Abstract

Background

Improved outcomes are associated with the Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium, and Early exercise/mobility bundle (ABCDE); however, implementation issues are common. As yet, no study has integrated the barriers to ABCDE to provide an overview of reasons for less successful efforts. The purpose of this review was to identify and catalog the barriers to ABCDE delivery based on a widely used implementation framework, and to provide a resource to guide clinicians in overcoming barriers to implementation.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed, CINAHL, and Scopus for original research articles from January 1, 2007, to August 31, 2016, that identified barriers to ABCDE implementation for adult patients in the ICU. Two reviewers independently reviewed studies, extracted barriers, and conducted thematic content analysis of the barriers, guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Discrepancies were discussed, and consensus was achieved.

Results

Our electronic search yielded 1,908 articles. After applying our inclusion/exclusion criteria, we included 49 studies. We conducted thematic content analysis of the 107 barriers and identified four classes of ABCDE barriers: (1) patient-related (ie, patient instability and safety concerns); (2) clinician-related (ie, lack of knowledge, staff safety concerns); (3) protocol-related (ie, unclear protocol criteria, cumbersome protocols to use); and, not previously identified in past reviews, (4) ICU contextual barriers (ie, interprofessional team care coordination).

Conclusions

We provide the first, to our knowledge, systematic differential diagnosis of barriers to ABCDE delivery, moving beyond the conventional focus on patient-level factors. Our analysis offers a differential diagnosis checklist for clinicians planning ABCDE implementation to improve patient care and outcomes.

Key Words: ICU, mechanical ventilation, quality improvement

Abbreviations: ABCDE, Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium, and Early exercise/mobility bundle; CFIR, Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

The Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium, and Early exercise/mobility bundle (ABCDE) is a complex multicomponent bundle of evidence-based practices associated with shorter duration of mechanical ventilation and improved physical function for mechanically ventilated adults.1, 2 Individual components of the bundle are effective in minimizing adverse outcomes for mechanically ventilated patients.3 Data also indicate that bundling the intervention components is associated with an even greater reduction in delirium and ICU length of stay.2, 4, 5, 6 However, despite evidence of the effectiveness of the ABCDE, it is not implemented widely or consistently as recommended.7

Many studies have examined the effectiveness of each individual component of the bundle and implementation challenges of delivering ABCDE. A handful of prior systematic reviews examined barriers to the implementation of the individual bundle components. For example, Hashem et al8 recently published an overview of early mobility that focused on some of the patient-level barriers to the early mobility (E) part of ABCDE, identifying sedation and specific patient tubes and lines as important barriers to mobilization in the ICU. Another review assessed implementation strategies specific to ICU delirium (D), identifying the most common implementation strategies but focusing on only this single bundle component.9 As yet, no systematic review has summarized the barriers to ABCDE delivery as a bundle.

The absence of a synthesis of the barriers to ABCDE delivery hinders two important efforts. First, it provides little guidance for those just initiating an ABCDE effort as to what barriers they should assess in their own institution. Second, we lack a comprehensive differential diagnosis that adequately catalogs important barriers and provides a resource to assist in overcoming them. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to identify the barriers to ABCDE implementation published in the peer-reviewed literature for adult patients in the ICU.

We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)10 as a guide when mapping the identified barriers to ABCDE implementation. The CFIR is a widely used implementation framework, and provides a structured approach to examining barriers to implementation. The five domains of the CFIR include the following: (1) characteristics of the intervention (refers to the actual intervention being implemented); (2) inner setting (refers to the social, economic, political, and social environment through which the implementation process proceeds and that will influence implementation); (3) outer setting (refers to the economic, social, or political context of the organization); (4) characteristics of individuals (refers to the people who play an important role in implementation); and (5) process (refers to the active changes that occur to encourage or discourage implementation of the intervention). The five CFIR domains are further subdivided into constructs that provide additional clarification to each of the domains. For example, constructs in the outer setting domain include patient needs and resources, defined as “the extent to which the patient needs as well as barriers and facilitators to meet those needs are accurately known and integral to the organization.”10 For the inner setting, constructs include culture, structural characteristics, implementation climate, and readiness for implementation—which all refer to the environment in which the intervention is being implemented. We catalogued the barriers described as contributing to lack of ABCDE implementation, organized within the CFIR domains.

