of both peripheral and central nervous system neurons; these changes do not easily reverse with surgery. In fact, in a study involving quantitative sensory testing (QST), the Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group found that patients with poor outcomes after drainage or partial resection procedures had hyperalgesia (ie, central sensitization) before surgery.31 This central and peripheral sensitization represents one of the neuroplastic changes that occur in the nervous system in response to pain—changes that must be addressed, to the extent possible, after surgery.

In our study, patients were more likely to have persistent pain if they had undergone placement of a high number (>3) of stents, if they had used narcotics for >5 years preoperatively, or if they had pancreas divisum. Characterized as sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, pancreas divisum is often treated with repeat ERCP; thus, pancreas divisum itself may or may not be the cause of the pain syndrome. Instead, some patients may have developed completely iatrogenic CP due to repetitive stenting.32,33 In such patients, the original cause of pain might have been unrelated to the pancreas and thus would not be cured by a TP-IAT.

The impact of repetitive cycles of severe acute pain must not be understated or ignored when discussing its implication for long-term outcomes in patients with CP. In particular, our data suggest that multiple sphincterotomies, repetitive stenting, or previous surgical procedures have the potential to produce central sensitization. These factors must be considered when treating patients with CP, especially when deciding to intervene with a TP-IAT. Years of repetitive stenting alone, just as a temporizing measure, could have already increased the risk of suboptimal outcomes after a TP-IAT.

Because intractable pain is a major detriment to quality of life, sensitization must be adequately addressed after a TP-IAT. Unfortunately, few guidelines exist for this group of patients, particularly for pain management. Narcotic therapy is a mainstay of pain management after a TP-IAT, yet the literature on CP suggests that adjuvant therapy with pregabalin or gabapentin, that is, with γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) agonists, can directly target the central sensitization component.34

Ultimately, these neuroplastic changes can also lead to complex behavior responses that contribute to persistent pain, such as muscle memory and guarding responses. Other contributors to abdominal pain mimicking the pain of CP include gastrointestinal dysmotility, narcotic bowel syndrome, chronic postsurgical pain, and other causes that may be difficult to diagnose or treat.35,36 In our study, we were unable to analyze mental health diagnoses directly from our dataset, but we postulate that patients with comorbid mental illnesses, including substance abuse disorders, are at risk for persistent pain. To address the above issues and maximize recovery after a TP-IAT, our center has instituted, as of 3 years ago, aggressive preoperative preparation and pain control, meticulous multimodal perioperative pain management, ongoing psychological support, and structured postoperative rehabilitation.

Several groups have reported that HRQoL for patients with CP is far below average before a TP-IAT, with significant improvement postoperatively.10–12,37,38 In our study, we specifically analyzed which of our patients remained below the normal range on the SF-36 for the physical and mental component summary scores at 1 year. Patients with the lowest scores before surgery (ie, ≤30) were highly likely to have low scores at 1 year—that is, they were approximately 7 times more likely to have impaired physical health and about 3 times more likely to have impaired mental health.

The clinical implications of this finding are 2-fold. First, when deciding on the optimal timing of a TP-IAT, delaying it until the patient is highly compromised in terms of physical and mental health may be detrimental. The most severely impaired patients are not likely to reach a normal state of health, or at least not by 1 year after surgery. Second, patients with severely impaired mental and physical health before a TP-IAT may require more intensive treatment both pre- and postoperatively, including close psychological and behavioral interventions to manage psychosocial comorbidities.

For our study, we defined islet graft failure by C-peptide levels ≤0.5 ng/mL; when C-peptide levels were unavailable, we instead went by the criterion of multiple daily doses of insulin required to achieve blood sugar control. The International Islet Transplant Registry defines graft failure by C-peptide levels less than 0.3 ng/mL.39 In our definition, we were more conservative, in light of clinical studies indicating that patients with type 1 diabetes saw a benefit in glucose control with C-peptide levels ≥0.6 ng/mL.40

In line with previous observations by our group and by others, we again found in this study that a lower islet mass was the most significant predictor of graft failure. For patients who received <2000 IEQ/kg (versus >5000), the OR of graft failure was 28.41. Prolonged duration of CP (>5 years) and alcohol etiology also independently predicted graft failure. A lower islet mass isolated in patients with alcoholic etiology has been previously reported (1265 vs 2189 IEQ/Kg)41. Previous pancreaticojejunostomy and genetic/hereditary cause of CP also predicted graft failure in our univariate analysis, but those 2 factors lost significance in our multivariate model that included islet mass, likely because they are simply markers or mediators for low islet recovery.

In conclusion, our study found that patients with a prolonged duration (>5 years) of narcotic use and repetitive stenting (>3 previous stents) before their TP-IAT were more likely to have persistent pain or prolonged narcotic use postoperatively. The strongest independent risk factor for islet graft failure was a low islet yield. Our results should be considered as hypothesis-generating and serve as a background for further investigation of the patient subgroups we identified. Such research will require cooperation among all TP-IAT centers, so that we can prospectively collect longitudinal data using common metrics.

FIGURE 3.

Narcotic use.

FIGURE 4.

Insulin independence.

