Abstract

INTRODUCTION

To provide a cross-walk between the recently proposed short MoCA (s-MoCA) and MMSE within a clinical cohort.

METHOD

791 participants, with and without neurological conditions, received both the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) at the same visit. s-MoCA scores were calculated and equipercentile equating was used to create a cross-walk between the s-MoCA and MMSE

RESULTS

As expected, s-MoCA scores were highly correlated (Pearson r=0.82, p<0.001) with MMSE scores. s-MoCA scores correctly classified 85% of healthy older adults and 91% of individuals with neurological conditions that impair cognition. In addition, we provide an easy to use table that enables the conversion of s-MoCA score to MMSE scores.

DISCUSSION

The s-MoCA is quick to administer, provides high sensitivity and specificity for cognitive impairment, and now can be compared directly to the MMSE.

Keywords: s-MoCA, MMSE, cognitive screening, test equating, brief cognitive test

INTRODUCTION

The need for adequate and effective cognitive screening is essential given the rapid growth of the elderly population and the increasing prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related disorders. Unfortunately, those with, or developing, dementia often go undiagnosed and many are not even evaluated [1]. In fact, upwards of 40 percent of older adults with cognitive impairment are often not identified as impaired [2]. The failure to assess cognitive abilities likely hampers the diagnosis and treatment of neurodegenerative and non-neurodegenerative dementia, and may significantly affect patients’ and family members’ wellbeing. Yet, most current memory and cognitive screening measures remain too lengthy for regular use in community and primary care settings. Consequently, despite widespread attention given to the growing economic costs of treating and caring for people with AD and other neurodegenerative diseases [3], the availability of time and cost-effective cognitive screening tests are limited. In order to serve this demand, well-validated and efficient cognitive screening tests are needed for administration as part of routine clinical visits and check-ups[4].

Many cognitive screening measures exist; the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [5] and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [6] are two of the most common. Recent work[7] confirms and extends prior findings on the diagnostic utility of the MMSE and MoCA. While the MMSE has a long history of use in clinical and research settings for the assessment and monitoring of acute neurocognitive impairments, it has limited utility in detecting subtle changes in cognition that may signal pending impairment in at-risk individuals [8, 9]. In addition, the MMSE has large ceiling effects [10]—even when corrected for education [11], and relatively poor accuracy in the identification of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild AD [12]. The MoCA overcomes some, but not all, of the limitations of the MMSE, and evidence is accumulating that the MoCA may eventually supplant the MMSE as the gold-standard in cognitive screening for AD dementia [7, 13]. Specifically, the MoCA includes more robust measures of visuospatial and executive function [6], which likely reduces ceiling and practice effects, but enhances the potential for floor effects. Indeed, comparisons of these two measures find that the MoCA has better sensitivity and specificity in AD, Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) [7] and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [13]. Thus, the MoCA may be most informative when attempting to differentiate mild forms of dementia from typical age-related decline. However, one of the most significant limitations of the MoCA is the 10–15 minute administration time.

Recently, using a scale-shortening method first described in [14], we established and validated a short form of the standard MoCA (s-MoCA) composed of 8 items, which takes approximately 5 minutes to administer [15]. Item response theory and computerized adaptive testing simulation were used to derive the s-MoCA in 1,850 well-characterized community-dwelling individuals with and without neurodegenerative disease. The s-MoCA was highly correlated with the original MoCA, exhibited robust diagnostic classification, and cross-validation procedures substantiated the selected items. Thus, the s-MoCA is highly comparable to the standard MoCA, generalizable to healthy individuals and those with neurological conditions and, most importantly, can be administered more quickly.

Yet, we acknowledge that adoption of the s-MoCA within the primary care setting, neurology clinics and specialized research settings may be difficult given the historical importance and ubiquity of the MMSE in clinimetrics, research programs and randomized clinical trials. Thus, in the current report we provide a straightforward method for converting s-MoCA scores to MMSE scores. The results will facilitate the adoption of the s-MoCA within the clinic by providing continuity in cognitive assessment scores in the clinic and comparability of data in the research setting that will ensure valid longitudinal assessment.