Materials and Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist was used to guide this review.11 PubMed, CINAHL, and Scopus were searched to find articles on barriers to implementing the ABCDE in the ICU. We did not search the grey literature (ie, conference proceedings, material on Websites, abstracts, policy reports) in this review. Searches were conducted for literature published from January 1, 2007, through August 31, 2016. To create a comprehensive search, no language or publication type limits were applied at the search strategy level. The MEDLINE search strategy was conducted in PubMed by combining selected medical subject headings and key words. The key word searches were limited to the title and abstract fields to increase specificity. Our search strategy combined the location of our population (intensive care and ICUs) with aspects of ABCDE (spontaneous awakening trials, spontaneous breathing trials, delirium prevention and control, early ambulation, critical illness/rehabilitation, and early mobilization) and barriers of ABCDE implementation. A unique search strategy was created for each database to ensure appropriate utilization of key words and relevant controlled vocabulary terms (ie, Medical Subject Heading terms in PubMed/MEDLINE, CINAHL Headings in CINAHL). One example of a full search strategy is included in e-Appendix 1.

This review was divided into three stages: title and abstract review, full-text article review, and data extraction. Each title and abstract was assessed by two team members (D. K. C. and M. R. W.) for relevancy, and was rejected if it did not meet one of the following inclusion criteria: (1) focused on providers caring for adult patients in the ICU, (2) assessed ABCDE implementation, (3) empirical qualitative or quantitative studies, and (4) identified barriers to ABCDE implementation. After title/abstract review, two reviewers (D. K. C. and M. R. W.) independently reviewed full texts for relevancy and excluded articles if they met one of the following exclusion criteria: (1) nonempirical literature (case studies, editorials, or opinion pieces), (2) study protocol articles or systematic reviews, (3) pediatric or neonatal patient population, (4) articles related to sepsis or ventilator-associated pneumonia bundle implementation, (5) no elicitation of barriers/facilitators to ABCDE implementation, (6) no evaluation of ABCDE implementation (ie, only examined patient outcomes, not implementation outcomes), (7) not focused on adult patients in the ICU, (8) prevalence or pathophysiology studies, and (9) non-hospital-based studies. We focused our review on empirical research that identified barriers to implementation of ABCDE. Case reports were excluded from our review because they usually describe single site or limited examples, which are not often generalizable. Intervention studies are also rarely reported as case reports. If there was uncertainty about a title/abstract’s relevance, it was included in the full-text article review. A third reviewer (M. M. or A. E. S.) resolved any discrepancies or disagreements between the two initial reviewers (D. K. C. and M. R. W.).

Once all full-text articles had been reviewed and any disagreements reconciled, two reviewers (D. K. C. and M. R. W.) independently extracted the reported barriers from the included articles for synthesis. We did not limit inclusion based on study design and therefore collected qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies of barriers to ABCDE implementation. Identified barriers were extracted from the tables/figures in the full text and the discussion section of each article, as applicable. We also recorded the study design (mixed methods/quantitative/qualitative) and whether the study examined the entire ABCDE bundle or one of the individual bundle components. After data extraction, two authors (D. K. C. and M. R. W.) verified data extraction, study design, and bundle elements from each study. Any disagreements or discrepancies were discussed and consensus achieved before proceeding.

Once the list of extracted barriers was assembled, two reviewers (D. K. C. and M. R. W.) independently coded the barriers, categorizing and coding similar barriers together. The goal of this initial coding was to reduce the number of barriers because many extracted barriers were the same (eg, team communication and interprofessional team communication). The identified barriers and results of the thematic content analysis serve as the summary measures in this systematic review. We used the CFIR as a guide for coding the barriers through thematic content analysis.12 Four authors (D. K. C., M. R. W., M. M., and A. E. S.) categorized and coded the barriers identified within the CFIR domains: (1) characteristics of intervention, (2) inner setting, (3) outer setting, (4) characteristics of individuals, and (5) process. All coding was verified between the reviewers and all authors. Consensus was achieved among all coauthors, and any discrepancies were discussed before the coding scheme was finalized. Using the identified barriers within each CFIR domain and the domain definitions and the constructs within each domain, we identified a common theme among those listed barriers, domains, and constructs. We purposely renamed domains to better reflect the coded barriers and to be more meaningful to clinicians.