Acknowledgments

The authors express appreciation to Katherine Foster for preparing the manuscript and figures for publication, over and over again. The authors would also like to thank Mary Knatterud, PhD, for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yadav D, Timmons L, Benson JT, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of chronic pancreatitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2192–2199. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States Part III: Liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1134–1144. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179–1187. e1–e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ammann RW. Diagnosis and management of chronic pancreatitis: current knowledge. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136:166–174. doi: 10.4414/smw.2006.11182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steer ML, Waxman I, Freedman S. Chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1482–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmberg JT, Isaksson G, Ihse I. Long-term results of pancreaticojejunostomy in chronic pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;160:339–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Nio Y, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:676–684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasikala M, Talukdar R, Pavan kumar P, et al. beta-Cell dysfunction in chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1764–1772. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najarian JS, Sutherland DE, Matas AJ, et al. Human islet autotransplantation following pancreatectomy. Transplant Proc. 1979;11:336–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutherland DE, Radosevich DM, Bellin MD, et al. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.040. discussion 424–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chinnakotla S, Bellin MD, Schwarzenberg SJ, et al. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation in children for chronic pancreatitis: indication, surgical techniques, postoperative management, and long-term outcomes. Ann Surg. 2014;260:56–64. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinnakotla S, Radosevich DM, Dunn TB, et al. Long-term outcomes of total pancreatectomy and islet auto transplantation for hereditary/genetic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:530–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anazawa T, Balamurugan AN, Bellin M, et al. Human islet isolation for autologous transplantation: comparison of yield and function using SERVA/Nordmark versus Roche enzymes. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2383–2391. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balamurugan AN, Chang Y, Bertera S, et al. Suitability of human juvenile pancreatic islets for clinical use. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1845–1854. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balamurugan AN, Breite AG, Anazawa T, et al. Successful human islet isolation and transplantation indicating the importance of class 1 collagenase and collagen degradation activity assay. Transplantation. 2010;89:954–961. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181d21e9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juang JH, Bonner-Weir S, Wu YJ, et al. Beneficial influence of glycemic control upon the growth and function of transplanted islets. Diabetes. 1994;43:1334–1339. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.11.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellin MD, Freeman ML, Schwarzenberg SJ, et al. Quality of life improves for pediatric patients after total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplant for chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. Boston: New England Medical Center, Health Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The rand 36-item health survey 1.0. Health Economics. 1993;2:217–227. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M, Pryor ER. Logistic Regression: A Self-learning Text. Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow L. Applied Logistic Regression. Vol. 21. Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcea G, Weaver J, Phillips J, et al. Total pancreatectomy with and without islet cell transplantation for chronic pancreatitis: a series of 85 consecutive patients. Pancreas. 2009;38:1–7. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181825c00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad SA, Lowy AM, Wray CJ, et al. Factors associated with insulin and narcotic independence after islet autotransplantation in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:680–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon J, DeLegge M, Morgan KA, et al. Impact of total pancreatectomy with islet cell transplant on chronic pancreatitis management at a disease-based center. Am Surg. 2008;74:735–738. doi: 10.1177/000313480807400812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Witkowski P, Savari O, Matthews JB. Islet autotransplantation and total pancreatectomy. Adv Surg. 2014;48:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez Rilo HL, Ahmad SA, D’Alessio D, et al. Total pancreatectomy and autologous islet cell transplantation as a means to treat severe chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:978–989. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152:S2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demir IE, Tieftrunk E, Maak M, et al. Pain mechanisms in chronic pancreatitis: of a master and his fire. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:151–160. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0731-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moshiree B, Zhou Q, Price DD, et al. Central sensitisation in visceral pain disorders. Gut. 2006;55:905–908. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.078287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gebhart GF. Visceral pain-peripheral sensitisation. Gut. 2000;47(Suppl 4):iv54–iv55. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.suppl_4.iv54. discussion iv58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouwense SA, Ahmed Ali U, ten Broek RP, et al. Altered central pain processing after pancreatic surgery for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1797–1804. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakman YG, Safdar K, Freeman ML. Significant clinical implications of prophylactic pancreatic stent placement in previously normal pancreatic ducts. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1095–1098. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozarek RA. Pancreatic stents can induce ductal changes consistent with chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:93–95. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)70958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouwense SA, Olesen SS, Drewes AM, et al. Effects of pregabalin on central sensitization in patients with chronic pancreatitis in a randomized, controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grunkemeier DM, Cassara JE, Dalton CB, et al. The narcotic bowel syndrome: clinical features, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1126–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.06.013. quiz 1121–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618–1625. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68700-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan KA, Borckardt J, Balliet W, et al. How are select chronic pancreatitis patients selected for total pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation? Are there psychometric predictors? J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:693–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan K, Owczarski SM, Borckardt J, et al. Pain control and quality of life after pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:129–133. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1744-y. discussion 133–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bellin MD, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, et al. Islet autotransplantation to preserve beta cell mass in selected patients with chronic pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus undergoing total pancreatectomy. Pancreas. 2013;42:317–321. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182681182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Effect of intensive therapy on residual beta-cell function in patients with type 1 diabetes in the diabetes control and complications trial. A randomized, controlled trial. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:517–523. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-7-199804010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dunderdale J, McAuliffe JC, McNeal SF, et al. Should pancreatectomy with islet cell autotransplantation in patients with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis be abandoned? J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]