METHODS

Participants

All participants (n=791) were recruited from the Penn Memory Center and Clinical Core of the University of Pennsylvania’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center. One-hundred thirty-eight healthy older adults (HOA) and 653 individuals with a neurological condition were assessed. AD (n=340) and MCI (n=109) diagnoses accounted for the majority of individuals. To increase generalizability of equated scores, participants with the following neurological conditions were also included: frontotemporal dementia (n=15), corticobasal syndrome (n=5), dementia with Lewy Bodies (n=25), dementia, unspecified (n=19), hydrocephalus (n=26), multiple clinical diagnoses (n=16), indeterminate neurological condition (n=56), PD (n=2), Posterior Cortical Atrophy (n=4), Primary Progressive Aphasia (7), progressive supranuclear palsy (n=2), psychiatric illness (n=13), traumatic Brain Injury (n=2), and vascular dementia (n=12). Note that individuals with multiple clinical diagnoses were individuals with at least two neurological or psychiatric clinical diagnoses. Clinical assessments included history, physical, and neurological examinations conducted by experienced clinicians, including the review of neuroimaging, psychometric and laboratory data. A consensus diagnosis was established using standardized clinical criteria for AD, MCI, or other neurological or psychiatric conditions presenting with cognitive impairment [16–18]. Additional details on subject recruitment and evaluation have been previously published [7, 15]

All 791 participants were administered the MMSE and MoCA during the same visit. The MMSE result was available during consensus diagnosis, but the MoCA was not. Informed consent for the use of all data was obtained from all persons, in accord with The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

s-MoCA scores

Combining sophisticated approaches of item response theory and computerized adaptive testing analytics in 1,850 individuals, we previously established an approach for generating s-MoCA scores [15]. This short form consists of 8-items from the original MoCA, including the following items: 1) clock draw, 2) serial subtraction, 3) orientation (place), 4) recall, 5) abstraction (watch), 6) naming (rhino), 7) trail-making, and 8) language fluency (See [15] Supplemental Material). The score ranges from 0–16, is comparable to the standard MoCA and outperforms another short version of the MoCA, which was derived from an AD/MCI sample only[19]. Correct responses on these 8 items are summed to generate the total s-MoCA score.

Statistical Analysis

Between-group comparisons of MMSE and s-MoCA scores were performed using independent sample t-tests. s-MoCA scores were equated to MMSE scores using the equipercentile equating method [7, 20], which has been used to equate numerous standardized tests [13, 15, 21]. This statistical method allows for the determination of comparable test scores from two different measures on the basis of their corresponding percentile ranks. The advantage of the equipercentile equating method is that the equated scores always fall within the range of possible scores. Log-linear smoothing was applied to avoid an irregular distribution of scores [22]. Polychoric correlations between items were used to estimate internal consistency of the s-MoCA. Equipercentile equating with log-linear smoothing was performed using the ‘equate’ library in the R statistical package (v3.2.2. “Fire Safety”).

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics and test performance are displayed in Table 1A. Individual performance on the s-MoCA encompassed all possible scores from 0 to 16. s-MoCA and MMSE scores were highly correlated (Pearson r=0.82, p<.001). On average, HOA scored significantly higher on both the MMSE = 29.34 (0.92) and s-MoCA = 13.53 (1.93) relative to individuals with any type of neurological disorder—MMSE = 21.77 (6.27) and s-MoCA = 6.23 (3.81), and higher than individuals with MCI—MMSE = 26.09 (3.34) and s-MoCA = 8.64(2.85) or AD — MMSE =19.53 (5.81) and s-MoCA = 4.79 (3.22). For comparison, standard MoCA scores are presented in Table 1A and Supplemental Figure 3. Those with neurological conditions (Age = 74.36 (8.88) were slightly, but significantly older than healthy older adults (Age = 70.29 (8.98); t(790)=−4.71, p=1.26×10−6). Internal consistency of the items of the s-MoCA was high, Cronbach’s alpha =0.90 and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Sum of Boxes scores were inversely associated with s-MoCA scores (Pearson r(677)=−0.74, p<2.20×10−16). Sensitivity, specificity, Youden Index, positive and negative predictive value, clinical cut-off score and classification accuracy are presented in Table 1B. As expected, the s-MoCA had high sensitivity and specificity and performed similarly to the full MoCA—while typically outperforming the MMSE-- at identifying individuals with cognitive dysfunction. s-MoCA scores correctly classified 90% of individuals when differentiating individuals with neurological conditions from HOA, which was 2% better than performance of the standard MoCA and 7% better than the MMSE.