Results

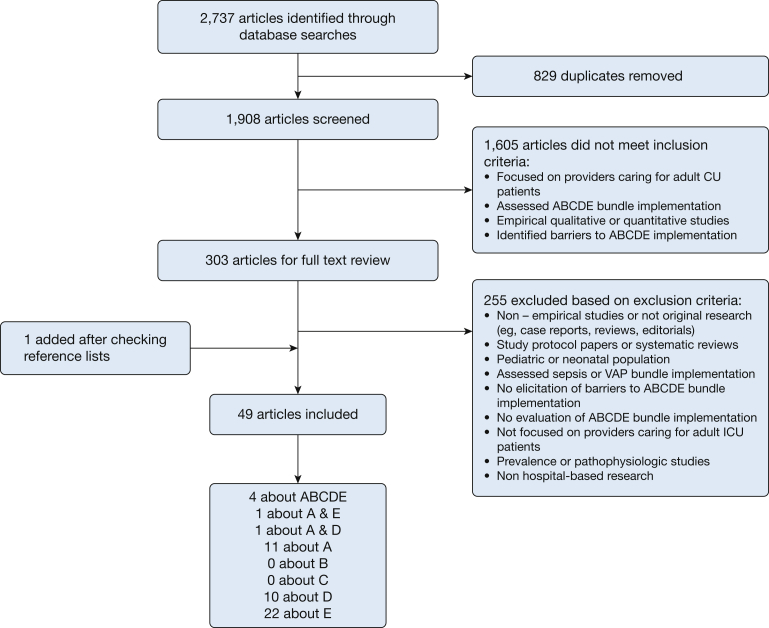

Our inclusion/exclusion criteria and flowchart are displayed in Figure 1. We identified 1,908 unique citations for review after de-duplication of the search results. After reviewing all titles and abstracts, 1,605 titles were excluded by the application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, leaving 303 articles. There were 255 articles excluded after full-text review. We retrieved one article after hand-checking the reference list of the included articles. The final number of included articles was 49.1, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search results and inclusion/exclusion criteria. A = awakening; ABCDE = Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium, and Early exercise/mobility; B = spontaneous breathing trials; C = coordination; D = delirium; E = early mobility; VAP = ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Of the 49 articles, four focused on implementation of the entire ABCDE1, 18, 21, 51; one examined awakening and early mobility49; one examined awakening and delirium28; 11 examined implementation of awakening19, 30, 35, 42, 43, 44, 47, 52, 54, 55, 56; 10 examined implementation of delirium monitoring24, 25, 27, 36, 38, 48, 50, 53, 57, 58; and 22 assessed early mobility implementation (Fig 1).13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 22, 23, 26, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 37, 39, 40, 41, 45, 46, 59, 60 No studies were identified that focused exclusively on either spontaneous breathing trials (B) or coordination (C) implementation. All studies focused on adult patients in the ICU; however, the patient population and ICU type varied across studies. Most studies used quantitative study designs (n = 23), 16 used mixed-methods approaches, and 10 were qualitative studies (e-Table 1).

After data extraction, we identified 107 barriers to ABCDE delivery (e-Table 2), which were then further summarized into four classes of barriers according to the CFIR domains (Table 1). No barriers were identified that were coded as the fifth CFIR domain, process. Patient-related barriers to ABCDE delivery (CFIR outer setting) were primarily patient instability or safety concerns and lack of patient cooperation. Clinician-related barriers (CFIR characteristics of individuals) refer to issues such as lack of knowledge about the protocol, clinician preference for autonomy, and staff safety concerns. Protocol-related barriers (CFIR intervention characteristics) were inherent problems with the protocol or bundle for implementation, and concerns with testing and clarity of the protocol by clinicians. ICU contextual barriers (CFIR inner setting) refer to the environment in which care is provided and, namely, culture, interprofessional team issues (eg, lack of support, staffing), physical equipment, and resources. A schematic of the summarized barriers is displayed in e-Figure 1.