Table 1A.

Participant demographics and cognitive screening performance.

| N | Age M (SD) years | Gender F/M | % Caucasian | Education M(SD) years | Total CDR | MMSE Score (range 0–30) | MoCA Score (range 0–30) | s-MoCA score (range 0–16) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Neurological Diagnoses | 653 | 74.37 (8.89) | 381/272 | 74% | 13.95 (4.26) | 4.22 (3.36) | 22 (6) | 16 (7) | 6 (4) |

| AD | 340 | 75.89 (8.24) | 220/120 | 71% | 13.39 (4.27) | 5.38 (3.27) | 20 (6) | 14 (6) | 5 (3) |

| MCI | 109 | 72.95 (8.64) | 57/52 | 78% | 14.71 (3.96) | 1.68 (1.26) | 26 (3) | 21 (4) | 9 (3) |

| HC | 138 | 70.28 (8.99) | 92/46 | 79% | 16.95 (2.74) | 0.06 (0.22) | 29 (1) | 27 (2) | 14 (2) |

s-MoCA = Short MoCA; CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (Sum of Boxes)

All significant pairwise comparisons p<0.01.

Age: HC<All Neuro, AD, MCI; AD>MCI;

Sex: HC ≠ All Neuro; HC=AD; AD≠MCI; MCI≠HC;

Race: HC=All Neuro, AD, MCI

Education: HC>All Neuro, AD, & MCI; MCI>AD

MMSE: HC>All Neuro, MCI, AD; MCI>AD

MoCA: HC>All Neuro, AD, MCI; MCI>AD

Short MoCA: HC>All Neuro, AD, MCI; MCI>AD;

Table 1B.

Diagnostic parameters for the MoCA and Short MoCA in the Full Sample, AD, MCI, PD, and PDD.

| Full Sample vs. HC | AD vs. HC | MCI vs. HC | AD vs. MCI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoCA | AUC (+− 95% CIa) | 0.97 (0.95–0.98) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) |

| Sensitivity/Specificity | 0.86/0.96 | 0.94/1.00 | 0.94/0.80 | 0.76/0.78 | |

| Youden Index | 0.82 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.54 | |

| Cutoff Score | 23 | 22 | 25 | 24 | |

| PPV/NPV | 0.99/0.59 | 1.00/0.88 | 0.78/0.94 | 0.92/0.51 | |

| Classification Accuracy | 88% | 96% | 86% | 77% | |

| Short MoCA (s-MoCA) | AUC (+− 95% CI) | 0.95 (0.94–0.97)* | 0.99 (0.98–0.99)* | 0.93 (0.90–0.96)* | 0.81 (0.76–0.85)*^ |

| Sensitivity/Specificity | 0.91/0.85 | 0.96/0.91 | 0.87/0.85 | 0.67/0.79 | |

| Youden Index | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.46 | |

| Cutoff Score | 11 | 10 | 11 | 6 | |

| PPV/NPV | 0.97/0.68 | 0.96/0.91 | 0.87/0.85 | 0.91/0.44 | |

| Classification Accuracy | 90% | 95% | 86% | 70%*^ | |

| MMSE | AUC (+− 95% CI) | 0.94 (0.92–0.96)* | 0.98 (0.98–0.99)* | 0.88 (0.84–0.92)*# | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) |

| Sensitivity/Specificity | 0.81/0.96 | 0.94/0.96 | 0.75/0.85 | 0.79/0.79 | |

| Youden Index | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.58 | |

| Cutoff Score | 27 | 27 | 28 | 18 | |

| PPV/NPV | 0.99/0.52 | 0.98/0.88 | 0.80/0.81 | 0.92/0.55 | |

| Classification Accuracy | 83%# | 95% | 81%# | 79% |

Significantly lower than the Standard MoCA in permutation testing of AUC using roc.test function in R package pROC (p<0.05).

Significantly lower than the Short MoCA in permutation testing of AUC using roc.test function in R package pROC (p<0.05).

Significantly lower than the MMSE in permutation testing of AUC using roc.test function in R package pROC (p<0.05).

Confidence Intervals estimated using DeLong method and n=2000 bootstraps

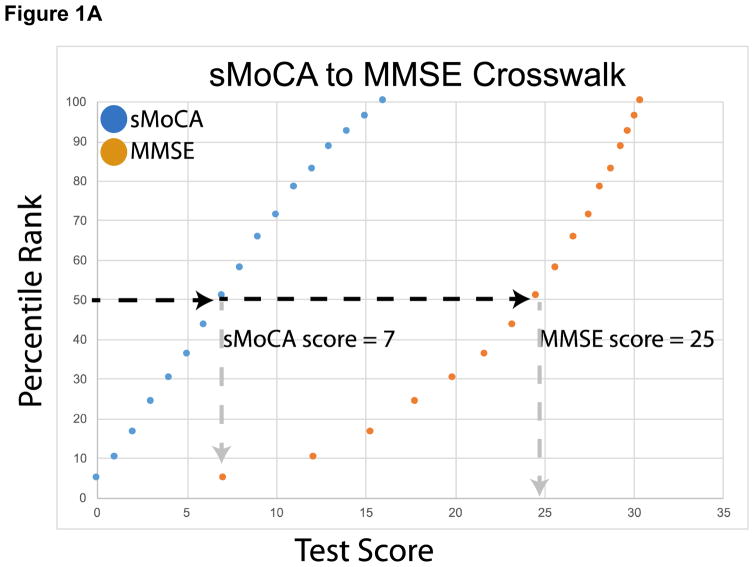

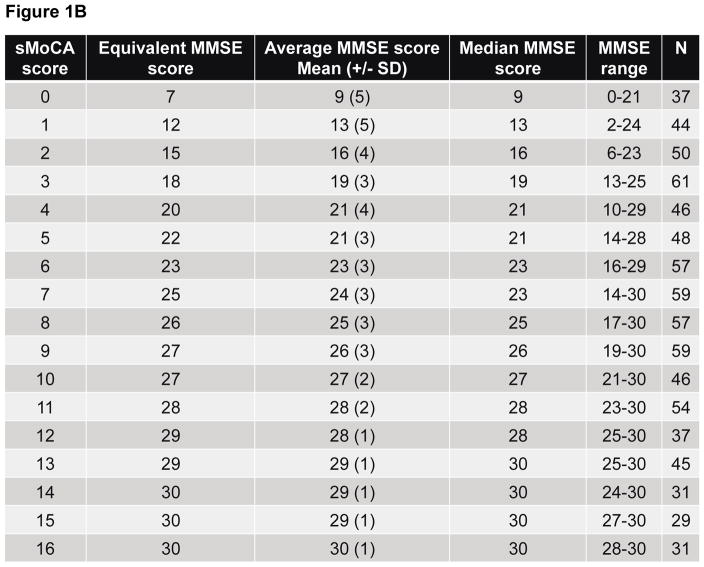

A plot of the equipercentile equivalent scores on the MMSE and s-MoCA is presented in Figure 1A. For example, an s-MoCA score=7 is equivalent to an MMSE score=25, as both of these scores fall at the 50th percentile within a sample with a wide range of cognitive impairment, including healthy individuals. Figure 1B provides the mean, median and range for MMSE scores for each score on the s-MoCA, and their respective equipercentile equivalent score on the MMSE. Equated scores for only AD dementia, including MCI are presented in Supplemental Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 1.

Figure 1.

Equipercentile equating of the sMoCA and MMSE> Corresponding test scores and percentile ranks allow for conversion of sMoCA scores to MMSE scores. For example, a sMoCA score of 7 (50th percentile) is equivalent to a MMSE score of 25 (50th percentile). All neurological conditions were included in the cross-walk.

Figure 1A. A plot of the equipercentile equivalent scores on the MMSE and s-MoCA. As an example, a score of 7 on the s-MoCA is equivalent to a score of 25 on the MMSE, as both of these scores fall at the 50th percentile within a sample with a wide range of cognitive impairment, including healthy individuals.