Table 1.

Identified Barriers to ABCDE Delivery From the Literature

| 1. Patient-related barriers (CFIR outer setting) |

| • Lack of patient cooperation |

| • Patient instability and patient safety concerns (hemodynamics, treatment-related adverse events, physiologic patient issues) |

| • Patient status issues (ie, diarrhea, fatigue, leaking wound, patient weight or size, confusion/agitation, imminent death) |

| 2. Clinician-related barriers (CFIR characteristics of individuals) |

| • Lack of knowledge and awareness about protocol |

| • Lack of conceptual agreement with guidelines |

| • Lack of self-efficacy and confidence in implementing protocol |

| • Clinician preference for autonomy (resistance to change, expectation of nurse) |

| • Staff and patient safety concerns |

| • Perception that rest equals healing |

| • Reluctance to follow protocol (previous execution associated with negative outcomes) |

| • Lack of confidence that protocol will improve workflow or improve patient outcomes |

| • Perceived workload (hard work) |

| • Staff attitude and lack of buy-in |

| • Safety of tubes, catheters, and wires |

| 3. Protocol-related barriers (CFIR intervention characteristics) |

| • Unavailable or cumbersome to use protocols |

| • Unclear protocol criteria and agreement or discomfort with guidelines |

| • Protocol development cost (time and money to develop) |

| • Learning curve (possibility for clinician to test guideline and observe other clinicians using the guideline easily) |

| • Lack of clarity as to who is responsible, steps needed to take, and expected standards for protocol implementation |

| • Lack of confidence in evidence supporting protocol and guideline developer |

| • Lack of confidence in reliability of screening tools |

| 4. ICU contextual barriers (CFIR inner setting) |

| • Culture (safety culture) |

| • Interprofessional team care coordination, communication, and collaboration barriers |

| • Lack of leadership/management |

| • Interprofessional clinician staffing, workload, and time |

| • Lack of interprofessional team support and training/expertise |

| • Physical environment, equipment, and resources |

| • Staff turnover |

| • Low prioritization and perceived importance |

| • Competing priorities and need for further planning |

| • Scheduling conflicts (ie, patient off unit, at dialysis, procedure) |

ABCDE = Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium, and Early exercise/mobility bundle; CFIR = Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Discussion

Our analysis suggests that the main barriers to ABCDE implementation fall within four distinct domains, consistent with the CFIR domains, which we renamed as (1) patient-related; (2) clinician-related; (3) protocol-related; and, not previously identified in past reviews, (4) ICU contextual barriers.10 Implementation interventions aimed at improving ABCDE implementation must address individual clinician- and patient-related barriers and emphasize the intervention-specific and contextual issues surrounding implementation of a multicomponent clinical intervention, such as ABCDE in the ICU.

We provide the first, to our knowledge, systematic differential diagnosis of barriers to implementation of the ABCDE, moving beyond the conventional focus on patient-level factors. Our data may help guide ICU clinicians when beginning ABCDE implementation. Although all identified barriers will not be present in every ICU, we identify a range of barriers present. The wide range of barriers identified underscores the complexity of ABCDE delivery but also the need for careful selection of implementation strategies to support more effective implementation. To do so, ICUs should first assess their own unit’s barriers to be able to design implementation interventions that are responsive to the barriers within their own particular context.61 Using the barriers within domains we identified as a differential diagnostic checklist, ICUs can assess their units’ barriers and develop ways to overcome the most important barriers they find.62 This approach is frequently used in implementation research, and uses a wide variety of frameworks, strategies, and behavior change techniques to achieve effective implementation.63, 64