Figure 1B. Equivalent, average, median and the range of MMSE scores are shown for each possible score on the s-MoCA. Equivalent MMSE scores were generated using equipercentile equating method. The number of individuals that achieved a given s-MoCA score is shown in the final column.

DISCUSSION

Early and accurate detection of cognitive impairment in older adults that indicates transition to AD dementia can enhance clinical management as well as lead to better understanding of individual differences in disease progression. Thus, there is a need for time- and cost-effective approaches that allow for the identification of prodromal disease stages, particularly in primary care clinics. As early detection becomes more necessary, well-validated and brief measures of cognitive performance, such as the s-MoCA, can provide clinicians an efficient tool with which to routinely screen patients and efficiently identify those in need of specialized care or more comprehensive neuropsychological assessment. Here, we show that in general the s-MoCA outperforms that MMSE in identifying older individuals with mild cognitive dysfunction, provide additional evidence of the clinical utility of the s-MoCA and present a cross-walk between s-MoCA and MMSE scores. This cross-walk will enable the widely recognized cut-off scores on the MMSE to be reliably linked with scores on the s-MoCA.

We believe that the s-MoCA is an ideal screening tool for physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants in primary care practice, as these practitioners are often the first to hear a patient’s complaints. We are encouraged that the s-MoCA works as well as the full MoCA and in many instances better than the MMSE, in particular at differentiating MCI from normal healthy aging. In this respect the s-MoCA can provide a much-needed quick screen in the primary care setting. The s-MoCA can be quite useful in this setting since the assessment of cognitive functioning is a required element of the Medicare Annual Wellness visit [23]. Other early screening questionnaires or tests that are available and recommended by the National Institute of Aging including the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG), the Mini-Cog and the Memory Impairment Screen (MIS)[23]. However, the s-MoCA expands upon these by covering more cognitive domains, and thus may have broader appeal and utility. We add the s-MoCA to the clinician’s toolbox for consideration as a quick and reliable cognitive screen that meets many of the attributes considered necessary for routine use in primary care settings and that can now be directly compared to MMSE performance.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Systematic review: The need for adequate, effective and efficient cognitive screening is essential given the rapid growth of the elderly population and the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive disorders. Unfortunately, dementia screening in the community setting is often overlooked since cognitive assessments are time consuming; this hampers dementia diagnosis and treatment.

Interpretation: The short form MoCA (s-MoCA) outperforms the MMSE, indicating more time efficient cognitive screening inventories can be implemented in clinical and research settings.

Future directions: We hope that prospective studies of dementia will implement the s-MoCA, as this shorten version provides an efficient, valid estimate of cognitive function. We are eager to see the s-MoCA implemented in primary care settings as these practitioners are often the first to hear patient’s complaints, and we believe it can aid in the assessment of cognitive functioning—a required element of the Medicare Annual Wellness visit.

Acknowledgments

The authors express appreciation to the research participants and staff of the Penn Memory Center/Clinical Core of the University of Pennsylvania Alzheimer’s Disease Center, the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Center at the University of Pennsylvania, the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Center (PADRECC) at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center and general neurology clinic at the University of Pennsylvania. The authors would also like to thank Alexis M. Galantino for her assistance in administering the s-MOCA to establish time of testing.

Study Funding:

This work was supported by NIA AG10124, NIMH K01 MH102609 (Dr. Roalf), the Marian S. Ware Alzheimer’s Program/National Philanthropic Trust, and the Institute of Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center Pilot Funding Program (Dr. Roalf). University of Pennsylvania Center of Excellence for Research on Neurodegenerative Diseases (CERND). Penn Udall Center grant: NINDS P50-NS-053488

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Roalf: No disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Dr. Moore: No disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Dr. Mechanic-Hamilton: No disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Dr. Wolk: No disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Dr. Arnold: No disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Dr. Weintraub: No disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Dr. Moberg: No disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Author contributions:

David R. Roalf: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, study supervision. Dr. Roalf takes the role of Principal Investigator, has access to all of the data and takes responsibility for the data, accuracy of data analysis and conduct of the research. Dr. Roalf acknowledges and shares equal contribution as first author with Dr. Moore. Dr. Roalf will serve as the Corresponding Author.