One example of how an ICU could potentially use the identified barriers in this review as a differential diagnosis checklist for their specific unit and context would be to first assess some of the ICU contextual barriers—interprofessional staffing and coordination. A unit could evaluate the interprofessional staffing patterns and the ability of the team to coordinate. For example, are physical therapists available for mobility? Can physical therapists coordinate with nurses to conduct early mobility? Does an opportunity exist for the interprofessional team to discuss the process65 in delivering ABCDE in the unit? Another set of barriers that could be assessed are protocol-related issues. Before designing an implementation strategy, the ICU interprofessional team could, for example, first clarify and finalize the specific ABCDE protocol for their unit, with input from multiple different clinician types, and even patients and/or families.66 Doing so can help minimize concerns with the protocol, belief in its effectiveness, or integration into workflow, which were some of the protocol-related barriers we identified. These are just two examples of ways that ICU clinicians could use the identified barriers in our review as a differential diagnosis checklist and begin to assess their own unit’s specific barriers to ABCDE implementation. The next step, after assessing their unit’s barriers, would be to design specific implementation interventions tailored to overcome their unit’s barriers, taking into consideration their context, interprofessional team, and capacity for implementation.67 This would entail identifying and prioritizing the barriers in their own context, and then developing a tailored implementation plan to overcome the high priority barriers for their setting. Indeed, a recent Cochrane review68 on factors influencing clinician use of evidence-based guidelines to facilitate ventilator weaning identified that the social and cultural context and environment is critical to effective implementation.

Of note, most studies in this review assessed early mobility implementation (n = 22). Although early mobility is an important part of the bundle, to continue efforts to improve implementation, particularly for complex multicomponent clinical interventions such as ABCDE, more attention is needed to understand the barriers to other components of the bundle, such as spontaneous breathing trials and coordination of spontaneous breathing and spontaneous awakening trials. These particular components of the bundle may be more complex in the dynamic ICU environment, and therefore require further examination.

Although this is the first study to systematically summarize barriers to ABCDE delivery, there are noted limitations of this work. We note in particular the absence of any reports that identified potential barriers within the fifth CFIR domain, process; our methodology does not let us distinguish between possible reasons for this. It may be that the process domain rarely causes problems for implementation of ABCDE, but it could also be that previous investigations simply have not looked in that area or did not report on implementation process factors. Many of the studies included in the review did not use systematic frameworks for implementation, which may have limited the ability to elicit barriers related to process, potentially accounting for the absence of identified process barriers. We focused exclusively on studies that reported and evaluated implementation of either one or all components of the ABCDE bundle, but we did exclude the grey literature (eg, conference proceedings, abstracts), which may have eliminated some studies. However, we do present the most up-to-date search possible. The studies included in this review assessed ABCDE implementation for adult patients in the ICU, but there was variation in patient population and ICU type across studies, which may limit generalizability.

We did not rank or prioritize the identified barriers because the goal of this review was to summarize the existing literature. We acknowledge that lack of ranking and prioritization of the barriers is a noted limitation of our work. However, many barriers to implementation are often context-specific. A priori imposing our own prioritization schema on these data would be neglecting the important and influential contribution of ICU contextual factors. We encourage future work to attempt to prioritize barriers across similar settings. We used the CFIR as a guide for coding the summarized barriers, which is one of many different implementation frameworks available.69 Because of the nature of the research question and our inclusion of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies, any reported barrier is a subjective assessment of perceived difficulties implementing ABCDE; this limits our ability to assess risk of bias within and across the individual studies. Similarly, the summary measures cannot be reported as risk ratios or difference in means as done in meta-analyses11 but is a more qualitative thematic coding of the barriers according to the CFIR domains and constructs.

Conclusions

Implementation of the ABCDE in the ICU is complex, and clinicians and administrators face many challenges when striving to provide high-quality care to patients in the ICU. Using the identified barriers catalogued into relevant domains—individual patient- and clinician-related barriers, protocol-related barriers, and ICU context—ICU clinicians can use these domains as a potential differential diagnosis checklist, to assess their unit’s specific barriers prior to ABCDE implementation. The next step would involve developing an implementation plan that takes into consideration implementation strategies tailored to their specific ICU context and barriers, to improve implementation of the ABCDE and, ultimately, improve patient care and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: D. K. C. takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including data and analysis. D. K. C. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis. M. R. W., E. G., M. M., S. G., T. J. I., and A. E. S. contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data or decision to submit for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This work does not necessarily represent the views of the US Government or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figure, and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Dr Deena Costa and the work described in this manuscript are supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) K08 Award [K08HS024552; PI Costa]; and the Veterans Health Administration’s Office of Analytics and Business Intelligence. D. K. C. also receives in-kind research support from the Michigan Health and Hospital Association Keystone Center.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Balas M.C., Burke W.J., Gannon D. Implementing the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle into everyday care: opportunities, challenges, and lessons learned for implementing the ICU Pain, Agitation, and Delirium Guidelines. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9 suppl 1):S116–S127. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a17064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balas M.C., Vasilevskis E.E., Olsen K.M. Effectiveness and safety of the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1024–1036. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ely E.W., Baker A.M., Dunagan D.P. Effect on the duration of mechanical ventilation of identifying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(25):1864–1869. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612193352502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girard T.D., Kress J.P., Fuchs B.D. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):126–134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan B., Fadel W.F., Tricker J.L. Effectiveness of implementing a wake up and breathe program on sedation and delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(12):e791–e795. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klompas M., Anderson D., Trick W. The preventability of ventilator-associated events. The CDC Prevention Epicenters Wake Up and Breathe Collaborative. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(3):292–301. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1394OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller M.A., Govindan S., Watson S.R., Hyzy R.C., Iwashyna T.J. ABCDE, but in that order? A cross-sectional survey of Michigan ICU sedation, delirium and early mobility practices. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(7):1066–1071. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-066OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashem M.D., Parker A.M., Needham D.M. Early mobilization and rehabilitation of the critically ill patient. Chest. 2016;150(3):722–731. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trogrlić Z., Jagt M van der, Bakker J. A systematic review of implementation strategies for assessment, prevention, and management of ICU delirium and their effect on clinical outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19:157. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damschroder L.J., Aron D.C., Keith R.E., Kirsh S.R., Alexander J.A., Lowery J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;89(9):873–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guest G., MacQueen K.M., Namey E.E. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appleton R.T., Mackinnon M., Booth M.G., Wells J., Quasim T. Rehabilitation within Scottish intensive care units: a national survey. J Intensive Care Soc. 2011;12(3):221–227. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakhru R.N., Wiebe D.J., McWilliams D.J., Spuhler V.J., Schweickert W.D. An environmental scan for early mobilization practices in U.S. ICUs. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(11):2360–2369. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakhru R.N., McWilliams D.J., Wiebe D.J. ICU structure variation and implications for early mobilization practices: an international survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(9):1527–1537. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201601-078OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barber E.A., Everard T., Holland A.E., Tipping C., Bradley S.J., Hodgson C.L. Barriers and facilitators to early mobilisation in intensive care: a qualitative study. Aust Crit Care. 2015;28(4):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassett R.D., Vollman K.M., Brandwene L., Murray T. Integrating a multidisciplinary mobility programme into intensive care practice (IMMPTP): a multicentre collaborative. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2012;28(2):88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassen R., Adams K.M., Danesh V. Rethinking critical care: decreasing sedation, increasing delirium monitoring, and increasing patient mobility. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015;41(2):62–74. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(15)41010-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck L., Johnson C. Implementation of a nurse-driven sedation protocol in the ICU. Dynamics. 2008;19(4):25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berney S., Haines K., Skinner E.H., Denehy L. Safety and feasibility of an exercise prescription approach to rehabilitation across the continuum of care for survivors of critical illness. Phys Ther. 2012;92(12):1524–1535. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20110406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrothers K.M., Barr J., Spurlock B., Ridgely M.S., Damberg C.L., Ely E.W. Contextual issues influencing implementation and outcomes associated with an integrated approach to managing pain, agitation, and delirium in adult ICUs. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9 suppl 1):S128–S135. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a2c2b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro E., Turcinovic M., Platz J., Law I. Early mobilization: changing the mindset. Crit Care Nurse. 2015;35(4):e1–e6. doi: 10.4037/ccn2015512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dafoe S., Chapman M.J., Edwards S., Stiller K. Overcoming barriers to mobilisation of patients in an intensive care unit. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2015;43(6):719–727. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1504300609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devlin J.W., Fong J.J., Howard E.P. Assessment of delirium in the intensive care unit: nursing practices and perceptions. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17(6):555–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eastwood M.G., Peck L., Bellomo R., Baldwin I., Reade C.M. A questionnaire survey of critical care nurses’ attitudes to delirium assessment before and after introduction of the CAM-ICU. Aust Crit Care. 2012;25(3):162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engel H.J., Needham D.M., Morris P.E., Gropper M.A. ICU early mobilization: from recommendation to implementation at three medical centers. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9 suppl 1):S69–S80. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a240d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flagg B., Cox L., McDowell S., Mwose J.M., Buelow J.M. Nursing identification of delirium. Clin Nurse Spec. 2010;24(5):260–266. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181ee5f95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster J., Kelly M. A pilot study to test the feasibility of a nonpharmacologic intervention for the prevention of delirium in the medical intensive care unit. Clin Nurse Spec. 2013;27(5):231–238. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3182a0b9f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garzon-Serrano J., Ryan C., Waak K. Early mobilization in critically ill patients: patients’ mobilization level depends on health care provider’s profession. PM R. 2011;3(4):307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill K.V., Voils S.A., Chenault G.A., Brophy G.M. Perceived versus actual sedation practices in adult intensive care unit patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(10):1331–1339. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris C.L., Shahid S. Physical therapy-driven quality improvement to promote early mobility in the intensive care unit. Proc (Baylor Univ Center) 2014;27(3):203–207. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2014.11929108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrold M.E., Salisbury L.G., Webb S.A., Allison G.T. Early mobilisation in intensive care units in Australia and Scotland: a prospective, observational cohort study examining mobilisation practises and barriers. Crit Care. 2015;19:336. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1033-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holdsworth C., Haines K.J., Francis J.J., Marshall A., O’Connor D., Skinner E.H. Mobilization of ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: an elicitation study using the theory of planned behavior. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1243–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jolley S.E., Regan-Baggs J., Dickson R.P., Hough C.L. Medical intensive care unit clinician attitudes and perceived barriers towards early mobilization of critically ill patients: a cross-sectional survey study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014;14:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-14-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joseph-Belfort A. A brief report of student research: protocol versus nursing practice: sedation vacation in a surgical intensive care unit. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2009;28:81-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Jung J.H., Lim J.H., Kim E.J. The experience of delirium care and clinical feasibility of the CAM-ICU in a Korean ICU. Clin Nurs Res. 2013;22(1):95–111. doi: 10.1177/1054773812447187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knott A., Stevenson M., Harlow S.K. Benchmarking rehabilitation practice in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Soc. 2015;16(1):24–30. doi: 10.1177/1751143714553901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Law T.J., Leistikow N.A., Hoofring L., Krumm S.K., Neufeld K.J., Needham D.M. A survey of nurses’ perceptions of the intensive care delirium screening checklist. Dynamics. 2012;23(4):18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leditschke I.A., Green M., Irvine J., Bissett B., Mitchell I.A. What are the barriers to mobilizing intensive care patients? Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2012;23(1):26–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malone D., Ridgeway K., Nordon-Craft A., Moss P., Schenkman M., Moss M. Physical therapist practice in the intensive care unit: results of a national survey. Phys Ther. 2015;95(10):1335–1344. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20140417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendez-Tellez P.A., Dinglas V.D., Colantuoni E. Factors associated with timing of initiation of physical therapy in patients with acute lung injury. J Crit Care. 2013;28(6):980–984. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller M.A., Krein S.L., George C.T., Watson S.R., Hyzy R.C., Iwashyna T.J. Diverse attitudes to and understandings of spontaneous awakening trials: results from a statewide quality improvement collaborative*. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(8):1976–1982. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a40ba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller M.A., Krein S.L., Saint S., Kahn J.M., Iwashyna T.J. Organisational characteristics associated with the use of daily interruption of sedation in US hospitals: a national study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(2):145–151. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller M.A., Bosk E.A., Iwashyna T.J., Krein S.L. Implementation challenges in the intensive care unit: the why, who, and how of daily interruption of sedation. J Crit Care. 2012;27(2):218.e1–218.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Needham D.M., Korupolu R. Rehabilitation quality improvement in an intensive care unit setting: implementation of a quality improvement model. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2010;17(4):271–281. doi: 10.1310/tsr1704-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nydahl P., Ruhl A.P., Bartoszek G. Early mobilization of mechanically ventilated patients: a 1-day point-prevalence study in Germany. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1178–1186. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Connor M., Bucknall T., Manias E. Sedation management in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units: doctors’ and nurses’ practices and opinions. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(3):285–295. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Özsaban A., Acaroglu R. Delirium assessment in intensive care units: practices and perceptions of Turkish nurses. Nurs Crit Care. 2016;21(5):271–278. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pohlman M.C., Schweickert W.D., Pohlman A.S. Feasibility of physical and occupational therapy beginning from initiation of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(11):2089–2094. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f270c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riekerk B., Pen E.J., Hofhuis J.G., Rommes J.H., Schultz M.J., Spronk P.E. Limitations and practicalities of CAM-ICU implementation, a delirium scoring system, in a Dutch intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2009;25(5):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reimers M., Miller C. Clinical nurse specialist as change agent: delirium prevention and assessment project. Clin Nurse Spec. 2014;28(4):224–230. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts R.J., de Wit M., Epstein S.K., Didomenico D., Devlin J.W. Predictors for daily interruption of sedation therapy by nurses: a prospective, multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2010;25(4):660.e1–660.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scott P., McIlveney F., Mallice M. Implementation of a validated delirium assessment tool in critically ill adults. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2013;29(2):96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sneyers B., Laterre P.F., Perreault M.M., Wouters D., Spinewine A. Current practices and barriers impairing physicians’ and nurses’ adherence to analgo-sedation recommendations in the intensive care unit - a national survey. Crit Care. 2014;18:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0655-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sneyers B., Laterre P.F., Bricq E., Perreault M.M., Wouters D., Spinewine A. What stops us from following sedation recommendations in intensive care units? A multicentric qualitative study. J Crit Care. 2014;29(2):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanios M.A., de Wit M., Epstein S.K., Devlin J.W. Perceived barriers to the use of sedation protocols and daily sedation interruption: a multidisciplinary survey. J Crit Care. 2009;24(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trogrlić Z., Ista E., Ponssen H.H. Attitudes, knowledge and practices concerning delirium: a survey among intensive care unit professionals. Nurs Crit Care. 2017;22(3):133–140. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van den Boogaard M., Pickkers P., van der Hoeven H., Roodbol G., van Achterberg T., Schoonhoven L. Implementation of a delirium assessment tool in the ICU can influence haloperidol use. Crit Care. 2009;13(4):R131. doi: 10.1186/cc7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Winkelman C., Peereboom K. Staff-perceived barriers and facilitators. Crit Care Nurse. 2010;30(2):S13–S16. doi: 10.4037/ccn2010393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zanni J.M., Korupolu R., Fan E. Rehabilitation therapy and outcomes in acute respiratory failure: an observational pilot project. J Crit Care. 2010;25(2):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Skolarus T., Sales A. Implementation issues: towards a systematic and stepwise approach. In: Richards D., Hallberg I., editors. Complex Interventions in Health: An Overview of Research Methods. Routledge; London, UK: 2015. pp. 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flottorp S.A., Oxman A.D., Krause J. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baker R., Camosso-Stefinovic J., Gillies C. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD005470. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005470.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wensing M., Wollersheim H., Grol R. Organizational interventions to implement improvements in patient care: a structured review of reviews. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Costa D., Dammeyer J., White M. Interprofessional team interactions about complex care in the ICU: pilot development of an observational rating tool. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:408. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2213-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carman K., Dardess P., Maurer M.E. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Braithwaite J., Marks D., Taylor N. Harnessing implementation science to improve care quality and patient safety: a systematic review of targeted literature. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(3):321–329. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jordan J., Rose L., Dainty K.N., Noyes J., Blackwood B. Factors that impact on the use of mechanical ventilation weaning protocols in critically ill adults and children: a qualitative evidence-synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD011812. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011812.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tabak R.G., Khoong E.C., Chambers D.A., Brownson R.C. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.