Tyler M. Moore: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, statistical analysis.

Dawn Mechanic-Hamilton: revising the manuscript, study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, study supervision,

David Wolk: study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, study supervision, obtaining funding.

Steven Arnold: study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, study supervision, obtaining funding.

Daniel Weintraub: study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, study supervision, obtaining funding.

Paul J. Moberg: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, study supervision.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kotagal V, Langa KM, Plassman BL, Fisher GG, Giordani BJ, Wallace RB, et al. Factors associated with cognitive evaluations in the United States. Neurology. 2015;84:64–71. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chodosh J, Petitti DB, Elliott M, Hays RD, Crooks VC, Reuben DB, et al. Physician recognition of cognitive impairment: evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1051–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wimo A, Winblad B, Jönsson L. An estimate of the total worldwide societal costs of dementia in 2005. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2007;3:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brayne C, Fox C, Boustani M. Dementia screening in primary care: Is it time? JAMA. 2007;298:2409–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roalf DR, Moberg PJ, Xie SX, Wolk DA, Moelter ST, Arnold SE. Comparative accuracies of two common screening instruments for classification of Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy aging. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2013;9:529–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravaglia G, Forti P, Maioli F, Servadei L, Martelli M, Brunetti N, et al. Screening for mild cognitive impairment in elderly ambulatory patients with cognitive complaints. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:374–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03324625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slavin MJ, Sandstrom CK, Tran TT, Doraiswamy PM, Petrella JR. Hippocampal volume and the Mini-Mental State Examination in the diagnosis of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1404–10. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zadikoff C, Fox SH, Tang-Wai DF, Thomsen T, de Bie R, Wadia P, et al. A comparison of the mini mental state exam to the Montreal cognitive assessment in identifying cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:297–9. doi: 10.1002/mds.21837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franco-Marina F, García-González J, Wagner-Echeagaray F, Gallo J, Ugalde O, Sánchez-García S, et al. The Mini-mental State Examination revisited: ceiling and floor effects after score adjustment for educational level in an aging Mexican population. International psychogeriatrics/IPA. 2010;22:72–81. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoops S, Nazem S, Siderowf A, Duda J, Xie S, Stern M, et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;73:1738–45. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34b47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Steenoven I, Aarsland D, Hurtig H, Chen-Plotkin A, Duda JE, Rick J, et al. Conversion between Mini-Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and Dementia Rating Scale-2 scores in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1809–15. doi: 10.1002/mds.26062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore TM, Scott JC, Reise SP, Port AM, Jackson CT, Ruparel K, et al. Development of an Abbreviated Form of the Penn Line Orientation Test Using Large Samples and Computerized Adaptive Test Simulation. 2015 doi: 10.1037/pas0000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roalf DR, Moore TM, Wolk DA, Arnold SE, Mechanic-Hamilton D, Rick J, et al. Defining and validating a short form Montreal Cognitive Assessment (s-MoCA) for use in neurodegenerative disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312723. jnnp-2015-312723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris JC, Edland S, Clark C, Galasko D, Koss E, Mohs R, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Part IV. Rates of cognitive change in the longitudinal assessment of probable Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1993;43:2457. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.12.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statitical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text revision (DSM-IV-TR) ed. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horton DK, Hynan LS, Lacritz LH, Rossetti HC, Weiner MF, Cullum CM. An Abbreviated Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for Dementia Screening. The Clinical neuropsychologist. 2015;29:1–13. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2015.1043349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolen MJ, Brennan RL. Test equating: Methods and practices. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fong TG, Fearing MA, Jones RN, Shi P, Marcantonio ER, Rudolph JL, et al. Telephone interview for cognitive status: Creating a crosswalk with the Mini-Mental State Examination. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2009;5:492–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moses T, vonDavier AA. An SAS macro for loglinear smoothing: applications and implications. Montreal: American Educational Research Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordell CB, Borson S, Boustani M, Chodosh J, Reuben D, Verghese J, et al. Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit in a primary care setting. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2013;9:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.